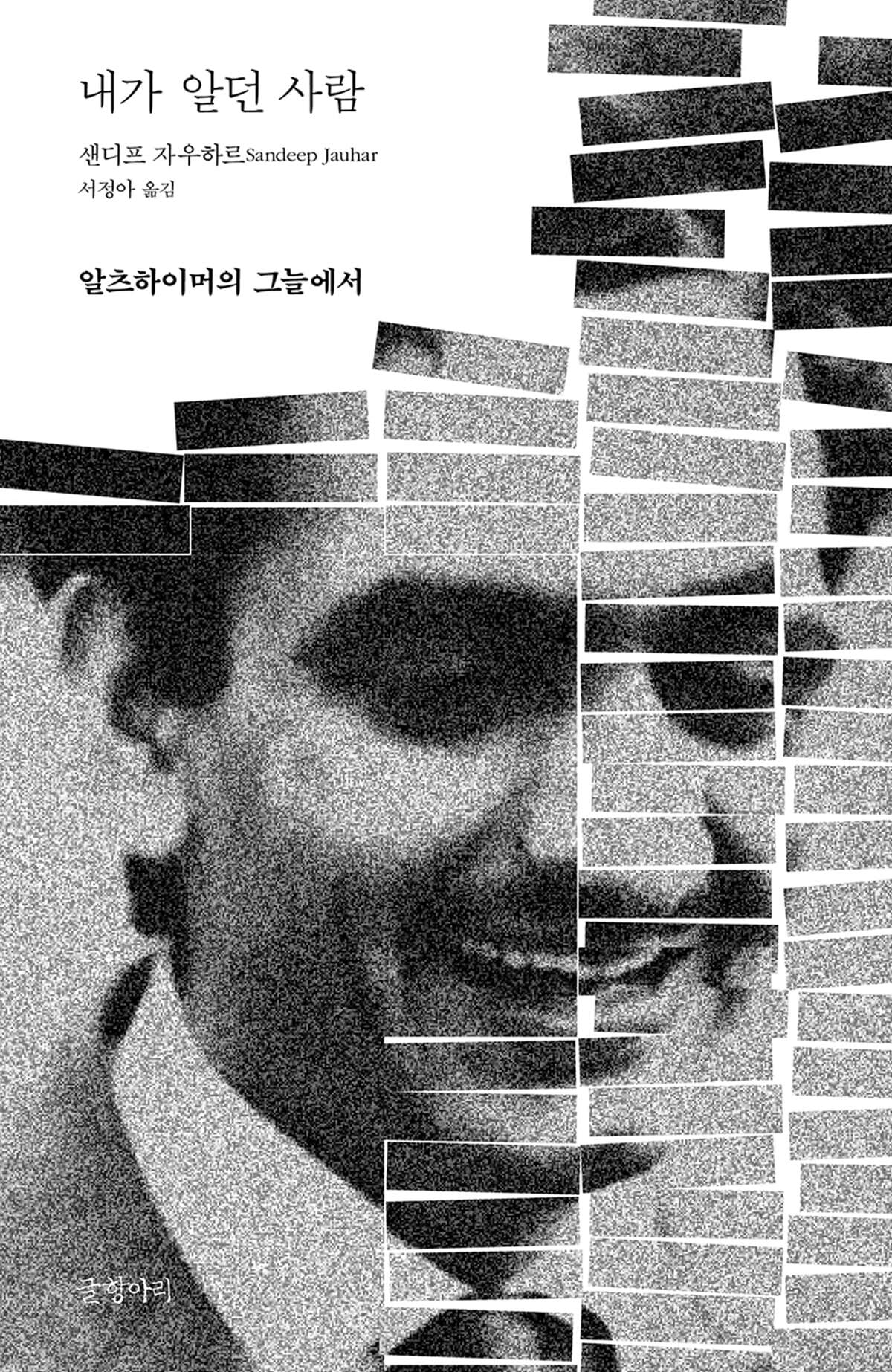

Someone I knew

|

Description

Book Introduction

'Don't forget me. … … Even if I forget myself.' Seven Years of Alzheimer's Care: A Memoir of Humor and Heartbreak The New Yorker's 2023 Books of the Year Smithsonian's 2023 Science Book of the Year Is a life without memories still a life? Disappearing memories and collapsing egos, And the relationships and existence that are reconstructed beyond memory Prem Jauhar, an Indian-American scientist, began to blink frequently one day. I couldn't remember the names of people I'd known for a long time, and the password to my new safe was hazy. For a while, I just thought it was a natural decline in memory that came with age and didn't take it seriously, but soon after, I started to see signs that were more serious than normal forgetfulness. At gatherings, we would often repeat the same stories over and over again, faces in family photos would suddenly seem unfamiliar, and there were days when we would go out and get lost because we couldn't find our way home. The wife called her sons home and had them take him to a neurologist. From there, the journey of this book began. "The Man I Used to Know: In the Shadow of Alzheimer's" is a book written by Prem's second son, cardiologist Sandeep Jauhar, who looks back on his father, who suffered from Alzheimer's disease for seven years starting in the fall of 2014, and lost his memory, the world, and ultimately himself. This memoir is, of course, a painfully honest confession about the dynamics of relationships and care. It is simultaneously a medical exploration of brain degeneration and mental erosion, and a reflection on the way memory gives meaning to our lives. |

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Introduction: Everyone said I was a genius.

