Bury me at Wounded Knee

|

Description

Book Introduction

Bestseller in the History category on Amazon in the United States

The world's most widely read masterpiece of Indian literature

“If Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring sparked the modern environmental movement,

This book brought to public attention the depredations of the United States against Native Americans.”

Hampton Size (novelist)

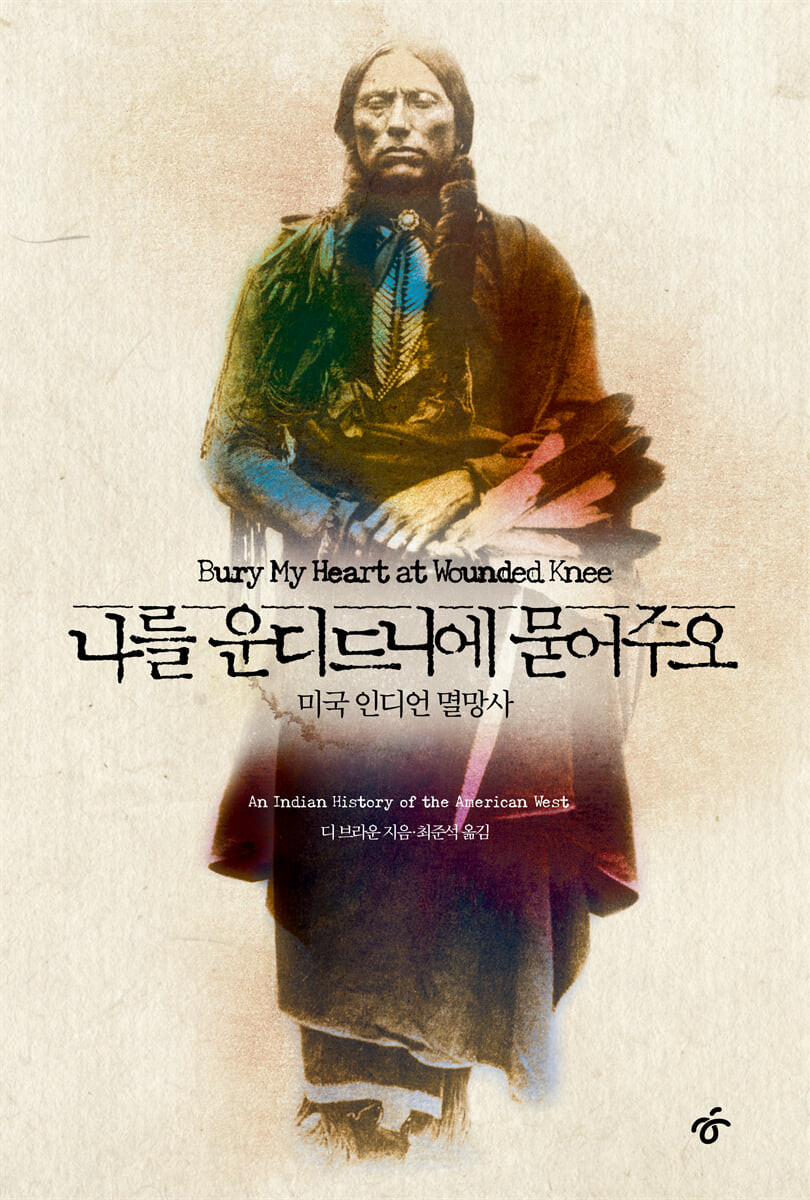

Bury Me at Wounded Knee, a masterpiece of Indian literature that has been translated into over 10 languages and sold over 5 million copies worldwide since its publication in the United States in 1970, has been republished.

In Korea, it was first translated and introduced in 1996, and has been republished repeatedly by four publishers, garnering much anticipation and support from readers.

The recent expiration of the domestic copyright contract has caused great disappointment among existing and potential readers, and there have been many earnest requests for the publication to be resumed soon.

Accordingly, Hankyoreh Publishing changed the existing cover and revised the incorrect editing of the text to republish it.

From the 1860s to the 1890s, the American West was a time of gold, wagons, and gunslingers.

The Indians had no concept of land ownership, and any white man who came onto their land had to take it for gold.

“God has truly blessed us.

The words of an American major, “Gold is here at our feet, we just have to pick it up,” represent the beliefs of white people at the time.

To seize land, Washington policymakers coined the term "manifest destiny."

'Manifest Destiny' meant that Europeans and their descendants were destined to rule the New World and, as the ruling people, were naturally responsible for all the Indian lands, forests, and mines.

The Indians signed the transfer papers in the white man's style 'to please the white man.'

