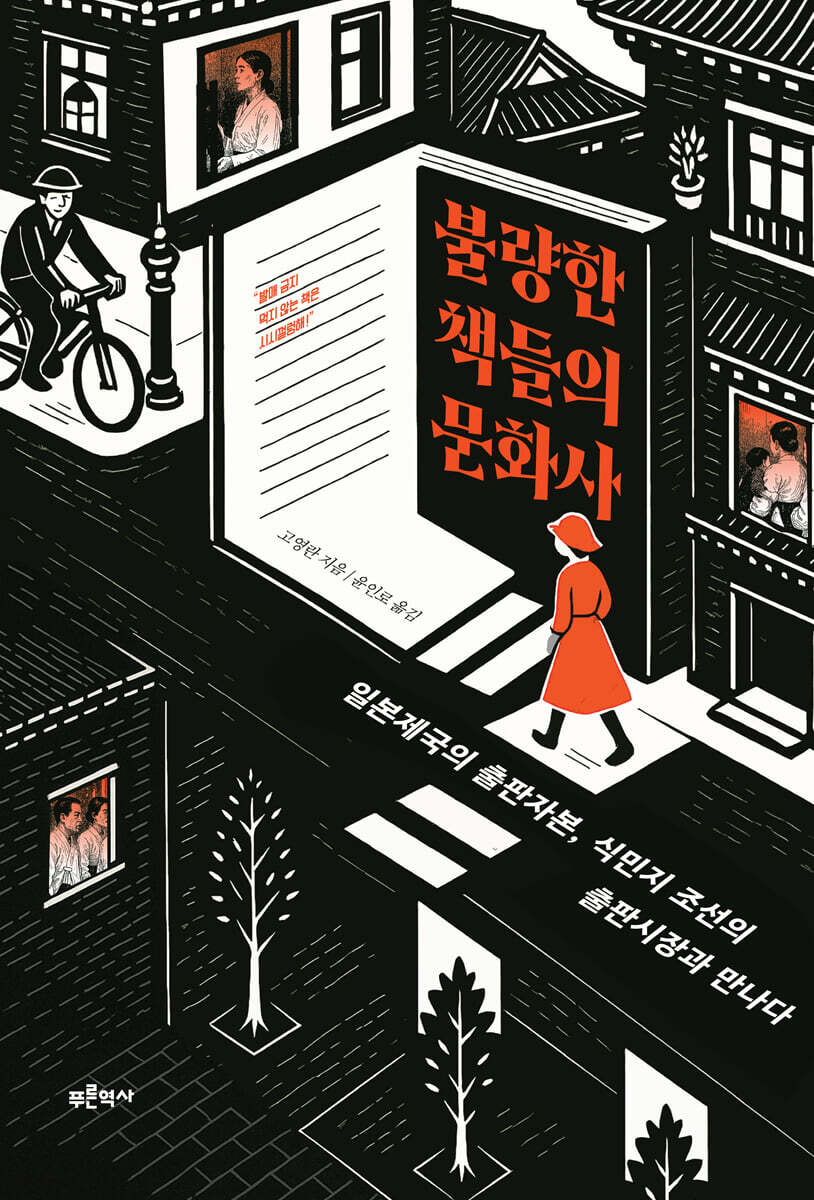

A Cultural History of Bad Books

|

Description

Book Introduction

Rewriting the History of Imperial Japan and Colonial Korea Through Publication

“Books that are banned from publication and don’t eat are boring!”

Reexamining the Cultural Encounters of Colonies and Empires

The author, who lectures on modern and contemporary Japanese literature in Japan, has been advocating for a rewriting of the modern history of the Japanese Empire.

As a result, he produced works such as 『The Ideology of Postwar』 (Korean edition, 2013, Hyunsilmunhwa) and 『Empire of Censorship』 (Korean edition, 2016, Blue History).

Here, Japan's modern history, constructed through the frame of "postwar," was established by the consciousness of the victims of the defeated nation, Japan, and even the experiences of the "colonial subjects" of the Korean Peninsula were used as metaphors to explain their own discourse of sacrifice, revealing how the memory of colonial rule was forgotten.

This book is an extension of the author's research activities.

Imperial studies in Korea lack a broad perspective on the entirety of Imperial Japan and an analysis of how Japanese and Korean sources are intricately intertwined and intertwined.

By meticulously examining data from both countries and overcoming these limitations, the author focused on aspects that cannot be captured by the dichotomous thinking of perpetrator and perpetrator, such as the positive role of the Japanese language, that is, the fact that through the Japanese language, people learned how to resist Japan, as opposed to the dichotomous thinking of perpetrator and victim, which is strongly at work in areas such as publication censorship.

“Books that are banned from publication and don’t eat are boring!”

Reexamining the Cultural Encounters of Colonies and Empires

The author, who lectures on modern and contemporary Japanese literature in Japan, has been advocating for a rewriting of the modern history of the Japanese Empire.

As a result, he produced works such as 『The Ideology of Postwar』 (Korean edition, 2013, Hyunsilmunhwa) and 『Empire of Censorship』 (Korean edition, 2016, Blue History).

Here, Japan's modern history, constructed through the frame of "postwar," was established by the consciousness of the victims of the defeated nation, Japan, and even the experiences of the "colonial subjects" of the Korean Peninsula were used as metaphors to explain their own discourse of sacrifice, revealing how the memory of colonial rule was forgotten.

This book is an extension of the author's research activities.

Imperial studies in Korea lack a broad perspective on the entirety of Imperial Japan and an analysis of how Japanese and Korean sources are intricately intertwined and intertwined.

By meticulously examining data from both countries and overcoming these limitations, the author focused on aspects that cannot be captured by the dichotomous thinking of perpetrator and perpetrator, such as the positive role of the Japanese language, that is, the fact that through the Japanese language, people learned how to resist Japan, as opposed to the dichotomous thinking of perpetrator and victim, which is strongly at work in areas such as publication censorship.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Preface to the Korean edition

Preface: Rewriting the Cultural History of the Japanese Empire from the Perspective of Colonial Korea

Chapter 1 The Proletariat

1.

The Communist Manifesto and the Common People

2.

Slow Media in the Information Warfare Era: The Pyeongmin Newspaper

3.

Common peddlers fight against 'Russian spies'

4.

