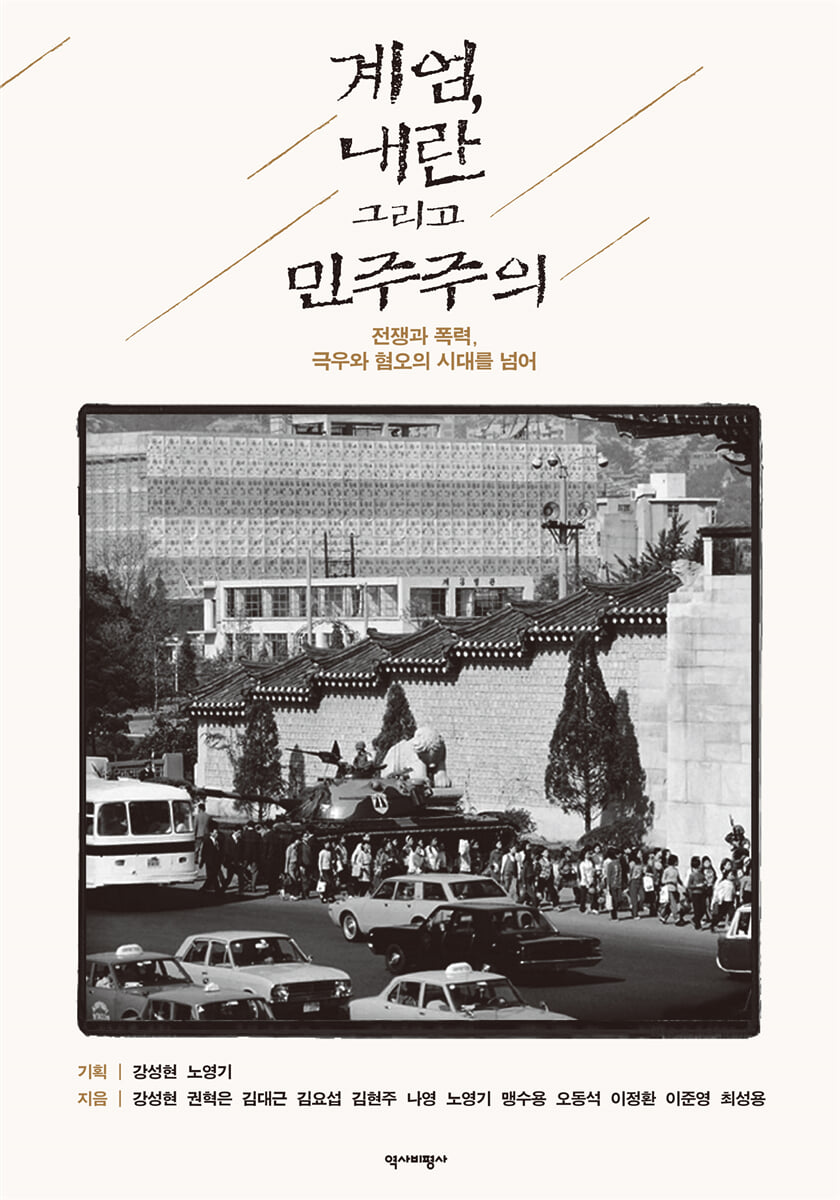

Martial law, civil war, and democracy

|

Description

Book Introduction

The authors of this book sought to create a knowledge commons, not as I but as we, following Yoon Seok-yeol's December 3 coup, and to address the history of martial law in Korea, the law and literature of the state of exception, and the experiences and education of citizens in the face of civil war.

As a historian, legal scholar, socio-cultural scholar, teacher, literary critic, journalist, and activist, I have looked back on martial law and the civil war from various angles and reflected on democracy.

“Martial law does not only mean a physical situation in which the military takes control of the streets and squares.

It is a governing technique that legalizes violence and temporarily suspends democracy through exception clauses in the Constitution.

The declaration of martial law on December 3, 2024, demonstrates the repetition of these ruling techniques.

