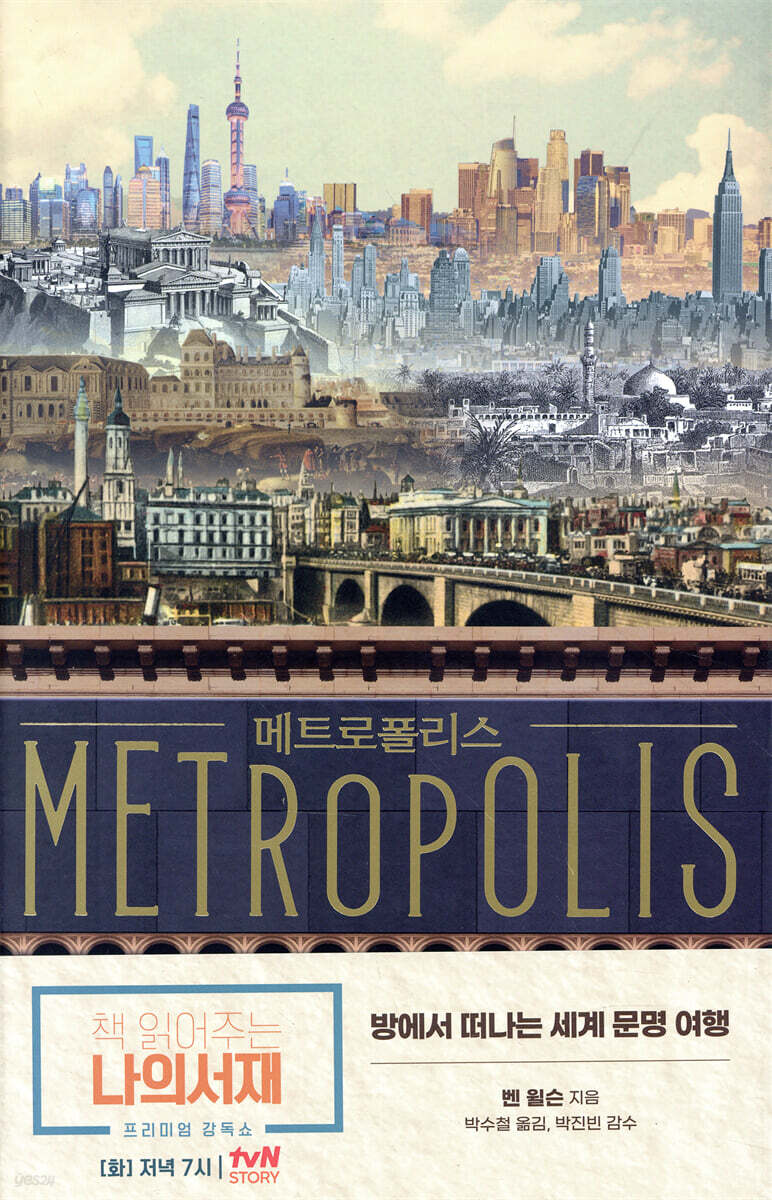

Metropolis

|

Description

Book Introduction

Athens, Rome, Amsterdam, Baghdad, London, Paris, New York… A world-class voyage of discovery, exploring 26 cities that shaped human civilization over 6,000 years. - How were cities born, and how did they dominate human life? - How are the fruits of civilization, such as politics, international trade, technological advancement, and art, conceived within the history of cities? - What direction should future cities take, overcoming crises like climate change and pandemics? The history of cities is the history of mankind. Since the birth of the first city in 4000 BC, all aspects of human civilization, including politics, economics, culture, religion, and art, have followed the development and trajectory of cities. This book traces the development of human civilization through the history of the city, humanity's greatest invention, and discusses the future direction of cities and human civilization as they face critical crises such as pandemics and environmental pollution. Ben Wilson, a promising British historian and author of this book, examines 26 cities in chronological order that have shaped human civilization over a total of 6,000 years, from the founding of the first city, Uruk, to the present day. And within the city's history, it unfolds fascinating stories of human civilization set against the backdrop of the city, including commerce, international trade, art, prostitution, hygiene, bathhouses, street food, and social interaction. As we follow the great voyages of world history that transcend time and space and travel to cities around the world, we are forced to look at the city we live in objectively and think about the human activities and civilization that unfold within it. |

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Preface: The Century of the Metropolis