The Ambiguous Line between the 'New/Pleinian' and the Joseon People

Chapter 2 Library

1.

The era of book burning and 'no library'

2.

Cultural Politics and the Normalization of the Korean Language

3.

To fan the flames of aspirations from/to the empire

4.

A space called a night market or street vendor

Chapter 3: The Immortal

1.

A new word in the politics of the Governor-General of Joseon

2.

The Battle Between Imperial Media and Dark Media

3.

The gap between legal jurisdictions and subversive information warfare

4.

Fumiko Kaneko, Park Yeol, and the "Futeisenjin"

Chapter 4 Censorship

1.

Shinagawa Station in the Rain: The Diverging Fates of Korean and Japanese

2.

The positive role of mainland Japan and the Japanese language

3.

The Birth of a Censorship Empire

Chapter 5 Capital

1.

The added value of being banned: The magazines "Electric Battle Flag" and "Crab Processing Line"

2.

The magazine "Electricity" and the capitalization of illegal goods

3.

Catalog of Illegal Goods, "Electricity"

4.

The "Bulyeongseonin" as a mobile medium and the colonial market

Chapter 6 Colonies

1.

Yamamoto Sanehiko's Manchuria and Korea

2.

The banquet of "Remodeling" and "Dong-A Ilbo"

3.

Learning Socialism from the Reformers

4.

The transformation of the remodeler

5.

New products called Manchuria and Joseon

Chapter 7 Translation

1.

Translation as a symbol of internal and external unity

2.

The magazine "Munjang" and the "Frontline Literature Line" from mainland Japan

3.

The Front Line of Imperial Novelist Hayashi Fumiko

4.

Women's internal unity

5.

Joseon's Hayashi Fumiko and Choi Jeong-hee

Chapter 8 War

1.

The all-out war of the old empire and the surge in military stock prices

2.

Solitude in the Square and Colonial Japan

3.

Korean War without Koreans

4.

Jang Hyuk-ju's Korean War service account

5.

Japan is on no one's side

Conclusion: Questions about modern and contemporary Japanese cultural history

Translator's Note

main

List of first sunrises

Search

Preface: Rewriting the Cultural History of the Japanese Empire from the Perspective of Colonial Korea

Chapter 1 The Proletariat

1.

The Communist Manifesto and the Common People

2.

Slow Media in the Information Warfare Era: The Pyeongmin Newspaper

3.

Common peddlers fight against 'Russian spies'

4.

The Ambiguous Line between the 'New/Pleinian' and the Joseon People

Chapter 2 Library

1.

The era of book burning and 'no library'

2.

Cultural Politics and the Normalization of the Korean Language

3.

To fan the flames of aspirations from/to the empire

4.

A space called a night market or street vendor

Chapter 3: The Immortal

1.

A new word in the politics of the Governor-General of Joseon

2.

The Battle Between Imperial Media and Dark Media

3.

The gap between legal jurisdictions and subversive information warfare

4.

Fumiko Kaneko, Park Yeol, and the "Futeisenjin"

Chapter 4 Censorship

1.

Shinagawa Station in the Rain: The Diverging Fates of Korean and Japanese

2.

The positive role of mainland Japan and the Japanese language

3.

The Birth of a Censorship Empire

Chapter 5 Capital

1.

The added value of being banned: The magazines "Electric Battle Flag" and "Crab Processing Line"

2.

The magazine "Electricity" and the capitalization of illegal goods

3.

Catalog of Illegal Goods, "Electricity"

4.

The "Bulyeongseonin" as a mobile medium and the colonial market

Chapter 6 Colonies

1.

Yamamoto Sanehiko's Manchuria and Korea

2.

The banquet of "Remodeling" and "Dong-A Ilbo"

3.

Learning Socialism from the Reformers

4.

The transformation of the remodeler

5.

New products called Manchuria and Joseon

Chapter 7 Translation

1.

Translation as a symbol of internal and external unity

2.

The magazine "Munjang" and the "Frontline Literature Line" from mainland Japan

3.

The Front Line of Imperial Novelist Hayashi Fumiko

4.

Women's internal unity

5.

Joseon's Hayashi Fumiko and Choi Jeong-hee

Chapter 8 War

1.

The all-out war of the old empire and the surge in military stock prices

2.

Solitude in the Square and Colonial Japan

3.

Korean War without Koreans

4.

Jang Hyuk-ju's Korean War service account

5.

Japan is on no one's side

Conclusion: Questions about modern and contemporary Japanese cultural history

Translator's Note

main

List of first sunrises

Search

Into the book

When the word "proletariat" was imported into Japan, the class assumed by the translators almost overlapped with the "group of Japanese men" described by Fujino Yuko, and from the beginning, "Chosunjin" was not even considered.

The attempt to apply the concept of proletariat to Japan was made through the translation of Marx and Engels' "Communist Manifesto" [1848].

The first people to translate the Communist Manifesto into Japanese were Shusui Kotoku and Toshihiko Sakai.

--- p.29

Sakai recalls the circumstances surrounding his initial choice of 'commoner' as a translation for 'Proletarier':

“Among the translated words, the most prominent today are the words ‘gentleman’ and ‘commoner,’ whose original words are bourgeois and proletariat.

When we think of the common people's newspaper of the time, the common people's newspaper, 'Pyeongmin Shinmun', we can see that the translation word 'Pyeongmin' captures the feeling well.

However, at the time, ‘common people’ alone was not enough for me, and for this reason, in other places I also wrote ‘common people, that is, the modern working class.’”

--- p.34

This is the cover of “Diary of a Socialist Peddler” (Shinsensha, 1971), edited by Arahata Kanson. The cart being pulled by two young men is identical in form to the milk carts used during the Russo-Japanese War.

The first description of this cart can be found in the March 13, 1904, issue of the Pyeongmin Newspaper, in the column titled “News of Peddling Missionary Work.”

The two men traveled the country on foot, holding rallies and selling 'socialist literature' that they carried in a cart.

--- p.46

The peddler's travel expenses were covered by selling commoners' books purchased at half price.

In addition to selling to individual readers of the Pyeongmin Newspaper and Jikyeon and visiting socialist organizations across the country, they also recruited members of the Socialist Association by holding talks and lectures.