Part 1: About the Class and Knots

Chapter 1_ We can move to Georgia anytime

Chapter 2_ So, when are you going to bring Pia?

Chapter 3_ Then I'll take a taxi

Chapter 4_ Well, I guess the name will remain later.

Chapter 5_ When I leave someday, I'll leave everything behind anyway.

Chapter 6: It is difficult to deny the special nature of the disease being discussed here.

Chapter 7: This day has finally come.

Part 2 Traces

Chapter 8_ Do you want to lock your father in a nursing home like your grandmother?

Chapter 9: I'm going to work for free from now on.

Chapter 10_ Well, don't worry about loneliness!

Chapter 11_ Where is your mother?

Chapter 12_ It's none of my business whether you know math or not.

Chapter 13: You are my family

Chapter 14: Don't worry, everything will be alright.

Acknowledgements

Search

Part 1: About the Class and Knots

Chapter 1_ We can move to Georgia anytime

Chapter 2_ So, when are you going to bring Pia?

Chapter 3_ Then I'll take a taxi

Chapter 4_ Well, I guess the name will remain later.

Chapter 5_ When I leave someday, I'll leave everything behind anyway.

Chapter 6: It is difficult to deny the special nature of the disease being discussed here.

Chapter 7: This day has finally come.

Part 2 Traces

Chapter 8_ Do you want to lock your father in a nursing home like your grandmother?

Chapter 9: I'm going to work for free from now on.

Chapter 10_ Well, don't worry about loneliness!

Chapter 11_ Where is your mother?

Chapter 12_ It's none of my business whether you know math or not.

Chapter 13: You are my family

Chapter 14: Don't worry, everything will be alright.

Acknowledgements

Search

Into the book

Even as I drove back from Dr. Gordon's office that chilly November day, I had no idea of the details of what was about to unfold.

But as a doctor, I knew that the disease would eventually be defeated.

There was no hope for unexpected results or miracles.

It was a fight that was sure to end in defeat.

The only question in my mind was how many sacrifices would be required before defeat.

--- From "Introduction: Everyone Said I Was a Genius"

Sadly, the malignant social psychology that led to my father's isolation was even permeated by his family.

I would like to say that, compared to the outside world, we were generous to our father.

But in reality, that wasn't the case.

Father's flickering mind confined him to an eternal present while imprisoning his children in eternal resignation.

Whenever my father asked us questions, we would scold him, saying that he wouldn't be able to remember the answers anyway, so what's the use of asking him questions?

These are scenes I really want to forget.

Sometimes we would talk about our father among ourselves as if he wasn't there.

“Father is out of control.” “He probably doesn’t remember.” “He’s like a little child now.” We would say things like that to our father’s face, sometimes even at him.

And after that, we regretted it again and again, but we didn't know how to restrain ourselves.

Of course, we knew that our father was more than just a damaged brain.

I knew it all, but it wasn't easy to accept it as fact.

--- From "Chapter 8: Do you want to lock your father in a nursing home like your grandmother?"

For my father, the loss of the ability to recognize his illness was essentially a defense mechanism.

In a way, the bottle was protecting his ailing father.

There were other comforting facts.

We were able to alleviate some of my father's anxiety by lying about things that never happened (I had long since gotten over my reluctance to lie to him, too).

For example, when Rajiv went on a trip without telling his father, he would lie and say that he had called him in advance and left.

Moreover, my father no longer got angry over things that would have made him angry in the past.

Most arguments are forgotten as soon as you turn around.

My father would deny something or reprimand me for it, but he never dwelled on it for long.

Because he had virtually no short-term memory, my father lived his life in a kind of hallucination.

Within minutes, sometimes even more quickly, my father's mood could shift from fury to resignation to something akin to joy, or at least to wit or playfulness—a kind of playfulness I'd never seen growing up.

--- From "Chapter 10: Well, Don't Worry About Loneliness!"

“Then what should I do?” I asked, even though I knew the answer.

“I would never give you an IV,” Jasmine answered firmly.

“I think Father wanted to tell his children that when this day comes, they should just let him go.” We sat in silence for a few minutes.

My brother came into the room.

“So what did you decide to do?” I turned my head to look at my brother’s confident and confident appearance.

We've always had such different ways of responding to problems.

My brother had very low tolerance for indecision.

As a guardian with a surgeon's mindset, my brother knew exactly what steps to take, and it seemed his patience was running out to wait for me to figure it out on my own.

I had no choice but to shake my head.

“You decide, hyung.” “Please remove the IV drip.” As if he had been waiting for this, hyung left Jasmine with these words and immediately left.

But as a doctor, I knew that the disease would eventually be defeated.

There was no hope for unexpected results or miracles.

It was a fight that was sure to end in defeat.

The only question in my mind was how many sacrifices would be required before defeat.

--- From "Introduction: Everyone Said I Was a Genius"

Sadly, the malignant social psychology that led to my father's isolation was even permeated by his family.

I would like to say that, compared to the outside world, we were generous to our father.

But in reality, that wasn't the case.

Father's flickering mind confined him to an eternal present while imprisoning his children in eternal resignation.

Whenever my father asked us questions, we would scold him, saying that he wouldn't be able to remember the answers anyway, so what's the use of asking him questions?

These are scenes I really want to forget.

Sometimes we would talk about our father among ourselves as if he wasn't there.

