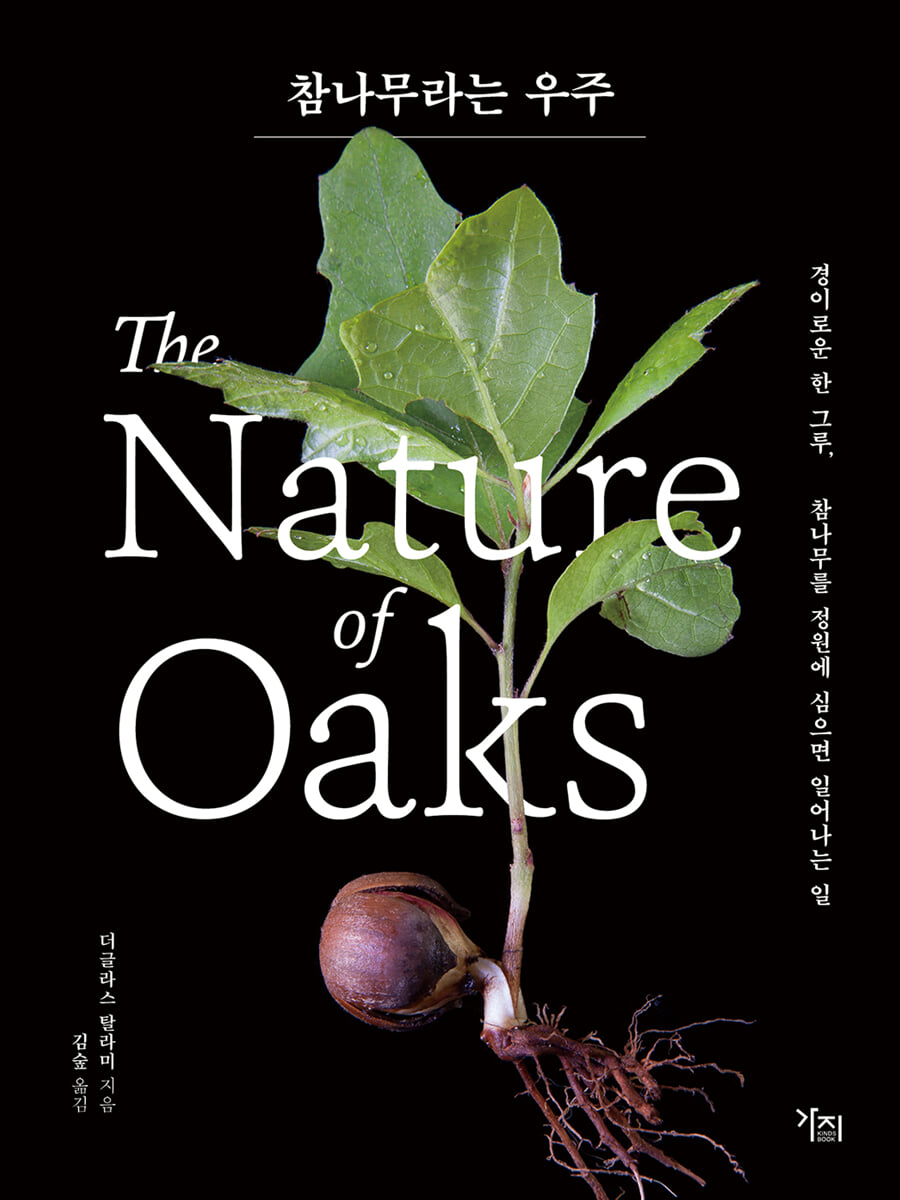

The universe called oak

|

Description

Book Introduction

The Story of the Oak Tree, a Wonderful Tree

Talami, an entomologist who picked up an oak acorn on a walk 18 years ago, brought it home, planted it, and grew it into a large tree measuring 14 meters tall and 1.2 meters in circumference, becomes a witness to the struggles of various plants and animals for survival and reproduction that unfold around the oak tree.

And one year, I decided to carefully observe and record the ecosystem surrounding the oak tree and the benefits it brings to our lives every month.

This book is the valuable result.

From the birds and wildlife that visit oak trees with each passing season, to the vast numbers and varieties of insects that play a crucial role in sustaining the food chain, to the world of fungi and microorganisms that cling to the fallen leaves and gigantic roots, often unseen by the naked eye, Tallamy meticulously observes the ecological events that unfold within a single oak tree over the course of a year, unfolding a story of an ecosystem that is almost like a universe.

So to speak, this book is a natural ecology textbook that delves deep into the depths of an oak tree.

Talami, an entomologist who picked up an oak acorn on a walk 18 years ago, brought it home, planted it, and grew it into a large tree measuring 14 meters tall and 1.2 meters in circumference, becomes a witness to the struggles of various plants and animals for survival and reproduction that unfold around the oak tree.

And one year, I decided to carefully observe and record the ecosystem surrounding the oak tree and the benefits it brings to our lives every month.

This book is the valuable result.

