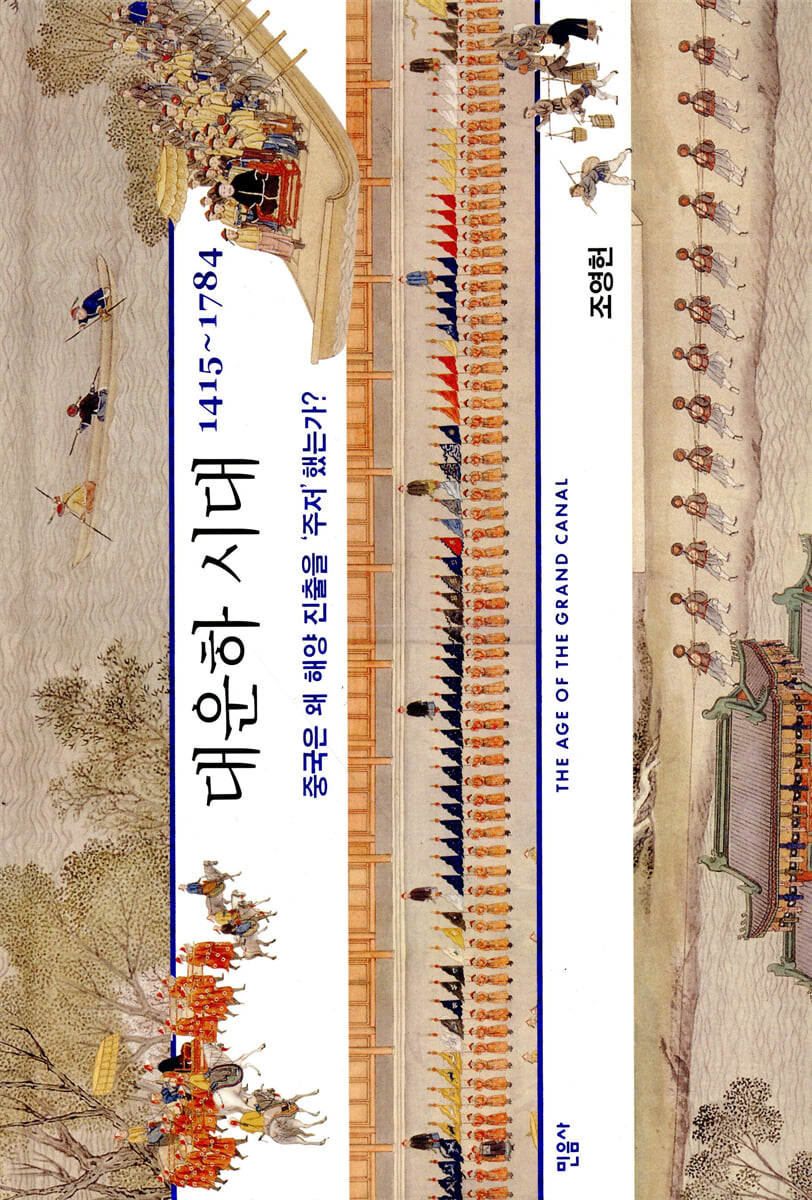

Grand Canal Era 1415–1784

|

Description

Book Introduction

If there was an age of exploration in Europe

China has its Grand Canal era.

Professor Cho Young-heon, who presented a new paradigm for the study of modern Chinese history with his book “The Grand Canal and Chinese Merchants,” presents his first book in 10 years.

This book captures China's 'Ming and Qing Dynasties' with the groundbreaking concept of the 'Grand Canal Era'.

China, once the world's wealthiest and most powerful empire, prospered from the 15th to the 18th centuries by transporting goods, people, and information through the Grand Canal, which stretched for approximately 1,800 kilometers.

However, the era of the Grand Canal was also a paradoxical one, as it further strengthened China's "sea phobia" and brought about the decline of the empire.

Through vivid episodes featuring a variety of characters, including emperors, officials, merchants, pirates, and missionaries, the author elevates the era of the Grand Canal to a time in world history comparable to the Age of Exploration.

China has its Grand Canal era.

Professor Cho Young-heon, who presented a new paradigm for the study of modern Chinese history with his book “The Grand Canal and Chinese Merchants,” presents his first book in 10 years.

This book captures China's 'Ming and Qing Dynasties' with the groundbreaking concept of the 'Grand Canal Era'.