Preface to the Korean edition

world map

Chapter 1: Dawn of the City

Uruk, 4000–1900 BC

Chapter 2: The Garden of Eden and the City of Sin

Harappa and Babylon, 2000–539 BC

Chapter 3: International Cities

Athens and Alexandria, 507–30 BC

Chapter 4: Pleasures in the Bath

Rome, 30 BC–AD 537

Chapter 5: A Colorful Feast of Cuisine

Baghdad, 537–1258

Chapter 6 Freedom Brought by War

Lübeck, 1226–1491

Chapter 7: The Heart of Commerce and Trade

Lisbon, Malacca, Tenochtitlan, Amsterdam

1492~1666

Chapter 8: Caffeine Community and Socializing

London, 1666–1820

Chapter 9: Hell on Earth

Manchester and Chicago, 1830–1914

Chapter 10: Paris Syndrome

Paris, 1830–1914

Chapter 11: Shadows Cast by Skyscrapers

New York, 1899–1939

Chapter 12 Annihilation

Warsaw 1939–1945

Chapter 13: Desire Overflowing into the Suburbs

Los Angeles, 1945–1999

Chapter 14: A Future City Vibrant with Dynamism

Lagos, 1999–2020

Acknowledgements

Americas

index

Preface to the Korean edition

world map

Chapter 1: Dawn of the City

Uruk, 4000–1900 BC

Chapter 2: The Garden of Eden and the City of Sin

Harappa and Babylon, 2000–539 BC

Chapter 3: International Cities

Athens and Alexandria, 507–30 BC

Chapter 4: Pleasures in the Bath

Rome, 30 BC–AD 537

Chapter 5: A Colorful Feast of Cuisine

Baghdad, 537–1258

Chapter 6 Freedom Brought by War

Lübeck, 1226–1491

Chapter 7: The Heart of Commerce and Trade

Lisbon, Malacca, Tenochtitlan, Amsterdam

1492~1666

Chapter 8: Caffeine Community and Socializing

London, 1666–1820

Chapter 9: Hell on Earth

Manchester and Chicago, 1830–1914

Chapter 10: Paris Syndrome

Paris, 1830–1914

Chapter 11: Shadows Cast by Skyscrapers

New York, 1899–1939

Chapter 12 Annihilation

Warsaw 1939–1945

Chapter 13: Desire Overflowing into the Suburbs

Los Angeles, 1945–1999

Chapter 14: A Future City Vibrant with Dynamism

Lagos, 1999–2020

Acknowledgements

Americas

index

Detailed image

.jpg)

Into the book

Throughout history, cities have been identified as fundamentally antithetical to our nature and temperament, fostering vice, fostering disease, and causing social ills.

Babylonian mythology has resonated from time immemorial to the present day.

While cities have had a glittering history of success, they can also lead us to ruin.

There are many wonderful things about big cities, but there are also many scary things about them.

So, the idea of embracing this hostile environment, the city, and adapting it to our needs is incredibly appealing.

The city I see in this book is not only a place of power and profit, but also a place that has a profound impact on the lives of its residents.

Metropolis is not a book about grand buildings or urban planning.

The theme of this book is about city dwellers and the ways they have found to cope with and overcome the pressures of city life.

---From "Preface: The Century of the Metropolis"

Several ditches and pits discovered at Uruk are thought to be the remains of a large copper foundry that would have employed around 40 workers.

Many women in Uruk wove fine fabrics from sheep's wool on horizontal floor looms that could maintain high production levels.

Uruk potters employed two significant innovations: the Mesopotamian beehive kiln and the high-speed potter's wheel.

The honeycomb kiln allowed for significantly higher firing temperatures while protecting the pottery from flames.

Previous potters used a turntable (a stone disc that was turned by hand and fitted onto a lower spindle).

By the Uruk period, however, the rotating device was moved by stick or hand and was connected to a wheel-shaped device above the clay by a shaft.

Thanks to this technology, the Uruk people were able to make pottery much faster and much better.

They produced finely textured, lightweight tableware aimed at the luxury market.

They also had the ability to mass-produce relatively crude goods, such as standardized pottery and storage jars. This series of inventions and improvements was possible only when humans were gathered in a dense and competitive environment.

Innovation breeds innovation.

The high temperatures of the honeycomb kiln were used to experiment with metallurgy and chemistry.

Mesopotamian sailors were the first to use sails.

It is an impressive, counterintuitive fact that the city of Uruk was invented before the wheel.

---From "Chapter 1: Dawn of the City, Uruk"

At its peak, Babylon was considered an unrivaled center of knowledge and art, and a sacred city.

Hippocrates, the Greek father of medicine, relied on the data of Babylonian scholars when mathematics and astronomy were advanced in Babylon.

The Babylonians had a passion for history.

Like 19th-century archaeologists, Babylonian scholars traveled throughout Mesopotamia, seeking to understand its 3,000-year history, resulting in countless museums, libraries, and archives.

In addition, Mesopotamian literature flourished based on the myths and legends collected by Babylonian scholars through field research.