--- p.49

The term "common people" used by the "Pyeongmin Shinmun" and "Jikon" referred to the Japanese proletariat, especially the "comrade-reader community" of the Pyeongmin Society and the socialist movement.

This 'commoner' does not include the Baekjeong class, who were not treated as human beings even in modern Japanese society, where the emancipation edict was issued.

Socialists also criticized discrimination against the Burakumin, but called them 'new commoners' to distinguish them from the 'commoners'.

Under the same structure, the 'Joseon people' who were placed in the same position as the 'new commoners' were also never considered as such 'commoners'.

--- p.63

In the 1910s, about 20 private libraries were established across the country since the opening of Gyeongseong Library in 1909.

However, it seems that the number was not enough for the people of Bumin.

According to the results of a survey titled “What do you want in Gyeongseong?” published in the evening edition of the June 7, 1916 edition of the Gyeongseong Ilbo, the organ of the Government-General of Korea, the responses were as follows: ① a public hall (1,032 people), ② a Japanese-Korean social organization (987 people), ③ traffic restrictions to prevent congestion in Honmachi (978 people), ④ a library (962 people), ⑤ an art museum (947 people), ⑥ a theater (918 people), and ⑦ a private middle school (906 people).

--- p.71

The permission to publish Korean newspapers such as the Dong-A Ilbo and the Chosun Ilbo was met with much criticism from various quarters at the time.… However, I believed that the newspapers published by the Governor-General alone were not enough to understand the mood of the Korean people.… Even if they were somewhat opposed, I believed that if they did not fundamentally harm public order, they should be permitted, and that is why I permitted the Korean newspapers.

--- p.80

Around this time, the pages of Korean-language newspapers such as the Dong-A Ilbo and the Chosun Ilbo, which were at the forefront of the Hangul movement, were filled with advertisements for Japanese books.

Advertisements for Japanese books, which were linked to the movement to popularize the Korean language and the Japanese language, coexisted amicably in the same space and gained influence.

--- p.82

After World War I, the Keijo Imperial University Library used German reparations to collect materials and research papers from China and various European countries, and even transferred the collection of the Kyujanggak, the royal library of Joseon, which had been under the jurisdiction of the Government-General since 1910.… Keijo Imperial University’s collection… rapidly increased to 350,000 volumes in 1932.

This was more than the combined collection of books from all public and private vocational schools in Joseon.

In 1938… it ranked 5th in terms of the number of books in the entire Japanese Empire.

--- p.86

If you look at Korean newspapers from the 1920s, you can see many advertisements for Japanese-language exam preparation books and study guides.

As previously mentioned, this was because there were not enough schools that allowed Koreans to enroll while the educational fervor was boiling.

Among the advertisements in the Dong-A Ilbo, the top seven were occupied by the Waseda University Seven Lectures series, which emphasized the possibility of self-study of middle school courses.

--- p.91

Let’s read the article titled “3,000 Books Burned to Smoke on the Bank of the Taedong River” published in the August 15, 1933 edition of the Dong-A Ilbo.

“…Book burning is not something that can only be seen in ancient times, such as during the Qin Shi Huang era or in faraway Germany. It is said that in a few days, 3,000 books will turn into smoke along the Taedong River in Pyongyang.

These are the things that have been confiscated from Pyongyang so far… Among them, most of them are social science books that are difficult to obtain, including the problematic books “The Trial” and “The Last Day” published by the Japanese Lighthouse Company, and it is said that there are also “erotic” books that will make you lose your mind.

--- p.95

The word 'Seonin' was a new word (in Japanese) created by the ruling policy of the Government-General after the annexation of Korea.

The notation of the 'Korea-Japan Annexation Treaty' promulgated on August 29, 1910 was unified as 'Korea' and 'Koreans'.

However, on the same day, by royal decree, 'the name of Korea was changed and from now on it would be called Joseon.'

Thus, first of all, the use of the words ‘Daehan’ and ‘Emperor’ was prohibited in all official documents and place names.… Books with the word ‘Daehan’ in their titles were confiscated and some of them were burned.

--- p.107

According to Imamura Tomoe, the term 'Bulyeongseonin' is a coined word of the Police Affairs Bureau of the Government-General of Korea.… If you search for 'Bulyeongseonin' in the 'Korean History Database' and the 'Korean History Information Integration System', you will see that it was used as a term to map people who participated in the anti-Japanese movement in Japanese official documents.… You can see that the use of the term 'Bulyeongseonin' gradually increased from around 1910.

--- p.113

In the case of (underground) 'newspapers', there are more than 30 published between March and July 1919.

Including those published overseas, there are over 60. The underground media outlet <Independence Newspaper>, which was published during the March 1st Independence Movement, became a source of information for the people, no less than the Declaration of Independence, with over 10,000 copies distributed in Seoul on March 1st alone.

--- p.125

The January 1, 1923 edition of the Chosun Ilbo mentions Japanese books as symbolizing the reading trend that reached a major turning point in 1922.

Here, “Marx’s ‘Economics,’ ‘Liberation,’ and ‘Reformation’ were covered, and they sold out like hotcakes as soon as they were published… There were more cases where they sold out or went out of print.”

--- p.133

Half a year before the Great Kanto Earthquake, Fumiko Kaneko and Park Yeol confessed that misunderstandings about the "Bulyeongseonin" were serious.

They worried about “what will become of the world in the future?”

The massacre of Koreans during the Great Kanto Earthquake was not an accident.

In the end, “Hyunsaehoe” was also discontinued after being published twice, and that was the last time that Kaneko and Park Yeol jointly published a media.

However, the 'Bulyeongseonin' did not disappear.

--- p.142

The opening of the era of Korean language media was accompanied by the reorganization and strengthening of censorship by the Japanese Government-General of Korea.

… However… this should not be thought of as a stereotypical equation of ‘seizure = oppression = resistance (anti-Japanese)’.

In the first place, the Chosun Ilbo was created by the Taisho Society, a representative pro-Japanese organization.

However, since then, the Dong-A Ilbo has been subjected to 30 seizures, 23 arrests, and two long-term suspensions.

Existing studies rely solely on these numbers to highlight the damage done to the Chosun Ilbo and miss the nature of the media itself.

--- p.160

The publication policy of the Government-General of Korea was centered on publication and confiscation in the 1910s, and censorship in the 1920s.