All the white people gave in exchange for the land was a few beads, which the Indians found fascinating.

For the next 30 years, the white people continued to take over the land with lies until the Indians were wiped out, and the Indians who consistently believed the white people's words were eventually exterminated.

Bury Me at Wounded Knee is a documentary about the countless struggles of true pacifist and conservationist Indian warriors such as Manuelito, Red Cloud, Black Kettle, Sitting Ox, Hawk Nose, Little Raven, Joseph, and Geronimo to save their tribes from the Indian massacre wars caused by the endless greed of white people.

“No white man, regardless of who he is, may settle or occupy any part of this territory.

There is also a vivid account of the countless treaties that were broken and not kept, such as the Treaty of 1868, which stated that “no one may pass through this territory without the consent of the Indians.”

It is particularly significant in that it looks back on the era of Western expansion from the perspective of the Indians, making the most of their language and oral traditions.

The world's most widely read masterpiece of Indian literature

“If Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring sparked the modern environmental movement,

This book brought to public attention the depredations of the United States against Native Americans.”

Hampton Size (novelist)

Bury Me at Wounded Knee, a masterpiece of Indian literature that has been translated into over 10 languages and sold over 5 million copies worldwide since its publication in the United States in 1970, has been republished.

In Korea, it was first translated and introduced in 1996, and has been republished repeatedly by four publishers, garnering much anticipation and support from readers.

The recent expiration of the domestic copyright contract has caused great disappointment among existing and potential readers, and there have been many earnest requests for the publication to be resumed soon.

Accordingly, Hankyoreh Publishing changed the existing cover and revised the incorrect editing of the text to republish it.

From the 1860s to the 1890s, the American West was a time of gold, wagons, and gunslingers.

The Indians had no concept of land ownership, and any white man who came onto their land had to take it for gold.

“God has truly blessed us.

The words of an American major, “Gold is here at our feet, we just have to pick it up,” represent the beliefs of white people at the time.

To seize land, Washington policymakers coined the term "manifest destiny."

'Manifest Destiny' meant that Europeans and their descendants were destined to rule the New World and, as the ruling people, were naturally responsible for all the Indian lands, forests, and mines.

The Indians signed the transfer papers in the white man's style 'to please the white man.'

All the white people gave in exchange for the land was a few beads, which the Indians found fascinating.

For the next 30 years, the white people continued to take over the land with lies until the Indians were wiped out, and the Indians who consistently believed the white people's words were eventually exterminated.

Bury Me at Wounded Knee is a documentary about the countless struggles of true pacifist and conservationist Indian warriors such as Manuelito, Red Cloud, Black Kettle, Sitting Ox, Hawk Nose, Little Raven, Joseph, and Geronimo to save their tribes from the Indian massacre wars caused by the endless greed of white people.

“No white man, regardless of who he is, may settle or occupy any part of this territory.

There is also a vivid account of the countless treaties that were broken and not kept, such as the Treaty of 1868, which stated that “no one may pass through this territory without the consent of the Indians.”

It is particularly significant in that it looks back on the era of Western expansion from the perspective of the Indians, making the most of their language and oral traditions.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Preface to the Revised Edition

Preface to the first edition

1.

Their attitude is polite and excellent.

2.

The Long March of the Navajo

3.

Little Crow War

4.

Cheyenne! The fight is imminent.

5.

Powder River Invasion

6.

Red Cloud, Victory

7.

A good Indian is a dead Indian

8.

My uncle, Donehogawa

9.

Coaches and Apache Guerrillas

10.

Captain Jack's Trials

11.

Bison Rescue War

12.

Black Hill Shooter Battle

13.

The escape of the Nez Perce people

14.

The Exodus of the Cheyenne

15.

Sun Bear Becomes Human

16.

Youths go too!

17.

The Last of the Apache Chief

18.

Dance of the Ghosts

19.

Wounded Knee

Translator's Note

Preface to the first edition

1.

Their attitude is polite and excellent.

2.

The Long March of the Navajo

3.

Little Crow War

4.

Cheyenne! The fight is imminent.

5.

Powder River Invasion

6.

Red Cloud, Victory

7.

A good Indian is a dead Indian

8.

My uncle, Donehogawa

9.

Coaches and Apache Guerrillas

10.

Captain Jack's Trials

11.

Bison Rescue War

12.

Black Hill Shooter Battle

13.

The escape of the Nez Perce people

14.

The Exodus of the Cheyenne

15.

Sun Bear Becomes Human

16.

Youths go too!

17.

The Last of the Apache Chief

18.

