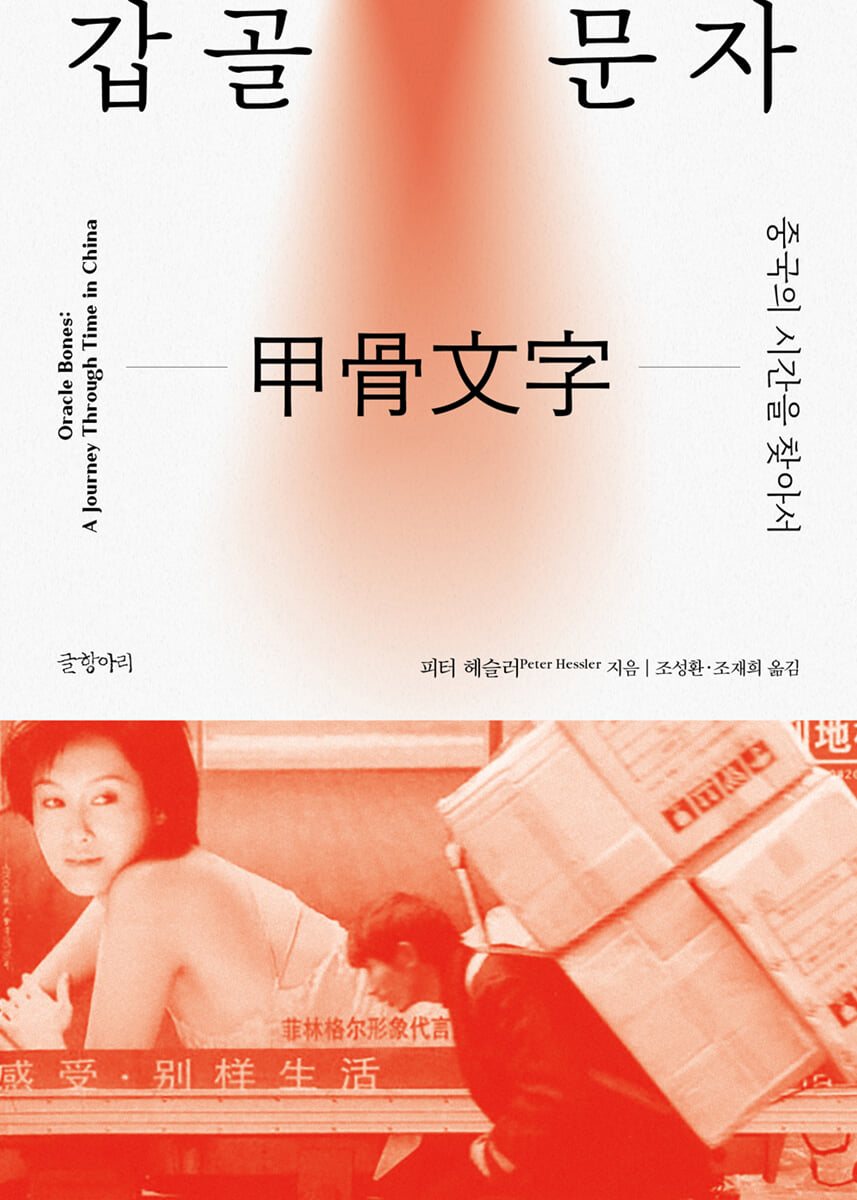

oracle bone script

|

Description

Book Introduction

'What do you think of us?'

Recovery and glory, patience and pride, anxiety and laughter, meaning and confusion,

Uncovering Modern China Through Revered Events and Forgotten Stories

From the oracle bone script of the ancient world to the revolutionary spirit of Tiananmen?

China, the Asian superpower where everything has changed rapidly throughout history.

Peter Hessler, an American journalist who visited this place, reflects on the human side of China's rapidly changing landscape through the ordinary people of its villages and streets.

Gracefully moving between ancient and modern times, East and West, this book unfolds the soul of a vast empire undergoing profound transformation before our eyes.

Recovery and glory, patience and pride, anxiety and laughter, meaning and confusion,

Uncovering Modern China Through Revered Events and Forgotten Stories

From the oracle bone script of the ancient world to the revolutionary spirit of Tiananmen?

China, the Asian superpower where everything has changed rapidly throughout history.

Peter Hessler, an American journalist who visited this place, reflects on the human side of China's rapidly changing landscape through the ordinary people of its villages and streets.

Gracefully moving between ancient and modern times, East and West, this book unfolds the soul of a vast empire undergoing profound transformation before our eyes.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Author's Note

