Let's take up the hoe and pickaxe in the flower-covered garden.

|

Description

Book Introduction

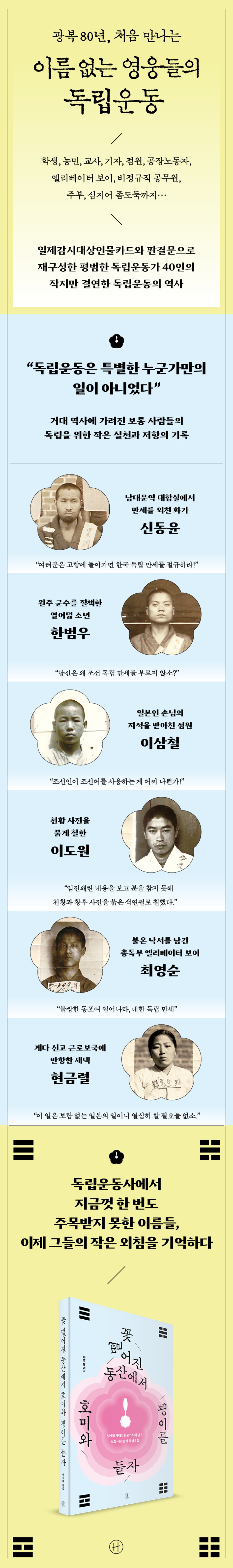

80 years since liberation, first meeting

The Independence Movement of Nameless Heroes

Students, farmers, teachers, journalists, clerks, factory workers,

Elevator boys, irregular workers, housewives, even petty thieves…

All that remains is a card the size of a hand and a verdict.

A record of the small but determined independence movement of 40 ordinary independence activists.

This book is a history of the independence movement of nameless heroes introduced in commemoration of the 80th anniversary of liberation.

It highlights the independence movement of 40 ordinary colonial Koreans whose history is recorded only through their Japanese surveillance cards and verdicts.

Students, teachers, local leaders, tenant farmers, clerks, elevator boys, irregular civil servants, housewives, and even thieves—everyday resistances in colonial Korea, regardless of occupation or status.

This record of small but determined resistance demonstrates that not only the independence movements of specific heroes, but also the small actions of ordinary people can have the power to change the present and history.

The Independence Movement of Nameless Heroes

Students, farmers, teachers, journalists, clerks, factory workers,

Elevator boys, irregular workers, housewives, even petty thieves…

All that remains is a card the size of a hand and a verdict.

A record of the small but determined independence movement of 40 ordinary independence activists.

This book is a history of the independence movement of nameless heroes introduced in commemoration of the 80th anniversary of liberation.

It highlights the independence movement of 40 ordinary colonial Koreans whose history is recorded only through their Japanese surveillance cards and verdicts.

Students, teachers, local leaders, tenant farmers, clerks, elevator boys, irregular civil servants, housewives, and even thieves—everyday resistances in colonial Korea, regardless of occupation or status.

This record of small but determined resistance demonstrates that not only the independence movements of specific heroes, but also the small actions of ordinary people can have the power to change the present and history.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

