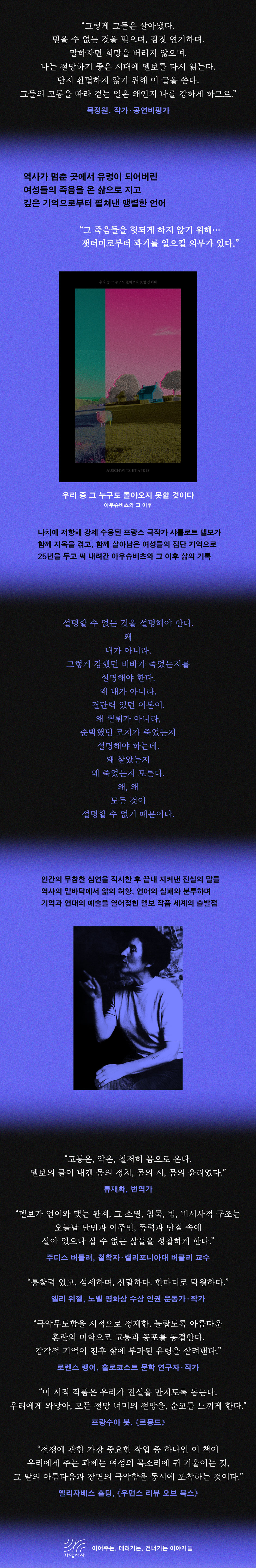

None of us will come back

|

Description

Book Introduction

None of Us Will Return: Auschwitz and After is a memoir by French playwright Charlotte Delvaux, who was arrested for anti-Nazi activities during World War II and imprisoned in the death camp Auschwitz.

The hellish experience and the subsequent lives of the female resistance fighters who participated are described in an experimental format.

There were 230 French women on the train to Auschwitz that Delvaux was on, and only 49 of them returned alive after the war.

After his return in 1945, he wrote a three-volume series, "Auschwitz and After," spanning 25 years, encompassing his own memories and the testimonies of survivors.

This memoir, which reveals the truth about Auschwitz through the collective memory of women, became the foundation for Delvaux's work, which focused on the issues of existence, knowledge, and language throughout her life.

It has been praised for creating a place for women in a history written in capital letters by state power and male voices, and its philosophical and political values have been consistently reinterpreted across time.

In the Korean edition, the three books that were originally separate volumes were combined, and the title of Part 1, "None of Us Will Return," was used as the title of the entire book.

The hellish experience and the subsequent lives of the female resistance fighters who participated are described in an experimental format.

There were 230 French women on the train to Auschwitz that Delvaux was on, and only 49 of them returned alive after the war.

After his return in 1945, he wrote a three-volume series, "Auschwitz and After," spanning 25 years, encompassing his own memories and the testimonies of survivors.

This memoir, which reveals the truth about Auschwitz through the collective memory of women, became the foundation for Delvaux's work, which focused on the issues of existence, knowledge, and language throughout her life.

It has been praised for creating a place for women in a history written in capital letters by state power and male voices, and its philosophical and political values have been consistently reinterpreted across time.

In the Korean edition, the three books that were originally separate volumes were combined, and the title of Part 1, "None of Us Will Return," was used as the title of the entire book.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Recommendation_That's how they survived, believing in the unbelievable (Mok Jeong-won)

Ⅰ.

None of us will come back

Ⅱ.

Useless knowledge

Ⅲ.

The measure of our days

Translator's Note: The Politics of the Body, the Poetry of the Body, the Ethics of the Body

A Recommendation_The World of Charlotte Delbor: Where the Art of True Memory and Solidarity Began

Ⅰ.

None of us will come back

Ⅱ.

Useless knowledge

Ⅲ.

The measure of our days

Translator's Note: The Politics of the Body, the Poetry of the Body, the Ethics of the Body

A Recommendation_The World of Charlotte Delbor: Where the Art of True Memory and Solidarity Began

Detailed image

Into the book

“Look at that, look at that.” At first, you doubt what you saw.

