After the square

|

Description

Book Introduction

On December 3, 2024, the plaza was once again opened to the public due to the unprecedented events of martial law and the impeachment of the president.

Where did the citizens of this square come from, and where are they going now? "After the Square" is part of an effort to transcend the divisions of "us" and "them" and the conflict between progressives and conservatives, and to examine more closely the dynamics of those who were active both inside and outside the square.

By bringing together the writings of four authors—Shin Jin-wook, a sociologist who studies civil society and democracy; Lee Seung-yoon, a social welfare scholar and field researcher in the field of labor; Yang Seung-hoon, a sociologist who studies regional industrial structures with an interest in the youth labor market; and Lee Jae-jeong, a researcher of precarious labor and social welfare and active as a representative of several social movement organizations—we examine the main actors of the December 3rd Square in a three-dimensional manner, from those who created it to those who were erased from it.

This book's historical and timely analysis of political actors in civil society, including the Asphalt Far Right, the women of the Namtaeryeong rally, men in their 20s and 30s, and young unstable workers, is centered around the "square," firmly supporting the book's aim to view the December 3rd Square from a three-dimensional perspective.

'Plaza,' 'society,' and 'politics' are not separate entities, and democracy can function healthily only when we continuously imagine and invent new plazas, new societies, and new politics together with diverse citizens.

I hope this book can create a small crack in the wall that divides citizens and politics, inside and outside the square.

Where did the citizens of this square come from, and where are they going now? "After the Square" is part of an effort to transcend the divisions of "us" and "them" and the conflict between progressives and conservatives, and to examine more closely the dynamics of those who were active both inside and outside the square.

By bringing together the writings of four authors—Shin Jin-wook, a sociologist who studies civil society and democracy; Lee Seung-yoon, a social welfare scholar and field researcher in the field of labor; Yang Seung-hoon, a sociologist who studies regional industrial structures with an interest in the youth labor market; and Lee Jae-jeong, a researcher of precarious labor and social welfare and active as a representative of several social movement organizations—we examine the main actors of the December 3rd Square in a three-dimensional manner, from those who created it to those who were erased from it.

This book's historical and timely analysis of political actors in civil society, including the Asphalt Far Right, the women of the Namtaeryeong rally, men in their 20s and 30s, and young unstable workers, is centered around the "square," firmly supporting the book's aim to view the December 3rd Square from a three-dimensional perspective.

'Plaza,' 'society,' and 'politics' are not separate entities, and democracy can function healthily only when we continuously imagine and invent new plazas, new societies, and new politics together with diverse citizens.

I hope this book can create a small crack in the wall that divides citizens and politics, inside and outside the square.

index

Introduction - From the Tragedy of Civil War to the Restoration of Democracy

Chapter 1: The Crisis of Korean Democracy and Far-Right Fascism | Shin Jin-wook

Chapter 2: The Plaza Asks, Youth Answers - Remaking the World, Remembering the Democracy of the Plaza | Lee Jae-jung

Chapter 3: The 2030 Male Frame War: The Cheerleading Stick They Don't Have | Yang Seung-hoon

Chapter 4: Melting Labor, Youth Finding Solidarity | Seungyoon Lee

main

Chapter 1: The Crisis of Korean Democracy and Far-Right Fascism | Shin Jin-wook

Chapter 2: The Plaza Asks, Youth Answers - Remaking the World, Remembering the Democracy of the Plaza | Lee Jae-jung

Chapter 3: The 2030 Male Frame War: The Cheerleading Stick They Don't Have | Yang Seung-hoon

Chapter 4: Melting Labor, Youth Finding Solidarity | Seungyoon Lee

main

Detailed image

Into the book

The annual report of the Institute for Democracy and Diversity, published in April 2024, contained a chilling warning that South Korea was the only developed democracy undergoing serious authoritarianism, and that countries like Hungary were already showing this pattern a decade ago, before they became full-blown authoritarian regimes.

What was most concerning was the fact that the drop in Korea's democracy index and status was too large.

--- From "Chapter 1: The Crisis of Korean Democracy and Far-Right Fascism"

Despite the success of citizens and constitutional institutions in preventing the illegal martial law and initiating the impeachment trial process, the mere fact that a military-mobilized coup attempt occurred has fatally damaged not only the evaluation of Korean democracy but also the image of Korean society.

(…) Martial law was lifted and the president was impeached.

But the very fact that it is a 'country where a coup d'état can occur' has serious implications.

In other words, the fact that even today, 38 years after 1987, Korean democracy is very fragile and not at all 'solid' is a major alarm bell.

--- From "Chapter 1: The Crisis of Korean Democracy and Far-Right Fascism"

Korean society cannot return to the state before December 3rd.

How can we create a world "beyond December 3rd" that is fundamentally different from the Korean society of the past that fostered and permitted all this state and social violence? That is the most crucial question and choice we have left.

--- From "Chapter 1: The Crisis of Korean Democracy and Far-Right Fascism"

Looking at the economic inequality category, 92.3% of respondents pointed out the deepening economic inequality as a crisis of democracy, and 59.3% of the youth in the square chose 'resolving economic inequality and ensuring equal opportunity' as the most important measure for strengthening democracy.

This demonstrates the recognition that economic inequality goes beyond simple income disparities, livelihood insecurity, and differences in opportunity to undermine the foundations of democracy through imbalances in social status, political participation, and limited voice.

We can also see a sense of crisis that we must resolve the problem of economic inequality to move toward true democracy.

The issue of economic inequality is particularly important for the younger generation, as the frustration that "no matter how hard you try, things don't get better" can lead to distrust of the public system or political cynicism.

--- From "Chapter 2: The Square Asks and the Youth Answers"

The experience of struggling together during the particularly cold winter connected them and made it impossible for them to ignore each other any longer.

At the end of the march, when a farmer encouraged them by saying, “Our daughters have worked hard,” another citizen said, “They are not daughters, they are non-binary,” and the farmer responded, “I will keep that in mind.” This anecdote shows that the space was a place where political recognition of the existence of minorities and acceptance of their identities took place.

--- From "Chapter 2: The Square Asks and the Youth Answers"

The fact that this kind of square experience feels new to the younger generation is also related to their upbringing.

For young adults who spent their adolescence or young adulthood between 2020 and 2023, the period when they should have been actively interacting with the outside world, they experienced social isolation through 'social distancing' to prevent infectious diseases, so it is inevitable that they will feel unfamiliar with closely connecting with others in a wide space.

Moreover, many of them either have trauma regarding group action due to the Sewol Ferry disaster during their youth or never had the opportunity to do so in the first place.

For these people, the sense of connection that a large plaza provides is an unfamiliar but refreshing experience.

--- From "Chapter 2: The Square Asks and the Youth Answers"

Their ideology is still more flexible and unfixed than what the media or politicians define it to be.

Therefore, we must approach this situation with the awareness that the established progressive political forces have failed to persuade and organize men in their 20s and 30s, nor have they addressed their grievances.

In other words, rather than asking whether men in their 20s and 30s have become conservative, we should be asking whether progressive political forces have responded appropriately to men in their 20s and 30s.

At the heart of it all is the issue of political space for men in their 20s and 30s.

