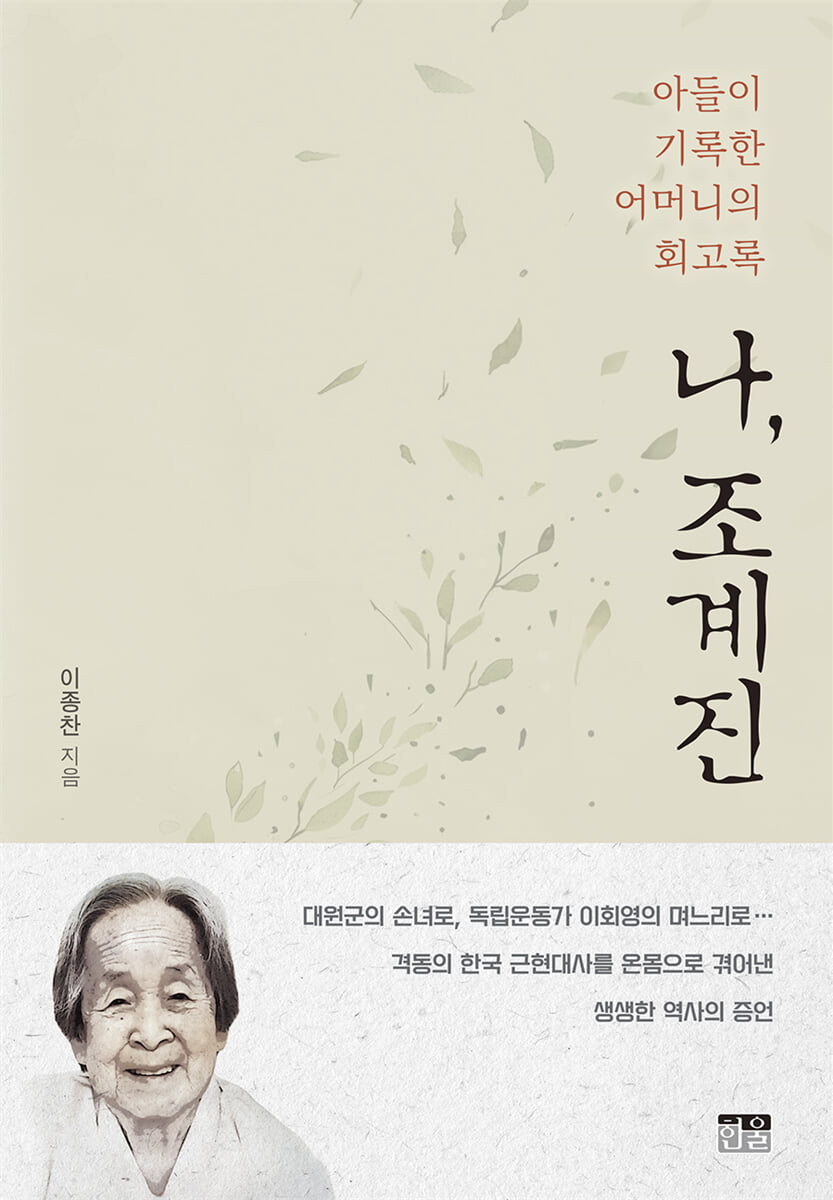

Me, Jo Gye-jin

|

Description

Book Introduction

A mother's memories become her son's writings.

Small fragments of memories convey

The tragedy of the Korean Empire and the story behind the independence movement,

Oh, and your father

There is a family in Korean history that is respected by many as a symbol of noblesse oblige.

This is the family of Udang Lee Hoe-young.

The protagonist of this book, Mrs. Jo Gye-jin, was the daughter-in-law of Udang Lee Hoe-yeong. She was born on June 22, 1897 (May 23, lunar calendar) as the youngest of four sons and one daughter of Lord Jo Jeong-gu and Lady Jeonggyeong of the Wansan Lee clan, daughter of Heungseon Daewongun. She passed away on December 21, 1996.

Born into a royal family in Joseon, a country as volatile as a lantern in the wind, he experienced the ups and downs of Korean history in a family that was a symbol of the independence movement.

For this reason, Mrs. Cho Gye-jin's oral history is also a valuable resource that can fill in the gaps in modern and contemporary Korean history.