From the birds and wildlife that visit oak trees with each passing season, to the vast numbers and varieties of insects that play a crucial role in sustaining the food chain, to the world of fungi and microorganisms that cling to the fallen leaves and gigantic roots, often unseen by the naked eye, Tallamy meticulously observes the ecological events that unfold within a single oak tree over the course of a year, unfolding a story of an ecosystem that is almost like a universe.

So to speak, this book is a natural ecology textbook that delves deep into the depths of an oak tree.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Recommendation

Translator's Preface

prolog

october

A long-standing symbiotic relationship with birds

Why Oak Trees Hide

November

Best Protein Supplements

The acorn-weevil-ant link

december

Deciduous trees that do not lose their leaves even in winter

january

What do birds eat in winter?

What do insects eat to survive?

Keystone plant

Why Oak is the Best

february

Some misunderstandings

March

organic matter of invaluable value

What Oak Leaves Do

Memories of the days when we burned fallen leaves

april

gall

How wasp larvae live

When oak pollen flies

habitat of endangered species

May

migratory bird migration

A garden where native plants grow

Why an oak tree teeming with bugs is welcome

special beauty

The cicada that became a destroyer

Leaf shape

June

Cicada generation cycle

Reproductive strategies of oak-horned cicadas

You have to be weird to survive

Fake head of a green butterfly

July

Oak and mistletoe

The beautiful and scary wedge moth

How to Eat the Tough Leaves of July

The insect that signals the end of summer

What the size and shape of an acorn tell us

August

ecosystem services

Break through the oak barrier

winged natural enemy

Shield bugs and predators

cicadas living on oak trees

cicada-eating bees

September

walking stick

What is leaf litter to a butterfly?

Impressive ability, long tail

Preparing for winter

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

Appendix 1_How to Plant an Oak Tree

Appendix 2: List of Creatures in the Book

References

Search

Translator's Preface

prolog

october

A long-standing symbiotic relationship with birds

Why Oak Trees Hide

November

Best Protein Supplements

The acorn-weevil-ant link

december

Deciduous trees that do not lose their leaves even in winter

january

What do birds eat in winter?

What do insects eat to survive?

Keystone plant

Why Oak is the Best

february

Some misunderstandings

March

organic matter of invaluable value

What Oak Leaves Do

Memories of the days when we burned fallen leaves

april

gall

How wasp larvae live

When oak pollen flies

habitat of endangered species

May

migratory bird migration

A garden where native plants grow

Why an oak tree teeming with bugs is welcome

special beauty

The cicada that became a destroyer

Leaf shape

June

Cicada generation cycle

Reproductive strategies of oak-horned cicadas

You have to be weird to survive

Fake head of a green butterfly

July

Oak and mistletoe

The beautiful and scary wedge moth

How to Eat the Tough Leaves of July

The insect that signals the end of summer

What the size and shape of an acorn tell us

August

ecosystem services

Break through the oak barrier

winged natural enemy

Shield bugs and predators

cicadas living on oak trees

cicada-eating bees

September

walking stick

What is leaf litter to a butterfly?

Impressive ability, long tail

Preparing for winter

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

Appendix 1_How to Plant an Oak Tree

Appendix 2: List of Creatures in the Book

References

Search

Detailed image

Into the book

If you don't have a single oak tree in your home, you're missing out on the many wonderful life events taking place around you on Earth.

You'll never know unless someone tells you.

Similar books could be written about pines, cherry trees, elms, and birches, and any other tree could tell a unique and fascinating story, but none would be as impressive as the oak.

--- p.28, from "Prologue"

A single squirrel hides an average of 4,500 acorns each fall, eating a quarter of them before spring arrives.

If a Cooper's Hawk hunts a jay in December, the jay will not be able to eat a single acorn it has hidden.

As a result, statistics show that the squirrels plant 3,360 oak trees annually during their 7 to 17-year lifespan.

Without a doubt, the sapling is the primary helper that helps the oak tree spread faster than any other tree on Earth.

--- p.34, from “October_A Long-standing Symbiotic Relationship with Birds”

There is no trash in nature.

Even the acorns that have been used by weevils and are almost empty of shells.

These acorn shells are the perfect habitat for a colony of ant colonies and are large enough to accommodate up to 100 ants.

It is not easy for an ant, whose body is only half the size of a grain of rice, to bore a hole in an acorn, but the acorn where the acorn weevil larva lives already has a hole in it.

--- p.49, from “November_The Link Between Acorns, Weevils, and Ants”

Among deciduous trees growing in temperate climates with distinct four seasons, the phenomenon of not losing leaves even in winter is quite unique.

And such unique characteristics in nature pose a challenge to ecologists.

Most trees shed their leaves before winter, but why do some trees not?

--- p.55, from “December_Deciduous trees that don’t lose their leaves even in winter”

If we view insects not simply as "six-legged bugs," but as valuable food sources for birds, amphibians, reptiles, and mammals, we will be able to properly understand the ecological significance and crisis of insect decline, and even understand why we must prevent it.

--- p.69, from “January_What do birds eat in winter?”

Most insects can penetrate the chemical defenses of one or two plant species that have a common defense system.

To put it another way, most insects can only eat a few plants and are unable to eat anything else! Biologists call this "host plant specialization," and nearly 90 percent of herbivorous insects live in this way, foraging for a specific plant.