--- From "Chapter 3: The 2030 Male Frame War"

A male college student in his 20s whom I recently met in the area explained his reason for not participating in the pro-impeachment rally by saying, “Why are we coming out when they don’t give us cheering sticks?”

The cheering stick symbolizes a ticket to participate in plaza politics.

For men in their 20s and 30s, the cheering stick symbolizes two things.

First, it gives political power, and second, it requires a clear agenda as a driving force for actual participation.

However, in a situation where there is no authority or an agenda to motivate them, they remain passive and only maintain the status quo.

On the other hand, women in their 20s and 30s have become self-reliant through the aforementioned 10-year feminist reboot and the impeachment protests of 2016-2017.

And they have been embedding their agenda into progressive discourse and common sense among politicians.

--- From "Chapter 3: The 2030 Male Frame War"

Many studies have pointed out that these experiences of unstable labor are closely linked to political consciousness and attitudes toward institutional politics.

For example, the European Union's Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions (Eurofound) reported that young people experiencing precarious work are more likely to withhold support from traditional political parties or be more actively mobilized in one-off issue campaigns or anti-establishment movements.

Precarious workers are vulnerable to social and economic crises and tend to favor public interventions such as redistribution policies and welfare expansion. However, when these demands are frustrated, they also express distrust of the overall political system.

As evidenced by the Spanish 'Indignados' movement and the Italian youth's resistance to platform work, young people in precarious employment are likely to use their material insecurity as a direct driving force for radical and collective action.

--- From "Chapter 4: Labor Melting, Youth Finding Solidarity Difficult"

However, it has not yet been empirically established that the unstable employment of Korean youth directly leads to a specific political orientation, such as the far right or radical left.

As I have repeatedly argued throughout this article, further research is needed to determine which political landscape (left or right) the growing structural distrust will ultimately lead to.

Currently, both paths of ‘structural distrust → political apathy’ or ‘structural distrust → radicalization’ are observed among young people in unstable employment, and it is too early to determine which path is dominant.

This is an issue that needs to be thoroughly investigated through future long-term follow-up studies or microscopic and qualitative research.

What was most concerning was the fact that the drop in Korea's democracy index and status was too large.

--- From "Chapter 1: The Crisis of Korean Democracy and Far-Right Fascism"

Despite the success of citizens and constitutional institutions in preventing the illegal martial law and initiating the impeachment trial process, the mere fact that a military-mobilized coup attempt occurred has fatally damaged not only the evaluation of Korean democracy but also the image of Korean society.

(…) Martial law was lifted and the president was impeached.

But the very fact that it is a 'country where a coup d'état can occur' has serious implications.

In other words, the fact that even today, 38 years after 1987, Korean democracy is very fragile and not at all 'solid' is a major alarm bell.

--- From "Chapter 1: The Crisis of Korean Democracy and Far-Right Fascism"

Korean society cannot return to the state before December 3rd.

How can we create a world "beyond December 3rd" that is fundamentally different from the Korean society of the past that fostered and permitted all this state and social violence? That is the most crucial question and choice we have left.

--- From "Chapter 1: The Crisis of Korean Democracy and Far-Right Fascism"

Looking at the economic inequality category, 92.3% of respondents pointed out the deepening economic inequality as a crisis of democracy, and 59.3% of the youth in the square chose 'resolving economic inequality and ensuring equal opportunity' as the most important measure for strengthening democracy.

This demonstrates the recognition that economic inequality goes beyond simple income disparities, livelihood insecurity, and differences in opportunity to undermine the foundations of democracy through imbalances in social status, political participation, and limited voice.

We can also see a sense of crisis that we must resolve the problem of economic inequality to move toward true democracy.

The issue of economic inequality is particularly important for the younger generation, as the frustration that "no matter how hard you try, things don't get better" can lead to distrust of the public system or political cynicism.

--- From "Chapter 2: The Square Asks and the Youth Answers"

The experience of struggling together during the particularly cold winter connected them and made it impossible for them to ignore each other any longer.

At the end of the march, when a farmer encouraged them by saying, “Our daughters have worked hard,” another citizen said, “They are not daughters, they are non-binary,” and the farmer responded, “I will keep that in mind.” This anecdote shows that the space was a place where political recognition of the existence of minorities and acceptance of their identities took place.

--- From "Chapter 2: The Square Asks and the Youth Answers"

The fact that this kind of square experience feels new to the younger generation is also related to their upbringing.

For young adults who spent their adolescence or young adulthood between 2020 and 2023, the period when they should have been actively interacting with the outside world, they experienced social isolation through 'social distancing' to prevent infectious diseases, so it is inevitable that they will feel unfamiliar with closely connecting with others in a wide space.

Moreover, many of them either have trauma regarding group action due to the Sewol Ferry disaster during their youth or never had the opportunity to do so in the first place.

For these people, the sense of connection that a large plaza provides is an unfamiliar but refreshing experience.

--- From "Chapter 2: The Square Asks and the Youth Answers"

Their ideology is still more flexible and unfixed than what the media or politicians define it to be.

Therefore, we must approach this situation with the awareness that the established progressive political forces have failed to persuade and organize men in their 20s and 30s, nor have they addressed their grievances.

In other words, rather than asking whether men in their 20s and 30s have become conservative, we should be asking whether progressive political forces have responded appropriately to men in their 20s and 30s.

At the heart of it all is the issue of political space for men in their 20s and 30s.

--- From "Chapter 3: The 2030 Male Frame War"

A male college student in his 20s whom I recently met in the area explained his reason for not participating in the pro-impeachment rally by saying, “Why are we coming out when they don’t give us cheering sticks?”

The cheering stick symbolizes a ticket to participate in plaza politics.

For men in their 20s and 30s, the cheering stick symbolizes two things.

First, it gives political power, and second, it requires a clear agenda as a driving force for actual participation.

However, in a situation where there is no authority or an agenda to motivate them, they remain passive and only maintain the status quo.

On the other hand, women in their 20s and 30s have become self-reliant through the aforementioned 10-year feminist reboot and the impeachment protests of 2016-2017.

And they have been embedding their agenda into progressive discourse and common sense among politicians.

--- From "Chapter 3: The 2030 Male Frame War"

Many studies have pointed out that these experiences of unstable labor are closely linked to political consciousness and attitudes toward institutional politics.

For example, the European Union's Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions (Eurofound) reported that young people experiencing precarious work are more likely to withhold support from traditional political parties or be more actively mobilized in one-off issue campaigns or anti-establishment movements.

Precarious workers are vulnerable to social and economic crises and tend to favor public interventions such as redistribution policies and welfare expansion. However, when these demands are frustrated, they also express distrust of the overall political system.

As evidenced by the Spanish 'Indignados' movement and the Italian youth's resistance to platform work, young people in precarious employment are likely to use their material insecurity as a direct driving force for radical and collective action.

--- From "Chapter 4: Labor Melting, Youth Finding Solidarity Difficult"

However, it has not yet been empirically established that the unstable employment of Korean youth directly leads to a specific political orientation, such as the far right or radical left.

As I have repeatedly argued throughout this article, further research is needed to determine which political landscape (left or right) the growing structural distrust will ultimately lead to.

