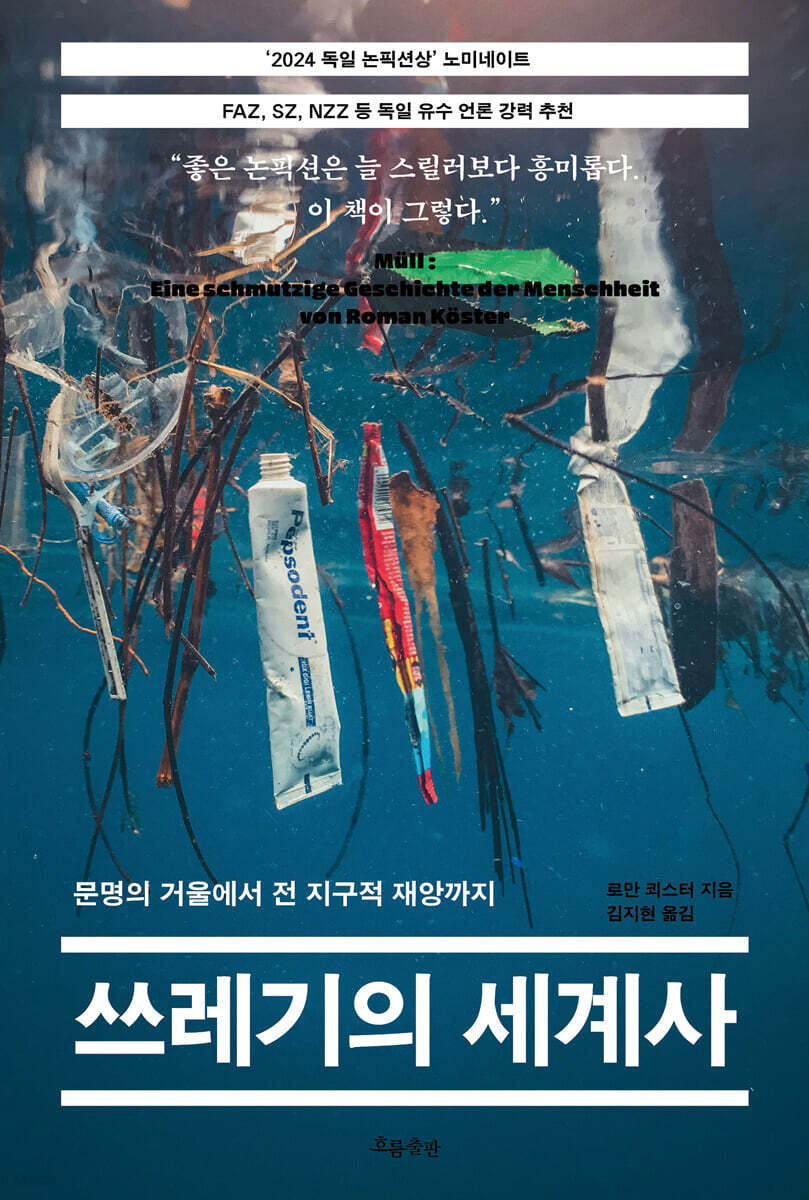

The World History of Garbage

|

Description

Book Introduction

Everything we throw away, burn, bury, and push away

The World's Frontline on Waste

The era has come when dead garbage overwhelms living beings.

The climate crisis caused by global warming threatens us with increasing intensity each day.

7.2 billion bees have disappeared, and two-thirds of the world's coral has turned white.

The species of fish in the sea have changed, and the places where agricultural products are grown have changed.

Winter is one month shorter and summer is one month longer.

After an unusually hot summer filled with torrential rain and scorching heat, we imagine next summer to be even longer and hotter.

In this age of climate crisis, where we cannot predict how the familiar four seasons will unfold, there is a "trash book" that can provide a clue to solving this problem.

The World's Frontline on Waste

The era has come when dead garbage overwhelms living beings.

The climate crisis caused by global warming threatens us with increasing intensity each day.

7.2 billion bees have disappeared, and two-thirds of the world's coral has turned white.

The species of fish in the sea have changed, and the places where agricultural products are grown have changed.

Winter is one month shorter and summer is one month longer.

After an unusually hot summer filled with torrential rain and scorching heat, we imagine next summer to be even longer and hotter.