To counter this, Korean literature was published in newspapers, magazines, and books in the United States, China, Manchuria, Russia, and other countries.… The Japanese mainland became a factory where the “uncivilized” people produced “subversive” Korean media.

The majority of publications were about socialism.

--- p.164

In 1925, the Japan Proletarian Cultural League was formed.

From this period until the collapse of the Japan Proletarian Cultural Federation in 1934, the heyday of the Japanese proletarian cultural movement was upon us.

A representative magazine of this period is “Jeongi War Flag.”

--- p.180

The main competitors of the 'leftist publishers' who must aim for the pocket money of 'innocent students' are 'bourgeois' publishers such as Gaejosa and Joongangongron, which are busy commercializing 'socialism'.

For example, the fierce competition between the “left-wing publishers” (Federation Edition: Iwanami Shoten, Kibokaku, Dojinsha, Kobundo, Sobun Kaku) and the “bourgeois publishers” (Kaijosa) over the publication of the “Complete Works of Marx and Engels” in 1928, which was recorded as “the most tragic incident during the Yenbon Disturbance.”

--- p.184

“It didn’t matter whether the book was cheap or expensive.

I heard this story at a bookstore in Tokyo. When “Crab Processing Ship” first came out, they thought it would probably be banned, so they kept it hidden from the shelves.

The reason was that ‘such a book will definitely sell.’” As a new publishing company, Jeonkisa adopted a strategy of gaining added value through publication and illegality while making censorship, that is, confrontation with power, visible.

--- p.190

From Cope's perspective, the more than 200,000 Korean workers in mainland Japan were potential readers and an attractive "market" for supporting the Japanese Communist Party. … He didn't care whether the Korean workers could actually read Japanese or Korean sentences.

The mission of the Joseon Council, which founded “Our Comrade,” including Lee Buk-man, was to organize 200,000 Joseon workers as readers and to become a fundraising organization using the magazine’s name.

--- p.221

Sanehiko Yamamoto was also the person responsible for the 'Yenbon' boom, which was recorded in publishing history.

The 1926 "Complete Works of Modern Japanese Literature" accepted reservations for various masterpieces from the modern era at 1 yen per volume, and secured 250,000 reservations in the first round of applications.

This yen boom created a new system that became the basis for today's publishing and distribution.

It also made a profit by providing space to proletarian cultural activists.

--- p.228

In 1932, when Song Jin-woo hosted a banquet to invite Yamamoto Sanehiko, Dong-A Ilbo owner Kim Seong-su and president Song Jin-woo received advertising contracts by entertaining advertisers in Tokyo and Osaka or inviting them to Joseon to tour Mt. Geumgang.

As a result, the Dong-A Ilbo was criticized for abandoning its “criticism of the Japanese authorities” and “degrading into an organization representing the landowners and the commercial and industrial bourgeoisie.”

--- p.236

Yamamoto appeals to the young Korean youth, who were the main customers of the company's flagship product, books on "socialism," to care more about their nation and traditions than about such resistance ideas.

In the chapter “Visit to Gyeongseong [Imperial] University,” he expressed concern that “the aspirations of Korean university students” were “leaning toward philosophy and law” rather than pure literature, and said, “I hope that Korean art researchers who have studied abroad in Japan will begin by studying the language that creates national culture.”

--- p.258

Starting with the second issue of 〈Sentence〉, the ‘Frontline Literature Series’ was created and continued until just before publication was discontinued.

'Frontline Literature' published the war journals of popular Japanese writers such as Hino Ashihei and Hayashi Fumiko, translated into Korean with little editing and no relevant information.

--- p.281

Novelist Lee Tae-jun, who was the editor-in-chief of 〈Sentence〉, cooperated in the operation of the Writers' Group for the Comfort of the Imperial Nation, which was formed in March 1939.

He donated 100 yen to the Imperial Army Comfort Writers' Group to cover the cost of sending a Joseon literary envoy, and all members of the editorial staff each donated 1 yen to cover the cost of supplies for the Imperial Army.

Thus, novelist Kim Dong-in, critic Park Young-hee, and poet Lim Hak-su were dispatched as literary envoys.

--- p.286

In the magazine Samcheolli, which featured a special feature on Ewha Womans University's school life, the students chose Fumiko Hayashi and Nobuko Yoshiya, who had been dispatched to the pen unit, as their favorite authors.

By the late 1930s, a sentence appeared in the magazine Women's magazine: "Not only international students in Tokyo, but even middle school students in Korea these days do not read Korean books and do not even look at them, considering them worthless."

--- p.307

Mo Yun-suk, Jang Deok-jo, and Choi Jeong-hui are mentioned as representative female writers who cooperated in the war after the Sino-Japanese War.

This is because they actively appealed for cooperation in the war through their works and lectures.

Seven Japanese novels have been confirmed to have responded to this policy of imperialization, six of which are by Choi Jeong-hui.

--- p.316

(Korean War) On Monday, the day after the outbreak of war, orders to buy stocks poured in from the morning in Nihonbashi Kabutocho.

Compared to the total trading volume on Saturday, June 24th, when 1.03 million shares were traded, the volume on the 25th increased by 70% to 1.8 million shares.

The stocks that were most popular were the 'old military stocks' that had been hovering around the 30-40 yen range until then.

The stock price continued to soar, quadrupling over the three years until July 27, 1953, when the armistice agreement was signed.

--- p.325

Japan participated in the war by utilizing various resources of its former empire, such as the Coast Guard's "Special Minesweeping Unit" that suffered 19 casualties and ships.

For example… MacArthur sent 70,000 landing troops from Japan and attempted to land at Incheon.

Of the 47 LSTs that departed from Japan, 37 were manned by Japanese sailors.

--- p.326

On July 25, the U.S. Army expanded its reporting standards to ban articles criticizing decisions made by UN commanders.

MacArthur's headquarters had already labeled the correspondents "traitors" and accused them of "giving aid and comfort to the enemy," and as an example, expelled some correspondents from the Korean Peninsula or prohibited them from returning to the peninsula from their reporting bases in Tokyo.

--- p.332

Jang Hyuk-ju won second place in the 1932 "Reform" contest, which gave him the opportunity to become active in the Tokyo literary world.

He had been in favor of the policy of Japan-Korea integration since the publication of “An Appeal to Korean Intellectuals” (Literature and Arts, February 1939) at the start of the Sino-Japanese War.

