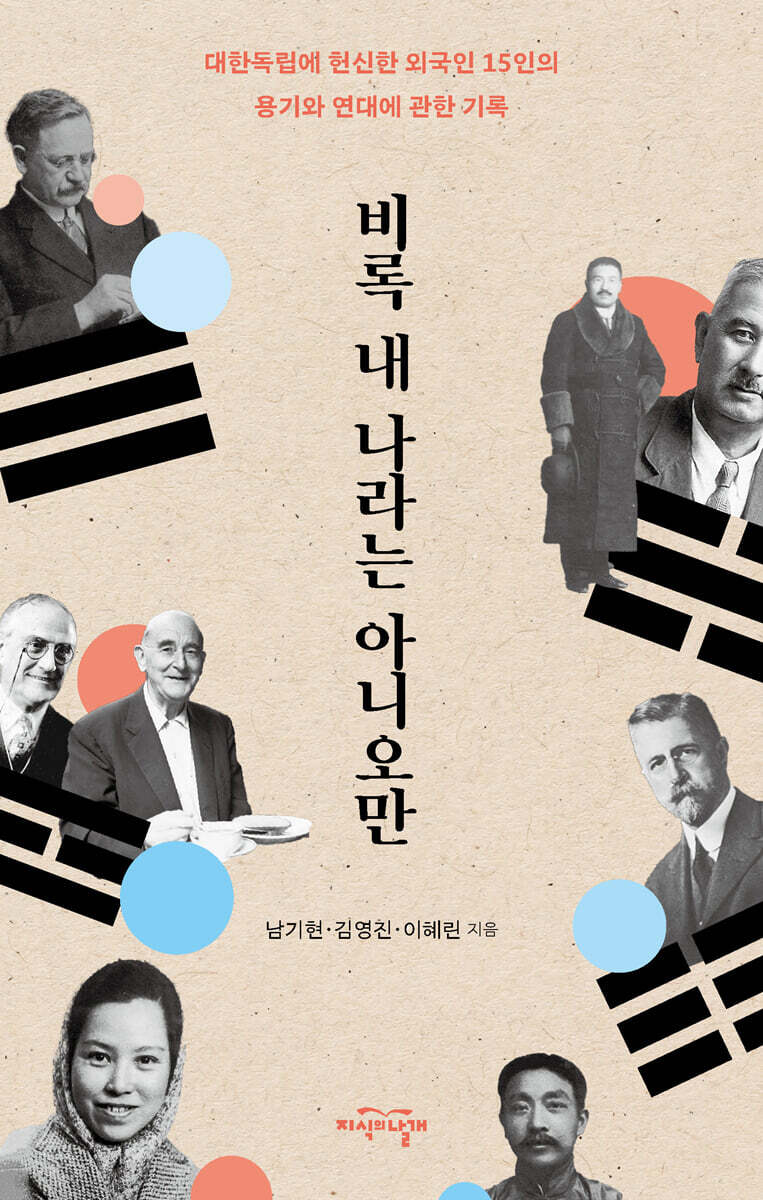

Even though it's not my country

|

Description

Book Introduction

The daily humiliation and violence of colonial Korea

Foreigners who resisted together

Their lives and beliefs became known only after the 80th anniversary of liberation.

The daily violence and humiliation perpetrated in colonial lands! Sometimes nonviolently, sometimes strategically, Koreans resisted the oppression of Japanese imperialism.

After enduring 30 years of gloomy struggles, we finally achieved independence, and this year marks the 80th anniversary of liberation.

Until now, we have only focused on some independence activists who appear in textbooks.

But did you know that there were foreign independence activists who dedicated themselves to Korea's independence?

"Although Not My Country" follows the lives of 15 foreign independence activists we know little about, and delves into why Joseon's independence was such an important task for them.

This book goes beyond simply highlighting individual dedication.

This book examines the history of the independence movement in three parts, connecting the major events that occurred in colonial Korea and their activities.

From the efforts to restore sovereignty of the Korean Empire (1876–1910), to the courage to defend colonial Korea (1902–1935), and to the righteous solidarity movement against imperialism (1907–1945), it vividly portrays how foreigners participated in and supported Korea's independence over time.

Foreigners who resisted together

Their lives and beliefs became known only after the 80th anniversary of liberation.

The daily violence and humiliation perpetrated in colonial lands! Sometimes nonviolently, sometimes strategically, Koreans resisted the oppression of Japanese imperialism.

After enduring 30 years of gloomy struggles, we finally achieved independence, and this year marks the 80th anniversary of liberation.

Until now, we have only focused on some independence activists who appear in textbooks.

But did you know that there were foreign independence activists who dedicated themselves to Korea's independence?

"Although Not My Country" follows the lives of 15 foreign independence activists we know little about, and delves into why Joseon's independence was such an important task for them.

This book goes beyond simply highlighting individual dedication.

This book examines the history of the independence movement in three parts, connecting the major events that occurred in colonial Korea and their activities.

From the efforts to restore sovereignty of the Korean Empire (1876–1910), to the courage to defend colonial Korea (1902–1935), and to the righteous solidarity movement against imperialism (1907–1945), it vividly portrays how foreigners participated in and supported Korea's independence over time.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

preface

Part 1.

Commitment to restoring sovereignty

Oliver R.

Avison (Abyssin 魚丕信)

1.