In this age of climate crisis, where we cannot predict how the familiar four seasons will unfold, there is a "trash book" that can provide a clue to solving this problem.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Introduction

Part 1 · Pre-Modern: Life Comes with Trash

Chapter 1 - Prehistory: Where All This Waste Began

Chapter 2 - The Beginning of the City and Its Messy Development

Chapter 3 - Useful and Unclean Livestock of the City

Chapter 4 - The Teachings of Lack: Recycling the Premodern

Chapter 5 - Side Story: After Cleanliness and Uncleanliness, the Birth of 'Hygiene'

Part 2 · The Industrial Age: The Dawn of the Gray City

Chapter 6 - The Industrial Revolution: Reshaping the World

Chapter 7 - The Birth of the Trash Can

Chapter 8 - 'Superior Hygiene'?: The Pretext for Colonialism

Chapter 9 - The World Goes Round: Recycling in the Industrial Age

Part 3 · The Age of Mass Consumption: The Explosion of Waste

Chapter 10: The Birth of a Throwaway Society

Chapter 11 - Large Trash Cans and 'Male Pride'

Chapter 12 - Pushing Out, Discarding, Disposing of, Burying, and Burning

Chapter 13 - Poverty and Wealth: Policy and Recycling as a Survival Strategy

Epilogue - Trash Pushed into the Sea

Notes and References

Part 1 · Pre-Modern: Life Comes with Trash

Chapter 1 - Prehistory: Where All This Waste Began

Chapter 2 - The Beginning of the City and Its Messy Development

Chapter 3 - Useful and Unclean Livestock of the City

Chapter 4 - The Teachings of Lack: Recycling the Premodern

Chapter 5 - Side Story: After Cleanliness and Uncleanliness, the Birth of 'Hygiene'

Part 2 · The Industrial Age: The Dawn of the Gray City

Chapter 6 - The Industrial Revolution: Reshaping the World

Chapter 7 - The Birth of the Trash Can

Chapter 8 - 'Superior Hygiene'?: The Pretext for Colonialism

Chapter 9 - The World Goes Round: Recycling in the Industrial Age

Part 3 · The Age of Mass Consumption: The Explosion of Waste

Chapter 10: The Birth of a Throwaway Society

Chapter 11 - Large Trash Cans and 'Male Pride'

Chapter 12 - Pushing Out, Discarding, Disposing of, Burying, and Burning

Chapter 13 - Poverty and Wealth: Policy and Recycling as a Survival Strategy

Epilogue - Trash Pushed into the Sea

Notes and References

Detailed image

.jpg)

Into the book

“In the past, when labor productivity was low—before the industrialization of the 18th century—we produced very little waste, but today’s highly productive society—the one we live in—is on the verge of drowning in waste.

How can we explain the correlation between extremely high production efficiency and enormous resource waste? Waste is not something that wealthy societies can afford.

This is rather closer to a side effect of the wealth that society possesses.

The important thing is why we can throw away so much, how we can ignore this phenomenon.”

---From "Introductory Remarks"

“It is interesting to note how important urban reform and sanitation projects were as key technologies for colonial domination, but it is also worth examining how similar they were to colonial power’s approach and legitimacy claims.

The Germans were particularly strong in this argument, as they firmly believed themselves to be part of a colonial rivalry.

Qingdao, China, was a model and hygienic colony that was transformed into 'the cleanest city in Asia' when it fell into German hands at the turn of the 20th century.

…at the same time, intensive training was provided on proper behavior to eliminate contamination and achieve standards of physical hygiene.

“It goes without saying that this is a process for the development of civilization.”

---From Chapter 8, 'Superior Hygiene': A Pretext for Colonialism

“Bottle production was automated in 1903, and cellophane was first invented in 1913.

In the United States, brands centered around canned goods and cans began to form as early as the 1880s.

…the new packaging material has increased the speed of optimization.

Beginning in the 1950s, California oranges were packaged in paper boxes rather than wooden ones, and cans and tins also increased rapidly.

This period was marked by fundamental changes such as the emergence of supermarkets, department stores, self-service, and cash registers.

…technological innovations, changes in packaging and transportation systems, and new power sources have opened up unprecedented opportunities to leverage economies of scale and wage differentials in the production of goods.

…the economic changes that began with the increased need for packaging and the development of logistics systems—as well as the overproduction that followed—played a decisive role in the increase in the amount of waste.”

---From "The Birth of a Society of Throwaway Chapter 10"

“A lot of trash means profit.

Behind the process of mass-producing countless goods and easily making profits at low prices, there is waste.

Garbage makes our daily lives easier, saving us time and labor.

Modern transportation systems are not something that is irrelevant to us; they are a major factor in changing our behavior.

Receiving items by courier and eating fast food mean constant, comfortable, and fast consumption.