Unfortunately, Babylon suffered from an enduring bad reputation because of one of the many ethnic groups that were brought there.

The people regarded Babylon as a place of divine punishment ordained by God to punish them for their sins, and the books they wrote became the foundation of three of the world's major religions.

The hideous image of Babylon was passed on to Christianity.

By the time the age of Christ arrived, Babylon had lost its former glory, but had become a byword for sin, corruption, and tyranny.

The book of Revelation had the greatest influence of all.

The Book of Revelation, with its hallucinatory and dynamic prose of apocalypse, sin, and salvation, has forever entrenched Babylon in the collective memory of Christians and in the culture that grew out of it.

The way Babylon was portrayed by its enemies and victims has had a profound impact on how people have viewed major cities ever since.

---From "Chapter 2: The Garden of Eden and the Cities of Sin: Harappa and Babylon"

Important figures flaunted their status and wealth by entering the bathhouse with naked attendants.

People went to the bathhouse to get work done, discuss politics, have a chat, or get invited to dinner.

They also went to the bathhouse to see something or someone, or to be noticed.

They ate, they drank, they argued, they flirted, and sometimes they had sex in a small room.

He even left graffiti on the marble.

After making plans to eat together, we enjoyed a bath before eating.

In the bathhouse, wine was readily available.

The spacious and comfortable imperial public baths were filled with the cacophony of thousands of people talking and arguing, to the cries of vendors selling bread, candy, drinks, and simple snacks.

The weightlifters groaned and panted.

Someone shouted out the score of a nearby game of ball.

The sound of the masseuses gently patting the flesh with their hands filled the round ceiling.

To my ears, some people even sang while enjoying their bath.

Guests crowded around performers such as tossers, clowns, jugglers, magicians, and gymnasts.

[…] The bathhouse offered a unique and diverse urban experience.

Above all, I was able to experience joint activities.

The rich and the poor had a close relationship.

We made a friendship and it became stronger.

A business deal was attempted.

The sound of conversation was loud here and there.

Such opportunities for socialization, in whatever form they took, were probably the main pleasure of bathing, and so the Romans would not have hesitated to invest time in it.

A boy from Rome wrote the following excitedly after class:

“I need to go and take a bath quickly.

Yeah, it's time.

let's go.

Let's follow the servant, holding a few towels.

“I have to chase after all the guests heading to the bathhouse and say, ‘Hello! Enjoy your bath! Enjoy your dinner!’”

---From "Chapter 4: Pleasures in the Bathhouse, Rome"

Amsterdam's vibrant energy was masked by its pleasant, tranquil atmosphere, its distinctive architectural consistency, and the sober dress of its citizens.

Amsterdam had no monuments or boulevards, but the city's true glory was its citizens' homes.

Peter Mundy, an English traveler who visited Amsterdam in 1640, was impressed by the “neat and clean” dwellings of ordinary citizens “full of joy and contentment.”

Their living quarters contained “expensive and novel” furniture and decorations, such as cupboards and wardrobes, paintings and prints, porcelain, and “costly and exquisite birdcages.”

The average Dutch household was an avid consumer of art.

According to Mundy, not only did middle-class homes have a wealth of paintings and sculptures, but even butcher shops and blacksmith shops had oil paintings.

It was one of millions of paintings produced by countless 17th-century artists.

In that overflowing wave of artistic talent, there was the life of a city and the chaos that arose on its streets.

The drunkards of the tavern became protagonists, no different from the tycoons of the stock exchange.

The paintings of that time do not depict idealized cityscapes of the past, but rather the harsh realities of city life and the impressions the painter felt there.

The comical and enigmatic events that occur, the contrasts in types, the liveliness and energy of city life are a regular theme in modern art, literature, music and film.

The roots of city life lie in 17th-century Dutch genre painting, particularly depictions of Amsterdam's lively taverns.

People drink, smoke, flirt, kiss, fight, play music, gamble, eat like crazy, and sleep.

The chaos, confusion and movement of that moment are captured by the painter.

In Dutch genre painting, a new way of city life is celebrated.

The tavern is likely to be a place of humor and moral instruction.

But the small but wonderful house of the middle class is an object of blind worship.

Such houses seem very close to urban living, and stand out for their unique neatness and harmony.

Housewives and maids sweep and clean the house.

Open your underwear.

Scrub the pot and pan clean.

Work hard at odd jobs.

The children play quietly.

The inside of the house is clean without a speck of dust.

Amsterdammers were known for being fastidious about hygiene and cleanliness.

There were many paintings that praised ideal virtues such as neatness and the perfect family, as if to counter the rotten smell of the wealthy and profit-driven global city.