A doctor who created a medical education system to lay the foundation for Joseon's independence.

Case File: Righteous Army Uprising

Robert D.

Story

2.

A journalist who exposed the violation of diplomatic sovereignty and informed the world.

Case file 'Eulsa Treaty'

Frederick A.

Mackenzie

3. Journalists who testified to the violation of sovereignty through “The Tragedy of the Korean Empire”

Case File: Righteous Army War

Homer B.

Hulbert (Hulbert Law)

4.

The "voluntary diplomats" who rushed to The Hague to reclaim diplomatic sovereignty.

Case File: Special Envoy of the International Peace Conference

Part 2.

Courage to protect Joseon

Frank W.

Schofield (Seok Ho-pil)

5.

A veterinarian who protected Joseon by documenting the Japanese military's oppression through photographs.

Case File: Je-Am-Ri Massacre

Huang Zhu

6.

A publisher with a solid network across Korea, China, and Japan

Case File Shinhan Youth Party

Robert G.

Grierson (Gu Rye-seon)

7.

A missionary who saved Koreans from dying from Japanese violence

Case File: '105 Cases'

Louis Marin

8.

A politician who supported the independence movement in Europe

Case File Gumi Committee

Chufuqing

9.

A revolutionary who provided material and spiritual support to key figures of the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea

Case File: Kim Gu's Refuge

George S.

McCune (Yoon San-on)

10.

The educator who maintained national pride by refusing to visit the Shinto shrine

Case File: Closure of Sungsil School

Part 3.

Righteous solidarity against imperialism

George L.

show

11.

A businessman who helped the provisional government despite arrests, detentions, and diplomatic disputes

Case File Andong Transportation Office

Fuse Tatsuji

12.

A lawyer who fought alongside Koreans in a Japanese court

Case File 2.8 Declaration of Independence

Fumiko Kaneko (Park Mun-ja)

13.

Anarchists who fought against both colonialism and human oppression

Case File: Great Kanto Earthquake

George A.

Peach (Bio-saeng 費吾生)

14.

A pastor who suffered together with Koreans following in the footsteps of his father

Case File: Yun Bong-gil's Uprising

Du Junhui

15.

A liberation activist who fought for Korean independence and women's rights.

Case File Korea-China Cultural Association

Part 1.

Commitment to restoring sovereignty

Oliver R.

Avison (Abyssin 魚丕信)

1.

A doctor who created a medical education system to lay the foundation for Joseon's independence.

Case File: Righteous Army Uprising

Robert D.

Story

2.

A journalist who exposed the violation of diplomatic sovereignty and informed the world.

Case file 'Eulsa Treaty'

Frederick A.

Mackenzie

3. Journalists who testified to the violation of sovereignty through “The Tragedy of the Korean Empire”

Case File: Righteous Army War

Homer B.

Hulbert (Hulbert Law)

4.

The "voluntary diplomats" who rushed to The Hague to reclaim diplomatic sovereignty.

Case File: Special Envoy of the International Peace Conference

Part 2.

Courage to protect Joseon

Frank W.

Schofield (Seok Ho-pil)

5.

A veterinarian who protected Joseon by documenting the Japanese military's oppression through photographs.

Case File: Je-Am-Ri Massacre

Huang Zhu

6.

A publisher with a solid network across Korea, China, and Japan

Case File Shinhan Youth Party

Robert G.

Grierson (Gu Rye-seon)

7.

A missionary who saved Koreans from dying from Japanese violence

Case File: '105 Cases'

Louis Marin

8.

A politician who supported the independence movement in Europe

Case File Gumi Committee

Chufuqing

9.

A revolutionary who provided material and spiritual support to key figures of the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea

Case File: Kim Gu's Refuge

George S.

McCune (Yoon San-on)

10.

The educator who maintained national pride by refusing to visit the Shinto shrine

Case File: Closure of Sungsil School

Part 3.

Righteous solidarity against imperialism

George L.

show

11.

A businessman who helped the provisional government despite arrests, detentions, and diplomatic disputes

Case File Andong Transportation Office

Fuse Tatsuji

12.

A lawyer who fought alongside Koreans in a Japanese court

Case File 2.8 Declaration of Independence

Fumiko Kaneko (Park Mun-ja)

13.

Anarchists who fought against both colonialism and human oppression

Case File: Great Kanto Earthquake

George A.

Peach (Bio-saeng 費吾生)

14.

A pastor who suffered together with Koreans following in the footsteps of his father

Case File: Yun Bong-gil's Uprising

Du Junhui

15.

A liberation activist who fought for Korean independence and women's rights.

Case File Korea-China Cultural Association

Detailed image

Into the book

A letter hidden in the trouser leg

In January, the story arrived in Busan via Kobe, Japan.

This was my first time setting foot on Korean soil as a correspondent for the Tribune.

The Tribune was founded in London on January 15, 1906, and was owned by Franklin Thomasson, a young Liberal MP and heir to a Bolton textile business.

This newspaper aimed to be a high-quality publication and received a lot of attention from young intellectuals, but it failed to overcome financial difficulties and was shut down on February 8, 1908, just two years after its launch.

The story of how he came to the Korean Empire was that he had a letter that could contact Emperor Gojong.

After arriving in Seoul, I finally managed to contact King Gojong.

