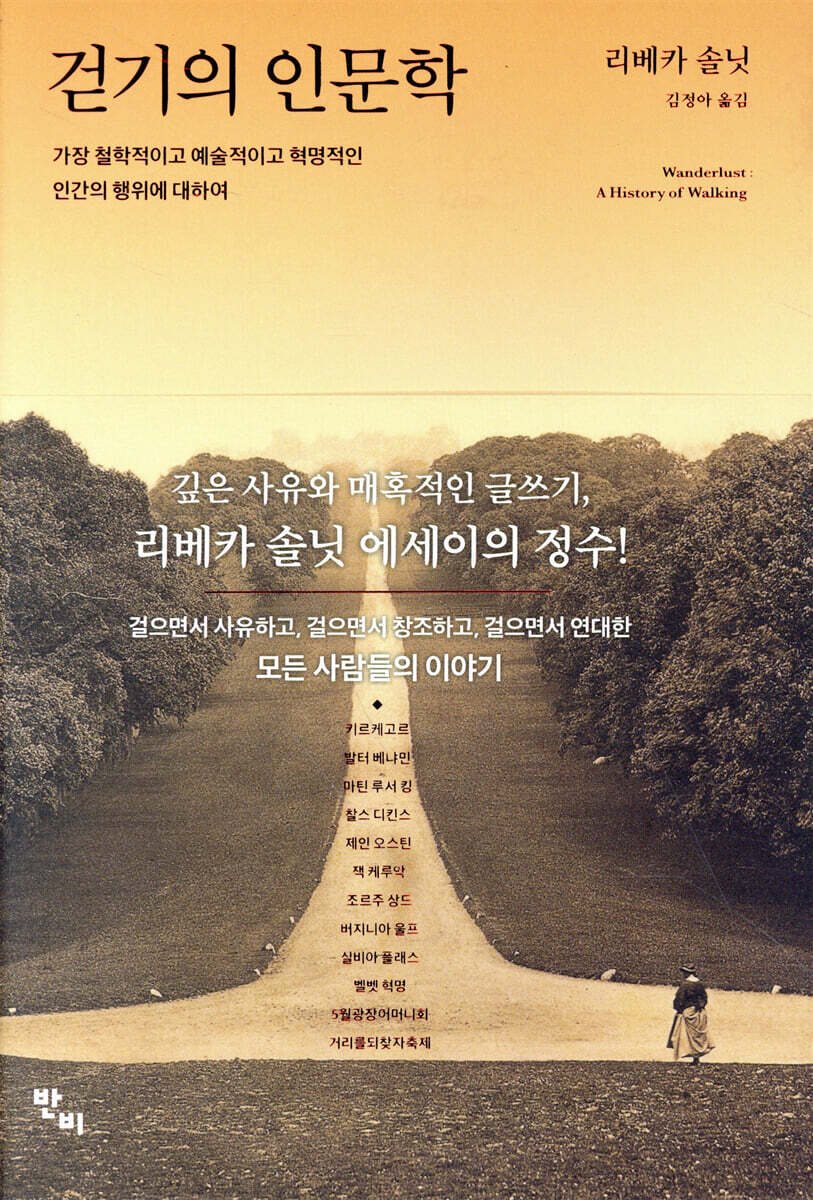

The Humanities of Walking

|

Description

Book Introduction

The essence of Rebecca Solnit's essays, written by 'Mansplaining' and selected by U-Tune Reader as one of '25 Thinkers Who Will Change Your World' in 2010, has received deep sympathy and wide support from Korean readers.

This book explores the philosophical, creative, and revolutionary possibilities of the most universal act of 'walking'.

Solnit seamlessly weaves together traditional methodologies of the humanities—history, philosophy, politics, literature, and art criticism—while also incorporating personal experiences, thereby completing her journey of exploration as a model for the humanities essay.

Part 1 explores the relationship between walking and thought, or between body and mind, through philosophers and writers who have chosen walking as a method of thought, and the relationship between walking and religion through walking as a pilgrimage.

Part 2 examines the process by which walking in nature became established as a cultural practice and taste throughout the 18th and 19th centuries through walking literature, travel literature, and walking groups.

Part 3 deals with walking in the 20th-century city, characterized by anonymity and diversity.

It points out that the possibility of entering public space is directly linked to the issue of leading a public life as a citizen, and analyzes the constraints based on gender, race, class, and sexual orientation, while exploring the political meaning of walking, such as marches, festivals, and revolutions.

Part 4 explores the crisis posed by today's changing pace of walking.

"The Humanities of Walking" comprehensively reconstructs numerous historical figures, canonical texts, ideas, and events from a new perspective.

Through this book, we can find entirely new answers to traditional philosophical motifs such as mind vs. body, private vs. public, city vs. country, individual vs. group, digested in Solnit's style, without excluding the perspectives and voices of minorities.

This book explores the philosophical, creative, and revolutionary possibilities of the most universal act of 'walking'.

Solnit seamlessly weaves together traditional methodologies of the humanities—history, philosophy, politics, literature, and art criticism—while also incorporating personal experiences, thereby completing her journey of exploration as a model for the humanities essay.

Part 1 explores the relationship between walking and thought, or between body and mind, through philosophers and writers who have chosen walking as a method of thought, and the relationship between walking and religion through walking as a pilgrimage.

Part 2 examines the process by which walking in nature became established as a cultural practice and taste throughout the 18th and 19th centuries through walking literature, travel literature, and walking groups.

Part 3 deals with walking in the 20th-century city, characterized by anonymity and diversity.

It points out that the possibility of entering public space is directly linked to the issue of leading a public life as a citizen, and analyzes the constraints based on gender, race, class, and sexual orientation, while exploring the political meaning of walking, such as marches, festivals, and revolutions.

Part 4 explores the crisis posed by today's changing pace of walking.

"The Humanities of Walking" comprehensively reconstructs numerous historical figures, canonical texts, ideas, and events from a new perspective.

Through this book, we can find entirely new answers to traditional philosophical motifs such as mind vs. body, private vs. public, city vs. country, individual vs. group, digested in Solnit's style, without excluding the perspectives and voices of minorities.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Recommendation

To Korean readers

Part 1: The Speed at which Thought Walks

1. Walking to the tip of the cape: Introduction

2 Steps of the Mind

3 The Beginning of Upright Walking: The Essence of Evolution

4 The Uphill Road to Grace: Pilgrimage

5 Mazes and Cadillacs: Walking into Symbols

Part 2: From the Garden to Nature

6. The way out of the garden

7 William Wordsworth's Two Legs

8 When Two Feet Fall into Sentiment: Walking Literature

9 History Goes to the Mountain: Mountaineering Literature

10 Meetings for Pedestrians, Struggles for Traffic

Part 3 On the Street

11 A City Where You Can Walk Alone

12 Flaneur, or Man Walking Through the City

13 Citizens of the Main Street: Festivals, Marches, Revolutions

14 City Nightlife: Women, Sex, and Public Spaces

Beyond the end of Part 4

15 Sisyphus goes to the gym, Psyche lives in a new town

16 Walking Art

17 Las Vegas, or the longest distance between two points

Acknowledgements

Translator's Note

main

Bibliographic information on walking quotes

To Korean readers

Part 1: The Speed at which Thought Walks

1. Walking to the tip of the cape: Introduction

2 Steps of the Mind

3 The Beginning of Upright Walking: The Essence of Evolution

4 The Uphill Road to Grace: Pilgrimage

5 Mazes and Cadillacs: Walking into Symbols

Part 2: From the Garden to Nature

6. The way out of the garden

7 William Wordsworth's Two Legs

8 When Two Feet Fall into Sentiment: Walking Literature

9 History Goes to the Mountain: Mountaineering Literature

10 Meetings for Pedestrians, Struggles for Traffic

Part 3 On the Street

11 A City Where You Can Walk Alone

12 Flaneur, or Man Walking Through the City

13 Citizens of the Main Street: Festivals, Marches, Revolutions

14 City Nightlife: Women, Sex, and Public Spaces

Beyond the end of Part 4

15 Sisyphus goes to the gym, Psyche lives in a new town

16 Walking Art

17 Las Vegas, or the longest distance between two points

Acknowledgements

Translator's Note

main

Bibliographic information on walking quotes

Publisher's Review

“I wanted to steal Solnit’s writing.

