A neuroscientist goes to an art museum

|

Description

Book Introduction

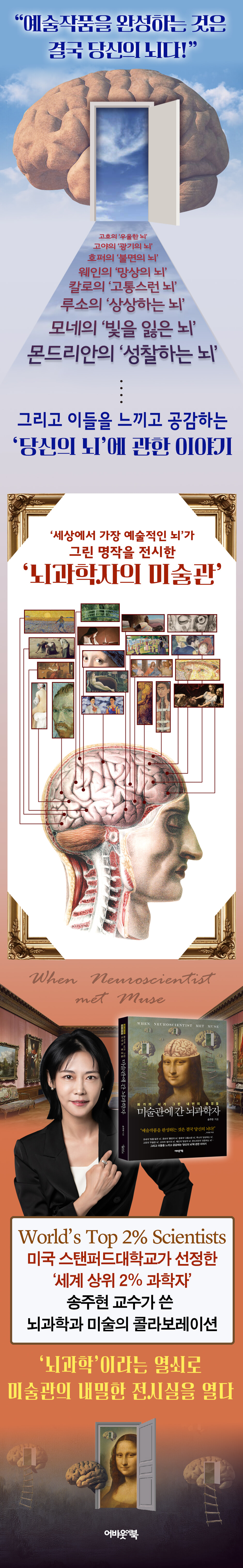

“Ultimately, it is your brain that completes the work of art!”

Monet's "Brain Without Light," Hopper's "Sleepless Brain," Kahlo's "Brain in Pain," and Rousseau's "Imagining Brain."

Van Gogh's 'Melancholic Brain', Goya's 'Mad Brain', Wayne's 'Delusional Brain', Mondrian's 'Reflective Brain'...

And the story about 'your brain' that feels and empathizes with them

How does our brain react when we visit an art museum? Paintings aren't something we see with our eyes, but rather something we appreciate with our brains.

The moment you look at a picture and think it's beautiful, billions of nerve cells are already dancing in your brain.

When an image enters the brain through the visual cortex of the retina, the hippocampus recalls memories, the limbic system generates emotions, and the frontal lobe judges the value of the image as a whole.

For this reason, a painting is like a symphony in which several areas of the brain collaborate.

This book dissects the brains of artists who created great masterpieces, from Rembrandt and Monet, to Kahlo and Kandinsky, to Picasso and Hopper.

In addition, we analyzed the path through which the pictures that entered the viewer's brain caused emotion.

The brain that 'draws' and the brain that 'appreciates' a picture may seem very different, but in fact, they share the common denominator of 'art'.

The moment the switch of 'empathy' is turned on in the appreciating brain, the common denominator is triggered.

This is why Marcel Duchamp, a pioneer of conceptual art, said, “Ultimately, it is the viewer’s brain that completes a work of art.”

This book is a record of the wondrous brain that creates the chemical reaction called 'art' in the minds of artists and viewers.

The reason why Mona Lisa's smile, Van Gogh's starlight, Mondrian's dots, lines, and planes, and Matisse's colored paper make our brains dance is captured in the warp and weft.

Monet's "Brain Without Light," Hopper's "Sleepless Brain," Kahlo's "Brain in Pain," and Rousseau's "Imagining Brain."

Van Gogh's 'Melancholic Brain', Goya's 'Mad Brain', Wayne's 'Delusional Brain', Mondrian's 'Reflective Brain'...

And the story about 'your brain' that feels and empathizes with them

How does our brain react when we visit an art museum? Paintings aren't something we see with our eyes, but rather something we appreciate with our brains.

The moment you look at a picture and think it's beautiful, billions of nerve cells are already dancing in your brain.

When an image enters the brain through the visual cortex of the retina, the hippocampus recalls memories, the limbic system generates emotions, and the frontal lobe judges the value of the image as a whole.

For this reason, a painting is like a symphony in which several areas of the brain collaborate.

This book dissects the brains of artists who created great masterpieces, from Rembrandt and Monet, to Kahlo and Kandinsky, to Picasso and Hopper.

In addition, we analyzed the path through which the pictures that entered the viewer's brain caused emotion.

The brain that 'draws' and the brain that 'appreciates' a picture may seem very different, but in fact, they share the common denominator of 'art'.

The moment the switch of 'empathy' is turned on in the appreciating brain, the common denominator is triggered.

This is why Marcel Duchamp, a pioneer of conceptual art, said, “Ultimately, it is the viewer’s brain that completes a work of art.”

This book is a record of the wondrous brain that creates the chemical reaction called 'art' in the minds of artists and viewers.

