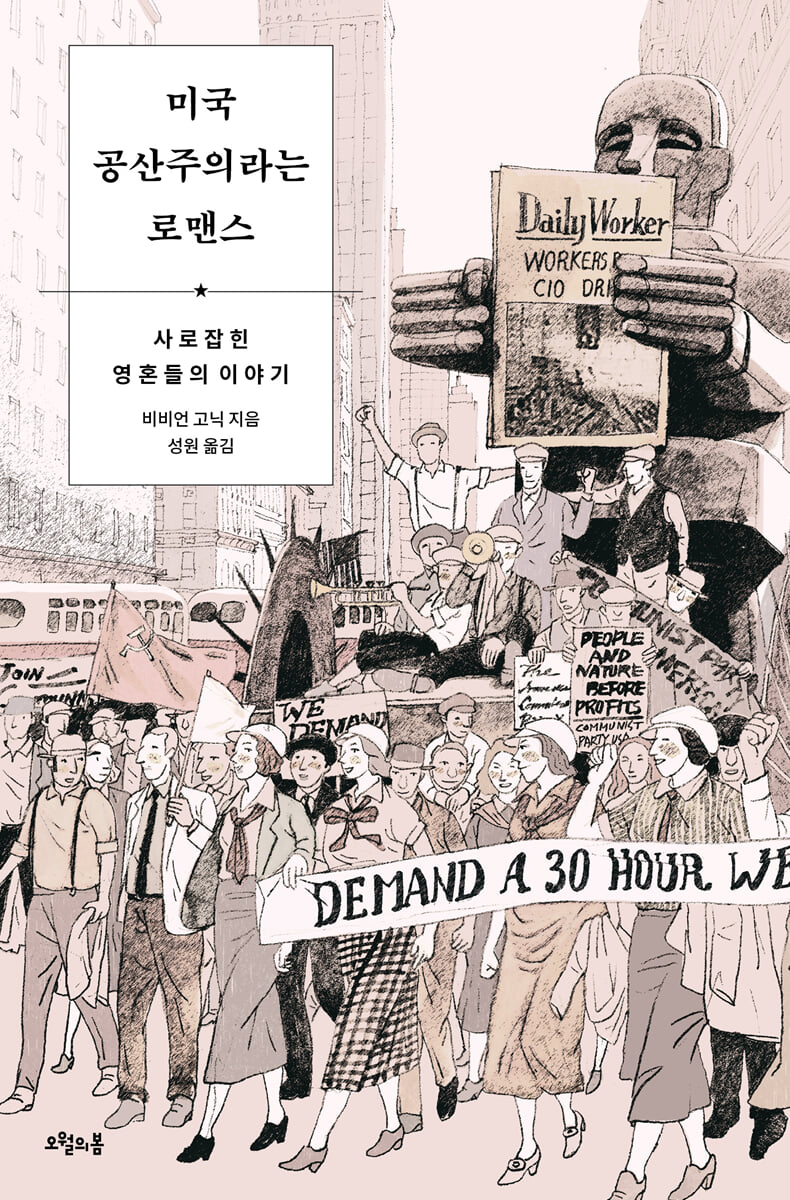

The Romance of American Communism

|

Description

Book Introduction

“I realized I was a member of the working class before I realized I was Jewish or a girl.”

One of Vivian Gornick's early works, "The Romance of American Communism," which has developed a unique style across various fields including essays, columns, criticism, and memoirs, is now available to Korean readers.

A Romance of American Communism, a record of American communists and another autobiography of the author, is a masterpiece that announced the birth of a new type of journalism and reportage literature.

This book was first published in 1977, when Vivienne Gornick was making a name for herself as a legendary journalist covering the feminist movement, and was republished in 2020 with a new foreword.

For Gonick, who has been keenly aware of his own position as a working-class Jewish immigrant throughout his life, the stigma and objectification surrounding communists was a deeply ingrained experience.

Determined to unravel this stagnation in a book, he traveled across the United States, interviewing dozens of former communists, and presented to his readers "living, flesh-and-blood" communists, those who, amidst the miserable and despicable conditions of life, had developed the most admirable passions.

His firm belief is that when we understand the vision they held, we can grasp the essence of the failures and ironies of communism.

'Romance' is a form of expression that reflects this attitude, and Gonick shows the richness of his romantic perspective by weaving his own narratives into the oral histories of his interviewees.

"The Romance of American Communism" is a rare work that unearths the past and present of "ordinary, everyday communists" amidst the vehement anti-communist literature, and is a book about individual "communists" who have been obscured in the name of system and ideology.

Furthermore, this record connects with many of today's radical social movements that question the foundation and raison d'être of 'organizations.'

One of Vivian Gornick's early works, "The Romance of American Communism," which has developed a unique style across various fields including essays, columns, criticism, and memoirs, is now available to Korean readers.

A Romance of American Communism, a record of American communists and another autobiography of the author, is a masterpiece that announced the birth of a new type of journalism and reportage literature.

This book was first published in 1977, when Vivienne Gornick was making a name for herself as a legendary journalist covering the feminist movement, and was republished in 2020 with a new foreword.

For Gonick, who has been keenly aware of his own position as a working-class Jewish immigrant throughout his life, the stigma and objectification surrounding communists was a deeply ingrained experience.

Determined to unravel this stagnation in a book, he traveled across the United States, interviewing dozens of former communists, and presented to his readers "living, flesh-and-blood" communists, those who, amidst the miserable and despicable conditions of life, had developed the most admirable passions.