“Father is out of control.” “He probably doesn’t remember.” “He’s like a little child now.” We would say things like that to our father’s face, sometimes even at him.

And after that, we regretted it again and again, but we didn't know how to restrain ourselves.

Of course, we knew that our father was more than just a damaged brain.

I knew it all, but it wasn't easy to accept it as fact.

--- From "Chapter 8: Do you want to lock your father in a nursing home like your grandmother?"

For my father, the loss of the ability to recognize his illness was essentially a defense mechanism.

In a way, the bottle was protecting his ailing father.

There were other comforting facts.

We were able to alleviate some of my father's anxiety by lying about things that never happened (I had long since gotten over my reluctance to lie to him, too).

For example, when Rajiv went on a trip without telling his father, he would lie and say that he had called him in advance and left.

Moreover, my father no longer got angry over things that would have made him angry in the past.

Most arguments are forgotten as soon as you turn around.

My father would deny something or reprimand me for it, but he never dwelled on it for long.

Because he had virtually no short-term memory, my father lived his life in a kind of hallucination.

Within minutes, sometimes even more quickly, my father's mood could shift from fury to resignation to something akin to joy, or at least to wit or playfulness—a kind of playfulness I'd never seen growing up.

--- From "Chapter 10: Well, Don't Worry About Loneliness!"

“Then what should I do?” I asked, even though I knew the answer.

“I would never give you an IV,” Jasmine answered firmly.

“I think Father wanted to tell his children that when this day comes, they should just let him go.” We sat in silence for a few minutes.

My brother came into the room.

“So what did you decide to do?” I turned my head to look at my brother’s confident and confident appearance.

We've always had such different ways of responding to problems.

My brother had very low tolerance for indecision.

As a guardian with a surgeon's mindset, my brother knew exactly what steps to take, and it seemed his patience was running out to wait for me to figure it out on my own.

I had no choice but to shake my head.

“You decide, hyung.” “Please remove the IV drip.” As if he had been waiting for this, hyung left Jasmine with these words and immediately left.

--- From "Chapter 14: Don't Worry, Everything Will Be Okay"

Publisher's Review

Memory changes

The way of being and the conclusion of relationships

The original title of this book is My Father's Brain.

From the moment his father was diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease, Sandeep Jauhar embarked on a solo quest to understand his brain and the brains of others with dementia.

He says this book is a journey of that exploration.

Although this is a largely medical expression, this journey ultimately becomes a story about life itself, accumulated as a mental entity, the complexly intertwined human relationships within it, and memory and human existence, as the subject of its exploration is the 'brain'.

It also serves as an example of how one person can continue to be that person (even if he or she cannot be that person to himself or herself) even when things are shaking and collapsing.

This book is (…) about my relationship with my father, especially my relationship with him as he was falling apart from illness in the final stages of his life.

The book is also about the challenges that arise when family members must take on the role of caregiver, the bonds between parents, and the challenges that test those bonds.

The conversations and debates in the book are personal yet profoundly universal.

Perhaps it's a typical example of the conversations and arguments a family might have when confronted with the mental erosion of an adult in the family. But this book goes beyond these personal stories to discuss the brain and memory.

We discuss how and why the brain deteriorates as we age, and explore how we give meaning to our lives even as our memories fade and change with the passage of time.

We also explore how the concept of what it means to be human becomes more complex due to dementia, and the implications this has for patients, their families, and society as a whole (26-27).

While caring for her father, who suffers from dementia, the author witnesses firsthand the loss and confusion he faces in his daily life.

As if responding to his father's gaze that seemed to say, "Don't forget me," he decided to remember him by using his family's history and his own memories.

And in a way I had never thought about before, I re-established my relationship with my father, becoming aware of the obvious and fundamental conditions of human existence, life and death.

“It was a truly dramatic change,” the author says (19).

My father, who was a world-renowned scientist studying wheat genetics in his own laboratory just a few months ago, was diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment. Within a few years, he had lost the ability to remember himself and ultimately, even how to breathe. What happened to him and his family went beyond the painful coping mechanisms of fighting the illness and caring for him.

The 'dramatic change' came not only to my father's brain, but also to my family relationships, and it was a process of managing relationships and managing life much more actively, perhaps even combatively, than I had thought.

As my knowledge grew, I was able to delve deeper into my father's world.

And I was able to bridge a little of the gap between us, a gap that I had tried my whole life to bridge but could never seem to close.

Yet, I think that road was the most difficult one of my life.

For nearly seven years I have been urging and urging, threatening and cajoling, pleading and entreating, encouraging and ridiculing.

I forced my father to go for walks, bought him books and gave him a hug, and forced him to do puzzles.

I loved and cherished my father, but at the same time I hated him.

'Don't forget me,' my father's eyes seemed to say.

Therefore, as a son, I decided to preserve my father's memories as much as possible.

As a result, I learned more about my father, what kind of person he was, what his likes and dislikes, than you did.

Looking back, it was a strange sense of responsibility.

Whenever I went to gatherings, I would always mention that my father had written books and received academic awards.

In that way, I was reminding everyone that your father is bigger than the illness that afflicts him.

(27-28)

Meanwhile, the paradoxical fact that from the moment your father began to lose himself in you, your son's understanding began to develop in a different way and a relationship that had previously been impossible was formed shows that memory is a more complex concept than you might think.