China, once the world's wealthiest and most powerful empire, prospered from the 15th to the 18th centuries by transporting goods, people, and information through the Grand Canal, which stretched for approximately 1,800 kilometers.

However, the era of the Grand Canal was also a paradoxical one, as it further strengthened China's "sea phobia" and brought about the decline of the empire.

Through vivid episodes featuring a variety of characters, including emperors, officials, merchants, pirates, and missionaries, the author elevates the era of the Grand Canal to a time in world history comparable to the Age of Exploration.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Recommendation

Opening Remarks: China's "Sea Power" and the "Grand Canal Era"

Was Zheng He a pioneer of maritime China? / A comparison with the 'Age of Exploration' / Was it due to 'European success'? / While simultaneously wary of Eurocentrism and Sinocentrism / How should we understand China's practices that are neither 'sea ban' nor 'open sea ban'? / An era when the Grand Canal enabled us to gauge domestic and foreign logistics trends / Two characteristics of the Grand Canal era in a narrow sense / The structure and narrative style of this book

Chapter 1: 1415: Emperor Yongle prepares to move the capital to Beijing and rebuilds the Grand Canal.

The opening of the Cheonggangpo Port and the 'Paid Shipping' / Paid Shipping / The Giraffe Brought by the Zheng He Expedition / The Dark Shadow of Coup and Massacre / The Move of the Capital to Beijing / The Touchstone of the Success of the Move of the Capital to Beijing: The Reconstruction of the Grand Canal / The Move of the Capital to Beijing and Kublai Khan / Why Did the Yongle Emperor Ban Shipping? / The Significance of the Unification of Shipping through the Grand Canal / The Dispatch of Zheng He and the Increase in Tributary States / Why Did China Hesitate to the Sea After Zheng He? / The Portuguese Occupation of Ceuta in 1415

Chapter 2: 1492: A Huizhou merchant seizes a new opportunity with a change in the salt-cloud law.

1492, the implementation of the Yunsa Nap-eun system by the Qing Dynasty / The salt distribution law of the Ming Dynasty linked to the supply of military supplies to the northern border / 1449, the 'land empire' through the Tomokbo Incident / The first beneficiaries of the Kaizhong Law, Shanxi and Shaanxi merchants / Yangzhou, the central city of the Huaiyang region / The Yunsa Nap-eun system, a golden opportunity for Huizhou merchants / The overseas expansion of Huizhou merchants and the expansion of the Yin economy / The dispatch of the eunuch Luo Bao and the change in the landscape of Yan Shanggui / The choices of Huizhou merchants / Was there no other option? / Implications of Wang Zhi, a Huizhou merchant and maritime expert / Thinking back to 1492

Chapter 3: 1573: Governor-General Wang Jong-mok attempts to transport goods by sea.

1573: A transport ship capsizes at sea / Critical opinions on shipping / Three solutions to appease Beijing's people / The political variable of Zhang Juzheng / 'Pahaeun': Shipping halted again / The world-historical significance of the 1573 shipping 'death'

Chapter 4: 1600: Jesuit missionary Matteo Ricci evaluates the Grand Canal

1600, Matteo Ricci and Xu Guangqi's first meeting / Why was Ricci in Nanjing in 1600? / Ricci, who traveled to and from Beijing using the Grand Canal / Ships carrying foreign tributes / Ricci, who discovered the 'illegal' operation of tribute ships / Matteo Ricci's difficult problem / The truth about the fear of the sea: (1) Japanese pirates / The truth about the fear of the sea: (2) The Imjin War / The truth about the fear of the sea: (3) European armed forces / Xu Guangqi's perception of the frontier / Chinese maritime maps drawn around 1608 / The world historical significance of 1600

Chapter 5: 1666: Salt merchant Jeong Yu-yong rebuilds Cheonbigung Palace.

1666, the relocation and construction of the Yangju Cheonbigung / Jeong Yu-yong's story of rebuilding the Cheonbigung / the formation and spread of the Mazu faith / the change from the sea god to the god of the sea / the restoration of the function of the Yangju Cheonbigung through a change in location / the Grand Canal pile removal project / Jeong Yu-yong's gambit / Adam Schall's death and Yang Gwang-seon's attack / 1666, the 'Year of Wonders'

Chapter 6: 1684: Emperor Kangxi begins his tour of the Jiangnan region using the Grand Canal.