This book, which bears witness to the times by transcending daily life and history as a supporting role rather than a leading role, but as the protagonist of a personal story, leaves a deep resonance not only as a meaningful oral history book that serves as a piece of the puzzle of Korean history, but also as a memoir of a woman filled with joys and sorrows.

Lee Jong-chan, the son of Mrs. Jo Gye-jin, who has passed her 90th birthday this year and is the president of the Gwangbokhoe, retraces his mother's life step by step through the unique format of 'A Son's Memoir.'

The life of Mrs. Jo Gye-jin and the deeds of her two fathers (Master Jo Jeong-gu and Mr. Lee Hoe-yeong) form the main and secondary melodies of Sabugok (思父曲), vividly telling the story behind Joseon's tragedy and independence movement.

What would the life of a woman who dreamed of ordinary happiness have been like in a family whose personal history became Korean history?

Small fragments of memories convey

The tragedy of the Korean Empire and the story behind the independence movement,

Oh, and your father

There is a family in Korean history that is respected by many as a symbol of noblesse oblige.

This is the family of Udang Lee Hoe-young.

The protagonist of this book, Mrs. Jo Gye-jin, was the daughter-in-law of Udang Lee Hoe-yeong. She was born on June 22, 1897 (May 23, lunar calendar) as the youngest of four sons and one daughter of Lord Jo Jeong-gu and Lady Jeonggyeong of the Wansan Lee clan, daughter of Heungseon Daewongun. She passed away on December 21, 1996.

Born into a royal family in Joseon, a country as volatile as a lantern in the wind, he experienced the ups and downs of Korean history in a family that was a symbol of the independence movement.

For this reason, Mrs. Cho Gye-jin's oral history is also a valuable resource that can fill in the gaps in modern and contemporary Korean history.

This book, which bears witness to the times by transcending daily life and history as a supporting role rather than a leading role, but as the protagonist of a personal story, leaves a deep resonance not only as a meaningful oral history book that serves as a piece of the puzzle of Korean history, but also as a memoir of a woman filled with joys and sorrows.

Lee Jong-chan, the son of Mrs. Jo Gye-jin, who has passed her 90th birthday this year and is the president of the Gwangbokhoe, retraces his mother's life step by step through the unique format of 'A Son's Memoir.'

The life of Mrs. Jo Gye-jin and the deeds of her two fathers (Master Jo Jeong-gu and Mr. Lee Hoe-yeong) form the main and secondary melodies of Sabugok (思父曲), vividly telling the story behind Joseon's tragedy and independence movement.

What would the life of a woman who dreamed of ordinary happiness have been like in a family whose personal history became Korean history?

index

Part 1: My Family Story

01 Mother's Lonely Last Days

02 My father became a civil servant thanks to my mother.

03 Father resigns from government position

04 In the midst of the Donghak Peasant Revolution and the Sino-Japanese War

05 The Eulmi Incident and King Gojong's Aigwan

06 Independence and self-reliance envisioned by the Russian Embassy

07 The ambitious launch of the Korean Empire, a regrettable failure

08 The Last Road of the Korean Empire

Part 2: The Beginning of the Anti-Japanese Struggle

01 Woodangjang Brothers, Stepping into a New Era

02 Eulsa Treaty and the New People's Association

Movement to nullify the Eulsa Treaty and dispatch of a special envoy to The Hague

