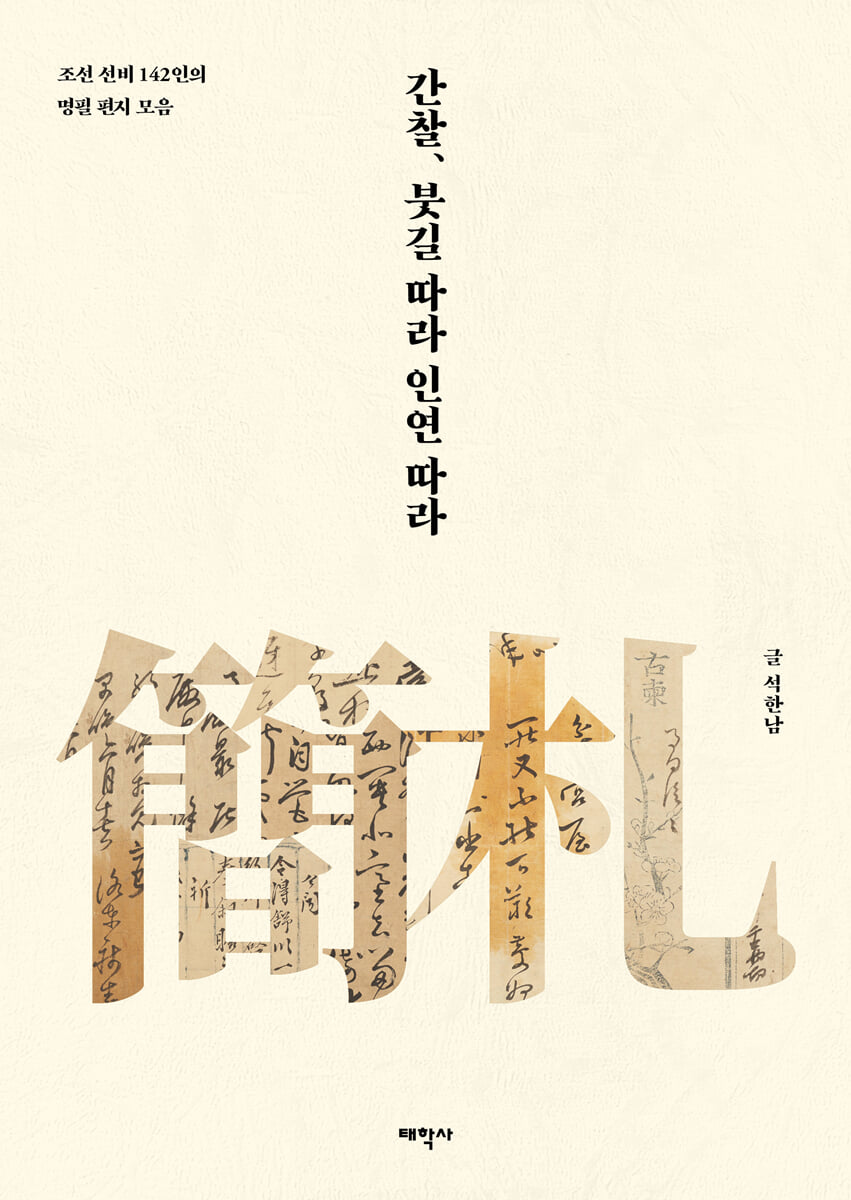

Follow the path of the brush and the fate

|

Description

Book Introduction

Revealed for the first time,

The stories of 142 famous calligraphers from the Joseon Dynasty and their writings.

From Il-du Jeong Yeo-chang, a master of Neo-Confucianism during the reign of King Seongjong of Joseon, to Sim-am Jo Du-sun, who served as Prime Minister and Chief of the Gyeongbokgung Yeonggeondogam during the reign of King Gojong, the opinions of 142 renowned scholars and Confucian scholars of the Joseon Dynasty were gathered in one place.