This incident was not a legacy of a past military regime, but the latest iteration of a ruling structure that still operates at the levels of constitution, institutions, emotions, and technology.

Martial law always appears under the pretext of an 'emergency,' but in reality it is a self-replicating system that justifies itself by manipulating or inducing the 'emergency' itself.

Therefore, when discussing the crisis of democracy today, martial law is not simply a historical event, but a theoretical concept that should be at the center of analysis.”

―「Preface to a New Democracy」, p. 11.

As a historian, legal scholar, socio-cultural scholar, teacher, literary critic, journalist, and activist, I have looked back on martial law and the civil war from various angles and reflected on democracy.

“Martial law does not only mean a physical situation in which the military takes control of the streets and squares.

It is a governing technique that legalizes violence and temporarily suspends democracy through exception clauses in the Constitution.

The declaration of martial law on December 3, 2024, demonstrates the repetition of these ruling techniques.

This incident was not a legacy of a past military regime, but the latest iteration of a ruling structure that still operates at the levels of constitution, institutions, emotions, and technology.

Martial law always appears under the pretext of an 'emergency,' but in reality it is a self-replicating system that justifies itself by manipulating or inducing the 'emergency' itself.

Therefore, when discussing the crisis of democracy today, martial law is not simply a historical event, but a theoretical concept that should be at the center of analysis.”

―「Preface to a New Democracy」, p. 11.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Preface to a New Democracy: Beyond Repeated Martial Law and Civil War

Part 1: The History of Martial Law in Korea

Chapter 1: The Birth of Korean Martial Law: The Yeosu-Suncheon Incident, the Jeju April 3 Incident, and Martial Law During the Korean War

1.

Revisiting Martial Law: The Failure of the December 3 Coup and the History of Martial Law in Korea

2.

Martial law without martial law - the declaration of martial law and the experience of the Yeosu-Suncheon Incident and the Jeju April 3 Incident

3.

The Birth of "Creative Violence"—The Contents and Issues of the Martial Law Enactment Process

4.

The Routine and Normalization of the State of Exception: The Declaration of Martial Law and the State of Martial Law at the Beginning of the Korean War

5.

The Specter of Martial Law and the Challenges of Democracy

Chapter 2: The Prelude to 32 Years of Military Dictatorship - The May 16 Military Coup and Martial Law

1.

Martial law, a tool for coup forces to seize power

2.

Anti-communism and the eradication of "communist elements": Resistance blocked

3.

Restrictions on political power and reorganization of political forces

4.

Exercise of arbitrary legislative power

5.

Deferred resistance

Chapter 3: Organization of Resistance, Systematization of Martial Law - The June 3rd Uprising and Martial Law

1.

The first organized and sustained democratization movement

2.

Creating new forms of resistance

3.

The incident where airborne troops stormed the Seoul District Court

4.

Declaring martial law when cornered

5.

Military mobilization and American support

6.

Advanced violence

7.

Justifying the Requirements for Declaring Martial Law through Legal Technology

8.

Systematic martial law

Chapter 4: The Era of Emergency Powers and Emergency Measures: The Yushin Coup and the October 17 Martial Law

1.

Prelude to the Yushin era

2.

Background of the Yushin Coup

3.

October 17 Martial Law and the President's Special Declaration

4.

Promulgation of the Yushin Constitution and the emergency measures of Article 53

5.

The anti-Yushin democratization struggle of the 'Ginjo era'

6.

The Yushin Coup Stands in the Court of History

Chapter 5: Collapsed Democracy, Revived Military Dictatorship—The Buma Uprising, the December 12 Military Coup, and the May 18 Uprising

1.

The civil war that led to the uprising

2.

The Buma Uprising and the Fall of the Yushin Dictatorship

3.

The beginning of the May 18th Uprising

4.

The scars left by martial law

Part II: The Nature of Law and the Human Condition

Chapter 6: Why Martial Law Became a Tool for State Crime

1.

The problem raised by the December 3 martial law

2.

Constitutional national emergency power

3.

Types of national emergency powers

4.