He was in a difficult position as he was questioned by progressive intellectuals and Koreans in Japan for his cooperation in the war after Korea gained independence.

--- p.341

Kim Sa-ryang's "I Can See the Sea," which was written from the perspective of the People's Army and published in the "Central Publication" (literature special, fall 1953 issue), was translated by Kim Dal-su, who was critical of the occupation forces and the Japanese government's participation in the Korean War.

At the time, Kim Dal-su was classified as a member of the International Faction of the Japanese Communist Party, and was looked down upon not only by the Japanese Communist Party but also by the Korean Cultural Organization Association in Japan, an organization of Koreans.

The attempt to apply the concept of proletariat to Japan was made through the translation of Marx and Engels' "Communist Manifesto" [1848].

The first people to translate the Communist Manifesto into Japanese were Shusui Kotoku and Toshihiko Sakai.

--- p.29

Sakai recalls the circumstances surrounding his initial choice of 'commoner' as a translation for 'Proletarier':

“Among the translated words, the most prominent today are the words ‘gentleman’ and ‘commoner,’ whose original words are bourgeois and proletariat.

When we think of the common people's newspaper of the time, the common people's newspaper, 'Pyeongmin Shinmun', we can see that the translation word 'Pyeongmin' captures the feeling well.

However, at the time, ‘common people’ alone was not enough for me, and for this reason, in other places I also wrote ‘common people, that is, the modern working class.’”

--- p.34

This is the cover of “Diary of a Socialist Peddler” (Shinsensha, 1971), edited by Arahata Kanson. The cart being pulled by two young men is identical in form to the milk carts used during the Russo-Japanese War.

The first description of this cart can be found in the March 13, 1904, issue of the Pyeongmin Newspaper, in the column titled “News of Peddling Missionary Work.”

The two men traveled the country on foot, holding rallies and selling 'socialist literature' that they carried in a cart.

--- p.46

The peddler's travel expenses were covered by selling commoners' books purchased at half price.

In addition to selling to individual readers of the Pyeongmin Newspaper and Jikyeon and visiting socialist organizations across the country, they also recruited members of the Socialist Association by holding talks and lectures.

--- p.49

The term "common people" used by the "Pyeongmin Shinmun" and "Jikon" referred to the Japanese proletariat, especially the "comrade-reader community" of the Pyeongmin Society and the socialist movement.

This 'commoner' does not include the Baekjeong class, who were not treated as human beings even in modern Japanese society, where the emancipation edict was issued.

Socialists also criticized discrimination against the Burakumin, but called them 'new commoners' to distinguish them from the 'commoners'.

Under the same structure, the 'Joseon people' who were placed in the same position as the 'new commoners' were also never considered as such 'commoners'.

--- p.63

In the 1910s, about 20 private libraries were established across the country since the opening of Gyeongseong Library in 1909.

However, it seems that the number was not enough for the people of Bumin.

According to the results of a survey titled “What do you want in Gyeongseong?” published in the evening edition of the June 7, 1916 edition of the Gyeongseong Ilbo, the organ of the Government-General of Korea, the responses were as follows: ① a public hall (1,032 people), ② a Japanese-Korean social organization (987 people), ③ traffic restrictions to prevent congestion in Honmachi (978 people), ④ a library (962 people), ⑤ an art museum (947 people), ⑥ a theater (918 people), and ⑦ a private middle school (906 people).

--- p.71

The permission to publish Korean newspapers such as the Dong-A Ilbo and the Chosun Ilbo was met with much criticism from various quarters at the time.… However, I believed that the newspapers published by the Governor-General alone were not enough to understand the mood of the Korean people.… Even if they were somewhat opposed, I believed that if they did not fundamentally harm public order, they should be permitted, and that is why I permitted the Korean newspapers.

--- p.80

Around this time, the pages of Korean-language newspapers such as the Dong-A Ilbo and the Chosun Ilbo, which were at the forefront of the Hangul movement, were filled with advertisements for Japanese books.

Advertisements for Japanese books, which were linked to the movement to popularize the Korean language and the Japanese language, coexisted amicably in the same space and gained influence.

--- p.82

After World War I, the Keijo Imperial University Library used German reparations to collect materials and research papers from China and various European countries, and even transferred the collection of the Kyujanggak, the royal library of Joseon, which had been under the jurisdiction of the Government-General since 1910.… Keijo Imperial University’s collection… rapidly increased to 350,000 volumes in 1932.

This was more than the combined collection of books from all public and private vocational schools in Joseon.

In 1938… it ranked 5th in terms of the number of books in the entire Japanese Empire.

--- p.86

If you look at Korean newspapers from the 1920s, you can see many advertisements for Japanese-language exam preparation books and study guides.

As previously mentioned, this was because there were not enough schools that allowed Koreans to enroll while the educational fervor was boiling.

Among the advertisements in the Dong-A Ilbo, the top seven were occupied by the Waseda University Seven Lectures series, which emphasized the possibility of self-study of middle school courses.

--- p.91

Let’s read the article titled “3,000 Books Burned to Smoke on the Bank of the Taedong River” published in the August 15, 1933 edition of the Dong-A Ilbo.

“…Book burning is not something that can only be seen in ancient times, such as during the Qin Shi Huang era or in faraway Germany. It is said that in a few days, 3,000 books will turn into smoke along the Taedong River in Pyongyang.

These are the things that have been confiscated from Pyongyang so far… Among them, most of them are social science books that are difficult to obtain, including the problematic books “The Trial” and “The Last Day” published by the Japanese Lighthouse Company, and it is said that there are also “erotic” books that will make you lose your mind.

--- p.95

The word 'Seonin' was a new word (in Japanese) created by the ruling policy of the Government-General after the annexation of Korea.

The notation of the 'Korea-Japan Annexation Treaty' promulgated on August 29, 1910 was unified as 'Korea' and 'Koreans'.

However, on the same day, by royal decree, 'the name of Korea was changed and from now on it would be called Joseon.'

Thus, first of all, the use of the words ‘Daehan’ and ‘Emperor’ was prohibited in all official documents and place names.… Books with the word ‘Daehan’ in their titles were confiscated and some of them were burned.