The main characters who wrote these letters were the prominent Confucian scholars who influenced their times, such as Jo Gwang-jo, Yi Hwang, Kim Jang-saeng, Yi Hang-bok, Kim Sang-heon, Jo Gyeong, Heo Mok, Song Si-yeol, Nam Gu-man, Kwon Sang-ha, and Kim Chang-hyeop. These letters will be a valuable resource for studying the microhistory of the Joseon Dynasty, and their handwriting, each with its own unique style, is also a valuable resource that will help study Joseon Dynasty calligraphy.

Seok Han-nam, a researcher of ancient documents and the author of this book who translated and wrote it, said, “Old letters are generally called ‘Ganchal (簡札)’.

“Its name comes from the fact that in the days before paper, people used to write on bamboo or pieces of wood to communicate,” he said, adding, “Ganchal clearly shows the inner workings of the Joseon scholars’ mental world and lifestyle.

He explains its significance by saying, “It also provides a valuable opportunity to glimpse the handwriting of our ancestors.”

The observations included in this book are precious relics owned by Chairman Lee Sang-jun of The Prima Co., Ltd., a famous collector known to everyone in the Korean art world.

This book is a reorganization of 164 short notes and poems by 142 authors, arranged in chronological order of their birth and death, from the six volumes of Ganchalcheop, one of his numerous collections of famous calligraphers from the Joseon Dynasty. This publication marks the first time that these notes have been made public.

The author introduces the author of each commentary and explains that he or she transcribed the original text of the commentary and translated and annotated it. This is a very rare case in which an individual, rather than a government agency, transcribed and annotated a handwritten commentary written in cursive script rather than a printed anthology.

The stories of 142 famous calligraphers from the Joseon Dynasty and their writings.

From Il-du Jeong Yeo-chang, a master of Neo-Confucianism during the reign of King Seongjong of Joseon, to Sim-am Jo Du-sun, who served as Prime Minister and Chief of the Gyeongbokgung Yeonggeondogam during the reign of King Gojong, the opinions of 142 renowned scholars and Confucian scholars of the Joseon Dynasty were gathered in one place.

The main characters who wrote these letters were the prominent Confucian scholars who influenced their times, such as Jo Gwang-jo, Yi Hwang, Kim Jang-saeng, Yi Hang-bok, Kim Sang-heon, Jo Gyeong, Heo Mok, Song Si-yeol, Nam Gu-man, Kwon Sang-ha, and Kim Chang-hyeop. These letters will be a valuable resource for studying the microhistory of the Joseon Dynasty, and their handwriting, each with its own unique style, is also a valuable resource that will help study Joseon Dynasty calligraphy.

Seok Han-nam, a researcher of ancient documents and the author of this book who translated and wrote it, said, “Old letters are generally called ‘Ganchal (簡札)’.

“Its name comes from the fact that in the days before paper, people used to write on bamboo or pieces of wood to communicate,” he said, adding, “Ganchal clearly shows the inner workings of the Joseon scholars’ mental world and lifestyle.

He explains its significance by saying, “It also provides a valuable opportunity to glimpse the handwriting of our ancestors.”

The observations included in this book are precious relics owned by Chairman Lee Sang-jun of The Prima Co., Ltd., a famous collector known to everyone in the Korean art world.

This book is a reorganization of 164 short notes and poems by 142 authors, arranged in chronological order of their birth and death, from the six volumes of Ganchalcheop, one of his numerous collections of famous calligraphers from the Joseon Dynasty. This publication marks the first time that these notes have been made public.

The author introduces the author of each commentary and explains that he or she transcribed the original text of the commentary and translated and annotated it. This is a very rare case in which an individual, rather than a government agency, transcribed and annotated a handwritten commentary written in cursive script rather than a printed anthology.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