Currently, both paths of ‘structural distrust → political apathy’ or ‘structural distrust → radicalization’ are observed among young people in unstable employment, and it is too early to determine which path is dominant.

This is an issue that needs to be thoroughly investigated through future long-term follow-up studies or microscopic and qualitative research.

.

--- From "Chapter 4: Labor Melting, Youth Finding Solidarity Difficult"

--- From "Chapter 4: Labor Melting, Youth Finding Solidarity Difficult"

Publisher's Review

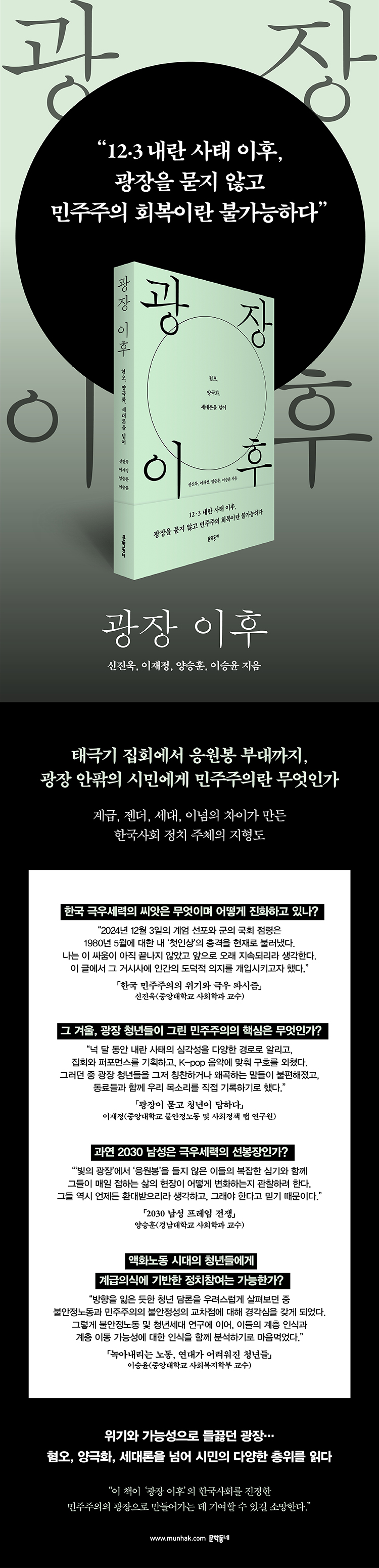

From Taegeukgi rallies to cheering stick units,

What does democracy mean to citizens inside and outside the square?

Differences in class, gender, generation, and ideology created

Topography of political actors in Korean society

Where do the citizens of the square come from and where do they go?

The Faces of Democracy Revealed by the December 3 Martial Law

At 10:27 PM on December 3, 2024, martial law was declared in South Korea, something no one dared to imagine would happen today.

Politicians and citizens flocked to the National Assembly in response to the sudden martial law that broke into their living spaces, and they successfully lifted martial law within two hours by blocking the intrusion of the military mobilized for martial law.

This incident alone was a huge shock, but with the announcement of the impeachment of the leader of the rebellion, Korean society was shocked to see how many powerful groups were involved in this rebellion, and spent four months in turmoil, both together and in conflict, in squares formed across the country.

On the surface, the square appeared to be divided into two groups: those in favor of and those against the impeachment of Yoon Seok-yeol.

While the citizens of the former expressed their various aspirations and demands by painting Yeouido, Gwanghwamun, Namtaeryeong, and Hangangjin with colorful cheering sticks, the citizens of the latter shouted for the legitimacy of martial law and protected Yoon Seok-yeol, holding the Taegeukgi and the American flag and raising theories of election fraud and Chinese involvement.

Where did the citizens of this square come from, and where are they going now? "After the Square" is part of an effort to transcend the divisions of "us" and "them" and the conflict between progressives and conservatives, and to examine more closely the dynamics of those who were active both inside and outside the square.

By bringing together the writings of four authors—Shin Jin-wook, a sociologist who studies civil society and democracy; Lee Seung-yoon, a social welfare scholar and field researcher in the field of labor; Yang Seung-hoon, a sociologist who studies regional industrial structures with an interest in the youth labor market; and Lee Jae-jeong, a researcher of precarious labor and social welfare and active as a representative of several social movement organizations—we examine the main actors of the December 3rd Square in a three-dimensional manner, from those who created it to those who were erased from it.

"After the Square" provides a comprehensive overview of the political participation of citizens, including the far-right forces and cheering stick units that seemed to divide the square, and analyzes in greater detail how the far-right forces in Korea have historically changed (Shin Jin-wook) and what kind of democracy the youth in the square desire (Lee Jae-jung).

Afterwards, we examine the discourse of 'the extreme right-wing shift of men in their 20s and 30s' that emerged in contrast to the heated political participation of young women in their 20s and 30s (Yang Seung-hoon), and conclude by forecasting how this instability may affect political consciousness based on the results of an empirical study on the labor instability of the youth generation (Lee Seung-yoon).

This book's historical and timely analysis of political actors in civil society, including the Asphalt Far Right, the women of the Namtaeryeong rally, men in their 20s and 30s, and young unstable workers, is centered around the "square," firmly supporting the book's aim to view the December 3rd Square from a three-dimensional perspective.

The stories of the citizens who filled the Democracy Square, including youth, women, workers, and minorities, who were the main players in the square that was opened wide by martial law and impeachment, continue to be recorded.

In addition to this trend, "After the Square" critically examines the history of the citizens who create the dynamism of the square, or the citizens who do not show their faces in the square, and what they think and feel.

This is an effort to accurately understand the issues of democracy that are divided, combined, and formed according to political inclinations, ideologies, values, class, gender, generation, and ideology. It will serve as a welcome gift to readers seeking the driving force for the restoration and development of democracy after the 12?3 incident in 『After the Square』, leading them to a forum for discussion.

“The tragedy of which Marx speaks, that is, the social upheaval that brings with it immense human suffering, (…) at first passes like a short farce, but then returns as a true tragedy.

In the failed Munich beer hall coup of 1923, Adolf Hitler appeared to be nothing more than an anachronistic insurrectionist, but in 1933, as Führer, he abolished the Weimar Republic and established a Nazi dictatorship.

“If December 3rd is not to become a harbinger of such a tragedy, we must seriously reflect on December 3rd and transform ourselves and society.” (p. 9)

Far-right forces, cheering stick troops, men in their 20s and 30s, the unstable youth generation…

Restoring democracy is impossible without asking the public for a square.

Now that the "December 3rd Square" has closed and all eyes are on the early presidential election, what pressing issues in Korean society must be addressed? Before the heat of the square is swept away by the political wave, "After the Square" seeks to answer the following questions: △ How has the far-right evolved, and how destructive is it? △ What is the background of young women's political participation and solidarity? △ Have young men in their 20s and 30s actually become far-right? △ What impact does unstable youth employment have on their political awareness? △ What material conditions do young people inside and outside the square face? △ What kind of democracy do young people in the square ultimately desire?

· "The Crisis of Korean Democracy and Far-Right Fascism" _ Shin Jin-wook

: What are the seeds of Korea's far-right forces, and how are they evolving?