Part 1

Artifact A: Underground City

Chapter 1: Broker

Artifact B: The World of Letters

Chapter 2 Voice of America

Chapter 3: The Broken Bridge

Artifact C: City Wall

Chapter 4: A City Built Overnight

Part 2

Chapter 5 Starch

Chapter 6 Hollywood

Relic D: The Sound of the Turtle

Chapter 7: Not Lonely at Night

Chapter 8 Immigration

Chapter 9: Siheyuan

Artifact E: Bronze Head

Chapter 10 Anniversary

Chapter 11 Sichuan People

Part 3

Artifact F: Book

Chapter 12 Political Exile

Artifact G: Unfinished bone

Chapter 13: The Olympic Games

Chapter 14 Sand

Artifact H: Letters

Chapter 15 Translation

Chapter 16 National Flag

Chapter 17: Video for Video Stores

Artifact I: Horses

Chapter 18: The Chaos of the Western

Chapter 19 Election

Part 4

Chapter 20 Chinatown

Relic J: Criticism

Chapter 21 State Visit

Relic K: The Lost Alphabet

Chapter 22: Encapsulating the Prime

Relic L: Mistranscribed letters

Chapter 23: General Patton's Tomb

Relic Z: Sold Letters

Chapter 24 Tea

source

Acknowledgements

Search

Part 1

Artifact A: Underground City

Chapter 1: Broker

Artifact B: The World of Letters

Chapter 2 Voice of America

Chapter 3: The Broken Bridge

Artifact C: City Wall

Chapter 4: A City Built Overnight

Part 2

Chapter 5 Starch

Chapter 6 Hollywood

Relic D: The Sound of the Turtle

Chapter 7: Not Lonely at Night

Chapter 8 Immigration

Chapter 9: Siheyuan

Artifact E: Bronze Head

Chapter 10 Anniversary

Chapter 11 Sichuan People

Part 3

Artifact F: Book

Chapter 12 Political Exile

Artifact G: Unfinished bone

Chapter 13: The Olympic Games

Chapter 14 Sand

Artifact H: Letters

Chapter 15 Translation

Chapter 16 National Flag

Chapter 17: Video for Video Stores

Artifact I: Horses

Chapter 18: The Chaos of the Western

Chapter 19 Election

Part 4

Chapter 20 Chinatown

Relic J: Criticism

Chapter 21 State Visit

Relic K: The Lost Alphabet

Chapter 22: Encapsulating the Prime

Relic L: Mistranscribed letters

Chapter 23: General Patton's Tomb

Relic Z: Sold Letters

Chapter 24 Tea

source

Acknowledgements

Search

Publisher's Review

Historical events are like stones thrown into a lake.

The waves spread with a loud noise, but the stones that fell to the bottom of the lake become deeply buried in the mud over time, and the water surface becomes calm again.

Since the reform and opening up, China's modernization has progressed dramatically and steeply, with many things surfacing and then sinking.

The birth of modern China, which began with the Shenzhen Special Economic Zone in the 1990s, continued with Shanghai in the 2000s, and then with the Beijing Olympics in 2008, created a lake as deep and wide as the journey of change.

Could we say that the shock of modernization is a crater that has been created within the human being who has experienced it?

The remnants of change that have sunk to the bottom, while not yet able to penetrate to the bottom, may reveal their natural colors through the rippling waves on a sunny day, arousing the desire of those who watch to unearth them.

If there is anyone who has ever looked at each stone thrown into the lake, and whenever he has a chance, hired a fisherman to go out to the center of the lake and look down at the bottom, and touch the texture of accumulated time interwoven and covered, Peter Hessler, author of Oracle Bones: A Journey Between China's Past and Present, is that person.

The original title of this book is Oracle Bones, which in Korean is oracle bone script.

Oracle bone script is an ancient script excavated from the ruins of Yin Ruins of the Shang Dynasty in China.

These hieroglyphs, modeled after nature or human actions, remain as the Yin Ruins Divination Code, which records the king's fortune-telling process, and give us a glimpse into the ancient world.

Letters exposed to sunlight are like codes to modern people, and their full meaning can only be revealed after deciphering them.

Wouldn't the same be true for Chinese time?

To the eyes of Western, and especially American, journalists, Chinese society would have been a difficult text to decipher.

The reason why this book on modern China is titled "Oracle Bone Script" may be the result of an impulsive grasp of the similarity in the act of interpretation.

In the book, the author does not tell us why.

“Just as all boundaries and definitions are sometimes fluid, so too is time itself.

(…) only replaces it with a short statement from the preface: “How to create historical meaning by going further into the past.”

At the time of writing the book, Peter Hessler was a news reporter for the Wall Street Journal's Beijing bureau.

His boss and supervisor was Ian Johnson, a journalist who won a Pulitzer Prize for his reporting on Falun Gong in 2001 (though Hessler may also have some credit). Until recently, Hessler taught English and British literature to students at a teachers' college in the small town of Fuling, Sichuan Province (now Fuling District, Chongqing).

As there was a teacher shortage at the time, his students were immediately assigned to middle and high school teachers across the country after graduation.

He gave his disciples names in English.

His two years at Fuling Normal School were compiled into a book called Rivertown, and he began his career as a freelance nonfiction writer, earning a living by writing articles about China for major English-language journals.

His boss, Johnson, soon kicked him out of the office, and he, now a non-journalist, began to observe China in earnest.

From 1999 to 2004, for five or six years, Hessler's 'lens' operated in a rather irregular manner, uncovering various layers of Chinese society. What he tried to read was mainly facial expressions, and he also traveled back in time by 3,000 years, following the directions given by the inner world of characters who mumbled their words and sometimes experiences that left irreparable scars.

Although this book is non-fiction, the expressions are very genre-complex and the structure itself is unique.

There are two main streams, one of which is the content from chapter 1 to chapter 24.

There are countless scenes and people mentioned along with a wide range of activities in China, the United States, Xinjiang, and Taiwan.

Coverage of Nanjing (protests against the bombing of the Chinese Embassy in Belgrade), the 10th anniversary of the Tiananmen Square Massacre, North Korea-related coverage in Dandong, a tour of Mount Baekdu, the sleepless city of Shenzhen, a starch manufacturing plant in Changchun, smuggling brokers off the coast of Fuzhou, Falun Gong demonstrations in Tiananmen Square, Hong Kong, and the demolition of Siheyuan Hutong in Beijing. These included the sensitive period of the NATO bombing in May 1999, the process of Beijing hosting the Olympic Games, the final stages of its application for WTO membership, the 2001 South China Sea maritime airspace collision, the 9/11 World Trade Center bombing, the East Turkestan issue, and US President Bush's visit to China.