The first martial law and the unconstitutionality of the enacted 'Martial Law'

5.

The significance of martial law as a tool in the December 3rd Rebellion

6.

The Constitutional Lessons of the December 3rd Martial Law

7.

Legislative Tasks for Overcoming the December 3 Rebellion

〈Appendix〉 Comparison of Japanese Martial Law and the Martial Law Enacted in 1949

Chapter 7: Thinking Law Outside the Law: The Possibility and Practice of the Right to Resistance

1.

Martial law and resistance! Resistance?

2.

State of exception and national emergency powers

3.

The concept and properties of the right to resist

4.

Understanding the Right to Resistance in Our Legal Reality

5.

The right to resist as a practice that allows one to think about law outside the law

Chapter 8: Standing Before the Flashlight - Korean Literature and the Memory of Martial Law

1.

The never-ending night

2.

Memories of martial law without martial law

3.

asked who i was

4.

Again, standing in front of the flashlight

Part 3: Memories of Civil War and a New Path to Democracy

Chapter 9: Algorithmic Civil War: The End of a President Fueled by Far-Right YouTube

1.

No power has ever succeeded by trampling on the press.

2.

Yoon Seok-yeol's brain-rotten politics and the dysfunction of the public sphere.

3.

The lesson of history: the truth will eventually emerge.

Chapter 10: A Movement for a New Society—From the Square to the Field, Cracks for Change

1.

The 'brave and revolutionary' people who took to the square

2.

The first crack: opening an 'equal and democratic' square

3.

The second crack demands the content of a 'different democracy'

4.

Third crack, organizing the movement from the square to the scene

5.

Democracy, the subject of resistance, and the qualifications of the 'citizen'

6.

For a democracy that connects the 'dead' to the present.

7.

To begin the transition to a different society beyond the protection of the constitutional order

Chapter 11: From the Long Night of Civil War to the Post-Civil War World: 123 Days of Civil War as Seen Through the Development of Language

1.

Looking back on the 123 days of civil war

2.

Words that flowed on the night of civil war

3.

Rampant denialism and civil war of language

4.

Remember the square

Chapter 12: Classes after the December 3rd Martial Law and Records of Conversations

1.

After martial law, questions began in the classroom.

2.

History Class, Facing the Present

3.

How should I communicate with students with diverse perspectives?

4.

Creating a 'narrative' for the future

5.

The meaning and questions left by the records of the conversation

Americas / References / List of Martial Laws / Authors of this book

Part 1: The History of Martial Law in Korea

Chapter 1: The Birth of Korean Martial Law: The Yeosu-Suncheon Incident, the Jeju April 3 Incident, and Martial Law During the Korean War

1.

Revisiting Martial Law: The Failure of the December 3 Coup and the History of Martial Law in Korea

2.

Martial law without martial law - the declaration of martial law and the experience of the Yeosu-Suncheon Incident and the Jeju April 3 Incident

3.

The Birth of "Creative Violence"—The Contents and Issues of the Martial Law Enactment Process

4.

The Routine and Normalization of the State of Exception: The Declaration of Martial Law and the State of Martial Law at the Beginning of the Korean War

5.

The Specter of Martial Law and the Challenges of Democracy

Chapter 2: The Prelude to 32 Years of Military Dictatorship - The May 16 Military Coup and Martial Law

1.

Martial law, a tool for coup forces to seize power

2.

Anti-communism and the eradication of "communist elements": Resistance blocked

3.

Restrictions on political power and reorganization of political forces

4.

Exercise of arbitrary legislative power

5.

Deferred resistance

Chapter 3: Organization of Resistance, Systematization of Martial Law - The June 3rd Uprising and Martial Law

1.

The first organized and sustained democratization movement

2.

Creating new forms of resistance

3.

The incident where airborne troops stormed the Seoul District Court

4.

Declaring martial law when cornered

5.

Military mobilization and American support

6.

Advanced violence

7.

Justifying the Requirements for Declaring Martial Law through Legal Technology

8.

