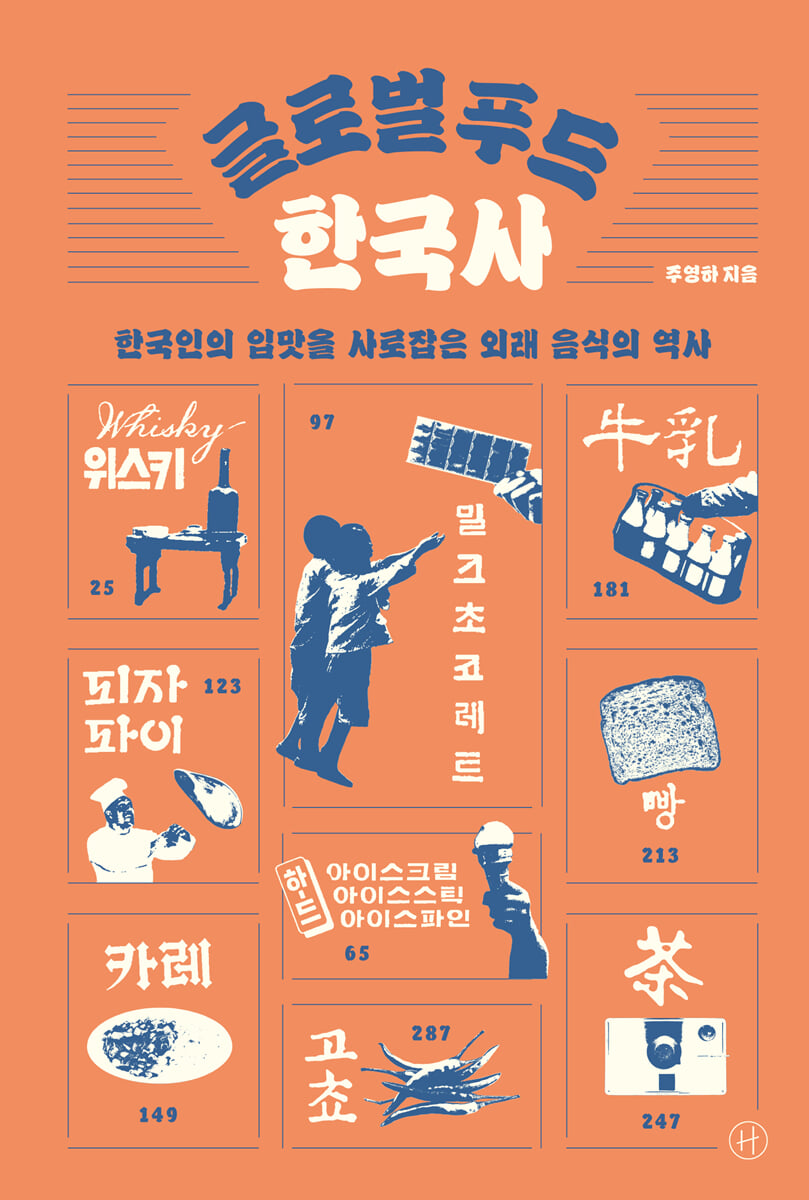

Global Food Korean History

|

Description

Book Introduction

From the arrival of foreign foods to the rise of K-food

Spread out on the Korean table

Korean history of foods from across the sea

A world where fake whiskey reigns supreme, the sigh of an ice cream vendor in the hot summer, the outstretched hand shouting “Give me chocolate,” ‘curry’ that has become ‘curry,’ the world’s most expensive Korean bread, the true identity of kimchi, which turned out to be a global food…

Although their introduction dates, motives, and methods differ, countless global foods have found their way onto Korean tables and captivated our taste buds! Let's delve into the history of foreign foods introduced to the Korean Peninsula, guided by Professor Joo Young-ha, a trusted food humanist.

The sweet, salty, spicy, and bitter history of Korean food culture, created by nine global foods, unfolds in a delicious way.