In publishing the book

1919 Shin Dong-yoon | The cheers of "Manse" echoed through the third-class waiting room.

1919 Lee Si-jong | Holding an underground newspaper and calling for independence

1919 Han Beom-woo | The Eighteen-Year-Old Who Reprimanded the Wonju County Governor

1920 Lee Su-hee | Young independence activists at Baehwa High School

1920 Oh Yong-jin | The Manse Plan that Remained Unwavering Despite Indifference

1921 Hwang Woong-do | Uniting the Hearts of Goseong Youth

1921 Kwon Ik-su | Forced to boycott the celebration

1922 Yoo Jin-hee | Korea's independence was achieved by the hands of the proletariat

1923 Hwang Don | A revolutionary who became a gun-wielding robber

1924 Song Byeong-cheon | A commemorative proclamation commemorating the March 1st Movement posted in Wonsan

1925 Kim Chang-jun | Showing off the power of the proletariat on Jongno Street

1926 Kim Ki-hwan | Proclamation of the 7th Anniversary of the March 1st Movement

1926 Hong Jong-hyeon | The Hidden Hero of the June 10th Independence Movement

1927 Im Hyeok-geun | Operation to establish the Iksan branch of the New People's Association

1928 Jeong Dong-hwa | Violently protesting colonial slave education

1928 Lee Do-won | Painted the Emperor's Photo Red

1929 Choi Guk-bong | Performing a play accusing city officials

1930 Im Jong-man | Students of Dangjin, Let's Shout "Manse"

1930 Choi Yong-bok | Teaching the Korean Boys Their Mission

1930 Kwon Young-ju | A revolutionary warrior confronted with reality

1931 Seo Jin | The Three Musketeers' Challenge to Build a New Society

1932 Choi Ik-han | The Failure of the Prisoner Transport Operation

1933 Lee Hyo-jeong | A literary girl at the forefront of the labor movement

1934 An Cheon-su | A rural farmer awakened by reading a magazine

Song Chang-seop, 1935 | Words of Independence Spread in Letters

1936 Lee Hong-chae | Imagining Independence through the Theory of National Reform

1936 Kim Jong-hee | A passionate young man who jumped into the literary movement

1937 Ham Yong-hwan | Samdoism's Bold Plan Targeting the Government-General

1937 Park Jae-man | Project to Cultivate Independent Talent in the Gangwon Mountains

1938 Yang Jun-gyu | Talking about Japan's defeat

1938 Hong Soon-chang | An elementary school teacher who refuted colonialist views

1939 Choi Young-sun | The elevator boy who left subversive graffiti

1940 Lee Je-guk | From a mere thief to an independence activist

1940 Park Ki-pyeong | Hope for Independence Gained by News from China

1940 Jeong Jae-cheol | Independence Movement Funds Given to a Swindler

1941 Do Young-hak | The dream of a true teacher frustrated by imperialization

1941 Cash Ryeol|Moreover, a newlywed who took on the task of serving the country through labor

1941 Kim Cheol-yong | A secret student organization disguised as a soccer club

1942 Lee Sam-cheol | Speaking Korean as a Korean

1943 Kim Myeong-hwa | Imperialism in the Old Site of Baekje

Notes/References in the Text

1919 Shin Dong-yoon | The cheers of "Manse" echoed through the third-class waiting room.

1919 Lee Si-jong | Holding an underground newspaper and calling for independence

1919 Han Beom-woo | The Eighteen-Year-Old Who Reprimanded the Wonju County Governor

1920 Lee Su-hee | Young independence activists at Baehwa High School

1920 Oh Yong-jin | The Manse Plan that Remained Unwavering Despite Indifference

1921 Hwang Woong-do | Uniting the Hearts of Goseong Youth

1921 Kwon Ik-su | Forced to boycott the celebration

1922 Yoo Jin-hee | Korea's independence was achieved by the hands of the proletariat

1923 Hwang Don | A revolutionary who became a gun-wielding robber

1924 Song Byeong-cheon | A commemorative proclamation commemorating the March 1st Movement posted in Wonsan

1925 Kim Chang-jun | Showing off the power of the proletariat on Jongno Street

1926 Kim Ki-hwan | Proclamation of the 7th Anniversary of the March 1st Movement

1926 Hong Jong-hyeon | The Hidden Hero of the June 10th Independence Movement

1927 Im Hyeok-geun | Operation to establish the Iksan branch of the New People's Association

1928 Jeong Dong-hwa | Violently protesting colonial slave education

1928 Lee Do-won | Painted the Emperor's Photo Red

1929 Choi Guk-bong | Performing a play accusing city officials

1930 Im Jong-man | Students of Dangjin, Let's Shout "Manse"

1930 Choi Yong-bok | Teaching the Korean Boys Their Mission

1930 Kwon Young-ju | A revolutionary warrior confronted with reality

1931 Seo Jin | The Three Musketeers' Challenge to Build a New Society