In this way, we become accomplices in a giant international garbage factory.

“The logistics transport system was a decisive factor in allowing, at least in some parts of the world, to shake off the burden of material shortages that had persisted for centuries in a matter of decades.”

---From "Epilogue: Trash Pushed into the Sea"

“The amount of plastic waste has been continuously increasing since the 1970s.

This problem took on a new dimension in the late 1980s.

For the first time, a massive patch of clumped debris – commonly called a garbage patch – has been captured in satellite imagery.

In 1997, oceanographer Charles J.

Moore brought attention to the mass of ocean garbage that later became known as the Great Pacific Garbage Patch (GPGP).

This island of trash, made mostly of plastic, is literally just the tip of the iceberg.

As time passes and microbes settle on the plastic, the island gradually collapses and sinks into the ocean.

Only one-fifth of all trash is floating on the surface of the water.

“A total of five giant garbage islands have been discovered in the ocean.”

How can we explain the correlation between extremely high production efficiency and enormous resource waste? Waste is not something that wealthy societies can afford.

This is rather closer to a side effect of the wealth that society possesses.

The important thing is why we can throw away so much, how we can ignore this phenomenon.”

---From "Introductory Remarks"

“It is interesting to note how important urban reform and sanitation projects were as key technologies for colonial domination, but it is also worth examining how similar they were to colonial power’s approach and legitimacy claims.

The Germans were particularly strong in this argument, as they firmly believed themselves to be part of a colonial rivalry.

Qingdao, China, was a model and hygienic colony that was transformed into 'the cleanest city in Asia' when it fell into German hands at the turn of the 20th century.

…at the same time, intensive training was provided on proper behavior to eliminate contamination and achieve standards of physical hygiene.

“It goes without saying that this is a process for the development of civilization.”

---From Chapter 8, 'Superior Hygiene': A Pretext for Colonialism

“Bottle production was automated in 1903, and cellophane was first invented in 1913.

In the United States, brands centered around canned goods and cans began to form as early as the 1880s.

…the new packaging material has increased the speed of optimization.

Beginning in the 1950s, California oranges were packaged in paper boxes rather than wooden ones, and cans and tins also increased rapidly.

This period was marked by fundamental changes such as the emergence of supermarkets, department stores, self-service, and cash registers.

…technological innovations, changes in packaging and transportation systems, and new power sources have opened up unprecedented opportunities to leverage economies of scale and wage differentials in the production of goods.

…the economic changes that began with the increased need for packaging and the development of logistics systems—as well as the overproduction that followed—played a decisive role in the increase in the amount of waste.”

---From "The Birth of a Society of Throwaway Chapter 10"

“A lot of trash means profit.

Behind the process of mass-producing countless goods and easily making profits at low prices, there is waste.

Garbage makes our daily lives easier, saving us time and labor.

Modern transportation systems are not something that is irrelevant to us; they are a major factor in changing our behavior.

Receiving items by courier and eating fast food mean constant, comfortable, and fast consumption.

In this way, we become accomplices in a giant international garbage factory.

“The logistics transport system was a decisive factor in allowing, at least in some parts of the world, to shake off the burden of material shortages that had persisted for centuries in a matter of decades.”

---From "Epilogue: Trash Pushed into the Sea"

“The amount of plastic waste has been continuously increasing since the 1970s.

This problem took on a new dimension in the late 1980s.

For the first time, a massive patch of clumped debris – commonly called a garbage patch – has been captured in satellite imagery.

In 1997, oceanographer Charles J.

Moore brought attention to the mass of ocean garbage that later became known as the Great Pacific Garbage Patch (GPGP).

This island of trash, made mostly of plastic, is literally just the tip of the iceberg.

As time passes and microbes settle on the plastic, the island gradually collapses and sinks into the ocean.

Only one-fifth of all trash is floating on the surface of the water.

“A total of five giant garbage islands have been discovered in the ocean.”

---From "Epilogue: Trash Pushed into the Sea"

Publisher's Review

“Who we are is revealed by what we let go of and how we let go of it.

Look in the trash can.

“You can learn more than you think.”

─ "ZEIT"

― Nominated for the 2024 German Nonfiction Award

― 'Best Science Books of 2024' Finalist

― Highly recommended by German media such as FAZ, SZ, and NZZ

When the things we push away overwhelm us

How to Write the Next History in the Age of Climate Crisis

The history of mankind is like the history of garbage.

Wherever there are humans, there has always been trash.