Sociologist Shin Jin-wook opens this book with the shocking declaration that the December 3 coup, which occurred amidst the global trend of democratic decline, was a decisive event that exposed the crisis of Korean democracy, and that the evolution of far-right forces that advocate anti-communism, anti-North Korea, anti-China, anti-feminism, and anti-homosexuality is a "sign of fascism."

The political consciousness of Korean citizens is attracting global attention.

In particular, the candlelight citizens who led the protests to impeach President Park Geun-hye in 2017 were recorded as the main players in the victory that prevented the regression of democracy.

However, the December 3 martial law that occurred seven years later forced us to reflect on the current state of Korean democracy and to realize that even a country like South Korea, which was considered to have achieved advanced democracy, could fall into dictatorship.

Moreover, the fact that this civil war was a coup d'état by a democratically elected president who destroyed his own legitimacy has decisively proven that "solid democracy" is close to an illusion.

When the Western District Court issued an arrest warrant for Yoon Seok-yeol, who was accused of being the leader of a rebellion, the coup forces, having lost their institutional power base, continuously called the far-right forces "the people" in an attempt to build a base of popular support.

This combination of extreme right-wing power and the masses led to the incident of rioting and breaking into the Western District Court, clearly revealing signs of fascism. According to the author, this can be said to be the fifth stage of Robert Paxton's six stages of fascism, where fascist tendencies enter the political system.

In other words, the violent incidents by far-right forces over the past four months and the conservative party's acquiescence and support were serious incidents that showed that fascism had developed to a considerable degree in Korean society.

Shin Jin-wook asserts that although the impeachment of Yoon Seok-yeol halted the development of fascism, the far-right's activities were not temporary or impulsive.

The far-right power elite organizations, mass communities, and some of those with far-right beliefs that have been built over a long period since democratization have only become visible in this impeachment situation.

As can be seen in the graph in Chapter 1 of this book (see page 45), over the past 20 years, the participation rate of those who are “very conservative” in Korean society has been similar to that of those who are “very progressive” since 2019, but has surpassed that of “very progressive” since the recent impeachment rally.

Therefore, we must not forget that even though the far-right movement appears to have temporarily stalled in the wake of the early presidential election held immediately following the impeachment of Yoon Seok-yeol, it can be politically reactivated at any time if the opportunity arises.

“If you thought that the cruel slogans like ‘punish,’ ‘kill,’ and ‘tread on’ that appeared at the protests opposing the impeachment of President Yoon Seok-yeol were merely a hysterical reaction of conservatives facing the threat of impeachment and a change of government, you would be mistaken.

(…) Many people have become accustomed to calling themselves ‘right-wing’ and, through their hostility toward the ‘left,’ dividing ‘us’ and ‘them,’ and objectifying ‘them’ as ‘enemies’ of the Republic of Korea, ‘non-citizens’ who must be expelled, and ‘inhumans’ who can be eliminated.” (p. 60)

In particular, the author points out that far-right forces can pose a significant threat to democracy as they become increasingly radical in their language and actions, centered around hatred for specific targets.

In this impeachment situation, we have experienced a situation where “state violence that destroys someone’s dignity can be committed with the consent and participation of other members of society.”

The author worries that if the combination of the conservative party and the asphalt right is dismissed as a mere "farce," we may be facing a much greater "tragedy" in the future.

At the same time, he emphasizes that rather than simply viewing the current reality as a dichotomy of whether it is fascism or not, we must look at the 'entire process by which fascism was born and grew.'

A precise understanding of the ever-changing and evolving far-right forces is essential to “responding to the vulnerabilities of Korean democracy and building a stronger defense wall for democracy and human rights.”

· "The Square Asks, the Youth Answers" _Lee Jae-jeong

: What was the core of democracy that the youth of the square drew that winter?

As a researcher and activist, Lee Jae-jeong took the plaza as a site in 2024 and recorded its voices and ultimate aspirations.

Based on an online survey conducted by the Youth for Yoon Seok-yeol's Resignation (hereafter, Youth for Yoon Seok-yeol's Resignation) for approximately 1,000 young people who took to the plaza for about two weeks in January 2025, the author "collected in a multi-layered manner the motivations for participation, memorable scenes, perception of the crisis of democracy, and imagination of future society of the young people who participated in this plaza rally," quantified it, and worked to elucidate its meaning.

The background of this survey is the regret that “our stories standing in the square are not being drawn by our own hands.”

The older generation's response of praising the 'MZ generation' for their dedication to protecting democracy as 'admirable' and 'admirable' reveals, on the one hand, an underlying perception that does not recognize young people as 'full citizens'. In response, the young people themselves sought to understand the demands of the young people standing in the democratic square and connect them to political participation activities.

This plaza was attended by many young people who had experience participating in the Park Geun-hye impeachment rally, the gender equality movement, the climate crisis response movement, and rallies related to social disasters. They were feeling angry at the Yoon Seok-yeol administration, which is clearly responsible for the Itaewon tragedy, the death of Chae Sang-byeong, and the KAIST student “silencing” incident, and they came to the plaza with a “desperate feeling that there is no place left to retreat.”

As the declaration continued on social media, young people “were always in the square,” and citizens who wanted to protect democracy learned from each other in the square and raised political awareness.

When asked what factors threaten democracy, young people cited 'concentration and abuse of power' and 'widening economic inequality' as the main threats.

Considering that in 2017, the square was primarily focused on political issues such as abuse of state power and prosecutorial reform, addressing economic inequality appears to be a new agenda.

A closer look at the content reveals that the youth point out that “differences in class, gender, education, region of origin, and upbringing within the younger generation are leading to social disparities.”

These responses from young people suggest that resolving economic polarization is an essential element of democracy, and that the political world must seriously embrace this demand.

He also responded that while 'investigating and punishing those responsible for crimes of sedition' is important as a way to restore democracy, 'solving social problems through social reform' is equally important.

Although this impeachment rally became a hot topic due to its cheerful protest grammar, including cheering sticks, K-pop, and flags, the youth came to the square not only with a desire to eliminate the structural absurdity that made this civil war possible, but also with a desire for fundamental reform that would eliminate inequality and discrimination.

Today's young people experience inequality and the collapse of the social ladder in all aspects of their lives, including education, housing, assets, and labor.

As public criticism of President Yoon Seok-yeol grew, the youth unemployment rate rose sharply, from 4.1% in August 2024 to 7.5% in March 2025.

(…) In order to guarantee the free political decision-making of the younger generation, it is necessary to resolve the economic gap problem so that they can achieve a substantial improvement in their abilities, and to create a channel where young people of various classes, genders, educational backgrounds, regions, and social statuses can participate in the political decision-making process and have their voices heard in a comprehensive manner.

(Pages 97-98)

Above all, this plaza was different from the previous ones in that it was a space of hospitality where people could learn from each other and share.

Lee Jae-jung emphasized solidarity, care, and community as the message the plaza of 2024 left for our society.

Citizens in the square became accustomed to the unfamiliar grammar of protest, and existing activist groups tried to maintain a culture of equality by looking after and being considerate of one another, such as by reading the declaration of “Everyone’s Promise for an Equal Assembly” and distributing food trucks and hot packs to welcome new faces to the square.