1684, Kangxi Emperor's first tour of the southern part of the Yangtze River / The purpose of the southern tour / A clever plan to simultaneously resolve both the supply of goods and transportation / The establishment of four customs offices / The genealogy of the Zheng clan's maritime power / The side effects of the Tianqi Ling / A new source of vitality for maritime trade / A 'compromise' between security and profit / The significance of the Grand Canal, the emperor's route for southern tours

Chapter 7: 1757: Emperor Qianlong reduces the number of customs offices for Western ships after his Southern Tour.

The identity of the British ships appearing in Ningbo / Concerns about becoming a second Macau / The Qianlong Emperor's second southern tour and its background / The collusion between the Qianlong Emperor and the Yanxiang of Yangzhou / The reduction of the sea gateway from four to one in 1757 / The Qianlong Emperor's fears? / The reality of the concerns and fears (1): Increasing overseas migration and collusion with 'subversive' Western powers / The reality of the concerns and fears (2): The spread of Christianity in the mainland and the expanding Christian network / Why Gwangju? / Maritime policy linked to the northwestern border policy

Chapter 8: 1784: Emperor Qianlong completes his final tour of the Jiangnan region using the Grand Canal.

1784, Emperor Qianlong's sixth southern tour / The regrets of Yangzhou merchants about his last southern tour / The Gwangju Jiaoan Incident of 1784 / Emperor Qianlong's anxiety over the possibility of connections between Westerners and Muslims / The beginning of US-China trade and the 'American impact' / The aftermath of the Lady Hughes incident / The end of the Grand Canal era, 1784

Concluding Remarks: The End of the 'Grand Canal Era' and What Happened Afterward

Why I hesitated to use the word "hesitant"? / Lack of motivation to advance into the sea? / Threat from northern peoples? / Deficiency and threat theories seen through the Grand Canal, an icon of inter-Korean unification / "Fear" and "controlled openness" regarding the uncontrollability of the sea / A polite interpretation of "sea phobia" / The connection between the "Grand Canal of China," listed as a World Cultural Heritage, and the Belt and Road Initiative

main

References

Reviews

Search

Opening Remarks: China's "Sea Power" and the "Grand Canal Era"

Was Zheng He a pioneer of maritime China? / A comparison with the 'Age of Exploration' / Was it due to 'European success'? / While simultaneously wary of Eurocentrism and Sinocentrism / How should we understand China's practices that are neither 'sea ban' nor 'open sea ban'? / An era when the Grand Canal enabled us to gauge domestic and foreign logistics trends / Two characteristics of the Grand Canal era in a narrow sense / The structure and narrative style of this book

Chapter 1: 1415: Emperor Yongle prepares to move the capital to Beijing and rebuilds the Grand Canal.

The opening of the Cheonggangpo Port and the 'Paid Shipping' / Paid Shipping / The Giraffe Brought by the Zheng He Expedition / The Dark Shadow of Coup and Massacre / The Move of the Capital to Beijing / The Touchstone of the Success of the Move of the Capital to Beijing: The Reconstruction of the Grand Canal / The Move of the Capital to Beijing and Kublai Khan / Why Did the Yongle Emperor Ban Shipping? / The Significance of the Unification of Shipping through the Grand Canal / The Dispatch of Zheng He and the Increase in Tributary States / Why Did China Hesitate to the Sea After Zheng He? / The Portuguese Occupation of Ceuta in 1415

Chapter 2: 1492: A Huizhou merchant seizes a new opportunity with a change in the salt-cloud law.

1492, the implementation of the Yunsa Nap-eun system by the Qing Dynasty / The salt distribution law of the Ming Dynasty linked to the supply of military supplies to the northern border / 1449, the 'land empire' through the Tomokbo Incident / The first beneficiaries of the Kaizhong Law, Shanxi and Shaanxi merchants / Yangzhou, the central city of the Huaiyang region / The Yunsa Nap-eun system, a golden opportunity for Huizhou merchants / The overseas expansion of Huizhou merchants and the expansion of the Yin economy / The dispatch of the eunuch Luo Bao and the change in the landscape of Yan Shanggui / The choices of Huizhou merchants / Was there no other option? / Implications of Wang Zhi, a Huizhou merchant and maritime expert / Thinking back to 1492

Chapter 3: 1573: Governor-General Wang Jong-mok attempts to transport goods by sea.