That holy home was like a levee that held back the tidal wave of the city's vices.

It seemed like a necessary antidote to the rotten stench of the tavern and the harsh world of capitalism.

It was also a new urban world where noble and wealthy women lived away from the filthy, messy and immoral city life.

The dangerous and unclean streets were a man's world.

In other words, it was a world that did not suit women who were supposed to create an ideal family.

---From "Chapter 7: The Hearts of Commerce and Trade: Lisbon, Malacca, Tenochtitlan, and Amsterdam"

In late 17th-century London, news had become a valuable commodity, and coffeehouses had become centers of news.

England and Scotland, embroiled in the civil war of the 1640s that led to the execution of the king, were still politically turbulent when Pascal Rose opened his coffee shop.

Between 1659 and 1660, the political situation was once again in crisis due to a struggle for power between factions.

Coffee shops proved valuable during those turbulent times as places for discussion and news exchange.

Samuel Pepys, a young man curious about news and world affairs and thirsty for connections with powerful figures, frequented coffeehouses to watch debates.

At the Turk's Head coffeehouse in Westminster, he socialized with aristocrats, political thinkers, merchants, soldiers, and scholars who discussed the future of the country.

Those who watched the debate, like Fifth, were amazed at the depth and politeness of the discussion that took place in the coffee shop.

That kind of atmosphere could not be created in a tavern or an inn.

There was something about that hot, dark drink you taste in a coffee shop that helped you calm down and have better judgment.

Guests drank drinks typical of big cities and behaved in big city ways.

The coffee shop's regulars not only consumed news, they also produced it.

Journalists got their stories from the gossip circulating in the bustling coffee shops.

Government spies combed through such rumors to find out the latest information.

Anyway, now the world's affairs are openly discussed in the specific environment of a coffee shop.

In a coffee shop, you had to sit down when a seat became available.

I had to sit down no matter who was next to me.

There were no special seats reserved for the nobles.

According to Samuel Butler, 'the coffeehouse was a place where people of all ranks and status could discuss foreign drinks, news, beer and cigarettes.'

The coffee shop owner did not tolerate 'discrimination against people', and gentlemen, artisans, nobles, and gangsters all mingled together, and they all lived in harmony as if they were practicing the first principle themselves.

The government feared the ramifications of this radical new public space, and saw coffeehouses as hotbeds of sedition and republicanism.

Coffee shops, which had emerged as a new trend, were repeatedly attacked through publications.

Criticism often aimed below the belt.

The authors of The Women's Petition Against Coffee wrote:

“Because of that abominable and heathenish liquid, which is so fashionable lately, called coffee, our husbands have become sapped of their virility, our more amiable lovers have become withered and old, and have become as useless as the desert from which that unfortunate fruit springs.

Babylonian mythology has resonated from time immemorial to the present day.

While cities have had a glittering history of success, they can also lead us to ruin.

There are many wonderful things about big cities, but there are also many scary things about them.

So, the idea of embracing this hostile environment, the city, and adapting it to our needs is incredibly appealing.

The city I see in this book is not only a place of power and profit, but also a place that has a profound impact on the lives of its residents.

Metropolis is not a book about grand buildings or urban planning.

The theme of this book is about city dwellers and the ways they have found to cope with and overcome the pressures of city life.

---From "Preface: The Century of the Metropolis"

Several ditches and pits discovered at Uruk are thought to be the remains of a large copper foundry that would have employed around 40 workers.

Many women in Uruk wove fine fabrics from sheep's wool on horizontal floor looms that could maintain high production levels.

Uruk potters employed two significant innovations: the Mesopotamian beehive kiln and the high-speed potter's wheel.

The honeycomb kiln allowed for significantly higher firing temperatures while protecting the pottery from flames.

Previous potters used a turntable (a stone disc that was turned by hand and fitted onto a lower spindle).

By the Uruk period, however, the rotating device was moved by stick or hand and was connected to a wheel-shaped device above the clay by a shaft.

Thanks to this technology, the Uruk people were able to make pottery much faster and much better.

They produced finely textured, lightweight tableware aimed at the luxury market.

They also had the ability to mass-produce relatively crude goods, such as standardized pottery and storage jars. This series of inventions and improvements was possible only when humans were gathered in a dense and competitive environment.

Innovation breeds innovation.

The high temperatures of the honeycomb kiln were used to experiment with metallurgy and chemistry.

Mesopotamian sailors were the first to use sails.

It is an impressive, counterintuitive fact that the city of Uruk was invented before the wheel.

---From "Chapter 1: Dawn of the City, Uruk"

At its peak, Babylon was considered an unrivaled center of knowledge and art, and a sacred city.