I am always overwhelmed by the writing, crafted with courageous language cultivated from the field, the insight of someone who has observed for a long time, a solid intellect built with sincerity, and a beautiful emotion that spreads between each line like a sunset.

After reading 『The Humanities of Walking』, I can guess a little bit about the secret.

I think the driving force behind this was walking, “recognizing the world through the body and recognizing the body through the world.”

This expanding text proves that the mere act of pushing one's body, the arduous act of walking, can transform someone into an environmental activist, a philosopher, a feminist, an artist, a meditator.

In proving it, Solnit becomes all of that being.” - Eunyu (author)

“Through this book, I realized that I have a wonderful weapon that no one can take away from me.

I think while walking, I dream of communicating with something other than myself while walking, I get new ideas while walking, and by walking, I am clearly different from before I started walking.

Rebecca Solnit testifies brilliantly in this book.

“The power of human beings to become a little different each time they walk, thinking more, longer, and more deeply.” - Jeong Yeo-ul (literary critic)

“Walking, as Rebecca Solnit says, means sending this world to a higher and farther place, that is, ‘progress.’

All over the world, people are walking to bridge the gap between race and gender.

“This is why we hear the history of hope in the voice of Rebecca Solnit, who tells the history of walking.” - Kim Yeon-su (novelist)

A letter of respect and solidarity from world-renowned intellectual Rebecca Solnit to Korean readers.

It was inspiring and awe-inspiring to see Koreans unite against an unjust regime last year.

But those on the other side of the world who knew our history were not surprised.

One of the themes of this book is that unarmed citizens walking out into public space are a tremendous force, sometimes a force for self-government, and sometimes a force to stop oppressive and rogue regimes.

[… … ] Democracy is often an experience.

It is the experience of physically coming together in a public space, the experience of seeing with our own eyes, the experience of not stepping back, the experience of walking until we reach our goal.

It is the greatest and most beautiful experience of power in the world where people live.

As the author, I am honored that this book is published in a country where the power of citizens to defend justice and freedom is being demonstrated in many ways, from the anti-globalization movement to recent events. - Rebecca Solnit, "To Korean Readers"

Rebecca Solnit, author of 'Mansplaining' and one of the '25 Thinkers Who Will Change Your World' by UtterLitter in 2010.

Solnit's writings also receive deep sympathy and support from Korean readers.

『Men Keep Trying to Teach Me』 and 『Far and Close』, published in Korea in 2015 and 2016 respectively, were named as books of the year by numerous media outlets.

In addition to 『Men Keep Trying to Educate Me』, which made Rebecca Solnit most famous, she is already known in Korea for books such as 『Gaze into These Ruins』 and 『Hope in the Darkness』, which highlighted her as an activist, and 『Far Away, Yet Close』, which highlighted her as an essayist. However, this book is more special as the starting point and comprehensive edition of Solnit's unique thoughts and methodology.

This is also why many writers and readers have been waiting for the publication of this book for a long time.

What makes this book even more special is the letter of respect, empathy, and solidarity that Rebecca Solnit sent to her Korean readers (and the author's unusually generous preface to the Korean edition).

Solnit, who was deeply impressed by the democratic achievements made by millions of citizens in the squares from the fall of 2016 to the spring of 2017, says she discovered another reason why "The Humanities of Walking" is still relevant nearly 20 years after its publication.

This is the 'power of unarmed citizens walking out into public space,' which is also the main theme of this book.

Through the preface to the Korean edition, which beautifully and clearly recreates the "experience of the greatest and most beautiful power," the author once again conveys a profound sense of emotion to the citizens of Korea.

Deep thought and captivating writing: the essence of Rebecca Solnit's essays.

A model for humanistic essays encompassing history, philosophy, politics, literature, and art criticism.

If we were to categorize Rebecca Solnit's books by another criterion, they would fall into two categories.

A book of short, poetic essays, written in one breath from beginning to end.

And among the latter, this book is the one that focuses most densely on a single topic.

Solnit seamlessly weaves together traditional methodologies from the humanities—history, philosophy, politics, literature, and art criticism—while also incorporating personal experience to create a richer journey. The author wrote this book not only through textual research and verification, but also through walking and experiencing it firsthand.

This book comprehensively covers almost every element and aspect of walking, including people walking and their gatherings, places where people walk, the forms and types of walking, literature and art that depict walking, the structure and evolution of the walking body, and the social conditions that allow for free walking. Ultimately, it speaks to the meaning and possibilities that the act of walking holds for humans, and is, in short, a model humanistic essay.

The numerous historical figures, canonical texts, ideas, and events covered in 『The Humanities of Walking』 are thoroughly digested by the author, and then interpreted and reconstructed with a comprehensive meaning.

Through this book, we explore the mind vs.

Physical, Private vs.

Public, City vs.

Rural, Private vs.

We can find a completely new answer to traditional philosophical motifs such as the group, digested in Solnit's style, without excluding the perspectives and voices of minorities.

The History of Walking and the Crisis of Walking

? The Meaning of Walking: Solnit presents compelling arguments for why walking should be a subject of humanistic inquiry.

Walking is an activity that is far removed from a production-oriented culture, and is an activity that is both a means and an end in itself.

This is a characteristic that applies equally to the humanities.

According to Solnit, the best way to reflect on your mind is to walk.

This entire book can be said to be a process of proving that “the history of walking embodies the history of thought.”

“Discovering a completely new perspective is a great happiness, and I can experience this happiness at any time even now.” (p. 19)

In a production-oriented culture, thinking is often seen as doing nothing, but doing nothing is not easy.

The best way to do nothing is to pretend to do something, and the closest thing to doing nothing is to walk.

Among the intentional actions of humans, walking is the one closest to the involuntary rhythm of the body (breathing, heartbeat).

Walking is a delicate balance between working and not working, between just being and doing something.

Could it be said that it is physical labor that produces nothing but thoughts, experiences, and arrivals? (p. 20)

Walking is both a means and an end, a journey and a destination. (p. 22)

The reason I like walking is because it's slow.

I think the mind has a similar speed to the two feet (less than 5 kilometers per hour).

If that idea is correct, then the pace at which modern life moves is faster than the pace at which thoughts move (p. 28).

To identify a place is to plant invisible seeds of memory and association in that place.

When you return to that place, the fruit of that seed awaits you.

New places mean new ideas, new possibilities.

Exploring the world is the best way to explore your mind.

Just as you must walk to see the world, you must walk to see your heart. (p. 32)

Walking and Philosophers: While Greek philosophers are often invoked to explain the close relationship between walking and thinking, Solnit points out that this was also the setting for Rousseau and his contemporaries.

It is true that the Greeks walked a lot, and that the names of the Stoics and the Peripatetics are related to walking, but it was Rousseau who first linked philosophical thinking to walking.

Solnit emphasizes that the unique and powerful thinking of Rousseau and Kierkegaard, and their characteristics as "hybrid philosophers and philosophical writers," is due to the works they wrote while walking.

The history of walking is longer than the history of humans.

However, if we consider walking as a kind of conscious cultural act rather than simply a means, the history of walking can be said to have begun in Europe only a few centuries ago.

And Rousseau is at its origin.

Its history was created by the feet of various people in the 18th century, but among them, the more scholarly ones sought to create a great tradition of walking by tracing the origins of walking to ancient Greece.

It was a time when Greek customs were both joyfully worshipped and distorted. (p. 33)

If Rousseau's writings are the precursor to the literature dealing with philosophical gait, it is because he was one of the first writers to consider it worthwhile to record in detail the circumstances in which his reflections took place.