It is clearly distinguished from white snow.

It's in the middle of the yard.

Naked bodies.

They are lined up facing each other.

It's brand new.

It is a white color with a slightly bluish tint that is located above the eyes.

The head was completely shaved, and the hair on the pubic area stood up stiffly.

The corpses are frozen.

White, but the nails are brown.

The toes pointing up are a bit funny.

So absurd and horrific.

(...)

Now the mannequins are lying in the snow.

Soaked in the winter sun.

This sunlight reminds me of the sun on asphalt.

The mannequins lying in the snow are yesterday's classmates.

They were there yesterday, during roll call.

They stood in groups of five on either side of Lagerstrasse.

They set off for the workshop and headed towards the wetlands.

Yesterday they were hungry.

I scratched my body because I had teeth.

Yesterday they drank dirty soup.

They had diarrhea and were beaten.

Yesterday they were in pain.

Yesterday they wished to die.

Now they are here, naked corpses in the snow.

They are dead in block 25.

Death in Block 25 has neither the quiet nor the peace that is usually expected from death.

---From "Mannequin"

The eyes flash like sparks in the refracted light.

There is no spreading light, only the hard, cold light of ice.

Everything is carved with sharp outlines, as if it were cut off.

The sky is blue, solid, and frozen.

Plants trapped in glaciers come to mind.

This is something that could only happen in the Arctic, where glaciers freeze even underwater plants.

We are trapped in a block of ice like those plants.

In the ice, which is hard, sharp as if cut, and transparent, almost like crystal.

And light penetrates this crystal.

As if the light were frozen in the ice, or as if the ice itself were light.

It was only after a while that we realized that we could still move through this iceberg.

We wiggle our toes in our shoes and roll our feet on the floor.

Fifteen thousand women are stamping their feet, but there is no sound.

We are in an environment where time has been wasted.

In this ice, in this light, in these blindingly dazzling eyes, we cannot even tell whether we are there or not, this ice, this light, this silence.

---From "The Next Day"

I am again overcome with despair.

“How are we going to get out of here?”

Lully looks at me.

Smile at me.

Her hand touches mine gently, trying to comfort me.

And I repeat to her:

Please let her know that this is all for nothing.

“I clearly told you.

I can't do it today.

This time it's real."

Lully looks around us.

After making sure that no Capo is nearby, he grabs my wrist and says:

“Come behind me so I can’t see you.

“You can cry now,” she says shyly, in a low voice.

I'm sure he said this because he needed to hear it from me.

That's understandable, because if it's such kind encouragement, I'll follow it without hesitation.

I set my extension on the floor, lean on the handle, and cry.

I didn't want to cry.

But tears leak out and flow down my cheeks.

I let the tears flow.

And when a teardrop wets my lips, I feel a salty taste.

I keep crying.

Lully sees the net while working.

Every now and then she turns her body back and gently wipes my face with her sleeve.

I cry.

I don't think about anything anymore.

I cry.

When Lully pulled me, I no longer knew why I was crying.

“It’s done now.

Okay, let's get to work.

“Look, it’s okay now.” I wasn’t ashamed at all that I cried at such kind words.

It felt like I was crying in my mother's arms.

---From "Ryulyu"

You would have thought that only solemn words would come from the lips of the dying.

(...) Almost all of our comrades, lying naked on the shabby stretcher, said this.

“This time I’m going to die.”

They were naked on bare planks.

They were dirty, and the planks were dirty with diarrhea and lice.

They probably didn't know how hard this was.

The survivors are supposed to convey their last words to their parents.

Parents must have expected something grand.

I can't let them down.

Vulgar language would never be appropriate in an anthology of last words.

But I couldn't allow myself to become weak.

So they said this.

“This time, I’m going to die.” That was so as not to take away the courage of others.

They didn't leave anything that could be a message, because they thought not a single one would survive.