--- p.72, from “January_What Do Insects Eat to Live?”

It's not clear, but there's a lot more life below the surface than above it.

Countless creatures depend on oak trees at some point in their lives, including mammals and birds, hundreds of species of moths, butterflies, caterpillars, beetles, long-tailed beetles, shield beetles, cicadas, leafhoppers, horned cicadas, wasps, and hundreds of other smaller creatures that are even more diverse.

--- p.99, from “March_Priceless Organic Matter”

Oak leaves decompose very slowly, providing shelter, food, and a moist environment for decomposers for up to three years.

Because the gaps left by decomposing fallen leaves are filled each year by new leaves that fall, the ground beneath oak trees is always overflowing with leaves going through various stages of decomposition.

In contrast, most deciduous trees do not.

--- p.104, from “March_What Oak Leaves Do”

Physically, the galls are the result of the galls' ability to alter the normal growth patterns of oak tissue.

They provide homes and shelters for larvae, food for wasps, and sometimes just remain as galls on oak trees.

The researchers speculate that this is the big picture drawn by the wasp.

But if this was truly what the wasps wanted, shouldn't the oak trees have also evolved to mitigate the attacks of so many wasps and to benefit themselves ecologically?

--- p.123, from “April_How Wasp Larvae Live”

“There’s a magnolia tree on the oak tree in the front yard.” At this, I immediately grabbed my camera because I realized that my wife wasn’t hearing the call of a tree from China, but of a magnolia warbler, the prettiest of the migratory birds that visit our yard at this time of year.

The magpie isn't the only bird my wife brings me news of in May, when the majority of migratory birds visit.

--- p.133, from “May_Migration of Migratory Birds”

Any birder worth his salt must know exactly which trees migratory birds visit in the spring.

That's an oak tree! How could millions of birders make a wrong choice? I don't think so.

A few years ago, one of our lab students, Christie Bell, did some research on this.

Christie compared the amount of time migrating spring pine grouse spent foraging in fifteen tree species in New Jersey.

The pine trees were three times longer than the oak trees, and six times longer than the birch trees, which came in third.

--- p.141, from “May_Garden where native plants grow”

After six weeks, the tiny larvae hatch, drop to the ground, and burrow into the soil until they find tree roots.

Once the larva finds a tree root, it sticks its stinger into it and sucks the wood until it is fully grown.

Given the right environment, a fully grown oak tree can sustain 20,000 to 30,000 cicada larvae attached to its roots without any noticeable atrophy.

--- p.166, from “June_Cicada Generation Cycle”

Late July is a time of explosive growth of modified endosperms, once part of oak blossoms, and anyone can easily spot small, unripe acorns ripening on the branches.

In acorns, the 'cap' (also called the apex) develops first, and over time the lower part ripens.

The final size will be determined by how much energy is supplied to each acorn.

The size and shape of acorns are also among the most diverse features of the Quercus genus.

--- p.208, from “July_What the Size and Shape of Acorns Tell Us”

When heavy rain falls on the surface without anything to block it from the upper layers, the intense pressure can cause soil compaction.

If there were something in nature that could dissipate the energy of raindrops before they hit the ground, or absorb the volume of water that a huge storm would pour down, that would be a valuable ecosystem service in itself.

(The function of the ecosystem that benefits our lives in many ways).

And oak trees perform both roles very well.

--- p.215, from “August_Ecosystem Services”

Decades after a tree dies, the carbon is released back into the atmosphere.

Therefore, planting a lot of fast-growing but short-lived trees like maples and pines for carbon sequestration is simply passing the burden on to the next generation.

Rather, it is more ideal to plant tree species that store as much carbon as possible within their bodies and release it steadily over hundreds of years. A prime example of this is the oak tree, which is large, long-lived, and grows densely anywhere.

--- p.218, from “August_Ecosystem Services”

One day, while I was counting the number of caterpillars living in the oak tree in my yard, I came across a striped leafroller that was dodging my attacks with great skill.

This moth constructs a funnel-shaped shelter with three leaves, hides inside, and rarely comes out. It also lines the gaps between the leaves so tightly that all entrances are blocked to prevent predators or parasites from entering.

Although, while I was observing the sight with wonder, a spotted wasp appeared from somewhere and stuck its rear end between the dense threads made by the larva.

--- p.226, from “August_Winged Predator”

When the caterpillars of the Phalaenopsis butterfly have completed their growth stage, they fall to the ground and burrow into the layer of fallen leaves near the trunk of an oak tree to metamorphose.

This last step is crucial for moths and butterflies that use oak leaves for growth and reproduction.

In fact, there are only a few species that spend their entire life cycle on oak trees.

Of the hundreds of species of caterpillars that use oak as their host plant, more than 90 percent of them drop off the oak tree on their own after they are fully grown and pupate in the ground or in the leaf litter beneath the tree.

--- p.256, from “August_What is the fallen leaves to the butterfly?”

Birds consider feeders as one of several temporary seed-producing locations during this season.

So, before someone else can get them, they try to hide as many seeds as possible in a safe place where they can eat them all by themselves.