If Rousseau was a radical, his most radical act was to reassess the value of personal, private experience (based on walking, solitude, and nature). (p. 45)

“I think the only time I could think that much, exist that much, experience that much, and become that much myself was when I was traveling alone on foot.

Walking on two feet energizes and refreshes my mind.

Should we say that if we stay in one place, our head won't work properly? Should we say that if our body moves, our mind will move too?

The countryside, the pleasant prospects that continue, the fresh air, the good appetite, the health that walking improves, the casual atmosphere of the tavern, the absence of anything that reminds me of my subjugation and my miserable situation.

All this frees my soul from its bonds, gives me more courage to think, and allows me to immerse myself in the vast ocean of beings.

“Thanks to this, I can freely combine, select, and utilize those beings without any discomfort or fear.” (p. 41)

Unlike the rigid format of a thesis, or the chronological format of a biography or history, the travelogue encourages digression and association.

Nearly a century and a half after Rousseau's death, James Joyce and Virginia Woolf, seeking to portray the workings of the mind, developed a style called stream of consciousness.

In Joyce's novel Ulysses and Woolf's novel Mrs. Dalloway, the jumbled thoughts and memories in the protagonists' heads are best resolved when they are walking down the street.

In other words, the type of thinking that best suits the non-analytical, spontaneous act of walking is this non-systematic, associative type of thinking.

Rousseau's "Reveries of a Solitary Walker" is one of the first paintings to illustrate this relationship between thought and walking. (p. 44)

? Evolutionary Perspectives, The Science of Walking: Through paleoanthropological discussions surrounding walking, this book examines the evolutionary impact of upright walking on the human body and society, and refutes the white-centric, patriarchal ideology that permeates evolutionary history.

British experts who had cheered Piltdown Man doubted that the child, named Taung Child, was an ancestor of mankind.

Scientists of that era were reluctant to accept the idea that their ancestors were African, and they were reluctant to accept evidence that they once walked on two legs while having small brains—evidence that our intelligence had come later, not earlier, in our evolution. (p. 65)

In current discussions, upright walking is the Rubicon that our evolving species crossed to become completely distinct from other primates.

We've achieved many wonderful results with upright walking.

Arches resembling Gothic architecture appeared on the body, and the entire body became longer up and down.

Starting from the bottom, the toes point in one direction, creating an arch on the inside of the foot.

As both legs are stretched out, the gluteus maximus is developed convexly.

The stomach became flat, the waist became flexible, the spine became straight, the shoulders lowered, the neck became longer, and the head was held upright.

When you look at a body standing upright, each part is exquisitely balanced, like a pillar. (Page 66)

There is a widespread belief in the human evolution literature that women are clumsier walkers.

The belief that women have brought a fatal curse upon the entire human species, that women have been merely helpers to men in the evolutionary process, and that walking is related to thinking, so women are bound to lack thinking, seem to be yet another relic left behind by Genesis.

If humans gained the freedom to go places they had never been before, to do things they had never done before, and to think freely when they learned to walk, women's freedom was often linked to sexuality, or more precisely, to a sexuality that required control and containment.

But such discussions are no longer about physiology but about ethics. (p. 78)

Scientists who talk about walking and evolution have one important point to make, no matter how far-fetched their claims may be.

It attempts to discuss the essential meaning of walking—in other words, it asks not what we make of walking, but what walking has made of us. (p. 79)

? Pilgrimage: This book explores the significance of pilgrimage as a "self-inflicted walk" in human history, encompassing experiences of pilgrimage to the Chimayo Shrine, the writings and lives of anti-war activists known as "Peace Pilgrims," and the Birmingham March, where Martin Luther King Jr. transformed traditional pilgrimage into a civil rights movement action.

If embarking on a pilgrimage is an expression of the soul's faith and hope through bodily movements, isn't pilgrimage an act of reconciling spirit and matter?

The idea that pilgrimage is a union of faith and action, of thought and practice, becomes possible only when the sacred has a material presence, a material place.

That is why all Protestants, some Buddhists, and Jews opposed pilgrimage to the Holy Land, viewing it as a form of idolatry. (p. 90)

Pilgrimage is not a sport.

Another difference from sports is that pilgrims often impose hardships on themselves, but the purpose of pilgrimage is often healing (to cure one's own illness or that of a loved one).

In sports, preparation is as thorough as possible, whereas in pilgrimage, preparation is as lax as possible (p. 96).

She wanted to convey a political message by borrowing the religious form of pilgrimage.

While pilgrimage was traditionally associated with healing the illnesses of the pilgrim or his loved ones, she saw war, violence, and hatred as plagues that were ruining the world.

The political message that fueled her pilgrimage, and the way she sought healing and transformation—not by appealing to God, but by inspiring fellow human beings—made her a forerunner of countless political pilgrims today. (p. 101)

King decided to stop making demands on the oppressed and instead appeal to all the people of the world.

This was the strategy of the Birmingham struggle, which could be said to be the most important event in the black civil rights movement.

The first march began on Good Friday 1962, and countless others have followed.

The Birmingham struggle produced some very famous photographs.

Photos of people being doused with water bombs from high-pressure fire hoses and attacked by police dogs have sparked outrage around the world.

Hundreds of protesters, including King, were arrested for walking through Birmingham. (p. 103)

? Labyrinths and Cruises: This book demonstrates the intimate relationship between the physical act of walking and writing and reading, drawing on examples of stories that can only be read on foot, such as the paintings on cars used in cruising (a Latin American youth practice of driving at a strolling pace while flirting or picking fights), the meaning of labyrinths and labyrinths, and religious statues in gardens and monastery cloisters.

Modified cars are not only works of art, but also a modern version of the paseo or corso, a traditional Spanish-Latin American practice of strolling through a public square.

For hundreds of years, strolling through city squares has been a social custom in Spain and Latin America.

[… … ] A plaza walk is a type of walking that emphasizes slow, deliberate movement, social interaction, and self-expression, and is not a way of going somewhere, but a way of being somewhere.

Whether walking or driving, the route of a plaza stroll is essentially circular. (p. 113)

Mazes and labyrinths are stories that can be read with both eyes and walked into with both feet, that is, stories that can be occupied by the body.

Just as there are similarities between symbolic paths like the Stations of the Cross or the Labyrinth, there are similarities between all stories and all paths.

One of the unique characteristics shared by all paths—wide and narrow, mountain paths, forest paths, and so on—is that it is impossible to fully grasp them without walking them firsthand. (p. 121)

There is a special relationship between a story and a journey.

That may be why writing a story is so closely related to walking.

Writing is about creating new paths in imaginary territory, or pointing out new aspects on familiar paths.

Reading is following the guide, the author.

We may not always agree with him or trust him, but one thing is certain: our guide will take us somewhere. (p. 122)

The Renaissance gardens were filled with elaborately arranged statues of figures from mythology and history.

Because these were well-known stories, no further text was needed, but walking through the garden and admiring the statues was like recalling a familiar story, a retelling of a familiar story. (p. 126)

? The Fashion of Nature, From Gardens to Parks: One of the virtues of this book is that it historicizes seemingly natural sensibilities and values, showing specifically the context and people behind their creation.

This is also a virtue made possible by a marginalized perspective that does not mythologize formalized history.

The desire to walk in nature throughout history is a combination of beliefs and tastes that have developed over 300 years.

As English gardens embraced 'naturalism' as the latest trend, private gardens and walking paths gradually became public spaces, and parks and fields were also created.

Furthermore, this sentiment acquired a more powerful political force during Wordsworth's time, when he forged a close relationship between childhood, nature, and democracy.

Just as the 12th-century Cultural Revolution produced romantic love and presented it as a literary theme, the 18th-century Cultural Revolution produced and presented natural tastes.

[… … ] The impact of the 18th century cultural revolution on tastes for nature and walking cannot be overemphasized.

The 18th-century Cultural Revolution reshaped both the spiritual and the physical world, sending countless travelers to remote locations and creating countless parks, nature reserves, travel routes, guidebooks, and travel groups and organizations. (p. 141)

A love of nature appreciation was a sign of refined taste, and those who desired refined taste wanted to learn how to appreciate nature.