04 Iron box secured by Jo Nam-seung under the direction of Emperor Gojong

The 5th Gyeongsul National Shame and Those Who Resisted It

06 My School Life

07 My Marriage and Emperor Gojong's Plan of Exile

08 Groom Lee Kyu-hak's story before his wedding

Part 3: Days in China

01 Beijing, my first place of exile

02 Right now, choose anarchism.

03 Hardships in Beijing

04 A new start in Shanghai!

05 The Last Days of the Udangjang I Know

Part 4: Life Continues, Finally Seeing Liberation

01 Life is born even in the wind and rain

02 New life at home in Poseok-ro

03 People waiting to return home

04 Finally returning home

05 Liberation and Our Home

06 The establishment of the Republic of Korea and the continuing hardships

07 The Korean War I Experienced

Closing the Story: Big Meaning in Small Stories

Chronology of Mrs. Cho Gye-jin

01 Mother's Lonely Last Days

02 My father became a civil servant thanks to my mother.

03 Father resigns from government position

04 In the midst of the Donghak Peasant Revolution and the Sino-Japanese War

05 The Eulmi Incident and King Gojong's Aigwan

06 Independence and self-reliance envisioned by the Russian Embassy

07 The ambitious launch of the Korean Empire, a regrettable failure

08 The Last Road of the Korean Empire

Part 2: The Beginning of the Anti-Japanese Struggle

01 Woodangjang Brothers, Stepping into a New Era

02 Eulsa Treaty and the New People's Association

Movement to nullify the Eulsa Treaty and dispatch of a special envoy to The Hague

04 Iron box secured by Jo Nam-seung under the direction of Emperor Gojong

The 5th Gyeongsul National Shame and Those Who Resisted It

06 My School Life

07 My Marriage and Emperor Gojong's Plan of Exile

08 Groom Lee Kyu-hak's story before his wedding

Part 3: Days in China

01 Beijing, my first place of exile

02 Right now, choose anarchism.

03 Hardships in Beijing

04 A new start in Shanghai!

05 The Last Days of the Udangjang I Know

Part 4: Life Continues, Finally Seeing Liberation

01 Life is born even in the wind and rain

02 New life at home in Poseok-ro

03 People waiting to return home

04 Finally returning home

05 Liberation and Our Home

06 The establishment of the Republic of Korea and the continuing hardships

07 The Korean War I Experienced

Closing the Story: Big Meaning in Small Stories

Chronology of Mrs. Cho Gye-jin

Publisher's Review

A son's song of longing for his mother, a mother's song of longing for her father

The book opens with a painful prelude to the cold of that unusually harsh winter in 1899.

At the end of the century, in the declining Joseon Dynasty, Lady Wansan Lee, the daughter of Heungseon Daewongun and Lady Min of Yeoheung, gave birth to her youngest daughter, Jo Gye-jin, and spent a year and a half in bed before passing away in February of that year.

The story of Jo Gye-jin, the youngest daughter of King Jo Jeong-gu, the last loyal subject of Emperor Gwangmu, begins with her mother's lonely final years.

The girl's dream of having an ordinary family while attending Seungdong Elementary School, Gyeongseong Girls' Elementary School, and Gyeongseong Girls' High School took a completely new turn with her marriage to Lee Gyu-hak, the son of Lee Hoe-young.

Behind the grand history of Joseon's tragedy, exile to China, and Korea's struggle for independence, there were sacrifices made by women who struggled to protect their families while supporting the fighters, avoiding Japanese surveillance.

Jo Gye-jin, too, had to live a difficult life in a foreign land, exposed to the harsh winds of the continent.

During that turbulent time, he lost his two daughters and was in despair.

It was his father, Jo Jeong-gu, who raised Jo Gye-jin, who had given up everything, back up again.

The person who saved me from the depths of despair was, unexpectedly, my father, Lord Jo Jeong-gu.

Although he was usually a strict and reserved person who was difficult to talk to, he became a strength that comforted my despair and consoled my sorrow.

Until then, I didn't know there was such a thing as warm paternal love.

But my father rescued me when I fell into the abyss of sorrow, and I was able to revive by immersing myself in his arms.

Page 491

The author meticulously restores the trajectory of his mother's difficult life, hidden behind the grand flow of Korean history.

At the base of the text, Mrs. Jo Gye-jin's longing, respect, and love for her father, Jo Jeong-gu, flow gently as a quiet song of longing for her father.

Another protagonist,

Lord Jo Jeong-gu and Mr. Lee Hoe-yeong

ㆍMajor Jo Jeong-gu

Jo Jeong-gu was a loyal subject who always stayed by Emperor Gwangmu's side even when he abdicated the throne.

The loyalty of the Jo Jeong-gu family can also be confirmed through the medals awarded by the emperor.

Jo Jeong-gu's sons were involved in forging the royal seal and raising funds through Colbran in connection with the dispatch of the Hague envoy, and after the death of Lee Yong-ik, they not only confirmed the envoy but also worked beyond life and death to publicize the Emperor's (Gojong's) will for independence to the outside world even after the emperor was imprisoned.