Systematic martial law

Chapter 4: The Era of Emergency Powers and Emergency Measures: The Yushin Coup and the October 17 Martial Law

1.

Prelude to the Yushin era

2.

Background of the Yushin Coup

3.

October 17 Martial Law and the President's Special Declaration

4.

Promulgation of the Yushin Constitution and the emergency measures of Article 53

5.

The anti-Yushin democratization struggle of the 'Ginjo era'

6.

The Yushin Coup Stands in the Court of History

Chapter 5: Collapsed Democracy, Revived Military Dictatorship—The Buma Uprising, the December 12 Military Coup, and the May 18 Uprising

1.

The civil war that led to the uprising

2.

The Buma Uprising and the Fall of the Yushin Dictatorship

3.

The beginning of the May 18th Uprising

4.

The scars left by martial law

Part II: The Nature of Law and the Human Condition

Chapter 6: Why Martial Law Became a Tool for State Crime

1.

The problem raised by the December 3 martial law

2.

Constitutional national emergency power

3.

Types of national emergency powers

4.

The first martial law and the unconstitutionality of the enacted 'Martial Law'

5.

The significance of martial law as a tool in the December 3rd Rebellion

6.

The Constitutional Lessons of the December 3rd Martial Law

7.

Legislative Tasks for Overcoming the December 3 Rebellion

〈Appendix〉 Comparison of Japanese Martial Law and the Martial Law Enacted in 1949

Chapter 7: Thinking Law Outside the Law: The Possibility and Practice of the Right to Resistance

1.

Martial law and resistance! Resistance?

2.

State of exception and national emergency powers

3.

The concept and properties of the right to resist

4.

Understanding the Right to Resistance in Our Legal Reality

5.

The right to resist as a practice that allows one to think about law outside the law

Chapter 8: Standing Before the Flashlight - Korean Literature and the Memory of Martial Law

1.

The never-ending night

2.

Memories of martial law without martial law

3.

asked who i was

4.

Again, standing in front of the flashlight

Part 3: Memories of Civil War and a New Path to Democracy

Chapter 9: Algorithmic Civil War: The End of a President Fueled by Far-Right YouTube

1.

No power has ever succeeded by trampling on the press.

2.

Yoon Seok-yeol's brain-rotten politics and the dysfunction of the public sphere.

3.

The lesson of history: the truth will eventually emerge.

Chapter 10: A Movement for a New Society—From the Square to the Field, Cracks for Change

1.

The 'brave and revolutionary' people who took to the square

2.

The first crack: opening an 'equal and democratic' square

3.

The second crack demands the content of a 'different democracy'

4.

Third crack, organizing the movement from the square to the scene

5.

Democracy, the subject of resistance, and the qualifications of the 'citizen'

6.

For a democracy that connects the 'dead' to the present.

7.

To begin the transition to a different society beyond the protection of the constitutional order

Chapter 11: From the Long Night of Civil War to the Post-Civil War World: 123 Days of Civil War as Seen Through the Development of Language

1.

Looking back on the 123 days of civil war

2.

Words that flowed on the night of civil war

3.

Rampant denialism and civil war of language

4.

Remember the square

Chapter 12: Classes after the December 3rd Martial Law and Records of Conversations

1.

After martial law, questions began in the classroom.

2.

History Class, Facing the Present

3.

How should I communicate with students with diverse perspectives?

4.

Creating a 'narrative' for the future

5.

The meaning and questions left by the records of the conversation

Americas / References / List of Martial Laws / Authors of this book

Publisher's Review

December 3, 2024: Martial law declared for the first time in 45 years

How martial law has been repeated and transformed in modern Korean history.

In South Korea, teenagers and young adults born after 1981 did not experience martial law, while middle-aged and elderly people born before 1980 trembled under martial law.

Martial law, which was said to have occurred in the last century, something that could only be found in history textbooks, has now faded into obscurity, making it difficult to remember when and why it occurred. However, in December 2024 of the 21st century, it became a reality.