Spread out on the Korean table

Korean history of foods from across the sea

A world where fake whiskey reigns supreme, the sigh of an ice cream vendor in the hot summer, the outstretched hand shouting “Give me chocolate,” ‘curry’ that has become ‘curry,’ the world’s most expensive Korean bread, the true identity of kimchi, which turned out to be a global food…

Although their introduction dates, motives, and methods differ, countless global foods have found their way onto Korean tables and captivated our taste buds! Let's delve into the history of foreign foods introduced to the Korean Peninsula, guided by Professor Joo Young-ha, a trusted food humanist.

The sweet, salty, spicy, and bitter history of Korean food culture, created by nine global foods, unfolds in a delicious way.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Preface: My Global Food Experience

Prologue: When and how did global food enter the Korean Peninsula?

―Global Food Era in Korean Food History

1 Whiskey: A World Where Counterfeit Whiskey Runs the Run

2 Ice Cream: The sweet and cold taste that soothes the heat of the Korean Peninsula

3 Chocolate: The country that shouted “Give me chocolate”

4 Pizzas: From Pizza Pie to Korean Pizza

5 Curry: Is Korean 'curry' a derivative of Japanese 'curry'?

6 Milk: The History of Milk Embracing Modern and Contemporary Korean History

7 Bread: Why Bread Is Expensive in Korea

8th: Why didn't the people of the Korean Peninsula drink tea?

9 Spices: Exploring the Long History of Korean Spices

Epilogue: Korean Food Evolving into Global Cuisine and Global Food

― The future of K-food

Notes in the text

Image source and location

Prologue: When and how did global food enter the Korean Peninsula?

―Global Food Era in Korean Food History

1 Whiskey: A World Where Counterfeit Whiskey Runs the Run

2 Ice Cream: The sweet and cold taste that soothes the heat of the Korean Peninsula

3 Chocolate: The country that shouted “Give me chocolate”

4 Pizzas: From Pizza Pie to Korean Pizza

5 Curry: Is Korean 'curry' a derivative of Japanese 'curry'?

6 Milk: The History of Milk Embracing Modern and Contemporary Korean History

7 Bread: Why Bread Is Expensive in Korea

8th: Why didn't the people of the Korean Peninsula drink tea?

9 Spices: Exploring the Long History of Korean Spices

Epilogue: Korean Food Evolving into Global Cuisine and Global Food

― The future of K-food

Notes in the text

Image source and location

Detailed image

Publisher's Review

1.

When and how did global food enter the Korean Peninsula?

―Global Food in Korean Food History

This book covers the Korean history of global foods that Koreans naturally eat and drink, including whiskey, ice cream, chocolate, pizza, curry, milk, bread, tea, and spices, even though they are not native to Korea.

With the migration of people since ancient times, food ingredients and foods have also spread around the world, and this globalization of food has influenced the society and culture of each country, creating 'global food.'

There are already numerous global foods on the Korean table.

Chili peppers have been localized for a very long time and have become an indispensable ingredient in Korean food. Fruits such as bananas and oranges, as well as foreign snacks and sauces, can be easily found, and foods such as ramen, chicken, and pizza have been 'Koreanized' to capture the taste buds of people not only in Korea but also around the world.

When and how did these global foods, which have so profoundly transformed Korean diets and food culture, arrive on the Korean Peninsula? Professor Joo Young-ha, the author of this book, explains, "Just as no culture in the world has survived untouched by its surroundings, food is no exception. Therefore, Korean food is also a product of exchange and hybridization." He examines the history of global foods across eight distinct periods in Korean history.

The period is the Three Kingdoms period when Buddhist culture was introduced from China, the Goryeo Dynasty under the influence of the Mongol Empire and the Yuan Dynasty, the era of the Columbian Exchange when American crops were transported around the world, the late Joseon Dynasty when exchanges with China and Japan were active, the period of port opening and colonial rule when foreign foods were introduced in earnest, the period after the Korean War and liberation when Korea had to rely on aid from the United States and the United Nations, the compressed growth period when the food industry grew significantly, and the post-globalization period when American-style fast food restaurants appeared and Korean food began to spread around the world.

Nine global foods tell the story of their origins, their arrival on the Korean Peninsula, their "Koreanization," and the reactions and social impact of contemporary people who encountered them, all based on rich literature and images.