---From "You must have thought so"

At first, we wanted to sing.

You can't even imagine.

How my heart was torn to pieces by those frail voices repeating words that were now inconceivable, words that were shattered and weak in the swamp.

The dead do not sing.

...they started acting as soon as they came back to life.

(...)

It was amazing.

Some lines from Molière that were still fresh in our memories came rushing back.

He was brought back to life completely by some inexplicable magical power.

It was amazing.

Because everyone acted with sincerity, without trying to stand out, and with humility.

The miracle of actors without vanity.

A miracle for the audience, who suddenly regain their childhood innocence and revive their imagination.

It was amazing.

Because during those two hours, even as the smoke of human flesh billowed from the chimney, we believed more in the world we were acting in.

That belief was stronger than the belief in freedom, the only freedom we believed in at the time, the very freedom for which we had to fight for another 500 days.

---From "At first, I wanted to sing"

Each person took their own memories with them.

All that weight of memory, all that weight of the past.

When I arrived, I had to put all that weight down.

I had to take everything off and go in.

One might say that even if everything is taken away from a human, memories are the only exception.

But that's something you say without knowing anything.

Once you remove the attributes of human existence from a human being, their memories also disappear.

Memories fall off piece by piece, like burnt skin.

You will never understand how it is possible to survive so naked.

This is what I can't explain to you.

In the end, a few people survived like that.

People call things that cannot be explained a miracle.

The survivors had to regain their memories.

He had to get back what he once owned.

His knowledge, his experience, his childhood memories, his dexterity, his intellectual capacity, his sensitivity, his ability to dream, to imagine, to laugh.

If you can't fathom the effort he put into it, then no matter how hard I try to make you understand it, it won't work.

---From "Gilberte"

I held her cold hand tightly, tormented by self-reproach.

Dear Germain, you have helped me so much.

When I was frozen, you warmed me up.

You lent me your hand so I could finally fall asleep.

And yet I haven't had time to come see you, talk to you, see how you're building your life again—but you know, it took me a long time.

After that...

Yeah, even after I have time—I didn't come here to tell you what I owe you.

Just because I came back from there, because they didn't say these things there, I came.

(...)

You shouldn't feel ashamed.

You shouldn't feel regret.

What's the point of all that? It wasn't Sylvian who came back with us, it was Germain.

Was it yesterday or the day before, anyway, these days, since Sylvian is already dead, in the last few days, because Sylvian hasn't changed.

She, Germain, still has her generous lips, her blue-shining eyes, and the kindness and affection in them.

Germain's hand was still in my hand.

Even while sick, her hands were soft and plump, not thin, and I was holding her hands that had lost no flesh and had simply become transparent.

I was holding Germain's hand, unable to decide to leave, just as I had been there every night, unable to let go of my mother's hand, to fall asleep.

---From "The Death of Germain"

and

These are the stories of those who returned.

It would be better not to believe it.

These returning ghosts

I can't even explain how it happened

If you believe in these returning ghosts

You may never be able to sleep forever.

It is clearly distinguished from white snow.

It's in the middle of the yard.

Naked bodies.

They are lined up facing each other.

It's brand new.

It is a white color with a slightly bluish tint that is located above the eyes.

The head was completely shaved, and the hair on the pubic area stood up stiffly.

The corpses are frozen.

White, but the nails are brown.

The toes pointing up are a bit funny.

So absurd and horrific.

(...)

Now the mannequins are lying in the snow.

Soaked in the winter sun.

This sunlight reminds me of the sun on asphalt.

The mannequins lying in the snow are yesterday's classmates.

They were there yesterday, during roll call.

They stood in groups of five on either side of Lagerstrasse.

They set off for the workshop and headed towards the wetlands.

Yesterday they were hungry.

I scratched my body because I had teeth.

Yesterday they drank dirty soup.

They had diarrhea and were beaten.

Yesterday they were in pain.