As the youth of the square most envision a future where equality and diversity are respected, Lee Jae-jung concludes this chapter by emphasizing the need to remember and continue the narrative of democracy based on care, solidarity, diversity, and difference in this square.

· "2030 Male Frame War" _ Yang Seung-hoon

: Are men in their 20s and 30s really the vanguard of the far right?

Sociologist Yang Seung-hoon examines the question, “Are men in their 20s and 30s truly politically conservative or far-right?” by connecting it to the public square.

In this impeachment situation, unlike the image of women in their 20s and 30s as progressives, the frame defining men in their 20s and 30s was, above all, ‘extreme right-wing’ or ‘conservative.’

The frame was primarily created based on the gender ratio of the rally participants, and was further strengthened as the faces of male participants were highlighted in events such as the Western District Court riot, the university campus rally, and the provocative actions of the 'New Men's Solidarity.'

The author argues that there is a need to examine society's perspective on men in their 20s and 30s, and attempts a 'fact check on men in their 20s and 30s.'

Yang Seung-hoon points out that the young male population is not homogeneous, that many of them have fluid political leanings and value orientations, and that even if they harbor anti-Chinese and anti-feminist sentiments, they are not extreme right-wingers who threaten to undermine the democratic system.

He then argues that if young men are relatively passive in the social participation arena symbolized by the plaza, the cause is not their conservatism or extreme rightward shift, but rather the contradictions and tensions that arise from the failure to find a “new role model” suited to the changing times in a situation where they have lost “the power as breadwinners enjoyed by their fathers’ generation.”

The '2030 Men' are clearly distinct from the mainstream right wing in Korea, which aims for a wealthy and powerful nation based on anti-communist, anti-North Korea, and anti-union policies.

Unlike the Korean right-wing, which actively opposed the impeachment of Yoon Seok-yeol, more than half of men in their 20s and 30s supported the impeachment.

Even among voters who chose Yoon Seok-yeol in the 2022 presidential election, a series of survey results suggest that they did not show extreme right-wing positions, such as supporting him during the impeachment process.

Although shocking incidents such as the Western District Court riot, the Northwest Youth League, and the New Men's Solidarity have been reported many times, the author argues that it is not true to label the 2030 male group as "extreme right-wing" because "there are only a handful of right-wing extremists causing disturbances among men in their 20s and 30s, and their support among men in their 20s and 30s is minimal," and that it will not help in finding a path for progressive politics in the long term.

According to Yang Seung-hoon, men in their 20s and 30s are ‘swing voters.’

The sentiments of the online community, which is their main activity space, such as “anti-Democratic Party, anti-feminism, pro-Yoon Seok-yeol, second-choice men, etc.”, cannot be a sign of extreme right-wing or conservative tendencies, and they say that “rather than choosing a political party for each election, they have voted based on their values and interests or their evaluation of the government and each political faction.”

Yang Seung-hoon argues that the role of progressive politics is to understand the still-flexible and unstable political orientation and party support tendencies of men in their 20s and 30s, and to persuade and bring them into the political arena.

In conclusion, we argue that “a full-fledged discussion on the creation of a new political space” is necessary, and we add discussions on gender equality in service, pension systems, and family rights as examples of such political space.

“Within Pemco, there is a strong sense of hostility towards the established political forces and the younger generation (especially the 86 generation).

According to sociologist Koo Jeong-woo, Femco is interested in issues where positions are polarized.

They prefer fighting the establishment rather than open hatred or attacks on minorities, and their main emotion is antipathy toward the existing order.

“In other words, although Pemco’s political stance is very unstable, if a political force emerges that can identify their grievances and political desires and deliver a clear message, there is a high possibility that they will quickly unite and take action.” (p. 149)

· "Melting Labor, Youth Finding Solidarity Difficult" _Lee Seung-yoon

: Is class-conscious political participation possible for young people in the era of liquid labor?

Lee Seung-yoon, a social policy researcher, empirically analyzes the material conditions of the lives of young people living outside the public square, and, using overseas examples, examines how their political consciousness can develop.

Lee Seung-yoon distances himself from the simple youth generation theory of “progressive young women, conservative young men” that has spread in the conflict between the pro- and anti-impeachment camps, and instead focuses on the sociological reality in which “various young people with different life trajectories and political consciousness coexist” within the categories of young men and young women.

Starting from Marx's proposition that "existence determines consciousness," Seungyoon Lee proposes a historical materialist approach that views young people not only from ideological and political perspectives such as progressive and conservative, or participants and non-participants in the impeachment rally, but also from a perspective centered on the material foundations of labor and class.

To this end, we derived an instability index by synthesizing three aspects: income, employment type, and social insurance coverage, and analyzed the long-term stratification patterns of the youth (19-34 years old) and non-youth (35-54 years old).

This analysis clearly shows that over the past 20 years, there has been a growing trend of instability, particularly among the younger generation, and a deepening polarization within the generation.

The instability of young people is closely related to the growing trend of “liquefied labor,” a phenomenon in which “the boundaries of labor as we have traditionally understood them are melting away, and the concept of labor as defined by existing legal systems is becoming ambiguous,” such as freelancers, call center workers, platform workers, and young people who alternate between unemployment and employment.

While irregular work in terms of time, form, and employment is on the rise, the current legal system relies on standard employment relationships, leaving workers with high levels of instability vulnerable to various social safety nets. One social group that is particularly acutely affected by this problem is the youth precariat.

The author attempts further analysis by adding a gender axis to this, and what is interesting is that while polarization tends to deepen among both young men and young women, the 'very insecure' group has increased noticeably among young men compared to young women.

In addition, to determine how labor instability affects social perception, we examined 'subjective class perception' and 'attitudes toward the possibility of social mobility'. We found that while both young men and women exhibited a pattern of being more pessimistic about the possibility of upward mobility when objective instability was high, young men exhibited a stronger level of pessimism when faced with the same level of instability.

The author cautiously points out that the analysis results, which show that one in two young men are in "very unstable" working conditions and that young men show more despair than hope in terms of their chances of upward mobility, can provide a clue to understanding various discourses and phenomena in Korean society surrounding men in their 20s and 30s.

The author emphasizes that, rather than hastily judging reality with generational theories, we must advance social solidarity against an unequal social system through active political and social movement practices, as this kind of existential instability can lead to political consciousness that goes in very conflicting directions, such as distrust of institutional politics in general, political resignation, demands for radical left-wing politics, or, conversely, support for far-right populism.

“Not all young people in precarious employment are politically progressive or supportive of systemic change.

Some studies indicate that their disillusionment with the system may lead them to show extreme right-wing tendencies or support populist parties.

“Both the leftist currents demanding expanded redistribution and social rights and the rightist currents expressing resistance to immigration and multicultural policies stem from a common perception of ‘distrust in institutional politics.’” (p. 208)

The crisis and possibility of democracy were both present in the square.

Transcending hate, polarization, and generationalism, we explore the diverse layers of citizenship.

May, when the shock of the night of civil war had not yet subsided.