[… … ] Natural gardens were luxurious facilities that could only be created and used by a very small number of people, but eternal nature was free for everyone.

As the roads became less dangerous and arduous, travel became more affordable, and more and more middle-class people began to enjoy travel as a hobby.

Natural taste was something to be learned, and Gilpin was a teacher to many. (p. 156)

Walking in this way was an exercise in recalling Rousseau's complex equation between virtue and simplicity, childhood and nature.

[… … ] By the end of the 18th century, Rousseau and Romanticism had established the equation that nature was emotion and emotion was democracy, and they described the social order as extremely artificial and argued that rebelling against class privilege was ‘the only thing that does not go against nature.’

[… …] Wordsworth's achievement was to take Rousseau's task and develop it further, elucidating the relationship between childhood, nature, and democracy, but instead of proving it logically, he depicted it with images. (p. 180)

In England, walking, whether long or short, is an act of philosophical radicalism, an expression of unconventionality, a desire to recognize the poor and to identify with them (p. 179).

? Pedestrian literature and mountaineering literature: Nature, which became an artistic religion in the 18th century and a radical religion in the late 18th century, established itself as a religion of intermediate practices in the mid-19th century.

Solnit outlines the emergence of a full-fledged travel literature as a middle-class pastime, from John Muir to more recent works.

We also cover hiking, a slightly more strenuous version of walking.

The author explains that although the relationship between mountaineering and literature is old in the East, the emergence of mountaineering in the modern sense came about because Romanticism brought back the worship of nature.

The images of walking and climbing created by this literature inspired people to assert their right to walk and to form organizations to enforce that right.

The walking essay was a genre that praised physical and mental freedom, not a genre that revolutionarily opened up a free world.

The revolution had already happened.

What the pedestrian essay did was to tame that revolution by describing how much freedom could be allowed. (p. 200)

The reason I gave these walking writers the title of gentlemen is because they all seem to be members of a walking club.

It doesn't mean that there actually is such a walking club, but it means that they share similar backgrounds.

They are generally privileged (English writers seem to write as if they assume their readers are all Oxford or Cambridge graduates, and even Thoreau in America was a Harvard graduate), have a faintly clerical bent, and are predominantly male.

As is clear from the passages quoted above, they are neither dancing country girls nor young women with narrow strides.

When they leave, what they leave behind is their wife and children, not their husbands. (p. 202)

It is impurity that makes walking an important act.

When walking becomes impurely intertwined with landscapes, thoughts, and encounters, the walking body becomes a medium connecting the mind and the world.

And when that happens, the world seeps into your heart.

Books like this one ironically illustrate how easy it is for the topic of walking to slip into other topics, and how it's difficult to focus on walking itself while neglecting other things.

Writing about walking—about the character of the person walking, the people they meet along the way, the nature they see along the way, and the things they accomplish along the way—is often writing about something else.

There are many articles that start out as stories about walking and then turn into completely different stories.

But the history of the reasons we walk this land, and the winding 200-year history, is composed of the aforementioned walking essays and canonical travel literature. (p. 217)

As previously argued, if walking is a microcosm of life, then mountaineering is a more dramatic microcosm of life.

Mountaineering is more dangerous, death is closer, and the outcome is more uncertain.

Also, mountaineering has a clearer concept of arrival, and the sense of accomplishment upon arrival is greater. (p. 225)

The history of mountaineering is littered with firsts, greatests, and disasters, but behind the dozens of famous climbers who have made it to such milestones are countless climbers who have been content with purely personal rewards.

History rarely contains archetypes, and archetypes (though they may often be expressed in literature) are rarely expressed in history.

This binary opposition is reflected to some extent in two genres of mountaineering books.

The two genres are mountaineering epics, widely read by the general public, and mountaineering memoirs, which seem to have a much smaller readership. (p. 235)

Organizing a group for walking may seem odd at first glance.

Indeed, the independence, solitude, and freedom often mentioned by those who value walking come from the absence of organization and control.

But to get out and enjoy walking, three conditions must be met.

Free time, free space to walk, a body free from disease or social constraints.

This fundamental freedom has been the object of countless struggles.

It's only natural that workers' groups, having fought hard to secure free time (eight or ten hours, and then a five-day workweek), would fight to secure a place to spend that time. (p. 273)

Walking in the City: With the emergence of modern metropolises, the anonymity, diversity, and hybridity that cities offer have become increasingly prominent.

While the city offers a wealth of new possibilities for the urban stroller, who strolls between its streets, high-rise buildings, and its numerous cafes, bars, and shops, it is also a place fraught with the dangers of crime, poverty, and sanitation.

Solnit emphasizes that freely walking through and experiencing the city's public spaces, which harbor such imbalances, is not only a creative way to utilize the inspiration the city provides, but also a key element of one's right to participate in public life and, furthermore, a key element of one's life as a citizen.

Along with this, what the author focuses on is the fact that freely moving around urban spaces is subject to restrictions due to race, class, religion, ethnicity, and sexual orientation.

This difference is revealed, for example, in how the New York streets depicted in the poetry of James Baldwin, a black gay poet, differ from those of other gay poets active in New York at the same time, such as Whitman and Ginsberg.

Urban walking can easily devolve into activities like soliciting, cruising, strolling, shopping, rioting, protesting, running away, and wandering—activities that, however enjoyable, rarely convey a lofty moral resonance like a love of nature.

So few people argued for the protection of urban space, and even the few liberals and urban theorists who did were largely unaware that walking was the most common way to use and inhabit public spaces. (p. 281)

But if public spaces disappear, then ultimately publicness also disappears.

It also becomes impossible for individuals to become citizens, that is, to experience and act together with their fellow citizens.

To become a citizen, you must have the awareness that you are with people you don't know.

Isn't the foundation of democracy trust in those who don't know?

A public place is a place where you can interact with strangers without discrimination.

It is through these communal events that the abstract concept of publicness becomes concrete reality. (p. 348)

Only citizens who are adept at making their city their territory (both symbolic and actual), and citizens who are accustomed to walking around their city with others, can plan a rebellion.

The First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution guarantees the “right of the people peaceably to assemble in one place,” along with freedom of the press, freedom of speech, and freedom of religion, as essential rights for democracy, but few people remember that fact.

While violations of other rights are easily recognized, factors that block the possibility of assembly, such as car-centric urban design and deteriorating pedestrian environments, are difficult to trace causally and rarely emerge as civil rights issues.

But if public spaces disappear, then ultimately publicness also disappears.

It also becomes impossible for individuals to become citizens, that is, to experience and act together with their fellow citizens.

To become a citizen, you must have the awareness that you are with people you don't know.

Isn't the foundation of democracy trust in those who don't know?

A public place is a place where you can interact with strangers without discrimination.

It is through these communal events that the abstract concept of publicness becomes concrete reality. (p. 351)

In the section on gay poets in New York, Harlem-born James Baldwin was not mentioned.

Unlike Whitman or Ginsberg, for Baldwin Manhattan was not a place of sweet liberation, but a threatening place that constantly reminded him of his reality.

[… … ] They were all threatening to him.

He was both a gay man and a black man, but the urban pedestrians he wrote about were black men rather than gay men (p. 388).

? Women's Walking (Walking with Sex): This book particularly addresses the issue of women's inability to safely and freely enjoy the city streets and nights, namely, the possibility of women entering public space.

This is because moving around and using public spaces without restrictions is directly related to the issue of leading a public life as a citizen.

Through the writings of Virginia Woolf and Sylvia Plath, we discuss women's experiences in public spaces, and analyze the meaning of George Sand's choice of cross-dressing as a means of navigating the city.

The places where feminism has demanded and achieved reforms have primarily been in the interpersonal relationships within the home (home, workplace, school, political organizations).

However, access to public spaces for social, political, practical and cultural purposes is also an important part of everyday life, both in rural and urban areas.

However, this access is limited for women.