His firm belief is that when we understand the vision they held, we can grasp the essence of the failures and ironies of communism.

'Romance' is a form of expression that reflects this attitude, and Gonick shows the richness of his romantic perspective by weaving his own narratives into the oral histories of his interviewees.

"The Romance of American Communism" is a rare work that unearths the past and present of "ordinary, everyday communists" amidst the vehement anti-communist literature, and is a book about individual "communists" who have been obscured in the name of system and ideology.

Furthermore, this record connects with many of today's radical social movements that question the foundation and raison d'être of 'organizations.'

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Introduction · 9

Chapter 1 Introduction · 25

Chapter 2 They came from all directions:

All Kinds of Beginnings · 67

Jewish Marxist · 73

Sarah Gordon / Ben Saltzman / Selma Gadinski

Joe Friesen / Belle Rothman / Paul Levinson

The Man Who Loved Everyone · 120

Dick Nikowski

American Populists · 130

Will Barnes / Blossom Seed / Jim Holbrook

What Communism and the Communist Party Mean · 163

Mason Goode / Arthur Chesler / Marion Moran / Diana Michaels

Chapter 3: Surviving:

From Vision to Dogma, and Back Again · 199

The Ordinariness of Everyday Life and the Impending Revolution · 204

Sarah Gordon / Selma Gadinski / Blossom Seed

The Exclusivity of the Communist World · 208

Dina Shapiro / Arthur Chesler / Norma Raymond / Eric Langetti

Party-affiliated labor union members · 229

Maggie McConnell

Ambivalence: The "Uniqueness" That Dissolves Conflict · 238

Esther Allen / Mason Goode / Lou Goodstein

On the scene · 263

Carl Millens / Maury Sachman

Underground · 283

Nettie Fossin / Hugh Armstrong / Bill Chaykin

What We Did to Each Other · 301

Sam Russell / Sophie Chesler / Tim Kelly

The Temptation of a Disciplined Revolutionary Party · 323

Larry Dougherty / Ricardo Garcia

Chapter 4 They turned in all directions:

Various Epilogues · 337

I can't imagine politics without parties. · 343

Jerome Linzer / Grace Lang / David Roth

Communist Party Members Who Turned Anti-Communist · 359

Max Bitterman

Past Wounds · 378

Arnold Richman / Bea Richman

“I’ve lost more than I’ve gained.” · 386

Maurice Silverman / Carl Peters / Dave Aveta

“Communism was part of the journey” · 400

Diane Vinson

"It was the best life a human could ever experience." · 411

Anthony Ehrenfries

Embodied Political Emotions · 425

Boris Edel

"I'll tell you what a communist is like" · 434

Eric Lanzetti

Chapter 5: Leaving · 447

Acknowledgments · 465

Recommendation / Jang Seok-jun · 467

Passing the Torch: The Unfinished History of the American Communist Party

Chapter 1 Introduction · 25

Chapter 2 They came from all directions:

All Kinds of Beginnings · 67

Jewish Marxist · 73

Sarah Gordon / Ben Saltzman / Selma Gadinski

Joe Friesen / Belle Rothman / Paul Levinson

The Man Who Loved Everyone · 120

Dick Nikowski

American Populists · 130

Will Barnes / Blossom Seed / Jim Holbrook

What Communism and the Communist Party Mean · 163

Mason Goode / Arthur Chesler / Marion Moran / Diana Michaels

Chapter 3: Surviving:

From Vision to Dogma, and Back Again · 199

The Ordinariness of Everyday Life and the Impending Revolution · 204

Sarah Gordon / Selma Gadinski / Blossom Seed

The Exclusivity of the Communist World · 208

Dina Shapiro / Arthur Chesler / Norma Raymond / Eric Langetti

Party-affiliated labor union members · 229

Maggie McConnell

Ambivalence: The "Uniqueness" That Dissolves Conflict · 238

Esther Allen / Mason Goode / Lou Goodstein

On the scene · 263

Carl Millens / Maury Sachman

Underground · 283

Nettie Fossin / Hugh Armstrong / Bill Chaykin

What We Did to Each Other · 301

Sam Russell / Sophie Chesler / Tim Kelly

The Temptation of a Disciplined Revolutionary Party · 323

Larry Dougherty / Ricardo Garcia

Chapter 4 They turned in all directions:

Various Epilogues · 337

I can't imagine politics without parties. · 343

Jerome Linzer / Grace Lang / David Roth

Communist Party Members Who Turned Anti-Communist · 359

Max Bitterman

Past Wounds · 378

Arnold Richman / Bea Richman

“I’ve lost more than I’ve gained.” · 386

Maurice Silverman / Carl Peters / Dave Aveta

“Communism was part of the journey” · 400

Diane Vinson

"It was the best life a human could ever experience." · 411

Anthony Ehrenfries

Embodied Political Emotions · 425

Boris Edel

"I'll tell you what a communist is like" · 434

Eric Lanzetti

Chapter 5: Leaving · 447

Acknowledgments · 465

Recommendation / Jang Seok-jun · 467

Passing the Torch: The Unfinished History of the American Communist Party

Into the book

“I was staggering at the speed at which ideology was hurtling towards dogma.

At that moment, my compassion for the communists was reawakened, and I felt a new respect for the ordinary, everyday communists who were crushed and overwhelmed by dogma every day.”

--- p.14~15

“I thought, ‘Oh my God, I’m going through what the Communists went through!’ And the next thought that came to me was, I have to write a book.”

--- p.15

“I realized I was a member of the working class before I realized I was Jewish or a girl.”