By introducing the Korean history of foreign foods, which could easily have become a blank space in world history and Korean history, we propose another perspective on Korean food culture.

Of course, some of the ingredients in food considered 'traditional Korean food' originate from other countries.

The cabbage used in Korean kimchi originated from seeds brought by Chinese immigrants from Shandong Province, China in the early 20th century.

Chili peppers were also brought to the Korean Peninsula from Central America on European ships about 500 years ago, after going through many twists and turns, and cultivation began there.

Foods that are leading the globalization of Korean food today, such as chicken, dakgalbi, and tteokbokki, first appeared in the 1960s.

The chicken was created by combining soybean oil extracted from American soybeans, soybean meal, and American wheat flour.

The slide cheese used in dakgalbi and tteokbokki since the 2010s is also an industrial cheese developed in the United States.

―From the Prologue (page 13)

About 100 years after the end of the war known as the Imjin War, new crops such as peppers, pumpkins, corn, and potatoes were growing in Joseon.

Their origin is the American continent.

These crops, loaded onto Portuguese and Spanish trading ships, crossed the Atlantic Ocean to Europe, and then traveled through the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia to arrive on the Korean Peninsula.

The chili peppers covered in this book also entered the Korean Peninsula in this way and became an indispensable seasoning in cooking since the mid-18th century.

The exchange of goods between the American and Eurasian continents after 1492 is called the 'Columbus Exchange', and the red color and spicy flavor that have become symbols of Korean food today are the results of the Columbian Exchange.

―From the Prologue (page 16)

2.

The past 100 years of Korean life captured in global food

―The taste and memories of food that all generations read and share together.

Excluding agricultural products that were introduced to the Korean Peninsula a long time ago and made cultivation possible, most of the global foods that Koreans enjoy in their daily lives today do not have a long history.

Moreover, Korean society, which has experienced rapid changes over the past 100 years such as colonization, war, economic growth, and globalization, is home to multiple generations with different experiences.

So, individual experiences and perceptions of global food may differ.

In other words, each global food covered in this book embodies the changing face of Korean society, while also reflecting the lives of everyone who has lived through that change.

The history of whiskey, which officially entered the Korean Peninsula in 1882 with the signing of the Treaty of Amity and Commerce between Korea and the United States, includes stories of Korean whiskey that are as exciting as the birthplace of whiskey, including 'Hanyang Sanghoe', which first directly imported whiskey during the Korean Empire, 'Modern Boy' who enjoyed whiskey at a 'cafe' in Gyeongseong, 'pseudo-whiskey' produced from the colonial period to after liberation and various crimes that resulted from it, whiskey made by the Korean government to provide to soldiers, and Korea's 'bomb shot' culture of mixing liquor and beer.

Although the history of ice is so long that ice storage facilities have been built since the Silla Dynasty, ice cream was introduced to the Korean Peninsula through modern Japan.

It brings back sweet memories of ice cream, including the ice cream sold on the streets after the Korean War, the Samgang Hard that was released when factory production began in the 1960s, the popularity of Bravocon and Nuga Bar in the 1970s, and the story of the Korean ice cream industry expanding into the world.

Chocolate is a global food that reminds Koreans of the pain and hunger of war, when they cried out “Give me chocolate” to the UN forces.

However, through the pursuit of the fantasy of chocolate while celebrating Valentine's Day during the compressed growth period, we can also see the conflicting images of chocolate as exploitation and enjoyment in the history of the Korean Peninsula.

In Korea, where bread is not a staple food, the history of bread is special.

Nowadays, handmade bread made with good ingredients is attracting attention, rather than the factory-made bread sold in supermarkets.

However, the reality is that franchises run by large corporations still dominate the Korean bakery industry.

Here, we will tell the story of bread introduced to the Korean Peninsula from Japan in the late 19th century, as well as how mass-produced factory bread spread throughout Korean society after liberation in keeping with the times.

In addition, there are many stories about global foods, such as the milk that children had to drink every day to grow up healthy, the curry udon that they were forced to eat due to the mixed meal promotion movement, the green tea that was shunned as “water made with boiled shiitake mushrooms,” and the first pizza restaurant and American fast food restaurant in Korea.