Dance of the Ghosts

19.

Wounded Knee

Translator's Note

Into the book

The history of tragedy begins with Christopher Columbus, who gave the name Indian to the people of the New World.

White Europeans pronounced the name slightly differently: Indienne, Indiana, Indian, etc.

Hong In-jong is a name given later.

The Taino people of San Salvador Island, as was their custom when entertaining guests, treated Columbus and his men with gifts and courtesy.

Columbus sent the following letter to the King of Spain:

“They are so peaceful and docile, I swear to Your Majesty, that there is no better people in the world.

They love their neighbors as themselves, their words are gentle and kind, and they always have a smile on their face.

Although they are naked, their attitude is polite and admirable.”

--- p.17

In the decade before the Civil War, more than 150,000 white settlers breached the left flank of the "Permanent Indian Line" and poured into Santee lands.

Because of two deceptive treaties, the Forest Sioux were forced to cede more than 90 percent of their land and live in a narrow strip of land along the Minnesota River.

The station officials and merchants swarmed around the Santee like vultures around the carcass of a slaughtered buffalo, swindling them out of the pensions they had been receiving for giving up their land.

The big eagle said.

“Many white people hurled abuse at the Indians and treated them roughly.

There may be excuses, but the Indians thought differently.

When white people saw Indians, they showed an attitude of 'I am better than you.'

The Indians did not like this attitude.

There must have been a reason, but the Dakota Sioux did not think there was anyone better than them.

Some white men hurled abuse at the Indian women and humiliated them.

Such behavior is clearly inexcusable.

Because of that, many Indians came to hate white people.”

--- p.67~68

The cavalry were driving away a stray horse and mule, but Sivington's men opened fire before they could even hear where they had caught the animals.

After this engagement, Sivington sent more troops to raid a Cheyenne village near Cedar Bluffs, killing two women and two children.

The artillerymen who attacked Black Kettle Village on May 16th were also members of Sivington's unit in Denver, who had no authority to operate in Kansas.

Commander George S.

Lieutenant Eayre had been ordered by Colonel Sivington to “kill every Cheyenne you see, wherever and whenever you see them.”

William Bent and the Black Kettle agreed that if such incidents continued, an all-out war would break out across the plains.

“It is neither my intention nor my desire to wage war against white people.

I want to live in peace and harmony with my people, and I want them to live that way too.

You can't fight white people.

“I want to live in peace,” the black kettle confessed.

--- p.112

As the battle drew to a close, the encirclement between the Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Sioux on the other side became so tight that the Indians were even wounding each other from a hail of arrows.

But that was the end of it all.

Not a single American soldier survived.

As a dog emerged from among the dead, a Sioux warrior approached to catch it.

Then the Cheyenne warrior Big Rascal shouted, “Don’t let him go!” and someone immediately shot him dead with an arrow.

This is the battle that white people call the 'Petterman Massacre'.

The Indians call this fight "the battle of the hundred dead."

The losses were also severe on the Indian side.

Nearly 200 people were killed or injured.

Because the cold was so severe, the Indians evacuated the wounded to a temporary camp to prevent them from freezing.

The next day, we were stranded in a deafening blizzard, but the weather cleared up and we returned to the village on the Gaejatong River.

--- p.191~192

Yellow Bear of the Arapaho also agreed to bring his tribe to Fort Cobb.

A few days later, a Comanche chief named Tosawi led his tribe in surrender.

Tosawi came before Sheridan, his eyes shining, and he said his name, adding two more words in broken English.

“Tossawi, good Indian.”

It was at this time that General Sheridan uttered those immortal words that are still on people's lips today.

“All the good Indians I’ve ever seen are dead.”

This phrase was picked up by Lieutenant Charles Nordstrom, who was present, and became a catchphrase among the American people.

“The only good Indian is a dead Indian.”

--- p.237~238

By the spring of 1875, most Apache were trapped in Indian country or had fled to Mexico.

In March, General Crook moved to Arizona to command Platt.

The Cheyenne and Sioux, who had endured life in the Indian homelands longer than the Apache, were showing signs of rebellion.

A forced peace settled over the deserts, peaks, and hills of Apache territory.

Ironically, this peace was maintained by the persistent efforts of two white men who won the Apaches' trust by accepting them as human beings rather than bloodthirsty savages.

Tom Jeffords, an agnostic, and John Klum of the Dutch Reformed Church were optimists, but they were not foolish enough to expect too much.

Even in the eyes of the white Southwesterners who protected the Apache's rights, the future looked extremely uncertain.