--- p.107

According to Imamura Tomoe, the term 'Bulyeongseonin' is a coined word of the Police Affairs Bureau of the Government-General of Korea.… If you search for 'Bulyeongseonin' in the 'Korean History Database' and the 'Korean History Information Integration System', you will see that it was used as a term to map people who participated in the anti-Japanese movement in Japanese official documents.… You can see that the use of the term 'Bulyeongseonin' gradually increased from around 1910.

--- p.113

In the case of (underground) 'newspapers', there are more than 30 published between March and July 1919.

Including those published overseas, there are over 60. The underground media outlet <Independence Newspaper>, which was published during the March 1st Independence Movement, became a source of information for the people, no less than the Declaration of Independence, with over 10,000 copies distributed in Seoul on March 1st alone.

--- p.125

The January 1, 1923 edition of the Chosun Ilbo mentions Japanese books as symbolizing the reading trend that reached a major turning point in 1922.

Here, “Marx’s ‘Economics,’ ‘Liberation,’ and ‘Reformation’ were covered, and they sold out like hotcakes as soon as they were published… There were more cases where they sold out or went out of print.”

--- p.133

Half a year before the Great Kanto Earthquake, Fumiko Kaneko and Park Yeol confessed that misunderstandings about the "Bulyeongseonin" were serious.

They worried about “what will become of the world in the future?”

The massacre of Koreans during the Great Kanto Earthquake was not an accident.

In the end, “Hyunsaehoe” was also discontinued after being published twice, and that was the last time that Kaneko and Park Yeol jointly published a media.

However, the 'Bulyeongseonin' did not disappear.

--- p.142

The opening of the era of Korean language media was accompanied by the reorganization and strengthening of censorship by the Japanese Government-General of Korea.

… However… this should not be thought of as a stereotypical equation of ‘seizure = oppression = resistance (anti-Japanese)’.

In the first place, the Chosun Ilbo was created by the Taisho Society, a representative pro-Japanese organization.

However, since then, the Dong-A Ilbo has been subjected to 30 seizures, 23 arrests, and two long-term suspensions.

Existing studies rely solely on these numbers to highlight the damage done to the Chosun Ilbo and miss the nature of the media itself.

--- p.160

The publication policy of the Government-General of Korea was centered on publication and confiscation in the 1910s, and censorship in the 1920s.

To counter this, Korean literature was published in newspapers, magazines, and books in the United States, China, Manchuria, Russia, and other countries.… The Japanese mainland became a factory where the “uncivilized” people produced “subversive” Korean media.

The majority of publications were about socialism.

--- p.164

In 1925, the Japan Proletarian Cultural League was formed.

From this period until the collapse of the Japan Proletarian Cultural Federation in 1934, the heyday of the Japanese proletarian cultural movement was upon us.

A representative magazine of this period is “Jeongi War Flag.”

--- p.180

The main competitors of the 'leftist publishers' who must aim for the pocket money of 'innocent students' are 'bourgeois' publishers such as Gaejosa and Joongangongron, which are busy commercializing 'socialism'.

For example, the fierce competition between the “left-wing publishers” (Federation Edition: Iwanami Shoten, Kibokaku, Dojinsha, Kobundo, Sobun Kaku) and the “bourgeois publishers” (Kaijosa) over the publication of the “Complete Works of Marx and Engels” in 1928, which was recorded as “the most tragic incident during the Yenbon Disturbance.”

--- p.184

“It didn’t matter whether the book was cheap or expensive.

I heard this story at a bookstore in Tokyo. When “Crab Processing Ship” first came out, they thought it would probably be banned, so they kept it hidden from the shelves.

The reason was that ‘such a book will definitely sell.’” As a new publishing company, Jeonkisa adopted a strategy of gaining added value through publication and illegality while making censorship, that is, confrontation with power, visible.

--- p.190

From Cope's perspective, the more than 200,000 Korean workers in mainland Japan were potential readers and an attractive "market" for supporting the Japanese Communist Party. … He didn't care whether the Korean workers could actually read Japanese or Korean sentences.

The mission of the Joseon Council, which founded “Our Comrade,” including Lee Buk-man, was to organize 200,000 Joseon workers as readers and to become a fundraising organization using the magazine’s name.

--- p.221

Sanehiko Yamamoto was also the person responsible for the 'Yenbon' boom, which was recorded in publishing history.

The 1926 "Complete Works of Modern Japanese Literature" accepted reservations for various masterpieces from the modern era at 1 yen per volume, and secured 250,000 reservations in the first round of applications.

This yen boom created a new system that became the basis for today's publishing and distribution.

It also made a profit by providing space to proletarian cultural activists.

--- p.228

In 1932, when Song Jin-woo hosted a banquet to invite Yamamoto Sanehiko, Dong-A Ilbo owner Kim Seong-su and president Song Jin-woo received advertising contracts by entertaining advertisers in Tokyo and Osaka or inviting them to Joseon to tour Mt. Geumgang.

As a result, the Dong-A Ilbo was criticized for abandoning its “criticism of the Japanese authorities” and “degrading into an organization representing the landowners and the commercial and industrial bourgeoisie.”

--- p.236

Yamamoto appeals to the young Korean youth, who were the main customers of the company's flagship product, books on "socialism," to care more about their nation and traditions than about such resistance ideas.

In the chapter “Visit to Gyeongseong [Imperial] University,” he expressed concern that “the aspirations of Korean university students” were “leaning toward philosophy and law” rather than pure literature, and said, “I hope that Korean art researchers who have studied abroad in Japan will begin by studying the language that creates national culture.”

--- p.258

Starting with the second issue of 〈Sentence〉, the ‘Frontline Literature Series’ was created and continued until just before publication was discontinued.

'Frontline Literature' published the war journals of popular Japanese writers such as Hino Ashihei and Hayashi Fumiko, translated into Korean with little editing and no relevant information.

--- p.281

Novelist Lee Tae-jun, who was the editor-in-chief of 〈Sentence〉, cooperated in the operation of the Writers' Group for the Comfort of the Imperial Nation, which was formed in March 1939.

He donated 100 yen to the Imperial Army Comfort Writers' Group to cover the cost of sending a Joseon literary envoy, and all members of the editorial staff each donated 1 yen to cover the cost of supplies for the Imperial Army.

Thus, novelist Kim Dong-in, critic Park Young-hee, and poet Lim Hak-su were dispatched as literary envoys.