The author suggests that this book be a catalyst for engaging in 'food chat' with family, friends, colleagues, and neighbors.

The global food experience shared by individuals and communities will become another record, further enriching the history of Korean food culture.

As the demand for whiskey increased and the supply from US military bases became scarce, Japanese whiskey was smuggled in.

Among Japanese whiskies, 'Torys Whiskey' made by Suntory was popular.

…As demand for whiskey increased, some manufacturers even began manufacturing similar products.

At the current 'International Brewery' in Toseong-dong, Seo-gu, Busan, a similar product to Tory's whiskey was manufactured and sold.

The name of this distillery's whiskey was 'Doris', not 'Torys'.

… but Doris Whiskey was a whiskey in name only, without a single drop of whiskey essence.

―From “Whiskey: A World Where Counterfeit Whiskey Runs Wild” (pp. 54-56)

After the war, the number of stores selling 'ice cakes' frozen with ammonia increased rapidly in cities across the country, including Seoul.

At that time, ice cream was a frozen block of ice made by putting red bean paste in sugar water with yellow coloring and sticking it on a wooden skewer.

… The names of representative ice creams sold in Seoul in the 1950s were ‘Seokbinggo’ and ‘Angko.’

Boys from poor families ran through the alleys shouting, carrying buckets of ice cream.

The front of the city's theaters and schools where sports days were held were also good places to sell ice cream.

But hygiene was still a problem.

At that time, ice cream was considered a junk food.

―From “Ice Cream: The Sweet and Cold Flavor That Soothed the Korean Peninsula’s Heat” (p. 88)

For Koreans who experienced the Korean War, chocolate was a delicious and novel food, but it did not remain as a solely positive memory.

A Korean born in the 1940s who experienced such dire poverty that he had no choice but to shout “Give me chocolate” to American soldiers.

They played a leading role in trade as the 'Chocolate English Generation' during the economic development of the Park Chung-hee regime in the 1960s.

… So, they would have been even more determined to ‘live well’ even under dictatorship and oppression.

―From “Chocolate: The Country That Shouted “Give Me Chocolate”” (pp. 113, 114)

We cannot say that all the bread that Koreans ate in the 1960s and 1970s was mass-produced.

At that time, there was always a famous bakery in the center of any city, including Seoul.

In particular, the number of privately run bakeries increased rapidly in the 1960s when the government stepped in to promote snacks.

At that time, almost two-thirds of the bakery names were Japanese names such as ‘○○dang’ or ‘○○sa.’

The influence of the bakeries run by Japanese residents during the colonial period continued until the 1960s.

… bakeries that opened after the mid-1950s were named after Western countries or cities.

German bakery, New York bakery, New Chicago, etc.

It was a result of Western influence intervening in the bread industry after the Korean War.

As bakery names like 'Germany' or 'New York' suggest, names of prosperous regions in the West also attracted consumers' attention.

―From “Why Bread is Expensive in Korea” (pp. 243, 244)

3.

K-Food's Advancement to Global Food: What's the Future?

―A vision for K-food proposed by food humanist Professor Joo Young-ha

Just as countless global foods entered the Korean Peninsula and underwent a process of Koreanization, Korean food, as it spreads around the world, will also undergo a process of localization in each region.

In this book, the author not only tells the history of global foods that have entered the Korean Peninsula, but also examines the current state of K-food, which is gaining global attention.

The book's epilogue examines the evolution of specific regional foods and food products into global foods by type, and by applying examples such as kimchi, ramen, and seaweed, it captures the transformation of K-food into global foods.

In addition, it does not miss the critical view of the "food nationalism" that blindly criticizes the way people around the world consume K-food differently from Koreans, who are only concerned with the amount of food exported without any consideration for the preservation of Korea's unique food culture, and the mass production system of the global distribution network that is accelerating the climate crisis.

This perspective on K-food as a global food presents a vision for the preservation and proper spread of Korean food culture, and for K-food to be enjoyed by people around the world.