Among the candidates who have declared their candidacy for the presidential election, some call themselves “candidates of the square,” some are unable to decide on a political stance on the insurrectionists, as if they have forgotten the reason for holding an early presidential election in the first place, and some are boldly revealing anti-China and anti-feminist sentiments by bringing up the 2021 pledge to “abolish the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family.”

Amidst a war of words fueled by half-baked promises, negativity, and hate, we are struggling through a time when political engineering takes precedence over democratic values, as if the unprecedented national emergency had never passed.

Hatred, polarization, and generationalism are just other names for the dangerous standards that divide a society into four.

"After the Square" is the result of focusing on the "citizens of the square" as a starting point for examining the crisis of democracy revealed by the coup d'état and seeking a better future for democracy.

In doing so, the four authors sought to intervene in the discourse that dichotomizes people by gender, generation, faction, and ideology, or generalizes a group as possessing homogeneous and single attributes, and considered ways to realize and sustain the value of diversity that blossomed in the square beyond the square.

'Plaza,' 'society,' and 'politics' are not separate entities, and democracy can function healthily only when we continuously imagine and invent new plazas, new societies, and new politics together with diverse citizens.

I hope this book can create a small crack in the wall that divides citizens and politics, inside and outside the square.

What does democracy mean to citizens inside and outside the square?

Differences in class, gender, generation, and ideology created

Topography of political actors in Korean society

Where do the citizens of the square come from and where do they go?

The Faces of Democracy Revealed by the December 3 Martial Law

At 10:27 PM on December 3, 2024, martial law was declared in South Korea, something no one dared to imagine would happen today.

Politicians and citizens flocked to the National Assembly in response to the sudden martial law that broke into their living spaces, and they successfully lifted martial law within two hours by blocking the intrusion of the military mobilized for martial law.

This incident alone was a huge shock, but with the announcement of the impeachment of the leader of the rebellion, Korean society was shocked to see how many powerful groups were involved in this rebellion, and spent four months in turmoil, both together and in conflict, in squares formed across the country.

On the surface, the square appeared to be divided into two groups: those in favor of and those against the impeachment of Yoon Seok-yeol.

While the citizens of the former expressed their various aspirations and demands by painting Yeouido, Gwanghwamun, Namtaeryeong, and Hangangjin with colorful cheering sticks, the citizens of the latter shouted for the legitimacy of martial law and protected Yoon Seok-yeol, holding the Taegeukgi and the American flag and raising theories of election fraud and Chinese involvement.

Where did the citizens of this square come from, and where are they going now? "After the Square" is part of an effort to transcend the divisions of "us" and "them" and the conflict between progressives and conservatives, and to examine more closely the dynamics of those who were active both inside and outside the square.

By bringing together the writings of four authors—Shin Jin-wook, a sociologist who studies civil society and democracy; Lee Seung-yoon, a social welfare scholar and field researcher in the field of labor; Yang Seung-hoon, a sociologist who studies regional industrial structures with an interest in the youth labor market; and Lee Jae-jeong, a researcher of precarious labor and social welfare and active as a representative of several social movement organizations—we examine the main actors of the December 3rd Square in a three-dimensional manner, from those who created it to those who were erased from it.

"After the Square" provides a comprehensive overview of the political participation of citizens, including the far-right forces and cheering stick units that seemed to divide the square, and analyzes in greater detail how the far-right forces in Korea have historically changed (Shin Jin-wook) and what kind of democracy the youth in the square desire (Lee Jae-jung).

Afterwards, we examine the discourse of 'the extreme right-wing shift of men in their 20s and 30s' that emerged in contrast to the heated political participation of young women in their 20s and 30s (Yang Seung-hoon), and conclude by forecasting how this instability may affect political consciousness based on the results of an empirical study on the labor instability of the youth generation (Lee Seung-yoon).

This book's historical and timely analysis of political actors in civil society, including the Asphalt Far Right, the women of the Namtaeryeong rally, men in their 20s and 30s, and young unstable workers, is centered around the "square," firmly supporting the book's aim to view the December 3rd Square from a three-dimensional perspective.

The stories of the citizens who filled the Democracy Square, including youth, women, workers, and minorities, who were the main players in the square that was opened wide by martial law and impeachment, continue to be recorded.

In addition to this trend, "After the Square" critically examines the history of the citizens who create the dynamism of the square, or the citizens who do not show their faces in the square, and what they think and feel.

This is an effort to accurately understand the issues of democracy that are divided, combined, and formed according to political inclinations, ideologies, values, class, gender, generation, and ideology. It will serve as a welcome gift to readers seeking the driving force for the restoration and development of democracy after the 12?3 incident in 『After the Square』, leading them to a forum for discussion.

“The tragedy of which Marx speaks, that is, the social upheaval that brings with it immense human suffering, (…) at first passes like a short farce, but then returns as a true tragedy.

In the failed Munich beer hall coup of 1923, Adolf Hitler appeared to be nothing more than an anachronistic insurrectionist, but in 1933, as Führer, he abolished the Weimar Republic and established a Nazi dictatorship.

“If December 3rd is not to become a harbinger of such a tragedy, we must seriously reflect on December 3rd and transform ourselves and society.” (p. 9)

Far-right forces, cheering stick troops, men in their 20s and 30s, the unstable youth generation…

Restoring democracy is impossible without asking the public for a square.

Now that the "December 3rd Square" has closed and all eyes are on the early presidential election, what pressing issues in Korean society must be addressed? Before the heat of the square is swept away by the political wave, "After the Square" seeks to answer the following questions: △ How has the far-right evolved, and how destructive is it? △ What is the background of young women's political participation and solidarity? △ Have young men in their 20s and 30s actually become far-right? △ What impact does unstable youth employment have on their political awareness? △ What material conditions do young people inside and outside the square face? △ What kind of democracy do young people in the square ultimately desire?

· "The Crisis of Korean Democracy and Far-Right Fascism" _ Shin Jin-wook

: What are the seeds of Korea's far-right forces, and how are they evolving?

Sociologist Shin Jin-wook opens this book with the shocking declaration that the December 3 coup, which occurred amidst the global trend of democratic decline, was a decisive event that exposed the crisis of Korean democracy, and that the evolution of far-right forces that advocate anti-communism, anti-North Korea, anti-China, anti-feminism, and anti-homosexuality is a "sign of fascism."

The political consciousness of Korean citizens is attracting global attention.

In particular, the candlelight citizens who led the protests to impeach President Park Geun-hye in 2017 were recorded as the main players in the victory that prevented the regression of democracy.

However, the December 3 martial law that occurred seven years later forced us to reflect on the current state of Korean democracy and to realize that even a country like South Korea, which was considered to have achieved advanced democracy, could fall into dictatorship.

Moreover, the fact that this civil war was a coup d'état by a democratically elected president who destroyed his own legitimacy has decisively proven that "solid democracy" is close to an illusion.

When the Western District Court issued an arrest warrant for Yoon Seok-yeol, who was accused of being the leader of a rebellion, the coup forces, having lost their institutional power base, continuously called the far-right forces "the people" in an attempt to build a base of popular support.

This combination of extreme right-wing power and the masses led to the incident of rioting and breaking into the Western District Court, clearly revealing signs of fascism. According to the author, this can be said to be the fifth stage of Robert Paxton's six stages of fascism, where fascist tendencies enter the political system.