Another is a journey from Artifact A to Artifact Z, following the excavation site of the Shang Dynasty Yin Ruins and interviewing related figures such as the excavation leader and current and former archaeologists.

These texts are inserted between chapters and, in fact, create a dreamlike atmosphere, like vignettes mistakenly inserted into reality, while mainly digging up past wounds.

The author takes the form of unraveling the tragic life of a scholar of oracle bone script named Chen Mengjia (1911-1966) and the mysteries surrounding him.

Former and current archaeologists at the Yin Ruins excavation site are suddenly transformed into witnesses due to their direct or indirect connection with Tian Mengzi, and are forced to embark on the arduous journey of testifying to a history they themselves do not fully understand.

The author interviews not only Chen Mengzi's senior and junior colleagues, but also the museum director, Li Xueqin, a leading figure in the archaeological community who personally attacked him, and even his 85-year-old younger brother Chen Mengxiong, a retired hydrogeologist. The author portrays in a three-dimensional way how Mao Zedong's anti-rightist struggle in 1957 destroyed the soul of an intellectual, but the result is far from a story with clear good and evil.

Interviewees include Uyghur Polat and his friends, archaeologist Jing Zichun, the pigeon keeper at the Nanjing Massacre Memorial Hall, Imre Galambos, a researcher of ancient Chinese culture, a veteran of the Korean War, Shi Zhanglu, a Taiwanese oracle bone scholar known as a “living dictionary,” Tang Jigan, the head of the Anyang Archaeological Excavation Team, Hu Xiaomei, a radio host at Shenzhen Broadcasting Station, novelist Miao Yong, Zhao Jingxin from Beijing, Professor Robert Bagley, a bronze ware researcher, archaeologist Xu Chaolong, Xu Wenqiu, the discoverer of the Sanxingdui Golden Mask, Chen Xiandan, deputy director of the Sichuan Provincial Museum, Yang Shizhang, an Anyang archaeologist, Wu Ningkun, an American Chinese national, tracing the life of oracle bone inscription scholar Chen Mengzi through Mr. Zhao, David Kitley, a scholar of oracle bone inscriptions, Liu Jingmin, the deputy mayor of Beijing, coverage of the 29th Beijing Olympics held in 2008, Xu Jicheng, a former basketball player and broadcaster who also participated in the 1988 Seoul Olympics. Among the participants are American anthropologist John McCalloun, history professor Alfred Sen, villagers and police officers met at the scene of the village chief election in Xitou District, oracle bone script scholar Professor Kenichi Takashima, Shi Zhangtao of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Tian Xin, director of the International Affairs Department of the Democratic Progressive Party of Taiwan, Lin Zhengjie, deputy mayor of Hsinchu City, Taiwan, independent Taiwanese legislator Chen Wenchen, anthropologist Shi Lei of the Academia Sinica in Taiwan, Meme Omer Kanat, a correspondent for Radio Free Asia in the US, Ma Chengyuan of the Shanghai Museum, Li Xueqin, the director of the "Xia-Shang-Zhu Dan-Da Project" and an ancient scholar, American linguist John DeFrancis, senior linguists Zhou Youguang, Yin Binyong, and Wang Jun, Ministry of Education official Zhang Lianzhong, Chen Mengxiong's younger brother Chen Mengxiong, Arlington National Cemetery in Washington, Chen Mengxiong's disciple Wang Shimin, Tian Zhicheng, director of the Wuwei Museum, Chinese studies professor Victor Meyer, and film director Zhang Wen.

What would it be like to create historical meaning by moving away from the past?

Perhaps it means understanding the complex dynamics of history.

The author traces the life of Cheon Meng-ja while also covering the scenes where history is constantly being made.

In Chapter 9, which deals with the tug-of-war between the district government's attempt to demolish the 400-year-old Siheyuan in Beijing's Jur Hutong and the 82-year-old landlord, Zhao Jingxin, who risks his life to stop it, Hessler records a story through intensive interviews that leaves a strange and bitter aftertaste.

“Hutongs and Siheyuans do not exist in other countries.

“This house is older than America,” the old man said.

This is followed by a speech about the old government's excessive administration and the historical value of Siheyuan.

He countered with a complaint, and the old man, who argued that the only old villages left in China were Pingyao in the north and Lijiang in the southwest, said, “As a Chinese, I have a responsibility to protect this place.

I will not back down on my own.

“To them, I just say two words: ‘Not moving.’”

Demolition was the fate of Beijing and other changing metropolises.

Hessler suggests a character that symbolizes it.

It is the letter '?' (difference).

In Beijing, the word is plastered on buildings slated for demolition, and can be seen throughout the city's older areas.

“The letters are usually written in a circle about 1 meter in size, like the anarchist symbol A.” Since ? is seen everywhere, puns using it have also been created.

“We live in ‘China Day’.” This sounds like the English word China.

The elderly man's lawsuit against the former government attracted the attention of Chinese reporters.

I went back after being interviewed on television, but it didn't make the news.

As time went by, all the houses in Zhuerhutong turned into bricks and dust.

The only ones left are Zhao Jingxin and his wife.

The old man's attitude became increasingly harsh.

“The court officials will come, the police will come, and an ambulance will come.

“It will be worth seeing when that time comes.” However, the day before the forced execution, the old man abandons the house and leaves voluntarily.

The elderly couple left, but around 8:30 a.m., more than 50 police officers surrounded the demolition site and workers with pickaxes arrived, breaking up bricks and spraying water on the dust.

Lime, mud, brick.

Dust, dust, dust.

?, ?, ?.