The shock was even greater because, since 1987, a democratic constitutional order had gradually taken hold, and the situation could not be recognized as a national emergency.

It was the first martial law in 45 years (as of October 27, 1979, with martial law expanded nationwide on May 17, 1980) and the 17th martial law.

In South Korea, martial law was abused as a ruling technique by past dictatorships.

Part 1 of this book examines the history of martial law, which was used as a governing technique to temporarily suspend democracy during the regimes of Syngman Rhee, Park Chung-hee, and Chun Doo-hwan.

The first martial law declared by the South Korean government was on October 22, 1948, during the Syngman Rhee administration, by the commander of the Yeosu-Suncheon military camp, who was not even the president, without any formal procedures and without a martial law.

Martial law was also declared during the Jeju April 3 Incident and the Korean War. This paper examines the process by which martial law was institutionalized under the name of "martial law," which was not a law responding to an emergency situation, but violence prior to the law.

Park Chung-hee took power through the May 16 military coup in 1961 and destroyed the constitutional order through martial law under the guise of “restoring order.”

It was the beginning of a 32-year military dictatorship.

The military government's martial law rule became the prototype for all subsequent coups.

During the Park Chung-hee regime, martial law and a state of emergency were declared to suppress protests against the Korea-Japan Agreement in 1964, and martial law was declared in 1972, paving the way for a coup d'état and the Yushin regime.

The Yushin Constitution institutionalized the president's emergency powers and was a decisive turning point that brought martial law within the Constitution rather than outside it.

The ruler arbitrarily exercised emergency powers, breaking the law and the principle of separation of powers.

The period of 1979-1980 was a period when martial law continued, the 12/12 military coup led by Chun Doo-hwan and the Hanahoe took place, and the May 18th Uprising was suppressed with state violence.

The new military junta trampled on civil resistance and used martial law as a tool to seize power.

The memory of Gwangju continued as a civil resistance to suppress martial law in 2024.

How was martial law possible?

The institutional nature of martial law, and resistance and oppression as reflected in law and literature.

A state in which the ruling power suspends the law and exercises authority that transcends itself is called a 'state of exception'.

Also, in situations where the constitutional order is threatened, the special powers that the ruler temporarily exercises beyond the law and the principle of separation of powers are called 'emergency powers.'

The martial law that was repeatedly declared in Korea was because this state of exception had a structure institutionalized in the Constitution and laws, and because the president artificially created a state of emergency and exercised national emergency powers and emergency powers, institutionalizing dictatorial powers.

In particular, Yoon Seok-yeol's December 3 martial law was illegal in itself by deceiving people into thinking it was a state of exception when it was not from the beginning.

Part 2 of this book closely analyzes the constitution and the structure of state power that made the state of exception possible, and further examines how martial law has been remembered and recorded in Korean literature.

South Korea is vulnerable to internal strife among those in power.

This is the biggest problem with the constitutional system of the Republic of Korea.

Furthermore, the current martial law was enacted by uncritically accepting and almost copying the martial law of the Japanese Empire, and although it has been revised several times, it has not been able to completely escape from it, and has created an unconstitutional state that alienates and rejects the norms of the Constitution of the Republic of Korea.

The Constitution of the Republic of Korea has many problems, including a provision that recognizes the jurisdiction of military courts over civilians when martial law is declared (Article 27, Paragraph 2) and a human rights-violating provision that grants the military the authority to infringe on basic rights (Article 77, Paragraph 3).

Moreover, the Constitution recognizes the President's national emergency power as an exception to the separation of powers, allowing state crimes such as internal rebellion to operate within the legal framework.

In Korean constitutional history, martial law was not a means of preserving the Constitution, but rather a means of destroying it.

This is because the imperial presidency lacked or lacked laws that could tightly control the president, including the power to declare martial law.

The resistance of citizens who rushed to the National Assembly on December 3rd and blocked the tanks amidst a state of exception outside the law, which suspended the effect of the law, can be said to be an exercise of popular sovereignty to restore a democratic country governed by the rule of law and protect the constitutional order, and an act of self-defense against illegal public power.