1932 Choi Ik-han | The Failure of the Prisoner Transport Operation

1933 Lee Hyo-jeong | A literary girl at the forefront of the labor movement

1934 An Cheon-su | A rural farmer awakened by reading a magazine

Song Chang-seop, 1935 | Words of Independence Spread in Letters

1936 Lee Hong-chae | Imagining Independence through the Theory of National Reform

1936 Kim Jong-hee | A passionate young man who jumped into the literary movement

1937 Ham Yong-hwan | Samdoism's Bold Plan Targeting the Government-General

1937 Park Jae-man | Project to Cultivate Independent Talent in the Gangwon Mountains

1938 Yang Jun-gyu | Talking about Japan's defeat

1938 Hong Soon-chang | An elementary school teacher who refuted colonialist views

1939 Choi Young-sun | The elevator boy who left subversive graffiti

1940 Lee Je-guk | From a mere thief to an independence activist

1940 Park Ki-pyeong | Hope for Independence Gained by News from China

1940 Jeong Jae-cheol | Independence Movement Funds Given to a Swindler

1941 Do Young-hak | The dream of a true teacher frustrated by imperialization

1941 Cash Ryeol|Moreover, a newlywed who took on the task of serving the country through labor

1941 Kim Cheol-yong | A secret student organization disguised as a soccer club

1942 Lee Sam-cheol | Speaking Korean as a Korean

1943 Kim Myeong-hwa | Imperialism in the Old Site of Baekje

Notes/References in the Text

Detailed image

Into the book

Shin Dong-yoon was one of the anonymous crowd that participated in the March 3rd Kaesong Manse demonstration.

Even though they cried out for independence, the Japanese Government-General of Korea was still in good shape and Korean independence seemed far away.

Shin Dong-yoon thought that it couldn't end like this.

I believed that if voices calling for independence continued to be raised not only in large cities like Seoul and Gaeseong, but also in remote rural areas, then something would change.

… On March 17, 1919, Shin Dong-yoon shouted this to the people in the third-class waiting room at Namdaemun Station.

"When you return to your hometowns, shout 'Long Live Korean Independence!' If there are no independence activists in each region, Korean independence cannot be expected!"

--- From "1919 Shin Dong-yoon|Cries of Manse Resounded in the Third-Class Waiting Room"

Lee Do-won was charged with one more unusual crime.

It was a crime of blasphemy.

In the fall of 1928, Lee Do-won, a sixth grader at Gongju Elementary School, was reading a reference book in the classroom.

At that time, national history meant Japanese history, so it seems to have been a reference book reflecting new research trends in Japanese history.

There was a story about the Imjin War, in which Toyotomi Hideyoshi invaded Joseon.

After reading this, Ido-won, unable to contain his anger, opened the page with the picture of the Emperor and Empress of the Japanese Empire, took a red pencil, and crossed out what was there so that it was impossible to tell what was there originally.

How did such a very private matter come to light?

--- From "1928 Lee Do-won | Painting the Emperor's Photograph Red"

The reason I wanted to summon Choi Ik-han, a giant in the independence movement, was to introduce an incident that occurred on July 8, 1932.

This is the incident of the Manse Uprising that occurred during the transfer of prisoners to Daejeon Prison, led by Choi Ik-han.

… On July 8, 1932, an operation to transfer 25 prisoners was carried out under the escort of four guards, including the head guard of Seodaemun Prison.

… (As the 25 prisoners) lined up and passed platform 1, Choi Ik-han suddenly shouted.

“Long live the Communist Party of Korea! Long live the liberation of the Korean people! Long live the independence of the Korean people!” Then the other prisoners joined in the shout.

…it was clear that punishment would follow, but the yearning for independence and revolution bursting from my heart was not calculated at all.

--- From "1932 Choi Ik-han | Making the Prisoner Transport Operation a Failure"

Ham Yong-hwan was born in Hosan-ri, Unsan-myeon, Yeonbaek-gun, Hwanghae-do in the year that the Eulmi Incident occurred.

She married Kim Moon-oh at the age of 14 and lived with him until she received a divine spirit in a dream around February 1932.

It was said that if you pray, you will have supernatural powers to achieve your wishes, such as wealth and having precious children.

This was in my late 30s.

… On March 8, 1937, twelve Samdoists, including Ham Yong-hwan, gathered.