1573: A transport ship capsizes at sea / Critical opinions on shipping / Three solutions to appease Beijing's people / The political variable of Zhang Juzheng / 'Pahaeun': Shipping halted again / The world-historical significance of the 1573 shipping 'death'

Chapter 4: 1600: Jesuit missionary Matteo Ricci evaluates the Grand Canal

1600, Matteo Ricci and Xu Guangqi's first meeting / Why was Ricci in Nanjing in 1600? / Ricci, who traveled to and from Beijing using the Grand Canal / Ships carrying foreign tributes / Ricci, who discovered the 'illegal' operation of tribute ships / Matteo Ricci's difficult problem / The truth about the fear of the sea: (1) Japanese pirates / The truth about the fear of the sea: (2) The Imjin War / The truth about the fear of the sea: (3) European armed forces / Xu Guangqi's perception of the frontier / Chinese maritime maps drawn around 1608 / The world historical significance of 1600

Chapter 5: 1666: Salt merchant Jeong Yu-yong rebuilds Cheonbigung Palace.

1666, the relocation and construction of the Yangju Cheonbigung / Jeong Yu-yong's story of rebuilding the Cheonbigung / the formation and spread of the Mazu faith / the change from the sea god to the god of the sea / the restoration of the function of the Yangju Cheonbigung through a change in location / the Grand Canal pile removal project / Jeong Yu-yong's gambit / Adam Schall's death and Yang Gwang-seon's attack / 1666, the 'Year of Wonders'

Chapter 6: 1684: Emperor Kangxi begins his tour of the Jiangnan region using the Grand Canal.

1684, Kangxi Emperor's first tour of the southern part of the Yangtze River / The purpose of the southern tour / A clever plan to simultaneously resolve both the supply of goods and transportation / The establishment of four customs offices / The genealogy of the Zheng clan's maritime power / The side effects of the Tianqi Ling / A new source of vitality for maritime trade / A 'compromise' between security and profit / The significance of the Grand Canal, the emperor's route for southern tours

Chapter 7: 1757: Emperor Qianlong reduces the number of customs offices for Western ships after his Southern Tour.

The identity of the British ships appearing in Ningbo / Concerns about becoming a second Macau / The Qianlong Emperor's second southern tour and its background / The collusion between the Qianlong Emperor and the Yanxiang of Yangzhou / The reduction of the sea gateway from four to one in 1757 / The Qianlong Emperor's fears? / The reality of the concerns and fears (1): Increasing overseas migration and collusion with 'subversive' Western powers / The reality of the concerns and fears (2): The spread of Christianity in the mainland and the expanding Christian network / Why Gwangju? / Maritime policy linked to the northwestern border policy

Chapter 8: 1784: Emperor Qianlong completes his final tour of the Jiangnan region using the Grand Canal.

1784, Emperor Qianlong's sixth southern tour / The regrets of Yangzhou merchants about his last southern tour / The Gwangju Jiaoan Incident of 1784 / Emperor Qianlong's anxiety over the possibility of connections between Westerners and Muslims / The beginning of US-China trade and the 'American impact' / The aftermath of the Lady Hughes incident / The end of the Grand Canal era, 1784

Concluding Remarks: The End of the 'Grand Canal Era' and What Happened Afterward

Why I hesitated to use the word "hesitant"? / Lack of motivation to advance into the sea? / Threat from northern peoples? / Deficiency and threat theories seen through the Grand Canal, an icon of inter-Korean unification / "Fear" and "controlled openness" regarding the uncontrollability of the sea / A polite interpretation of "sea phobia" / The connection between the "Grand Canal of China," listed as a World Cultural Heritage, and the Belt and Road Initiative

main

References

Reviews

Search

Into the book

After Jeonghwa's death, the shipyard was dismantled, the crews were all dismissed, and the ships were left to rot away.

The emperors severely punished Chinese people who went abroad.

Fearing being implicated in the crime of navigation, the shipbuilders went into deep hiding.

By 1500, it was a grave offense to build a junk with more than two masts.

Within a generation, the Chinese had lost the skill to build large ships like the Bosun, and civilian vessels stopped venturing beyond the Straits of Malacca.

--- p.78

In his analysis of the origins of pirates, Tang Chu said, “Pirates and pirates are the same people.

“If trade is permitted, the trench turns into the sea, but if trade is prohibited, the sea turns into a trench,” he pointed out.

Essentially, at that time, the trench and the sea were like two sides of the same coin.

--- p.124

The fear of Japan, which caused the Imjin War, also influenced subsequent policies toward Ryukyu and Taiwan.

