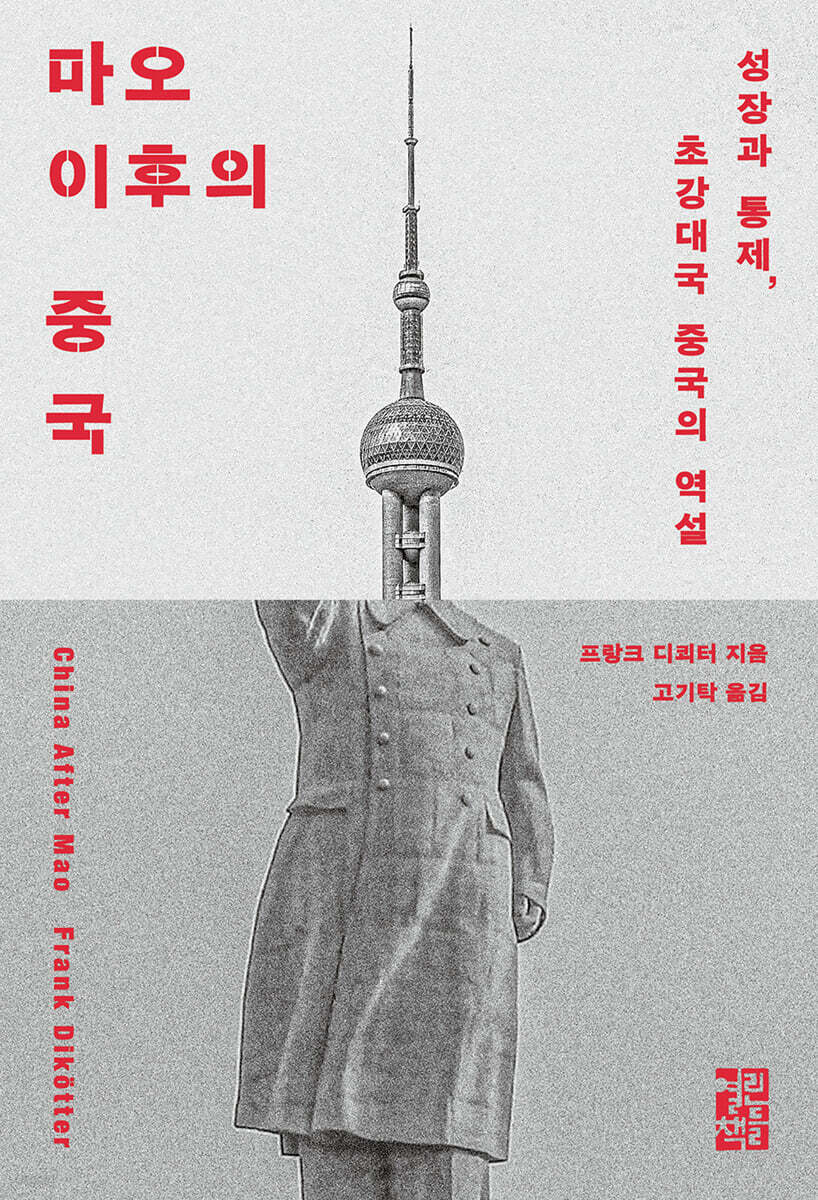

China after Mao

|

Description

Book Introduction

The Wall Street Journal, The Guardian, The Financial Times, etc.

A history book that has attracted the attention of numerous foreign media outlets

A leading researcher of modern Chinese history

Frank Dikötter's new work

1976-2020,

From Mao Zedong's death to Xi Jinping's rise to power

Analyzing the hidden side of modern China's "economic miracle"!

Frank Dikötter's "People's Trilogy", consisting of "The Tragedy of Liberation," "Mao's Great Famine," and "The Cultural Revolution," vividly portrayed the impact of Mao Zedong's communism on the lives of the Chinese people, winning the Samuel Johnson Award and opening up new horizons for the study of modern Chinese history.

Now the gaze turns to “after Mao.”