To increase domestic economic and cultural capital through the growth of K-food, we must effectively apply the four evolutionary types of global cuisine and global food to their respective ingredients, dishes, and food products.

In terms of ingredients, we need to develop strategies to specialize Korean agricultural and marine products, such as Korean seaweed, in local cuisine.

…The origin of the ‘ingredients’ listed on the packaging of K-food sold domestically and overseas is multinational.

This is the dark shadow cast over the global spread of K-food.

―From "Epilogue: Korean Food Evolving into Global Cuisine and Global Food" (p. 342)

There is an abundance of video content showing people consuming, making, and eating K-food.

In response, Koreans pour out their own opinions and even criticisms that go beyond criticism.

…If we want K-food to spread globally, Koreans themselves must make an effort to avoid falling into ‘food nationalism.’

'Food nationalism' refers to the phenomenon in which nationalism between existing nations and countries is projected onto food during the process of European integration.

There is also a hidden industrial intention to ensure that the country's cuisine and food have a monopoly position in the global food distribution system.

―From "Epilogue: Korean Food Evolving into Global Cuisine and Global Food" (p. 343)

When and how did global food enter the Korean Peninsula?

―Global Food in Korean Food History

This book covers the Korean history of global foods that Koreans naturally eat and drink, including whiskey, ice cream, chocolate, pizza, curry, milk, bread, tea, and spices, even though they are not native to Korea.

With the migration of people since ancient times, food ingredients and foods have also spread around the world, and this globalization of food has influenced the society and culture of each country, creating 'global food.'

There are already numerous global foods on the Korean table.

Chili peppers have been localized for a very long time and have become an indispensable ingredient in Korean food. Fruits such as bananas and oranges, as well as foreign snacks and sauces, can be easily found, and foods such as ramen, chicken, and pizza have been 'Koreanized' to capture the taste buds of people not only in Korea but also around the world.

When and how did these global foods, which have so profoundly transformed Korean diets and food culture, arrive on the Korean Peninsula? Professor Joo Young-ha, the author of this book, explains, "Just as no culture in the world has survived untouched by its surroundings, food is no exception. Therefore, Korean food is also a product of exchange and hybridization." He examines the history of global foods across eight distinct periods in Korean history.

The period is the Three Kingdoms period when Buddhist culture was introduced from China, the Goryeo Dynasty under the influence of the Mongol Empire and the Yuan Dynasty, the era of the Columbian Exchange when American crops were transported around the world, the late Joseon Dynasty when exchanges with China and Japan were active, the period of port opening and colonial rule when foreign foods were introduced in earnest, the period after the Korean War and liberation when Korea had to rely on aid from the United States and the United Nations, the compressed growth period when the food industry grew significantly, and the post-globalization period when American-style fast food restaurants appeared and Korean food began to spread around the world.

Nine global foods tell the story of their origins, their arrival on the Korean Peninsula, their "Koreanization," and the reactions and social impact of contemporary people who encountered them, all based on rich literature and images.

By introducing the Korean history of foreign foods, which could easily have become a blank space in world history and Korean history, we propose another perspective on Korean food culture.

Of course, some of the ingredients in food considered 'traditional Korean food' originate from other countries.

The cabbage used in Korean kimchi originated from seeds brought by Chinese immigrants from Shandong Province, China in the early 20th century.

Chili peppers were also brought to the Korean Peninsula from Central America on European ships about 500 years ago, after going through many twists and turns, and cultivation began there.

Foods that are leading the globalization of Korean food today, such as chicken, dakgalbi, and tteokbokki, first appeared in the 1960s.

The chicken was created by combining soybean oil extracted from American soybeans, soybean meal, and American wheat flour.

The slide cheese used in dakgalbi and tteokbokki since the 2010s is also an industrial cheese developed in the United States.

―From the Prologue (page 13)

About 100 years after the end of the war known as the Imjin War, new crops such as peppers, pumpkins, corn, and potatoes were growing in Joseon.

Their origin is the American continent.

These crops, loaded onto Portuguese and Spanish trading ships, crossed the Atlantic Ocean to Europe, and then traveled through the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia to arrive on the Korean Peninsula.