The story goes that at the time, the palace was under strict surveillance by the Japanese and was teeming with spies, so Gojong could not freely communicate with even those close to him, and even his subjects were blocked by Japanese soldiers at the palace gates.

The content of the royal edict that the story first received from Emperor Gojong was a request to help prevent Emperor Gojong himself from being assassinated under the threat of Japan.

After receiving this royal edict, Story decided to trust only Emperor Gojong's royal edict, instead of relying on the information channels he had previously relied on.

This is because he judged that the only thing that could most clearly portray the situation in the Korean Empire was Emperor Gojong's letter, which was secretly delivered under strict surveillance by Japan.

To avoid the eyes of the Japanese intelligence agency, Story moved carefully, changing his accommodation every night.

Even during this time, people in the palace who were trusted by Emperor Gojong would secretly deliver letters by hiding them in their trouser legs.

Amidst this extreme vigilance and tension, at 4 a.m. one morning in January, a secret letter bearing Emperor Gojong's red seal was delivered to Story.

There is no record of how Gojong trusted him, but it is clear that after a long journey, the story eventually secured a path to direct communication with Gojong.

In this way, the story is about receiving a secret letter from Emperor Gojong and being given the important mission of breaking through Japan's surveillance network and revealing the truth about the Korean Empire to the world.

The secret letter, clearly stamped with Emperor Gojong's seal, consisted of six articles.

It contained the strong will of Emperor Gojong to deny the Eulsa Treaty.

The night he received the secret letter, Story safely escaped Seoul with the American Consul General.

--- 「Frederick A.

Mackenzie_ 2.

Among the journalists who testified about the violation of sovereignty through “The Tragedy of the Korean Empire”

Exchanges with Jo So-ang and Kim Sang-ok

In addition to his activities in the National Salvation Corps, Huang Zhu continued the New Child Alliance Party, which he had organized in Japan, in China.

In January 1920, the New A-Dong Alliance Party was reorganized into the 'Daedong Party'.

The Daedong Party adopted the Three Principles of Equality (三平主義), which centered on ethnic equality, national equality, and human equality.

About 3,000 people participated in the Datongdang, including Chinese people such as Zhang Mengjiu, Xu Deheng, and Zhou Pingqing, as well as Koreans, Indians, Japanese, and Russians.

In particular, he developed close relationships with Lee Dong-hui and Kim Lip, leaders of the Korean Socialist Party (Shanghai faction), through Park Jin-sun, and received much help from influential Koreans in Shanghai, including Kim Kyu-sik, Yeo Un-hyeong, Yun Hyeon-jin, and Kim Cheol, who also participated in the Daedong Party.

The Daedongdang not only supported the Korean independence movement, but also considered it an important part of their own work.

In this way, Huang Zhu consistently supported and assisted the revolutionary movement based on East Asian solidarity.

In this way, Hwang Je-woo's interest in and support for Joseon's independence movement was constant.

In particular, he frequently attended the March 1st Movement commemoration ceremony held in Shanghai.

There are three confirmed attendances, in 1925, 1928, and 1930, and he mainly gave speeches supporting Korean-Chinese solidarity and the independence movement.

He also appears to have been close friends with Jo So-ang.

When Jo So-ang published a biography of Kim Sang-ok, a member of the Uiyoldan who carried out the Jongno Police Station bombing incident, in Shanghai in 1925, Huang Jue wrote a preface for the Chinese people's condolence and eulogy sections honoring Kim Sang-ok's spirit.

It is said that before Kim Sang-ok's uprising, Jo So-ang introduced Kim Sang-ok to Hwang Je-woo.

In this way, Hwang Je-woo interacted widely with various Korean independence activists.

--- 「Huang Zhu_ 6.

Among the anti-Japanese activists who built a solid Korea-China network

Leading the French Korean Friendship Association

The French Korean Friends Association held its founding meeting on June 23, 1921, in the auditorium on the first floor of the Musee Social, 5, rue Las Cases, Paris.

The French Korean Friends Association was organized by Hwang Gi-hwan, who was in charge of diplomatic activities in Paris after Kim Kyu-sik, with the help of Felicien Chalaye and Scie Ton Fa, a Chinese national, and influential figures in the literary, artistic, and political circles.

Louis Marin was a leading figure in the French Korean Friendship Association and led its founding ceremony.

The founding conference was attended by 33 people, including six women, including Justin Godart, deputy for the Rhone region, Berthon, deputy for the Paris region, and the writer Claude Farrere.

Considering that there were letters read by those who could not attend, the size of the French Korean Friends Association at the time of its founding was likely slightly larger than the 33 attendees.

Although Louis Marin was the representative figure of the Korean Friendship Association, we must also remember Pericien Chalaye and Sa Dong-bal, who actively helped Hwang Gi-hwan organize the Korean Friendship Association.

Pericien Chalaye was born in Lyon on November 1, 1875, and passed the examination to become a professor of literature (specializing in philosophy) in 1897.

In the records of the provisional government, Pericien Chalaye, who was introduced as a professor at the University of Paris, visited colonial Korea twice in 1917 and 1919.

It appears that he experienced the reality of the March 1st Movement when he visited colonial Korea in 1919.

He wrote and gave speeches based on his experiences at that time, and the most representative example is his report on his observation of the Korean independence movement at the Paris Geography Research Association on January 8, 1920.

Sa Dong-bal, a Frenchman of Chinese descent, was born on December 5, 1880, in Paris, where his father, a Chinese diplomat, worked.