By late afternoon, Siheyuan had become history.

The daily wages of the workers who made that history were less than $2.50.

On the other hand, how much money did the old man receive in compensation?

That isn't even written in the margins.

Good and evil, tradition and modernity, harm and perpetrator.

It was a complex issue that could not be interpreted in one way.

This book contains many snapshots of China's changing landscape through the eyes of students who have become school teachers.

As a teacher, he continued to interact with his students who had graduated.

Among them, Emily, who went to Shenzhen, and William Foster, who went to Yuanzhou, each portray the changes in the two major cities through a single lens, and these are synthesized by Hessler.

Through Emily, who gave up on becoming a teacher and took a job as an English teacher at a factory in Shenzhen, various stories unfold about this incredible city that sprang up overnight, dividing the inner and outer parts of the city by a huge wall.

Hu Xiaomei, a night radio host who reads and gives advice on the exploitation and misappropriation of labor by bosses who mainly came from Taiwan, and the loneliness and stories of young people who left their hometown; Miao Yong, a 29-year-old novelist whose novels captured Shenzhen so well that they were banned; Emily, her student who dislikes her novels because they are money-grubbing stories targeting white-collar workers in Shenzhen; and Zhu Yunfeng, who lives with her.

Hessler, an outsider, sees “the fragmentation of propaganda, like a lonely person far from home,” and wonders “how all this will ultimately come together into something cohesive.”

“What difference will that make in China?” the author asked his student Emily, but to the 24-year-old, such a question was not particularly important.

Emily anonymously sent a death threat to her boss, who had recently been harassing her, for talking back to her.

To the teacher's question, he smiled and answered, "I don't know."

William Foster, who went to Yuanzhou in Zhejiang Province, is the most impressive character in this book.

He was a maniac who loved English, who sincerely wanted to be good at it, and who, in a letter to his teacher, shamelessly made obscene remarks like, “Doesn’t the little bird sing in the morning?” He was a truly country-like person who obsessively studied the elements of civilization called language to survive in an era of change.

He was invited to a school in a small town near Yuanzhou with Nancy, whom he met during his time at teacher's college, but in the process, he paid large bribes twice due to paperwork issues, but ended up falling victim to a hiring scam.

Mr. Wang, who invited him and took him with him, often told William, who was from Sichuan, that when he was young, he traveled in northern Sichuan and could not hold back tears when he saw the poor people living in terrible conditions.

This meant that he should be grateful that he had brought him out of Sichuan, even though he had brought him to a place that was not even a school and paid low wages that bordered on hiring fraud.

Of all the things William detested about Mr. Wang, including his stern, stingy, and mischievous nature, it was his sympathy for this Sichuan man that he found most detestable.

William escapes Mr. Wang and gets a decent job in a town called Weqing, but he has to be careful when walking at night because people sometimes steal manhole covers and sell them for scrap metal.

His fellow teacher, who had mastered Mandarin perfectly and was passing himself off as a native of neighboring Jiangsu, was furious, saying, "The Sichuan immigrants stole it."

William made no answer.

William continued to study English through the radio broadcast "Voice of America," and read three English dictionaries after graduating from college.

Finally, William participated in an English competition held in the fall of 2000 and won first place among 500 teachers.

“It’s an honor.

“I think the reason I was able to win was because I was crazy.”

But like Emily in the propaganda, William in Wechsler soon encounters a great social injustice.

That was an educational official who took bribes and stole entrance exam questions.

William's school was a public school, but it was competing with schools in surrounding cities, so bribes were always paid.

However, the civil servant did not properly report the problem even after receiving a bribe.

On the first day of the exam, a parent came to the teacher, William, and told him that Beethoven and Bill Gates would be on the exam tomorrow.

With the statement that it is from a reliable source.

William, at a copy shop far from the school, photocopied pages from the parent's child's textbook with profiles of two famous foreigners and distributed them to the students, giving them strict instructions.

Just study this and don't tell anyone.

Soon the test results were announced, and William's class had the highest scores in the entire school.

The principal gave him a bonus of 6,000 yuan.

If only Beethoven had been on the list, I would have received more money.

But eventually, William anonymously reports this college entrance exam corruption scandal involving schools and educational officials to a local broadcasting station.

There was a lot of buzz in the news and investigations were conducted.

Author Hessler asked William why he took the risk.

“I did it for rural students.

When this happens, only city students will be informed.

“This is unfair to rural students.”

These newcomers to society were swept up in the flow of Chinese modernization, sometimes conforming to the system and sometimes resisting it, as seen in the Oracle Bone Script.

Perhaps China's modernization was also a process of Chinese people encountering foreign countries within their country through their fluid lives.

Unfamiliar language, distinct customs, and exclusive wariness have made it difficult to adapt to a foreign country within the country, and have made it difficult to focus on real foreign or global issues.

Hessler was asked the question “What do you think” most often in China.

At protest sites, in restaurants, and while traveling through the border region of Dandong, Hessler was constantly confronted with this direct question from the Chinese.

The Chinese both admired and hated America.

He wanted to hear the American people's opinions, but he also wanted to criticize them.

The older I got, the more it was like that.

Even though they were young, most of them had limited access to the media and were inclined towards nationalism.

One time, someone saved him from a really dire situation.

It was none other than the dollar scalper Polat from Beijing Yabao Road.

Polat was a school teacher and intellectual in Uyghur, but he was oppressed by the government and ended up in the back alleys of Beijing, where he settled as a broker.

Pollat sold anything.

In 1998, he made $2,000 by arranging the sale of two truckloads of counterfeit 555 brand shoes to a trade consortium from Poland, Romania, and Yugoslavia.