And this is when your oak tree becomes useful again.

Among the various oak trees, the oak has rough bark, making it ideal for hiding seeds in the nooks and crannies of the bark.

There are probably thousands of places on a single tree where seeds can be hidden.

If it's an old oak tree, there are many grooves left by broken branches or holes made by woodpeckers for nesting.

All are good places to hide seeds.

You'll never know unless someone tells you.

Similar books could be written about pines, cherry trees, elms, and birches, and any other tree could tell a unique and fascinating story, but none would be as impressive as the oak.

--- p.28, from "Prologue"

A single squirrel hides an average of 4,500 acorns each fall, eating a quarter of them before spring arrives.

If a Cooper's Hawk hunts a jay in December, the jay will not be able to eat a single acorn it has hidden.

As a result, statistics show that the squirrels plant 3,360 oak trees annually during their 7 to 17-year lifespan.

Without a doubt, the sapling is the primary helper that helps the oak tree spread faster than any other tree on Earth.

--- p.34, from “October_A Long-standing Symbiotic Relationship with Birds”

There is no trash in nature.

Even the acorns that have been used by weevils and are almost empty of shells.

These acorn shells are the perfect habitat for a colony of ant colonies and are large enough to accommodate up to 100 ants.

It is not easy for an ant, whose body is only half the size of a grain of rice, to bore a hole in an acorn, but the acorn where the acorn weevil larva lives already has a hole in it.

--- p.49, from “November_The Link Between Acorns, Weevils, and Ants”

Among deciduous trees growing in temperate climates with distinct four seasons, the phenomenon of not losing leaves even in winter is quite unique.

And such unique characteristics in nature pose a challenge to ecologists.

Most trees shed their leaves before winter, but why do some trees not?

--- p.55, from “December_Deciduous trees that don’t lose their leaves even in winter”

If we view insects not simply as "six-legged bugs," but as valuable food sources for birds, amphibians, reptiles, and mammals, we will be able to properly understand the ecological significance and crisis of insect decline, and even understand why we must prevent it.

--- p.69, from “January_What do birds eat in winter?”

Most insects can penetrate the chemical defenses of one or two plant species that have a common defense system.

To put it another way, most insects can only eat a few plants and are unable to eat anything else! Biologists call this "host plant specialization," and nearly 90 percent of herbivorous insects live in this way, foraging for a specific plant.

--- p.72, from “January_What Do Insects Eat to Live?”

It's not clear, but there's a lot more life below the surface than above it.

Countless creatures depend on oak trees at some point in their lives, including mammals and birds, hundreds of species of moths, butterflies, caterpillars, beetles, long-tailed beetles, shield beetles, cicadas, leafhoppers, horned cicadas, wasps, and hundreds of other smaller creatures that are even more diverse.

--- p.99, from “March_Priceless Organic Matter”

Oak leaves decompose very slowly, providing shelter, food, and a moist environment for decomposers for up to three years.

Because the gaps left by decomposing fallen leaves are filled each year by new leaves that fall, the ground beneath oak trees is always overflowing with leaves going through various stages of decomposition.

In contrast, most deciduous trees do not.

--- p.104, from “March_What Oak Leaves Do”

Physically, the galls are the result of the galls' ability to alter the normal growth patterns of oak tissue.

They provide homes and shelters for larvae, food for wasps, and sometimes just remain as galls on oak trees.

The researchers speculate that this is the big picture drawn by the wasp.

But if this was truly what the wasps wanted, shouldn't the oak trees have also evolved to mitigate the attacks of so many wasps and to benefit themselves ecologically?

--- p.123, from “April_How Wasp Larvae Live”

“There’s a magnolia tree on the oak tree in the front yard.” At this, I immediately grabbed my camera because I realized that my wife wasn’t hearing the call of a tree from China, but of a magnolia warbler, the prettiest of the migratory birds that visit our yard at this time of year.

The magpie isn't the only bird my wife brings me news of in May, when the majority of migratory birds visit.

--- p.133, from “May_Migration of Migratory Birds”

Any birder worth his salt must know exactly which trees migratory birds visit in the spring.

That's an oak tree! How could millions of birders make a wrong choice? I don't think so.

A few years ago, one of our lab students, Christie Bell, did some research on this.

Christie compared the amount of time migrating spring pine grouse spent foraging in fifteen tree species in New Jersey.

The pine trees were three times longer than the oak trees, and six times longer than the birch trees, which came in third.

--- p.141, from “May_Garden where native plants grow”

After six weeks, the tiny larvae hatch, drop to the ground, and burrow into the soil until they find tree roots.

Once the larva finds a tree root, it sticks its stinger into it and sucks the wood until it is fully grown.

Given the right environment, a fully grown oak tree can sustain 20,000 to 30,000 cicada larvae attached to its roots without any noticeable atrophy.

--- p.166, from “June_Cicada Generation Cycle”

Late July is a time of explosive growth of modified endosperms, once part of oak blossoms, and anyone can easily spot small, unripe acorns ripening on the branches.

In acorns, the 'cap' (also called the apex) develops first, and over time the lower part ripens.