"China After Mao" is a historical book that reexamines China's "economic miracle" from Mao Zedong's death in 1976 to Xi Jinping's rise to power in 2020.

Drawing on a vast array of materials, from documents obtained from various Chinese archives to unpublished memoirs and secret diaries of key figures, DeKötter meticulously explores how the People's Republic of China rose to superpower status.

The assessment that the country achieved an economic miracle through orderly development under the leadership of the party is nothing more than a superficial narrative.

Behind the 40 years of rapid growth that have characterized modern history, lies powerful control, contradictions, illusions, and constant power struggles.

In particular, DeKötter focuses on the country's unilateral actions during the 2008 financial crisis, its hostility toward Western intervention, and its move toward becoming a dictatorship with one of the world's most sophisticated surveillance systems.

And ultimately, it concludes that the Communist Party's goal is not to join the democratic camp, but to resist it and gain the upper hand.

This book traces China's political and economic trajectory, providing essential insights for a deeper understanding of today's China.

A history book that has attracted the attention of numerous foreign media outlets

A leading researcher of modern Chinese history

Frank Dikötter's new work

1976-2020,

From Mao Zedong's death to Xi Jinping's rise to power

Analyzing the hidden side of modern China's "economic miracle"!

Frank Dikötter's "People's Trilogy", consisting of "The Tragedy of Liberation," "Mao's Great Famine," and "The Cultural Revolution," vividly portrayed the impact of Mao Zedong's communism on the lives of the Chinese people, winning the Samuel Johnson Award and opening up new horizons for the study of modern Chinese history.

Now the gaze turns to “after Mao.”

"China After Mao" is a historical book that reexamines China's "economic miracle" from Mao Zedong's death in 1976 to Xi Jinping's rise to power in 2020.

Drawing on a vast array of materials, from documents obtained from various Chinese archives to unpublished memoirs and secret diaries of key figures, DeKötter meticulously explores how the People's Republic of China rose to superpower status.

The assessment that the country achieved an economic miracle through orderly development under the leadership of the party is nothing more than a superficial narrative.

Behind the 40 years of rapid growth that have characterized modern history, lies powerful control, contradictions, illusions, and constant power struggles.

In particular, DeKötter focuses on the country's unilateral actions during the 2008 financial crisis, its hostility toward Western intervention, and its move toward becoming a dictatorship with one of the world's most sophisticated surveillance systems.

And ultimately, it concludes that the Communist Party's goal is not to join the democratic camp, but to resist it and gain the upper hand.

This book traces China's political and economic trajectory, providing essential insights for a deeper understanding of today's China.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

preface

1 Another Dictator (1976–1979)

2 Austerity (1979–1982)

3 Reforms (1982–1984)

4. By People and Price (1984-1988)

5 Massacre (1989)

6 Watershed (1989-1991)

7. A Capitalist Tool in the Hands of Socialism (1992–1996)

8 Big is Beautiful (1997-2001)

9 Globalization (2001–2008)

10 Oman (2008-2012)

Conclusion

Acknowledgements

main

Selected References

Search

1 Another Dictator (1976–1979)

2 Austerity (1979–1982)

3 Reforms (1982–1984)

4. By People and Price (1984-1988)

5 Massacre (1989)

6 Watershed (1989-1991)

7. A Capitalist Tool in the Hands of Socialism (1992–1996)

8 Big is Beautiful (1997-2001)

9 Globalization (2001–2008)

10 Oman (2008-2012)

Conclusion

Acknowledgements

main

Selected References

Search

Detailed image

Into the book

In the summer of 1985, when the movie "Back to the Future" was a box office hit, I, a student at the University of Geneva in Switzerland, headed to China to study Chinese.

--- From "First Sentence"

Deng Xiaoping frequently intervened to protect Chairman Mao's reputation.

He admitted that "some comrades point out that the mistakes made during the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution far surpassed those made by Stalin."

“However, our evaluation of Comrade Mao Zedong and Mao Zedong Thought is not about Mao Zedong as an individual, but cannot be separated from the entire history of our Party.” He concluded as follows:

“To tarnish Mao Zedong is to tarnish our Party.”