'What is memory, anyway?' This question constantly changes its form throughout the book, functioning as akin to 'Who are we?'

Just as Lenny, the protagonist of the movie "Memento," who suffered from anterograde amnesia, ended up destroying the note that revealed the real culprit who killed his wife, memory can sometimes become the purpose of life itself.

Reflecting on the identity, meaning, and networks of memory, the author uses the essence of memory to reconstruct relationships.

Our memories exist in many places.

Memories live in books, on hard drives, on smartphones, and in other independent entities outside our minds.

Even memories may be shared between more than one brain, such as the brains of several members of a family.

If the primary brain fails to remember, other brains may inevitably take over the task. (97)

As my father was carried out and people began to cry, a strange memory came flooding back to me.

It was a memory from the year after my family came to America.

I was nine years old at the time and was learning to ride a bike on the dusty hillside behind my old Kentucky home.

(…) My father, who I usually remember that day, lost interest as soon as he decided that I could go down the hill by myself and went inside.

But in my memory of that sunny March morning, when I was holding onto my father's lifeless body, for some reason, he was also running beside me.

I pedaled hard down the hill along the rutted path, covered with branches and weeds, with my father keeping pace with me so I wouldn't fall.

I knew that memory was not true, that it could not be true.

But now it has become my memory.

I decided to keep that memory. (340)

He redefines the existence of his father within himself through the concept of memory and the resource of recollection, and redefines the relationship by revising the memories of his childhood that are in some way connected to the time in his later years when he spent the most time with him, caring for him. However, the way this book reveals its virtue is paradoxically the boundary thinking that the author shows.

While he cites the main lines of Western philosophy that view humans as a collection of memories and minds, he points out that “if we define humans solely based on their mental lives, we run the risk of falling into the trap of dehumanization” (245).

How can the integrity of a few neural clusters determine whether a person has a personality, and therefore whether they deserve the rights, moral protections, and respect that come with being human? How can such a crucial characteristic be determined by a mere few brain regions? Incidentally, there is a philosophical perspective that counters this trend.

In short, the psychological 'continuity' that is considered the basis of personality is, however, by no means continuous.

For example, I may not remember something I experienced in my childhood, but I remember something from my youth, and in my youth, I remembered something I experienced in my childhood.

Therefore, if the current me is the same person as the me in my youth, and the me in my youth is the same person as the me in my childhood, then even if there is no psychological continuity, I cannot help but still be the same person as the me in my childhood.

Therefore, of course, memory alone cannot fully determine an individual's identity.

(…) We were still connected by common family ties and a common life story.

Although there were times when my father himself could not remember the family relationships or life story in question.

Nevertheless, he was my father.

Because I thought of Him as my father. (246-247)

A disease 'more frightening than death'

The Shadow of Alzheimer's

If the recollection of one's father is the central theme of "The Person I Used to Know," the discussion of Alzheimer's disease is a side story.

The author, a cardiologist, uses his literary skills, as in “Heart,” to appropriately present a medical narrative on the brain, memory, and Alzheimer’s disease.

From ancient times, when dementia was considered to be a “phantom” or “accumulation of black bile” (Aristotle) or “the result of the coldness of the humors” (Galen), to modern times, when dementia patients were locked up “with ‘the idiots [and] the epileptics and paralytics,’ prostitutes, and various ‘perverts’” and “dunked in cold water or whipped,” to the naming of the disease and the ongoing treatment research that followed Alois Alzheimer’s study of the brain of his patient, Auguste Detter, to the harsh reality of treatment that is still not much different from 100 years ago… … As the father’s illness worsens, the author’s medical exploration to understand the situation his father and his family are facing also deepens.

The symptom that troubled my father the most that winter was short-term memory loss.

I suddenly wondered.

What exactly is memory? How is it encoded in the brain, and why is it so devastated by dementia? These questions were not simply academic ones for me.

As a physician and as a son, I felt compelled to address some of these questions by delving into the science of brain degeneration.

Hopefully, through the process of gaining a deeper understanding of my father's condition, I can gain some insight into the path he is currently on in life and what our family may face in the months and years ahead.

At the same time, I believed that facing my father's amnesia would help us overcome the emotional and practical dilemma we experience when confronted with the altered personality of a loved one.

I decided to explore the issue broadly, from profound questions like what makes us who we are and how we can honor our father's future, as he would have it, to more specific topics like the efficacy of relevant medications and the availability of novel treatments and care options.

(…) If I had to pick the most difficult times for myself during my years as a caregiver, they were when my father's behavior seemed random, inexplicable, and without purpose or blueprint.

Therefore, accumulating scientific and historical knowledge about my father's condition was both a way to understand his needs and a way to take better care of myself. (56-57)

Despite 40 years of research, this disease remains a thorn in the medical community, confusing patients and their caregivers until the very end, even in the dying moments.

Jauhar's three children clash over various issues while caring for their father.

From how to deal with their father, his short-term memory loss and cognitive impairment, to what his true intentions are, issues that seem self-evident from a distance become points of conflict and conflict in the brothers' daily lives.

Personal ethics can often conflict with the realities of caregiving.

A few years ago, the British Alzheimer's Society issued the following statement regarding therapeutic deception (or 'validation therapy'):

“We are skeptical that systematically deceiving people with dementia can build a genuine relationship of trust, allowing them to be heard and their rights to be promoted.” My brother and sister clashed with me frequently on this topic.