Yesterday they wished to die.

Now they are here, naked corpses in the snow.

They are dead in block 25.

Death in Block 25 has neither the quiet nor the peace that is usually expected from death.

---From "Mannequin"

The eyes flash like sparks in the refracted light.

There is no spreading light, only the hard, cold light of ice.

Everything is carved with sharp outlines, as if it were cut off.

The sky is blue, solid, and frozen.

Plants trapped in glaciers come to mind.

This is something that could only happen in the Arctic, where glaciers freeze even underwater plants.

We are trapped in a block of ice like those plants.

In the ice, which is hard, sharp as if cut, and transparent, almost like crystal.

And light penetrates this crystal.

As if the light were frozen in the ice, or as if the ice itself were light.

It was only after a while that we realized that we could still move through this iceberg.

We wiggle our toes in our shoes and roll our feet on the floor.

Fifteen thousand women are stamping their feet, but there is no sound.

We are in an environment where time has been wasted.

In this ice, in this light, in these blindingly dazzling eyes, we cannot even tell whether we are there or not, this ice, this light, this silence.

---From "The Next Day"

I am again overcome with despair.

“How are we going to get out of here?”

Lully looks at me.

Smile at me.

Her hand touches mine gently, trying to comfort me.

And I repeat to her:

Please let her know that this is all for nothing.

“I clearly told you.

I can't do it today.

This time it's real."

Lully looks around us.

After making sure that no Capo is nearby, he grabs my wrist and says:

“Come behind me so I can’t see you.

“You can cry now,” she says shyly, in a low voice.

I'm sure he said this because he needed to hear it from me.

That's understandable, because if it's such kind encouragement, I'll follow it without hesitation.

I set my extension on the floor, lean on the handle, and cry.

I didn't want to cry.

But tears leak out and flow down my cheeks.

I let the tears flow.

And when a teardrop wets my lips, I feel a salty taste.

I keep crying.

Lully sees the net while working.

Every now and then she turns her body back and gently wipes my face with her sleeve.

I cry.

I don't think about anything anymore.

I cry.

When Lully pulled me, I no longer knew why I was crying.

“It’s done now.

Okay, let's get to work.

“Look, it’s okay now.” I wasn’t ashamed at all that I cried at such kind words.

It felt like I was crying in my mother's arms.

---From "Ryulyu"

You would have thought that only solemn words would come from the lips of the dying.

(...) Almost all of our comrades, lying naked on the shabby stretcher, said this.

“This time I’m going to die.”

They were naked on bare planks.

They were dirty, and the planks were dirty with diarrhea and lice.

They probably didn't know how hard this was.

The survivors are supposed to convey their last words to their parents.

Parents must have expected something grand.

I can't let them down.

Vulgar language would never be appropriate in an anthology of last words.

But I couldn't allow myself to become weak.

So they said this.

“This time, I’m going to die.” That was so as not to take away the courage of others.

They didn't leave anything that could be a message, because they thought not a single one would survive.

---From "You must have thought so"

At first, we wanted to sing.

You can't even imagine.

How my heart was torn to pieces by those frail voices repeating words that were now inconceivable, words that were shattered and weak in the swamp.

The dead do not sing.

...they started acting as soon as they came back to life.

(...)

It was amazing.

Some lines from Molière that were still fresh in our memories came rushing back.

He was brought back to life completely by some inexplicable magical power.

It was amazing.

Because everyone acted with sincerity, without trying to stand out, and with humility.

The miracle of actors without vanity.

A miracle for the audience, who suddenly regain their childhood innocence and revive their imagination.

It was amazing.

Because during those two hours, even as the smoke of human flesh billowed from the chimney, we believed more in the world we were acting in.

That belief was stronger than the belief in freedom, the only freedom we believed in at the time, the very freedom for which we had to fight for another 500 days.

---From "At first, I wanted to sing"

Each person took their own memories with them.

All that weight of memory, all that weight of the past.