--- p.64

Fourteen cities, including Dalian, Tianjin, Shanghai, Wenzhou, and Guangzhou, have been opened and have effectively become special economic zones.

There was only one condition set by Beijing.

Having previously poured billions of yuan into propaganda, they were now unwilling or unable to provide more funding to the newly designated special economic zones.

“We gave you the freedom to be open,” Zhao Ziyang explained.

"Don't come to Beijing every time a problem arises." In effect, local governments gained more discretion in exchange for less pressure on central government resources, and this seemed like a win-win scenario.

--- p.124

Just after midnight, the Prime Minister appeared on television and read from a prepared manuscript.

“We must take firm and decisive action to bring a swift end to the chaos,” he declared.

“If we fail to bring this situation to a swift end and allow it to continue, there is a very high possibility that serious consequences will ensue that none of us would like to see.” Finally, martial law was declared.

--- p.193~194

Deng Xiaoping argued that the tools of capitalism would be safe in the hands of socialists.

But his vision for reform contained a contradiction, one that showed he was ignorant of even basic economic laws.

In a political system based on the separation of powers, the central bank possessed the so-called interest rate and the deposit rate as the main financial tools at its disposal, whereas under a socialist system, banks were subordinate to the state.

With the successive decentralizations that followed in 1979, local banks became unresponsive to either the market or central government plans.

They only followed the instructions given by the local party secretary.

Despite constant directives from the central government, there was no market discipline or party discipline.

Therefore, the regime, which had no intention of giving up control over the means of production, including capital, had only one option.

The goal was to take back the power that had been dispersed to local governments and impose discipline from the top down.

This required a dictator prepared to carry out purges, cut outs, burns, and punish on a scale sufficient to bring every local leader to their knees.

To borrow the expression of a local banker, “What this country needs is an enlightened Mao Zedong.”

--- p.269

In September 1997, Jiang Zemin announced that he would address the structural problems holding back the public sector.

In his speech at the 15th National Congress of the Communist Party of China, he summarized the party's new policy as follows:

This policy, which seemed to argue, “Catch the big ones and let the small ones go,” or “Big is beautiful,” called for eliminating thousands of small, inefficient factories and instead fostering giant corporations that would drive industry itself, much in the same way that South Korea fostered its chaebols.

Rather than allowing entrepreneurial passion to play a significant role, the party believed that Beijing's bureaucrats could select future winners and elevate them to higher levels through massive state capital injections.

In short, they planned to increase rather than minimize state intervention.

The message to state-owned enterprises was simple.

Expand or perish.

Officials in Beijing handpicked what they considered the best and biggest companies and showered them with preferential loans, development funds, and other forms of state support.

--- p.305

In April 2009, Zhou Xiaochuan, governor of the People's Bank of China, declared that China's swift response to the financial crisis demonstrated the superiority of its political system, challenging the US-led world order.

The Chinese leadership believed they had sufficiently proven their legitimacy.

And, mirroring the US government, it began to act as an advisor to the international community and provide guidance on how to run the economy.

They explained that the capitalist model was unsustainable and that it was time to pursue a new approach that would ultimately prove its superiority: “socialism with Chinese style.”

Hu Jintao called this “the Chinese way.”

--- p.387~388

Between 2010 and 2020, growth doubled, while debt tripled to 280 percent of GDP.

China's debt dependence had to be improved by shifting demand away from investment in infrastructure projects and towards more domestic consumption.

Yet, domestic demand could not grow any further for one very simple reason.

That is because most of the wealth flowed into the country, not the people.

As Li Keqiang pointed out in May 2020, more than 600 million people in China lived on $140 a month, barely enough to rent a room in a city.

To stimulate greater consumption, a massive redistribution of income to non-party members would have been necessary, but that seemed unlikely to happen.

--- From "First Sentence"

Deng Xiaoping frequently intervened to protect Chairman Mao's reputation.