The chili peppers covered in this book also entered the Korean Peninsula in this way and became an indispensable seasoning in cooking since the mid-18th century.

The exchange of goods between the American and Eurasian continents after 1492 is called the 'Columbus Exchange', and the red color and spicy flavor that have become symbols of Korean food today are the results of the Columbian Exchange.

―From the Prologue (page 16)

2.

The past 100 years of Korean life captured in global food

―The taste and memories of food that all generations read and share together.

Excluding agricultural products that were introduced to the Korean Peninsula a long time ago and made cultivation possible, most of the global foods that Koreans enjoy in their daily lives today do not have a long history.

Moreover, Korean society, which has experienced rapid changes over the past 100 years such as colonization, war, economic growth, and globalization, is home to multiple generations with different experiences.

So, individual experiences and perceptions of global food may differ.

In other words, each global food covered in this book embodies the changing face of Korean society, while also reflecting the lives of everyone who has lived through that change.

The history of whiskey, which officially entered the Korean Peninsula in 1882 with the signing of the Treaty of Amity and Commerce between Korea and the United States, includes stories of Korean whiskey that are as exciting as the birthplace of whiskey, including 'Hanyang Sanghoe', which first directly imported whiskey during the Korean Empire, 'Modern Boy' who enjoyed whiskey at a 'cafe' in Gyeongseong, 'pseudo-whiskey' produced from the colonial period to after liberation and various crimes that resulted from it, whiskey made by the Korean government to provide to soldiers, and Korea's 'bomb shot' culture of mixing liquor and beer.

Although the history of ice is so long that ice storage facilities have been built since the Silla Dynasty, ice cream was introduced to the Korean Peninsula through modern Japan.

It brings back sweet memories of ice cream, including the ice cream sold on the streets after the Korean War, the Samgang Hard that was released when factory production began in the 1960s, the popularity of Bravocon and Nuga Bar in the 1970s, and the story of the Korean ice cream industry expanding into the world.

Chocolate is a global food that reminds Koreans of the pain and hunger of war, when they cried out “Give me chocolate” to the UN forces.

However, through the pursuit of the fantasy of chocolate while celebrating Valentine's Day during the compressed growth period, we can also see the conflicting images of chocolate as exploitation and enjoyment in the history of the Korean Peninsula.

In Korea, where bread is not a staple food, the history of bread is special.

Nowadays, handmade bread made with good ingredients is attracting attention, rather than the factory-made bread sold in supermarkets.

However, the reality is that franchises run by large corporations still dominate the Korean bakery industry.

Here, we will tell the story of bread introduced to the Korean Peninsula from Japan in the late 19th century, as well as how mass-produced factory bread spread throughout Korean society after liberation in keeping with the times.

In addition, there are many stories about global foods, such as the milk that children had to drink every day to grow up healthy, the curry udon that they were forced to eat due to the mixed meal promotion movement, the green tea that was shunned as “water made with boiled shiitake mushrooms,” and the first pizza restaurant and American fast food restaurant in Korea.

The author suggests that this book be a catalyst for engaging in 'food chat' with family, friends, colleagues, and neighbors.

The global food experience shared by individuals and communities will become another record, further enriching the history of Korean food culture.

As the demand for whiskey increased and the supply from US military bases became scarce, Japanese whiskey was smuggled in.

Among Japanese whiskies, 'Torys Whiskey' made by Suntory was popular.

…As demand for whiskey increased, some manufacturers even began manufacturing similar products.

At the current 'International Brewery' in Toseong-dong, Seo-gu, Busan, a similar product to Tory's whiskey was manufactured and sold.

The name of this distillery's whiskey was 'Doris', not 'Torys'.

… but Doris Whiskey was a whiskey in name only, without a single drop of whiskey essence.

―From “Whiskey: A World Where Counterfeit Whiskey Runs Wild” (pp. 54-56)

After the war, the number of stores selling 'ice cakes' frozen with ammonia increased rapidly in cities across the country, including Seoul.

At that time, ice cream was a frozen block of ice made by putting red bean paste in sugar water with yellow coloring and sticking it on a wooden skewer.