--- p.27

“It was during those hours spent at the kitchen table with my father and his socialist friends that we didn’t know we were poor, and that showed us an important feature of that world.”

--- p.31

“They sat at the kitchen table and felt connected to America, to Russia, to Europe, to the world.

Their people were everywhere, their power was the revolution at hand, and their empire was a 'better world.'"

--- p.34~35

“This distance detaches the act of description from the object of description (i.e. the Communists), as if the object of observation were guilty but the observer was not guilty at all.

As if they are childish and we are mature.

As if we would have known better, but they lacked the capacity to know better.

In short, the Communists were made up of weaker and inferior people, and it was as if we could not have suffered what they had suffered.”

--- p.51

“Their unique experiences, unlike those of any other American, vividly illustrate the relationship between emotional needs and historical context.

“History is in them, and they are in history.”

--- p.59

“They came in from all directions and returned in all directions.

Just as I couldn't lump together my experiences as a communist, my experiences after becoming a communist are also not lumped together.

“They became all kinds of Americans again.”

At that moment, my compassion for the communists was reawakened, and I felt a new respect for the ordinary, everyday communists who were crushed and overwhelmed by dogma every day.”

--- p.14~15

“I thought, ‘Oh my God, I’m going through what the Communists went through!’ And the next thought that came to me was, I have to write a book.”

--- p.15

“I realized I was a member of the working class before I realized I was Jewish or a girl.”

--- p.27

“It was during those hours spent at the kitchen table with my father and his socialist friends that we didn’t know we were poor, and that showed us an important feature of that world.”

--- p.31

“They sat at the kitchen table and felt connected to America, to Russia, to Europe, to the world.

Their people were everywhere, their power was the revolution at hand, and their empire was a 'better world.'"

--- p.34~35

“This distance detaches the act of description from the object of description (i.e. the Communists), as if the object of observation were guilty but the observer was not guilty at all.

As if they are childish and we are mature.

As if we would have known better, but they lacked the capacity to know better.

In short, the Communists were made up of weaker and inferior people, and it was as if we could not have suffered what they had suffered.”

--- p.51

“Their unique experiences, unlike those of any other American, vividly illustrate the relationship between emotional needs and historical context.

“History is in them, and they are in history.”

--- p.59

“They came in from all directions and returned in all directions.

Just as I couldn't lump together my experiences as a communist, my experiences after becoming a communist are also not lumped together.

“They became all kinds of Americans again.”

--- p.62

Publisher's Review

'oh my god,

'I'm going through what the communists went through!'

The next thought that came to my mind was that I should write a book.

1 million ordinary people

The inner light that captured the soul

What was inside them

It's in all of us

“I realized I was a member of the working class before I realized I was Jewish or a girl.”

One of Vivian Gornick's early works, "The Romance of American Communism," which has developed a unique style across various fields including essays, columns, criticism, and memoirs, is now available to Korean readers.

Vivian Gonick is a writer who enjoys enthusiastic support from Korean readers for her uncompromising, sharp autobiographical narratives, as well as her first-person critiques that focus on the challenges of establishing one's own perspective.

A Romance of American Communism, a record of American communists and another autobiography of the author, is a masterpiece that announced the birth of a new type of journalism and reportage literature.

This book was first published in 1977, when Vivienne Gornick was making a name for herself as a legendary journalist covering the feminist movement, and was republished in 2020 with a new foreword.

For Gonick, who has been keenly aware of his own position as a working-class Jewish immigrant throughout his life, the stigma and objectification surrounding communists was a deeply ingrained experience.

Determined to unravel this congestion in a book, he traveled across the United States, interviewing dozens of former communists.

Thus, Gonick presents to his readers “living, flesh-and-blood” communists, beings who, in the midst of miserable and miserable living conditions, displayed the most admirable passions.

His firm belief is that when we understand the vision they held, we can grasp the essence of the failures and ironies of communism.

'Romance' is a form of expression that reflects this attitude, and Gonick shows the richness of his romantic perspective by weaving his own narratives into the oral histories of his interviewees.

For the author, who was born into a leftist working-class Jewish family in the Bronx, New York, over 90 years ago and grew up and lived in a world where communists and socialists were alike, communism is as important a root and resource as feminism.

He found the impetus to write the book in a time when communism and socialism had been reduced to a kind of stigma, that is, they were regarded as outdated and alien ideologies no longer worth listening to.

In the midst of the feminist movement, suddenly confronted with the image of a communist, he decided to write a book and began to unearth the past and present of “ordinary, everyday communists” amidst the violent anti-communist literature.

In short, "The Romance of American Communism" is a book about individual "communists" who were obscured by the name of the system and ideology, and furthermore, it is a record that connects with various radical social movements today that ponder the foundation and raison d'être of "organizations."

There are so many reasons why we still need to listen to their lived experiences.

'Oh my God, I'm going through what the communists went through.'

Communism Reunited in the Wave of Feminism

As is well known, the author's identity as a radical feminist is a central part of her life and career.

Before building a full-fledged career as a writer, from 1969 to 1977, she began her life as a feminist in earnest by covering and documenting the feminist movement as a reporter for the Village Voice.

The second wave of feminism that swept through this period brought a “shock of enlightenment” that shook his whole being and the world he had lived in.

But after that, something unbelievable started happening in the women's movement.

Feminist consciousness, which was “an experience that enriched the sense of the world and existence beyond measure,” is being consumed by feminist dogma.

As 'right' and 'wrong' attitudes are quickly established and factions proliferate within major feminist organizations, any feminist who opposes the 'pro-women' line is branded an enemy.

