Anthropology Classes to Discover Myself

|

Description

Book Introduction

“Shall I introduce myself?” is one of the questions that makes teenagers feel awkward.

Age, school, grades, hobbies, favorite idol… none of these things fully describe ‘me’.

Teenagers change from time to time, and I'm anxious that maybe I'm 'abnormal' because I'm not particularly good at anything.

How can we better understand ourselves, the most familiar yet perhaps even more elusive entity? Educational anthropologist Ham Se-jeong argues that exploring the very place where we stand—the society and culture surrounding us—better reveals who we are.

This is because the things that make up today's 'me' are created within the relationships I have, the large and small societies I belong to, and the influence of the culture that is taken for granted in those societies.

The author, who has met teenagers at the Haja Center's "Teen Research Institute" and studied the lives and culture of teenagers, explores the sociocultural context hidden in the obvious conclusions that "youth are like this, should be like this."

Based on the vivid voices and experiences of young people encountered in the field, this book reveals how narrow the framework of what adults and society consider "normal" or "common sense" is, and introduces anthropological concepts that make the obvious seem unfamiliar.

Building on key anthropological keywords such as cultural relativism, power, meaning, othering, and qualitative research, young readers will gain the courage to live differently from others and the strength to connect healthily with others, while richly interpreting themselves as sociocultural beings.

Age, school, grades, hobbies, favorite idol… none of these things fully describe ‘me’.

Teenagers change from time to time, and I'm anxious that maybe I'm 'abnormal' because I'm not particularly good at anything.

How can we better understand ourselves, the most familiar yet perhaps even more elusive entity? Educational anthropologist Ham Se-jeong argues that exploring the very place where we stand—the society and culture surrounding us—better reveals who we are.

This is because the things that make up today's 'me' are created within the relationships I have, the large and small societies I belong to, and the influence of the culture that is taken for granted in those societies.

The author, who has met teenagers at the Haja Center's "Teen Research Institute" and studied the lives and culture of teenagers, explores the sociocultural context hidden in the obvious conclusions that "youth are like this, should be like this."

Based on the vivid voices and experiences of young people encountered in the field, this book reveals how narrow the framework of what adults and society consider "normal" or "common sense" is, and introduces anthropological concepts that make the obvious seem unfamiliar.

Building on key anthropological keywords such as cultural relativism, power, meaning, othering, and qualitative research, young readers will gain the courage to live differently from others and the strength to connect healthily with others, while richly interpreting themselves as sociocultural beings.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Introduction: A new way to see myself

Part 1: Identity: We are diverse and complex beings.

1.

Youth is a constructed concept _ constructivism

2.

I want to meet someone who doesn't talk about college entrance exams _ Culture

3.

Am I Abnormal? - Cultural Relativism

4.

Living My Way _ Essentialism

5.

Edit Me _ Self-Identity

6.

Kids these days only care about themselves _ Typesetting

7.

Money is the best _ meaning

8.

Discovering Myself - Pop Culture

9.

Instead of K-genes _ nationalism

10.

People are deep _ qualitative research

Part 2 Society and Culture: Where Do I Stand?

1.

The world I see _ Positionality

2.

9th grade human _ meritocracy

3.

Classroom hierarchy _ power

4.

Are you a feminist? _ Gender

5.

Business Friends _ Social Relationships

6.

It's comfortable to be alone _ loneliness

7.

Even outside the family _ familism

8.

With poverty _ class

9.

Citizens who bring snacks _ Care

10.

A Good Life Outside of College _ Invisibility

Coming out: the hope of unpredictability

References

Part 1: Identity: We are diverse and complex beings.

1.

Youth is a constructed concept _ constructivism

2.

I want to meet someone who doesn't talk about college entrance exams _ Culture

3.

Am I Abnormal? - Cultural Relativism

4.

Living My Way _ Essentialism

5.

Edit Me _ Self-Identity

6.

Kids these days only care about themselves _ Typesetting

7.

Money is the best _ meaning

8.

Discovering Myself - Pop Culture

9.

Instead of K-genes _ nationalism

10.

People are deep _ qualitative research

Part 2 Society and Culture: Where Do I Stand?

1.

The world I see _ Positionality

2.

9th grade human _ meritocracy

3.

Classroom hierarchy _ power

4.

Are you a feminist? _ Gender

5.

Business Friends _ Social Relationships

6.

It's comfortable to be alone _ loneliness

7.

Even outside the family _ familism

8.

With poverty _ class

9.

Citizens who bring snacks _ Care

10.

A Good Life Outside of College _ Invisibility

Coming out: the hope of unpredictability

References

Detailed image

Into the book

Asking Questions About Normality/Abnormality Through Cultural Anthropology

In 2014, an Indian court recognized a third gender, including hijras, an intersex person who is neither male nor female, and guaranteed them the right to indicate this on official documents and avoid discrimination in employment, education, and other areas.

(…) Such court decisions reflect India’s cultural, historical and social context.

In other words, the fact that gender is divided into two categories, male and female, may not be an absolute standard, but rather a cultural standard.

Cultural anthropologists say that people who are considered abnormal in one culture may be normal in another.