Hippocrates, the Greek father of medicine, relied on the data of Babylonian scholars when mathematics and astronomy were advanced in Babylon.

The Babylonians had a passion for history.

Like 19th-century archaeologists, Babylonian scholars traveled throughout Mesopotamia, seeking to understand its 3,000-year history, resulting in countless museums, libraries, and archives.

In addition, Mesopotamian literature flourished based on the myths and legends collected by Babylonian scholars through field research.

Unfortunately, Babylon suffered from an enduring bad reputation because of one of the many ethnic groups that were brought there.

The people regarded Babylon as a place of divine punishment ordained by God to punish them for their sins, and the books they wrote became the foundation of three of the world's major religions.

The hideous image of Babylon was passed on to Christianity.

By the time the age of Christ arrived, Babylon had lost its former glory, but had become a byword for sin, corruption, and tyranny.

The book of Revelation had the greatest influence of all.

The Book of Revelation, with its hallucinatory and dynamic prose of apocalypse, sin, and salvation, has forever entrenched Babylon in the collective memory of Christians and in the culture that grew out of it.

The way Babylon was portrayed by its enemies and victims has had a profound impact on how people have viewed major cities ever since.

---From "Chapter 2: The Garden of Eden and the Cities of Sin: Harappa and Babylon"

Important figures flaunted their status and wealth by entering the bathhouse with naked attendants.

People went to the bathhouse to get work done, discuss politics, have a chat, or get invited to dinner.

They also went to the bathhouse to see something or someone, or to be noticed.

They ate, they drank, they argued, they flirted, and sometimes they had sex in a small room.

He even left graffiti on the marble.

After making plans to eat together, we enjoyed a bath before eating.

In the bathhouse, wine was readily available.

The spacious and comfortable imperial public baths were filled with the cacophony of thousands of people talking and arguing, to the cries of vendors selling bread, candy, drinks, and simple snacks.

The weightlifters groaned and panted.

Someone shouted out the score of a nearby game of ball.

The sound of the masseuses gently patting the flesh with their hands filled the round ceiling.

To my ears, some people even sang while enjoying their bath.

Guests crowded around performers such as tossers, clowns, jugglers, magicians, and gymnasts.

[…] The bathhouse offered a unique and diverse urban experience.

Above all, I was able to experience joint activities.

The rich and the poor had a close relationship.

We made a friendship and it became stronger.

A business deal was attempted.

The sound of conversation was loud here and there.

Such opportunities for socialization, in whatever form they took, were probably the main pleasure of bathing, and so the Romans would not have hesitated to invest time in it.

A boy from Rome wrote the following excitedly after class:

“I need to go and take a bath quickly.

Yeah, it's time.

let's go.

Let's follow the servant, holding a few towels.

“I have to chase after all the guests heading to the bathhouse and say, ‘Hello! Enjoy your bath! Enjoy your dinner!’”

---From "Chapter 4: Pleasures in the Bathhouse, Rome"

Amsterdam's vibrant energy was masked by its pleasant, tranquil atmosphere, its distinctive architectural consistency, and the sober dress of its citizens.

Amsterdam had no monuments or boulevards, but the city's true glory was its citizens' homes.

Peter Mundy, an English traveler who visited Amsterdam in 1640, was impressed by the “neat and clean” dwellings of ordinary citizens “full of joy and contentment.”

Their living quarters contained “expensive and novel” furniture and decorations, such as cupboards and wardrobes, paintings and prints, porcelain, and “costly and exquisite birdcages.”

The average Dutch household was an avid consumer of art.

According to Mundy, not only did middle-class homes have a wealth of paintings and sculptures, but even butcher shops and blacksmith shops had oil paintings.

It was one of millions of paintings produced by countless 17th-century artists.

In that overflowing wave of artistic talent, there was the life of a city and the chaos that arose on its streets.

The drunkards of the tavern became protagonists, no different from the tycoons of the stock exchange.

The paintings of that time do not depict idealized cityscapes of the past, but rather the harsh realities of city life and the impressions the painter felt there.

The comical and enigmatic events that occur, the contrasts in types, the liveliness and energy of city life are a regular theme in modern art, literature, music and film.

The roots of city life lie in 17th-century Dutch genre painting, particularly depictions of Amsterdam's lively taverns.

People drink, smoke, flirt, kiss, fight, play music, gamble, eat like crazy, and sleep.

The chaos, confusion and movement of that moment are captured by the painter.

In Dutch genre painting, a new way of city life is celebrated.

The tavern is likely to be a place of humor and moral instruction.

But the small but wonderful house of the middle class is an object of blind worship.

Such houses seem very close to urban living, and stand out for their unique neatness and harmony.