The right to resist is law as a practical institution that allows one to think about law outside the law.

Martial law, which was used as a means to justify the reorganization of unjust power and state violence and crime, tells us in Korean literature that it was not a memory of the past, but a structure of oppression that has continued to the present.

Ironically, in Korean literature, the memory of martial law has been recorded in a way that does not speak about martial law.

This is because, even after martial law was lifted during the repeated martial law, it continued to dominate daily life and darkness continued as an endless night.

Citizens are the main actors

A new democracy opening up in the media, public squares, on-site, and classrooms

Yoon Seok-yeol's December 3 coup and internal strife are not just political and legal issues.

The algorithmic rebellion of far-right YouTubers, the language of rebellion filled with hostility and hatred, and the false propaganda that has infiltrated even school classrooms through social media are also issues that must be examined.

This remains a serious problem even after martial law has ended and Yoon Seok-yeol is on criminal trial.

Part 3 of this book explores how language, emotion, memory, and practice can reconstruct democracy in the post-martial law era.

This article, which examines the president's deafness to media criticism and his obsession with YouTube's algorithm, and the distorted structure of the journalism ecosystem, highlights the urgency and necessity of media reform and the restoration of public opinion.

Meanwhile, the process by which the citizens' resistance that erupted on the streets after the December 3 martial law led to various social movements shows that the "crack" for change is not a disconnection but a strategy for connection and a starting point for opening up a new political sensibility.

The political turmoil over language following the impeachment of Yoon Seok-yeol has not yet ended.

This is because the strategy of glorifying martial law and the discourse of denial of the civil war still continue.

Although the negative effects of this can affect students, the history lessons and conversations that take place in the classroom show the potential of democratic education.

How martial law has been repeated and transformed in modern Korean history.

In South Korea, teenagers and young adults born after 1981 did not experience martial law, while middle-aged and elderly people born before 1980 trembled under martial law.

Martial law, which was said to have occurred in the last century, something that could only be found in history textbooks, has now faded into obscurity, making it difficult to remember when and why it occurred. However, in December 2024 of the 21st century, it became a reality.

The shock was even greater because, since 1987, a democratic constitutional order had gradually taken hold, and the situation could not be recognized as a national emergency.

It was the first martial law in 45 years (as of October 27, 1979, with martial law expanded nationwide on May 17, 1980) and the 17th martial law.

In South Korea, martial law was abused as a ruling technique by past dictatorships.

Part 1 of this book examines the history of martial law, which was used as a governing technique to temporarily suspend democracy during the regimes of Syngman Rhee, Park Chung-hee, and Chun Doo-hwan.

The first martial law declared by the South Korean government was on October 22, 1948, during the Syngman Rhee administration, by the commander of the Yeosu-Suncheon military camp, who was not even the president, without any formal procedures and without a martial law.

Martial law was also declared during the Jeju April 3 Incident and the Korean War. This paper examines the process by which martial law was institutionalized under the name of "martial law," which was not a law responding to an emergency situation, but violence prior to the law.

Park Chung-hee took power through the May 16 military coup in 1961 and destroyed the constitutional order through martial law under the guise of “restoring order.”

It was the beginning of a 32-year military dictatorship.

The military government's martial law rule became the prototype for all subsequent coups.

During the Park Chung-hee regime, martial law and a state of emergency were declared to suppress protests against the Korea-Japan Agreement in 1964, and martial law was declared in 1972, paving the way for a coup d'état and the Yushin regime.

The Yushin Constitution institutionalized the president's emergency powers and was a decisive turning point that brought martial law within the Constitution rather than outside it.

The ruler arbitrarily exercised emergency powers, breaking the law and the principle of separation of powers.

The period of 1979-1980 was a period when martial law continued, the 12/12 military coup led by Chun Doo-hwan and the Hanahoe took place, and the May 18th Uprising was suppressed with state violence.

The new military junta trampled on civil resistance and used martial law as a tool to seize power.

The memory of Gwangju continued as a civil resistance to suppress martial law in 2024.