Neanderthals discarded useless items, and ancient Rome, like any 19th-century metropolis, struggled to deal with the ever-increasing volume of waste.

Garbage created the modern city.

Cities, which were struggling with the massive amounts of waste generated by large numbers of people, began to establish their own treatment infrastructure, such as collection systems and water networks.

And now we create new terrain with trash.

We pile up unprocessed trash to create a 'garbage mountain', we create a colorful 'garbage beach' that can be observed from space with clothes we throw away without wearing, and we create a giant 'garbage island' with plastic thrown into the ocean.

What is waste? Where does the waste we create go? How do we dispose of it? Despite all the processes of discarding, burying, burning, and chemically treating it, why does waste not disappear but instead "multiply"?

You can't solve the garbage problem without knowing what the garbage is.

Author Roman Köster, an expert on the post-World War II waste economy, writes “a history of the side effects of our waste” in the age of climate crisis, focusing on the waste production and disposal methods that are closely linked to capitalism.

From prehistoric times to the modern era of electronic waste, from the archaeology of garbage as a mirror of human civilization to the modern era of garbage colonies that push waste into poor countries, this book is a comprehensive and thorough study that transcends time and space, a "dirty history of humanity."

A world expert on the 'waste economy' speaks

In the age of excess waste,

The history of side effects we've used and discarded

The era of an unsustainable "waste tax" that transcends the Anthropocene

We live on what we have thrown away.

“This summer is the coolest summer of the rest of my life.” “Winter is one month shorter, summer is one month longer.” “A third of the world’s corals have turned white in the hot ocean waters.” Newspaper articles warning of an impending environmental disaster are overflowing.

Beyond global warming, we hear the term 'Earth Heating', and beyond climate change, we hear the term 'climate collapse'.

The word 'Wasteocene' also appeared in the word 'Anthropocene', which means a geological era formed by human influence.

Because when future generations look at the current geological strata, they will find it filled with pieces of plastic.

In a world where everything is disappearing, “waste is the only resource that increases.” Plastic is closely linked to the climate crisis.

Plastics emit greenhouse gases throughout their life cycle – from production to consumption, collection and disposal.

The plastic waste we produce every day is equivalent to the weight of 100 Eiffel Towers.

The amount of waste has continued to increase since the explosive growth immediately following World War II, and unless drastic measures are taken, household waste alone is projected to reach 3.4 billion tonnes by 2050, a 75% increase from today.

We haven't thought about how to dispose of waste as much as we have about convenient consumption.

The waste we cannot process is being dumped on the outskirts, to colonies, and to underdeveloped countries, and the waste is expanding the 'territory' of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch (GPGP).

Garbage as a mirror of civilization

Wherever there are humans, there is always garbage, and garbage testifies to human existence and way of life.

The history of waste began between 10,000 and 6000 BC, when humans began to settle in one place.

As humans settled in one place, they had to deal with excrement, food scraps, ash, and broken tools.

People dealt with their waste by 'throwing' it out of their houses and 'throwing' it into pits.

A Stone Age dump in Norway is 300 meters long and as tall as an eight-story building.

On the east bank of the Tiber River in Rome, Italy, there is a hill called Monte Testaccio.

This hill, 50 meters high and 1,000 meters in circumference, was formerly a large landfill.

“Urk, the largest city in Mesopotamia, not only used writing and writing, but also built a sewer system to carry away waste and excrement.

In Heracleopolis, ancient Egypt, during the 9th and 10th Dynasties (around 2170 BC), the waste of the nobles was already being collected en masse and discharged into the Nile River.

The Maya had a place to dump organic waste.

The Trojans appear to have simply thrown their garbage outside their doors, but Athens had street cleaning (koprologoi) and landfills as early as the 5th century BC.” (Page 34, Chapter 1, “Prehistory: The Beginning of All Waste”)

“The urban terrain had to be supported to allow the waste to flow away.

Having a slope or having the city on a mountain was a big advantage.

Rome, with its many mountains, was able to dispose of its waste relatively easily.

Rome channeled sewage and waste into the Tiber River through the Cloaca Maxima, an open sewer system built in the 6th century BC.

“Constantinople never had a major problem with waste throughout its long history, because the city was surrounded by a slope, allowing waste to be dumped into the turbulent waters of the Bosphorus Strait and the Sea of Marmara.” (Page 45, Chapter 2, “The City’s Beginnings and Messy Development”)

Trash, Creating a Developed City

As cities grow rapidly and population densities increase, the amount of waste also increases dramatically.

Garbage has finally emerged as a 'problem' in life.