On the day he was branded a "revisionist" for his remark at a conference in Boston that "it's not men who should be blamed, it's culture in general," memories of the American Communists, mixed with the familiar scenes of his childhood, suddenly struck him.

The intense political storm within the women's movement was enough to cast shadows of the old left, namely the American Communist Party, within him.

That memory, half-consciously recalled, vividly imprinted the dangers and horrors of a “movement that had become dogma” and led him to a deeper and more poignant insight into the history of American communism.

“I was staggering at the speed at which ideology was hurtling towards dogma.

At that moment, my compassion for the communists was reawakened, and I felt a new respect for the ordinary, everyday communists who were crushed and overwhelmed by dogma every day.”

Communism as Romance: "We" Whose Passion for the Ideal of Social Justice Blossomed

It is a well-known fact that Vivian Gornick grew up with parents who were progressive socialists and communists, but at the same time, it is a trajectory that is rarely noted or discussed.

He lived in the Bronx, a neighborhood of immigrants and the poor, until he was about twenty, and thanks to that, he became aware of “the fact that he was a member of the working class” much earlier than “that he was Jewish or a girl.”

For him, socialism and class consciousness were already “mother’s milk absorbed through flesh and bones” before he became conscious of it, and the “friends” and “we” of his family during his childhood were socialists who shared that consciousness.

Everyone who attended rallies and May Day marches, who raised money for current events or legal aid, who came to his house with the Daily Worker in tow or sat around his kitchen table, loudly discussing "issues," was one.

They all pushed, pulled, and dragged their opinions, shaping them into a single shape that fit a single question.

'Is it beneficial to the workers?'

As time passes and he ventures out into the wider world outside the Bronx, he is deeply shocked to discover that the dazzling world that filled his childhood was not the center, but a mere periphery.

In Berkeley, in the West, where I went to graduate school in English literature, even the Communists were nothing more than “nameless, faceless devils from across the ocean.”

This ignorance and hostility that Westerners showed toward the communists only served to make him a more hard-line communist.

“I became defensive and aggressive at the same time, and over time I started looking for excuses to declare myself a quintessential communist whenever and wherever I could.”

The hostile experience that had been weighing on him like a congestion began to find language through the feminist movement.

It was only after witnessing the painful spectacle of the language of feminism hardening into dogma that I finally came to understand the living meaning of communism.

He decided to write an oral history of American communists, starting with his childhood memories of the progressives who had been his constant companions.

And as the title of the book suggests, it depicts the experiences of those who were once communists as a 'romance'.

While Gonik confesses his deep affection and conviction for the narrative code he has adopted called “romance,” he also does not hesitate to reveal the “frustration” behind it.

Even Gonick is well aware that his romantic narrative has been the target of vicious attacks and condemnation from influential intellectuals on both the left and the right, particularly those who have turned to “violent anti-communism” like Theodore Draper and Hilton Kramer.

Yet, for Gonick, romance is the most appropriate way to portray “the experience of being a communist,” since many communists, in fact, have had precisely that experience of “feeling that a lifelong commitment to serious radicalism was their destiny.”

So to speak, these were cultural heroes who always lived for 'work', no different from artists, scientists, or thinkers.

On the one hand, they were extremely ordinary and everyday individuals, but the radical ideas of socialism/communism instantly elevated them to a level beyond just being alive.

The party and organized politics gave the poorest and most marginalized people “a sense of not just being alive, but of having the power to express themselves,” a sense of having reached the heart of life.

Vivian Gornick's firm belief in this book was that the lives of American Communists—those who blossomed with passion, romance, and conviction, fueled by the ideal of social justice, those whose existences were illuminated by their inner light—were worth recording, and romance remained the optimal medium for capturing that vivid experience.

He pushes forward with a sloppy, sticky, and exaggerated narrative of "the communist narrative" ("powerfully," "profoundly," "deeply," "to the very core of existence"), fleshing out the bare bones of "anti-communism."

So this book is not about 'communism', but about 'communists', not about a radical ideology that existed at a certain point in history, but about those who experienced that ideology with their whole being, those who lived through life embracing its contradictions even when the ideology degenerated into dogma.

They came from all sides: a brilliant beginning and a pure life.

“It was only during those hours spent at the kitchen table with my father and his socialist friends that we realized we were poor, and that showed us an important feature of that world.”

“They sat at the kitchen table and felt connected to America, to Russia, to Europe, to the world.

Their people were everywhere, their power was the revolution at hand, and their empire was a 'better world.'"

Vivian Gornick's maternal grandmother was a Russian Jew who escaped to the United States (Ellis Island).

His grandmother, a woman of few words, found her place in the strange world of New York and became a socialist.

At that time, many Russian Jews who had been directly involved in or ardently supported the Russian Revolution of 1905 were fleeing their homeland and settling in the United States.

Many of them quickly became socialists/communists in that new land.

When the American Communist Party emerged in 1919 through numerous socialist struggles, it was in this historical context that many of its founding members were politically trained through revolutionary experience.

As Gonick's family history illustrates, the origins of the American Communist Party are deeply connected to Jewish immigrants in New York.

The American Communist Party grew out of the experience of the Marxist revolution in Europe and the impact that revolution had on millions of Eastern European Jews.

The Jews of Russia, Poland, Hungary, etc. were the typical foreigners, and they experienced the social despair of those countries in its most oppressive form.

That despair exploded with the Russian Revolution.

“Thousands of Jews responded to the excitement and possibility that the vision of socialism brought to their lives without a way out.” Jews, with a sense of their situation as profound as their sense of exclusion, connected with Marxism during this period and experienced their formation as socialists, anarchists, Zionists, and communists.