(…) Teenagers are prone to becoming abnormal.

If you feel depressed, if you live with only one parent, if you are not interested in college entrance exams, if you have no friends, if you say you are a sexual minority, if you have no dreams, if you are a feminist, or if you are one year older than your classmates, you are abnormal.

There is nothing lacking in being a friend or colleague.

Interestingly, we became friends more easily and more deeply after we realized that we were both a little bit abnormal.

Questions about normal/abnormal might broaden your world a little.

By meeting more people and more of the world.

---p.

51~53

Does my own essence, a perfectly pure 'me', exist?

Creating my own identity is not my responsibility alone.

The process of becoming my own unique self is intertwined with the people I meet, the events I experience, the places I stay, and the groups I belong to.

(…) What happens if we understand the "self" from an essentialist perspective? We come to see the self, the core of our individuality, as inherently existing, and our lives as a process of recognizing or realizing that essence.

If we assume that there is a pure essence called 'I', then any encounter with the other is seen as an invasion of me, a dangerous thing that 'contaminates' my pure self.

(…) In cultural anthropology, essence is seen as a product of cultural beliefs rather than a natural fact or fixed entity.

The idea that black people are good at sports is not a biological truth, but a social understanding.

(…) Women’s maternal instincts can also be seen as a result of learned social expectations and gender roles rather than something that is expressed instinctively.

Likewise, the self is not a being with a specific essence, but rather a being that is constantly constructed and interpreted within relationships and contexts.

In other words, ‘self-identity’ is not something that is given from the beginning, but is formed and changed in the process of encountering others.

From this perspective, the other can be understood anew not as a being that threatens or contaminates me, but as a relational condition that creates me and a possibility for re-creation.

---p.

62~67

The danger of othering, of seeing others as "different" from oneself

The claim that "younger generations are self-centered" illustrates how one generation perceives others when they encounter people with different lifestyles and cultures.

Cultural anthropology, through the concept of othering, points out the danger of a perspective that emphasizes differences from other groups, that is, a perspective that sees others as "others" rather than as people similar to oneself.

This is because typification goes beyond simply recognizing 'difference' and leads to the process of assigning negative values to that difference and establishing hierarchy.

By defining others as “immoral,” “abnormal,” or “incomprehensible,” we establish our own identity as superior and normal.

(…) In the process of typification, the world is often divided into ‘us’ and ‘them.’

Here, 'they' often refers to social minorities.

The poor, women, the disabled, immigrants, black people, sexual minorities, and North Korean defectors become beings different from 'me'.

Their unique emotions, context, and subjectivity disappear, leaving only the 'essential' characteristics of the group.

Otherization is very problematic in that it regards them as a kind of object and subject.

---p.

81~88

Self-identity created through fandom

Being a fan of someone, that is, consuming and producing popular culture, can also be seen as a process of forming an identity.

(…) After hearing what their favorite songs are, what shows they enjoy watching, and whether there are any web novels they are waiting for, I feel like I get to know them a little better.

The pop culture content I like can be a way for me to express myself and create myself.

‘Deokjil’ is a process of forming self-identity.

In this way, identity, or who I become, can be seen as being created through the people I meet, the emotions I feel, and the places I visit.

(…) The experience of meeting people of different ages, occupations, regions, and sometimes even national backgrounds while doing fan activities plays a significant role in broadening their world.

I share stories that I would be reluctant to share even with my classmates with people I meet while doing fan activities, and I also share the joys and sorrows surrounding my fandom.

The fandom I belong to gives me a stronger sense of connection and belonging than the school I go to.

Because as fans, we experience important events together and share history.

(…) Through these experiences that expand emotionally, geographically, and socially, young people form their own identities.

---p.

107~112

My college entrance exam grade is only a small part of my story.

Many teenagers think, 'I am the problem.'

From a meritocratic perspective, rather than critically analyzing society and culture, we end up focusing on our own efforts and talents.

Everything becomes the individual's fault.

(…) A new perspective on ability is needed.

When we say someone is 'capable', the standards for that are not universal or unchanging, but vary depending on society and culture.

If we lived in a hunter-gatherer society today, what would we consider ability? There are many possible answers, but getting a high grade on the CSAT probably wouldn't be the most important.

(…) When we think back to the height of COVID-19, who were the people we relied on the most? (…) The sanitation workers who cleaned everything we touched in public places and collected trash, the delivery workers who delivered packages and food, the drivers who drove buses and taxis, the care workers who looked after the young or sick, the people who produced food ingredients—these so-called essential workers—were far more important.

These people were not previously considered 'capable'.

But in times of crisis, many people become dependent and contributing members of society.

(…) grades tell only a small part of the story about who you are, and you are a person with a much richer story than your score.

---p.

151~153

Power, the invisible force that creates the "popular" crowd

Power, as we know it in cultural anthropology, is a concept that permeates every corner of our lives.

It involves not just the forces that force us to follow someone, but also the invisible forces that influence what we consider 'normal' and what we consider 'good'.

Power doesn't just mean the strong oppressing the weak.

It also works by forming implicit standards for what to say and what to do, and by creating order.

For example, it appears as a way to manage and control the 'abnormal'.