At this point, Ham Yong-hwan said this.

“For the independence of Korea, at noon tomorrow the 9th, we will go to the front yard of the Government-General of Korea, leading the five-pointed star flag that not even enemy bullets can hit us, and shout ‘Long live the independence of Korea’ three times. Each of you, follow my orders.”

--- From "1937 Ham Yong-hwan | Samdo-gyo's Bold Plan Targeting the Government-General"

On May 1, 1940, Jongno Police Station was turned upside down.

This was because subversive graffiti was discovered on the wall of the west bathroom on the third floor of the Government-General of Korea.

“Poor compatriots, rise up! Long live Korean independence!” The Taegeuk mark, a symbol of Korea, was also included.

Although it was written in Japanese, it was clear to anyone that it was written by a Korean.

…The culprit was 18-year-old Choi Yeong-sun, an elevator operator working at the Government-General of Korea building.

…each elevator was assigned a so-called ‘elevator boy’.

Choi Young-sun was in charge of general use.

He commuted to and from work at Tonginjeong, ferrying key colonial officials up and down the road every day.

--- From "1939 Choi Young-sun | The Elevator Boy Who Left Subversive Graffiti"

Although Lee Je-guk was born in the golden land of Junghak-cho (now Junghak-dong) in Gyeongseong-bu, he was poor.

He attended elementary school until the 5th grade, but dropped out in March 1931 due to financial difficulties.

After that, unfortunately, he chose the life of a thief.

He served time in prison for theft in 1933 and for burglary and theft in 1937.

He was a so-called petty criminal.

… Lee Je-guk, who met Oh Dong-jin, was scolded.

"As a young Joseon man, shouldn't you consider being executed for a crime like the independence movement as your ultimate goal, rather than a heinous crime like theft?" Lee Je-guk felt ashamed by the words of this formidable independence activist and reflected deeply.

--- From "1940 Lee Je-guk | From a mere thief to an independence activist"

April 30, 1941 was the day when female members of the Labor Service Corps in Dongho-dong, Donghae-myeon, Gilju-gun, North Hamgyong Province were mobilized for the '1st Road Repair Work'.

However, something caught the eye of police officer Yuchon Du-mak, who was patrolling the construction site.

What caught his eye was a woman wearing geta.

… For the young bride, Hyun-Ryeol Hyeon, the notice to attend the Labor Service Corps must have been a very annoying thing.

I already had a mountain of chores to do, like cooking and doing laundry, so why were they calling me out for some damn road construction? And if I had a child to look after on top of that, I would be even angrier.

So, with a hint of rebellion and a nonchalant attitude, Hyun-chul went to the construction site wearing geta sandals.

--- From "1941 Cash Flow | A Newlywed Who Embarked on a Labor Service Mission"

Lee Sam-cheol, who had turned 17, lived and slept in the store's dormitory, visiting regular customers to take orders and running errands.

…while I was taking orders, Korean came out.

Born into a Korean family in a mountain village in Goesan County, Lee Sam-cheol was not able to receive formal Japanese education and would not have been familiar with Japanese.

Tsuru was very upset with Lee Sam-cheol's words and actions that mixed Japanese and Korean, and warned him about the proper use of Korean (Japanese).

However, Lee Sam-cheol did not tolerate the scolding.

“What’s wrong with Koreans speaking Korean? I’m not Japanese.

“I am Korean, so I speak Korean!”

Even though they cried out for independence, the Japanese Government-General of Korea was still in good shape and Korean independence seemed far away.

Shin Dong-yoon thought that it couldn't end like this.

I believed that if voices calling for independence continued to be raised not only in large cities like Seoul and Gaeseong, but also in remote rural areas, then something would change.

… On March 17, 1919, Shin Dong-yoon shouted this to the people in the third-class waiting room at Namdaemun Station.

"When you return to your hometowns, shout 'Long Live Korean Independence!' If there are no independence activists in each region, Korean independence cannot be expected!"

--- From "1919 Shin Dong-yoon|Cries of Manse Resounded in the Third-Class Waiting Room"

Lee Do-won was charged with one more unusual crime.

It was a crime of blasphemy.