The final size will be determined by how much energy is supplied to each acorn.

The size and shape of acorns are also among the most diverse features of the Quercus genus.

--- p.208, from “July_What the Size and Shape of Acorns Tell Us”

When heavy rain falls on the surface without anything to block it from the upper layers, the intense pressure can cause soil compaction.

If there were something in nature that could dissipate the energy of raindrops before they hit the ground, or absorb the volume of water that a huge storm would pour down, that would be a valuable ecosystem service in itself.

(The function of the ecosystem that benefits our lives in many ways).

And oak trees perform both roles very well.

--- p.215, from “August_Ecosystem Services”

Decades after a tree dies, the carbon is released back into the atmosphere.

Therefore, planting a lot of fast-growing but short-lived trees like maples and pines for carbon sequestration is simply passing the burden on to the next generation.

Rather, it is more ideal to plant tree species that store as much carbon as possible within their bodies and release it steadily over hundreds of years. A prime example of this is the oak tree, which is large, long-lived, and grows densely anywhere.

--- p.218, from “August_Ecosystem Services”

One day, while I was counting the number of caterpillars living in the oak tree in my yard, I came across a striped leafroller that was dodging my attacks with great skill.

This moth constructs a funnel-shaped shelter with three leaves, hides inside, and rarely comes out. It also lines the gaps between the leaves so tightly that all entrances are blocked to prevent predators or parasites from entering.

Although, while I was observing the sight with wonder, a spotted wasp appeared from somewhere and stuck its rear end between the dense threads made by the larva.

--- p.226, from “August_Winged Predator”

When the caterpillars of the Phalaenopsis butterfly have completed their growth stage, they fall to the ground and burrow into the layer of fallen leaves near the trunk of an oak tree to metamorphose.

This last step is crucial for moths and butterflies that use oak leaves for growth and reproduction.

In fact, there are only a few species that spend their entire life cycle on oak trees.

Of the hundreds of species of caterpillars that use oak as their host plant, more than 90 percent of them drop off the oak tree on their own after they are fully grown and pupate in the ground or in the leaf litter beneath the tree.

--- p.256, from “August_What is the fallen leaves to the butterfly?”

Birds consider feeders as one of several temporary seed-producing locations during this season.

So, before someone else can get them, they try to hide as many seeds as possible in a safe place where they can eat them all by themselves.

And this is when your oak tree becomes useful again.

Among the various oak trees, the oak has rough bark, making it ideal for hiding seeds in the nooks and crannies of the bark.

There are probably thousands of places on a single tree where seeds can be hidden.

If it's an old oak tree, there are many grooves left by broken branches or holes made by woodpeckers for nesting.

All are good places to hide seeds.

--- p.264, from “September_Preparing for Winter”

Publisher's Review

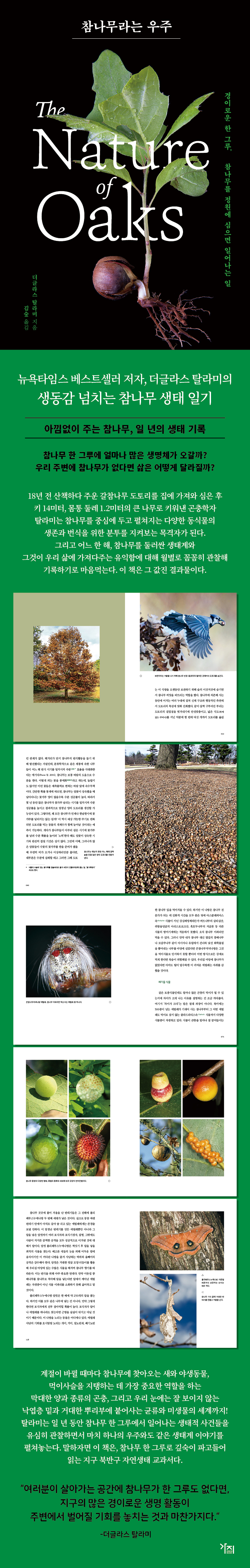

New York Times bestselling author, Douglas Tallamy

A vibrant oak ecology diary

The Generous Oak Tree: A Year's Ecological Record

:: How many living things can pass through a single oak tree?

:: How would life be different if there were no oak trees around us?

Douglas Tallamy, a New York Times bestselling author and renowned entomologist, takes a fascinating look at the oak, a keystone species in the ecosystems of the Northern Hemisphere, including North America and Korea.

He planted acorns from a Japanese oak tree he had picked up around his new home in a pot, let them sprout, and transplanted them to the yard. He has been growing them for 18 years, observing the various activities and changes in the ecosystem surrounding the oak tree.

As the author's story, which begins with a single oak tree, gradually expands into an understanding of the entire ecosystem that supports our lives, readers come to realize how closely interconnected all members of the ecosystem, including humans, are.

The author explores the story of an ecosystem, a universe in itself, by examining what birds and wild animals visit a single oak tree each season, and what insects and microorganisms live and interact with each other on its bark, leaves, flowers, fruits, roots, and even fallen leaves.