He received his doctorate in law and medicine from the University of Paris, but did not practice medicine.

He renounced his French citizenship in 1912 and enthusiastically supported the Korean independence movement, including serving as the secretary-general of the Korean Friends Association and providing funds.

Louis Marin stated at the founding convention that Korea, with a history spanning over 40 centuries, had always been non-aggressive, but when it was annexed in 1910 by Japan, which ignored international law, Koreans resisted and waited for independence.

He also explained the role of the Korean Friends Association, saying that France has always shown protection and affection for the oppressed, and that in order to provide effective assistance to Koreans, it must conduct active propaganda activities among the French public to secure many members.

--- 「Louis Marin_ 8.

Among the politicians who supported the independence movement in Europe

Fighting a legal battle against Japanese imperialism

There were two notable things that happened while I was in prison.

One is that Fumiko Kaneko wrote her autobiography while in prison.

This article was published in Japan in 1931 after Kaneko Fumiko's death under the title "What Made Me Like This?" (何が私をかうさせたか), allowing people to learn about her life and thoughts.

Another one is that Fumiko Kaneko legally married Park Yeol in prison.

The marriage application was submitted in late 1925 through the lawyer Tatsuji Fuse.

The reason they submitted marriage applications while in prison was because they wanted to be together as a family if they were sentenced to death for treason.

The first hearing of the treason trial against Kaneko Fumiko and Park Yeol was held on February 26, 1926.

Fumiko Kaneko, who attended the first trial, appeared wearing a white blouse and black skirt, with her hair tied back in a Joseon style.

Park Yeol wore a gauze hat and belt, court attire, and black shoes.

The two attended the trial wearing traditional Korean attire, and answered the judge's questions about their names using their Korean names.

Kaneko Fumiko's attendance at the trial in hanbok and with a Korean name was an act of solidarity and resistance, showing that although she was born Japanese, her life and actions were in line with those of the Korean people.

The outcome of the trial was practically predetermined, as they had not changed their attitude or position at all.

The trial was held in four stages from February 26 to March 1, and on March 25, the Tokyo Supreme Court sentenced Fumiko Kaneko and Park Yeol to death.

Fumiko Kaneko shouted "Hurrah" after hearing the verdict.

For Fumiko Kaneko, who sought to directly prove the injustice of Japanese imperialism through the death sentence, the death sentence must have been considered a victory.

--- 「Kaneko Fumiko_ 13.

From "Anarchists Against Colonialism and Human Oppression"

Women also bear political responsibility for the fate of their nation.

But his activities did not stop there.

Du Junhui, who did not give up her identity as a feminist, founded the monthly magazine “Working Women” (職業婦女) in Chongqing in 1944 and emphasized women’s social participation.

〈Working Women〉 was not just a magazine that dealt with women's work ethics or guidelines for life, but also emphasized women's political responsibility and civic role in wartime Chinese society.

Through her writings, she argued that women too must become politically responsible for the fate of their nation and humanity.

The following year, she was elected as the executive director of the China Women's Federation and played an active role as a representative of women's groups.

On August 15, 1945, with Japan's surrender, Korea was liberated from colonial rule.

This moment must have been an incredibly moving day for the independence activists.

But for Du Junhui, that joy was also the beginning of separation and uncertainty.

In December 1945, Kim Seong-suk returned to Korea as part of the second group of key figures in the Provisional Government.

He returned to his homeland, but Du Junhui and his three sons, especially the sick second son, could not leave with him.

She could not leave her son, who needed urgent treatment for peritonitis, alone, so she remained in China.

They probably believed that they would meet again in just a few months.

But the separation that was thought to be short ended up being a farewell that would never see each other again.

Kim Seong-suk remained active in Seoul during the division, Cold War, and political turmoil, and passed away in 1969.

Du Junhui held important positions in the education and women's sectors under the government of the People's Republic of China, and in 1956, she attended the 8th National Congress of the Communist Party of China as a representative of the women's sector.

She lived as a leading figure in China's women's movement and education movement, but passed away in 1981 at the age of 83.

In 2016, 35 years later, the South Korean government remembered his name by awarding him the Order of Merit for National Foundation.

It was a belated response to his life, which had cried out, “I am a daughter of Joseon,” and a small tribute to a woman’s life of solidarity and struggle that transcended borders, nationality, language, and history.

In January, the story arrived in Busan via Kobe, Japan.

This was my first time setting foot on Korean soil as a correspondent for the Tribune.

The Tribune was founded in London on January 15, 1906, and was owned by Franklin Thomasson, a young Liberal MP and heir to a Bolton textile business.

This newspaper aimed to be a high-quality publication and received a lot of attention from young intellectuals, but it failed to overcome financial difficulties and was shut down on February 8, 1908, just two years after its launch.

The story of how he came to the Korean Empire was that he had a letter that could contact Emperor Gojong.

After arriving in Seoul, I finally managed to contact King Gojong.

The story goes that at the time, the palace was under strict surveillance by the Japanese and was teeming with spies, so Gojong could not freely communicate with even those close to him, and even his subjects were blocked by Japanese soldiers at the palace gates.

The content of the royal edict that the story first received from Emperor Gojong was a request to help prevent Emperor Gojong himself from being assassinated under the threat of Japan.

After receiving this royal edict, Story decided to trust only Emperor Gojong's royal edict, instead of relying on the information channels he had previously relied on.