What style of clothing is popular at school and what kind of speech style is used to determine who is considered an "insider" can also be seen as part of this power dynamic.

In other words, power is the force that shapes the way we see and act in the world, even in the most trivial of daily life.

---p.

167

I'm comfortable being alone, but I also want to be with you

Even though teenagers choose to be alone, they enjoy participating in 'rabang' (short for online real-time streaming broadcast, or live broadcast).

Explosive interaction and communication are some of the reasons people watch live broadcasts. According to a report by IT company Meta, interaction in live broadcasts increases tenfold compared to regular videos.

Digital natives, accustomed to creating stories collaboratively while connected, create and watch live broadcasts that allow for raw conversation and interaction, rather than edited and manipulated first-person footage.

It's rare for a host to talk on their own during a live broadcast without looking at the comments.

The flow of the story changes due to unplanned questions, and the screen changes according to the request to show something different.

We create stories together with the people we watch together.

The conversation continues as we admire each other on screen and exchange information.

(…) We are still connected, and we want to be connected.

---p.

199~200

Anthropologists' ethnography that captures the voices of the invisible

Invisibility refers to the phenomenon in which certain people or social phenomena are not properly recognized and treated as if they are invisible within a specific sociocultural context, despite their physical existence.

(…) Students attending four-year universities in Seoul account for only about 10 percent of the total, but they are considered a common presence in youth discourse.

Although more than 30 percent of people don't go to college, the main characters in romantic dramas all go to college.

(…) Among the youth, there are homeless youth, out-of-school youth who are not students, and homeless youth who live away from home, but these are not easily recognized because they are hidden in the typical image of youth.

(…) ‘Ethnography,’ a core research methodology in cultural anthropology, plays an important role in revealing these ‘invisible’ beings.

Ethnography is when anthropologists participate in cultural groups, observe them, hear their voices firsthand, and record them.

Ethnography contains stories and ways of life that are not heard in mainstream discourse.

This allows us to reveal and critically analyze social structural problems that have been overlooked so far.

Ethnography can go beyond simply making visible what is not there; it can challenge conventional notions of "normality" and help us understand the diverse possibilities of life and the complexities of society that we may not have previously been aware of.

In 2014, an Indian court recognized a third gender, including hijras, an intersex person who is neither male nor female, and guaranteed them the right to indicate this on official documents and avoid discrimination in employment, education, and other areas.

(…) Such court decisions reflect India’s cultural, historical and social context.

In other words, the fact that gender is divided into two categories, male and female, may not be an absolute standard, but rather a cultural standard.

Cultural anthropologists say that people who are considered abnormal in one culture may be normal in another.

(…) Teenagers are prone to becoming abnormal.

If you feel depressed, if you live with only one parent, if you are not interested in college entrance exams, if you have no friends, if you say you are a sexual minority, if you have no dreams, if you are a feminist, or if you are one year older than your classmates, you are abnormal.

There is nothing lacking in being a friend or colleague.

Interestingly, we became friends more easily and more deeply after we realized that we were both a little bit abnormal.

Questions about normal/abnormal might broaden your world a little.

By meeting more people and more of the world.

---p.

51~53

Does my own essence, a perfectly pure 'me', exist?

Creating my own identity is not my responsibility alone.

The process of becoming my own unique self is intertwined with the people I meet, the events I experience, the places I stay, and the groups I belong to.

(…) What happens if we understand the "self" from an essentialist perspective? We come to see the self, the core of our individuality, as inherently existing, and our lives as a process of recognizing or realizing that essence.

If we assume that there is a pure essence called 'I', then any encounter with the other is seen as an invasion of me, a dangerous thing that 'contaminates' my pure self.

(…) In cultural anthropology, essence is seen as a product of cultural beliefs rather than a natural fact or fixed entity.

The idea that black people are good at sports is not a biological truth, but a social understanding.

(…) Women’s maternal instincts can also be seen as a result of learned social expectations and gender roles rather than something that is expressed instinctively.

Likewise, the self is not a being with a specific essence, but rather a being that is constantly constructed and interpreted within relationships and contexts.

In other words, ‘self-identity’ is not something that is given from the beginning, but is formed and changed in the process of encountering others.

From this perspective, the other can be understood anew not as a being that threatens or contaminates me, but as a relational condition that creates me and a possibility for re-creation.

---p.

62~67

The danger of othering, of seeing others as "different" from oneself

The claim that "younger generations are self-centered" illustrates how one generation perceives others when they encounter people with different lifestyles and cultures.

Cultural anthropology, through the concept of othering, points out the danger of a perspective that emphasizes differences from other groups, that is, a perspective that sees others as "others" rather than as people similar to oneself.

This is because typification goes beyond simply recognizing 'difference' and leads to the process of assigning negative values to that difference and establishing hierarchy.

By defining others as “immoral,” “abnormal,” or “incomprehensible,” we establish our own identity as superior and normal.

(…) In the process of typification, the world is often divided into ‘us’ and ‘them.’

Here, 'they' often refers to social minorities.

The poor, women, the disabled, immigrants, black people, sexual minorities, and North Korean defectors become beings different from 'me'.