Because there is a fear of assault and harassment. (p. 384)

I suddenly realized that if I go outside, I lose my right to live, my right to be free, my right to pursue happiness. There are so many people in this world who hate me and want me to suffer just because I am a woman, even though I am a complete stranger to them. Sex can easily turn into violence. I realized that almost no one else sees this situation as a public issue rather than a private one.

It was the most shocking realization of my life. (p. 386)

All kinds of advice poured in.

Don't go out at night, wear loose clothing, wear a hat or cut your hair short, act like a man, move to an expensive neighborhood, take a taxi, buy a car, don't walk alone, get a man to escort you.

A modern Greek stone wall.

A modern-day Assyrian veil.

These were pieces of advice that said it was not society's responsibility to protect my freedom, but rather I was responsible for controlling my own actions and the actions of men. (p. 386)

Throughout the history of walking, the main figures have all been men.

[… … ] It was when Sylvia Plath was nineteen that she wrote down the reason in her diary.

“It is my terrible tragedy to be born a woman.

I desperately want to mingle with the workers on the road, the sailors and soldiers, the bar patrons, to be part of the landscape, to be anonymous, to listen, to record, but it's all gone.

Because I am a young woman.

Because females are more likely to be attacked or beaten by males.

How great would it be if we could have as deep a conversation as possible with everyone?

How nice it would be if we could sleep in the open air.

How wonderful it would be if I could travel west.

“How nice it would be if we could walk around freely at night.” (p. 374)

George Sand, one of the urban explorers, disguised herself as a man and joined the ranks of urban explorers.

Wearing men's clothes for the first time, she indulged in the feeling of freedom of movement.

“I can’t say enough good things about my new boots.

[… … ] A small iron was driven into the rear axle, allowing the feet to be firmly planted on the pavement.

I wandered around Paris from one end to the other.

It seemed like I might go on a trip around the world.

The clothes I was wearing were equally sturdy.

“I went out regardless of the weather, came home regardless of the time, and bought floor seats regardless of the theater.” (p. 329)

March, Festival, Revolution: This book shows how the streets, where citizens walk together, become the greatest stage for democracy, and explores the political significance of walking.

Solnit connects the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, the Velvet Revolution in Czechoslovakia, the May Square Mothers, a group of women with no political experience who walked together for years to raise awareness of the children who had disappeared under the military regime and leave their personal memories in history, and the achievements of the anti-war and anti-nuclear protests in which the author herself participated, into a "history written by two feet."

The city was being reorganized from a place centered on business and vehicles to a place centered on the pedestrian movement of people on the streets—the most physical form of freedom of speech.

The street was being transformed from a path leading to indoor spaces such as homes, schools, offices, and shops into a giant amphitheater.

If you think about why people protested and marched in the first place, it's probably because those times were the only times when the streets of American cities were perfectly pedestrian-friendly.

There's no need to worry about being hit by a car or being wary of strangers. (pp. 365-366)

The market women's march through Versailles was a case where the ordinary gestures of ordinary citizens became history.

The moment when thousands of women walked to Versailles was the moment when the past of obedience to all authority was overcome, and the future that would leave behind trauma had not yet begun.

That day, the world was on their side.

They were not afraid of anything. (p. 357)

Halloween on Castro Street is also a mixed event.

Although it is a commemorative event, it also began as a political statement.

Because declaring one's queer identity is in itself a bold political statement.

Proclaiming a queer identity is a spirited subversion of the long-held tradition that sexuality is secretive and homosexuality shameful.

In times of alienation, gathering itself is a rebellion, just as in times of boredom, isn't joy itself a rebellion? (p. 344)

Most parades or marches are held to commemorate something.

As we walk through the city to commemorate the past, time and place are connected, past memories and future possibilities are connected, and the city and its citizens are connected, creating a commemorative space where a living whole, a history, can be created.

This means that the past is the cornerstone of the future, and that if you do not know how to honor the past, you cannot create the future. (pp. 346-347)

The Crisis of Walking: The crisis of walking is a crisis of public space, a crisis of analog, a crisis of speculative thought, and a crisis of democracy.

Solnit points out what we're losing as we increasingly push walking out of our daily lives, citing the suburbanization of cities and the reduction of exercise to treadmills.

In ecological terms, walking could be considered an 'indicator species'.

Indicator species are indicators of ecosystem health, and when indicator species become endangered, decline, or become endangered, it is an early warning sign that something is wrong with the ecosystem.

Walking is an indicator of the ecosystem of freedom and joy: free time, a wonderful, open space, and an unconstrained body (p. 400).

As cars encourage the fragmentation and privatization of space, shopping malls replace shopping districts, public spaces become buildings floating on a sea of asphalt, and urban design becomes nothing more than traffic engineering.

People gathering together in one place is becoming less and less free and rare.

While the street is a public place where the freedom of speech and assembly guaranteed by the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution applies, a shopping mall is not such a public place.

If democratic and liberating possibilities arise when people gather in public spaces, those possibilities are absent for those who live in places where there is nowhere to gather. (p. 408)

Just as factories didn't produce more quickly and thus shorten working hours, vehicles didn't travel faster and thus shorten the amount of time people spent in their cars.

Instead, people are forced to travel longer distances more frequently (for example, Californians now spend three to four hours each day commuting). People are less likely to walk because there are fewer places to walk, but also because they have less time to walk.

The free and uninhibited space and time of contemplation, where thoughts, romance, dreams, and sights unfolded, has now disappeared.

Machines are getting faster, and life is trying to keep up with them. (p. 414)

Casinos and Clark County officials are exploring privatizing sidewalks, Peck said, to provide grounds for prosecuting or evicting anyone engaging in activities protected by the First Amendment (such as religious, sexual, political, or economic speech) or who in any way disrupts the pleasant tourist experience. (Similarly, Tucson officials are currently considering privatizing sidewalks by renting them out to street vendors for $1, with the goal of driving homeless people off the sidewalks.) (pp. 453-454)

Efforts to control who walks and how they walk reveal that walking can still be a subversive act in some ways.

At the very least, walking subverts the ideals of thoroughgoing spatial privatization and mass control, offering entertainment that requires no expense, entertainment that is not consumption (pp. 456-457).

The same goes for the meadow of imagination.

Spending time there is not work, but without it the human mind becomes barren, dull, and tame.

The struggle to secure free spaces—untamed spaces and public spaces—must be accompanied by a struggle to secure the free time to wander through those spaces. (pp. 463-464)

I am always overwhelmed by the writing, crafted with courageous language cultivated from the field, the insight of someone who has observed for a long time, a solid intellect built with sincerity, and a beautiful emotion that spreads between each line like a sunset.

After reading 『The Humanities of Walking』, I can guess a little bit about the secret.

I think the driving force behind this was walking, “recognizing the world through the body and recognizing the body through the world.”

This expanding text proves that the mere act of pushing one's body, the arduous act of walking, can transform someone into an environmental activist, a philosopher, a feminist, an artist, a meditator.

In proving it, Solnit becomes all of that being.” - Eunyu (author)

“Through this book, I realized that I have a wonderful weapon that no one can take away from me.

I think while walking, I dream of communicating with something other than myself while walking, I get new ideas while walking, and by walking, I am clearly different from before I started walking.

Rebecca Solnit testifies brilliantly in this book.

“The power of human beings to become a little different each time they walk, thinking more, longer, and more deeply.” - Jeong Yeo-ul (literary critic)

“Walking, as Rebecca Solnit says, means sending this world to a higher and farther place, that is, ‘progress.’

All over the world, people are walking to bridge the gap between race and gender.

“This is why we hear the history of hope in the voice of Rebecca Solnit, who tells the history of walking.” - Kim Yeon-su (novelist)

A letter of respect and solidarity from world-renowned intellectual Rebecca Solnit to Korean readers.

It was inspiring and awe-inspiring to see Koreans unite against an unjust regime last year.

But those on the other side of the world who knew our history were not surprised.