--- p.286

In the magazine Samcheolli, which featured a special feature on Ewha Womans University's school life, the students chose Fumiko Hayashi and Nobuko Yoshiya, who had been dispatched to the pen unit, as their favorite authors.

By the late 1930s, a sentence appeared in the magazine Women's magazine: "Not only international students in Tokyo, but even middle school students in Korea these days do not read Korean books and do not even look at them, considering them worthless."

--- p.307

Mo Yun-suk, Jang Deok-jo, and Choi Jeong-hui are mentioned as representative female writers who cooperated in the war after the Sino-Japanese War.

This is because they actively appealed for cooperation in the war through their works and lectures.

Seven Japanese novels have been confirmed to have responded to this policy of imperialization, six of which are by Choi Jeong-hui.

--- p.316

(Korean War) On Monday, the day after the outbreak of war, orders to buy stocks poured in from the morning in Nihonbashi Kabutocho.

Compared to the total trading volume on Saturday, June 24th, when 1.03 million shares were traded, the volume on the 25th increased by 70% to 1.8 million shares.

The stocks that were most popular were the 'old military stocks' that had been hovering around the 30-40 yen range until then.

The stock price continued to soar, quadrupling over the three years until July 27, 1953, when the armistice agreement was signed.

--- p.325

Japan participated in the war by utilizing various resources of its former empire, such as the Coast Guard's "Special Minesweeping Unit" that suffered 19 casualties and ships.

For example… MacArthur sent 70,000 landing troops from Japan and attempted to land at Incheon.

Of the 47 LSTs that departed from Japan, 37 were manned by Japanese sailors.

--- p.326

On July 25, the U.S. Army expanded its reporting standards to ban articles criticizing decisions made by UN commanders.

MacArthur's headquarters had already labeled the correspondents "traitors" and accused them of "giving aid and comfort to the enemy," and as an example, expelled some correspondents from the Korean Peninsula or prohibited them from returning to the peninsula from their reporting bases in Tokyo.

--- p.332

Jang Hyuk-ju won second place in the 1932 "Reform" contest, which gave him the opportunity to become active in the Tokyo literary world.

He had been in favor of the policy of Japan-Korea integration since the publication of “An Appeal to Korean Intellectuals” (Literature and Arts, February 1939) at the start of the Sino-Japanese War.

He was in a difficult position as he was questioned by progressive intellectuals and Koreans in Japan for his cooperation in the war after Korea gained independence.

--- p.341

Kim Sa-ryang's "I Can See the Sea," which was written from the perspective of the People's Army and published in the "Central Publication" (literature special, fall 1953 issue), was translated by Kim Dal-su, who was critical of the occupation forces and the Japanese government's participation in the Korean War.

At the time, Kim Dal-su was classified as a member of the International Faction of the Japanese Communist Party, and was looked down upon not only by the Japanese Communist Party but also by the Korean Cultural Organization Association in Japan, an organization of Koreans.

--- p.347

Publisher's Review

Publishing culture: the key to understanding the modern and contemporary history of the empire

According to the author, who has been reading and researching the memoirs, diaries, and management materials of executives and editors of publishing and newspaper companies from 1900 to the present, magazine and publishing planners, past and present, are quite sensitive to changes in the times.

Many people treat publishing media as a declining industry, but in the past, when there were few other entertainment options, reading books was an important hobby regardless of generation, gender, class, or ethnicity.

Therefore, the author believes that there is no better material than publishing culture for understanding the modern and contemporary history of the empire.

It meticulously depicts the reasons why the Japanese Empire sent literary novelists like Hayashi Fumiko to the battlefield to write war reports for war propaganda, and mobilized the presidents of Kodansha and Asahi Shimbun to the war departments for external propaganda.

In addition, the relationship between Hayashi Fumiko and novelist Choi Jeong-hee, and the entertainment provided by Dong-A Ilbo executives to Yamamoto Sanehiko, editor of the representative Japanese magazine “Kaizō” in the 1930s, were also brought into view.

'Unsung' Books That Survived Despite Severe Censorship

The author's central argument throughout this book is that even strong censorship could not kill publishing culture.

The Japanese Empire had a publication police under the Ministry of Home Affairs, and ideological inspectors were also active.

The author noted that even when such sales bans were issued, there were publishing movements that distributed and generated profits through 'preaching' using carts to avoid surveillance.

In addition, we delve into how the legal and illegal publishing capital of the Japanese Empire interacted with the publishing market of colonial Korea.

For example, there was a time when the more the political power of the Japanese Empire strengthened its suppression of socialism, the more readers desired socialist books.

I tried to argue that imperial oppression became the driving force behind capital production, and from that point I hoped to find hints for living today.

The explanation of the role of Japanese is also notable.

Although it was a language imposed by the invaders, it was Japanese books that provided the necessary knowledge to those who dreamed of resistance in a reality where censorship of Korean literature was relatively strong.

It also shows that Japanese books were very close to those who enjoyed reading and those who dreamed of success in the colony.

From the Russo-Japanese War to the Japanese-Korean War

This book consists of eight chapters.

In Chapter 1, “Proletariat,” the process of selecting “common people” as a translation of proletariat in the first Japanese translation of the “Communist Manifesto,” published after the Russo-Japanese War, and the process of colonization of Korea were discussed.

Chapter 2, “Library,” focuses on Joseon’s libraries as imperial archives and argues about what words and people they included and excluded.

Chapter 3, “The Unruly People,” and Chapter 4, “Censorship,” discuss the tactics employed by Korean socialists to publish books in mainland Japan, have them censored by the Ministry of Home Affairs’ Library Division, and then bring them back to the Korean Peninsula.

It is also noteworthy that the parties who created the 'unruly' Korean media demanded 'naeyeol (prior coordination)' from the Ministry of Home Affairs.

They attempted to secure the possibility of media distribution in exchange for providing their information to the authorities in advance.

This was a very risky and precarious negotiation.

Chapters 5, “Capital,” and 6, “Colony,” reveal that media capital in mainland Japan and Korea has been restructuring the reading environment and market, reaping profits through the seeds of “unruliness.”

Chapter 7, “Translation,” focuses on the cultural phenomenon that occurred as media control during the Second Sino-Japanese War linked the reproduction of hierarchical relationships in Tokyo, the center of the empire, and colonial Korea.