Their unique emotions, context, and subjectivity disappear, leaving only the 'essential' characteristics of the group.

Otherization is very problematic in that it regards them as a kind of object and subject.

---p.

81~88

Self-identity created through fandom

Being a fan of someone, that is, consuming and producing popular culture, can also be seen as a process of forming an identity.

(…) After hearing what their favorite songs are, what shows they enjoy watching, and whether there are any web novels they are waiting for, I feel like I get to know them a little better.

The pop culture content I like can be a way for me to express myself and create myself.

‘Deokjil’ is a process of forming self-identity.

In this way, identity, or who I become, can be seen as being created through the people I meet, the emotions I feel, and the places I visit.

(…) The experience of meeting people of different ages, occupations, regions, and sometimes even national backgrounds while doing fan activities plays a significant role in broadening their world.

I share stories that I would be reluctant to share even with my classmates with people I meet while doing fan activities, and I also share the joys and sorrows surrounding my fandom.

The fandom I belong to gives me a stronger sense of connection and belonging than the school I go to.

Because as fans, we experience important events together and share history.

(…) Through these experiences that expand emotionally, geographically, and socially, young people form their own identities.

---p.

107~112

My college entrance exam grade is only a small part of my story.

Many teenagers think, 'I am the problem.'

From a meritocratic perspective, rather than critically analyzing society and culture, we end up focusing on our own efforts and talents.

Everything becomes the individual's fault.

(…) A new perspective on ability is needed.

When we say someone is 'capable', the standards for that are not universal or unchanging, but vary depending on society and culture.

If we lived in a hunter-gatherer society today, what would we consider ability? There are many possible answers, but getting a high grade on the CSAT probably wouldn't be the most important.

(…) When we think back to the height of COVID-19, who were the people we relied on the most? (…) The sanitation workers who cleaned everything we touched in public places and collected trash, the delivery workers who delivered packages and food, the drivers who drove buses and taxis, the care workers who looked after the young or sick, the people who produced food ingredients—these so-called essential workers—were far more important.

These people were not previously considered 'capable'.

But in times of crisis, many people become dependent and contributing members of society.

(…) grades tell only a small part of the story about who you are, and you are a person with a much richer story than your score.

---p.

151~153

Power, the invisible force that creates the "popular" crowd

Power, as we know it in cultural anthropology, is a concept that permeates every corner of our lives.

It involves not just the forces that force us to follow someone, but also the invisible forces that influence what we consider 'normal' and what we consider 'good'.

Power doesn't just mean the strong oppressing the weak.

It also works by forming implicit standards for what to say and what to do, and by creating order.

For example, it appears as a way to manage and control the 'abnormal'.

What style of clothing is popular at school and what kind of speech style is used to determine who is considered an "insider" can also be seen as part of this power dynamic.

In other words, power is the force that shapes the way we see and act in the world, even in the most trivial of daily life.

---p.

167

I'm comfortable being alone, but I also want to be with you

Even though teenagers choose to be alone, they enjoy participating in 'rabang' (short for online real-time streaming broadcast, or live broadcast).

Explosive interaction and communication are some of the reasons people watch live broadcasts. According to a report by IT company Meta, interaction in live broadcasts increases tenfold compared to regular videos.

Digital natives, accustomed to creating stories collaboratively while connected, create and watch live broadcasts that allow for raw conversation and interaction, rather than edited and manipulated first-person footage.

It's rare for a host to talk on their own during a live broadcast without looking at the comments.

The flow of the story changes due to unplanned questions, and the screen changes according to the request to show something different.

We create stories together with the people we watch together.

The conversation continues as we admire each other on screen and exchange information.

(…) We are still connected, and we want to be connected.

---p.

199~200

Anthropologists' ethnography that captures the voices of the invisible

Invisibility refers to the phenomenon in which certain people or social phenomena are not properly recognized and treated as if they are invisible within a specific sociocultural context, despite their physical existence.

(…) Students attending four-year universities in Seoul account for only about 10 percent of the total, but they are considered a common presence in youth discourse.

Although more than 30 percent of people don't go to college, the main characters in romantic dramas all go to college.

(…) Among the youth, there are homeless youth, out-of-school youth who are not students, and homeless youth who live away from home, but these are not easily recognized because they are hidden in the typical image of youth.

(…) ‘Ethnography,’ a core research methodology in cultural anthropology, plays an important role in revealing these ‘invisible’ beings.

Ethnography is when anthropologists participate in cultural groups, observe them, hear their voices firsthand, and record them.

Ethnography contains stories and ways of life that are not heard in mainstream discourse.

This allows us to reveal and critically analyze social structural problems that have been overlooked so far.

Ethnography can go beyond simply making visible what is not there; it can challenge conventional notions of "normality" and help us understand the diverse possibilities of life and the complexities of society that we may not have previously been aware of.

--p.