This is because he judged that the only thing that could most clearly portray the situation in the Korean Empire was Emperor Gojong's letter, which was secretly delivered under strict surveillance by Japan.

To avoid the eyes of the Japanese intelligence agency, Story moved carefully, changing his accommodation every night.

Even during this time, people in the palace who were trusted by Emperor Gojong would secretly deliver letters by hiding them in their trouser legs.

Amidst this extreme vigilance and tension, at 4 a.m. one morning in January, a secret letter bearing Emperor Gojong's red seal was delivered to Story.

There is no record of how Gojong trusted him, but it is clear that after a long journey, the story eventually secured a path to direct communication with Gojong.

In this way, the story is about receiving a secret letter from Emperor Gojong and being given the important mission of breaking through Japan's surveillance network and revealing the truth about the Korean Empire to the world.

The secret letter, clearly stamped with Emperor Gojong's seal, consisted of six articles.

It contained the strong will of Emperor Gojong to deny the Eulsa Treaty.

The night he received the secret letter, Story safely escaped Seoul with the American Consul General.

--- 「Frederick A.

Mackenzie_ 2.

Among the journalists who testified about the violation of sovereignty through “The Tragedy of the Korean Empire”

Exchanges with Jo So-ang and Kim Sang-ok

In addition to his activities in the National Salvation Corps, Huang Zhu continued the New Child Alliance Party, which he had organized in Japan, in China.

In January 1920, the New A-Dong Alliance Party was reorganized into the 'Daedong Party'.

The Daedong Party adopted the Three Principles of Equality (三平主義), which centered on ethnic equality, national equality, and human equality.

About 3,000 people participated in the Datongdang, including Chinese people such as Zhang Mengjiu, Xu Deheng, and Zhou Pingqing, as well as Koreans, Indians, Japanese, and Russians.

In particular, he developed close relationships with Lee Dong-hui and Kim Lip, leaders of the Korean Socialist Party (Shanghai faction), through Park Jin-sun, and received much help from influential Koreans in Shanghai, including Kim Kyu-sik, Yeo Un-hyeong, Yun Hyeon-jin, and Kim Cheol, who also participated in the Daedong Party.

The Daedongdang not only supported the Korean independence movement, but also considered it an important part of their own work.

In this way, Huang Zhu consistently supported and assisted the revolutionary movement based on East Asian solidarity.

In this way, Hwang Je-woo's interest in and support for Joseon's independence movement was constant.

In particular, he frequently attended the March 1st Movement commemoration ceremony held in Shanghai.

There are three confirmed attendances, in 1925, 1928, and 1930, and he mainly gave speeches supporting Korean-Chinese solidarity and the independence movement.

He also appears to have been close friends with Jo So-ang.

When Jo So-ang published a biography of Kim Sang-ok, a member of the Uiyoldan who carried out the Jongno Police Station bombing incident, in Shanghai in 1925, Huang Jue wrote a preface for the Chinese people's condolence and eulogy sections honoring Kim Sang-ok's spirit.

It is said that before Kim Sang-ok's uprising, Jo So-ang introduced Kim Sang-ok to Hwang Je-woo.

In this way, Hwang Je-woo interacted widely with various Korean independence activists.

--- 「Huang Zhu_ 6.

Among the anti-Japanese activists who built a solid Korea-China network

Leading the French Korean Friendship Association

The French Korean Friends Association held its founding meeting on June 23, 1921, in the auditorium on the first floor of the Musee Social, 5, rue Las Cases, Paris.

The French Korean Friends Association was organized by Hwang Gi-hwan, who was in charge of diplomatic activities in Paris after Kim Kyu-sik, with the help of Felicien Chalaye and Scie Ton Fa, a Chinese national, and influential figures in the literary, artistic, and political circles.

Louis Marin was a leading figure in the French Korean Friendship Association and led its founding ceremony.

The founding conference was attended by 33 people, including six women, including Justin Godart, deputy for the Rhone region, Berthon, deputy for the Paris region, and the writer Claude Farrere.

Considering that there were letters read by those who could not attend, the size of the French Korean Friends Association at the time of its founding was likely slightly larger than the 33 attendees.

Although Louis Marin was the representative figure of the Korean Friendship Association, we must also remember Pericien Chalaye and Sa Dong-bal, who actively helped Hwang Gi-hwan organize the Korean Friendship Association.

Pericien Chalaye was born in Lyon on November 1, 1875, and passed the examination to become a professor of literature (specializing in philosophy) in 1897.

In the records of the provisional government, Pericien Chalaye, who was introduced as a professor at the University of Paris, visited colonial Korea twice in 1917 and 1919.

It appears that he experienced the reality of the March 1st Movement when he visited colonial Korea in 1919.

He wrote and gave speeches based on his experiences at that time, and the most representative example is his report on his observation of the Korean independence movement at the Paris Geography Research Association on January 8, 1920.

Sa Dong-bal, a Frenchman of Chinese descent, was born on December 5, 1880, in Paris, where his father, a Chinese diplomat, worked.

He received his doctorate in law and medicine from the University of Paris, but did not practice medicine.

He renounced his French citizenship in 1912 and enthusiastically supported the Korean independence movement, including serving as the secretary-general of the Korean Friends Association and providing funds.