The two men, more pragmatic than I, felt that cheating was not a bad idea if it would only relieve my father (and themselves) of some of his grief.

Both were willing to tell their father the stories he wanted to hear.

They both thought that if telling the truth would only anger their father, there was no need to put themselves through such a predicament.

(…)

As mentioned earlier, the amygdala, the area of the human brain that controls emotions, is located just a few millimeters from the hippocampus. Disease in one area can quickly spread to the other.

Therefore, amnesia is often accompanied by emotional outbursts, which are often excessive compared to the event that triggered them.

Lies and deception were easy shortcuts to avoid such critical moments.

Moreover, would such a simple lie be a big deal when the father cannot distinguish between truth and lies and cannot remember what he heard? (193-194)

But I was firmly opposed to it.

I believed that a healthy relationship with my father, even when he was physically and mentally weakened, could only be built on truth and trust.

Little lies, no matter how well-intentioned, would further weaken the already fragile bond between us and our Father. (193-194)

The situation faced by the three siblings, who had to care for their mother, who passed away from Parkinson's disease before her husband, and their father, who began suffering from dementia before his wife and whose condition rapidly worsened after his wife's passing, vividly illustrates the daily reality faced by people living with serious chronic illnesses, including dementia patients and their caregivers.

Physical and mental pain, fatigue, mental stress, career crises, financial difficulties, and fractured lives are not solely personal issues; they reflect social problems and gaps in the healthcare system.

The long messenger conversation between the three siblings from page 197 to page 202

According to the National Dementia Center, the number of dementia patients aged 60 or older in Korea will exceed 1 million as of 2023, accounting for more than 10 percent of the elderly population.

It is predicted that the number will exceed 1.35 million by 2030.

In the United States, where the situation is not much different, perhaps even more serious (there are 6 million Alzheimer's patients in the United States),

This means that one in ten Americans over the age of 65 has the disease.

Moreover, the number is expected to double in 30 years.) The Jauhar brothers, who hire home caregivers and look for private nursing homes to care for their parents, show to some extent the plight of 'middle-of-the-road' patients and their guardians who are left in a blind spot where they cannot even receive health and care services that are perceived as poor by patients and their guardians despite the existence of medical systems such as Medicare and Medicaid and various support programs.

My younger sister often stopped by to wash my mother and change her clothes.

I took care of the medication and packed the groceries.

My brother took care of all the big and small matters of the family.

Even so, the parents' house resembled its two owners and was always in a state of extreme desolation.

That summer of 2014, my brother, sister, and I joined the ranks of some 15 million family caregivers in this country who cared for the elderly without proper compensation (or training).

A 2016 study found that among this largely invisible workforce, the busier half of the population spends an average of about 30 hours a week caring for family members, particularly those with dementia.

Additionally, if you convert the value of the hours they work without pay each year into money, it would be over $400 billion.

There is a price to pay for that.

These family caregivers are not only at a relatively high risk for depression, but are also more likely to experience physical health problems and occupational difficulties, including decreased job productivity.

In America, getting sick and getting old can be scary.

The illness and aging of a loved one can easily lead to my own hard work. (46)

The author naturally turns to foreign examples, such as Hogewijk in the Netherlands, known as the "dementia village," and the "Orange Plan," a long-term care plan for dementia patients in Japan, a country with a large elderly population, and asks how society should address this disease, for which no fundamental treatment has yet been developed.

Opened in 2009, Hogewijk has a reputation for pioneering a highly innovative approach to dementia care.

The nursing home, which was built as a so-called "dementia village," has about 150 residents, most of whom are terminally ill dementia patients requiring 24-hour care. They are allowed to freely roam the various buildings and outdoor spaces within the complex, while being watched closely by cameras and caregivers.

Similar nursing homes have been built in France, Canada, and the United States over the past decade.

(…) According to Leo’s account, the villagers lived in ‘families’ of six or seven people in twenty-three private houses, each with a skilled caregiver.

“We decided that it would be better to form a family.

“Humans naturally want to live that way, with others who have similar interests and ways of thinking.” Leo and his co-founders asked themselves what they would want as caregivers if their mother or father developed dementia and needed long-term care.

The solution they came up with was a home where parents could build friendships with like-minded friends.

“Home is a familiar world,” Leo said.

“It’s different from a memory therapy ward where you have to sit in the same chair for hours on end.” (186)

0

The legacy of relationships

"Someone I Used to Know" is primarily a memoir about a father with Alzheimer's disease, but it also reveals the author's long-standing estrangement from his father, having grown up in a somewhat patriarchal Indian immigrant household.

Everything will be alright, don't worry, I feel good when I see you... ... Only through the occasional words that pop out like that, the humor just enough to relieve the tension, the sincerity that is conveyed when proper expression is no longer possible, can we barely gauge the extent of the affection that the two of them share.

Perhaps widely cited medical sources or lengthy, serious reflections on memory are attempts to bridge that gap in a different, longer and deeper way.

The relationship between the two, which was not directly mentioned until the end of the text, is written at the end of the "Acknowledgments" as follows:

“I would like to express my gratitude to my father, who encouraged and whipped me to navigate life well.

“My father was my first role model as a writer, and as much as I hate to admit it, in good times and bad, in very different ways, I am my father.”

It's heartbreaking and vivid.

(…) An honest piece that touches the heart.