248~250

248~250

Publisher's Review

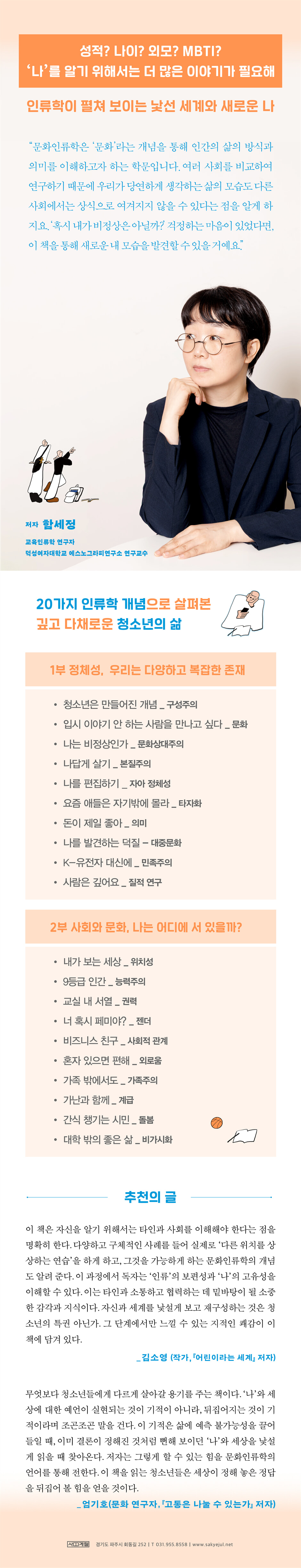

Grades? Age? Looks? MBTI?

More stories are needed to know 'me'

The unfamiliar world and new self that anthropology reveals

Teenagers often hear contradictory statements.

The words, “Find what you like and live ‘your own way’” and “Why can’t you do it like others?”

Before I even know who I am, I am simultaneously asked to be myself and to change who I am.

I feel hurt by comments that judge me based on a single factor, like grades or appearance, and I feel lost when I'm told to find my talent, aptitude, or self-identity.

Even though I continue to live as "me," why is it always so difficult to talk about myself? Isn't there a good way to understand who I am and rediscover aspects of myself I never knew existed?

Ham Se-jeong, an educational anthropologist who has worked with young people for a long time, says that in order to know oneself, one must look at the society and culture surrounding oneself rather than focusing on oneself.

Just as I am different at school than I am at home, and the traits that make a "good student" in a Korean classroom might be considered passive in other cultures, who I am depends on where I stand and who interprets me from what perspective.

Cultural anthropology is a discipline that serves as a good guide for exploring this society and culture.

Cultural anthropology is an academic discipline that seeks to understand the way and meaning of human life through the concept of 'culture'.

Because we study and compare different societies, we learn that the ways of life we take for granted may not be considered common sense in other societies.

Learning the perspective of cultural anthropology allows us to realize that the standards we consider natural are not universal across all societies, but rather were formed within specific environments and histories.

In other words, the evaluation and understanding of me can also differ from society to society.

(…) You are forming diverse identities through relationships in a variety of places, including school, online communities, neighborhoods, and families.

In it, my meaning becomes richer and deeper.

Cultural anthropology focuses on humans as multifaceted and complex beings.

- Pages 6-7

According to research by anthropologist Margaret Mead, Samoan adolescents grow up relatively easily, without experiencing the so-called "storm and stress" period, and do not show the typical adolescent tendencies of intense emotional swings and high anxiety.

In today's Korean society, teenagers are portrayed as unstable and immature, with terms like "middle school syndrome" and "adolescence." However, in the past, they were also active as leaders of the independence and democratization movements.

In other words, even the concept of ‘youth’ is defined differently depending on society, culture, and era.

This book makes us look at the various terms that define teenagers—students, children, Koreans, someone's fan, business friend, and some level of human—from a cultural anthropological perspective in a new light.

By confronting questions like, "Who is Korean?", "How have my experiences and the people I've met while liking idols changed me?", and "How much can my grades really describe me?", young people can imagine where and who they are, how they would be different if they were in a different place, and how people in different positions view the world.

An anthropological perspective that respects the unique characteristics of each society and culture shows us that the standards and indicators required of today's Korean youth are by no means absolute truths, and that we can always write new stories.

If you were a teenager who feared that you might be abnormal because you weren't interested in college entrance exams, liked being alone, hated your family, and had no dreams, this book will help you understand the sociocultural context that fostered those fears and create a deep and rich story about yourself.

Cultural relativism, positionality, othering, meaning, qualitative research, gender, invisibility…

The Deep and Colorful Lives of Adolescents Through 20 Anthropological Concepts

This book is an introductory text introducing the perspectives and concepts of cultural anthropology to young people, and at the same time, it is a field record containing the perspectives and experiences of young people living in today's Korean society.

In this book, the author has included the specific lives of youth that he has seen, heard, and experienced firsthand at the Migrant Youth Support Foundation, Haja Center, and university lecture halls.

Just as anthropological research reveals stories and ways of life that have gone unheard, obscured by society's dominant narratives, this book vividly reveals the honest thoughts, uninhibited words, and hidden pain and anxiety of young people who have often been hidden from view because they lack sufficient rights and a voice in society.

This book, consisting of 20 articles, introduces 20 cultural anthropology concepts that can be used to interpret the daily lives of today's youth from various angles, including college entrance exams, the online world, classroom hierarchy, friendships, and idol fandom culture.