One of the themes of this book is that unarmed citizens walking out into public space are a tremendous force, sometimes a force for self-government, and sometimes a force to stop oppressive and rogue regimes.

[… … ] Democracy is often an experience.

It is the experience of physically coming together in a public space, the experience of seeing with our own eyes, the experience of not stepping back, the experience of walking until we reach our goal.

It is the greatest and most beautiful experience of power in the world where people live.

As the author, I am honored that this book is published in a country where the power of citizens to defend justice and freedom is being demonstrated in many ways, from the anti-globalization movement to recent events. - Rebecca Solnit, "To Korean Readers"

Rebecca Solnit, author of 'Mansplaining' and one of the '25 Thinkers Who Will Change Your World' by UtterLitter in 2010.

Solnit's writings also receive deep sympathy and support from Korean readers.

『Men Keep Trying to Teach Me』 and 『Far and Close』, published in Korea in 2015 and 2016 respectively, were named as books of the year by numerous media outlets.

In addition to 『Men Keep Trying to Educate Me』, which made Rebecca Solnit most famous, she is already known in Korea for books such as 『Gaze into These Ruins』 and 『Hope in the Darkness』, which highlighted her as an activist, and 『Far Away, Yet Close』, which highlighted her as an essayist. However, this book is more special as the starting point and comprehensive edition of Solnit's unique thoughts and methodology.

This is also why many writers and readers have been waiting for the publication of this book for a long time.

What makes this book even more special is the letter of respect, empathy, and solidarity that Rebecca Solnit sent to her Korean readers (and the author's unusually generous preface to the Korean edition).

Solnit, who was deeply impressed by the democratic achievements made by millions of citizens in the squares from the fall of 2016 to the spring of 2017, says she discovered another reason why "The Humanities of Walking" is still relevant nearly 20 years after its publication.

This is the 'power of unarmed citizens walking out into public space,' which is also the main theme of this book.

Through the preface to the Korean edition, which beautifully and clearly recreates the "experience of the greatest and most beautiful power," the author once again conveys a profound sense of emotion to the citizens of Korea.

Deep thought and captivating writing: the essence of Rebecca Solnit's essays.

A model for humanistic essays encompassing history, philosophy, politics, literature, and art criticism.

If we were to categorize Rebecca Solnit's books by another criterion, they would fall into two categories.

A book of short, poetic essays, written in one breath from beginning to end.

And among the latter, this book is the one that focuses most densely on a single topic.

Solnit seamlessly weaves together traditional methodologies from the humanities—history, philosophy, politics, literature, and art criticism—while also incorporating personal experience to create a richer journey. The author wrote this book not only through textual research and verification, but also through walking and experiencing it firsthand.

This book comprehensively covers almost every element and aspect of walking, including people walking and their gatherings, places where people walk, the forms and types of walking, literature and art that depict walking, the structure and evolution of the walking body, and the social conditions that allow for free walking. Ultimately, it speaks to the meaning and possibilities that the act of walking holds for humans, and is, in short, a model humanistic essay.

The numerous historical figures, canonical texts, ideas, and events covered in 『The Humanities of Walking』 are thoroughly digested by the author, and then interpreted and reconstructed with a comprehensive meaning.

Through this book, we explore the mind vs.

Physical, Private vs.

Public, City vs.

Rural, Private vs.

We can find a completely new answer to traditional philosophical motifs such as the group, digested in Solnit's style, without excluding the perspectives and voices of minorities.

The History of Walking and the Crisis of Walking

? The Meaning of Walking: Solnit presents compelling arguments for why walking should be a subject of humanistic inquiry.

Walking is an activity that is far removed from a production-oriented culture, and is an activity that is both a means and an end in itself.

This is a characteristic that applies equally to the humanities.

According to Solnit, the best way to reflect on your mind is to walk.

This entire book can be said to be a process of proving that “the history of walking embodies the history of thought.”

“Discovering a completely new perspective is a great happiness, and I can experience this happiness at any time even now.” (p. 19)

In a production-oriented culture, thinking is often seen as doing nothing, but doing nothing is not easy.

The best way to do nothing is to pretend to do something, and the closest thing to doing nothing is to walk.

Among the intentional actions of humans, walking is the one closest to the involuntary rhythm of the body (breathing, heartbeat).

Walking is a delicate balance between working and not working, between just being and doing something.

Could it be said that it is physical labor that produces nothing but thoughts, experiences, and arrivals? (p. 20)

Walking is both a means and an end, a journey and a destination. (p. 22)

The reason I like walking is because it's slow.

I think the mind has a similar speed to the two feet (less than 5 kilometers per hour).

If that idea is correct, then the pace at which modern life moves is faster than the pace at which thoughts move (p. 28).

To identify a place is to plant invisible seeds of memory and association in that place.

When you return to that place, the fruit of that seed awaits you.

New places mean new ideas, new possibilities.

Exploring the world is the best way to explore your mind.

Just as you must walk to see the world, you must walk to see your heart. (p. 32)

Walking and Philosophers: While Greek philosophers are often invoked to explain the close relationship between walking and thinking, Solnit points out that this was also the setting for Rousseau and his contemporaries.

It is true that the Greeks walked a lot, and that the names of the Stoics and the Peripatetics are related to walking, but it was Rousseau who first linked philosophical thinking to walking.

Solnit emphasizes that the unique and powerful thinking of Rousseau and Kierkegaard, and their characteristics as "hybrid philosophers and philosophical writers," is due to the works they wrote while walking.

The history of walking is longer than the history of humans.

However, if we consider walking as a kind of conscious cultural act rather than simply a means, the history of walking can be said to have begun in Europe only a few centuries ago.

And Rousseau is at its origin.

Its history was created by the feet of various people in the 18th century, but among them, the more scholarly ones sought to create a great tradition of walking by tracing the origins of walking to ancient Greece.

It was a time when Greek customs were both joyfully worshipped and distorted. (p. 33)

If Rousseau's writings are the precursor to the literature dealing with philosophical gait, it is because he was one of the first writers to consider it worthwhile to record in detail the circumstances in which his reflections took place.

If Rousseau was a radical, his most radical act was to reassess the value of personal, private experience (based on walking, solitude, and nature). (p. 45)

“I think the only time I could think that much, exist that much, experience that much, and become that much myself was when I was traveling alone on foot.

Walking on two feet energizes and refreshes my mind.

Should we say that if we stay in one place, our head won't work properly? Should we say that if our body moves, our mind will move too?

The countryside, the pleasant prospects that continue, the fresh air, the good appetite, the health that walking improves, the casual atmosphere of the tavern, the absence of anything that reminds me of my subjugation and my miserable situation.

All this frees my soul from its bonds, gives me more courage to think, and allows me to immerse myself in the vast ocean of beings.

“Thanks to this, I can freely combine, select, and utilize those beings without any discomfort or fear.” (p. 41)

Unlike the rigid format of a thesis, or the chronological format of a biography or history, the travelogue encourages digression and association.

Nearly a century and a half after Rousseau's death, James Joyce and Virginia Woolf, seeking to portray the workings of the mind, developed a style called stream of consciousness.

In Joyce's novel Ulysses and Woolf's novel Mrs. Dalloway, the jumbled thoughts and memories in the protagonists' heads are best resolved when they are walking down the street.

In other words, the type of thinking that best suits the non-analytical, spontaneous act of walking is this non-systematic, associative type of thinking.

Rousseau's "Reveries of a Solitary Walker" is one of the first paintings to illustrate this relationship between thought and walking. (p. 44)

? Evolutionary Perspectives, The Science of Walking: Through paleoanthropological discussions surrounding walking, this book examines the evolutionary impact of upright walking on the human body and society, and refutes the white-centric, patriarchal ideology that permeates evolutionary history.

British experts who had cheered Piltdown Man doubted that the child, named Taung Child, was an ancestor of mankind.

Scientists of that era were reluctant to accept the idea that their ancestors were African, and they were reluctant to accept evidence that they once walked on two legs while having small brains—evidence that our intelligence had come later, not earlier, in our evolution. (p. 65)

In current discussions, upright walking is the Rubicon that our evolving species crossed to become completely distinct from other primates.