Another day, some Russians helped buy a container of fake Nautica clothes from an underground factory in Tianjin, earning $1,000.

1998 was a smooth year.

That year, he persuaded a Russian to buy 20,000 counterfeit bras made in Guangdong under the Pierre Cardin brand, earning about 25 cents apiece.

However, he wanted to seek asylum in the United States and devote himself to the Uyghur independence movement.

No, I wanted to throw off the huge burden called China and become free.

As he became acquainted with Polat, the author began to experience the lives of ethnic minorities in the back alleys of Beijing.

Prostitutes from Kazakh, Uzbek, Tatar, Mongolian and Russian origins.

They even had a drink with him.

Then, political discussions inevitably came up.

They were in favor of NATO bombing.

Hessler asked.

“Do you approve of what NATO did to Yugoslavia?” “Of course I do.

The reason Albanians were killed was because they were a minority.

We know what happened there because we listen to the Voice of America.

I think this is important because I am a Uyghur from Xinjiang.

“Do you understand what I mean?” Hessler nodded, but he stared at him intently.

“Mingbai le ma 明白了??” (Do you understand?) “I know.” “There are many things in Beijing that are difficult to talk about openly.

“Do you understand?” “Yes.”

There are famous China-expert journalists in world history.

They include Nym Wales (1907-1997), who reconstructed the life of Korean revolutionary Kim San through 22 interviews, Anna Louise Strong (1885-1970), Agnes Smedley (1892-1950), and Edgar Snow (1905-1972), known as the '3S'.

These are all journalists who interviewed leaders during the revolutionary period in mainland China and reported this to the Western world.

Peter Hessler is a recent addition to this list.

Born on June 14, 1969, in Columbia, Missouri, he studied English literature at Princeton University and received a master's degree in English literature from Oxford University.

At the age of 27, he was dispatched to China as a member of the Peace Corps and taught English at Fuling Normal College (now Changjiang Normal College) for two years. Afterwards, he worked as a Beijing-based reporter for The New Yorker and contributed to National Geographic and The Wall Street Journal for a long time.

In 2011, he left for Cairo, Egypt, to report on the Egyptian Revolution and publish a book. He then returned to China and criticized the Chinese education system, leading to his permanent expulsion by the Chinese government.

The content is scheduled to be included in a book published in English in 2024.

His wife is Leslie T. Chang, a 1991 Harvard graduate.

It's Chang.

She is also an American writer who writes about China, and her work includes Factory Girls: From Village to City in a Changing China (2008).

Peter Hessler, who was praised by the Wall Street Journal as “the most insightful Western writer on modern China,” lived in China for ten years from 1996 to 2007, interviewing and traveling, and published his experiences in a trilogy of Chinese reportage books, “River Town,” “Oracle Bone Script,” and “Country Driving,” which won several book awards and were selected as Book of the Year.

Among them, 『River Town-』 and 『Country Driving』 have already been translated and introduced in Korea.

The last of the Chinese trilogy, 『Oracle Bone Script』(2006), is a type of travel literature that was written by personally traveling to various places in mainland China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and the United States, at the intersection of the 20th and 21st centuries.

Incidentally, this book, which deals with the Xinjiang Uyghur issue as a major topic, is the only one of Hessler's trilogy that has not been published in a continental edition.

This is because the government cannot tolerate activities related to the independence of East Turkestan by Chinese Muslims residing in the United States.

It was published in Taiwan in 2007 under the title “Oracle Bone Script: A New China Floating in Time and Space.”

The waves spread with a loud noise, but the stones that fell to the bottom of the lake become deeply buried in the mud over time, and the water surface becomes calm again.

Since the reform and opening up, China's modernization has progressed dramatically and steeply, with many things surfacing and then sinking.

The birth of modern China, which began with the Shenzhen Special Economic Zone in the 1990s, continued with Shanghai in the 2000s, and then with the Beijing Olympics in 2008, created a lake as deep and wide as the journey of change.

Could we say that the shock of modernization is a crater that has been created within the human being who has experienced it?

The remnants of change that have sunk to the bottom, while not yet able to penetrate to the bottom, may reveal their natural colors through the rippling waves on a sunny day, arousing the desire of those who watch to unearth them.

If there is anyone who has ever looked at each stone thrown into the lake, and whenever he has a chance, hired a fisherman to go out to the center of the lake and look down at the bottom, and touch the texture of accumulated time interwoven and covered, Peter Hessler, author of Oracle Bones: A Journey Between China's Past and Present, is that person.

The original title of this book is Oracle Bones, which in Korean is oracle bone script.

Oracle bone script is an ancient script excavated from the ruins of Yin Ruins of the Shang Dynasty in China.

These hieroglyphs, modeled after nature or human actions, remain as the Yin Ruins Divination Code, which records the king's fortune-telling process, and give us a glimpse into the ancient world.

Letters exposed to sunlight are like codes to modern people, and their full meaning can only be revealed after deciphering them.

Wouldn't the same be true for Chinese time?

To the eyes of Western, and especially American, journalists, Chinese society would have been a difficult text to decipher.

The reason why this book on modern China is titled "Oracle Bone Script" may be the result of an impulsive grasp of the similarity in the act of interpretation.

In the book, the author does not tell us why.

“Just as all boundaries and definitions are sometimes fluid, so too is time itself.

(…) only replaces it with a short statement from the preface: “How to create historical meaning by going further into the past.”

At the time of writing the book, Peter Hessler was a news reporter for the Wall Street Journal's Beijing bureau.