For example, we examine the position of a teenager who feels “intimidated” or “will I get in trouble?” when adults say, “Let’s talk,” through the concept of “positionality.”

Dialogue is a democratic communication method for resolving conflicts and building healthy relationships, but why do teenagers react this way? This is because adults and teenagers enter the conversation with different experiences, resources, and information.

For relatively vulnerable adolescents, conversation can feel like a kind of interrogation or test, and explaining themselves in a language that adults can understand can feel burdensome.

This is what anthropology calls 'positionality', where the world looks different depending on where and who I am.

We each experience the world and form relationships from different positions, depending on our nationality, age, education level, gender identity, class, and life experiences.

Therefore, if we understand 'positionality,' we can realize that our perspective is not everything, and we can be more open to other opinions from other positions.

My perspective, experience, and knowledge about the world may vary depending on my position.

In American history, for example, the era of the Wild West, which brings to mind cowboys galloping to the sound of exciting music, can be understood from the perspective of Native Americans as a history of invasion, massacre, and suffering that forced them to leave their homes.

Career education can also be perceived differently depending on the student's position.

For undocumented immigrant youth, conventional career theories may not be as effective.

For someone living an uncertain life due to visa issues, the advice to have a clear career goal and work towards it would be unrealistic.

- Pages 145-146

Meanwhile, if we examine the words of young people who cite money as the top criterion for choosing a career through the concept of sociocultural 'meaning' that is noted in anthropology, 'money' does not simply mean economic freedom.

Hidden within it lie various desires, longings, and sociocultural contexts, such as the minimum level of stability desired in an era where unstable employment has become the norm, the desire to avoid questions from adults who only recognize a small number of occupations as "dreams," and the desire not to live a life solely focused on work.

Just as the act of purchasing the latest smartphone is associated with rich meanings such as social status, a sense of belonging, tastes, and self-identity in addition to the smartphone's functionality, humans live by overlaying the "meaning" they share on top of the physical world through language, symbols, stories, and rituals.

Therefore, if we look into the daily lives of teenagers through the concept of 'meaning', we can see teenagers not as predictable and obvious people, but as beings with multi-layered and complex inner lives.

Because 'money' is a medium of exchange, it always means the next thing.

Many of life's values are hidden beneath the umbrella of "money," such as time to meet friends, the freedom to return the favors they've received, opportunities to gain experience, and time to maintain good health.

So, the question about 'money' needs to be asked.

Rather than turning young people into shallow people who only care about money, we need to uncover the rich meaning hidden in money.

(…) Sociocultural meanings form the basis for our understanding of the world.

Furthermore, it is connected to the questions, ‘What is important and valuable?’ and ‘How should we live?’

From this perspective, the fact that Korean youth prioritize 'income' as a criterion for choosing a career can be seen as a phenomenon that goes beyond personal preference and reflects our society and culture.

- Pages 97-101

In addition, this book teaches young people how to find their own uniqueness by going against the common sense and conventions of society and understanding and respecting others as beings with their own unique world through key concepts of cultural anthropology, such as 'cultural relativism', which considers that the standards of normal and abnormal differ depending on the unique cultural context of each society; 'qualitative research', which deeply explores a person's emotions, experiences, and values through interviews or field research; and 'othering', which defines a specific group as different beings with fundamentally different characteristics rather than beings equal to oneself.

Moreover, it makes non-teen readers realize that the descriptions of teenagers as “self-indulgent” and “middle school syndrome” are actually closely connected to the world that teenagers experience and the position they stand in.

Young and non-young readers who read this book together will find that they are quite closely connected to each other, and that despite their differences, they can understand and connect with each other.

The hope of unpredictability

The power and courage that an anthropological perspective gives to youth

The anthropological perspective that we can interpret the world differently based on our innate identity, social position, historical experience, and resources, and that these interpretations are constantly changing, can provide a liberating perspective for young people.

This is because many of the things that put pressure on young people, such as dreams, college entrance exams, career paths, and identity, can be understood not as absolute realities, but as fluid and cultural products that can be viewed differently and transformed.

For young people who believed that their family background, talents, friends, and future were all already decided and that there were no other possibilities, anthropology taught them that 'the world is not a place where everything has already been decided.

We can tell the story that we can create new things, both society and culture, both normal and abnormal.

The author describes this as “the hope of unpredictability.”

Poor grades, no money, no friends, a sexual identity that must be hidden, a world that seems doomed to destruction by climate crisis or war—these are all vivid pessimisms for teenagers, but anthropologists have proven through numerous studies that the world always goes in a different direction than expected.

Even cultures that seemed strange can be understood when you delve into them, and people you believed held opposing views can be found to have many similarities with you through in-depth conversations through interviews.

Depending on who stands and where they are looking, the situation changes, and when the situation changes, the relationship also enters a new phase.

Learning the anthropological perspective allows us to see that we, others, and the world are all dynamic processes that we can create together, with no set conclusion.

Furthermore, you can have the courage to go beyond the established framework and create a new you and a new world.

The fact that predictions can be wrong provides a clue that can overturn pessimistic determinism.

If there is a miracle, it is the changing of prophecy.