In 1609, shortly after Japan annexed Ryukyu, a loyal tributary state of the Ming Dynasty, the Ming Dynasty became aware of this fact, but effectively watched without any official response.

At that time, intellectuals from the coastal areas who had even a little knowledge of the Ryukyu situation and could discern reason shared the common understanding that it was impossible for China to cross the Great Sea to rescue Ryukyu from Japan's attack.

--- p.182

The burden felt by the officials and people of the regions along the southern route each time the southern expedition took place was not insignificant.

First of all, the average duration of the Southern Tour was 115 days, which was longer than the Western Tour, Eastern Tour, and Northern Tour during the Qianlong era, which took an average of 36 days, 60 days, and 88 days, respectively.

The number of people accompanying the Southern Expedition was also over 3,000, which was larger than those traveling in other directions.

The number of four-legged animals, including horses, mules, and camels, that traveled with the entourage was close to 10,000.

--- p.269

The White Lotus Rebellion (1796-1804), which broke out as if waiting for the Qianlong Emperor to abdicate the throne, showed how deep the rift of poverty and discontent had become amidst the abundance that could not be covered up by the fabrication of a prosperous era.

How could the beacon fires that have been blazing across the continent since the White Lotus Sect's uprising be concealed by a terrestrial blast? While the inland was in turmoil due to the White Lotus Sect's uprising, pirates also rose up like wildfire at sea.

The emperors severely punished Chinese people who went abroad.

Fearing being implicated in the crime of navigation, the shipbuilders went into deep hiding.

By 1500, it was a grave offense to build a junk with more than two masts.

Within a generation, the Chinese had lost the skill to build large ships like the Bosun, and civilian vessels stopped venturing beyond the Straits of Malacca.

--- p.78

In his analysis of the origins of pirates, Tang Chu said, “Pirates and pirates are the same people.

“If trade is permitted, the trench turns into the sea, but if trade is prohibited, the sea turns into a trench,” he pointed out.

Essentially, at that time, the trench and the sea were like two sides of the same coin.

--- p.124

The fear of Japan, which caused the Imjin War, also influenced subsequent policies toward Ryukyu and Taiwan.

In 1609, shortly after Japan annexed Ryukyu, a loyal tributary state of the Ming Dynasty, the Ming Dynasty became aware of this fact, but effectively watched without any official response.

At that time, intellectuals from the coastal areas who had even a little knowledge of the Ryukyu situation and could discern reason shared the common understanding that it was impossible for China to cross the Great Sea to rescue Ryukyu from Japan's attack.

--- p.182

The burden felt by the officials and people of the regions along the southern route each time the southern expedition took place was not insignificant.

First of all, the average duration of the Southern Tour was 115 days, which was longer than the Western Tour, Eastern Tour, and Northern Tour during the Qianlong era, which took an average of 36 days, 60 days, and 88 days, respectively.

The number of people accompanying the Southern Expedition was also over 3,000, which was larger than those traveling in other directions.

The number of four-legged animals, including horses, mules, and camels, that traveled with the entourage was close to 10,000.

--- p.269

The White Lotus Rebellion (1796-1804), which broke out as if waiting for the Qianlong Emperor to abdicate the throne, showed how deep the rift of poverty and discontent had become amidst the abundance that could not be covered up by the fabrication of a prosperous era.

How could the beacon fires that have been blazing across the continent since the White Lotus Sect's uprising be concealed by a terrestrial blast? While the inland was in turmoil due to the White Lotus Sect's uprising, pirates also rose up like wildfire at sea.

--- p.332

Publisher's Review

If there was an age of exploration in Europe

China has its Grand Canal era.

Professor Cho Young-heon, who presented a new paradigm for the study of modern Chinese history with his book “The Grand Canal and Chinese Merchants,” presents his first book in 10 years.

This book captures China's 'Ming and Qing Dynasties' with the groundbreaking concept of the 'Grand Canal Era'.

China, once the world's wealthiest and most powerful empire, prospered from the 15th to the 18th centuries by transporting goods, people, and information through the Grand Canal, which stretched for approximately 1,800 kilometers.

However, the era of the Grand Canal was also a paradoxical one, as it further strengthened China's "sea phobia" and brought about the decline of the empire.

Through vivid episodes featuring a variety of characters, including emperors, officials, merchants, pirates, and missionaries, the author elevates the era of the Grand Canal to a time in world history comparable to the Age of Exploration.