prolog

Part 1: Jeong Yeo-chang - Kim Jang-saeng

Observations of people born in the late 1400s to early 1500s

001 Jeong Yeo-chang

002 Jo Gwang-jo

003 Lee Eon-jeok

004 Seongsu Chim

005 Yi Hwang

006 Geum Nan-su

007 Kim Bu-ryun

008 Kim Hyun-seong

009 Lee Won-ik

010 Kim Jang-saeng

Part 2: Song Sang-hyeon - Chae Yu-hu

Observations of people born in the late 1500s

011 Jeon (傳) Song Sang-hyeon (宋象賢)

012 Lee Hang-bok

013 Han Jun-gyeom

014 Jeon (傳) Kim Ji-nam (金止男)

015 Lee Jun

016 Kim Sang-jun (金尙寯)

017 Lee Hong-ju

018 Park Dong-seon

019 Lee Jeong-gu

020 Seong Gye-seon

021 Park Dong-ryang

022 Simyeol (沈悅)

023 Kim Sang-heon

024 Kim Ryu (金?)

025 Kihyeop (Strange Association)

026 Lee Hyeon-yeong

027 Jo Ik

028 Kim Yuk (金堉)

029 Lee Si-baek

030 Jeong Hong-myeong

031 Yoon Shin-ji

032 Lee Sik

033 Kang Hak-nyeon

034 Lee Gyeong-yeo

035 Shim Dae-bu

036 Jo Kyung

037 Jang Yu (張維)

038 Oh Jun (吳竣)

039 Shin Ik-seong

040 Lee?

041 Kim Se-ryeom

042 Lee Si-bang

043 Lee Won-jin

044 Lee Myeong-han

045 Jo Sok

046 Lee Gyeong-seok

047 Heo Mok (許穆)

048 Park Jeong (朴炡)

049 Kim Nam-jung

050 Lee So-han

051 Chae Yu-hu

Part 3: Park Ui - Kim Woo-hang

Observations of people born in the early 1600s

052 Park Ui (Park?)

053 Im Yu-hu (任有後)

054 Lee Si-sul

055 Song Si-yeol

056 Heo Gyeok

057 Hwangho (黃?)

058 Yu Do-sam

059 Yoon Seon-geo (尹宣擧)

060 Park Jang-won

061 Lee Jeong-gi (李廷?)

062 Lee Sang-jin

063 Lee Tae-yeon

064 Lee Jeong-yeong

065 Lee Eun-sang

066 Hongwi (洪?)

067 Yeoseongje (呂聖齊)

068 Kim Su-heung (金壽興)

069 Lee Dan-sang

070 Nam Yong-ik (南龍翼)

071 Kim Su-hang

072 Nam Gu-man

073 Lee Se-hwa

074 Jeong Jae-sung

075 Hong Yu-gu (洪有龜)

076 Lee Min-seo

077 Yun Sim (尹深)

078 Kim Seok-ju (金錫胄)

079 Shin Ik-sang

080 Seo Mun-jung

081 Lee Se-baek

082 Yoon Ji-wan

083 Nayangjwa

084 Jo Ji-gyeom

085 Zhao Weiming

086 Jo Sang-woo

087 Sim Ik-hyeon (沈益顯)

088 Kwon Sang-ha

089 Lee Don (Lee?)

090 Lee Se-pil

091 Shim Kwon

092 Oh Do-il

093 Lee Yu

094 Shin Wan

095 Choi Seok-jeong (崔錫鼎)

096 Park Tae-yu

097 Lee Se-jae

098 Lee Jeong-gyeom

099 Jeong Jae-ryun

100 Kim Gu (金構)

101 Kim Woo-hang

Part 4: Kang Hyeon - Won Gyeong-ha

Observations of people born in the late 1600s

102 Kang Hyeon (姜?)

103 Choi Gyu-seo

104 Kim Chang-hyeop

105 Song Jing-eun (宋徵殷)

106 Lee Ik-su

107 Kim Chang-heup (金昌翕)

108 Park Tae-bo

109 Lee Hee-jo (李喜朝)

110 Lee In-yeop

111 Song Sang-gi

112 Kim Jin-gyu (金鎭圭)

113 Yoon Deok-jun

114 Kim Chang-eop

115 Min Jin-hu

116 Oh Tae-ju

117 Choi Chang-dae

118 Cai Pengyun

119 Lee Byeong-yeon

120 Hanji (韓祉)

121 Yoon Soon (尹淳)

122 Lee Jae (李縡)

123 Kim Jae-ro

124 An Jung-gwan

125 Yun Bong-gu (尹鳳九)

126 Yu Cheok-gi

127 Wonkyungha (元景夏)

Part 5: Kim Si-chan - Unknown

Observations of people born after 1700

128 Kim Si-chan (金時粲)

129 Jo Myeong-jeong

130 Jo Jung-hoe