In other words, the violent incidents by far-right forces over the past four months and the conservative party's acquiescence and support were serious incidents that showed that fascism had developed to a considerable degree in Korean society.

Shin Jin-wook asserts that although the impeachment of Yoon Seok-yeol halted the development of fascism, the far-right's activities were not temporary or impulsive.

The far-right power elite organizations, mass communities, and some of those with far-right beliefs that have been built over a long period since democratization have only become visible in this impeachment situation.

As can be seen in the graph in Chapter 1 of this book (see page 45), over the past 20 years, the participation rate of those who are “very conservative” in Korean society has been similar to that of those who are “very progressive” since 2019, but has surpassed that of “very progressive” since the recent impeachment rally.

Therefore, we must not forget that even though the far-right movement appears to have temporarily stalled in the wake of the early presidential election held immediately following the impeachment of Yoon Seok-yeol, it can be politically reactivated at any time if the opportunity arises.

“If you thought that the cruel slogans like ‘punish,’ ‘kill,’ and ‘tread on’ that appeared at the protests opposing the impeachment of President Yoon Seok-yeol were merely a hysterical reaction of conservatives facing the threat of impeachment and a change of government, you would be mistaken.

(…) Many people have become accustomed to calling themselves ‘right-wing’ and, through their hostility toward the ‘left,’ dividing ‘us’ and ‘them,’ and objectifying ‘them’ as ‘enemies’ of the Republic of Korea, ‘non-citizens’ who must be expelled, and ‘inhumans’ who can be eliminated.” (p. 60)

In particular, the author points out that far-right forces can pose a significant threat to democracy as they become increasingly radical in their language and actions, centered around hatred for specific targets.

In this impeachment situation, we have experienced a situation where “state violence that destroys someone’s dignity can be committed with the consent and participation of other members of society.”

The author worries that if the combination of the conservative party and the asphalt right is dismissed as a mere "farce," we may be facing a much greater "tragedy" in the future.

At the same time, he emphasizes that rather than simply viewing the current reality as a dichotomy of whether it is fascism or not, we must look at the 'entire process by which fascism was born and grew.'

A precise understanding of the ever-changing and evolving far-right forces is essential to “responding to the vulnerabilities of Korean democracy and building a stronger defense wall for democracy and human rights.”

· "The Square Asks, the Youth Answers" _Lee Jae-jeong

: What was the core of democracy that the youth of the square drew that winter?

As a researcher and activist, Lee Jae-jeong took the plaza as a site in 2024 and recorded its voices and ultimate aspirations.

Based on an online survey conducted by the Youth for Yoon Seok-yeol's Resignation (hereafter, Youth for Yoon Seok-yeol's Resignation) for approximately 1,000 young people who took to the plaza for about two weeks in January 2025, the author "collected in a multi-layered manner the motivations for participation, memorable scenes, perception of the crisis of democracy, and imagination of future society of the young people who participated in this plaza rally," quantified it, and worked to elucidate its meaning.

The background of this survey is the regret that “our stories standing in the square are not being drawn by our own hands.”

The older generation's response of praising the 'MZ generation' for their dedication to protecting democracy as 'admirable' and 'admirable' reveals, on the one hand, an underlying perception that does not recognize young people as 'full citizens'. In response, the young people themselves sought to understand the demands of the young people standing in the democratic square and connect them to political participation activities.

This plaza was attended by many young people who had experience participating in the Park Geun-hye impeachment rally, the gender equality movement, the climate crisis response movement, and rallies related to social disasters. They were feeling angry at the Yoon Seok-yeol administration, which is clearly responsible for the Itaewon tragedy, the death of Chae Sang-byeong, and the KAIST student “silencing” incident, and they came to the plaza with a “desperate feeling that there is no place left to retreat.”

As the declaration continued on social media, young people “were always in the square,” and citizens who wanted to protect democracy learned from each other in the square and raised political awareness.

When asked what factors threaten democracy, young people cited 'concentration and abuse of power' and 'widening economic inequality' as the main threats.

Considering that in 2017, the square was primarily focused on political issues such as abuse of state power and prosecutorial reform, addressing economic inequality appears to be a new agenda.

A closer look at the content reveals that the youth point out that “differences in class, gender, education, region of origin, and upbringing within the younger generation are leading to social disparities.”

These responses from young people suggest that resolving economic polarization is an essential element of democracy, and that the political world must seriously embrace this demand.

He also responded that while 'investigating and punishing those responsible for crimes of sedition' is important as a way to restore democracy, 'solving social problems through social reform' is equally important.

Although this impeachment rally became a hot topic due to its cheerful protest grammar, including cheering sticks, K-pop, and flags, the youth came to the square not only with a desire to eliminate the structural absurdity that made this civil war possible, but also with a desire for fundamental reform that would eliminate inequality and discrimination.

Today's young people experience inequality and the collapse of the social ladder in all aspects of their lives, including education, housing, assets, and labor.

As public criticism of President Yoon Seok-yeol grew, the youth unemployment rate rose sharply, from 4.1% in August 2024 to 7.5% in March 2025.

(…) In order to guarantee the free political decision-making of the younger generation, it is necessary to resolve the economic gap problem so that they can achieve a substantial improvement in their abilities, and to create a channel where young people of various classes, genders, educational backgrounds, regions, and social statuses can participate in the political decision-making process and have their voices heard in a comprehensive manner.

(Pages 97-98)

Above all, this plaza was different from the previous ones in that it was a space of hospitality where people could learn from each other and share.

Lee Jae-jung emphasized solidarity, care, and community as the message the plaza of 2024 left for our society.

Citizens in the square became accustomed to the unfamiliar grammar of protest, and existing activist groups tried to maintain a culture of equality by looking after and being considerate of one another, such as by reading the declaration of “Everyone’s Promise for an Equal Assembly” and distributing food trucks and hot packs to welcome new faces to the square.

As the youth of the square most envision a future where equality and diversity are respected, Lee Jae-jung concludes this chapter by emphasizing the need to remember and continue the narrative of democracy based on care, solidarity, diversity, and difference in this square.

· "2030 Male Frame War" _ Yang Seung-hoon

: Are men in their 20s and 30s really the vanguard of the far right?

Sociologist Yang Seung-hoon examines the question, “Are men in their 20s and 30s truly politically conservative or far-right?” by connecting it to the public square.

In this impeachment situation, unlike the image of women in their 20s and 30s as progressives, the frame defining men in their 20s and 30s was, above all, ‘extreme right-wing’ or ‘conservative.’

The frame was primarily created based on the gender ratio of the rally participants, and was further strengthened as the faces of male participants were highlighted in events such as the Western District Court riot, the university campus rally, and the provocative actions of the 'New Men's Solidarity.'

The author argues that there is a need to examine society's perspective on men in their 20s and 30s, and attempts a 'fact check on men in their 20s and 30s.'

Yang Seung-hoon points out that the young male population is not homogeneous, that many of them have fluid political leanings and value orientations, and that even if they harbor anti-Chinese and anti-feminist sentiments, they are not extreme right-wingers who threaten to undermine the democratic system.