When I arrived, I had to put all that weight down.

I had to take everything off and go in.

One might say that even if everything is taken away from a human, memories are the only exception.

But that's something you say without knowing anything.

Once you remove the attributes of human existence from a human being, their memories also disappear.

Memories fall off piece by piece, like burnt skin.

You will never understand how it is possible to survive so naked.

This is what I can't explain to you.

In the end, a few people survived like that.

People call things that cannot be explained a miracle.

The survivors had to regain their memories.

He had to get back what he once owned.

His knowledge, his experience, his childhood memories, his dexterity, his intellectual capacity, his sensitivity, his ability to dream, to imagine, to laugh.

If you can't fathom the effort he put into it, then no matter how hard I try to make you understand it, it won't work.

---From "Gilberte"

I held her cold hand tightly, tormented by self-reproach.

Dear Germain, you have helped me so much.

When I was frozen, you warmed me up.

You lent me your hand so I could finally fall asleep.

And yet I haven't had time to come see you, talk to you, see how you're building your life again—but you know, it took me a long time.

After that...

Yeah, even after I have time—I didn't come here to tell you what I owe you.

Just because I came back from there, because they didn't say these things there, I came.

(...)

You shouldn't feel ashamed.

You shouldn't feel regret.

What's the point of all that? It wasn't Sylvian who came back with us, it was Germain.

Was it yesterday or the day before, anyway, these days, since Sylvian is already dead, in the last few days, because Sylvian hasn't changed.

She, Germain, still has her generous lips, her blue-shining eyes, and the kindness and affection in them.

Germain's hand was still in my hand.

Even while sick, her hands were soft and plump, not thin, and I was holding her hands that had lost no flesh and had simply become transparent.

I was holding Germain's hand, unable to decide to leave, just as I had been there every night, unable to let go of my mother's hand, to fall asleep.

---From "The Death of Germain"

and

These are the stories of those who returned.

It would be better not to believe it.

These returning ghosts

I can't even explain how it happened

If you believe in these returning ghosts

You may never be able to sleep forever.

---From "A Prayer for the Living, To Forgive the Living"

Publisher's Review

* The profound horizons of Holocaust literature, as highlighted by philosopher Judith Butler and Nobel Peace Prize-winning author Elie Wiesel

* "We have a duty to raise the past from the ashes." Charlotte Delvaux, the playwright who unfolded the art of true memory from the depths of history, has her work published for the first time in Korea.

None of Us Will Return: Auschwitz and After is an experimental memoir by French playwright Charlotte Delvaux, which describes her experiences as an imprisoned woman in the death camp Auschwitz during World War II and the subsequent lives of the female resistance fighters who survived the hell together.

Delvaux was arrested in March 1942 while engaged in anti-Nazi activities under the Vichy regime in German-occupied France.

At the time, he was twenty-nine years old and was the secretary of the famous stage actor and director Louis Jouvet.

There were 230 French women on the train to Auschwitz that Delvaux was on, and only 49 of them returned alive after the war.

After returning in 1945, Delvaux wrote the three-volume series 'Auschwitz and After' over a period of 25 years.

Immediately after Delvaux's return, the manuscript of Parts 1 and 2, written based on his 27 months in the camp, lay dormant in a drawer for 20 years.

Delvaux decided to publish it in 1965, after conducting a thorough investigation of the women who had traveled on the train with him and compiling it into Le Convoi du 24 Janvier.

To reveal the truth about Auschwitz through the collective memory of women rather than through individual accounts, Delbo plans and writes three parts in the form of "testimonial literature" that transfer the lives of other survivors.

Through this process, the three volumes of memoirs published consecutively between 1965 and 1971 became the foundation for Delvaux's world of works, including numerous plays that delved into the issues of memory, knowledge, and language throughout her life, and were evaluated as having created a place for women who had remained in the shadows of history written in capital letters by state power and men's voices.