131 Seo Ji-su

132 Kim Sang-suk (金相肅)

133 Hong Nak-seong

134 Kim Jong-hu

135 Min Baek-bun

136 Kim Jong-su (金鍾秀)

137 Kim Geun-sun

138 Cho Doo-soon

139 Unknown 1

140 Unknown 2

141 Unknown 3

142 Unknown 4

Epilogue - Lee Sang-jun

Part 1: Jeong Yeo-chang - Kim Jang-saeng

Observations of people born in the late 1400s to early 1500s

001 Jeong Yeo-chang

002 Jo Gwang-jo

003 Lee Eon-jeok

004 Seongsu Chim

005 Yi Hwang

006 Geum Nan-su

007 Kim Bu-ryun

008 Kim Hyun-seong

009 Lee Won-ik

010 Kim Jang-saeng

Part 2: Song Sang-hyeon - Chae Yu-hu

Observations of people born in the late 1500s

011 Jeon (傳) Song Sang-hyeon (宋象賢)

012 Lee Hang-bok

013 Han Jun-gyeom

014 Jeon (傳) Kim Ji-nam (金止男)

015 Lee Jun

016 Kim Sang-jun (金尙寯)

017 Lee Hong-ju

018 Park Dong-seon

019 Lee Jeong-gu

020 Seong Gye-seon

021 Park Dong-ryang

022 Simyeol (沈悅)

023 Kim Sang-heon

024 Kim Ryu (金?)

025 Kihyeop (Strange Association)

026 Lee Hyeon-yeong

027 Jo Ik

028 Kim Yuk (金堉)

029 Lee Si-baek

030 Jeong Hong-myeong

031 Yoon Shin-ji

032 Lee Sik

033 Kang Hak-nyeon

034 Lee Gyeong-yeo

035 Shim Dae-bu

036 Jo Kyung

037 Jang Yu (張維)

038 Oh Jun (吳竣)

039 Shin Ik-seong

040 Lee?

041 Kim Se-ryeom

042 Lee Si-bang

043 Lee Won-jin

044 Lee Myeong-han

045 Jo Sok

046 Lee Gyeong-seok

047 Heo Mok (許穆)

048 Park Jeong (朴炡)

049 Kim Nam-jung

050 Lee So-han

051 Chae Yu-hu

Part 3: Park Ui - Kim Woo-hang

Observations of people born in the early 1600s

052 Park Ui (Park?)

053 Im Yu-hu (任有後)

054 Lee Si-sul

055 Song Si-yeol

056 Heo Gyeok

057 Hwangho (黃?)

058 Yu Do-sam

059 Yoon Seon-geo (尹宣擧)

060 Park Jang-won

061 Lee Jeong-gi (李廷?)

062 Lee Sang-jin

063 Lee Tae-yeon

064 Lee Jeong-yeong

065 Lee Eun-sang

066 Hongwi (洪?)

067 Yeoseongje (呂聖齊)

068 Kim Su-heung (金壽興)

069 Lee Dan-sang

070 Nam Yong-ik (南龍翼)

071 Kim Su-hang

072 Nam Gu-man

073 Lee Se-hwa

074 Jeong Jae-sung

075 Hong Yu-gu (洪有龜)

076 Lee Min-seo

077 Yun Sim (尹深)

078 Kim Seok-ju (金錫胄)

079 Shin Ik-sang

080 Seo Mun-jung

081 Lee Se-baek

082 Yoon Ji-wan

083 Nayangjwa

084 Jo Ji-gyeom

085 Zhao Weiming

086 Jo Sang-woo

087 Sim Ik-hyeon (沈益顯)

088 Kwon Sang-ha

089 Lee Don (Lee?)

090 Lee Se-pil

091 Shim Kwon

092 Oh Do-il

093 Lee Yu

094 Shin Wan

095 Choi Seok-jeong (崔錫鼎)

096 Park Tae-yu

097 Lee Se-jae

098 Lee Jeong-gyeom

099 Jeong Jae-ryun

100 Kim Gu (金構)

101 Kim Woo-hang

Part 4: Kang Hyeon - Won Gyeong-ha

Observations of people born in the late 1600s

102 Kang Hyeon (姜?)

103 Choi Gyu-seo

104 Kim Chang-hyeop

105 Song Jing-eun (宋徵殷)

106 Lee Ik-su

107 Kim Chang-heup (金昌翕)

108 Park Tae-bo

109 Lee Hee-jo (李喜朝)

110 Lee In-yeop

111 Song Sang-gi

112 Kim Jin-gyu (金鎭圭)

113 Yoon Deok-jun

114 Kim Chang-eop

115 Min Jin-hu

116 Oh Tae-ju

117 Choi Chang-dae

118 Cai Pengyun

119 Lee Byeong-yeon

120 Hanji (韓祉)

121 Yoon Soon (尹淳)