_Minneapolis Star Tribune

Anyone who has ever been a caregiver within a family, or who has ever experienced a loved one's illness, will relate to the Jauhar family's heartfelt and honest journey described in this book.

_『AARP Magazine』

It presents a clear scientific explanation of what happens in our brains as dementia progresses, and depicts in a truly childlike manner the sheer hell it puts those involved in it through.

(…) The scene where the author is confused about what is right while watching his father’s decline resonates deeply.

_The Financial Times

A fascinating mix of medicine and personal history, full of transcendent moments.

_The New York Times

A heartbreaking book that depicts the 'most difficult journey' of witnessing his father Prem Jauhar lose his health, personality, and cognitive abilities to Alzheimer's.

His unflinching honesty about his father's decline and his own inability to fathom it is skillfully complemented by the rigor of medicine.

Any family member who has experienced Alzheimer's will find themselves in this unique work.

_Publisher's Weekly

It's painful, but my heart goes out to you.

(…) A book that is difficult to put down.

_『Kirkus Review』

The way of being and the conclusion of relationships

The original title of this book is My Father's Brain.

From the moment his father was diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease, Sandeep Jauhar embarked on a solo quest to understand his brain and the brains of others with dementia.

He says this book is a journey of that exploration.

Although this is a largely medical expression, this journey ultimately becomes a story about life itself, accumulated as a mental entity, the complexly intertwined human relationships within it, and memory and human existence, as the subject of its exploration is the 'brain'.

It also serves as an example of how one person can continue to be that person (even if he or she cannot be that person to himself or herself) even when things are shaking and collapsing.

This book is (…) about my relationship with my father, especially my relationship with him as he was falling apart from illness in the final stages of his life.

The book is also about the challenges that arise when family members must take on the role of caregiver, the bonds between parents, and the challenges that test those bonds.

The conversations and debates in the book are personal yet profoundly universal.

Perhaps it's a typical example of the conversations and arguments a family might have when confronted with the mental erosion of an adult in the family. But this book goes beyond these personal stories to discuss the brain and memory.

We discuss how and why the brain deteriorates as we age, and explore how we give meaning to our lives even as our memories fade and change with the passage of time.

We also explore how the concept of what it means to be human becomes more complex due to dementia, and the implications this has for patients, their families, and society as a whole (26-27).

While caring for her father, who suffers from dementia, the author witnesses firsthand the loss and confusion he faces in his daily life.

As if responding to his father's gaze that seemed to say, "Don't forget me," he decided to remember him by using his family's history and his own memories.

And in a way I had never thought about before, I re-established my relationship with my father, becoming aware of the obvious and fundamental conditions of human existence, life and death.

“It was a truly dramatic change,” the author says (19).

My father, who was a world-renowned scientist studying wheat genetics in his own laboratory just a few months ago, was diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment. Within a few years, he had lost the ability to remember himself and ultimately, even how to breathe. What happened to him and his family went beyond the painful coping mechanisms of fighting the illness and caring for him.

The 'dramatic change' came not only to my father's brain, but also to my family relationships, and it was a process of managing relationships and managing life much more actively, perhaps even combatively, than I had thought.

As my knowledge grew, I was able to delve deeper into my father's world.

And I was able to bridge a little of the gap between us, a gap that I had tried my whole life to bridge but could never seem to close.

Yet, I think that road was the most difficult one of my life.

For nearly seven years I have been urging and urging, threatening and cajoling, pleading and entreating, encouraging and ridiculing.

I forced my father to go for walks, bought him books and gave him a hug, and forced him to do puzzles.

I loved and cherished my father, but at the same time I hated him.

'Don't forget me,' my father's eyes seemed to say.

Therefore, as a son, I decided to preserve my father's memories as much as possible.

As a result, I learned more about my father, what kind of person he was, what his likes and dislikes, than you did.

Looking back, it was a strange sense of responsibility.

Whenever I went to gatherings, I would always mention that my father had written books and received academic awards.

In that way, I was reminding everyone that your father is bigger than the illness that afflicts him.

(27-28)

Meanwhile, the paradoxical fact that from the moment your father began to lose himself in you, your son's understanding began to develop in a different way and a relationship that had previously been impossible was formed shows that memory is a more complex concept than you might think.

'What is memory, anyway?' This question constantly changes its form throughout the book, functioning as akin to 'Who are we?'

Just as Lenny, the protagonist of the movie "Memento," who suffered from anterograde amnesia, ended up destroying the note that revealed the real culprit who killed his wife, memory can sometimes become the purpose of life itself.

Reflecting on the identity, meaning, and networks of memory, the author uses the essence of memory to reconstruct relationships.

Our memories exist in many places.

Memories live in books, on hard drives, on smartphones, and in other independent entities outside our minds.

Even memories may be shared between more than one brain, such as the brains of several members of a family.

If the primary brain fails to remember, other brains may inevitably take over the task. (97)

As my father was carried out and people began to cry, a strange memory came flooding back to me.

It was a memory from the year after my family came to America.

I was nine years old at the time and was learning to ride a bike on the dusty hillside behind my old Kentucky home.

(…) My father, who I usually remember that day, lost interest as soon as he decided that I could go down the hill by myself and went inside.

But in my memory of that sunny March morning, when I was holding onto my father's lifeless body, for some reason, he was also running beside me.

I pedaled hard down the hill along the rutted path, covered with branches and weeds, with my father keeping pace with me so I wouldn't fall.