We've achieved many wonderful results with upright walking.

Arches resembling Gothic architecture appeared on the body, and the entire body became longer up and down.

Starting from the bottom, the toes point in one direction, creating an arch on the inside of the foot.

As both legs are stretched out, the gluteus maximus is developed convexly.

The stomach became flat, the waist became flexible, the spine became straight, the shoulders lowered, the neck became longer, and the head was held upright.

When you look at a body standing upright, each part is exquisitely balanced, like a pillar. (Page 66)

There is a widespread belief in the human evolution literature that women are clumsier walkers.

The belief that women have brought a fatal curse upon the entire human species, that women have been merely helpers to men in the evolutionary process, and that walking is related to thinking, so women are bound to lack thinking, seem to be yet another relic left behind by Genesis.

If humans gained the freedom to go places they had never been before, to do things they had never done before, and to think freely when they learned to walk, women's freedom was often linked to sexuality, or more precisely, to a sexuality that required control and containment.

But such discussions are no longer about physiology but about ethics. (p. 78)

Scientists who talk about walking and evolution have one important point to make, no matter how far-fetched their claims may be.

It attempts to discuss the essential meaning of walking—in other words, it asks not what we make of walking, but what walking has made of us. (p. 79)

? Pilgrimage: This book explores the significance of pilgrimage as a "self-inflicted walk" in human history, encompassing experiences of pilgrimage to the Chimayo Shrine, the writings and lives of anti-war activists known as "Peace Pilgrims," and the Birmingham March, where Martin Luther King Jr. transformed traditional pilgrimage into a civil rights movement action.

If embarking on a pilgrimage is an expression of the soul's faith and hope through bodily movements, isn't pilgrimage an act of reconciling spirit and matter?

The idea that pilgrimage is a union of faith and action, of thought and practice, becomes possible only when the sacred has a material presence, a material place.

That is why all Protestants, some Buddhists, and Jews opposed pilgrimage to the Holy Land, viewing it as a form of idolatry. (p. 90)

Pilgrimage is not a sport.

Another difference from sports is that pilgrims often impose hardships on themselves, but the purpose of pilgrimage is often healing (to cure one's own illness or that of a loved one).

In sports, preparation is as thorough as possible, whereas in pilgrimage, preparation is as lax as possible (p. 96).

She wanted to convey a political message by borrowing the religious form of pilgrimage.

While pilgrimage was traditionally associated with healing the illnesses of the pilgrim or his loved ones, she saw war, violence, and hatred as plagues that were ruining the world.

The political message that fueled her pilgrimage, and the way she sought healing and transformation—not by appealing to God, but by inspiring fellow human beings—made her a forerunner of countless political pilgrims today. (p. 101)

King decided to stop making demands on the oppressed and instead appeal to all the people of the world.

This was the strategy of the Birmingham struggle, which could be said to be the most important event in the black civil rights movement.

The first march began on Good Friday 1962, and countless others have followed.

The Birmingham struggle produced some very famous photographs.

Photos of people being doused with water bombs from high-pressure fire hoses and attacked by police dogs have sparked outrage around the world.

Hundreds of protesters, including King, were arrested for walking through Birmingham. (p. 103)

? Labyrinths and Cruises: This book demonstrates the intimate relationship between the physical act of walking and writing and reading, drawing on examples of stories that can only be read on foot, such as the paintings on cars used in cruising (a Latin American youth practice of driving at a strolling pace while flirting or picking fights), the meaning of labyrinths and labyrinths, and religious statues in gardens and monastery cloisters.

Modified cars are not only works of art, but also a modern version of the paseo or corso, a traditional Spanish-Latin American practice of strolling through a public square.

For hundreds of years, strolling through city squares has been a social custom in Spain and Latin America.

[… … ] A plaza walk is a type of walking that emphasizes slow, deliberate movement, social interaction, and self-expression, and is not a way of going somewhere, but a way of being somewhere.

Whether walking or driving, the route of a plaza stroll is essentially circular. (p. 113)

Mazes and labyrinths are stories that can be read with both eyes and walked into with both feet, that is, stories that can be occupied by the body.

Just as there are similarities between symbolic paths like the Stations of the Cross or the Labyrinth, there are similarities between all stories and all paths.

One of the unique characteristics shared by all paths—wide and narrow, mountain paths, forest paths, and so on—is that it is impossible to fully grasp them without walking them firsthand. (p. 121)

There is a special relationship between a story and a journey.

That may be why writing a story is so closely related to walking.

Writing is about creating new paths in imaginary territory, or pointing out new aspects on familiar paths.

Reading is following the guide, the author.

We may not always agree with him or trust him, but one thing is certain: our guide will take us somewhere. (p. 122)

The Renaissance gardens were filled with elaborately arranged statues of figures from mythology and history.

Because these were well-known stories, no further text was needed, but walking through the garden and admiring the statues was like recalling a familiar story, a retelling of a familiar story. (p. 126)

? The Fashion of Nature, From Gardens to Parks: One of the virtues of this book is that it historicizes seemingly natural sensibilities and values, showing specifically the context and people behind their creation.

This is also a virtue made possible by a marginalized perspective that does not mythologize formalized history.

The desire to walk in nature throughout history is a combination of beliefs and tastes that have developed over 300 years.

As English gardens embraced 'naturalism' as the latest trend, private gardens and walking paths gradually became public spaces, and parks and fields were also created.

Furthermore, this sentiment acquired a more powerful political force during Wordsworth's time, when he forged a close relationship between childhood, nature, and democracy.

Just as the 12th-century Cultural Revolution produced romantic love and presented it as a literary theme, the 18th-century Cultural Revolution produced and presented natural tastes.

[… … ] The impact of the 18th century cultural revolution on tastes for nature and walking cannot be overemphasized.

The 18th-century Cultural Revolution reshaped both the spiritual and the physical world, sending countless travelers to remote locations and creating countless parks, nature reserves, travel routes, guidebooks, and travel groups and organizations. (p. 141)

A love of nature appreciation was a sign of refined taste, and those who desired refined taste wanted to learn how to appreciate nature.

[… … ] Natural gardens were luxurious facilities that could only be created and used by a very small number of people, but eternal nature was free for everyone.

As the roads became less dangerous and arduous, travel became more affordable, and more and more middle-class people began to enjoy travel as a hobby.

Natural taste was something to be learned, and Gilpin was a teacher to many. (p. 156)

Walking in this way was an exercise in recalling Rousseau's complex equation between virtue and simplicity, childhood and nature.

[… … ] By the end of the 18th century, Rousseau and Romanticism had established the equation that nature was emotion and emotion was democracy, and they described the social order as extremely artificial and argued that rebelling against class privilege was ‘the only thing that does not go against nature.’

[… …] Wordsworth's achievement was to take Rousseau's task and develop it further, elucidating the relationship between childhood, nature, and democracy, but instead of proving it logically, he depicted it with images. (p. 180)

In England, walking, whether long or short, is an act of philosophical radicalism, an expression of unconventionality, a desire to recognize the poor and to identify with them (p. 179).

? Pedestrian literature and mountaineering literature: Nature, which became an artistic religion in the 18th century and a radical religion in the late 18th century, established itself as a religion of intermediate practices in the mid-19th century.

Solnit outlines the emergence of a full-fledged travel literature as a middle-class pastime, from John Muir to more recent works.

We also cover hiking, a slightly more strenuous version of walking.

The author explains that although the relationship between mountaineering and literature is old in the East, the emergence of mountaineering in the modern sense came about because Romanticism brought back the worship of nature.

The images of walking and climbing created by this literature inspired people to assert their right to walk and to form organizations to enforce that right.

The walking essay was a genre that praised physical and mental freedom, not a genre that revolutionarily opened up a free world.

The revolution had already happened.