The sense of being an excluded outsider and the hunger for creation that operated within them were strangely intertwined with the American situation.

Although the United States was an equally cold and poor country, its laws did not explicitly proclaim their subordinate status.

“In fact, American law, far from specifying limits, guaranteed these people rights.

This difference was 'America'.

It meant hope, openness, possibility, and ironically, it liberated the courage for Marxism that Europe had suppressed within many.”

Through scenes from the house and kitchen of his childhood, Gonick reconstructs the world of the American Communist Party—a wondrous world where he escaped his objective existence as an oppressed and disenfranchised worker to become a thinker, a writer, a poet—into a tangible, concrete reality.

Thanks to their presence, his kitchen ceased to be “a room in a shabby Bronx tenement and became virtually the center of his world.”

Through the Russian Revolution and Marxism, they realized “who and what they were” and acquired “a sense of rights” for the first time in their lives.

Abstract concepts with the power of transformation brought their ordinary daily lives into “a macroscopic context that changed the course of history.”

Gonnick writes that those sitting around his kitchen table in this context discovered “their historical position” and, furthermore, “their selves.”

What they truly discovered through Marxism, the Communist Party, and world socialism was nothing other than “themselves,” and they were the means of that discovery and self-creation.

“It is impossible not to love passionately the people, the atmosphere, the events, and the ideas that make one feel a surge of vitality within oneself.

In fact, it is impossible not to feel passionate emotions when such a surge occurs.

“This intense feeling was transmitted to those around me during my childhood through Marxism as interpreted by the Communist Party.”

They scattered in all directions: a merciless romance

“They came in from all directions and returned in all directions.

Just as I couldn't lump together my experiences as a communist, my experiences after becoming a communist are also not lumped together.

“They became all kinds of Americans again.”

The Communist Party of the United States, formed two years after the Russian Revolution, grew steadily over the next 40 years.

The number of party members, which was 2,000 to 3,000 at the start, increased to 75,000 in the 1930s and 1940s when its influence was at its peak, and if you add up the number of communist party members who once maintained their party membership, it would amount to about 1 million.

While many were working-class people struggling to survive—immigrant Jews, West Virginia miners, and California fruit pickers—there were also many educated middle-class people (teachers, scientists, writers).

Many people who had “dwelt on the vague antipathy to social injustice during the Great Depression and World War II” came from all over the world.

Most rank-and-file party members had never set foot in party headquarters or been involved in internal policy-making meetings, but they knew exactly what was happening.

The fact that union members belonging to the party played a decisive role in the emergence of industrial workers in the United States.

The fact that party lawyers defended black people in the deep south of the United States, where racism is rampant.

And that “the party’s organizers lived, worked, and sometimes died alongside miners in Appalachia, farm workers in California, and steelworkers in Pittsburgh.”

The Communist Party of America as an organization and its individual members were closely linked through these events that marked the turning points of American history.

“The Marxist vision of world solidarity, translated through the Communist Party, gave the ordinary Zhang San directors a sense of humanity and a sense that life was grand and clear.”

Gonick mercilessly points out that this passion soon becomes the seed of self-deception and tragedy.

The Communist Party's overbearing sense of self soon prevented its members from facing the corruption of the Soviet police state.

The American Communist Party "made a fuss from time to time about meeting the demands of the world's only socialist state at all costs," and was able to continue to deceive itself even during the 1930s and 1940s, as the Soviet Union's totalitarian tendencies grew stronger and its true nature was concealed.

By the 1950s, amidst the fervor of McCarthyism, countless Communists were imprisoned, and to escape even worse situations, they declared themselves “missing” or went “underground.”

But it was an internal scandal that shook the world in 1956 that tore the party apart.

In February of that year, Nikita Khrushchev exposed the horrors of Stalin's rule in his speech at the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.

The speech brought political devastation not only to the Communist Party of America but to leftist organizations around the world, with 30,000 people leaving the party within weeks of its release.

What only those who have lost and been broken can understand: the truth of contradiction.

“Their unique experiences, unlike those of any other American, vividly illustrate the relationship between emotional needs and historical context.

“History is in them, and they are in history.”

Gonik captures the irony of the Communist experience by recalling the series of events that had deeply shocked and traumatized him even when he was twenty, and especially Khrushchev's revelations in 1956.

The things Khrushchev exposed were well known to many, but they were also things that had been “pushed to the back of our consciousness for a very long time.”

“The Khrushchev report tore the last thread from the fabric of trust that was already on the verge of disintegration.

“For the past three or four years, I have been in a state of constant awe as the weight of these overly simplistic socialist explanations has been weighing down my growing inner life.”

But one thing is clear: this irony is also one aspect of the passionate dream once cherished by Communists.

“Nothing has inspired such a passionate and shared dream among the people of the world as communism.

(......) It was this dream that made communism such a metaphorical experience, that made people like my aunt fall from vision to dogma, from ecstasy to misery.”

This, in Gonick's view, is a point overlooked by countless writings on communism or the experience of being a communist.

In other words, most works on communists erase the complexity of the lives they lived through by treating these dreams and passions as eccentric and bizarre things that exist only in a bygone erasure.

In particular, the omnipotent word “Stalinism” “pretends not to know the contradictory life that sways behind the word” and “denies that experience is the source of the complex human being.”

This kind of oppressive distance provokes a strong rejection in him, because it is one way of constructing “otherness” under the guise of objectivity.