--- p.299~300

The Kiowa people said that the magician had brought about his own death by using magic to take the lives of his own people.

Three years later, Satanta, who was wasting away in the prison infirmary, found freedom by throwing himself from a high window and dying.

That same year, Lone Wolf, suffering from malaria, was allowed to return to Fort Sil, but died less than a year later.

The great chiefs are gone.

The mighty Kiowa and Comanche tribes were eroded, and the buffalo they had been trying to save disappeared.

All this happened in less than ten years.

--- p.369

Mad Horse died that night, September 5, 1877, at the age of thirty-five.

The next morning, the US military handed the chief's body over to his parents.

They placed their son's body in a wooden box, tied it to a horse-drawn travois, and carried it to the Spotted Tail Police Station, where it was placed on a dais.

The ancestors who mourned his death did not leave the place until the month of dry grass had passed.

Then, in the month when leaves were falling, heartbreaking news arrived.

“The Sioux must leave Nebraska and migrate to a new homeland on the Missouri River.”

On a dry, crisp autumn day in 1877, the Indians, under the watchful eye of the American army, embarked on a journey of exile to the barren wastes of the northeast, where not a blade of grass grew.

Along the way, some tribes broke away from the procession and turned northwest.

They planned to flee to Canada and join the Satso.

Among those who fled were the parents of Mad Horse, who had kept their son's heart and remains.

They buried their child's bones somewhere near a small creek they called Wounded Knee, a place only they knew, called Changkpe Opi Wakpala in the Sioux language.

--- p.419~420

The widows, orphans, and remaining warriors held captive at Fort Robinson were moved to Red Cloud Station on Pine Ridge, where they were joined by blunt swords, after months of delay due to the delays of Washington bureaucracy.

After waiting for several more months, the Cheyenne at Fort Kio were given a residence on the Tongue River, and the Dull Knife party, now reduced to a few men at Pine Ridge, was finally allowed to stay with the tribe.

But it was too late.

After all power was taken from the Cheyenne.

Since the Sand Creek Massacre, fate has dealt a devastating blow to this beautiful tribe.

The seeds of the tribe were scattered with the wind.

Before leaving the south, a warrior said:

“We will go north, risking everything.

Even if we die fighting, our names will remain deep in the hearts of our people.”

But soon there will be no one to remember them or call their names.

Now that beautiful tribe is gone.

White Europeans pronounced the name slightly differently: Indienne, Indiana, Indian, etc.

Hong In-jong is a name given later.

The Taino people of San Salvador Island, as was their custom when entertaining guests, treated Columbus and his men with gifts and courtesy.

Columbus sent the following letter to the King of Spain:

“They are so peaceful and docile, I swear to Your Majesty, that there is no better people in the world.

They love their neighbors as themselves, their words are gentle and kind, and they always have a smile on their face.

Although they are naked, their attitude is polite and admirable.”

--- p.17

In the decade before the Civil War, more than 150,000 white settlers breached the left flank of the "Permanent Indian Line" and poured into Santee lands.

Because of two deceptive treaties, the Forest Sioux were forced to cede more than 90 percent of their land and live in a narrow strip of land along the Minnesota River.

The station officials and merchants swarmed around the Santee like vultures around the carcass of a slaughtered buffalo, swindling them out of the pensions they had been receiving for giving up their land.

The big eagle said.

“Many white people hurled abuse at the Indians and treated them roughly.

There may be excuses, but the Indians thought differently.

When white people saw Indians, they showed an attitude of 'I am better than you.'

The Indians did not like this attitude.

There must have been a reason, but the Dakota Sioux did not think there was anyone better than them.

Some white men hurled abuse at the Indian women and humiliated them.

Such behavior is clearly inexcusable.

Because of that, many Indians came to hate white people.”

--- p.67~68

The cavalry were driving away a stray horse and mule, but Sivington's men opened fire before they could even hear where they had caught the animals.

After this engagement, Sivington sent more troops to raid a Cheyenne village near Cedar Bluffs, killing two women and two children.

The artillerymen who attacked Black Kettle Village on May 16th were also members of Sivington's unit in Denver, who had no authority to operate in Kansas.

Commander George S.

Lieutenant Eayre had been ordered by Colonel Sivington to “kill every Cheyenne you see, wherever and whenever you see them.”

William Bent and the Black Kettle agreed that if such incidents continued, an all-out war would break out across the plains.

“It is neither my intention nor my desire to wage war against white people.

I want to live in peace and harmony with my people, and I want them to live that way too.

You can't fight white people.

“I want to live in peace,” the black kettle confessed.