What the pedestrian essay did was to tame that revolution by describing how much freedom could be allowed. (p. 200)

The reason I gave these walking writers the title of gentlemen is because they all seem to be members of a walking club.

It doesn't mean that there actually is such a walking club, but it means that they share similar backgrounds.

They are generally privileged (English writers seem to write as if they assume their readers are all Oxford or Cambridge graduates, and even Thoreau in America was a Harvard graduate), have a faintly clerical bent, and are predominantly male.

As is clear from the passages quoted above, they are neither dancing country girls nor young women with narrow strides.

When they leave, what they leave behind is their wife and children, not their husbands. (p. 202)

It is impurity that makes walking an important act.

When walking becomes impurely intertwined with landscapes, thoughts, and encounters, the walking body becomes a medium connecting the mind and the world.

And when that happens, the world seeps into your heart.

Books like this one ironically illustrate how easy it is for the topic of walking to slip into other topics, and how it's difficult to focus on walking itself while neglecting other things.

Writing about walking—about the character of the person walking, the people they meet along the way, the nature they see along the way, and the things they accomplish along the way—is often writing about something else.

There are many articles that start out as stories about walking and then turn into completely different stories.

But the history of the reasons we walk this land, and the winding 200-year history, is composed of the aforementioned walking essays and canonical travel literature. (p. 217)

As previously argued, if walking is a microcosm of life, then mountaineering is a more dramatic microcosm of life.

Mountaineering is more dangerous, death is closer, and the outcome is more uncertain.

Also, mountaineering has a clearer concept of arrival, and the sense of accomplishment upon arrival is greater. (p. 225)

The history of mountaineering is littered with firsts, greatests, and disasters, but behind the dozens of famous climbers who have made it to such milestones are countless climbers who have been content with purely personal rewards.

History rarely contains archetypes, and archetypes (though they may often be expressed in literature) are rarely expressed in history.

This binary opposition is reflected to some extent in two genres of mountaineering books.

The two genres are mountaineering epics, widely read by the general public, and mountaineering memoirs, which seem to have a much smaller readership. (p. 235)

Organizing a group for walking may seem odd at first glance.

Indeed, the independence, solitude, and freedom often mentioned by those who value walking come from the absence of organization and control.

But to get out and enjoy walking, three conditions must be met.

Free time, free space to walk, a body free from disease or social constraints.

This fundamental freedom has been the object of countless struggles.

It's only natural that workers' groups, having fought hard to secure free time (eight or ten hours, and then a five-day workweek), would fight to secure a place to spend that time. (p. 273)

Walking in the City: With the emergence of modern metropolises, the anonymity, diversity, and hybridity that cities offer have become increasingly prominent.

While the city offers a wealth of new possibilities for the urban stroller, who strolls between its streets, high-rise buildings, and its numerous cafes, bars, and shops, it is also a place fraught with the dangers of crime, poverty, and sanitation.

Solnit emphasizes that freely walking through and experiencing the city's public spaces, which harbor such imbalances, is not only a creative way to utilize the inspiration the city provides, but also a key element of one's right to participate in public life and, furthermore, a key element of one's life as a citizen.

Along with this, what the author focuses on is the fact that freely moving around urban spaces is subject to restrictions due to race, class, religion, ethnicity, and sexual orientation.

This difference is revealed, for example, in how the New York streets depicted in the poetry of James Baldwin, a black gay poet, differ from those of other gay poets active in New York at the same time, such as Whitman and Ginsberg.

Urban walking can easily devolve into activities like soliciting, cruising, strolling, shopping, rioting, protesting, running away, and wandering—activities that, however enjoyable, rarely convey a lofty moral resonance like a love of nature.

So few people argued for the protection of urban space, and even the few liberals and urban theorists who did were largely unaware that walking was the most common way to use and inhabit public spaces. (p. 281)

But if public spaces disappear, then ultimately publicness also disappears.

It also becomes impossible for individuals to become citizens, that is, to experience and act together with their fellow citizens.

To become a citizen, you must have the awareness that you are with people you don't know.

Isn't the foundation of democracy trust in those who don't know?

A public place is a place where you can interact with strangers without discrimination.

It is through these communal events that the abstract concept of publicness becomes concrete reality. (p. 348)

Only citizens who are adept at making their city their territory (both symbolic and actual), and citizens who are accustomed to walking around their city with others, can plan a rebellion.

The First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution guarantees the “right of the people peaceably to assemble in one place,” along with freedom of the press, freedom of speech, and freedom of religion, as essential rights for democracy, but few people remember that fact.

While violations of other rights are easily recognized, factors that block the possibility of assembly, such as car-centric urban design and deteriorating pedestrian environments, are difficult to trace causally and rarely emerge as civil rights issues.

But if public spaces disappear, then ultimately publicness also disappears.

It also becomes impossible for individuals to become citizens, that is, to experience and act together with their fellow citizens.

To become a citizen, you must have the awareness that you are with people you don't know.

Isn't the foundation of democracy trust in those who don't know?

A public place is a place where you can interact with strangers without discrimination.

It is through these communal events that the abstract concept of publicness becomes concrete reality. (p. 351)

In the section on gay poets in New York, Harlem-born James Baldwin was not mentioned.

Unlike Whitman or Ginsberg, for Baldwin Manhattan was not a place of sweet liberation, but a threatening place that constantly reminded him of his reality.

[… … ] They were all threatening to him.

He was both a gay man and a black man, but the urban pedestrians he wrote about were black men rather than gay men (p. 388).

? Women's Walking (Walking with Sex): This book particularly addresses the issue of women's inability to safely and freely enjoy the city streets and nights, namely, the possibility of women entering public space.

This is because moving around and using public spaces without restrictions is directly related to the issue of leading a public life as a citizen.

Through the writings of Virginia Woolf and Sylvia Plath, we discuss women's experiences in public spaces, and analyze the meaning of George Sand's choice of cross-dressing as a means of navigating the city.

The places where feminism has demanded and achieved reforms have primarily been in the interpersonal relationships within the home (home, workplace, school, political organizations).

However, access to public spaces for social, political, practical and cultural purposes is also an important part of everyday life, both in rural and urban areas.

However, this access is limited for women.

Because there is a fear of assault and harassment. (p. 384)

I suddenly realized that if I go outside, I lose my right to live, my right to be free, my right to pursue happiness. There are so many people in this world who hate me and want me to suffer just because I am a woman, even though I am a complete stranger to them. Sex can easily turn into violence. I realized that almost no one else sees this situation as a public issue rather than a private one.

It was the most shocking realization of my life. (p. 386)

All kinds of advice poured in.

Don't go out at night, wear loose clothing, wear a hat or cut your hair short, act like a man, move to an expensive neighborhood, take a taxi, buy a car, don't walk alone, get a man to escort you.

A modern Greek stone wall.

A modern-day Assyrian veil.

These were pieces of advice that said it was not society's responsibility to protect my freedom, but rather I was responsible for controlling my own actions and the actions of men. (p. 386)

Throughout the history of walking, the main figures have all been men.

[… … ] It was when Sylvia Plath was nineteen that she wrote down the reason in her diary.

“It is my terrible tragedy to be born a woman.

I desperately want to mingle with the workers on the road, the sailors and soldiers, the bar patrons, to be part of the landscape, to be anonymous, to listen, to record, but it's all gone.

Because I am a young woman.

Because females are more likely to be attacked or beaten by males.

How great would it be if we could have as deep a conversation as possible with everyone?

How nice it would be if we could sleep in the open air.

How wonderful it would be if I could travel west.

“How nice it would be if we could walk around freely at night.” (p. 374)

George Sand, one of the urban explorers, disguised herself as a man and joined the ranks of urban explorers.

Wearing men's clothes for the first time, she indulged in the feeling of freedom of movement.

“I can’t say enough good things about my new boots.

[… … ] A small iron was driven into the rear axle, allowing the feet to be firmly planted on the pavement.

I wandered around Paris from one end to the other.

It seemed like I might go on a trip around the world.

The clothes I was wearing were equally sturdy.