After the Japan-Korea Annexation Treaty was signed in 1910, Jo Jeong-gu refused a noble title and a large pension, even choosing death.

On October 7, the Japanese notified his father that they would bestow upon him the title of baron and a monetary reward for his role as Emperor Gojong's brother-in-law, a member of the quasi-royal family, and for having served as Chanjeong of the State Council and Minister of the Imperial Household.

The father trembled in humiliation, saying, “This is an insult to me.”

He tore up the enclosed annexation document and the original document, and left behind a suicide note that said, “Rather than living in shame, let us seek righteousness in death (不可辱而生 寧可義而死),” and then stabbed himself in the neck with a knife in the back room and collapsed.

The butler, Mr. Kim, who was trying to take care of his father, was the first to discover it and screamed.

My older brother wrapped my father, who was covered in blood, in a blanket and took him to the Korean Medical Center by rickshaw.

Page 205

And that's not all.

When he returned to Korea in 1926 to receive treatment for an illness while living in exile, he met with Emperor Yunghui and received his last will and testament, which was published in the Korean-American newspaper Shinhan Minbo on July 8 of that year.

Now I entrust you, the King (Jo Jeong-gu), with proclaiming this decree throughout the country and abroad, so that my people, whom I love and respect most, will clearly know that the annexation was not my doing. Then, the previous so-called decree of approval of the annexation and surrender of the country will be revoked on its own.

Everyone, work hard and achieve liberation.

My soul will help you in the name given to you.

Issue an edict to the governor.

Pages 322-323

ㆍMr. Lee Hoe-young

After the Sampo Incident of 1901, Lee Hoe-young met with Emperor Gwangmu and was appointed as a special envoy to gauge public sentiment, where he played an active role.

Emperor Gwangmu, who received an invitation to the Second International Peace Conference in 1905, secretly ordered Jo Nam-seung to meet with Lee Sang-seol and Lee Hoe-yeong to devise countermeasures when news of the postponed conference in 1906 was announced.

The 'Hague Special Envoy Credentials', which remain a matter of controversy to this day, were entrusted to Lee Hoe-young, who had a unique perspective on the matter, by the New People's Association.

Additionally, Lee Hoe-young, along with Jo Gye-jin's older brothers, plotted for the exile of Emperor Gojong.

However, all plans went up in smoke when the Emperor suddenly passed away.

My father-in-law was a man of great fortune.

… … He was a uniquely hidden revolutionary leader who took non-possession for granted and fought for the impossible with hope.

He valued his comrades more than his children.

Pages 491-492

As this passage says, Lee Hoe-young's last move was a choice made for his comrades.

Li Shizheng and Wu Qihui of the Chinese Nationalist Party proposed to the anarchists that the Chinese Anti-Japanese United Army and Korean resistance forces strengthen their cooperative system in Dongsam Province, which had been vacated by the Manchurian Incident.

Lee Hoi-young volunteered for the dispatch to Dongsamsung.

Please don't draw this time.

I want you to entrust me with this mission.

I have sacrificed many young comrades by sending them to the death.

I'm sixty-six now, I've lived long enough.

I have no regrets even if I die while carrying out my last mission.

Fortunately, I know General Yang Se-bong, who is fighting underground there, very well. And how glorious it would be if we could allied with the Tang Ju-wu Army of China and fight a final battle against the Kwantung Army! I've gotten along well with my comrades there, and Comrade Jang Ki-jun, who is my son-in-law and active in the field, will be able to lend me his support.

Page 349

The unspeakable heartbreaking family story surrounding the death of Lee Hoe-young, whose remains were returned as a meager urn after his arrest, continues.

To avoid spoilers, I hope readers will find and read these passages themselves.

A cool sight to see small fragments of memories!

The Double Helix Story, Peer Review, and Honesty

The greatest strength of this book is that the intricate interweaving of family history and Korean history, like a double helix, creates an immersive experience that makes the book's thickness seem insignificant until the very last page is closed.

Another point to note is that it introduces peer review, which is the evaluation of historical figures by contemporaries within the context and perception of the time, rather than textbook evaluations.

This cool perspective that permeates the book is a unique feature not found in other books, and it further enhances the book's value.