As existing treatment methods reached their limits, city authorities began improving treatment "infrastructure," such as sewer network construction and garbage collection.

Cities in the 19th century evaluated the cleanliness of their neighbors, branding them as "dirty cities" or influencing each other by imitating them.

The 'trash can' was also invented through various attempts, failures, and successes, such as the publicization and privatization of the waste disposal entity, the development of disposal procedures and transportation methods, and the construction of roads that garbage trucks can enter.

It's no coincidence that giant yellow containers have become a familiar sight in urban residential areas.

“Berlin claims to be the cleanest city in the world, while simultaneously demoting Marseille to the dirtiest city in the world.

While New Yorkers, ashamed of their dirty streets, wanted to remove their name from the civilized city, fascism literally declared that it would cleanse Italy.

This continued after World War II, with waste being seen as a barometer of economic well-being.

In the 1950s, Americans admired the cleanliness of Swedish streets, free of beer and soft drink bottles.

Of course, it wasn't until a few years later that the consumer society arrived, and empty bottles began to pile up on Swedish streets." (pp. 267-268, Chapter 11, "Large Trash Cans and 'Men's Pride'")

As awareness of cleanliness arose and waste was identified as a cause of disease transmission, the concept of hygiene gradually emerged.

Each city created a hygiene journal to exchange knowledge, and the miasma theory, which held that diseases were caused by soil vapors, was replaced by bacteriology.

Bacteriologist William Sedgwick said:

“Before 1880 we knew nothing, but after the great decade of 1890 we knew everything.” Bacteriology was the turning point that marked the beginning of scientific urban sanitation.

The garbage that became the ruling logic of colonialism

Colonists presented the colonies with the ideal of a clean city with a waste disposal infrastructure, and thus an advanced city free of disease.

The colonial powers abolished local traditional waste disposal methods in the name of "sanitation projects" and intensively "educated" people on hygienic behavior in an attempt to "raise" hygiene standards to Western standards.

Of course, this is packaged as a process for the development of civilization.

“When the colonial rulers occupied Nairobi, Kenya, in 1889—in an attempt to regulate the city in its early stages, which was practically a lawless oasis—they paid particular attention to the cleanliness of the roads and the collection and disposal of waste.

The system worked generally well until the 1970s, before the city grew to become one of the largest in the world.

After the 1900s, the French began building facilities such as open water pipes, wells, and latrines in Madagascar.

“With the hope that such urban improvement projects would bolster the legitimacy of rule and make it easier to rule.” (p. 193, Chapter 8, “‘Superior Sanitation’?: A Pretext for Colonialism”)

Convenience creates new waste.

In 1969, Norwegian experimental archaeologist Thor Heyerdahl crossed the Pacific Ocean in a kayak he built himself.

What caught his eye was the vast amount of plastic waste floating on the ocean, something that hadn't been there just 15 years ago.

Plastic waste became a serious problem after the 1960s, when the consumption pattern called supermarkets spread around the world.

The process of 'optimizing sales' resulted in an oversupply of goods and the use of more packaging and shipping materials.

And today, decades later, none of us are free from plastic waste.

“Already in the 1950s, new mass production technologies reached our homes.

Refrigeration and packaging technology made it possible to purchase and store large quantities of groceries, usually in automobiles.

This led to mispredictions of demand and increased waste volumes.

Modern transportation technology has penetrated our actual consumption behavior and even into our mouths.

Of course, it was possible to optimize all the processes up to this point.

New materials have ushered in an era of greater consumption.

As product packaging technology developed, the demand for freshness increased.

New production and packaging methods have raised hygiene standards.

…since at least the 1960s, keeping one's home and body clean has become a duty.

New products for cleanliness, such as cleaning products, laundry detergents, and shampoos, are also appearing on the market one after another.” (Page 258, Chapter 10, “The Birth of a Throwaway Society”)

Piled, buried, burned, and eventually 'pushed out'

To the modern era of garbage colonies

In the 1970s, the existence of dioxin was first made known to the world.

People began to recognize the invisible but deadly threat posed by waste, and incineration began to be excluded as a disposal method.

Cities pushed their waste out of each other, and then out of the country.

A method of waste disposal that completely eliminates what has been produced has not yet been discovered.

So-called 'developed countries' are dumping the waste they cannot process at home onto underdeveloped countries.

“There are numerous grassroots groups in the United States opposing the construction of new incinerators.

The cross-border transport of waste has further aggravated public opinion.

Pennsylvania earned the notoriety of "Trashsylvania" in the late 1980s because it received so much trash from New York and other states that it had to build new facilities to process it.