Fortunately, this 'miracle' occurs frequently in cultural anthropological research.

Policies that were carefully crafted often lead to overturned outcomes, students behave differently from the teacher's intentions, and research is filled with scenes that researchers never imagined.

Movements within a concrete context have special possibilities that cannot be replaced by rules and formulas.

(…) I wanted to help people discover a new side of themselves, beyond the self defined as ‘deficient, ugly, and abnormal.’

Discovering the unexpected side of myself may be a miracle that overturns my conclusions about myself.

I hope this book helps you move beyond established answers and begin a new story.

- Pages 254-255

More stories are needed to know 'me'

The unfamiliar world and new self that anthropology reveals

Teenagers often hear contradictory statements.

The words, “Find what you like and live ‘your own way’” and “Why can’t you do it like others?”

Before I even know who I am, I am simultaneously asked to be myself and to change who I am.

I feel hurt by comments that judge me based on a single factor, like grades or appearance, and I feel lost when I'm told to find my talent, aptitude, or self-identity.

Even though I continue to live as "me," why is it always so difficult to talk about myself? Isn't there a good way to understand who I am and rediscover aspects of myself I never knew existed?

Ham Se-jeong, an educational anthropologist who has worked with young people for a long time, says that in order to know oneself, one must look at the society and culture surrounding oneself rather than focusing on oneself.

Just as I am different at school than I am at home, and the traits that make a "good student" in a Korean classroom might be considered passive in other cultures, who I am depends on where I stand and who interprets me from what perspective.

Cultural anthropology is a discipline that serves as a good guide for exploring this society and culture.

Cultural anthropology is an academic discipline that seeks to understand the way and meaning of human life through the concept of 'culture'.

Because we study and compare different societies, we learn that the ways of life we take for granted may not be considered common sense in other societies.

Learning the perspective of cultural anthropology allows us to realize that the standards we consider natural are not universal across all societies, but rather were formed within specific environments and histories.

In other words, the evaluation and understanding of me can also differ from society to society.

(…) You are forming diverse identities through relationships in a variety of places, including school, online communities, neighborhoods, and families.

In it, my meaning becomes richer and deeper.

Cultural anthropology focuses on humans as multifaceted and complex beings.

- Pages 6-7

According to research by anthropologist Margaret Mead, Samoan adolescents grow up relatively easily, without experiencing the so-called "storm and stress" period, and do not show the typical adolescent tendencies of intense emotional swings and high anxiety.

In today's Korean society, teenagers are portrayed as unstable and immature, with terms like "middle school syndrome" and "adolescence." However, in the past, they were also active as leaders of the independence and democratization movements.

In other words, even the concept of ‘youth’ is defined differently depending on society, culture, and era.

This book makes us look at the various terms that define teenagers—students, children, Koreans, someone's fan, business friend, and some level of human—from a cultural anthropological perspective in a new light.

By confronting questions like, "Who is Korean?", "How have my experiences and the people I've met while liking idols changed me?", and "How much can my grades really describe me?", young people can imagine where and who they are, how they would be different if they were in a different place, and how people in different positions view the world.

An anthropological perspective that respects the unique characteristics of each society and culture shows us that the standards and indicators required of today's Korean youth are by no means absolute truths, and that we can always write new stories.

If you were a teenager who feared that you might be abnormal because you weren't interested in college entrance exams, liked being alone, hated your family, and had no dreams, this book will help you understand the sociocultural context that fostered those fears and create a deep and rich story about yourself.

Cultural relativism, positionality, othering, meaning, qualitative research, gender, invisibility…

The Deep and Colorful Lives of Adolescents Through 20 Anthropological Concepts

This book is an introductory text introducing the perspectives and concepts of cultural anthropology to young people, and at the same time, it is a field record containing the perspectives and experiences of young people living in today's Korean society.

In this book, the author has included the specific lives of youth that he has seen, heard, and experienced firsthand at the Migrant Youth Support Foundation, Haja Center, and university lecture halls.

Just as anthropological research reveals stories and ways of life that have gone unheard, obscured by society's dominant narratives, this book vividly reveals the honest thoughts, uninhibited words, and hidden pain and anxiety of young people who have often been hidden from view because they lack sufficient rights and a voice in society.

This book, consisting of 20 articles, introduces 20 cultural anthropology concepts that can be used to interpret the daily lives of today's youth from various angles, including college entrance exams, the online world, classroom hierarchy, friendships, and idol fandom culture.

For example, we examine the position of a teenager who feels “intimidated” or “will I get in trouble?” when adults say, “Let’s talk,” through the concept of “positionality.”

Dialogue is a democratic communication method for resolving conflicts and building healthy relationships, but why do teenagers react this way? This is because adults and teenagers enter the conversation with different experiences, resources, and information.

For relatively vulnerable adolescents, conversation can feel like a kind of interrogation or test, and explaining themselves in a language that adults can understand can feel burdensome.

This is what anthropology calls 'positionality', where the world looks different depending on where and who I am.

We each experience the world and form relationships from different positions, depending on our nationality, age, education level, gender identity, class, and life experiences.

Therefore, if we understand 'positionality,' we can realize that our perspective is not everything, and we can be more open to other opinions from other positions.