As this book reveals, my mother had strong pride.

Since both her maternal and in-law families were involved in the independence movement, respect for cause and conviction was embodied, and her evaluation of public figures was very clear.

That was the reason why he never tried to meet his cousin, Queen Sunjong, throughout his life.

He despised both his father and uncle, saying they were both 'die-hard pro-Japanese traitors' and that his marriage itself was 'politically motivated'.

Page 15

At that time, what my father especially lamented was the foolishness of Prince Daewongun, who was fooled by the Japanese's tricks.

Unable to eliminate the Minjung War throughout his life, he was so desperate that he borrowed the power of China and even Japan to successfully eliminate the Minjung War.

But that appearance in his later years was extremely ugly.

Page 62

Seo Jae-pil returned to Korea after more than ten years, brought his American wife, and acted like an American, asking to shake hands with the king and sharing a cigarette with him. This angered his father.

“I am an American citizen and cannot hold public office in North Korea.

“Please treat me as a foreign minister.” This advice was also conveyed to the king through an interpreter.

“The fate of the country is at stake, so now I see all sorts of things, haha.” _Page 73

After Yeo Un-hyeong's death, Joo Myeong evaluated him as follows.

"Mongyang was absolutely not a communist! He was not even a true communist, bound by the structure of the Communist Party." "He worked his entire life to realize his ideals as a progressive nationalist, but he achieved nothing and only ruined himself and his family.

“He was a man who lived a busy life.” But I added one more thing to Ju-myeong’s words.

“However, Mr. Mongyang was the only person who understood the difficult life of Udangjang.

Not only that, there was also an aspect of him trying to resemble the life of a bold and unstoppable leader.

“Although they initially argued that a provisional government was necessary, they were also similar in that they did not confine themselves to that framework but acted outside of it.”_Pages 447-448

Seong Jae-jang, concerned that it would be difficult for even Kim Gu to control the irresponsible actions of such a fanatic group, resigned from his key position in the National Assembly, which was formed from the development of the Provisional Government.

In fact, there was great dissatisfaction with President Kim Gu.

I thought it was too short-sighted and had no goals or strategy.

It seemed that he was only focused on opposing the trusteeship and seizing power by mobilizing the provisional government forces, and that he made decisions on the rest on an ad hoc basis.

There are fanatical supporters lining up around you, and their arguments don't always lead to solutions.

Kim Gu was being pulled in that direction.

Pages 453-454

Finally, another strength of this book is its honesty, which does not hide or embellish emotions or thoughts in the face of situations.

Not long after I was comfortably staying at my parents' house, I received an order from my mother-in-law to come immediately and help out.

… … It’s been three days since I arrived. Hakjin’s fever rose all night.

Even cooling my body with a cold towel did not bring down my fever.

There was only one bed, so I laid Hakjin down inside and looked after her. Euljin, who was lying next to me, called out to her sister, “Sister!” and climbed over me to rub our faces together.

From that day on, Euljin also had a fever.

… … When my brother arrived, the two children were already on the verge of death.

My brother took me and my two children to the hospital, but suddenly lost both of them.

I was in a state of utter darkness.

I also fainted and was out of my mind for a while.

Later, Song Dong-daek told me that her brother-in-law yelled at my mother-in-law, “Why did you tell me to come to your in-laws’ house and cause the death of your two children?” and then ran out.

Page 311

Suddenly, the thought, “Where have all the good kids gone?” came to mind and I felt like I was going crazy.

It must have been about three months since I arrived in Seoul.

A letter was sent by messenger from Shanghai.

He apologized for evacuating without prior notice and said he was heartbroken that all the children had died.

I suddenly felt resentful at those words, so I crumpled up the letter and threw it away.

"You're heartbroken? Do you even know the pain I feel? Are you only saying you're heartbroken?" I was furious.

After a while, I picked up the letter again, opened it, and read it again.

“Life in Shanghai is lonely and painful.

The letter ended with a suggestion: “Let’s start over again in Shanghai.”

I had no intention of starting over.

Pages 314-315

I thought that my father-in-law, Woo Dang-jang, was a true pacifist.

He was always a person who thought deeply about something before taking action.