Housewives and maids sweep and clean the house.

Open your underwear.

Scrub the pot and pan clean.

Work hard at odd jobs.

The children play quietly.

The inside of the house is clean without a speck of dust.

Amsterdammers were known for being fastidious about hygiene and cleanliness.

There were many paintings that praised ideal virtues such as neatness and the perfect family, as if to counter the rotten smell of the wealthy and profit-driven global city.

That holy home was like a levee that held back the tidal wave of the city's vices.

It seemed like a necessary antidote to the rotten stench of the tavern and the harsh world of capitalism.

It was also a new urban world where noble and wealthy women lived away from the filthy, messy and immoral city life.

The dangerous and unclean streets were a man's world.

In other words, it was a world that did not suit women who were supposed to create an ideal family.

---From "Chapter 7: The Hearts of Commerce and Trade: Lisbon, Malacca, Tenochtitlan, and Amsterdam"

In late 17th-century London, news had become a valuable commodity, and coffeehouses had become centers of news.

England and Scotland, embroiled in the civil war of the 1640s that led to the execution of the king, were still politically turbulent when Pascal Rose opened his coffee shop.

Between 1659 and 1660, the political situation was once again in crisis due to a struggle for power between factions.

Coffee shops proved valuable during those turbulent times as places for discussion and news exchange.

Samuel Pepys, a young man curious about news and world affairs and thirsty for connections with powerful figures, frequented coffeehouses to watch debates.

At the Turk's Head coffeehouse in Westminster, he socialized with aristocrats, political thinkers, merchants, soldiers, and scholars who discussed the future of the country.

Those who watched the debate, like Fifth, were amazed at the depth and politeness of the discussion that took place in the coffee shop.

That kind of atmosphere could not be created in a tavern or an inn.

There was something about that hot, dark drink you taste in a coffee shop that helped you calm down and have better judgment.

Guests drank drinks typical of big cities and behaved in big city ways.

The coffee shop's regulars not only consumed news, they also produced it.

Journalists got their stories from the gossip circulating in the bustling coffee shops.

Government spies combed through such rumors to find out the latest information.

Anyway, now the world's affairs are openly discussed in the specific environment of a coffee shop.

In a coffee shop, you had to sit down when a seat became available.

I had to sit down no matter who was next to me.

There were no special seats reserved for the nobles.

According to Samuel Butler, 'the coffeehouse was a place where people of all ranks and status could discuss foreign drinks, news, beer and cigarettes.'

The coffee shop owner did not tolerate 'discrimination against people', and gentlemen, artisans, nobles, and gangsters all mingled together, and they all lived in harmony as if they were practicing the first principle themselves.

The government feared the ramifications of this radical new public space, and saw coffeehouses as hotbeds of sedition and republicanism.

Coffee shops, which had emerged as a new trend, were repeatedly attacked through publications.

Criticism often aimed below the belt.

The authors of The Women's Petition Against Coffee wrote:

“Because of that abominable and heathenish liquid, which is so fashionable lately, called coffee, our husbands have become sapped of their virility, our more amiable lovers have become withered and old, and have become as useless as the desert from which that unfortunate fruit springs.

---From "Chapter 8: Caffeine Communities and Social London"

Publisher's Review

“The most knowledgeable and creative guide to the history of human civilization” - [Time]

“A breathtaking and stunning piece, as if you were visiting the heart-pounding city for the first time.” - [Wall Street Journal]

"A journey through thousands of years of time to 20 cities" - [The New York Times]

The history of the city is the history of mankind!

A great epic about the creation, development, and exchange of civilization!

It is truly the century of the city.

Today, more than half of all humans live in cities, and by 2050, two-thirds of humanity will live in cities.

The seemingly abnormal phenomenon of population concentration, with 20 million people living in Seoul and the Gyeonggi area, is not a problem unique to South Korea.

The world's economy is absolutely dependent on a few metropolitan areas, and this phenomenon is expected to worsen in the future.

In this way, humans have no choice but to live under the dominance of the city, and civilization has blossomed within the urban environment.

But no city in history has ever been perfect.

Efforts to make cities better places often have the opposite effect.

This is not much different today.

Cities around the world, the foundations of human life, have been hit hard by COVID-19.

The irony is that the privileges and dense networks of large cities that were enjoyed through dense populations are now threatening human prosperity and life.

Ben Wilson, author of Metropolis and a promising British historian, asks the following question:

How should human life in the city change? To answer this question, the author guides readers through the history of the city, humanity's greatest invention, and the rise, rise, and decline of cities that have led each era.

Commerce, international trade, art, prostitution, hygiene, bathhouses, street food, socializing…

A variety of themes from the history of human civilization unfold against the backdrop of the city.