And when this ecosystem is maintained in a healthy state, it provides a comprehensive and easy-to-understand explanation of the valuable ecosystem services provided by a single oak tree, functions that benefit our lives in many ways.

Oak, a keystone species in the northern hemisphere ecosystem

Oak trees, which belong to the genus Quercus in the Fagaceae family in plant taxonomy, diverged from a common ancestor in present-day Southeast Asia about 60 million years ago.

It appeared on the North American continent 30 million years ago.

Currently, about 600 species are widely distributed across the temperate to tropical regions of the Northern Hemisphere of the Earth, and they provide enormous ecosystem services to surrounding creatures, including humans, during their average lifespan of 900 years.

Of all the trees found in the northern latitudes of the Earth, no other tree supports and sustains as many living things as the oak.

From birds that collect acorns, to insects that nest in oak trees, lay eggs, and feed, to their natural enemies, to the countless microorganisms that live in the thick layer of fallen leaves and on the roots underground, there are countless names of life forms that would not exist on Earth without oak trees.

Oak trees are, above all, an ideal habitat for breeding numerous insects.

Most insects, which are directly or indirectly connected to plants at the very bottom of the food chain, survive by eating only three or fewer specialized plants, and the oak tree serves as the most common host plant.

Without the vast numbers and abundance of insects that oak trees support, most of the birds we know would struggle to breed successfully.

Because of this role in firmly supporting the ecosystem, it is called a 'keystone plant' in the sense that if one of them is missing, the whole thing will collapse.

There are other trees that serve as keystones in nature, such as cherry trees, willow trees, pines, and maples, but the oak tree is by far the one that supports the most life.

Creatures that would disappear without oak trees

The author has been observing the activities of the living organisms that the oak tree attracts throughout the four seasons for 18 years, and has discovered the ecology of each and the connections that connect them to each other.

From October, when I started writing, to September of the following year, the book features a variety of creatures.

They are all born and grow on oak trees, live as parasites on oak trees, or obtain essential food for survival from oak trees.

The jay, which has evolved alongside oak trees for a long time and has become a master of 'carrying acorns'; the Korean warblers, which are good at finding and eating insects and spiders hiding in oak trees even in winter; the wasps that build gall-like egg cases (galls) on oak trees to raise their larvae and the wasps that lay eggs on the bodies of the larvae; the endangered silkworm moth that follows the scent of oak trees every night with its huge comb-shaped antennae and the bats and owls that prey on them; the cicadas that live as larvae attached to oak roots for as short as 4 years and as long as 17 years and the cicada-eating wasps that eat the cicadas that have come out into the world; the tunnel flies that dig tunnels in oak leaves and the stick insects and inchworms (larvae of the oak moth) that are very good at imitating branches; the shield insects that swarm in midsummer and the lacewings that come to eat them; the grasshoppers that announce the end of summer with their loud songs; the mistletoe, an epiphyte parasitized by oak trees; and mushrooms. And so on… … .

In addition, the author's vivid descriptions of the insects that live in bizarre forms hidden in the leaves, trunks, and fallen leaves of oak trees, the natural enemies that hunt them, and even the world of decomposers that dispose of dead animals and plant remains underground, invisible to our eyes, allow us to glimpse the breathtaking world of life that unfolds in a single oak tree throughout the four seasons.

Oak Growth History and Ecological Mysteries

The author also dramatically depicts the changes that occur in the life cycle of an acorn, a fruit dropped by an oak tree in the fall, that begins to take root the very next day and that can last for nearly a thousand years if the environment is right.

The roots spread three times wider than the exposed wood above the ground, the process by which leaf buds begin to sprout in early spring and grow into large, tough leaves full of lignin in August, the changes that occur when pollen flies in April, the time it takes for acorns to ripen completely, and the sight of dry leaves hanging on the branches even in winter, which is unusual for a deciduous tree in a temperate zone with four seasons… … .

These are all the characteristics that make oak most oak-like.

In addition, it explains in detail the interesting ecological phenomena observed during the growth process of oak trees, such as why a group of oak trees in a region sometimes produces an incredible amount of fruit at once, unlike in normal years, what information can be revealed through the size and shape of leaves and acorns, the phenomenon of the trunk becoming hollow as an oak tree ages, and the usefulness of rougher bark than that of other trees.

And these characteristics are the very basis for why oak trees support more living creatures than any other tree on Earth and help us live healthy lives.

The benefits oak trees bring to our lives

What the author looks into is not just the ecosystem itself.

It also tells us about the impact of the ecosystem surrounding oak trees on our lives, that is, the benefits provided by a single oak tree.

Oak trees, with their vast leaf surface and complex root system, act like sponges, dispersing the pressure of heavy rain and absorbing water, preventing major damage such as flooding, soil erosion, and destruction of aquatic ecosystems.

In fact, most of the rain that hits the oak's lush foliage (up to 11,000 liters annually) evaporates before it even reaches the ground, and heavy rainfall of just 5 centimeters, which would cause flooding on bare ground, is mostly captured by the oak's fallen leaves and the humus they produce as they decompose.

Moreover, in the age of climate crisis, carbon sequestration is considered the most important ecosystem service we receive from oak trees every day.