In the fall of 1928, Lee Do-won, a sixth grader at Gongju Elementary School, was reading a reference book in the classroom.

At that time, national history meant Japanese history, so it seems to have been a reference book reflecting new research trends in Japanese history.

There was a story about the Imjin War, in which Toyotomi Hideyoshi invaded Joseon.

After reading this, Ido-won, unable to contain his anger, opened the page with the picture of the Emperor and Empress of the Japanese Empire, took a red pencil, and crossed out what was there so that it was impossible to tell what was there originally.

How did such a very private matter come to light?

--- From "1928 Lee Do-won | Painting the Emperor's Photograph Red"

The reason I wanted to summon Choi Ik-han, a giant in the independence movement, was to introduce an incident that occurred on July 8, 1932.

This is the incident of the Manse Uprising that occurred during the transfer of prisoners to Daejeon Prison, led by Choi Ik-han.

… On July 8, 1932, an operation to transfer 25 prisoners was carried out under the escort of four guards, including the head guard of Seodaemun Prison.

… (As the 25 prisoners) lined up and passed platform 1, Choi Ik-han suddenly shouted.

“Long live the Communist Party of Korea! Long live the liberation of the Korean people! Long live the independence of the Korean people!” Then the other prisoners joined in the shout.

…it was clear that punishment would follow, but the yearning for independence and revolution bursting from my heart was not calculated at all.

--- From "1932 Choi Ik-han | Making the Prisoner Transport Operation a Failure"

Ham Yong-hwan was born in Hosan-ri, Unsan-myeon, Yeonbaek-gun, Hwanghae-do in the year that the Eulmi Incident occurred.

She married Kim Moon-oh at the age of 14 and lived with him until she received a divine spirit in a dream around February 1932.

It was said that if you pray, you will have supernatural powers to achieve your wishes, such as wealth and having precious children.

This was in my late 30s.

… On March 8, 1937, twelve Samdoists, including Ham Yong-hwan, gathered.

At this point, Ham Yong-hwan said this.

“For the independence of Korea, at noon tomorrow the 9th, we will go to the front yard of the Government-General of Korea, leading the five-pointed star flag that not even enemy bullets can hit us, and shout ‘Long live the independence of Korea’ three times. Each of you, follow my orders.”

--- From "1937 Ham Yong-hwan | Samdo-gyo's Bold Plan Targeting the Government-General"

On May 1, 1940, Jongno Police Station was turned upside down.

This was because subversive graffiti was discovered on the wall of the west bathroom on the third floor of the Government-General of Korea.

“Poor compatriots, rise up! Long live Korean independence!” The Taegeuk mark, a symbol of Korea, was also included.

Although it was written in Japanese, it was clear to anyone that it was written by a Korean.

…The culprit was 18-year-old Choi Yeong-sun, an elevator operator working at the Government-General of Korea building.

…each elevator was assigned a so-called ‘elevator boy’.

Choi Young-sun was in charge of general use.

He commuted to and from work at Tonginjeong, ferrying key colonial officials up and down the road every day.

--- From "1939 Choi Young-sun | The Elevator Boy Who Left Subversive Graffiti"

Although Lee Je-guk was born in the golden land of Junghak-cho (now Junghak-dong) in Gyeongseong-bu, he was poor.

He attended elementary school until the 5th grade, but dropped out in March 1931 due to financial difficulties.

After that, unfortunately, he chose the life of a thief.

He served time in prison for theft in 1933 and for burglary and theft in 1937.

He was a so-called petty criminal.

… Lee Je-guk, who met Oh Dong-jin, was scolded.

"As a young Joseon man, shouldn't you consider being executed for a crime like the independence movement as your ultimate goal, rather than a heinous crime like theft?" Lee Je-guk felt ashamed by the words of this formidable independence activist and reflected deeply.

--- From "1940 Lee Je-guk | From a mere thief to an independence activist"

April 30, 1941 was the day when female members of the Labor Service Corps in Dongho-dong, Donghae-myeon, Gilju-gun, North Hamgyong Province were mobilized for the '1st Road Repair Work'.