My perspective, experience, and knowledge about the world may vary depending on my position.

In American history, for example, the era of the Wild West, which brings to mind cowboys galloping to the sound of exciting music, can be understood from the perspective of Native Americans as a history of invasion, massacre, and suffering that forced them to leave their homes.

Career education can also be perceived differently depending on the student's position.

For undocumented immigrant youth, conventional career theories may not be as effective.

For someone living an uncertain life due to visa issues, the advice to have a clear career goal and work towards it would be unrealistic.

- Pages 145-146

Meanwhile, if we examine the words of young people who cite money as the top criterion for choosing a career through the concept of sociocultural 'meaning' that is noted in anthropology, 'money' does not simply mean economic freedom.

Hidden within it lie various desires, longings, and sociocultural contexts, such as the minimum level of stability desired in an era where unstable employment has become the norm, the desire to avoid questions from adults who only recognize a small number of occupations as "dreams," and the desire not to live a life solely focused on work.

Just as the act of purchasing the latest smartphone is associated with rich meanings such as social status, a sense of belonging, tastes, and self-identity in addition to the smartphone's functionality, humans live by overlaying the "meaning" they share on top of the physical world through language, symbols, stories, and rituals.

Therefore, if we look into the daily lives of teenagers through the concept of 'meaning', we can see teenagers not as predictable and obvious people, but as beings with multi-layered and complex inner lives.

Because 'money' is a medium of exchange, it always means the next thing.

Many of life's values are hidden beneath the umbrella of "money," such as time to meet friends, the freedom to return the favors they've received, opportunities to gain experience, and time to maintain good health.

So, the question about 'money' needs to be asked.

Rather than turning young people into shallow people who only care about money, we need to uncover the rich meaning hidden in money.

(…) Sociocultural meanings form the basis for our understanding of the world.

Furthermore, it is connected to the questions, ‘What is important and valuable?’ and ‘How should we live?’

From this perspective, the fact that Korean youth prioritize 'income' as a criterion for choosing a career can be seen as a phenomenon that goes beyond personal preference and reflects our society and culture.

- Pages 97-101

In addition, this book teaches young people how to find their own uniqueness by going against the common sense and conventions of society and understanding and respecting others as beings with their own unique world through key concepts of cultural anthropology, such as 'cultural relativism', which considers that the standards of normal and abnormal differ depending on the unique cultural context of each society; 'qualitative research', which deeply explores a person's emotions, experiences, and values through interviews or field research; and 'othering', which defines a specific group as different beings with fundamentally different characteristics rather than beings equal to oneself.

Moreover, it makes non-teen readers realize that the descriptions of teenagers as “self-indulgent” and “middle school syndrome” are actually closely connected to the world that teenagers experience and the position they stand in.

Young and non-young readers who read this book together will find that they are quite closely connected to each other, and that despite their differences, they can understand and connect with each other.

The hope of unpredictability

The power and courage that an anthropological perspective gives to youth

The anthropological perspective that we can interpret the world differently based on our innate identity, social position, historical experience, and resources, and that these interpretations are constantly changing, can provide a liberating perspective for young people.

This is because many of the things that put pressure on young people, such as dreams, college entrance exams, career paths, and identity, can be understood not as absolute realities, but as fluid and cultural products that can be viewed differently and transformed.

For young people who believed that their family background, talents, friends, and future were all already decided and that there were no other possibilities, anthropology taught them that 'the world is not a place where everything has already been decided.

We can tell the story that we can create new things, both society and culture, both normal and abnormal.

The author describes this as “the hope of unpredictability.”

Poor grades, no money, no friends, a sexual identity that must be hidden, a world that seems doomed to destruction by climate crisis or war—these are all vivid pessimisms for teenagers, but anthropologists have proven through numerous studies that the world always goes in a different direction than expected.

Even cultures that seemed strange can be understood when you delve into them, and people you believed held opposing views can be found to have many similarities with you through in-depth conversations through interviews.

Depending on who stands and where they are looking, the situation changes, and when the situation changes, the relationship also enters a new phase.

Learning the anthropological perspective allows us to see that we, others, and the world are all dynamic processes that we can create together, with no set conclusion.

Furthermore, you can have the courage to go beyond the established framework and create a new you and a new world.

The fact that predictions can be wrong provides a clue that can overturn pessimistic determinism.

If there is a miracle, it is the changing of prophecy.

Fortunately, this 'miracle' occurs frequently in cultural anthropological research.

Policies that were carefully crafted often lead to overturned outcomes, students behave differently from the teacher's intentions, and research is filled with scenes that researchers never imagined.

Movements within a concrete context have special possibilities that cannot be replaced by rules and formulas.

(…) I wanted to help people discover a new side of themselves, beyond the self defined as ‘deficient, ugly, and abnormal.’

Discovering the unexpected side of myself may be a miracle that overturns my conclusions about myself.

I hope this book helps you move beyond established answers and begin a new story.

- Pages 254-255

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: July 25, 2025

- Page count, weight, size: 260 pages | 392g | 140*200*16mm

- ISBN13: 9791169813853

- ISBN10: 1169813852

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)