“This distance detaches the act of description from the object of description (i.e. the Communists), as if the object of observation were guilty but the observer was not guilty at all.

As if they are childish and we are mature.

As if we would have known better, but they lacked the capacity to know better.

(......) In short, the Communists were made up of weaker and inferior people, and it was as if we could not experience what they experienced.”

What is erased in this distance is a corner of American life that they represented and that was within them.

What kind of America do the communists' unique experiences of enduring social isolation, economic and professional deprivation, and ultimately imprisonment reveal? What kind of America were they rooted in, and what kind of America did they once create? What specific conditions of American life spoke to their hunger? These are the questions that anti-communism and the Cold War framework fail to capture.

In the end, ‘romance’ is not just a rhetoric.

It is Gonick's own attitude and method of resisting this tone that creates a smokescreen between the experiences of communists and readers.

To “understand from a human perspective” the “countless people who have walked a tightrope their entire lives between living as communists without compromising their ideals and living as communist party members who cannot ignore the safety of the organization.”

And to give exclusive place to “the unique claims contained in individual human experience.”

In doing so, we can respect the historical trajectory drawn by the communists while avoiding the same pitfalls and contradictions they fell into.

'I'm going through what the communists went through!'

The next thought that came to my mind was that I should write a book.

1 million ordinary people

The inner light that captured the soul

What was inside them

It's in all of us

“I realized I was a member of the working class before I realized I was Jewish or a girl.”

One of Vivian Gornick's early works, "The Romance of American Communism," which has developed a unique style across various fields including essays, columns, criticism, and memoirs, is now available to Korean readers.

Vivian Gonick is a writer who enjoys enthusiastic support from Korean readers for her uncompromising, sharp autobiographical narratives, as well as her first-person critiques that focus on the challenges of establishing one's own perspective.

A Romance of American Communism, a record of American communists and another autobiography of the author, is a masterpiece that announced the birth of a new type of journalism and reportage literature.

This book was first published in 1977, when Vivienne Gornick was making a name for herself as a legendary journalist covering the feminist movement, and was republished in 2020 with a new foreword.

For Gonick, who has been keenly aware of his own position as a working-class Jewish immigrant throughout his life, the stigma and objectification surrounding communists was a deeply ingrained experience.

Determined to unravel this congestion in a book, he traveled across the United States, interviewing dozens of former communists.

Thus, Gonick presents to his readers “living, flesh-and-blood” communists, beings who, in the midst of miserable and miserable living conditions, displayed the most admirable passions.

His firm belief is that when we understand the vision they held, we can grasp the essence of the failures and ironies of communism.

'Romance' is a form of expression that reflects this attitude, and Gonick shows the richness of his romantic perspective by weaving his own narratives into the oral histories of his interviewees.

For the author, who was born into a leftist working-class Jewish family in the Bronx, New York, over 90 years ago and grew up and lived in a world where communists and socialists were alike, communism is as important a root and resource as feminism.

He found the impetus to write the book in a time when communism and socialism had been reduced to a kind of stigma, that is, they were regarded as outdated and alien ideologies no longer worth listening to.

In the midst of the feminist movement, suddenly confronted with the image of a communist, he decided to write a book and began to unearth the past and present of “ordinary, everyday communists” amidst the violent anti-communist literature.

In short, "The Romance of American Communism" is a book about individual "communists" who were obscured by the name of the system and ideology, and furthermore, it is a record that connects with various radical social movements today that ponder the foundation and raison d'être of "organizations."

There are so many reasons why we still need to listen to their lived experiences.

'Oh my God, I'm going through what the communists went through.'

Communism Reunited in the Wave of Feminism

As is well known, the author's identity as a radical feminist is a central part of her life and career.

Before building a full-fledged career as a writer, from 1969 to 1977, she began her life as a feminist in earnest by covering and documenting the feminist movement as a reporter for the Village Voice.

The second wave of feminism that swept through this period brought a “shock of enlightenment” that shook his whole being and the world he had lived in.

But after that, something unbelievable started happening in the women's movement.

Feminist consciousness, which was “an experience that enriched the sense of the world and existence beyond measure,” is being consumed by feminist dogma.

As 'right' and 'wrong' attitudes are quickly established and factions proliferate within major feminist organizations, any feminist who opposes the 'pro-women' line is branded an enemy.

On the day he was branded a "revisionist" for his remark at a conference in Boston that "it's not men who should be blamed, it's culture in general," memories of the American Communists, mixed with the familiar scenes of his childhood, suddenly struck him.

The intense political storm within the women's movement was enough to cast shadows of the old left, namely the American Communist Party, within him.

That memory, half-consciously recalled, vividly imprinted the dangers and horrors of a “movement that had become dogma” and led him to a deeper and more poignant insight into the history of American communism.

“I was staggering at the speed at which ideology was hurtling towards dogma.

At that moment, my compassion for the communists was reawakened, and I felt a new respect for the ordinary, everyday communists who were crushed and overwhelmed by dogma every day.”

Communism as Romance: "We" Whose Passion for the Ideal of Social Justice Blossomed

It is a well-known fact that Vivian Gornick grew up with parents who were progressive socialists and communists, but at the same time, it is a trajectory that is rarely noted or discussed.

He lived in the Bronx, a neighborhood of immigrants and the poor, until he was about twenty, and thanks to that, he became aware of “the fact that he was a member of the working class” much earlier than “that he was Jewish or a girl.”

For him, socialism and class consciousness were already “mother’s milk absorbed through flesh and bones” before he became conscious of it, and the “friends” and “we” of his family during his childhood were socialists who shared that consciousness.