In this book, author Ben Wilson, a promising British historian, guides readers through the world of fascinating cities that shaped a certain era of history with delicate and flowing writing.

From ancient cities that once ruled the world but have now faded into dust, to historic cities whose names alone bring a nod of recognition, the colorful and unique history of human life unfolds at a glance, encompassing commerce, trade, prostitution, art, hygiene, bathhouses, street food, and social interaction.

Uruk, the first city that achieved technology, class, currency, numbers, and writing at the cost of distancing itself from nature, which is human nature; Rome, which not only widely praised the reign of the emperor but also devoted itself to building bathhouses as a place for social interaction and community; Baghdad, which indulged in street food that stimulated the five senses and alluring gastronomy; Amsterdam, which enjoyed sophisticated middle-class culture and art as a center of commerce and trade; London, a city of social and commercial life and the birthplace of coffee shops, which can be said to be the origin of Korean-style café culture; Paris, which was prevalent before World War II with its unique culture of pretense or an atmosphere of observing and savoring street life as a "spectator"; Manchester and Chicago, which became hell on earth due to miserable human rights violations and environmental pollution as they entered the post-industrial era; Warsaw, which had to endure the extreme limits of human limitations under the harsh conditions of World War II; and Lagos, a futuristic city that seems complex and least developed, but is alive with the power that has historically made cities the most vibrant and dynamic. From there, we trace human civilization and its trajectory. Through the history of the cities we have worked together, we can gauge the direction of urban development and the potential for the advancement of civilization that we are currently facing.

A city that has never been perfect in history

How to Sustain Beyond the Challenges of Pandemic and Climate Change

In the early 20th century, cities were places of despair, not hope.

Post-industrial society has harmed both human body and mind, and major cities around the world, such as New York and London, have fallen into decline, leaving their city centers empty.

But thanks to cars, telephones, the internet, cheap airfare, and the unhindered flow of capital around the world, people's sphere of activity has expanded like never before.

This allowed the city to regain its former glory.

As cities around the world regain their position as economic hubs, the gap between urban and rural areas is widening dramatically.

Furthermore, as COVID-19 struck the world at a shocking speed, we faced a situation where the close social networks and agglomeration effects between cities actually threatened humanity.

And that's not all.

Two-thirds of the world's major cities are threatened by rising sea levels due to global warming.

Climate change is relentless and threatens humanity at an increasingly dire and unpredictable level.

But Ben Wilson emphasizes that cities are flexible and ever-changing, and that they have solved the problems they face through various transformations and attempts.

Historically, cities have faced countless crises, including epidemics, pandemics, climate change, and economic cycles, but they have overcome them by evolving rather than succumbing to them.

The author argues that entrepreneurship thrives most in the world's dirtiest and most unsanitary slums.

It is said that this dynamism and challenging spirit of the city are the driving force that has evolved the city.

In this context, he focuses on Lagos, a notorious city in Nigeria, Africa.

The true power of urban evolution is revealed in the case of Otigba Computer Village, Africa's largest information and communications technology market with daily sales exceeding $5 million, thanks to the efforts of a small group of self-taught computer enthusiasts.

Seoul, Songdo… Korea's metropolises

Where does the potential to lead this turbulent century come from?

The preface to the Korean edition of this book includes a detailed account of author Ben Wilson's visit to Songdo.

He also confesses that he could feel the vitality, experimentation, and enthusiastic energy of Korean metropolises, including Seoul, full of the qualities that make people attracted to big city life, and says that this is the incomparably important driving force behind the development of Korean metropolises, which have been at the forefront of global urbanism over the past years.

Humans adapt to living in urban environments and change them to suit their needs.

Cities are human homes, and cities evolve and adapt.

Metropolis provides insight into the essence of human life and activities unfolding within the city's history.

It allows us to look back on the place where we live now and to see where the metropolis, the foundation of human life, is heading.

“A breathtaking and stunning piece, as if you were visiting the heart-pounding city for the first time.” - [Wall Street Journal]

"A journey through thousands of years of time to 20 cities" - [The New York Times]

The history of the city is the history of mankind!

A great epic about the creation, development, and exchange of civilization!

It is truly the century of the city.

Today, more than half of all humans live in cities, and by 2050, two-thirds of humanity will live in cities.

The seemingly abnormal phenomenon of population concentration, with 20 million people living in Seoul and the Gyeonggi area, is not a problem unique to South Korea.

The world's economy is absolutely dependent on a few metropolitan areas, and this phenomenon is expected to worsen in the future.

In this way, humans have no choice but to live under the dominance of the city, and civilization has blossomed within the urban environment.

But no city in history has ever been perfect.

Efforts to make cities better places often have the opposite effect.