The reason why Mona Lisa's smile, Van Gogh's starlight, Mondrian's dots, lines, and planes, and Matisse's colored paper make our brains dance is captured in the warp and weft.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Preface: When Pictures Speak to Your Brain

Chapter 1.

The brain that draws, the brain that appreciates, the brain that analyzes

ㆍThe Painter Who Painted the Colors of Time: Monet's Brain That Lost Its Colors

Masterpieces born with distorted colors: The yellow-tinted brains of Van Gogh and Degas

Artists Who Painted Sound: The Brain of an Artist Who Broke Down the Boundaries of the Senses

Painters Who Painted Smell: The Brains of Painters Who Visualized the Sense of Smell

The Brain of a Dazed Artist: Traces of the Default Mode Network Engraved in Painting

ㆍIn search of art engraved with the brain: Brain anatomy drawn by humanists

The Hidden Mathematical Circuits of the Artist's Brain: Misconceptions and Truths About the Mathematical Brain and the Artistic Brain

Landscapes woven by the artist's brain: Anatomy of the artistic brain

When Your Brain Dances in the Art Museum: The Anatomy of the Appreciative Brain

Chapter 2.

Masterpieces painted by a wounded brain

ㆍDepressive Letters Written on Canvas: The Brains of Depressed Artists

The Art of Madness That Rejects Attunement: The Twisted Brain Circuits Engraved in the Paintings of Schizophrenic Artists

ㆍTheir nights are more beautiful than the days: The brains of artists who painted sleepless nights.

A Portrait of Unbearable Narcissism: The World Dismantled and Reconstructed by the Narcissist's Brain

How a Brain-Crushing Wound Became Art: Paintings Reflecting the Artist's Trauma

Can Art Save an Addicted Life?: The Empty Landscape Painted by an Addicted Brain

Chapter 3: Traces of Neurotransmitters and Hormones Flowing on the Canvas

ㆍWhen the sun shines on your brain, you should look at Renoir's paintings: The magic of neurotransmitters that react to sunlight

ㆍA Portrait of a Mother Who Nurtures the Brain: The Color of Motherhood Created by Oxytocin

Hormones Flowing Through Napoleon's Coronation: Masterpieces Born from the Secretion of Testosterone and Estrogen

A Brain Contemplating in Front of a Gray Canvas: Paintings That Turn On the Switch of Self-Reflection

The brain's survival instinct circuit awakened in front of the Louvre's masterpiece: The truth about the blue brain colored by norepinephrine.

The radiance of women illuminating the autonomic nervous system: the light of serotonin that regulates emotions

The Brain of an Artist Who Painted "Small Happiness": A Art Appreciation Method That Promotes Endorphin Release

The Painter's Brain Trapped in Darkness: Paintings of Madness Caused by Dopamine Overload

Chapter 4: The Aging Brain, Deepening Art, and Timeless Masterpieces

The Artist's Brain Deepens with Age: Brain Aging and Matisse's Later Works

Two Lives, Two Arts, and Two Brains: The Brain Circuits of an Artist Reflecting on the Back Alleys of Life

The Brain of the Artist Who Painted the Greatest Autobiography: Neuroscientific Changes Revealed in Rembrandt's Self-Portraits

The Brain that Carved the 'Aesthetics of the Unfinished': Neuroscientific Implications of Michelangelo's Three Pietas

The brain ages, not degenerates: Cézanne's masterpieces born of predictability and repetition.

Dulled brain nerves, distorted lines and colors: Traces of brain nerve aging shown in the picture.

The Wrinkled Brain That Painted a Great Last Painting: The Strategy Chosen by the Brain of an Old Painter

Chapter 1.

The brain that draws, the brain that appreciates, the brain that analyzes

ㆍThe Painter Who Painted the Colors of Time: Monet's Brain That Lost Its Colors

Masterpieces born with distorted colors: The yellow-tinted brains of Van Gogh and Degas

Artists Who Painted Sound: The Brain of an Artist Who Broke Down the Boundaries of the Senses

Painters Who Painted Smell: The Brains of Painters Who Visualized the Sense of Smell

The Brain of a Dazed Artist: Traces of the Default Mode Network Engraved in Painting

ㆍIn search of art engraved with the brain: Brain anatomy drawn by humanists

The Hidden Mathematical Circuits of the Artist's Brain: Misconceptions and Truths About the Mathematical Brain and the Artistic Brain

Landscapes woven by the artist's brain: Anatomy of the artistic brain

When Your Brain Dances in the Art Museum: The Anatomy of the Appreciative Brain

Chapter 2.