He admitted that "some comrades point out that the mistakes made during the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution far surpassed those made by Stalin."

“However, our evaluation of Comrade Mao Zedong and Mao Zedong Thought is not about Mao Zedong as an individual, but cannot be separated from the entire history of our Party.” He concluded as follows:

“To tarnish Mao Zedong is to tarnish our Party.”

--- p.64

Fourteen cities, including Dalian, Tianjin, Shanghai, Wenzhou, and Guangzhou, have been opened and have effectively become special economic zones.

There was only one condition set by Beijing.

Having previously poured billions of yuan into propaganda, they were now unwilling or unable to provide more funding to the newly designated special economic zones.

“We gave you the freedom to be open,” Zhao Ziyang explained.

"Don't come to Beijing every time a problem arises." In effect, local governments gained more discretion in exchange for less pressure on central government resources, and this seemed like a win-win scenario.

--- p.124

Just after midnight, the Prime Minister appeared on television and read from a prepared manuscript.

“We must take firm and decisive action to bring a swift end to the chaos,” he declared.

“If we fail to bring this situation to a swift end and allow it to continue, there is a very high possibility that serious consequences will ensue that none of us would like to see.” Finally, martial law was declared.

--- p.193~194

Deng Xiaoping argued that the tools of capitalism would be safe in the hands of socialists.

But his vision for reform contained a contradiction, one that showed he was ignorant of even basic economic laws.

In a political system based on the separation of powers, the central bank possessed the so-called interest rate and the deposit rate as the main financial tools at its disposal, whereas under a socialist system, banks were subordinate to the state.

With the successive decentralizations that followed in 1979, local banks became unresponsive to either the market or central government plans.

They only followed the instructions given by the local party secretary.

Despite constant directives from the central government, there was no market discipline or party discipline.

Therefore, the regime, which had no intention of giving up control over the means of production, including capital, had only one option.

The goal was to take back the power that had been dispersed to local governments and impose discipline from the top down.

This required a dictator prepared to carry out purges, cut outs, burns, and punish on a scale sufficient to bring every local leader to their knees.

To borrow the expression of a local banker, “What this country needs is an enlightened Mao Zedong.”

--- p.269

In September 1997, Jiang Zemin announced that he would address the structural problems holding back the public sector.

In his speech at the 15th National Congress of the Communist Party of China, he summarized the party's new policy as follows:

This policy, which seemed to argue, “Catch the big ones and let the small ones go,” or “Big is beautiful,” called for eliminating thousands of small, inefficient factories and instead fostering giant corporations that would drive industry itself, much in the same way that South Korea fostered its chaebols.

Rather than allowing entrepreneurial passion to play a significant role, the party believed that Beijing's bureaucrats could select future winners and elevate them to higher levels through massive state capital injections.

In short, they planned to increase rather than minimize state intervention.

The message to state-owned enterprises was simple.

Expand or perish.

Officials in Beijing handpicked what they considered the best and biggest companies and showered them with preferential loans, development funds, and other forms of state support.

--- p.305

In April 2009, Zhou Xiaochuan, governor of the People's Bank of China, declared that China's swift response to the financial crisis demonstrated the superiority of its political system, challenging the US-led world order.

The Chinese leadership believed they had sufficiently proven their legitimacy.

And, mirroring the US government, it began to act as an advisor to the international community and provide guidance on how to run the economy.

They explained that the capitalist model was unsustainable and that it was time to pursue a new approach that would ultimately prove its superiority: “socialism with Chinese style.”

Hu Jintao called this “the Chinese way.”

--- p.387~388

Between 2010 and 2020, growth doubled, while debt tripled to 280 percent of GDP.

China's debt dependence had to be improved by shifting demand away from investment in infrastructure projects and towards more domestic consumption.

Yet, domestic demand could not grow any further for one very simple reason.

That is because most of the wealth flowed into the country, not the people.

As Li Keqiang pointed out in May 2020, more than 600 million people in China lived on $140 a month, barely enough to rent a room in a city.