The Grand Canal, the world's largest inland waterway transport network,

Making the frontier city of Beijing the imperial capital

When we talk about the Grand Canal of China, we usually think of the Grand Canal of the Sui Dynasty.

However, the Grand Canal covered in this book was completed about 800 years after the Grand Canal of the Sui Dynasty, by the Yongle Emperor, the third emperor of the Ming Dynasty.

Immediately after ascending to the throne, Emperor Yongle pushed for the relocation of the capital.

I was thinking of leaving Nanjing and moving to Beijing.

Many historians have tried to explain the 'reasons' for moving the capital to Beijing.

Beijing was too close to Mongolia, and the land was barren.

Moreover, it was too far from the Gangnam area, the economic center.

The Ming was not a conquering dynasty with northern origins like the Jin or Yuan.

The author focuses on the ‘process’ of moving the capital to Beijing.

Before moving the capital, Emperor Yongle embarked on a large-scale project to renovate the Grand Canal.

By equalizing the water depth in areas with different elevations, building embankments to prevent flooding, and installing locks to divert the water flow, previously blocked sections were reopened.

The waterway thus completed was capable of transporting an incomparable amount of goods compared to the Grand Canal of the previous era.

The Grand Canal met the requirements for moving the capital to Beijing.

Once the supply problem was resolved, Emperor Yongle formalized the relocation of the capital, and the structure established at that time with Beijing as the political center and Jiangnan as the economic center continues to this day.

Both prosperity and decline began with the Grand Canal.

Why did China close its doors?

As we have seen, the capital city of Beijing was under threat from the Mongols, and the salt merchants of the Grand Canal played a crucial role in ensuring its security.

As the Grand Canal was redeveloped, the production and distribution of salt, which had declined during the Yuan Dynasty, became active again.

All of China's dynasties held a monopoly on salt, and this was true even during the Ming Dynasty.

In exchange for the right to sell salt from the government, salt merchants directly procured military supplies from the northern border, and after the system was changed, they contributed to national defense by paying silver.

Jeong Youyong, an early Qing merchant who operated on the Grand Canal, provides a noteworthy example.

Jeong Yu-yong and his fellow merchants used their own money to rebuild the Cheonbi Palace in Yangju, a city on the Grand Canal. Cheonbi refers to the god of navigation, Mazu.

The Grand Canal was so prosperous that the sea goddess was worshipped as the goddess of the canal inland during this period.

It is also worth noting that a mere merchant, not even a manager, had such high status that he was leading a public service project in the local community.

But there was a dark side to the Grand Canal's prosperity.

After opening the Grand Canal, Emperor Yongle prohibited shipping by sea.

Accordingly, Wang Zhongmu, who served as the Governor-General of Zhao during the reign of Emperor Wanli of the Ming Dynasty, proposed that grain be transported from the south to the capital using not only the Grand Canal but also the sea.

It was a reasonable argument.

Floods of the Yellow River periodically threatened the smooth passage of the Grand Canal, and as Matteo Ricci, a Jesuit missionary who later visited China, later testified, the canal was so swamped that it became a traffic jam with ships waiting their turn to pass.

What happened to Wang Zhongmok's proposal? Wang Zhongmok was overthrown, and China once again lost its chance to advance to the sea.

Although the apparent cause was political conflict, the author finds the real cause in the “fear of pirates invading the sea and coasts” raised by Matteo Ricci.

Both the Ming and Qing dynasties adopted the "sea ban" policy, which prohibited going out to sea, as their basic policy, and this policy was further strengthened by the outbreak of the Imjin War, the proliferation of Japanese pirates on the southeastern coast, and the advance of European armed forces.

Why did China hesitate to advance into the maritime arena?

How should we view China's 'maritime rise' in the 21st century?

In 1684, the Kangxi Emperor of the Qing Dynasty permitted the establishment of customs offices in Shanghai, Ningbo, Xiamen, and Guangzhou to handle maritime trade.

It was an unprecedented level of openness, and it seemed like a display of confidence that had broken the Zheng clan's power in Taiwan the previous year.

However, Westerners who had advanced into East Asia continued to demand additional openings, and Emperor Qianlong, Kangxi's grandson, responded by closing three of the four customs offices.

For the Qianlong Emperor, preventing threats from the sea was more important than profiting from trade.