This experimental art form, with its narrative structure that resists linearity and its expressive methods that cross poetry, prose, and oral history through broken and continuous words, is constantly being reinterpreted across time in terms of philosophical and political questions about 'true memory and existence.'

Philosopher Judith Butler, in her 2023 collection of essays, The Livable and the Unlivable, draws heavily on Delvaux's case to continue her critical reflections on the language surrounding the displaced, refugee, and migrant lives in an age of violence and disconnection.

* “The 49 survivors, these strong women, were determined to survive and were adept at taking care of each other.

Among them was Charlotte Delvaux.” -Caroline Moorehead, author of Women of Auschwitz

* A women's narrative written in the voice of "us," rejecting state power and male history, and accompanying the deaths of their comrades to the very end.

After reading the book, Charlotte Delvaux will never be remembered as a single person.

In her camp records, the main subject is 'we', not 'I'.

Delvaux remembers and writes about his classmates who held each other's arms while walking, rubbed each other's bodies during roll call, became witnesses to each other's existence even in the midst of everyday life that made them lose their humanity, and called each other by name frequently so as not to lose each other.

At the bottom, women looked after each other.

It was also a matter of hanging on to life.

Because without each other, we would have fallen straight into the abyss of despair and the temptation of death.

The strength, courage, and meaning to endure in the camp were things that could never be maintained alone.

This togetherness kept Delvaux alive, but it also kept him company with death for the rest of his life.

The deaths of their comrades become ghosts that haunt the lives of survivors, persistently asking questions.

Why did another, stronger and braver woman die, and why did you live?

Whether we can, should, and what is the point of telling our truth, which only we know, to those who are not us.

If Delbo has any reason to survive, it is, above all, his responsibility for those deaths.

During her lifetime, she often said that she had a “moral obligation to raise the past from the ashes.”

So that the deaths of my colleagues do not become meaningless.

Therefore, the third part, which contains the events after the return, is an answer given by Delvaux through his earnest fulfillment of the duty he had given himself.

The lives she transcribed are shadows of grand narratives written by state power and male voices.

It is far removed from the mainstream historical narrative of overcoming tragedy and progress.

In reality, these female resistance fighters were ordinary women with low education and ordinary jobs.

(According to the Convoy of January 24th, about 160 of the 230 people had not received education beyond elementary school, and the majority were working class, including housewives, farmers, office workers, and seamstresses.) It was not out of a desire to become Joan of Arc, but out of conscience that these people took the beatings of those with weak motives and survived by holding on to each other, not because of a sense of honor.

There was no place for these women in the history of capital letters until then.

Delvaux's intense testimonial literature, which he unfolds not as a hero but as a fellow victim and mediator of memory, opens up the realm of the "afterdeath" of survivors, as Holocaust literature researcher Laurence Langer puts it, and raises profound questions about history in readers who dare to meet his gaze.

* “The challenge this book, one of the most important works on war, presents to us is to listen to the women’s voices, to capture simultaneously the beauty of their words and the enormity of their scenes.” —Elizabeth Holding, Woman’s Review of Books

* What is the memory that constitutes true existence, and what do knowledge and language do?

An artistic form worthy of being reinterpreted across time

The contemporary significance of this book lies above all in its experimental artistic form.

The rough, obsessive rhythm that arises from sentences that are abruptly interrupted, repeated in a halting manner, and barely breathable with the mouth and nose blocked is intertwined with the content and becomes a single mass.

It is the very nature of violence and absurdity that we face physically before we can know and think, and it is a form that embodies the ethics of survivors who, in Delvaux's own words, "must explain the inexplicable."

This body language, which dazzles all the senses, may have been considered somewhat difficult to understand at the time of its publication, but it has been consistently reinterpreted over time as a philosophical and political topic regarding 'true memory.'

Especially after 25 years since returning from Auschwitz, “for us, time does not pass.

It's not blurry at all.