His boss and supervisor was Ian Johnson, a journalist who won a Pulitzer Prize for his reporting on Falun Gong in 2001 (though Hessler may also have some credit). Until recently, Hessler taught English and British literature to students at a teachers' college in the small town of Fuling, Sichuan Province (now Fuling District, Chongqing).

As there was a teacher shortage at the time, his students were immediately assigned to middle and high school teachers across the country after graduation.

He gave his disciples names in English.

His two years at Fuling Normal School were compiled into a book called Rivertown, and he began his career as a freelance nonfiction writer, earning a living by writing articles about China for major English-language journals.

His boss, Johnson, soon kicked him out of the office, and he, now a non-journalist, began to observe China in earnest.

From 1999 to 2004, for five or six years, Hessler's 'lens' operated in a rather irregular manner, uncovering various layers of Chinese society. What he tried to read was mainly facial expressions, and he also traveled back in time by 3,000 years, following the directions given by the inner world of characters who mumbled their words and sometimes experiences that left irreparable scars.

Although this book is non-fiction, the expressions are very genre-complex and the structure itself is unique.

There are two main streams, one of which is the content from chapter 1 to chapter 24.

There are countless scenes and people mentioned along with a wide range of activities in China, the United States, Xinjiang, and Taiwan.

Coverage of Nanjing (protests against the bombing of the Chinese Embassy in Belgrade), the 10th anniversary of the Tiananmen Square Massacre, North Korea-related coverage in Dandong, a tour of Mount Baekdu, the sleepless city of Shenzhen, a starch manufacturing plant in Changchun, smuggling brokers off the coast of Fuzhou, Falun Gong demonstrations in Tiananmen Square, Hong Kong, and the demolition of Siheyuan Hutong in Beijing. These included the sensitive period of the NATO bombing in May 1999, the process of Beijing hosting the Olympic Games, the final stages of its application for WTO membership, the 2001 South China Sea maritime airspace collision, the 9/11 World Trade Center bombing, the East Turkestan issue, and US President Bush's visit to China.

Another is a journey from Artifact A to Artifact Z, following the excavation site of the Shang Dynasty Yin Ruins and interviewing related figures such as the excavation leader and current and former archaeologists.

These texts are inserted between chapters and, in fact, create a dreamlike atmosphere, like vignettes mistakenly inserted into reality, while mainly digging up past wounds.

The author takes the form of unraveling the tragic life of a scholar of oracle bone script named Chen Mengjia (1911-1966) and the mysteries surrounding him.

Former and current archaeologists at the Yin Ruins excavation site are suddenly transformed into witnesses due to their direct or indirect connection with Tian Mengzi, and are forced to embark on the arduous journey of testifying to a history they themselves do not fully understand.

The author interviews not only Chen Mengzi's senior and junior colleagues, but also the museum director, Li Xueqin, a leading figure in the archaeological community who personally attacked him, and even his 85-year-old younger brother Chen Mengxiong, a retired hydrogeologist. The author portrays in a three-dimensional way how Mao Zedong's anti-rightist struggle in 1957 destroyed the soul of an intellectual, but the result is far from a story with clear good and evil.

Interviewees include Uyghur Polat and his friends, archaeologist Jing Zichun, the pigeon keeper at the Nanjing Massacre Memorial Hall, Imre Galambos, a researcher of ancient Chinese culture, a veteran of the Korean War, Shi Zhanglu, a Taiwanese oracle bone scholar known as a “living dictionary,” Tang Jigan, the head of the Anyang Archaeological Excavation Team, Hu Xiaomei, a radio host at Shenzhen Broadcasting Station, novelist Miao Yong, Zhao Jingxin from Beijing, Professor Robert Bagley, a bronze ware researcher, archaeologist Xu Chaolong, Xu Wenqiu, the discoverer of the Sanxingdui Golden Mask, Chen Xiandan, deputy director of the Sichuan Provincial Museum, Yang Shizhang, an Anyang archaeologist, Wu Ningkun, an American Chinese national, tracing the life of oracle bone inscription scholar Chen Mengzi through Mr. Zhao, David Kitley, a scholar of oracle bone inscriptions, Liu Jingmin, the deputy mayor of Beijing, coverage of the 29th Beijing Olympics held in 2008, Xu Jicheng, a former basketball player and broadcaster who also participated in the 1988 Seoul Olympics. Among the participants are American anthropologist John McCalloun, history professor Alfred Sen, villagers and police officers met at the scene of the village chief election in Xitou District, oracle bone script scholar Professor Kenichi Takashima, Shi Zhangtao of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Tian Xin, director of the International Affairs Department of the Democratic Progressive Party of Taiwan, Lin Zhengjie, deputy mayor of Hsinchu City, Taiwan, independent Taiwanese legislator Chen Wenchen, anthropologist Shi Lei of the Academia Sinica in Taiwan, Meme Omer Kanat, a correspondent for Radio Free Asia in the US, Ma Chengyuan of the Shanghai Museum, Li Xueqin, the director of the "Xia-Shang-Zhu Dan-Da Project" and an ancient scholar, American linguist John DeFrancis, senior linguists Zhou Youguang, Yin Binyong, and Wang Jun, Ministry of Education official Zhang Lianzhong, Chen Mengxiong's younger brother Chen Mengxiong, Arlington National Cemetery in Washington, Chen Mengxiong's disciple Wang Shimin, Tian Zhicheng, director of the Wuwei Museum, Chinese studies professor Victor Meyer, and film director Zhang Wen.

What would it be like to create historical meaning by moving away from the past?

Perhaps it means understanding the complex dynamics of history.

The author traces the life of Cheon Meng-ja while also covering the scenes where history is constantly being made.