Masterpieces painted by a wounded brain

ㆍDepressive Letters Written on Canvas: The Brains of Depressed Artists

The Art of Madness That Rejects Attunement: The Twisted Brain Circuits Engraved in the Paintings of Schizophrenic Artists

ㆍTheir nights are more beautiful than the days: The brains of artists who painted sleepless nights.

A Portrait of Unbearable Narcissism: The World Dismantled and Reconstructed by the Narcissist's Brain

How a Brain-Crushing Wound Became Art: Paintings Reflecting the Artist's Trauma

Can Art Save an Addicted Life?: The Empty Landscape Painted by an Addicted Brain

Chapter 3: Traces of Neurotransmitters and Hormones Flowing on the Canvas

ㆍWhen the sun shines on your brain, you should look at Renoir's paintings: The magic of neurotransmitters that react to sunlight

ㆍA Portrait of a Mother Who Nurtures the Brain: The Color of Motherhood Created by Oxytocin

Hormones Flowing Through Napoleon's Coronation: Masterpieces Born from the Secretion of Testosterone and Estrogen

A Brain Contemplating in Front of a Gray Canvas: Paintings That Turn On the Switch of Self-Reflection

The brain's survival instinct circuit awakened in front of the Louvre's masterpiece: The truth about the blue brain colored by norepinephrine.

The radiance of women illuminating the autonomic nervous system: the light of serotonin that regulates emotions

The Brain of an Artist Who Painted "Small Happiness": A Art Appreciation Method That Promotes Endorphin Release

The Painter's Brain Trapped in Darkness: Paintings of Madness Caused by Dopamine Overload

Chapter 4: The Aging Brain, Deepening Art, and Timeless Masterpieces

The Artist's Brain Deepens with Age: Brain Aging and Matisse's Later Works

Two Lives, Two Arts, and Two Brains: The Brain Circuits of an Artist Reflecting on the Back Alleys of Life

The Brain of the Artist Who Painted the Greatest Autobiography: Neuroscientific Changes Revealed in Rembrandt's Self-Portraits

The Brain that Carved the 'Aesthetics of the Unfinished': Neuroscientific Implications of Michelangelo's Three Pietas

The brain ages, not degenerates: Cézanne's masterpieces born of predictability and repetition.

Dulled brain nerves, distorted lines and colors: Traces of brain nerve aging shown in the picture.

The Wrinkled Brain That Painted a Great Last Painting: The Strategy Chosen by the Brain of an Old Painter

Detailed image

Into the book

We think we ‘see’ the world with our ‘eyes’.

But in fact, we ‘interpret’ the world with our ‘brain’.

The eyes are merely windows that receive light information.

‘Vision’ is only completed in the brain.

Seeing color is not simply the process of light entering the retina, but the brain interpreting the wavelengths of light.

It is also a work that connects emotions and memories and turns them into a single ‘meaningful image.’

--- From "Monet's Brain that Lost Color"

Kandinsky confessed that he perceived sound as color and imagined sound from color.

These sensory connections are closely related to a phenomenon today called synesthesia.

Synesthesia, called synesthesia in Korean, is a neural response in which one sense stimulates another, such as seeing a color when hearing a sound or recalling a specific sound when seeing a color.

Synesthesia is a concept that has been explored for quite some time.

It is recorded that ancient Greek philosophers such as Plato and Pythagoras examined the relationship between sound and color in the process of discussing the harmony of the senses.

--- From "Painters Who Painted Sound"

Neuroscientifically, the sense of smell is the sense most closely linked to emotion.

Olfactory information is received by olfactory receptors in the nose and transmitted through the olfactory nerve, the first cranial nerve, to the limbic system, which is the brain region that deals with emotions, such as the amygdala and hippocampus.

According to this structure, smells directly evoke memories and emotions in the brain.

Therefore, the smell of blood that we smelled in the past at the hospital is stored deep in the brain and can be easily activated by a similar visual stimulus.

When we see a scene of blood flowing in a painting by Carlo, we think of the smell of blood even though there is no actual smell, because the emotional-olfactory circuitry in our brain is activated.

--- From "The Painter's Brain Visualizing the Sense of Smell"

Rousseau's paintings are mostly centered on primary and flat colors rather than light and shade, and the people and animals are arranged in a dreamy manner without any sense of three-dimensionality.

This reflects a hazy mental state, more like disorganized floating images from a dream than rational thinking in a waking state.

In these scenes where reality and unreality, reason and unconsciousness exist side by side, we experience a sense of familiarity and unfamiliarity occurring simultaneously.

--- From "The Brain of a Dazed Painter"

Hopper's "Nighthawks" is set in a New York cafe late at night.