Chapter 8, “War,” analyzes the Japanese media’s coverage of the Korean War, which concealed the reality of the revival of the intellectual system and economic power of the former Japanese Empire (participation in the Korean War), while striving to portray Japan as a “neutral, peaceful nation” that did not engage in violence.

"The Books We Absolutely Recommend Right Now," Picked by Japanese Experts

Despite being a book written in Japanese and aimed at a Japanese audience and featuring colonialism at the forefront, this book received an unusually large amount of attention from the Japanese media.

The book was reviewed by the Mainichi Shimbun, the Nihon Keizai Shimbun, and Kyodo News (reprinted in 23 local newspapers), and was selected as a representative book of the first half of 2024 in a survey conducted by specialized book review newspapers such as the Book Newspaper and the Weekly Reader.

Reviews such as “This book sharply depicts the complex negotiations and conflicts between the ‘mainland’ and the colony while examining the publishing and distribution of colonial Korea… A good book that reinterprets modern history in a transnational way” (Professor Yoshiaki Fukuma, Kyoto University), “A research book that encompasses multiple fields such as the history of literature, cultural history, history of ideas, history of media, and history of social movements” (Professor Noritsugu Komibuchi, Waseda University), and “45 experts on Korea and books selected it as a ‘book they absolutely want to recommend right now’” (Professor Rie Matsui, Atomi Gakuin University) clearly demonstrate the value of this book.

According to the author, who has been reading and researching the memoirs, diaries, and management materials of executives and editors of publishing and newspaper companies from 1900 to the present, magazine and publishing planners, past and present, are quite sensitive to changes in the times.

Many people treat publishing media as a declining industry, but in the past, when there were few other entertainment options, reading books was an important hobby regardless of generation, gender, class, or ethnicity.

Therefore, the author believes that there is no better material than publishing culture for understanding the modern and contemporary history of the empire.

It meticulously depicts the reasons why the Japanese Empire sent literary novelists like Hayashi Fumiko to the battlefield to write war reports for war propaganda, and mobilized the presidents of Kodansha and Asahi Shimbun to the war departments for external propaganda.

In addition, the relationship between Hayashi Fumiko and novelist Choi Jeong-hee, and the entertainment provided by Dong-A Ilbo executives to Yamamoto Sanehiko, editor of the representative Japanese magazine “Kaizō” in the 1930s, were also brought into view.

'Unsung' Books That Survived Despite Severe Censorship

The author's central argument throughout this book is that even strong censorship could not kill publishing culture.

The Japanese Empire had a publication police under the Ministry of Home Affairs, and ideological inspectors were also active.

The author noted that even when such sales bans were issued, there were publishing movements that distributed and generated profits through 'preaching' using carts to avoid surveillance.

In addition, we delve into how the legal and illegal publishing capital of the Japanese Empire interacted with the publishing market of colonial Korea.

For example, there was a time when the more the political power of the Japanese Empire strengthened its suppression of socialism, the more readers desired socialist books.

I tried to argue that imperial oppression became the driving force behind capital production, and from that point I hoped to find hints for living today.

The explanation of the role of Japanese is also notable.

Although it was a language imposed by the invaders, it was Japanese books that provided the necessary knowledge to those who dreamed of resistance in a reality where censorship of Korean literature was relatively strong.

It also shows that Japanese books were very close to those who enjoyed reading and those who dreamed of success in the colony.

From the Russo-Japanese War to the Japanese-Korean War

This book consists of eight chapters.

In Chapter 1, “Proletariat,” the process of selecting “common people” as a translation of proletariat in the first Japanese translation of the “Communist Manifesto,” published after the Russo-Japanese War, and the process of colonization of Korea were discussed.

Chapter 2, “Library,” focuses on Joseon’s libraries as imperial archives and argues about what words and people they included and excluded.

Chapter 3, “The Unruly People,” and Chapter 4, “Censorship,” discuss the tactics employed by Korean socialists to publish books in mainland Japan, have them censored by the Ministry of Home Affairs’ Library Division, and then bring them back to the Korean Peninsula.

It is also noteworthy that the parties who created the 'unruly' Korean media demanded 'naeyeol (prior coordination)' from the Ministry of Home Affairs.

They attempted to secure the possibility of media distribution in exchange for providing their information to the authorities in advance.

This was a very risky and precarious negotiation.

Chapters 5, “Capital,” and 6, “Colony,” reveal that media capital in mainland Japan and Korea has been restructuring the reading environment and market, reaping profits through the seeds of “unruliness.”

Chapter 7, “Translation,” focuses on the cultural phenomenon that occurred as media control during the Second Sino-Japanese War linked the reproduction of hierarchical relationships in Tokyo, the center of the empire, and colonial Korea.

Chapter 8, “War,” analyzes the Japanese media’s coverage of the Korean War, which concealed the reality of the revival of the intellectual system and economic power of the former Japanese Empire (participation in the Korean War), while striving to portray Japan as a “neutral, peaceful nation” that did not engage in violence.

"The Books We Absolutely Recommend Right Now," Picked by Japanese Experts

Despite being a book written in Japanese and aimed at a Japanese audience and featuring colonialism at the forefront, this book received an unusually large amount of attention from the Japanese media.

The book was reviewed by the Mainichi Shimbun, the Nihon Keizai Shimbun, and Kyodo News (reprinted in 23 local newspapers), and was selected as a representative book of the first half of 2024 in a survey conducted by specialized book review newspapers such as the Book Newspaper and the Weekly Reader.

Reviews such as “This book sharply depicts the complex negotiations and conflicts between the ‘mainland’ and the colony while examining the publishing and distribution of colonial Korea… A good book that reinterprets modern history in a transnational way” (Professor Yoshiaki Fukuma, Kyoto University), “A research book that encompasses multiple fields such as the history of literature, cultural history, history of ideas, history of media, and history of social movements” (Professor Noritsugu Komibuchi, Waseda University), and “45 experts on Korea and books selected it as a ‘book they absolutely want to recommend right now’” (Professor Rie Matsui, Atomi Gakuin University) clearly demonstrate the value of this book.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: June 15, 2025

- Page count, weight, size: 418 pages | 616g | 152*224*21mm

- ISBN13: 9791156122968

- ISBN10: 1156122961

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)