He then argues that if young men are relatively passive in the social participation arena symbolized by the plaza, the cause is not their conservatism or extreme rightward shift, but rather the contradictions and tensions that arise from the failure to find a “new role model” suited to the changing times in a situation where they have lost “the power as breadwinners enjoyed by their fathers’ generation.”

The '2030 Men' are clearly distinct from the mainstream right wing in Korea, which aims for a wealthy and powerful nation based on anti-communist, anti-North Korea, and anti-union policies.

Unlike the Korean right-wing, which actively opposed the impeachment of Yoon Seok-yeol, more than half of men in their 20s and 30s supported the impeachment.

Even among voters who chose Yoon Seok-yeol in the 2022 presidential election, a series of survey results suggest that they did not show extreme right-wing positions, such as supporting him during the impeachment process.

Although shocking incidents such as the Western District Court riot, the Northwest Youth League, and the New Men's Solidarity have been reported many times, the author argues that it is not true to label the 2030 male group as "extreme right-wing" because "there are only a handful of right-wing extremists causing disturbances among men in their 20s and 30s, and their support among men in their 20s and 30s is minimal," and that it will not help in finding a path for progressive politics in the long term.

According to Yang Seung-hoon, men in their 20s and 30s are ‘swing voters.’

The sentiments of the online community, which is their main activity space, such as “anti-Democratic Party, anti-feminism, pro-Yoon Seok-yeol, second-choice men, etc.”, cannot be a sign of extreme right-wing or conservative tendencies, and they say that “rather than choosing a political party for each election, they have voted based on their values and interests or their evaluation of the government and each political faction.”

Yang Seung-hoon argues that the role of progressive politics is to understand the still-flexible and unstable political orientation and party support tendencies of men in their 20s and 30s, and to persuade and bring them into the political arena.

In conclusion, we argue that “a full-fledged discussion on the creation of a new political space” is necessary, and we add discussions on gender equality in service, pension systems, and family rights as examples of such political space.

“Within Pemco, there is a strong sense of hostility towards the established political forces and the younger generation (especially the 86 generation).

According to sociologist Koo Jeong-woo, Femco is interested in issues where positions are polarized.

They prefer fighting the establishment rather than open hatred or attacks on minorities, and their main emotion is antipathy toward the existing order.

“In other words, although Pemco’s political stance is very unstable, if a political force emerges that can identify their grievances and political desires and deliver a clear message, there is a high possibility that they will quickly unite and take action.” (p. 149)

· "Melting Labor, Youth Finding Solidarity Difficult" _Lee Seung-yoon

: Is class-conscious political participation possible for young people in the era of liquid labor?

Lee Seung-yoon, a social policy researcher, empirically analyzes the material conditions of the lives of young people living outside the public square, and, using overseas examples, examines how their political consciousness can develop.

Lee Seung-yoon distances himself from the simple youth generation theory of “progressive young women, conservative young men” that has spread in the conflict between the pro- and anti-impeachment camps, and instead focuses on the sociological reality in which “various young people with different life trajectories and political consciousness coexist” within the categories of young men and young women.

Starting from Marx's proposition that "existence determines consciousness," Seungyoon Lee proposes a historical materialist approach that views young people not only from ideological and political perspectives such as progressive and conservative, or participants and non-participants in the impeachment rally, but also from a perspective centered on the material foundations of labor and class.

To this end, we derived an instability index by synthesizing three aspects: income, employment type, and social insurance coverage, and analyzed the long-term stratification patterns of the youth (19-34 years old) and non-youth (35-54 years old).

This analysis clearly shows that over the past 20 years, there has been a growing trend of instability, particularly among the younger generation, and a deepening polarization within the generation.

The instability of young people is closely related to the growing trend of “liquefied labor,” a phenomenon in which “the boundaries of labor as we have traditionally understood them are melting away, and the concept of labor as defined by existing legal systems is becoming ambiguous,” such as freelancers, call center workers, platform workers, and young people who alternate between unemployment and employment.

While irregular work in terms of time, form, and employment is on the rise, the current legal system relies on standard employment relationships, leaving workers with high levels of instability vulnerable to various social safety nets. One social group that is particularly acutely affected by this problem is the youth precariat.

The author attempts further analysis by adding a gender axis to this, and what is interesting is that while polarization tends to deepen among both young men and young women, the 'very insecure' group has increased noticeably among young men compared to young women.

In addition, to determine how labor instability affects social perception, we examined 'subjective class perception' and 'attitudes toward the possibility of social mobility'. We found that while both young men and women exhibited a pattern of being more pessimistic about the possibility of upward mobility when objective instability was high, young men exhibited a stronger level of pessimism when faced with the same level of instability.

The author cautiously points out that the analysis results, which show that one in two young men are in "very unstable" working conditions and that young men show more despair than hope in terms of their chances of upward mobility, can provide a clue to understanding various discourses and phenomena in Korean society surrounding men in their 20s and 30s.

The author emphasizes that, rather than hastily judging reality with generational theories, we must advance social solidarity against an unequal social system through active political and social movement practices, as this kind of existential instability can lead to political consciousness that goes in very conflicting directions, such as distrust of institutional politics in general, political resignation, demands for radical left-wing politics, or, conversely, support for far-right populism.

“Not all young people in precarious employment are politically progressive or supportive of systemic change.

Some studies indicate that their disillusionment with the system may lead them to show extreme right-wing tendencies or support populist parties.

“Both the leftist currents demanding expanded redistribution and social rights and the rightist currents expressing resistance to immigration and multicultural policies stem from a common perception of ‘distrust in institutional politics.’” (p. 208)

The crisis and possibility of democracy were both present in the square.

Transcending hate, polarization, and generationalism, we explore the diverse layers of citizenship.

May, when the shock of the night of civil war had not yet subsided.

Among the candidates who have declared their candidacy for the presidential election, some call themselves “candidates of the square,” some are unable to decide on a political stance on the insurrectionists, as if they have forgotten the reason for holding an early presidential election in the first place, and some are boldly revealing anti-China and anti-feminist sentiments by bringing up the 2021 pledge to “abolish the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family.”

Amidst a war of words fueled by half-baked promises, negativity, and hate, we are struggling through a time when political engineering takes precedence over democratic values, as if the unprecedented national emergency had never passed.

Hatred, polarization, and generationalism are just other names for the dangerous standards that divide a society into four.

"After the Square" is the result of focusing on the "citizens of the square" as a starting point for examining the crisis of democracy revealed by the coup d'état and seeking a better future for democracy.

In doing so, the four authors sought to intervene in the discourse that dichotomizes people by gender, generation, faction, and ideology, or generalizes a group as possessing homogeneous and single attributes, and considered ways to realize and sustain the value of diversity that blossomed in the square beyond the square.

'Plaza,' 'society,' and 'politics' are not separate entities, and democracy can function healthily only when we continuously imagine and invent new plazas, new societies, and new politics together with diverse citizens.

I hope this book can create a small crack in the wall that divides citizens and politics, inside and outside the square.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: May 26, 2025

- Page count, weight, size: 232 pages | 414g | 145*223*20mm

- ISBN13: 9791141610333

- ISBN10: 1141610337

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)