Everyone who attended rallies and May Day marches, who raised money for current events or legal aid, who came to his house with the Daily Worker in tow or sat around his kitchen table, loudly discussing "issues," was one.

They all pushed, pulled, and dragged their opinions, shaping them into a single shape that fit a single question.

'Is it beneficial to the workers?'

As time passes and he ventures out into the wider world outside the Bronx, he is deeply shocked to discover that the dazzling world that filled his childhood was not the center, but a mere periphery.

In Berkeley, in the West, where I went to graduate school in English literature, even the Communists were nothing more than “nameless, faceless devils from across the ocean.”

This ignorance and hostility that Westerners showed toward the communists only served to make him a more hard-line communist.

“I became defensive and aggressive at the same time, and over time I started looking for excuses to declare myself a quintessential communist whenever and wherever I could.”

The hostile experience that had been weighing on him like a congestion began to find language through the feminist movement.

It was only after witnessing the painful spectacle of the language of feminism hardening into dogma that I finally came to understand the living meaning of communism.

He decided to write an oral history of American communists, starting with his childhood memories of the progressives who had been his constant companions.

And as the title of the book suggests, it depicts the experiences of those who were once communists as a 'romance'.

While Gonik confesses his deep affection and conviction for the narrative code he has adopted called “romance,” he also does not hesitate to reveal the “frustration” behind it.

Even Gonick is well aware that his romantic narrative has been the target of vicious attacks and condemnation from influential intellectuals on both the left and the right, particularly those who have turned to “violent anti-communism” like Theodore Draper and Hilton Kramer.

Yet, for Gonick, romance is the most appropriate way to portray “the experience of being a communist,” since many communists, in fact, have had precisely that experience of “feeling that a lifelong commitment to serious radicalism was their destiny.”

So to speak, these were cultural heroes who always lived for 'work', no different from artists, scientists, or thinkers.

On the one hand, they were extremely ordinary and everyday individuals, but the radical ideas of socialism/communism instantly elevated them to a level beyond just being alive.

The party and organized politics gave the poorest and most marginalized people “a sense of not just being alive, but of having the power to express themselves,” a sense of having reached the heart of life.

Vivian Gornick's firm belief in this book was that the lives of American Communists—those who blossomed with passion, romance, and conviction, fueled by the ideal of social justice, those whose existences were illuminated by their inner light—were worth recording, and romance remained the optimal medium for capturing that vivid experience.

He pushes forward with a sloppy, sticky, and exaggerated narrative of "the communist narrative" ("powerfully," "profoundly," "deeply," "to the very core of existence"), fleshing out the bare bones of "anti-communism."

So this book is not about 'communism', but about 'communists', not about a radical ideology that existed at a certain point in history, but about those who experienced that ideology with their whole being, those who lived through life embracing its contradictions even when the ideology degenerated into dogma.

They came from all sides: a brilliant beginning and a pure life.

“It was only during those hours spent at the kitchen table with my father and his socialist friends that we realized we were poor, and that showed us an important feature of that world.”

“They sat at the kitchen table and felt connected to America, to Russia, to Europe, to the world.

Their people were everywhere, their power was the revolution at hand, and their empire was a 'better world.'"

Vivian Gornick's maternal grandmother was a Russian Jew who escaped to the United States (Ellis Island).

His grandmother, a woman of few words, found her place in the strange world of New York and became a socialist.

At that time, many Russian Jews who had been directly involved in or ardently supported the Russian Revolution of 1905 were fleeing their homeland and settling in the United States.

Many of them quickly became socialists/communists in that new land.

When the American Communist Party emerged in 1919 through numerous socialist struggles, it was in this historical context that many of its founding members were politically trained through revolutionary experience.

As Gonick's family history illustrates, the origins of the American Communist Party are deeply connected to Jewish immigrants in New York.

The American Communist Party grew out of the experience of the Marxist revolution in Europe and the impact that revolution had on millions of Eastern European Jews.

The Jews of Russia, Poland, Hungary, etc. were the typical foreigners, and they experienced the social despair of those countries in its most oppressive form.

That despair exploded with the Russian Revolution.

“Thousands of Jews responded to the excitement and possibility that the vision of socialism brought to their lives without a way out.” Jews, with a sense of their situation as profound as their sense of exclusion, connected with Marxism during this period and experienced their formation as socialists, anarchists, Zionists, and communists.

The sense of being an excluded outsider and the hunger for creation that operated within them were strangely intertwined with the American situation.

Although the United States was an equally cold and poor country, its laws did not explicitly proclaim their subordinate status.

“In fact, American law, far from specifying limits, guaranteed these people rights.

This difference was 'America'.

It meant hope, openness, possibility, and ironically, it liberated the courage for Marxism that Europe had suppressed within many.”

Through scenes from the house and kitchen of his childhood, Gonick reconstructs the world of the American Communist Party—a wondrous world where he escaped his objective existence as an oppressed and disenfranchised worker to become a thinker, a writer, a poet—into a tangible, concrete reality.

Thanks to their presence, his kitchen ceased to be “a room in a shabby Bronx tenement and became virtually the center of his world.”

Through the Russian Revolution and Marxism, they realized “who and what they were” and acquired “a sense of rights” for the first time in their lives.

Abstract concepts with the power of transformation brought their ordinary daily lives into “a macroscopic context that changed the course of history.”

Gonnick writes that those sitting around his kitchen table in this context discovered “their historical position” and, furthermore, “their selves.”