122 Lee Jae (李縡)

123 Kim Jae-ro

124 An Jung-gwan

125 Yun Bong-gu (尹鳳九)

126 Yu Cheok-gi

127 Wonkyungha (元景夏)

Part 5: Kim Si-chan - Unknown

Observations of people born after 1700

128 Kim Si-chan (金時粲)

129 Jo Myeong-jeong

130 Jo Jung-hoe

131 Seo Ji-su

132 Kim Sang-suk (金相肅)

133 Hong Nak-seong

134 Kim Jong-hu

135 Min Baek-bun

136 Kim Jong-su (金鍾秀)

137 Kim Geun-sun

138 Cho Doo-soon

139 Unknown 1

140 Unknown 2

141 Unknown 3

142 Unknown 4

Epilogue - Lee Sang-jun

Publisher's Review

A story written along the path of the brush and according to fate

“I am barely making a living with my parents, but the bodies of those who starve to death continue to pile up, and it seems that no one will survive in the future. What more can I say?

“Every day when I sit down to eat, it feels like there’s a needle stuck in my throat.”

On February 13, 1671 (the 12th year of King Hyeonjong’s reign), Nam Gu-man wrote a letter to an elder in his family who was his uncle’s age.

Nam Gu-man is a well-known figure known for his sijo poem, “Is your classmate bright?”

From 1670, the Joseon people suffered an unprecedented famine due to abnormal weather and the spread of infectious diseases.

This disaster, which began in the year of Gyeongsul (1670) and continued until the year of Sinhae (1671), is recorded in history as the Gyeongsin Great Famine.

This great famine caused nearly a million deaths from disease and starvation throughout Joseon.

In Hamgyeong Province, the damage to the people was the greatest because swarms of locusts appeared and devoured even the relief crops.

The Hamgyeong-do governor at that time was Nam Gu-man.

“After being buried in the ground, I will never be able to see your voice or your appearance again. This body feels lonely and all things seem distant. I close the door and lie down alone, shedding tears. What more can I say to you?”

On January 12, 1701 (the 27th year of King Sukjong's reign), Kim Chang-hyeop held his only son, who was still as young as a newborn, in his heart and wrote this.

His son, Kim Sung-gyeom (金崇謙), was a prodigy who was deeply learned and left behind hundreds of poems, although he died young at the age of 19.

Meanwhile, the latter part of the notice often contains content about sending goods.

Hong Yu-gu, who was busy welcoming Chinese envoys, wrote the following on February 18, 1682 (the 8th year of King Sukjong's reign) while sending a memorial offering to the recipient.

“The small writing on the left is to be offered as an offering to the ancestral rites, but it is so insignificant that I feel ashamed and disappointed.

Two lumps of yeast

Two croakers

Early Fourth Round”

The author says that “this is a very grand gift given and received as recorded in the records,” and that most of the gifts were nothing more than fans, calendars, paper, ink, meat, and sweets.