In Japan, too, public resistance intensified, especially after dioxin was detected in the ash from incinerators in 1983.” (pp. 314-315, Chapter 12, “Push Out, Dispose of, Bury, Burn”)

“The dump was extremely flammable.

Not only was the waste highly flammable, but the heat generated by the fermentation of organic matter often led to spontaneous combustion.

… In 1993, 32 people were killed when 350,000 tons of garbage collapsed at the Umraniye landfill in Istanbul.

Bogotá's large landfill, Doña Juana, also experienced a similar incident in 1997.

The 2000 landslide at Manila's Smoky Mountain landfill officially killed about 200 people, but the actual number is believed to be much higher.” (pp. 306-307, Chapter 12, “Push, Dump, Dispose, Bury, Burn”)

Waste is becoming increasingly complex and the problem of waste disposal is becoming more difficult to solve.

Electronic waste (E-Waste) has been identified as a new cause of environmental pollution for over 20 years.

These wastes, made up of complex compounds, are usually dumped in landfills as special waste or buried in Ghana's infamous Agbogbloshie landfill.

'High-tech pollution' is added before even dealing with plastic waste.

The amount of waste that can be reduced by changing lifestyle is about 20%.

But for this 20%, the authors say we need to pay more attention to our daily lives and accept more restrictions.

And at the same time, we must look back at the economy that forces this production and consumption.

Products are always abundantly produced and waiting for us on the shelves, and after drinking a liter of beverage, we 'recycle' the remaining plastic bottle and turn away from the trash with satisfaction.

The trash we throw away now will outlive us.

“Good nonfiction is always more interesting than thrillers.

As one reader commented, “This book is like that.” “A World History of Waste” is a leading research book on waste that vividly shows the era of crisis before the readers’ eyes.

We are now five years away from reaching a point where the global average temperature rises 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels.

To stop the climate clock, it's time to look back at the trash we've thrown away and forgotten.

Look in the trash can.

“You can learn more than you think.”

─ "ZEIT"

― Nominated for the 2024 German Nonfiction Award

― 'Best Science Books of 2024' Finalist

― Highly recommended by German media such as FAZ, SZ, and NZZ

When the things we push away overwhelm us

How to Write the Next History in the Age of Climate Crisis

The history of mankind is like the history of garbage.

Wherever there are humans, there has always been trash.

Neanderthals discarded useless items, and ancient Rome, like any 19th-century metropolis, struggled to deal with the ever-increasing volume of waste.

Garbage created the modern city.

Cities, which were struggling with the massive amounts of waste generated by large numbers of people, began to establish their own treatment infrastructure, such as collection systems and water networks.

And now we create new terrain with trash.

We pile up unprocessed trash to create a 'garbage mountain', we create a colorful 'garbage beach' that can be observed from space with clothes we throw away without wearing, and we create a giant 'garbage island' with plastic thrown into the ocean.

What is waste? Where does the waste we create go? How do we dispose of it? Despite all the processes of discarding, burying, burning, and chemically treating it, why does waste not disappear but instead "multiply"?

You can't solve the garbage problem without knowing what the garbage is.

Author Roman Köster, an expert on the post-World War II waste economy, writes “a history of the side effects of our waste” in the age of climate crisis, focusing on the waste production and disposal methods that are closely linked to capitalism.

From prehistoric times to the modern era of electronic waste, from the archaeology of garbage as a mirror of human civilization to the modern era of garbage colonies that push waste into poor countries, this book is a comprehensive and thorough study that transcends time and space, a "dirty history of humanity."

A world expert on the 'waste economy' speaks

In the age of excess waste,

The history of side effects we've used and discarded

The era of an unsustainable "waste tax" that transcends the Anthropocene

We live on what we have thrown away.

“This summer is the coolest summer of the rest of my life.” “Winter is one month shorter, summer is one month longer.” “A third of the world’s corals have turned white in the hot ocean waters.” Newspaper articles warning of an impending environmental disaster are overflowing.

Beyond global warming, we hear the term 'Earth Heating', and beyond climate change, we hear the term 'climate collapse'.

The word 'Wasteocene' also appeared in the word 'Anthropocene', which means a geological era formed by human influence.

Because when future generations look at the current geological strata, they will find it filled with pieces of plastic.

In a world where everything is disappearing, “waste is the only resource that increases.” Plastic is closely linked to the climate crisis.

Plastics emit greenhouse gases throughout their life cycle – from production to consumption, collection and disposal.