When he was finally leaving, he called me and said:

“When I leave, burn everything in this room.” I had to live with what was left as a national asset, even if it meant defying his orders and hiding and concealing it. Unfortunately, I was unable to do so.

Although I left behind some of the wooden boxes and pavilions that were not easily damaged, I also left behind some orchid paintings, a stack of documents, and a few photographs…

They put everything in the stove and burned it.

Thinking back now, each and every one of those pieces were precious materials that should have been kept, but what can I do about it now?

Page 492

This 496-page book is packed with key moments in Korean history, countless anecdotes that only the author's family could have experienced, and various materials and photos that capture the tragedies of Joseon.

It's not easy to fully capture all of this in a press release.

I simply recommend that you read the book, “I, Jo Gye-jin,” which is a collection of the author’s memories of his mother and all of his experiences overcoming the loss.

The book opens with a painful prelude to the cold of that unusually harsh winter in 1899.

At the end of the century, in the declining Joseon Dynasty, Lady Wansan Lee, the daughter of Heungseon Daewongun and Lady Min of Yeoheung, gave birth to her youngest daughter, Jo Gye-jin, and spent a year and a half in bed before passing away in February of that year.

The story of Jo Gye-jin, the youngest daughter of King Jo Jeong-gu, the last loyal subject of Emperor Gwangmu, begins with her mother's lonely final years.

The girl's dream of having an ordinary family while attending Seungdong Elementary School, Gyeongseong Girls' Elementary School, and Gyeongseong Girls' High School took a completely new turn with her marriage to Lee Gyu-hak, the son of Lee Hoe-young.

Behind the grand history of Joseon's tragedy, exile to China, and Korea's struggle for independence, there were sacrifices made by women who struggled to protect their families while supporting the fighters, avoiding Japanese surveillance.

Jo Gye-jin, too, had to live a difficult life in a foreign land, exposed to the harsh winds of the continent.

During that turbulent time, he lost his two daughters and was in despair.

It was his father, Jo Jeong-gu, who raised Jo Gye-jin, who had given up everything, back up again.

The person who saved me from the depths of despair was, unexpectedly, my father, Lord Jo Jeong-gu.

Although he was usually a strict and reserved person who was difficult to talk to, he became a strength that comforted my despair and consoled my sorrow.

Until then, I didn't know there was such a thing as warm paternal love.

But my father rescued me when I fell into the abyss of sorrow, and I was able to revive by immersing myself in his arms.

Page 491

The author meticulously restores the trajectory of his mother's difficult life, hidden behind the grand flow of Korean history.

At the base of the text, Mrs. Jo Gye-jin's longing, respect, and love for her father, Jo Jeong-gu, flow gently as a quiet song of longing for her father.

Another protagonist,

Lord Jo Jeong-gu and Mr. Lee Hoe-yeong

ㆍMajor Jo Jeong-gu

Jo Jeong-gu was a loyal subject who always stayed by Emperor Gwangmu's side even when he abdicated the throne.

The loyalty of the Jo Jeong-gu family can also be confirmed through the medals awarded by the emperor.

Jo Jeong-gu's sons were involved in forging the royal seal and raising funds through Colbran in connection with the dispatch of the Hague envoy, and after the death of Lee Yong-ik, they not only confirmed the envoy but also worked beyond life and death to publicize the Emperor's (Gojong's) will for independence to the outside world even after the emperor was imprisoned.

After the Japan-Korea Annexation Treaty was signed in 1910, Jo Jeong-gu refused a noble title and a large pension, even choosing death.

On October 7, the Japanese notified his father that they would bestow upon him the title of baron and a monetary reward for his role as Emperor Gojong's brother-in-law, a member of the quasi-royal family, and for having served as Chanjeong of the State Council and Minister of the Imperial Household.

The father trembled in humiliation, saying, “This is an insult to me.”

He tore up the enclosed annexation document and the original document, and left behind a suicide note that said, “Rather than living in shame, let us seek righteousness in death (不可辱而生 寧可義而死),” and then stabbed himself in the neck with a knife in the back room and collapsed.

The butler, Mr. Kim, who was trying to take care of his father, was the first to discover it and screamed.

My older brother wrapped my father, who was covered in blood, in a blanket and took him to the Korean Medical Center by rickshaw.