The voices of women who confess that their lives are trapped in death and retelling, saying, “It does not wear out or wear out,” vividly portray the ghosts of history that will never become the past.

The experience of Auschwitz did not return as a medal, but as a nightmare, as an illness, as knowledge useless in the secular world, as insight accompanied by a deep emptiness, and as the resulting alienation and loneliness.

As Oka Mari describes in “Memory and Narrative,” the reality of the massive violence that “continues to return to the present tense” for the victims is chilling.

Therefore, the reason I am summoning Delvaux, a playwright little known in Korea, here and now, along with this old book and the forgotten past of the women's resistance, is not because she is another hero.

As someone who has peered into the abyss of humanity, as someone who has been in the most vulnerable state of being, as someone who has survived through solidarity with such beings, as someone who has taken upon himself the heavy responsibility for our deaths, and as someone who has faced squarely the time of life that has been deferred since then, the fierce words that Delvaux has protected while struggling with the failure of language still, or rather, day by day, sharply ask fundamental questions of life.

Was this world they had worked so hard to return to, this humanity they had so desperately wanted to embrace, truly worth it?

* "We have a duty to raise the past from the ashes." Charlotte Delvaux, the playwright who unfolded the art of true memory from the depths of history, has her work published for the first time in Korea.

None of Us Will Return: Auschwitz and After is an experimental memoir by French playwright Charlotte Delvaux, which describes her experiences as an imprisoned woman in the death camp Auschwitz during World War II and the subsequent lives of the female resistance fighters who survived the hell together.

Delvaux was arrested in March 1942 while engaged in anti-Nazi activities under the Vichy regime in German-occupied France.

At the time, he was twenty-nine years old and was the secretary of the famous stage actor and director Louis Jouvet.

There were 230 French women on the train to Auschwitz that Delvaux was on, and only 49 of them returned alive after the war.

After returning in 1945, Delvaux wrote the three-volume series 'Auschwitz and After' over a period of 25 years.

Immediately after Delvaux's return, the manuscript of Parts 1 and 2, written based on his 27 months in the camp, lay dormant in a drawer for 20 years.

Delvaux decided to publish it in 1965, after conducting a thorough investigation of the women who had traveled on the train with him and compiling it into Le Convoi du 24 Janvier.

To reveal the truth about Auschwitz through the collective memory of women rather than through individual accounts, Delbo plans and writes three parts in the form of "testimonial literature" that transfer the lives of other survivors.

Through this process, the three volumes of memoirs published consecutively between 1965 and 1971 became the foundation for Delvaux's world of works, including numerous plays that delved into the issues of memory, knowledge, and language throughout her life, and were evaluated as having created a place for women who had remained in the shadows of history written in capital letters by state power and men's voices.

This experimental art form, with its narrative structure that resists linearity and its expressive methods that cross poetry, prose, and oral history through broken and continuous words, is constantly being reinterpreted across time in terms of philosophical and political questions about 'true memory and existence.'

Philosopher Judith Butler, in her 2023 collection of essays, The Livable and the Unlivable, draws heavily on Delvaux's case to continue her critical reflections on the language surrounding the displaced, refugee, and migrant lives in an age of violence and disconnection.

* “The 49 survivors, these strong women, were determined to survive and were adept at taking care of each other.

Among them was Charlotte Delvaux.” -Caroline Moorehead, author of Women of Auschwitz

* A women's narrative written in the voice of "us," rejecting state power and male history, and accompanying the deaths of their comrades to the very end.

After reading the book, Charlotte Delvaux will never be remembered as a single person.

In her camp records, the main subject is 'we', not 'I'.

Delvaux remembers and writes about his classmates who held each other's arms while walking, rubbed each other's bodies during roll call, became witnesses to each other's existence even in the midst of everyday life that made them lose their humanity, and called each other by name frequently so as not to lose each other.

At the bottom, women looked after each other.

It was also a matter of hanging on to life.

Because without each other, we would have fallen straight into the abyss of despair and the temptation of death.