The plastic waste we produce every day is equivalent to the weight of 100 Eiffel Towers.

The amount of waste has continued to increase since the explosive growth immediately following World War II, and unless drastic measures are taken, household waste alone is projected to reach 3.4 billion tonnes by 2050, a 75% increase from today.

We haven't thought about how to dispose of waste as much as we have about convenient consumption.

The waste we cannot process is being dumped on the outskirts, to colonies, and to underdeveloped countries, and the waste is expanding the 'territory' of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch (GPGP).

Garbage as a mirror of civilization

Wherever there are humans, there is always garbage, and garbage testifies to human existence and way of life.

The history of waste began between 10,000 and 6000 BC, when humans began to settle in one place.

As humans settled in one place, they had to deal with excrement, food scraps, ash, and broken tools.

People dealt with their waste by 'throwing' it out of their houses and 'throwing' it into pits.

A Stone Age dump in Norway is 300 meters long and as tall as an eight-story building.

On the east bank of the Tiber River in Rome, Italy, there is a hill called Monte Testaccio.

This hill, 50 meters high and 1,000 meters in circumference, was formerly a large landfill.

“Urk, the largest city in Mesopotamia, not only used writing and writing, but also built a sewer system to carry away waste and excrement.

In Heracleopolis, ancient Egypt, during the 9th and 10th Dynasties (around 2170 BC), the waste of the nobles was already being collected en masse and discharged into the Nile River.

The Maya had a place to dump organic waste.

The Trojans appear to have simply thrown their garbage outside their doors, but Athens had street cleaning (koprologoi) and landfills as early as the 5th century BC.” (Page 34, Chapter 1, “Prehistory: The Beginning of All Waste”)

“The urban terrain had to be supported to allow the waste to flow away.

Having a slope or having the city on a mountain was a big advantage.

Rome, with its many mountains, was able to dispose of its waste relatively easily.

Rome channeled sewage and waste into the Tiber River through the Cloaca Maxima, an open sewer system built in the 6th century BC.

“Constantinople never had a major problem with waste throughout its long history, because the city was surrounded by a slope, allowing waste to be dumped into the turbulent waters of the Bosphorus Strait and the Sea of Marmara.” (Page 45, Chapter 2, “The City’s Beginnings and Messy Development”)

Trash, Creating a Developed City

As cities grow rapidly and population densities increase, the amount of waste also increases dramatically.

Garbage has finally emerged as a 'problem' in life.

As existing treatment methods reached their limits, city authorities began improving treatment "infrastructure," such as sewer network construction and garbage collection.

Cities in the 19th century evaluated the cleanliness of their neighbors, branding them as "dirty cities" or influencing each other by imitating them.

The 'trash can' was also invented through various attempts, failures, and successes, such as the publicization and privatization of the waste disposal entity, the development of disposal procedures and transportation methods, and the construction of roads that garbage trucks can enter.

It's no coincidence that giant yellow containers have become a familiar sight in urban residential areas.

“Berlin claims to be the cleanest city in the world, while simultaneously demoting Marseille to the dirtiest city in the world.

While New Yorkers, ashamed of their dirty streets, wanted to remove their name from the civilized city, fascism literally declared that it would cleanse Italy.

This continued after World War II, with waste being seen as a barometer of economic well-being.

In the 1950s, Americans admired the cleanliness of Swedish streets, free of beer and soft drink bottles.

Of course, it wasn't until a few years later that the consumer society arrived, and empty bottles began to pile up on Swedish streets." (pp. 267-268, Chapter 11, "Large Trash Cans and 'Men's Pride'")

As awareness of cleanliness arose and waste was identified as a cause of disease transmission, the concept of hygiene gradually emerged.

Each city created a hygiene journal to exchange knowledge, and the miasma theory, which held that diseases were caused by soil vapors, was replaced by bacteriology.

Bacteriologist William Sedgwick said:

“Before 1880 we knew nothing, but after the great decade of 1890 we knew everything.” Bacteriology was the turning point that marked the beginning of scientific urban sanitation.

The garbage that became the ruling logic of colonialism

Colonists presented the colonies with the ideal of a clean city with a waste disposal infrastructure, and thus an advanced city free of disease.

The colonial powers abolished local traditional waste disposal methods in the name of "sanitation projects" and intensively "educated" people on hygienic behavior in an attempt to "raise" hygiene standards to Western standards.

Of course, this is packaged as a process for the development of civilization.

“When the colonial rulers occupied Nairobi, Kenya, in 1889—in an attempt to regulate the city in its early stages, which was practically a lawless oasis—they paid particular attention to the cleanliness of the roads and the collection and disposal of waste.