To stimulate greater consumption, a massive redistribution of income to non-party members would have been necessary, but that seemed unlikely to happen.

--- p.431~432

Publisher's Review

The beginning of a historic transformation

Mao Zedong's death in 1976 marked the end of the Cultural Revolution.

The leadership sought a new order and set out to reorganize the system, using the Gang of Four as a scapegoat.

Nevertheless, Mao Zedong Thought was inherited out of strategic necessity.

Meanwhile, Deng Xiaoping, along with the restoration of national sovereignty, raised the banner of “socialist modernization” and formalized “reform and opening up.”

According to DeKötter, this is just another dictatorship.

In fact, instead of destroying the existing system, it only fine-tuned it.

The party still controlled all economic flows, and markets and banks operated according to political logic.

The structural contradictions of ultra-fast growth

By designating several areas, including Shenzhen and Zhuhai, as special economic zones, allowing foreign capital to flow in, and introducing a contractual responsibility system in rural areas, China entered a period of rapid growth.

In 1985, the industrial growth rate reached a whopping 22 percent, and urbanization and industrialization also accelerated.

While these are impressive figures, the growth was marred by accounting fraud and corruption.

Banks continued to lend recklessly, and inflation reached 23 percent in 1984.

DeKötter criticizes China's planned economy for lacking a "plan."

Only blind production, blind development, and blind procurement took place.

The future sealed in Tiananmen Square

Social discontent was rising.

The Wall of Democracy incident of 1978-1979 and the student protests of the 1980s briefly raised hopes for political reform, but the Tiananmen Square incident of 1989 crushed those hopes.

When hundreds of thousands of students and citizens took to the streets demanding freedom and democracy, the party leadership labeled it a “counterrevolutionary riot” instigated by hostile foreign forces and suppressed it with force.

Even after that, brutal oppression continued under the pretext of social stability.

Now China has been fanatically emphasizing only economic growth, while its people have been forced into silence.

China has degenerated from a country promising reform to a country exploiting the illusion of reform.

The Duality of Globalization Strategy

Entering the 1990s, Jiang Zemin pursued a strategy of “globalization.”

The return of Hong Kong to China in 1997 and its entry into the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001 gave China the appearance of being integrated into the international community, and foreign companies flocked to China, attracted by its cheap labor and vast domestic market.

DeKötter assesses that China has adhered to a dual strategy of expanding openness externally and expanding regulations internally.

At the time, banks continued to lend while hiding their deficits, local governments were busy speculating in real estate, and companies manipulated their accounting to inflate their performance.

Fragile systems, lax policies, and accumulated debt would only exacerbate and entrench chronic problems.

The evolution of propaganda and surveillance systems

The 2008 Beijing Olympics were a means to demonstrate the country's commitment to raising its international standing and improving its national image.

But the strong control-centered system became more solid.

The massive stimulus package implemented in response to the global financial crisis that same year served to re-validate the state-led economic model and increased confidence in the Chinese way.

Afterwards, Xi Jinping became more explicit in declaring that “China should not follow other countries,” clearly establishing an independent path.

At the same time, surveillance and censorship were strengthened across everything, including ideology, businesses, the media, and the Internet.

At the end of the book, DeKötter wrote:

"They seemed to have reached a dead end."

How should we understand modern Chinese history?

The world has long harbored an optimistic view that China's economic reforms will ultimately lead to political reform.

But DeKötter doggedly tracks what China has concealed and mobilized over the past 40 years, directly contradicting this conventional wisdom.

China is simply “pathologically fixated on a single number called growth rate while ignoring qualitative growth.”

He also points out that while “openness means the movement of people, ideas, goods, capital, etc.”, “China controls all of these flows and usually allows them to move in only one direction.”

"China After Mao" is a masterpiece that follows the "People's Trilogy," and it reveals in detail the truth about authoritarian rule hidden behind economic growth.

This will serve as a solid landmark for readers seeking to understand the challenges facing the massive nation of China and the profound impact it will have on the future restructuring of global power structures.