Page 205

And that's not all.

When he returned to Korea in 1926 to receive treatment for an illness while living in exile, he met with Emperor Yunghui and received his last will and testament, which was published in the Korean-American newspaper Shinhan Minbo on July 8 of that year.

Now I entrust you, the King (Jo Jeong-gu), with proclaiming this decree throughout the country and abroad, so that my people, whom I love and respect most, will clearly know that the annexation was not my doing. Then, the previous so-called decree of approval of the annexation and surrender of the country will be revoked on its own.

Everyone, work hard and achieve liberation.

My soul will help you in the name given to you.

Issue an edict to the governor.

Pages 322-323

ㆍMr. Lee Hoe-young

After the Sampo Incident of 1901, Lee Hoe-young met with Emperor Gwangmu and was appointed as a special envoy to gauge public sentiment, where he played an active role.

Emperor Gwangmu, who received an invitation to the Second International Peace Conference in 1905, secretly ordered Jo Nam-seung to meet with Lee Sang-seol and Lee Hoe-yeong to devise countermeasures when news of the postponed conference in 1906 was announced.

The 'Hague Special Envoy Credentials', which remain a matter of controversy to this day, were entrusted to Lee Hoe-young, who had a unique perspective on the matter, by the New People's Association.

Additionally, Lee Hoe-young, along with Jo Gye-jin's older brothers, plotted for the exile of Emperor Gojong.

However, all plans went up in smoke when the Emperor suddenly passed away.

My father-in-law was a man of great fortune.

… … He was a uniquely hidden revolutionary leader who took non-possession for granted and fought for the impossible with hope.

He valued his comrades more than his children.

Pages 491-492

As this passage says, Lee Hoe-young's last move was a choice made for his comrades.

Li Shizheng and Wu Qihui of the Chinese Nationalist Party proposed to the anarchists that the Chinese Anti-Japanese United Army and Korean resistance forces strengthen their cooperative system in Dongsam Province, which had been vacated by the Manchurian Incident.

Lee Hoi-young volunteered for the dispatch to Dongsamsung.

Please don't draw this time.

I want you to entrust me with this mission.

I have sacrificed many young comrades by sending them to the death.

I'm sixty-six now, I've lived long enough.

I have no regrets even if I die while carrying out my last mission.

Fortunately, I know General Yang Se-bong, who is fighting underground there, very well. And how glorious it would be if we could allied with the Tang Ju-wu Army of China and fight a final battle against the Kwantung Army! I've gotten along well with my comrades there, and Comrade Jang Ki-jun, who is my son-in-law and active in the field, will be able to lend me his support.

Page 349

The unspeakable heartbreaking family story surrounding the death of Lee Hoe-young, whose remains were returned as a meager urn after his arrest, continues.

To avoid spoilers, I hope readers will find and read these passages themselves.

A cool sight to see small fragments of memories!

The Double Helix Story, Peer Review, and Honesty

The greatest strength of this book is that the intricate interweaving of family history and Korean history, like a double helix, creates an immersive experience that makes the book's thickness seem insignificant until the very last page is closed.

Another point to note is that it introduces peer review, which is the evaluation of historical figures by contemporaries within the context and perception of the time, rather than textbook evaluations.

This cool perspective that permeates the book is a unique feature not found in other books, and it further enhances the book's value.

As this book reveals, my mother had strong pride.

Since both her maternal and in-law families were involved in the independence movement, respect for cause and conviction was embodied, and her evaluation of public figures was very clear.

That was the reason why he never tried to meet his cousin, Queen Sunjong, throughout his life.

He despised both his father and uncle, saying they were both 'die-hard pro-Japanese traitors' and that his marriage itself was 'politically motivated'.

Page 15

At that time, what my father especially lamented was the foolishness of Prince Daewongun, who was fooled by the Japanese's tricks.

Unable to eliminate the Minjung War throughout his life, he was so desperate that he borrowed the power of China and even Japan to successfully eliminate the Minjung War.

But that appearance in his later years was extremely ugly.

Page 62

Seo Jae-pil returned to Korea after more than ten years, brought his American wife, and acted like an American, asking to shake hands with the king and sharing a cigarette with him. This angered his father.

“I am an American citizen and cannot hold public office in North Korea.