Like other plants, oaks absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere through photosynthesis and fix the carbon in their tissues, particularly through the rhizobacteria in their massive roots, which deposit carbon-rich glomalin into the surrounding soil throughout the tree's life cycle.

This carbon can remain in the soil for hundreds or even thousands of years without affecting atmospheric temperature.

In addition, we are reminded that the oak trees standing around us without a care in the world block strong winds and rain when the weather is bad, provide shade in the summer, and warmth in the winter, and are also very helpful in terms of energy economy.

With all this evidence, the author urges everyone to plant ecologically beneficial oak trees in their yards first, emphasizing that the oak trees we plant and nurture in the future will do more to alleviate the planet's rapidly worsening climate problems than almost any other plant on Earth.

If you want to plant an oak tree in your garden

There are many people who wish to have a large tree in their garden.

However, many people do not plant oak trees near their homes due to the misconception that they will grow too large, the hassle of clearing fallen leaves, the fear that their large roots will damage nearby roads or facilities, or that they will cause great damage when a typhoon uproots the tree trunk, branches, or roots.

The author, who inspired many North American gardeners through his previous works, 『Bringing Nature Home』 and 『Nature's Best Hope』, by suggesting the importance and specific methodologies of utilizing native plants in landscaping around us, also corrects common misconceptions and presents the right answers regarding the practicality of 'oak planting'.

Here are some guidelines for growing oak trees more healthily and safely, such as planting acorns or small seedlings to grow into large trees rather than transplanting large trees if possible, planting two or three trees at a time at an appropriate distance, and creating natural flower beds with native plants around the oak trees. We also carefully introduce tips for planting acorns or seedlings and caring for them while they grow.

Whether you simply want to plant an oak tree in your front yard, are curious about the ecosystem surrounding it, or simply want to express your gratitude for the irreplaceable role oak trees play in the health of our surrounding environment, after reading this remarkable book, you will see the ubiquitous oak tree in a completely different way.

A vibrant oak ecology diary

The Generous Oak Tree: A Year's Ecological Record

:: How many living things can pass through a single oak tree?

:: How would life be different if there were no oak trees around us?

Douglas Tallamy, a New York Times bestselling author and renowned entomologist, takes a fascinating look at the oak, a keystone species in the ecosystems of the Northern Hemisphere, including North America and Korea.

He planted acorns from a Japanese oak tree he had picked up around his new home in a pot, let them sprout, and transplanted them to the yard. He has been growing them for 18 years, observing the various activities and changes in the ecosystem surrounding the oak tree.

As the author's story, which begins with a single oak tree, gradually expands into an understanding of the entire ecosystem that supports our lives, readers come to realize how closely interconnected all members of the ecosystem, including humans, are.

The author explores the story of an ecosystem, a universe in itself, by examining what birds and wild animals visit a single oak tree each season, and what insects and microorganisms live and interact with each other on its bark, leaves, flowers, fruits, roots, and even fallen leaves.

And when this ecosystem is maintained in a healthy state, it provides a comprehensive and easy-to-understand explanation of the valuable ecosystem services provided by a single oak tree, functions that benefit our lives in many ways.

Oak, a keystone species in the northern hemisphere ecosystem

Oak trees, which belong to the genus Quercus in the Fagaceae family in plant taxonomy, diverged from a common ancestor in present-day Southeast Asia about 60 million years ago.

It appeared on the North American continent 30 million years ago.

Currently, about 600 species are widely distributed across the temperate to tropical regions of the Northern Hemisphere of the Earth, and they provide enormous ecosystem services to surrounding creatures, including humans, during their average lifespan of 900 years.

Of all the trees found in the northern latitudes of the Earth, no other tree supports and sustains as many living things as the oak.

From birds that collect acorns, to insects that nest in oak trees, lay eggs, and feed, to their natural enemies, to the countless microorganisms that live in the thick layer of fallen leaves and on the roots underground, there are countless names of life forms that would not exist on Earth without oak trees.

Oak trees are, above all, an ideal habitat for breeding numerous insects.

Most insects, which are directly or indirectly connected to plants at the very bottom of the food chain, survive by eating only three or fewer specialized plants, and the oak tree serves as the most common host plant.

Without the vast numbers and abundance of insects that oak trees support, most of the birds we know would struggle to breed successfully.

Because of this role in firmly supporting the ecosystem, it is called a 'keystone plant' in the sense that if one of them is missing, the whole thing will collapse.

There are other trees that serve as keystones in nature, such as cherry trees, willow trees, pines, and maples, but the oak tree is by far the one that supports the most life.

Creatures that would disappear without oak trees

The author has been observing the activities of the living organisms that the oak tree attracts throughout the four seasons for 18 years, and has discovered the ecology of each and the connections that connect them to each other.

From October, when I started writing, to September of the following year, the book features a variety of creatures.

They are all born and grow on oak trees, live as parasites on oak trees, or obtain essential food for survival from oak trees.