At that time, the Qing Dynasty was enjoying its heyday to the point where it did not feel the need to advance into the sea.

Just as his grandfather, Emperor Kangxi, toured the Jiangnan region six times, Emperor Qianlong also visited the Jiangnan region six times.

If Emperor Kangxi's Southern Tour focused on appeasing the people and observing the situation of flood control, Emperor Qianlong's Southern Tour had more of a nature of a cruise along the Grand Canal.

Emperor Qianlong's tour of the Jiangnan region was a good opportunity for merchants along the Grand Canal.

They gained honor and privilege by treating the emperor with great respect.

Emperor Qianlong was also able to display the power of a stable and unified empire by strengthening ties with influential figures in the Jiangnan region through the Southern Tour.

The Grand Canal era was at its peak, and nothing seemed to be lacking.

The author believes that the Grand Canal can enhance the persuasive power of the logic of "land is vast and goods are abundant" (地大物博), which is often cited as the reason why China was hesitant to advance into the sea, i.e., that it did not advance into the sea because its land was vast and goods were abundant.

The Grand Canal facilitated the flow of goods between the north and south within the vast empire, promoted balanced development, and prevented the feeling of 'deficiency'.

So why has today's China pursued a maritime policy so radically different from its past? China has recently re-examined the expedition of the Zheng He fleet, which reportedly reached Africa during the Yongle era. It has also emphasized the Maritime Silk Road alongside the overland Silk Road through its Belt and Road Initiative, which has led to claims of sovereignty in the South China Sea.

In this context of reinterpreting history through neo-liberal propaganda, looking back at the rise and fall of the Grand Canal era and considering why China hesitated to advance into the sea will provide valuable clues to understanding China's "maritime rise" in the 21st century as it strives to become a maritime power.

China has its Grand Canal era.

Professor Cho Young-heon, who presented a new paradigm for the study of modern Chinese history with his book “The Grand Canal and Chinese Merchants,” presents his first book in 10 years.

This book captures China's 'Ming and Qing Dynasties' with the groundbreaking concept of the 'Grand Canal Era'.

China, once the world's wealthiest and most powerful empire, prospered from the 15th to the 18th centuries by transporting goods, people, and information through the Grand Canal, which stretched for approximately 1,800 kilometers.

However, the era of the Grand Canal was also a paradoxical one, as it further strengthened China's "sea phobia" and brought about the decline of the empire.

Through vivid episodes featuring a variety of characters, including emperors, officials, merchants, pirates, and missionaries, the author elevates the era of the Grand Canal to a time in world history comparable to the Age of Exploration.

The Grand Canal, the world's largest inland waterway transport network,

Making the frontier city of Beijing the imperial capital

When we talk about the Grand Canal of China, we usually think of the Grand Canal of the Sui Dynasty.

However, the Grand Canal covered in this book was completed about 800 years after the Grand Canal of the Sui Dynasty, by the Yongle Emperor, the third emperor of the Ming Dynasty.

Immediately after ascending to the throne, Emperor Yongle pushed for the relocation of the capital.

I was thinking of leaving Nanjing and moving to Beijing.

Many historians have tried to explain the 'reasons' for moving the capital to Beijing.

Beijing was too close to Mongolia, and the land was barren.

Moreover, it was too far from the Gangnam area, the economic center.

The Ming was not a conquering dynasty with northern origins like the Jin or Yuan.

The author focuses on the ‘process’ of moving the capital to Beijing.

Before moving the capital, Emperor Yongle embarked on a large-scale project to renovate the Grand Canal.

By equalizing the water depth in areas with different elevations, building embankments to prevent flooding, and installing locks to divert the water flow, previously blocked sections were reopened.

The waterway thus completed was capable of transporting an incomparable amount of goods compared to the Grand Canal of the previous era.

The Grand Canal met the requirements for moving the capital to Beijing.

Once the supply problem was resolved, Emperor Yongle formalized the relocation of the capital, and the structure established at that time with Beijing as the political center and Jiangnan as the economic center continues to this day.

Both prosperity and decline began with the Grand Canal.

Why did China close its doors?

As we have seen, the capital city of Beijing was under threat from the Mongols, and the salt merchants of the Grand Canal played a crucial role in ensuring its security.

As the Grand Canal was redeveloped, the production and distribution of salt, which had declined during the Yuan Dynasty, became active again.

All of China's dynasties held a monopoly on salt, and this was true even during the Ming Dynasty.