The surveillance culture of Joseon scholars

The author says that because the letters are closely related to the private lives of scholars who lived in an era, their format and content are very diverse, and that when the recipient is an elder, the letters are written neatly in running script, which is close to regular script, but when sent to children or close subordinates, the handwriting is sometimes so cursive that it is almost impossible for a third party to read.

There were also cases where the sender omitted the name to show that he or she was very close to the recipient. When only two letters of the name would have been used, the two letters were written as "unknown" to mean "omitting the name when in a position where one knows the recipient well."

There are even cases where it is written as 'Heum (欠)', which is said to express the meaning of not using the name as an onomatopoeia like 'Heum!' or 'Ahem!'

At the end of the observations containing serious content, '병(丙)' or '정(丁)' was sometimes written. Since '병(丙)' and '정(丁)' correspond to '화(火)' in the Five Elements, it was a request to burn them after reading.

However, as these observations were surprisingly frequently discovered, it seemed that recipients were ignoring them.

“I am barely making a living with my parents, but the bodies of those who starve to death continue to pile up, and it seems that no one will survive in the future. What more can I say?

“Every day when I sit down to eat, it feels like there’s a needle stuck in my throat.”

On February 13, 1671 (the 12th year of King Hyeonjong’s reign), Nam Gu-man wrote a letter to an elder in his family who was his uncle’s age.

Nam Gu-man is a well-known figure known for his sijo poem, “Is your classmate bright?”

From 1670, the Joseon people suffered an unprecedented famine due to abnormal weather and the spread of infectious diseases.

This disaster, which began in the year of Gyeongsul (1670) and continued until the year of Sinhae (1671), is recorded in history as the Gyeongsin Great Famine.

This great famine caused nearly a million deaths from disease and starvation throughout Joseon.

In Hamgyeong Province, the damage to the people was the greatest because swarms of locusts appeared and devoured even the relief crops.

The Hamgyeong-do governor at that time was Nam Gu-man.

“After being buried in the ground, I will never be able to see your voice or your appearance again. This body feels lonely and all things seem distant. I close the door and lie down alone, shedding tears. What more can I say to you?”

On January 12, 1701 (the 27th year of King Sukjong's reign), Kim Chang-hyeop held his only son, who was still as young as a newborn, in his heart and wrote this.

His son, Kim Sung-gyeom (金崇謙), was a prodigy who was deeply learned and left behind hundreds of poems, although he died young at the age of 19.

Meanwhile, the latter part of the notice often contains content about sending goods.

Hong Yu-gu, who was busy welcoming Chinese envoys, wrote the following on February 18, 1682 (the 8th year of King Sukjong's reign) while sending a memorial offering to the recipient.

“The small writing on the left is to be offered as an offering to the ancestral rites, but it is so insignificant that I feel ashamed and disappointed.

Two lumps of yeast

Two croakers

Early Fourth Round”

The author says that “this is a very grand gift given and received as recorded in the records,” and that most of the gifts were nothing more than fans, calendars, paper, ink, meat, and sweets.

The surveillance culture of Joseon scholars

The author says that because the letters are closely related to the private lives of scholars who lived in an era, their format and content are very diverse, and that when the recipient is an elder, the letters are written neatly in running script, which is close to regular script, but when sent to children or close subordinates, the handwriting is sometimes so cursive that it is almost impossible for a third party to read.

There were also cases where the sender omitted the name to show that he or she was very close to the recipient. When only two letters of the name would have been used, the two letters were written as "unknown" to mean "omitting the name when in a position where one knows the recipient well."

There are even cases where it is written as 'Heum (欠)', which is said to express the meaning of not using the name as an onomatopoeia like 'Heum!' or 'Ahem!'

At the end of the observations containing serious content, '병(丙)' or '정(丁)' was sometimes written. Since '병(丙)' and '정(丁)' correspond to '화(火)' in the Five Elements, it was a request to burn them after reading.

However, as these observations were surprisingly frequently discovered, it seemed that recipients were ignoring them.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: June 5, 2025

- Page count, weight, size: 512 pages | 176*248*35mm

- ISBN13: 9791168103603

- ISBN10: 1168103606

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)