--- p.112

As the battle drew to a close, the encirclement between the Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Sioux on the other side became so tight that the Indians were even wounding each other from a hail of arrows.

But that was the end of it all.

Not a single American soldier survived.

As a dog emerged from among the dead, a Sioux warrior approached to catch it.

Then the Cheyenne warrior Big Rascal shouted, “Don’t let him go!” and someone immediately shot him dead with an arrow.

This is the battle that white people call the 'Petterman Massacre'.

The Indians call this fight "the battle of the hundred dead."

The losses were also severe on the Indian side.

Nearly 200 people were killed or injured.

Because the cold was so severe, the Indians evacuated the wounded to a temporary camp to prevent them from freezing.

The next day, we were stranded in a deafening blizzard, but the weather cleared up and we returned to the village on the Gaejatong River.

--- p.191~192

Yellow Bear of the Arapaho also agreed to bring his tribe to Fort Cobb.

A few days later, a Comanche chief named Tosawi led his tribe in surrender.

Tosawi came before Sheridan, his eyes shining, and he said his name, adding two more words in broken English.

“Tossawi, good Indian.”

It was at this time that General Sheridan uttered those immortal words that are still on people's lips today.

“All the good Indians I’ve ever seen are dead.”

This phrase was picked up by Lieutenant Charles Nordstrom, who was present, and became a catchphrase among the American people.

“The only good Indian is a dead Indian.”

--- p.237~238

By the spring of 1875, most Apache were trapped in Indian country or had fled to Mexico.

In March, General Crook moved to Arizona to command Platt.

The Cheyenne and Sioux, who had endured life in the Indian homelands longer than the Apache, were showing signs of rebellion.

A forced peace settled over the deserts, peaks, and hills of Apache territory.

Ironically, this peace was maintained by the persistent efforts of two white men who won the Apaches' trust by accepting them as human beings rather than bloodthirsty savages.

Tom Jeffords, an agnostic, and John Klum of the Dutch Reformed Church were optimists, but they were not foolish enough to expect too much.

Even in the eyes of the white Southwesterners who protected the Apache's rights, the future looked extremely uncertain.

--- p.299~300

The Kiowa people said that the magician had brought about his own death by using magic to take the lives of his own people.

Three years later, Satanta, who was wasting away in the prison infirmary, found freedom by throwing himself from a high window and dying.

That same year, Lone Wolf, suffering from malaria, was allowed to return to Fort Sil, but died less than a year later.

The great chiefs are gone.

The mighty Kiowa and Comanche tribes were eroded, and the buffalo they had been trying to save disappeared.

All this happened in less than ten years.

--- p.369

Mad Horse died that night, September 5, 1877, at the age of thirty-five.

The next morning, the US military handed the chief's body over to his parents.

They placed their son's body in a wooden box, tied it to a horse-drawn travois, and carried it to the Spotted Tail Police Station, where it was placed on a dais.

The ancestors who mourned his death did not leave the place until the month of dry grass had passed.

Then, in the month when leaves were falling, heartbreaking news arrived.

“The Sioux must leave Nebraska and migrate to a new homeland on the Missouri River.”

On a dry, crisp autumn day in 1877, the Indians, under the watchful eye of the American army, embarked on a journey of exile to the barren wastes of the northeast, where not a blade of grass grew.

Along the way, some tribes broke away from the procession and turned northwest.

They planned to flee to Canada and join the Satso.

Among those who fled were the parents of Mad Horse, who had kept their son's heart and remains.

They buried their child's bones somewhere near a small creek they called Wounded Knee, a place only they knew, called Changkpe Opi Wakpala in the Sioux language.

--- p.419~420

The widows, orphans, and remaining warriors held captive at Fort Robinson were moved to Red Cloud Station on Pine Ridge, where they were joined by blunt swords, after months of delay due to the delays of Washington bureaucracy.

After waiting for several more months, the Cheyenne at Fort Kio were given a residence on the Tongue River, and the Dull Knife party, now reduced to a few men at Pine Ridge, was finally allowed to stay with the tribe.

But it was too late.

After all power was taken from the Cheyenne.

Since the Sand Creek Massacre, fate has dealt a devastating blow to this beautiful tribe.

The seeds of the tribe were scattered with the wind.

Before leaving the south, a warrior said:

“We will go north, risking everything.

Even if we die fighting, our names will remain deep in the hearts of our people.”

But soon there will be no one to remember them or call their names.

Now that beautiful tribe is gone.

--- p.467

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: June 20, 2024

- Page count, weight, size: 592 pages | 848g | 153*225*29mm

- ISBN13: 9791172130596

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)