… The names of representative ice creams sold in Seoul in the 1950s were ‘Seokbinggo’ and ‘Angko.’

Boys from poor families ran through the alleys shouting, carrying buckets of ice cream.

The front of the city's theaters and schools where sports days were held were also good places to sell ice cream.

But hygiene was still a problem.

At that time, ice cream was considered a junk food.

―From “Ice Cream: The Sweet and Cold Flavor That Soothed the Korean Peninsula’s Heat” (p. 88)

For Koreans who experienced the Korean War, chocolate was a delicious and novel food, but it did not remain as a solely positive memory.

A Korean born in the 1940s who experienced such dire poverty that he had no choice but to shout “Give me chocolate” to American soldiers.

They played a leading role in trade as the 'Chocolate English Generation' during the economic development of the Park Chung-hee regime in the 1960s.

… So, they would have been even more determined to ‘live well’ even under dictatorship and oppression.

―From “Chocolate: The Country That Shouted “Give Me Chocolate”” (pp. 113, 114)

We cannot say that all the bread that Koreans ate in the 1960s and 1970s was mass-produced.

At that time, there was always a famous bakery in the center of any city, including Seoul.

In particular, the number of privately run bakeries increased rapidly in the 1960s when the government stepped in to promote snacks.

At that time, almost two-thirds of the bakery names were Japanese names such as ‘○○dang’ or ‘○○sa.’

The influence of the bakeries run by Japanese residents during the colonial period continued until the 1960s.

… bakeries that opened after the mid-1950s were named after Western countries or cities.

German bakery, New York bakery, New Chicago, etc.

It was a result of Western influence intervening in the bread industry after the Korean War.

As bakery names like 'Germany' or 'New York' suggest, names of prosperous regions in the West also attracted consumers' attention.

―From “Why Bread is Expensive in Korea” (pp. 243, 244)

3.

K-Food's Advancement to Global Food: What's the Future?

―A vision for K-food proposed by food humanist Professor Joo Young-ha

Just as countless global foods entered the Korean Peninsula and underwent a process of Koreanization, Korean food, as it spreads around the world, will also undergo a process of localization in each region.

In this book, the author not only tells the history of global foods that have entered the Korean Peninsula, but also examines the current state of K-food, which is gaining global attention.

The book's epilogue examines the evolution of specific regional foods and food products into global foods by type, and by applying examples such as kimchi, ramen, and seaweed, it captures the transformation of K-food into global foods.

In addition, it does not miss the critical view of the "food nationalism" that blindly criticizes the way people around the world consume K-food differently from Koreans, who are only concerned with the amount of food exported without any consideration for the preservation of Korea's unique food culture, and the mass production system of the global distribution network that is accelerating the climate crisis.

This perspective on K-food as a global food presents a vision for the preservation and proper spread of Korean food culture, and for K-food to be enjoyed by people around the world.

To increase domestic economic and cultural capital through the growth of K-food, we must effectively apply the four evolutionary types of global cuisine and global food to their respective ingredients, dishes, and food products.

In terms of ingredients, we need to develop strategies to specialize Korean agricultural and marine products, such as Korean seaweed, in local cuisine.

…The origin of the ‘ingredients’ listed on the packaging of K-food sold domestically and overseas is multinational.

This is the dark shadow cast over the global spread of K-food.

―From "Epilogue: Korean Food Evolving into Global Cuisine and Global Food" (p. 342)

There is an abundance of video content showing people consuming, making, and eating K-food.

In response, Koreans pour out their own opinions and even criticisms that go beyond criticism.

…If we want K-food to spread globally, Koreans themselves must make an effort to avoid falling into ‘food nationalism.’

'Food nationalism' refers to the phenomenon in which nationalism between existing nations and countries is projected onto food during the process of European integration.

There is also a hidden industrial intention to ensure that the country's cuisine and food have a monopoly position in the global food distribution system.

―From "Epilogue: Korean Food Evolving into Global Cuisine and Global Food" (p. 343)

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: October 16, 2023

- Page count, weight, size: 368 pages | 135*200*30mm

- ISBN13: 9791170870593

- ISBN10: 1170870597

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)