In Chapter 9, which deals with the tug-of-war between the district government's attempt to demolish the 400-year-old Siheyuan in Beijing's Jur Hutong and the 82-year-old landlord, Zhao Jingxin, who risks his life to stop it, Hessler records a story through intensive interviews that leaves a strange and bitter aftertaste.

“Hutongs and Siheyuans do not exist in other countries.

“This house is older than America,” the old man said.

This is followed by a speech about the old government's excessive administration and the historical value of Siheyuan.

He countered with a complaint, and the old man, who argued that the only old villages left in China were Pingyao in the north and Lijiang in the southwest, said, “As a Chinese, I have a responsibility to protect this place.

I will not back down on my own.

“To them, I just say two words: ‘Not moving.’”

Demolition was the fate of Beijing and other changing metropolises.

Hessler suggests a character that symbolizes it.

It is the letter '?' (difference).

In Beijing, the word is plastered on buildings slated for demolition, and can be seen throughout the city's older areas.

“The letters are usually written in a circle about 1 meter in size, like the anarchist symbol A.” Since ? is seen everywhere, puns using it have also been created.

“We live in ‘China Day’.” This sounds like the English word China.

The elderly man's lawsuit against the former government attracted the attention of Chinese reporters.

I went back after being interviewed on television, but it didn't make the news.

As time went by, all the houses in Zhuerhutong turned into bricks and dust.

The only ones left are Zhao Jingxin and his wife.

The old man's attitude became increasingly harsh.

“The court officials will come, the police will come, and an ambulance will come.

“It will be worth seeing when that time comes.” However, the day before the forced execution, the old man abandons the house and leaves voluntarily.

The elderly couple left, but around 8:30 a.m., more than 50 police officers surrounded the demolition site and workers with pickaxes arrived, breaking up bricks and spraying water on the dust.

Lime, mud, brick.

Dust, dust, dust.

?, ?, ?.

By late afternoon, Siheyuan had become history.

The daily wages of the workers who made that history were less than $2.50.

On the other hand, how much money did the old man receive in compensation?

That isn't even written in the margins.

Good and evil, tradition and modernity, harm and perpetrator.

It was a complex issue that could not be interpreted in one way.

This book contains many snapshots of China's changing landscape through the eyes of students who have become school teachers.

As a teacher, he continued to interact with his students who had graduated.

Among them, Emily, who went to Shenzhen, and William Foster, who went to Yuanzhou, each portray the changes in the two major cities through a single lens, and these are synthesized by Hessler.

Through Emily, who gave up on becoming a teacher and took a job as an English teacher at a factory in Shenzhen, various stories unfold about this incredible city that sprang up overnight, dividing the inner and outer parts of the city by a huge wall.

Hu Xiaomei, a night radio host who reads and gives advice on the exploitation and misappropriation of labor by bosses who mainly came from Taiwan, and the loneliness and stories of young people who left their hometown; Miao Yong, a 29-year-old novelist whose novels captured Shenzhen so well that they were banned; Emily, her student who dislikes her novels because they are money-grubbing stories targeting white-collar workers in Shenzhen; and Zhu Yunfeng, who lives with her.

Hessler, an outsider, sees “the fragmentation of propaganda, like a lonely person far from home,” and wonders “how all this will ultimately come together into something cohesive.”

“What difference will that make in China?” the author asked his student Emily, but to the 24-year-old, such a question was not particularly important.

Emily anonymously sent a death threat to her boss, who had recently been harassing her, for talking back to her.

To the teacher's question, he smiled and answered, "I don't know."

William Foster, who went to Yuanzhou in Zhejiang Province, is the most impressive character in this book.

He was a maniac who loved English, who sincerely wanted to be good at it, and who, in a letter to his teacher, shamelessly made obscene remarks like, “Doesn’t the little bird sing in the morning?” He was a truly country-like person who obsessively studied the elements of civilization called language to survive in an era of change.

He was invited to a school in a small town near Yuanzhou with Nancy, whom he met during his time at teacher's college, but in the process, he paid large bribes twice due to paperwork issues, but ended up falling victim to a hiring scam.

Mr. Wang, who invited him and took him with him, often told William, who was from Sichuan, that when he was young, he traveled in northern Sichuan and could not hold back tears when he saw the poor people living in terrible conditions.

This meant that he should be grateful that he had brought him out of Sichuan, even though he had brought him to a place that was not even a school and paid low wages that bordered on hiring fraud.

Of all the things William detested about Mr. Wang, including his stern, stingy, and mischievous nature, it was his sympathy for this Sichuan man that he found most detestable.

William escapes Mr. Wang and gets a decent job in a town called Weqing, but he has to be careful when walking at night because people sometimes steal manhole covers and sell them for scrap metal.

His fellow teacher, who had mastered Mandarin perfectly and was passing himself off as a native of neighboring Jiangsu, was furious, saying, "The Sichuan immigrants stole it."

William made no answer.

William continued to study English through the radio broadcast "Voice of America," and read three English dictionaries after graduating from college.

Finally, William participated in an English competition held in the fall of 2000 and won first place among 500 teachers.

“It’s an honor.

“I think the reason I was able to win was because I was crazy.”

But like Emily in the propaganda, William in Wechsler soon encounters a great social injustice.

That was an educational official who took bribes and stole entrance exam questions.

William's school was a public school, but it was competing with schools in surrounding cities, so bribes were always paid.

However, the civil servant did not properly report the problem even after receiving a bribe.

On the first day of the exam, a parent came to the teacher, William, and told him that Beethoven and Bill Gates would be on the exam tomorrow.