In exchange for the right to sell salt from the government, salt merchants directly procured military supplies from the northern border, and after the system was changed, they contributed to national defense by paying silver.

Jeong Youyong, an early Qing merchant who operated on the Grand Canal, provides a noteworthy example.

Jeong Yu-yong and his fellow merchants used their own money to rebuild the Cheonbi Palace in Yangju, a city on the Grand Canal. Cheonbi refers to the god of navigation, Mazu.

The Grand Canal was so prosperous that the sea goddess was worshipped as the goddess of the canal inland during this period.

It is also worth noting that a mere merchant, not even a manager, had such high status that he was leading a public service project in the local community.

But there was a dark side to the Grand Canal's prosperity.

After opening the Grand Canal, Emperor Yongle prohibited shipping by sea.

Accordingly, Wang Zhongmu, who served as the Governor-General of Zhao during the reign of Emperor Wanli of the Ming Dynasty, proposed that grain be transported from the south to the capital using not only the Grand Canal but also the sea.

It was a reasonable argument.

Floods of the Yellow River periodically threatened the smooth passage of the Grand Canal, and as Matteo Ricci, a Jesuit missionary who later visited China, later testified, the canal was so swamped that it became a traffic jam with ships waiting their turn to pass.

What happened to Wang Zhongmok's proposal? Wang Zhongmok was overthrown, and China once again lost its chance to advance to the sea.

Although the apparent cause was political conflict, the author finds the real cause in the “fear of pirates invading the sea and coasts” raised by Matteo Ricci.

Both the Ming and Qing dynasties adopted the "sea ban" policy, which prohibited going out to sea, as their basic policy, and this policy was further strengthened by the outbreak of the Imjin War, the proliferation of Japanese pirates on the southeastern coast, and the advance of European armed forces.

Why did China hesitate to advance into the maritime arena?

How should we view China's 'maritime rise' in the 21st century?

In 1684, the Kangxi Emperor of the Qing Dynasty permitted the establishment of customs offices in Shanghai, Ningbo, Xiamen, and Guangzhou to handle maritime trade.

It was an unprecedented level of openness, and it seemed like a display of confidence that had broken the Zheng clan's power in Taiwan the previous year.

However, Westerners who had advanced into East Asia continued to demand additional openings, and Emperor Qianlong, Kangxi's grandson, responded by closing three of the four customs offices.

For the Qianlong Emperor, preventing threats from the sea was more important than profiting from trade.

At that time, the Qing Dynasty was enjoying its heyday to the point where it did not feel the need to advance into the sea.

Just as his grandfather, Emperor Kangxi, toured the Jiangnan region six times, Emperor Qianlong also visited the Jiangnan region six times.

If Emperor Kangxi's Southern Tour focused on appeasing the people and observing the situation of flood control, Emperor Qianlong's Southern Tour had more of a nature of a cruise along the Grand Canal.

Emperor Qianlong's tour of the Jiangnan region was a good opportunity for merchants along the Grand Canal.

They gained honor and privilege by treating the emperor with great respect.

Emperor Qianlong was also able to display the power of a stable and unified empire by strengthening ties with influential figures in the Jiangnan region through the Southern Tour.

The Grand Canal era was at its peak, and nothing seemed to be lacking.

The author believes that the Grand Canal can enhance the persuasive power of the logic of "land is vast and goods are abundant" (地大物博), which is often cited as the reason why China was hesitant to advance into the sea, i.e., that it did not advance into the sea because its land was vast and goods were abundant.

The Grand Canal facilitated the flow of goods between the north and south within the vast empire, promoted balanced development, and prevented the feeling of 'deficiency'.

So why has today's China pursued a maritime policy so radically different from its past? China has recently re-examined the expedition of the Zheng He fleet, which reportedly reached Africa during the Yongle era. It has also emphasized the Maritime Silk Road alongside the overland Silk Road through its Belt and Road Initiative, which has led to claims of sovereignty in the South China Sea.

In this context of reinterpreting history through neo-liberal propaganda, looking back at the rise and fall of the Grand Canal era and considering why China hesitated to advance into the sea will provide valuable clues to understanding China's "maritime rise" in the 21st century as it strives to become a maritime power.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: August 20, 2021

- Format: Hardcover book binding method guide

- Page count, weight, size: 464 pages | 688g | 152*225*30mm

- ISBN13: 9788937444555

- ISBN10: 8937444550

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)