Louis Marin stated at the founding convention that Korea, with a history spanning over 40 centuries, had always been non-aggressive, but when it was annexed in 1910 by Japan, which ignored international law, Koreans resisted and waited for independence.

He also explained the role of the Korean Friends Association, saying that France has always shown protection and affection for the oppressed, and that in order to provide effective assistance to Koreans, it must conduct active propaganda activities among the French public to secure many members.

--- 「Louis Marin_ 8.

Among the politicians who supported the independence movement in Europe

Fighting a legal battle against Japanese imperialism

There were two notable things that happened while I was in prison.

One is that Fumiko Kaneko wrote her autobiography while in prison.

This article was published in Japan in 1931 after Kaneko Fumiko's death under the title "What Made Me Like This?" (何が私をかうさせたか), allowing people to learn about her life and thoughts.

Another one is that Fumiko Kaneko legally married Park Yeol in prison.

The marriage application was submitted in late 1925 through the lawyer Tatsuji Fuse.

The reason they submitted marriage applications while in prison was because they wanted to be together as a family if they were sentenced to death for treason.

The first hearing of the treason trial against Kaneko Fumiko and Park Yeol was held on February 26, 1926.

Fumiko Kaneko, who attended the first trial, appeared wearing a white blouse and black skirt, with her hair tied back in a Joseon style.

Park Yeol wore a gauze hat and belt, court attire, and black shoes.

The two attended the trial wearing traditional Korean attire, and answered the judge's questions about their names using their Korean names.

Kaneko Fumiko's attendance at the trial in hanbok and with a Korean name was an act of solidarity and resistance, showing that although she was born Japanese, her life and actions were in line with those of the Korean people.

The outcome of the trial was practically predetermined, as they had not changed their attitude or position at all.

The trial was held in four stages from February 26 to March 1, and on March 25, the Tokyo Supreme Court sentenced Fumiko Kaneko and Park Yeol to death.

Fumiko Kaneko shouted "Hurrah" after hearing the verdict.

For Fumiko Kaneko, who sought to directly prove the injustice of Japanese imperialism through the death sentence, the death sentence must have been considered a victory.

--- 「Kaneko Fumiko_ 13.

From "Anarchists Against Colonialism and Human Oppression"

Women also bear political responsibility for the fate of their nation.

But his activities did not stop there.

Du Junhui, who did not give up her identity as a feminist, founded the monthly magazine “Working Women” (職業婦女) in Chongqing in 1944 and emphasized women’s social participation.

〈Working Women〉 was not just a magazine that dealt with women's work ethics or guidelines for life, but also emphasized women's political responsibility and civic role in wartime Chinese society.

Through her writings, she argued that women too must become politically responsible for the fate of their nation and humanity.

The following year, she was elected as the executive director of the China Women's Federation and played an active role as a representative of women's groups.

On August 15, 1945, with Japan's surrender, Korea was liberated from colonial rule.

This moment must have been an incredibly moving day for the independence activists.

But for Du Junhui, that joy was also the beginning of separation and uncertainty.

In December 1945, Kim Seong-suk returned to Korea as part of the second group of key figures in the Provisional Government.

He returned to his homeland, but Du Junhui and his three sons, especially the sick second son, could not leave with him.

She could not leave her son, who needed urgent treatment for peritonitis, alone, so she remained in China.

They probably believed that they would meet again in just a few months.

But the separation that was thought to be short ended up being a farewell that would never see each other again.

Kim Seong-suk remained active in Seoul during the division, Cold War, and political turmoil, and passed away in 1969.

Du Junhui held important positions in the education and women's sectors under the government of the People's Republic of China, and in 1956, she attended the 8th National Congress of the Communist Party of China as a representative of the women's sector.

She lived as a leading figure in China's women's movement and education movement, but passed away in 1981 at the age of 83.

In 2016, 35 years later, the South Korean government remembered his name by awarding him the Order of Merit for National Foundation.

It was a belated response to his life, which had cried out, “I am a daughter of Joseon,” and a small tribute to a woman’s life of solidarity and struggle that transcended borders, nationality, language, and history.

--- 「Du Jun Hui_ 15.

Among the activists who advocated for Korean independence and women's rights

Among the activists who advocated for Korean independence and women's rights

Publisher's Review

'Memories that went unnoticed'

Another history of the independence movement we didn't know about

If foreign independence activists had enlightened us 100 years ago,

Today, 80 years later, we reveal them to the world!

It marked the 80th anniversary of liberation.

Every year, we have reflected on the 'meaning of Korean independence' through the arduous lives and dedication of independence activists.

Their lives, burning with passion for the liberation of their country even at the cost of self-sacrifice, remind us of the importance of a people forging their own destiny through freedom and will.

Now, the public is broadening its horizons of understanding of the lives and activities of more diverse independence activists and the independence movement as a whole.

But it's still not enough.

There are some unexpected figures who have been a light to us in the darkness for over 100 years, yet have gone unnoticed.

On the 80th anniversary of liberation, we finally want to reveal them to the world through “Although It’s Not My Country.”

Why didn't I know?

His + story

Why have we been so ignorant of foreign independence activists? There are many reasons, but examining the root of the problem ultimately leads to the question: "Who has monopolized the narrative of history?"

History that is recorded is always written in a way that those in power have chosen and constructed.

Within this structure, the stories of diverse groups, including women, workers, colonized people, and sexual minorities, have always been pushed to the margins of the mainstream narrative.