However, something caught the eye of police officer Yuchon Du-mak, who was patrolling the construction site.

What caught his eye was a woman wearing geta.

… For the young bride, Hyun-Ryeol Hyeon, the notice to attend the Labor Service Corps must have been a very annoying thing.

I already had a mountain of chores to do, like cooking and doing laundry, so why were they calling me out for some damn road construction? And if I had a child to look after on top of that, I would be even angrier.

So, with a hint of rebellion and a nonchalant attitude, Hyun-chul went to the construction site wearing geta sandals.

--- From "1941 Cash Flow | A Newlywed Who Embarked on a Labor Service Mission"

Lee Sam-cheol, who had turned 17, lived and slept in the store's dormitory, visiting regular customers to take orders and running errands.

…while I was taking orders, Korean came out.

Born into a Korean family in a mountain village in Goesan County, Lee Sam-cheol was not able to receive formal Japanese education and would not have been familiar with Japanese.

Tsuru was very upset with Lee Sam-cheol's words and actions that mixed Japanese and Korean, and warned him about the proper use of Korean (Japanese).

However, Lee Sam-cheol did not tolerate the scolding.

“What’s wrong with Koreans speaking Korean? I’m not Japanese.

“I am Korean, so I speak Korean!”

--- From "1942 Lee Sam-cheol|Because I am Korean, I speak Korean"

Publisher's Review

1.

Ordinary People of Colonial Korea Become Heroes

―A record of the small acts of resistance and independence of ordinary people, hidden in the grand scheme of history.

From the painter Shin Dong-yoon who shouted "Manse" in the third-class waiting room, to the eighteen-year-old boy Han Beom-woo who reprimanded the Wonju county governor who tried to stop the Manse demonstration, to the student Jeong Dong-hwa who resisted colonial education through a strike, to the printer Song Byeong-cheon who posted a commemorative proclamation commemorating the March 1st Movement, to the farmer An Cheon-su who was awakened by reading a magazine, to the religious figure Ham Yong-hwan who planned the Manse demonstration in front of the Government-General, to the elevator boy Choi Yeong-sun who left subversive graffiti, to the thief-turned-independence activist Lee Je-guk, to the newlywed Hyeon Hyeon-ryeol who wore a geta and worked for the country, to the student secret society Kim Cheol-yong who created a soccer team disguised as a soccer club, to the clerk Lee Sam-cheol who was arrested for speaking Korean...

These are names that have never received attention in the history of the independence movement.

This book began with a curiosity about what it was like for ordinary people who had to live their daily lives in colonial Joseon, rather than famous independence activists.

This book departs from the narratives of famous independence activists or massive anti-Japanese movements that we often think of, and instead focuses on the everyday resistance and dedication of ordinary people in colonial Korea.

During the Japanese colonial period, the independence movement literally unfolded 'without rest' on the Korean Peninsula.

Some say that many colonial Koreans lived in compliance with Japanese rule, but many Koreans, angered by the controlled colonial life and daily discrimination, carried out the independence movement to the best of their ability in their respective positions.

When we examine the words and actions of ordinary people of various social statuses and occupations, we realize that the independence movement was not something only for special individuals.

This book shows what angered those who struggled to make ends meet and how that anger manifested itself in the independence movement. It proves the historical truth that the small voices and actions of ordinary people accumulate to bring about change in the times.

I thought that if I had been the chief of security in colonial Korea, I would have been in a really difficult situation.

This is because, no matter what measures were taken, voices calling for Korean independence continued to burst out.

… Some people highlight the gradual modernization of colonial Korea, and say that the majority of Koreans living on the Korean Peninsula complied with Japanese colonial rule.

But I am sure that if the spirits of the people introduced in this book heard these words, they would laugh.

There was a more important problem than improving institutions and raising living standards: living as a controlled colony.

…people who felt injustice in colonial life…whether young or old, regardless of the time period, these people came from all over the colony.

And their small cries pile up and become the foundation for independence.

―From “Preparing a Book” (pp. 6 and 7)

2.

The Stories of 40 Ordinary Independence Activists, Discovered from 4,837 Cards

―A history of a small but determined independence movement reconstructed using Japanese surveillance target cards and court rulings.