What they truly discovered through Marxism, the Communist Party, and world socialism was nothing other than “themselves,” and they were the means of that discovery and self-creation.

“It is impossible not to love passionately the people, the atmosphere, the events, and the ideas that make one feel a surge of vitality within oneself.

In fact, it is impossible not to feel passionate emotions when such a surge occurs.

“This intense feeling was transmitted to those around me during my childhood through Marxism as interpreted by the Communist Party.”

They scattered in all directions: a merciless romance

“They came in from all directions and returned in all directions.

Just as I couldn't lump together my experiences as a communist, my experiences after becoming a communist are also not lumped together.

“They became all kinds of Americans again.”

The Communist Party of the United States, formed two years after the Russian Revolution, grew steadily over the next 40 years.

The number of party members, which was 2,000 to 3,000 at the start, increased to 75,000 in the 1930s and 1940s when its influence was at its peak, and if you add up the number of communist party members who once maintained their party membership, it would amount to about 1 million.

While many were working-class people struggling to survive—immigrant Jews, West Virginia miners, and California fruit pickers—there were also many educated middle-class people (teachers, scientists, writers).

Many people who had “dwelt on the vague antipathy to social injustice during the Great Depression and World War II” came from all over the world.

Most rank-and-file party members had never set foot in party headquarters or been involved in internal policy-making meetings, but they knew exactly what was happening.

The fact that union members belonging to the party played a decisive role in the emergence of industrial workers in the United States.

The fact that party lawyers defended black people in the deep south of the United States, where racism is rampant.

And that “the party’s organizers lived, worked, and sometimes died alongside miners in Appalachia, farm workers in California, and steelworkers in Pittsburgh.”

The Communist Party of America as an organization and its individual members were closely linked through these events that marked the turning points of American history.

“The Marxist vision of world solidarity, translated through the Communist Party, gave the ordinary Zhang San directors a sense of humanity and a sense that life was grand and clear.”

Gonick mercilessly points out that this passion soon becomes the seed of self-deception and tragedy.

The Communist Party's overbearing sense of self soon prevented its members from facing the corruption of the Soviet police state.

The American Communist Party "made a fuss from time to time about meeting the demands of the world's only socialist state at all costs," and was able to continue to deceive itself even during the 1930s and 1940s, as the Soviet Union's totalitarian tendencies grew stronger and its true nature was concealed.

By the 1950s, amidst the fervor of McCarthyism, countless Communists were imprisoned, and to escape even worse situations, they declared themselves “missing” or went “underground.”

But it was an internal scandal that shook the world in 1956 that tore the party apart.

In February of that year, Nikita Khrushchev exposed the horrors of Stalin's rule in his speech at the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.

The speech brought political devastation not only to the Communist Party of America but to leftist organizations around the world, with 30,000 people leaving the party within weeks of its release.

What only those who have lost and been broken can understand: the truth of contradiction.

“Their unique experiences, unlike those of any other American, vividly illustrate the relationship between emotional needs and historical context.

“History is in them, and they are in history.”

Gonik captures the irony of the Communist experience by recalling the series of events that had deeply shocked and traumatized him even when he was twenty, and especially Khrushchev's revelations in 1956.

The things Khrushchev exposed were well known to many, but they were also things that had been “pushed to the back of our consciousness for a very long time.”

“The Khrushchev report tore the last thread from the fabric of trust that was already on the verge of disintegration.

“For the past three or four years, I have been in a state of constant awe as the weight of these overly simplistic socialist explanations has been weighing down my growing inner life.”

But one thing is clear: this irony is also one aspect of the passionate dream once cherished by Communists.

“Nothing has inspired such a passionate and shared dream among the people of the world as communism.

(......) It was this dream that made communism such a metaphorical experience, that made people like my aunt fall from vision to dogma, from ecstasy to misery.”

This, in Gonick's view, is a point overlooked by countless writings on communism or the experience of being a communist.

In other words, most works on communists erase the complexity of the lives they lived through by treating these dreams and passions as eccentric and bizarre things that exist only in a bygone erasure.

In particular, the omnipotent word “Stalinism” “pretends not to know the contradictory life that sways behind the word” and “denies that experience is the source of the complex human being.”

This kind of oppressive distance provokes a strong rejection in him, because it is one way of constructing “otherness” under the guise of objectivity.

“This distance detaches the act of description from the object of description (i.e. the Communists), as if the object of observation were guilty but the observer was not guilty at all.

As if they are childish and we are mature.

As if we would have known better, but they lacked the capacity to know better.

(......) In short, the Communists were made up of weaker and inferior people, and it was as if we could not experience what they experienced.”

What is erased in this distance is a corner of American life that they represented and that was within them.

What kind of America do the communists' unique experiences of enduring social isolation, economic and professional deprivation, and ultimately imprisonment reveal? What kind of America were they rooted in, and what kind of America did they once create? What specific conditions of American life spoke to their hunger? These are the questions that anti-communism and the Cold War framework fail to capture.

In the end, ‘romance’ is not just a rhetoric.

It is Gonick's own attitude and method of resisting this tone that creates a smokescreen between the experiences of communists and readers.

To “understand from a human perspective” the “countless people who have walked a tightrope their entire lives between living as communists without compromising their ideals and living as communist party members who cannot ignore the safety of the organization.”

And to give exclusive place to “the unique claims contained in individual human experience.”

In doing so, we can respect the historical trajectory drawn by the communists while avoiding the same pitfalls and contradictions they fell into.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: November 11, 2024

- Page count, weight, size: 480 pages | 135*205*30mm

- ISBN13: 9791168731318

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)