The perspectives that deal with the history of the Korean independence movement have also followed this narrative power framework, and as a result, foreign independence activists, even if they were Western white men, have not entered the center of our memories, but have remained on the periphery of history.

But now is the time to change that perspective.

It is 'perhaps' natural that Koreans fought for Korean independence, but we have been obscured by that 'naturalness' and have missed the narrative of true 'solidarity.'

Today, as we mark the 80th anniversary of liberation, it is time to actively restore memories that have previously gone unnoticed.

Foreign independence activists who fought for the independence of Joseon, a foreign land, beyond nationality and gender.

The fact that they threw themselves into the flames of imperialism was not simply a "struggle of strangers," but a testament to individual courage and human solidarity.

We must now ask again why they fought, and through that question, we must look anew at the meaning of solidarity.

It is here that we encounter the concept of global citizenship.

What is human solidarity? Its meaning is deeply intertwined with global citizenship.

The reason why these people, with different nationalities, languages, cultures, and livelihoods, were able to willingly stand up for Joseon's independence was because they had a sense of solidarity that transcended national boundaries, a sense of ethics and responsibility as global citizens.

This book, "Although Not My Country," brings back to life the traces of courage and solidarity they left behind, reviving their voices, long unheard, into a story we must tell anew today.

Why should I know?

Global Citizen (Gender)

So what exactly does global citizenship mean? The concept traces its roots to the ancient Greek philosopher Diogenes' declaration, "I am not a citizen of Athens, but a citizen of the world."

But today's global citizenship is no longer confined to philosophical thinking.

It has become a civic consciousness that we must acquire as we live in an age of global crisis and interdependence.

Global citizenship is an attitude of living beyond the confines of a particular nation or ethnicity, recognizing the shared responsibility and solidarity of humanity.

It emphasizes ethical responsibility that transcends political and geographical boundaries, and is a life attitude that considers not only “my country” but also “our world.”

Even today, war, discrimination, and oppression are not over.

Massacres are taking place around the world, and in industrial societies, foreign workers face structural violence and exclusion.

Faced with this reality, the choices and solidarity shown by foreign independence activists 80 years ago are still valid.

They have been speaking through their actions what it means to be a global citizen in the past.

We must now ask ourselves:

“What kind of global citizen am I living as now?” To answer this question, we must remember and shed light on them.

Their stories are not just history of the past, but a mirror that reflects how we should live today.

The independence movement of the Republic of Korea was never confined to the geographical boundaries of the Korean Peninsula.

Behind the independence movements that unfolded around the world, there was solidarity and participation from people around the world that transcended national borders and races.

Foreign independence activists demonstrated through their actions that the liberation of Korea was not merely a matter of one nation, but part of a global peace movement against imperialism.

They willingly sacrificed themselves for the independence of a foreign land, demonstrating firsthand the attitude of global citizens grounded in humanity. "Although It's Not My Country" introduces 15 global citizens.

Who are they?

Oliver R.

Avison (Abyssin 魚丕信) / Robert D.

Story / Frederick A.

Mackenzie / Homer B.

Hulbert (Hulbert Law)/Frank W.

Schofield (Suk Ho-pil 石虎弼) / Huang Jie / Robert G.

Grierson (Gu Rye-seon 具禮善) / Louis Marin / Chu Fucheng / George S.

McCune (Yoon San-on 尹山溫) George L.

Show / Fuse Tatsuji / Kaneko Fumiko (Park Mun-ja) / George A.

Peach (Fei Wu Sheng 費吾生) / Du Jun Hui

"Although It's Not My Country" illuminates the existence of practical solidarity that transcends national, linguistic, and cultural boundaries through the stories of 15 foreigners who dedicated themselves to Korea's independence movement.

As doctors, educators, journalists, and revolutionaries, they each responded to the realities of colonial Korea in their own ways.

Their choices, putting their beliefs into action and taking risks, prove that the concept of "global citizen" is not just an ideology, but a concrete attitude toward life.

The solidarity they showed cannot be explained by one-time sympathy or philanthropy.

The solidarity was a moral challenge to the imperialist system that defined the international order at the time, and it was the practice of universal ethics that recognized the suffering of one society as a problem for all of humanity.

They laid down their own privileges for the liberation of others and willingly threw themselves into fights that had nothing to do with the interests of their country.

That decision was not made 'for Joseon', but as a human being who fights against injustice.

Their traces do not remain in the records of the past.

The attitudes and values they left behind are still relevant today, even in the face of war, discrimination, and hatred.

We must now remember them not as foreigners who helped Joseon, but as practitioners of universal human values of justice and solidarity.

Their lives ask us:

“What kind of global citizen are you living as now?”

Another history of the independence movement we didn't know about

If foreign independence activists had enlightened us 100 years ago,

Today, 80 years later, we reveal them to the world!

It marked the 80th anniversary of liberation.

Every year, we have reflected on the 'meaning of Korean independence' through the arduous lives and dedication of independence activists.

Their lives, burning with passion for the liberation of their country even at the cost of self-sacrifice, remind us of the importance of a people forging their own destiny through freedom and will.

Now, the public is broadening its horizons of understanding of the lives and activities of more diverse independence activists and the independence movement as a whole.

But it's still not enough.

There are some unexpected figures who have been a light to us in the darkness for over 100 years, yet have gone unnoticed.