The stories in this book begin with the 'Japanese surveillance target card'.

This card first came to attention in 1965 when a photo of Yu Gwan-sun during her imprisonment was discovered in the warehouse of the Forensic Science Department of the Ministry of the Interior.

The source of the photo was a bundle of about 6,000 cards produced during the Japanese colonial period.

The Japanese wrote down the information of prisoners, wanted persons, and people under surveillance on cards and attached their photos to use them to suppress and arrest independence activists.

This bundle of cards, which had been kept by the Korean police after liberation, was transferred to the National Institute of Korean History in the late 1980s, and was finally given the name “Cards of Persons Under Japanese Surveillance” and its historical value was recognized.

Excluding the multiple cards, the number of people identified is 4,837, and all but 18 simple criminals are involved in the independence movement.

Although they are small cards, only about the size of a hand, the resonance each of them conveys is not small.

For example, Ahn Chang-ho had three cards written, and if you compare the first card from 1925 and the third card from 1937, you can imagine that he had aged 12 years because of his gaunt and changed appearance, to the point where you can't even tell that he was the same person.

In addition to the few independence activists whose names we remember, we can now call out the names of over 4,000 very ordinary independence activists.

This book traces the stories of those who were left with only one small card among countless others, restoring a new narrative of the independence movement.

Based on the prison records and information contained in the Japanese surveillance target cards, the book examines verdicts, investigation records, newspaper articles, and related research materials to reconstruct the stories of ordinary people who have not been recorded in history and provides a detailed portrayal of the independence movement in the daily lives of colonial Korea.

Ironically, this card, which was created by the Japanese to suppress the independence movement, has made it possible to learn the names and appearances of forgotten independence activists and to record a new history of the independence movement.

3.

80th Anniversary of Liberation: A History Connected to Today's Plaza

From small resistances in colonial daily life to a revolution of light

The year 2025, when this book is published, is a significant year, marking the 80th anniversary of liberation.

Furthermore, this book began as a timely project that allowed me to witness and experience the revolution of light that took place in the plaza from the winter of 2024 to the spring of 2025, and to feel the great power that small actions born from the wishes of ordinary people can wield.

The image of the citizens in the square today is an image of the ordinary people who raised their voices and took action in colonial Korea.

As someone once said, “Liberation is a history achieved through the sacrifice and dedication of ordinary people,” and the reason the light of hope for independence never waned was because of the wishes and ceaseless resistance of ordinary people.

This book conveys the historical lesson that connects the past and present, that we are the successors of a nation that resisted injustice and oppression and achieved independence, and that the small actions of ordinary people can bring about great change.

Ordinary People of Colonial Korea Become Heroes

―A record of the small acts of resistance and independence of ordinary people, hidden in the grand scheme of history.

From the painter Shin Dong-yoon who shouted "Manse" in the third-class waiting room, to the eighteen-year-old boy Han Beom-woo who reprimanded the Wonju county governor who tried to stop the Manse demonstration, to the student Jeong Dong-hwa who resisted colonial education through a strike, to the printer Song Byeong-cheon who posted a commemorative proclamation commemorating the March 1st Movement, to the farmer An Cheon-su who was awakened by reading a magazine, to the religious figure Ham Yong-hwan who planned the Manse demonstration in front of the Government-General, to the elevator boy Choi Yeong-sun who left subversive graffiti, to the thief-turned-independence activist Lee Je-guk, to the newlywed Hyeon Hyeon-ryeol who wore a geta and worked for the country, to the student secret society Kim Cheol-yong who created a soccer team disguised as a soccer club, to the clerk Lee Sam-cheol who was arrested for speaking Korean...

These are names that have never received attention in the history of the independence movement.

This book began with a curiosity about what it was like for ordinary people who had to live their daily lives in colonial Joseon, rather than famous independence activists.

This book departs from the narratives of famous independence activists or massive anti-Japanese movements that we often think of, and instead focuses on the everyday resistance and dedication of ordinary people in colonial Korea.

During the Japanese colonial period, the independence movement literally unfolded 'without rest' on the Korean Peninsula.