Mao Zedong's death in 1976 marked the end of the Cultural Revolution.

The leadership sought a new order and set out to reorganize the system, using the Gang of Four as a scapegoat.

Nevertheless, Mao Zedong Thought was inherited out of strategic necessity.

Meanwhile, Deng Xiaoping, along with the restoration of national sovereignty, raised the banner of “socialist modernization” and formalized “reform and opening up.”

According to DeKötter, this is just another dictatorship.

In fact, instead of destroying the existing system, it only fine-tuned it.

The party still controlled all economic flows, and markets and banks operated according to political logic.

The structural contradictions of ultra-fast growth

By designating several areas, including Shenzhen and Zhuhai, as special economic zones, allowing foreign capital to flow in, and introducing a contractual responsibility system in rural areas, China entered a period of rapid growth.

In 1985, the industrial growth rate reached a whopping 22 percent, and urbanization and industrialization also accelerated.

While these are impressive figures, the growth was marred by accounting fraud and corruption.

Banks continued to lend recklessly, and inflation reached 23 percent in 1984.

DeKötter criticizes China's planned economy for lacking a "plan."

Only blind production, blind development, and blind procurement took place.

The future sealed in Tiananmen Square

Social discontent was rising.

The Wall of Democracy incident of 1978-1979 and the student protests of the 1980s briefly raised hopes for political reform, but the Tiananmen Square incident of 1989 crushed those hopes.

When hundreds of thousands of students and citizens took to the streets demanding freedom and democracy, the party leadership labeled it a “counterrevolutionary riot” instigated by hostile foreign forces and suppressed it with force.

Even after that, brutal oppression continued under the pretext of social stability.

Now China has been fanatically emphasizing only economic growth, while its people have been forced into silence.

China has degenerated from a country promising reform to a country exploiting the illusion of reform.

The Duality of Globalization Strategy

Entering the 1990s, Jiang Zemin pursued a strategy of “globalization.”

The return of Hong Kong to China in 1997 and its entry into the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001 gave China the appearance of being integrated into the international community, and foreign companies flocked to China, attracted by its cheap labor and vast domestic market.

DeKötter assesses that China has adhered to a dual strategy of expanding openness externally and expanding regulations internally.

At the time, banks continued to lend while hiding their deficits, local governments were busy speculating in real estate, and companies manipulated their accounting to inflate their performance.

Fragile systems, lax policies, and accumulated debt would only exacerbate and entrench chronic problems.

The evolution of propaganda and surveillance systems

The 2008 Beijing Olympics were a means to demonstrate the country's commitment to raising its international standing and improving its national image.

But the strong control-centered system became more solid.

The massive stimulus package implemented in response to the global financial crisis that same year served to re-validate the state-led economic model and increased confidence in the Chinese way.

Afterwards, Xi Jinping became more explicit in declaring that “China should not follow other countries,” clearly establishing an independent path.

At the same time, surveillance and censorship were strengthened across everything, including ideology, businesses, the media, and the Internet.

At the end of the book, DeKötter wrote:

"They seemed to have reached a dead end."

How should we understand modern Chinese history?

The world has long harbored an optimistic view that China's economic reforms will ultimately lead to political reform.

But DeKötter doggedly tracks what China has concealed and mobilized over the past 40 years, directly contradicting this conventional wisdom.

China is simply “pathologically fixated on a single number called growth rate while ignoring qualitative growth.”

He also points out that while “openness means the movement of people, ideas, goods, capital, etc.”, “China controls all of these flows and usually allows them to move in only one direction.”

"China After Mao" is a masterpiece that follows the "People's Trilogy," and it reveals in detail the truth about authoritarian rule hidden behind economic growth.

This will serve as a solid landmark for readers seeking to understand the challenges facing the massive nation of China and the profound impact it will have on the future restructuring of global power structures.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: July 25, 2025

- Format: Hardcover book binding method guide

- Page count, weight, size: 528 pages | 908g | 162*231*34mm

- ISBN13: 9788932925288

- ISBN10: 8932925283

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)