“Please treat me as a foreign minister.” This advice was also conveyed to the king through an interpreter.

“The fate of the country is at stake, so now I see all sorts of things, haha.” _Page 73

After Yeo Un-hyeong's death, Joo Myeong evaluated him as follows.

"Mongyang was absolutely not a communist! He was not even a true communist, bound by the structure of the Communist Party." "He worked his entire life to realize his ideals as a progressive nationalist, but he achieved nothing and only ruined himself and his family.

“He was a man who lived a busy life.” But I added one more thing to Ju-myeong’s words.

“However, Mr. Mongyang was the only person who understood the difficult life of Udangjang.

Not only that, there was also an aspect of him trying to resemble the life of a bold and unstoppable leader.

“Although they initially argued that a provisional government was necessary, they were also similar in that they did not confine themselves to that framework but acted outside of it.”_Pages 447-448

Seong Jae-jang, concerned that it would be difficult for even Kim Gu to control the irresponsible actions of such a fanatic group, resigned from his key position in the National Assembly, which was formed from the development of the Provisional Government.

In fact, there was great dissatisfaction with President Kim Gu.

I thought it was too short-sighted and had no goals or strategy.

It seemed that he was only focused on opposing the trusteeship and seizing power by mobilizing the provisional government forces, and that he made decisions on the rest on an ad hoc basis.

There are fanatical supporters lining up around you, and their arguments don't always lead to solutions.

Kim Gu was being pulled in that direction.

Pages 453-454

Finally, another strength of this book is its honesty, which does not hide or embellish emotions or thoughts in the face of situations.

Not long after I was comfortably staying at my parents' house, I received an order from my mother-in-law to come immediately and help out.

… … It’s been three days since I arrived. Hakjin’s fever rose all night.

Even cooling my body with a cold towel did not bring down my fever.

There was only one bed, so I laid Hakjin down inside and looked after her. Euljin, who was lying next to me, called out to her sister, “Sister!” and climbed over me to rub our faces together.

From that day on, Euljin also had a fever.

… … When my brother arrived, the two children were already on the verge of death.

My brother took me and my two children to the hospital, but suddenly lost both of them.

I was in a state of utter darkness.

I also fainted and was out of my mind for a while.

Later, Song Dong-daek told me that her brother-in-law yelled at my mother-in-law, “Why did you tell me to come to your in-laws’ house and cause the death of your two children?” and then ran out.

Page 311

Suddenly, the thought, “Where have all the good kids gone?” came to mind and I felt like I was going crazy.

It must have been about three months since I arrived in Seoul.

A letter was sent by messenger from Shanghai.

He apologized for evacuating without prior notice and said he was heartbroken that all the children had died.

I suddenly felt resentful at those words, so I crumpled up the letter and threw it away.

"You're heartbroken? Do you even know the pain I feel? Are you only saying you're heartbroken?" I was furious.

After a while, I picked up the letter again, opened it, and read it again.

“Life in Shanghai is lonely and painful.

The letter ended with a suggestion: “Let’s start over again in Shanghai.”

I had no intention of starting over.

Pages 314-315

I thought that my father-in-law, Woo Dang-jang, was a true pacifist.

He was always a person who thought deeply about something before taking action.

When he was finally leaving, he called me and said:

“When I leave, burn everything in this room.” I had to live with what was left as a national asset, even if it meant defying his orders and hiding and concealing it. Unfortunately, I was unable to do so.

Although I left behind some of the wooden boxes and pavilions that were not easily damaged, I also left behind some orchid paintings, a stack of documents, and a few photographs…

They put everything in the stove and burned it.

Thinking back now, each and every one of those pieces were precious materials that should have been kept, but what can I do about it now?

Page 492

This 496-page book is packed with key moments in Korean history, countless anecdotes that only the author's family could have experienced, and various materials and photos that capture the tragedies of Joseon.

It's not easy to fully capture all of this in a press release.

I simply recommend that you read the book, “I, Jo Gye-jin,” which is a collection of the author’s memories of his mother and all of his experiences overcoming the loss.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: June 22, 2025

- Format: Paperback book binding method guide

- Page count, weight, size: 496 pages | 153*224*15mm

- ISBN13: 9788946083868

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)