I knew that memory was not true, that it could not be true.

But now it has become my memory.

I decided to keep that memory. (340)

He redefines the existence of his father within himself through the concept of memory and the resource of recollection, and redefines the relationship by revising the memories of his childhood that are in some way connected to the time in his later years when he spent the most time with him, caring for him. However, the way this book reveals its virtue is paradoxically the boundary thinking that the author shows.

While he cites the main lines of Western philosophy that view humans as a collection of memories and minds, he points out that “if we define humans solely based on their mental lives, we run the risk of falling into the trap of dehumanization” (245).

How can the integrity of a few neural clusters determine whether a person has a personality, and therefore whether they deserve the rights, moral protections, and respect that come with being human? How can such a crucial characteristic be determined by a mere few brain regions? Incidentally, there is a philosophical perspective that counters this trend.

In short, the psychological 'continuity' that is considered the basis of personality is, however, by no means continuous.

For example, I may not remember something I experienced in my childhood, but I remember something from my youth, and in my youth, I remembered something I experienced in my childhood.

Therefore, if the current me is the same person as the me in my youth, and the me in my youth is the same person as the me in my childhood, then even if there is no psychological continuity, I cannot help but still be the same person as the me in my childhood.

Therefore, of course, memory alone cannot fully determine an individual's identity.

(…) We were still connected by common family ties and a common life story.

Although there were times when my father himself could not remember the family relationships or life story in question.

Nevertheless, he was my father.

Because I thought of Him as my father. (246-247)

A disease 'more frightening than death'

The Shadow of Alzheimer's

If the recollection of one's father is the central theme of "The Person I Used to Know," the discussion of Alzheimer's disease is a side story.

The author, a cardiologist, uses his literary skills, as in “Heart,” to appropriately present a medical narrative on the brain, memory, and Alzheimer’s disease.

From ancient times, when dementia was considered to be a “phantom” or “accumulation of black bile” (Aristotle) or “the result of the coldness of the humors” (Galen), to modern times, when dementia patients were locked up “with ‘the idiots [and] the epileptics and paralytics,’ prostitutes, and various ‘perverts’” and “dunked in cold water or whipped,” to the naming of the disease and the ongoing treatment research that followed Alois Alzheimer’s study of the brain of his patient, Auguste Detter, to the harsh reality of treatment that is still not much different from 100 years ago… … As the father’s illness worsens, the author’s medical exploration to understand the situation his father and his family are facing also deepens.

The symptom that troubled my father the most that winter was short-term memory loss.

I suddenly wondered.

What exactly is memory? How is it encoded in the brain, and why is it so devastated by dementia? These questions were not simply academic ones for me.

As a physician and as a son, I felt compelled to address some of these questions by delving into the science of brain degeneration.

Hopefully, through the process of gaining a deeper understanding of my father's condition, I can gain some insight into the path he is currently on in life and what our family may face in the months and years ahead.

At the same time, I believed that facing my father's amnesia would help us overcome the emotional and practical dilemma we experience when confronted with the altered personality of a loved one.

I decided to explore the issue broadly, from profound questions like what makes us who we are and how we can honor our father's future, as he would have it, to more specific topics like the efficacy of relevant medications and the availability of novel treatments and care options.

(…) If I had to pick the most difficult times for myself during my years as a caregiver, they were when my father's behavior seemed random, inexplicable, and without purpose or blueprint.

Therefore, accumulating scientific and historical knowledge about my father's condition was both a way to understand his needs and a way to take better care of myself. (56-57)

Despite 40 years of research, this disease remains a thorn in the medical community, confusing patients and their caregivers until the very end, even in the dying moments.

Jauhar's three children clash over various issues while caring for their father.

From how to deal with their father, his short-term memory loss and cognitive impairment, to what his true intentions are, issues that seem self-evident from a distance become points of conflict and conflict in the brothers' daily lives.

Personal ethics can often conflict with the realities of caregiving.

A few years ago, the British Alzheimer's Society issued the following statement regarding therapeutic deception (or 'validation therapy'):

“We are skeptical that systematically deceiving people with dementia can build a genuine relationship of trust, allowing them to be heard and their rights to be promoted.” My brother and sister clashed with me frequently on this topic.

The two men, more pragmatic than I, felt that cheating was not a bad idea if it would only relieve my father (and themselves) of some of his grief.

Both were willing to tell their father the stories he wanted to hear.

They both thought that if telling the truth would only anger their father, there was no need to put themselves through such a predicament.

(…)

As mentioned earlier, the amygdala, the area of the human brain that controls emotions, is located just a few millimeters from the hippocampus. Disease in one area can quickly spread to the other.

Therefore, amnesia is often accompanied by emotional outbursts, which are often excessive compared to the event that triggered them.

Lies and deception were easy shortcuts to avoid such critical moments.

Moreover, would such a simple lie be a big deal when the father cannot distinguish between truth and lies and cannot remember what he heard? (193-194)

But I was firmly opposed to it.

I believed that a healthy relationship with my father, even when he was physically and mentally weakened, could only be built on truth and trust.

Little lies, no matter how well-intentioned, would further weaken the already fragile bond between us and our Father. (193-194)

The situation faced by the three siblings, who had to care for their mother, who passed away from Parkinson's disease before her husband, and their father, who began suffering from dementia before his wife and whose condition rapidly worsened after his wife's passing, vividly illustrates the daily reality faced by people living with serious chronic illnesses, including dementia patients and their caregivers.