Some say that many colonial Koreans lived in compliance with Japanese rule, but many Koreans, angered by the controlled colonial life and daily discrimination, carried out the independence movement to the best of their ability in their respective positions.

When we examine the words and actions of ordinary people of various social statuses and occupations, we realize that the independence movement was not something only for special individuals.

This book shows what angered those who struggled to make ends meet and how that anger manifested itself in the independence movement. It proves the historical truth that the small voices and actions of ordinary people accumulate to bring about change in the times.

I thought that if I had been the chief of security in colonial Korea, I would have been in a really difficult situation.

This is because, no matter what measures were taken, voices calling for Korean independence continued to burst out.

… Some people highlight the gradual modernization of colonial Korea, and say that the majority of Koreans living on the Korean Peninsula complied with Japanese colonial rule.

But I am sure that if the spirits of the people introduced in this book heard these words, they would laugh.

There was a more important problem than improving institutions and raising living standards: living as a controlled colony.

…people who felt injustice in colonial life…whether young or old, regardless of the time period, these people came from all over the colony.

And their small cries pile up and become the foundation for independence.

―From “Preparing a Book” (pp. 6 and 7)

2.

The Stories of 40 Ordinary Independence Activists, Discovered from 4,837 Cards

―A history of a small but determined independence movement reconstructed using Japanese surveillance target cards and court rulings.

The stories in this book begin with the 'Japanese surveillance target card'.

This card first came to attention in 1965 when a photo of Yu Gwan-sun during her imprisonment was discovered in the warehouse of the Forensic Science Department of the Ministry of the Interior.

The source of the photo was a bundle of about 6,000 cards produced during the Japanese colonial period.

The Japanese wrote down the information of prisoners, wanted persons, and people under surveillance on cards and attached their photos to use them to suppress and arrest independence activists.

This bundle of cards, which had been kept by the Korean police after liberation, was transferred to the National Institute of Korean History in the late 1980s, and was finally given the name “Cards of Persons Under Japanese Surveillance” and its historical value was recognized.

Excluding the multiple cards, the number of people identified is 4,837, and all but 18 simple criminals are involved in the independence movement.

Although they are small cards, only about the size of a hand, the resonance each of them conveys is not small.

For example, Ahn Chang-ho had three cards written, and if you compare the first card from 1925 and the third card from 1937, you can imagine that he had aged 12 years because of his gaunt and changed appearance, to the point where you can't even tell that he was the same person.

In addition to the few independence activists whose names we remember, we can now call out the names of over 4,000 very ordinary independence activists.

This book traces the stories of those who were left with only one small card among countless others, restoring a new narrative of the independence movement.

Based on the prison records and information contained in the Japanese surveillance target cards, the book examines verdicts, investigation records, newspaper articles, and related research materials to reconstruct the stories of ordinary people who have not been recorded in history and provides a detailed portrayal of the independence movement in the daily lives of colonial Korea.

Ironically, this card, which was created by the Japanese to suppress the independence movement, has made it possible to learn the names and appearances of forgotten independence activists and to record a new history of the independence movement.

3.

80th Anniversary of Liberation: A History Connected to Today's Plaza

From small resistances in colonial daily life to a revolution of light

The year 2025, when this book is published, is a significant year, marking the 80th anniversary of liberation.

Furthermore, this book began as a timely project that allowed me to witness and experience the revolution of light that took place in the plaza from the winter of 2024 to the spring of 2025, and to feel the great power that small actions born from the wishes of ordinary people can wield.

The image of the citizens in the square today is an image of the ordinary people who raised their voices and took action in colonial Korea.

As someone once said, “Liberation is a history achieved through the sacrifice and dedication of ordinary people,” and the reason the light of hope for independence never waned was because of the wishes and ceaseless resistance of ordinary people.

This book conveys the historical lesson that connects the past and present, that we are the successors of a nation that resisted injustice and oppression and achieved independence, and that the small actions of ordinary people can bring about great change.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: July 28, 2025

- Page count, weight, size: 280 pages | 332g | 129*200*18mm

- ISBN13: 9791170873570

- ISBN10: 117087357X

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)