On the 80th anniversary of liberation, we finally want to reveal them to the world through “Although It’s Not My Country.”

Why didn't I know?

His + story

Why have we been so ignorant of foreign independence activists? There are many reasons, but examining the root of the problem ultimately leads to the question: "Who has monopolized the narrative of history?"

History that is recorded is always written in a way that those in power have chosen and constructed.

Within this structure, the stories of diverse groups, including women, workers, colonized people, and sexual minorities, have always been pushed to the margins of the mainstream narrative.

The perspectives that deal with the history of the Korean independence movement have also followed this narrative power framework, and as a result, foreign independence activists, even if they were Western white men, have not entered the center of our memories, but have remained on the periphery of history.

But now is the time to change that perspective.

It is 'perhaps' natural that Koreans fought for Korean independence, but we have been obscured by that 'naturalness' and have missed the narrative of true 'solidarity.'

Today, as we mark the 80th anniversary of liberation, it is time to actively restore memories that have previously gone unnoticed.

Foreign independence activists who fought for the independence of Joseon, a foreign land, beyond nationality and gender.

The fact that they threw themselves into the flames of imperialism was not simply a "struggle of strangers," but a testament to individual courage and human solidarity.

We must now ask again why they fought, and through that question, we must look anew at the meaning of solidarity.

It is here that we encounter the concept of global citizenship.

What is human solidarity? Its meaning is deeply intertwined with global citizenship.

The reason why these people, with different nationalities, languages, cultures, and livelihoods, were able to willingly stand up for Joseon's independence was because they had a sense of solidarity that transcended national boundaries, a sense of ethics and responsibility as global citizens.

This book, "Although Not My Country," brings back to life the traces of courage and solidarity they left behind, reviving their voices, long unheard, into a story we must tell anew today.

Why should I know?

Global Citizen (Gender)

So what exactly does global citizenship mean? The concept traces its roots to the ancient Greek philosopher Diogenes' declaration, "I am not a citizen of Athens, but a citizen of the world."

But today's global citizenship is no longer confined to philosophical thinking.

It has become a civic consciousness that we must acquire as we live in an age of global crisis and interdependence.

Global citizenship is an attitude of living beyond the confines of a particular nation or ethnicity, recognizing the shared responsibility and solidarity of humanity.

It emphasizes ethical responsibility that transcends political and geographical boundaries, and is a life attitude that considers not only “my country” but also “our world.”

Even today, war, discrimination, and oppression are not over.

Massacres are taking place around the world, and in industrial societies, foreign workers face structural violence and exclusion.

Faced with this reality, the choices and solidarity shown by foreign independence activists 80 years ago are still valid.

They have been speaking through their actions what it means to be a global citizen in the past.

We must now ask ourselves:

“What kind of global citizen am I living as now?” To answer this question, we must remember and shed light on them.

Their stories are not just history of the past, but a mirror that reflects how we should live today.

The independence movement of the Republic of Korea was never confined to the geographical boundaries of the Korean Peninsula.

Behind the independence movements that unfolded around the world, there was solidarity and participation from people around the world that transcended national borders and races.

Foreign independence activists demonstrated through their actions that the liberation of Korea was not merely a matter of one nation, but part of a global peace movement against imperialism.

They willingly sacrificed themselves for the independence of a foreign land, demonstrating firsthand the attitude of global citizens grounded in humanity. "Although It's Not My Country" introduces 15 global citizens.

Who are they?

Oliver R.

Avison (Abyssin 魚丕信) / Robert D.

Story / Frederick A.

Mackenzie / Homer B.

Hulbert (Hulbert Law)/Frank W.

Schofield (Suk Ho-pil 石虎弼) / Huang Jie / Robert G.

Grierson (Gu Rye-seon 具禮善) / Louis Marin / Chu Fucheng / George S.

McCune (Yoon San-on 尹山溫) George L.

Show / Fuse Tatsuji / Kaneko Fumiko (Park Mun-ja) / George A.

Peach (Fei Wu Sheng 費吾生) / Du Jun Hui

"Although It's Not My Country" illuminates the existence of practical solidarity that transcends national, linguistic, and cultural boundaries through the stories of 15 foreigners who dedicated themselves to Korea's independence movement.

As doctors, educators, journalists, and revolutionaries, they each responded to the realities of colonial Korea in their own ways.

Their choices, putting their beliefs into action and taking risks, prove that the concept of "global citizen" is not just an ideology, but a concrete attitude toward life.

The solidarity they showed cannot be explained by one-time sympathy or philanthropy.

The solidarity was a moral challenge to the imperialist system that defined the international order at the time, and it was the practice of universal ethics that recognized the suffering of one society as a problem for all of humanity.

They laid down their own privileges for the liberation of others and willingly threw themselves into fights that had nothing to do with the interests of their country.

That decision was not made 'for Joseon', but as a human being who fights against injustice.

Their traces do not remain in the records of the past.

The attitudes and values they left behind are still relevant today, even in the face of war, discrimination, and hatred.

We must now remember them not as foreigners who helped Joseon, but as practitioners of universal human values of justice and solidarity.

Their lives ask us:

“What kind of global citizen are you living as now?”

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: August 15, 2025

- Page count, weight, size: 300 pages | 140*220*20mm

- ISBN13: 9788920053658

- ISBN10: 8920053650

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)