Physical and mental pain, fatigue, mental stress, career crises, financial difficulties, and fractured lives are not solely personal issues; they reflect social problems and gaps in the healthcare system.

The long messenger conversation between the three siblings from page 197 to page 202

According to the National Dementia Center, the number of dementia patients aged 60 or older in Korea will exceed 1 million as of 2023, accounting for more than 10 percent of the elderly population.

It is predicted that the number will exceed 1.35 million by 2030.

In the United States, where the situation is not much different, perhaps even more serious (there are 6 million Alzheimer's patients in the United States),

This means that one in ten Americans over the age of 65 has the disease.

Moreover, the number is expected to double in 30 years.) The Jauhar brothers, who hire home caregivers and look for private nursing homes to care for their parents, show to some extent the plight of 'middle-of-the-road' patients and their guardians who are left in a blind spot where they cannot even receive health and care services that are perceived as poor by patients and their guardians despite the existence of medical systems such as Medicare and Medicaid and various support programs.

My younger sister often stopped by to wash my mother and change her clothes.

I took care of the medication and packed the groceries.

My brother took care of all the big and small matters of the family.

Even so, the parents' house resembled its two owners and was always in a state of extreme desolation.

That summer of 2014, my brother, sister, and I joined the ranks of some 15 million family caregivers in this country who cared for the elderly without proper compensation (or training).

A 2016 study found that among this largely invisible workforce, the busier half of the population spends an average of about 30 hours a week caring for family members, particularly those with dementia.

Additionally, if you convert the value of the hours they work without pay each year into money, it would be over $400 billion.

There is a price to pay for that.

These family caregivers are not only at a relatively high risk for depression, but are also more likely to experience physical health problems and occupational difficulties, including decreased job productivity.

In America, getting sick and getting old can be scary.

The illness and aging of a loved one can easily lead to my own hard work. (46)

The author naturally turns to foreign examples, such as Hogewijk in the Netherlands, known as the "dementia village," and the "Orange Plan," a long-term care plan for dementia patients in Japan, a country with a large elderly population, and asks how society should address this disease, for which no fundamental treatment has yet been developed.

Opened in 2009, Hogewijk has a reputation for pioneering a highly innovative approach to dementia care.

The nursing home, which was built as a so-called "dementia village," has about 150 residents, most of whom are terminally ill dementia patients requiring 24-hour care. They are allowed to freely roam the various buildings and outdoor spaces within the complex, while being watched closely by cameras and caregivers.

Similar nursing homes have been built in France, Canada, and the United States over the past decade.

(…) According to Leo’s account, the villagers lived in ‘families’ of six or seven people in twenty-three private houses, each with a skilled caregiver.

“We decided that it would be better to form a family.

“Humans naturally want to live that way, with others who have similar interests and ways of thinking.” Leo and his co-founders asked themselves what they would want as caregivers if their mother or father developed dementia and needed long-term care.

The solution they came up with was a home where parents could build friendships with like-minded friends.

“Home is a familiar world,” Leo said.

“It’s different from a memory therapy ward where you have to sit in the same chair for hours on end.” (186)

0

The legacy of relationships

"Someone I Used to Know" is primarily a memoir about a father with Alzheimer's disease, but it also reveals the author's long-standing estrangement from his father, having grown up in a somewhat patriarchal Indian immigrant household.

Everything will be alright, don't worry, I feel good when I see you... ... Only through the occasional words that pop out like that, the humor just enough to relieve the tension, the sincerity that is conveyed when proper expression is no longer possible, can we barely gauge the extent of the affection that the two of them share.

Perhaps widely cited medical sources or lengthy, serious reflections on memory are attempts to bridge that gap in a different, longer and deeper way.

The relationship between the two, which was not directly mentioned until the end of the text, is written at the end of the "Acknowledgments" as follows:

“I would like to express my gratitude to my father, who encouraged and whipped me to navigate life well.

“My father was my first role model as a writer, and as much as I hate to admit it, in good times and bad, in very different ways, I am my father.”

It's heartbreaking and vivid.

(…) An honest piece that touches the heart.

_Minneapolis Star Tribune

Anyone who has ever been a caregiver within a family, or who has ever experienced a loved one's illness, will relate to the Jauhar family's heartfelt and honest journey described in this book.

_『AARP Magazine』

It presents a clear scientific explanation of what happens in our brains as dementia progresses, and depicts in a truly childlike manner the sheer hell it puts those involved in it through.

(…) The scene where the author is confused about what is right while watching his father’s decline resonates deeply.

_The Financial Times

A fascinating mix of medicine and personal history, full of transcendent moments.

_The New York Times

A heartbreaking book that depicts the 'most difficult journey' of witnessing his father Prem Jauhar lose his health, personality, and cognitive abilities to Alzheimer's.

His unflinching honesty about his father's decline and his own inability to fathom it is skillfully complemented by the rigor of medicine.

Any family member who has experienced Alzheimer's will find themselves in this unique work.

_Publisher's Weekly

It's painful, but my heart goes out to you.

(…) A book that is difficult to put down.

_『Kirkus Review』

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: August 21, 2024

- Page count, weight, size: 348 pages | 130*200*20mm

- ISBN13: 9791169092890

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)