With the statement that it is from a reliable source.

William, at a copy shop far from the school, photocopied pages from the parent's child's textbook with profiles of two famous foreigners and distributed them to the students, giving them strict instructions.

Just study this and don't tell anyone.

Soon the test results were announced, and William's class had the highest scores in the entire school.

The principal gave him a bonus of 6,000 yuan.

If only Beethoven had been on the list, I would have received more money.

But eventually, William anonymously reports this college entrance exam corruption scandal involving schools and educational officials to a local broadcasting station.

There was a lot of buzz in the news and investigations were conducted.

Author Hessler asked William why he took the risk.

“I did it for rural students.

When this happens, only city students will be informed.

“This is unfair to rural students.”

These newcomers to society were swept up in the flow of Chinese modernization, sometimes conforming to the system and sometimes resisting it, as seen in the Oracle Bone Script.

Perhaps China's modernization was also a process of Chinese people encountering foreign countries within their country through their fluid lives.

Unfamiliar language, distinct customs, and exclusive wariness have made it difficult to adapt to a foreign country within the country, and have made it difficult to focus on real foreign or global issues.

Hessler was asked the question “What do you think” most often in China.

At protest sites, in restaurants, and while traveling through the border region of Dandong, Hessler was constantly confronted with this direct question from the Chinese.

The Chinese both admired and hated America.

He wanted to hear the American people's opinions, but he also wanted to criticize them.

The older I got, the more it was like that.

Even though they were young, most of them had limited access to the media and were inclined towards nationalism.

One time, someone saved him from a really dire situation.

It was none other than the dollar scalper Polat from Beijing Yabao Road.

Polat was a school teacher and intellectual in Uyghur, but he was oppressed by the government and ended up in the back alleys of Beijing, where he settled as a broker.

Pollat sold anything.

In 1998, he made $2,000 by arranging the sale of two truckloads of counterfeit 555 brand shoes to a trade consortium from Poland, Romania, and Yugoslavia.

Another day, some Russians helped buy a container of fake Nautica clothes from an underground factory in Tianjin, earning $1,000.

1998 was a smooth year.

That year, he persuaded a Russian to buy 20,000 counterfeit bras made in Guangdong under the Pierre Cardin brand, earning about 25 cents apiece.

However, he wanted to seek asylum in the United States and devote himself to the Uyghur independence movement.

No, I wanted to throw off the huge burden called China and become free.

As he became acquainted with Polat, the author began to experience the lives of ethnic minorities in the back alleys of Beijing.

Prostitutes from Kazakh, Uzbek, Tatar, Mongolian and Russian origins.

They even had a drink with him.

Then, political discussions inevitably came up.

They were in favor of NATO bombing.

Hessler asked.

“Do you approve of what NATO did to Yugoslavia?” “Of course I do.

The reason Albanians were killed was because they were a minority.

We know what happened there because we listen to the Voice of America.

I think this is important because I am a Uyghur from Xinjiang.

“Do you understand what I mean?” Hessler nodded, but he stared at him intently.

“Mingbai le ma 明白了??” (Do you understand?) “I know.” “There are many things in Beijing that are difficult to talk about openly.

“Do you understand?” “Yes.”

There are famous China-expert journalists in world history.

They include Nym Wales (1907-1997), who reconstructed the life of Korean revolutionary Kim San through 22 interviews, Anna Louise Strong (1885-1970), Agnes Smedley (1892-1950), and Edgar Snow (1905-1972), known as the '3S'.

These are all journalists who interviewed leaders during the revolutionary period in mainland China and reported this to the Western world.

Peter Hessler is a recent addition to this list.

Born on June 14, 1969, in Columbia, Missouri, he studied English literature at Princeton University and received a master's degree in English literature from Oxford University.

At the age of 27, he was dispatched to China as a member of the Peace Corps and taught English at Fuling Normal College (now Changjiang Normal College) for two years. Afterwards, he worked as a Beijing-based reporter for The New Yorker and contributed to National Geographic and The Wall Street Journal for a long time.

In 2011, he left for Cairo, Egypt, to report on the Egyptian Revolution and publish a book. He then returned to China and criticized the Chinese education system, leading to his permanent expulsion by the Chinese government.

The content is scheduled to be included in a book published in English in 2024.

His wife is Leslie T. Chang, a 1991 Harvard graduate.

It's Chang.

She is also an American writer who writes about China, and her work includes Factory Girls: From Village to City in a Changing China (2008).

Peter Hessler, who was praised by the Wall Street Journal as “the most insightful Western writer on modern China,” lived in China for ten years from 1996 to 2007, interviewing and traveling, and published his experiences in a trilogy of Chinese reportage books, “River Town,” “Oracle Bone Script,” and “Country Driving,” which won several book awards and were selected as Book of the Year.

Among them, 『River Town-』 and 『Country Driving』 have already been translated and introduced in Korea.

The last of the Chinese trilogy, 『Oracle Bone Script』(2006), is a type of travel literature that was written by personally traveling to various places in mainland China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and the United States, at the intersection of the 20th and 21st centuries.

Incidentally, this book, which deals with the Xinjiang Uyghur issue as a major topic, is the only one of Hessler's trilogy that has not been published in a continental edition.

This is because the government cannot tolerate activities related to the independence of East Turkestan by Chinese Muslims residing in the United States.

It was published in Taiwan in 2007 under the title “Oracle Bone Script: A New China Floating in Time and Space.”

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: November 30, 2023

- Format: Hardcover book binding method guide

- Page count, weight, size: 768 pages | 150*210*40mm

- ISBN13: 9791169090780

- ISBN10: 1169090788

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)