The jay, which has evolved alongside oak trees for a long time and has become a master of 'carrying acorns'; the Korean warblers, which are good at finding and eating insects and spiders hiding in oak trees even in winter; the wasps that build gall-like egg cases (galls) on oak trees to raise their larvae and the wasps that lay eggs on the bodies of the larvae; the endangered silkworm moth that follows the scent of oak trees every night with its huge comb-shaped antennae and the bats and owls that prey on them; the cicadas that live as larvae attached to oak roots for as short as 4 years and as long as 17 years and the cicada-eating wasps that eat the cicadas that have come out into the world; the tunnel flies that dig tunnels in oak leaves and the stick insects and inchworms (larvae of the oak moth) that are very good at imitating branches; the shield insects that swarm in midsummer and the lacewings that come to eat them; the grasshoppers that announce the end of summer with their loud songs; the mistletoe, an epiphyte parasitized by oak trees; and mushrooms. And so on… … .

In addition, the author's vivid descriptions of the insects that live in bizarre forms hidden in the leaves, trunks, and fallen leaves of oak trees, the natural enemies that hunt them, and even the world of decomposers that dispose of dead animals and plant remains underground, invisible to our eyes, allow us to glimpse the breathtaking world of life that unfolds in a single oak tree throughout the four seasons.

Oak Growth History and Ecological Mysteries

The author also dramatically depicts the changes that occur in the life cycle of an acorn, a fruit dropped by an oak tree in the fall, that begins to take root the very next day and that can last for nearly a thousand years if the environment is right.

The roots spread three times wider than the exposed wood above the ground, the process by which leaf buds begin to sprout in early spring and grow into large, tough leaves full of lignin in August, the changes that occur when pollen flies in April, the time it takes for acorns to ripen completely, and the sight of dry leaves hanging on the branches even in winter, which is unusual for a deciduous tree in a temperate zone with four seasons… … .

These are all the characteristics that make oak most oak-like.

In addition, it explains in detail the interesting ecological phenomena observed during the growth process of oak trees, such as why a group of oak trees in a region sometimes produces an incredible amount of fruit at once, unlike in normal years, what information can be revealed through the size and shape of leaves and acorns, the phenomenon of the trunk becoming hollow as an oak tree ages, and the usefulness of rougher bark than that of other trees.

And these characteristics are the very basis for why oak trees support more living creatures than any other tree on Earth and help us live healthy lives.

The benefits oak trees bring to our lives

What the author looks into is not just the ecosystem itself.

It also tells us about the impact of the ecosystem surrounding oak trees on our lives, that is, the benefits provided by a single oak tree.

Oak trees, with their vast leaf surface and complex root system, act like sponges, dispersing the pressure of heavy rain and absorbing water, preventing major damage such as flooding, soil erosion, and destruction of aquatic ecosystems.

In fact, most of the rain that hits the oak's lush foliage (up to 11,000 liters annually) evaporates before it even reaches the ground, and heavy rainfall of just 5 centimeters, which would cause flooding on bare ground, is mostly captured by the oak's fallen leaves and the humus they produce as they decompose.

Moreover, in the age of climate crisis, carbon sequestration is considered the most important ecosystem service we receive from oak trees every day.

Like other plants, oaks absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere through photosynthesis and fix the carbon in their tissues, particularly through the rhizobacteria in their massive roots, which deposit carbon-rich glomalin into the surrounding soil throughout the tree's life cycle.

This carbon can remain in the soil for hundreds or even thousands of years without affecting atmospheric temperature.

In addition, we are reminded that the oak trees standing around us without a care in the world block strong winds and rain when the weather is bad, provide shade in the summer, and warmth in the winter, and are also very helpful in terms of energy economy.

With all this evidence, the author urges everyone to plant ecologically beneficial oak trees in their yards first, emphasizing that the oak trees we plant and nurture in the future will do more to alleviate the planet's rapidly worsening climate problems than almost any other plant on Earth.

If you want to plant an oak tree in your garden

There are many people who wish to have a large tree in their garden.

However, many people do not plant oak trees near their homes due to the misconception that they will grow too large, the hassle of clearing fallen leaves, the fear that their large roots will damage nearby roads or facilities, or that they will cause great damage when a typhoon uproots the tree trunk, branches, or roots.

The author, who inspired many North American gardeners through his previous works, 『Bringing Nature Home』 and 『Nature's Best Hope』, by suggesting the importance and specific methodologies of utilizing native plants in landscaping around us, also corrects common misconceptions and presents the right answers regarding the practicality of 'oak planting'.

Here are some guidelines for growing oak trees more healthily and safely, such as planting acorns or small seedlings to grow into large trees rather than transplanting large trees if possible, planting two or three trees at a time at an appropriate distance, and creating natural flower beds with native plants around the oak trees. We also carefully introduce tips for planting acorns or seedlings and caring for them while they grow.

Whether you simply want to plant an oak tree in your front yard, are curious about the ecosystem surrounding it, or simply want to express your gratitude for the irreplaceable role oak trees play in the health of our surrounding environment, after reading this remarkable book, you will see the ubiquitous oak tree in a completely different way.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: September 15, 2023

- Page count, weight, size: 304 pages | 588g | 150*200*22mm

- ISBN13: 9791186440988

- ISBN10: 1186440988

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)