The strength, courage, and meaning to endure in the camp were things that could never be maintained alone.

This togetherness kept Delvaux alive, but it also kept him company with death for the rest of his life.

The deaths of their comrades become ghosts that haunt the lives of survivors, persistently asking questions.

Why did another, stronger and braver woman die, and why did you live?

Whether we can, should, and what is the point of telling our truth, which only we know, to those who are not us.

If Delbo has any reason to survive, it is, above all, his responsibility for those deaths.

During her lifetime, she often said that she had a “moral obligation to raise the past from the ashes.”

So that the deaths of my colleagues do not become meaningless.

Therefore, the third part, which contains the events after the return, is an answer given by Delvaux through his earnest fulfillment of the duty he had given himself.

The lives she transcribed are shadows of grand narratives written by state power and male voices.

It is far removed from the mainstream historical narrative of overcoming tragedy and progress.

In reality, these female resistance fighters were ordinary women with low education and ordinary jobs.

(According to the Convoy of January 24th, about 160 of the 230 people had not received education beyond elementary school, and the majority were working class, including housewives, farmers, office workers, and seamstresses.) It was not out of a desire to become Joan of Arc, but out of conscience that these people took the beatings of those with weak motives and survived by holding on to each other, not because of a sense of honor.

There was no place for these women in the history of capital letters until then.

Delvaux's intense testimonial literature, which he unfolds not as a hero but as a fellow victim and mediator of memory, opens up the realm of the "afterdeath" of survivors, as Holocaust literature researcher Laurence Langer puts it, and raises profound questions about history in readers who dare to meet his gaze.

* “The challenge this book, one of the most important works on war, presents to us is to listen to the women’s voices, to capture simultaneously the beauty of their words and the enormity of their scenes.” —Elizabeth Holding, Woman’s Review of Books

* What is the memory that constitutes true existence, and what do knowledge and language do?

An artistic form worthy of being reinterpreted across time

The contemporary significance of this book lies above all in its experimental artistic form.

The rough, obsessive rhythm that arises from sentences that are abruptly interrupted, repeated in a halting manner, and barely breathable with the mouth and nose blocked is intertwined with the content and becomes a single mass.

It is the very nature of violence and absurdity that we face physically before we can know and think, and it is a form that embodies the ethics of survivors who, in Delvaux's own words, "must explain the inexplicable."

This body language, which dazzles all the senses, may have been considered somewhat difficult to understand at the time of its publication, but it has been consistently reinterpreted over time as a philosophical and political topic regarding 'true memory.'

Especially after 25 years since returning from Auschwitz, “for us, time does not pass.

It's not blurry at all.

The voices of women who confess that their lives are trapped in death and retelling, saying, “It does not wear out or wear out,” vividly portray the ghosts of history that will never become the past.

The experience of Auschwitz did not return as a medal, but as a nightmare, as an illness, as knowledge useless in the secular world, as insight accompanied by a deep emptiness, and as the resulting alienation and loneliness.

As Oka Mari describes in “Memory and Narrative,” the reality of the massive violence that “continues to return to the present tense” for the victims is chilling.

Therefore, the reason I am summoning Delvaux, a playwright little known in Korea, here and now, along with this old book and the forgotten past of the women's resistance, is not because she is another hero.

As someone who has peered into the abyss of humanity, as someone who has been in the most vulnerable state of being, as someone who has survived through solidarity with such beings, as someone who has taken upon himself the heavy responsibility for our deaths, and as someone who has faced squarely the time of life that has been deferred since then, the fierce words that Delvaux has protected while struggling with the failure of language still, or rather, day by day, sharply ask fundamental questions of life.

Was this world they had worked so hard to return to, this humanity they had so desperately wanted to embrace, truly worth it?

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: November 15, 2024

- Page count, weight, size: 532 pages | 542g | 122*190*31mm

- ISBN13: 9791197971990

- ISBN10: 1197971998

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)