How was martial law possible?

The institutional nature of martial law, and resistance and oppression as reflected in law and literature.

A state in which the ruling power suspends the law and exercises authority that transcends itself is called a 'state of exception'.

Also, in situations where the constitutional order is threatened, the special powers that the ruler temporarily exercises beyond the law and the principle of separation of powers are called 'emergency powers.'

The martial law that was repeatedly declared in Korea was because this state of exception had a structure institutionalized in the Constitution and laws, and because the president artificially created a state of emergency and exercised national emergency powers and emergency powers, institutionalizing dictatorial powers.

In particular, Yoon Seok-yeol's December 3 martial law was illegal in itself by deceiving people into thinking it was a state of exception when it was not from the beginning.

Part 2 of this book closely analyzes the constitution and the structure of state power that made the state of exception possible, and further examines how martial law has been remembered and recorded in Korean literature.

South Korea is vulnerable to internal strife among those in power.

This is the biggest problem with the constitutional system of the Republic of Korea.

Furthermore, the current martial law was enacted by uncritically accepting and almost copying the martial law of the Japanese Empire, and although it has been revised several times, it has not been able to completely escape from it, and has created an unconstitutional state that alienates and rejects the norms of the Constitution of the Republic of Korea.

The Constitution of the Republic of Korea has many problems, including a provision that recognizes the jurisdiction of military courts over civilians when martial law is declared (Article 27, Paragraph 2) and a human rights-violating provision that grants the military the authority to infringe on basic rights (Article 77, Paragraph 3).

Moreover, the Constitution recognizes the President's national emergency power as an exception to the separation of powers, allowing state crimes such as internal rebellion to operate within the legal framework.

In Korean constitutional history, martial law was not a means of preserving the Constitution, but rather a means of destroying it.

This is because the imperial presidency lacked or lacked laws that could tightly control the president, including the power to declare martial law.

The resistance of citizens who rushed to the National Assembly on December 3rd and blocked the tanks amidst a state of exception outside the law, which suspended the effect of the law, can be said to be an exercise of popular sovereignty to restore a democratic country governed by the rule of law and protect the constitutional order, and an act of self-defense against illegal public power.

The right to resist is law as a practical institution that allows one to think about law outside the law.

Martial law, which was used as a means to justify the reorganization of unjust power and state violence and crime, tells us in Korean literature that it was not a memory of the past, but a structure of oppression that has continued to the present.

Ironically, in Korean literature, the memory of martial law has been recorded in a way that does not speak about martial law.

This is because, even after martial law was lifted during the repeated martial law, it continued to dominate daily life and darkness continued as an endless night.

Citizens are the main actors

A new democracy opening up in the media, public squares, on-site, and classrooms

Yoon Seok-yeol's December 3 coup and internal strife are not just political and legal issues.

The algorithmic rebellion of far-right YouTubers, the language of rebellion filled with hostility and hatred, and the false propaganda that has infiltrated even school classrooms through social media are also issues that must be examined.

This remains a serious problem even after martial law has ended and Yoon Seok-yeol is on criminal trial.

Part 3 of this book explores how language, emotion, memory, and practice can reconstruct democracy in the post-martial law era.

This article, which examines the president's deafness to media criticism and his obsession with YouTube's algorithm, and the distorted structure of the journalism ecosystem, highlights the urgency and necessity of media reform and the restoration of public opinion.

Meanwhile, the process by which the citizens' resistance that erupted on the streets after the December 3 martial law led to various social movements shows that the "crack" for change is not a disconnection but a strategy for connection and a starting point for opening up a new political sensibility.

The political turmoil over language following the impeachment of Yoon Seok-yeol has not yet ended.

This is because the strategy of glorifying martial law and the discourse of denial of the civil war still continue.

Although the negative effects of this can affect students, the history lessons and conversations that take place in the classroom show the potential of democratic education.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: August 20, 2025

- Page count, weight, size: 440 pages | 520g | 152*224*22mm

- ISBN13: 9788976966032

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)