The system worked generally well until the 1970s, before the city grew to become one of the largest in the world.

After the 1900s, the French began building facilities such as open water pipes, wells, and latrines in Madagascar.

“With the hope that such urban improvement projects would bolster the legitimacy of rule and make it easier to rule.” (p. 193, Chapter 8, “‘Superior Sanitation’?: A Pretext for Colonialism”)

Convenience creates new waste.

In 1969, Norwegian experimental archaeologist Thor Heyerdahl crossed the Pacific Ocean in a kayak he built himself.

What caught his eye was the vast amount of plastic waste floating on the ocean, something that hadn't been there just 15 years ago.

Plastic waste became a serious problem after the 1960s, when the consumption pattern called supermarkets spread around the world.

The process of 'optimizing sales' resulted in an oversupply of goods and the use of more packaging and shipping materials.

And today, decades later, none of us are free from plastic waste.

“Already in the 1950s, new mass production technologies reached our homes.

Refrigeration and packaging technology made it possible to purchase and store large quantities of groceries, usually in automobiles.

This led to mispredictions of demand and increased waste volumes.

Modern transportation technology has penetrated our actual consumption behavior and even into our mouths.

Of course, it was possible to optimize all the processes up to this point.

New materials have ushered in an era of greater consumption.

As product packaging technology developed, the demand for freshness increased.

New production and packaging methods have raised hygiene standards.

…since at least the 1960s, keeping one's home and body clean has become a duty.

New products for cleanliness, such as cleaning products, laundry detergents, and shampoos, are also appearing on the market one after another.” (Page 258, Chapter 10, “The Birth of a Throwaway Society”)

Piled, buried, burned, and eventually 'pushed out'

To the modern era of garbage colonies

In the 1970s, the existence of dioxin was first made known to the world.

People began to recognize the invisible but deadly threat posed by waste, and incineration began to be excluded as a disposal method.

Cities pushed their waste out of each other, and then out of the country.

A method of waste disposal that completely eliminates what has been produced has not yet been discovered.

So-called 'developed countries' are dumping the waste they cannot process at home onto underdeveloped countries.

“There are numerous grassroots groups in the United States opposing the construction of new incinerators.

The cross-border transport of waste has further aggravated public opinion.

Pennsylvania earned the notoriety of "Trashsylvania" in the late 1980s because it received so much trash from New York and other states that it had to build new facilities to process it.

In Japan, too, public resistance intensified, especially after dioxin was detected in the ash from incinerators in 1983.” (pp. 314-315, Chapter 12, “Push Out, Dispose of, Bury, Burn”)

“The dump was extremely flammable.

Not only was the waste highly flammable, but the heat generated by the fermentation of organic matter often led to spontaneous combustion.

… In 1993, 32 people were killed when 350,000 tons of garbage collapsed at the Umraniye landfill in Istanbul.

Bogotá's large landfill, Doña Juana, also experienced a similar incident in 1997.

The 2000 landslide at Manila's Smoky Mountain landfill officially killed about 200 people, but the actual number is believed to be much higher.” (pp. 306-307, Chapter 12, “Push, Dump, Dispose, Bury, Burn”)

Waste is becoming increasingly complex and the problem of waste disposal is becoming more difficult to solve.

Electronic waste (E-Waste) has been identified as a new cause of environmental pollution for over 20 years.

These wastes, made up of complex compounds, are usually dumped in landfills as special waste or buried in Ghana's infamous Agbogbloshie landfill.

'High-tech pollution' is added before even dealing with plastic waste.

The amount of waste that can be reduced by changing lifestyle is about 20%.

But for this 20%, the authors say we need to pay more attention to our daily lives and accept more restrictions.

And at the same time, we must look back at the economy that forces this production and consumption.

Products are always abundantly produced and waiting for us on the shelves, and after drinking a liter of beverage, we 'recycle' the remaining plastic bottle and turn away from the trash with satisfaction.

The trash we throw away now will outlive us.

“Good nonfiction is always more interesting than thrillers.

As one reader commented, “This book is like that.” “A World History of Waste” is a leading research book on waste that vividly shows the era of crisis before the readers’ eyes.

We are now five years away from reaching a point where the global average temperature rises 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels.

To stop the climate clock, it's time to look back at the trash we've thrown away and forgotten.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: September 18, 2024

- Page count, weight, size: 428 pages | 584g | 145*215*21mm

- ISBN13: 9788965966494

- ISBN10: 8965966493

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)