This is not much different today.

Cities around the world, the foundations of human life, have been hit hard by COVID-19.

The irony is that the privileges and dense networks of large cities that were enjoyed through dense populations are now threatening human prosperity and life.

Ben Wilson, author of Metropolis and a promising British historian, asks the following question:

How should human life in the city change? To answer this question, the author guides readers through the history of the city, humanity's greatest invention, and the rise, rise, and decline of cities that have led each era.

Commerce, international trade, art, prostitution, hygiene, bathhouses, street food, socializing…

A variety of themes from the history of human civilization unfold against the backdrop of the city.

In this book, author Ben Wilson, a promising British historian, guides readers through the world of fascinating cities that shaped a certain era of history with delicate and flowing writing.

From ancient cities that once ruled the world but have now faded into dust, to historic cities whose names alone bring a nod of recognition, the colorful and unique history of human life unfolds at a glance, encompassing commerce, trade, prostitution, art, hygiene, bathhouses, street food, and social interaction.

Uruk, the first city that achieved technology, class, currency, numbers, and writing at the cost of distancing itself from nature, which is human nature; Rome, which not only widely praised the reign of the emperor but also devoted itself to building bathhouses as a place for social interaction and community; Baghdad, which indulged in street food that stimulated the five senses and alluring gastronomy; Amsterdam, which enjoyed sophisticated middle-class culture and art as a center of commerce and trade; London, a city of social and commercial life and the birthplace of coffee shops, which can be said to be the origin of Korean-style café culture; Paris, which was prevalent before World War II with its unique culture of pretense or an atmosphere of observing and savoring street life as a "spectator"; Manchester and Chicago, which became hell on earth due to miserable human rights violations and environmental pollution as they entered the post-industrial era; Warsaw, which had to endure the extreme limits of human limitations under the harsh conditions of World War II; and Lagos, a futuristic city that seems complex and least developed, but is alive with the power that has historically made cities the most vibrant and dynamic. From there, we trace human civilization and its trajectory. Through the history of the cities we have worked together, we can gauge the direction of urban development and the potential for the advancement of civilization that we are currently facing.

A city that has never been perfect in history

How to Sustain Beyond the Challenges of Pandemic and Climate Change

In the early 20th century, cities were places of despair, not hope.

Post-industrial society has harmed both human body and mind, and major cities around the world, such as New York and London, have fallen into decline, leaving their city centers empty.

But thanks to cars, telephones, the internet, cheap airfare, and the unhindered flow of capital around the world, people's sphere of activity has expanded like never before.

This allowed the city to regain its former glory.

As cities around the world regain their position as economic hubs, the gap between urban and rural areas is widening dramatically.

Furthermore, as COVID-19 struck the world at a shocking speed, we faced a situation where the close social networks and agglomeration effects between cities actually threatened humanity.

And that's not all.

Two-thirds of the world's major cities are threatened by rising sea levels due to global warming.

Climate change is relentless and threatens humanity at an increasingly dire and unpredictable level.

But Ben Wilson emphasizes that cities are flexible and ever-changing, and that they have solved the problems they face through various transformations and attempts.

Historically, cities have faced countless crises, including epidemics, pandemics, climate change, and economic cycles, but they have overcome them by evolving rather than succumbing to them.

The author argues that entrepreneurship thrives most in the world's dirtiest and most unsanitary slums.

It is said that this dynamism and challenging spirit of the city are the driving force that has evolved the city.

In this context, he focuses on Lagos, a notorious city in Nigeria, Africa.

The true power of urban evolution is revealed in the case of Otigba Computer Village, Africa's largest information and communications technology market with daily sales exceeding $5 million, thanks to the efforts of a small group of self-taught computer enthusiasts.

Seoul, Songdo… Korea's metropolises

Where does the potential to lead this turbulent century come from?

The preface to the Korean edition of this book includes a detailed account of author Ben Wilson's visit to Songdo.

He also confesses that he could feel the vitality, experimentation, and enthusiastic energy of Korean metropolises, including Seoul, full of the qualities that make people attracted to big city life, and says that this is the incomparably important driving force behind the development of Korean metropolises, which have been at the forefront of global urbanism over the past years.

Humans adapt to living in urban environments and change them to suit their needs.

Cities are human homes, and cities evolve and adapt.

Metropolis provides insight into the essence of human life and activities unfolding within the city's history.

It allows us to look back on the place where we live now and to see where the metropolis, the foundation of human life, is heading.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: March 8, 2021

- Format: Hardcover book binding method guide

- Page count, weight, size: 668 pages | 898g | 152*225*35mm

- ISBN13: 9791164842254

- ISBN10: 1164842250

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)