A glass wall separates the brightly lit interior from the cold street.

People who don't look at each other through glass walls are locking themselves inside themselves.

The image also appears to visualize an overactivated state of the default mode network, which drives self-reflection.

In the deep night, when external stimuli are almost absent, the brain instead questions its own identity and inner feelings more deeply.

--- From "The Brains of Painters Who Painted Sleepless Nights"

Artists' narcissistic tendencies become the driving force behind their creation of their own unique artistic world.

However, if narcissism becomes excessive and you fall into self-intoxication, life becomes creaky.

Picasso and Klimt's art is great, but they did not lead fulfilling lives.

While Picasso and Klimt, like Narcissus, gazed only at their own art reflected in the pond, their families, lovers, and acquaintances must have watched with a pitying heart, like Echo.

This is not limited to Picasso and Klimt.

Would it be too much of a stretch to suggest that Waterhouse's Narcissus overlaps with the countless artists struggling between life and art? --- From "Portrait of an Unbearable Narcissist"

Modigliani's unfortunate life is reflected in his paintings.

Eyes with empty pupils appear as if emotions are blocked.

The distorted body proportions convey the artist's emotional instability.

If drug addiction continues for a long time, the balance of the self-awareness circuitry may be disrupted, which may lead to a dissociative state in which emotions remain but are not connected to self-identity.

This is why in Modigliani's portraits, we can read a state of psychological confusion where the boundary between reality and self is blurred.

--- From "Empty Landscapes Painted by Addicted Brains"

Renoir's colors have an effect that transcends the flatness of paintings hanging on the wall.

It creates the illusion that colors and light spread like air and seep into the viewer's skin.

At that moment, our brains work to not only see, but also walk into the landscape in the painting, enjoying the air, temperature, sounds, and even the sunlight filtering through the leaves.

The colors and shapes in the painting have a kind of experiential effect that shakes and awakens the brain.

The key player here is the 'delusional body'.

--- From "When the sunlight illuminates the brain, one must look at Renoir's paintings"

Historically, eras where testosterone energy was overemphasized were often unfortunate.

This is why David's masterpiece, The Coronation of Napoleon, feels splendid but empty.

The lust for power and the defiant energy that fill the canvas represent the height of a testosterone-fueled world, but there is no breath of empathy or warmth that estrogen creates.

A force that loses its balance is dazzling, but soon vanishes into thin air.

--- From "Hormones Flowing at Napoleon's Coronation"

Some have suggested that El Greco may have had strabismus or double vision.

If the two eyes are not aligned correctly, the visual cortex of the brain may distort perception during the process of combining images, resulting in abnormal depictions of people and landscapes on the screen.

If El Greco's distorted depictions were caused by strabismus or double vision, then the view that his works were Mannerist would be nonsense.

--- From "Dull Brain Nerves, Distorted Lines and Colors"

The Impressionist master, who used to go outside with his easel to capture moments of light, had to return to his studio as his illness worsened.

A respiratory illness confined Pissarro indoors, but his gaze deepened towards the world outside his window.

Although I couldn't breathe the outside air, I was able to observe the world from a new perspective.

The ‘impression’ from the outside has been transformed into ‘depth’ from the inside.

--- From "The Wrinkled Brain that Painted the Great Posthumous Work"

The changes that come with aging aren't necessarily negative.

The 'vertical and horizontal lines and limited colors' adopted by Mondrian simplified the rules of composition by reducing the choices.

This is a strategic choice of the Mondrian brain, which instinctively recognizes the cognitive burden caused by aging and converts it into a simplification of the composition.

It is a trick of creative operation within the brain's operational range without having to make complex design decisions at every moment.

This is a strategy that maximizes artistic value while reducing energy consumption in the brain circuits through simplified formative work.

Just as he directs a performance with a limited range of colored stage lights, Mondrian transformed the vibrant rhythm of New York City with simple combinations of colors and lines in “Broadway Boogie-Woogie.”

In his later years, Mondrian approached his creative work not by 'thinking less', but by becoming less scattered and more condensed.

The 'cognitive deficit' caused by aging was transformed into 'economy of thought' and turned into an artistic asset.

But in fact, we ‘interpret’ the world with our ‘brain’.

The eyes are merely windows that receive light information.

‘Vision’ is only completed in the brain.

Seeing color is not simply the process of light entering the retina, but the brain interpreting the wavelengths of light.

It is also a work that connects emotions and memories and turns them into a single ‘meaningful image.’

--- From "Monet's Brain that Lost Color"

Kandinsky confessed that he perceived sound as color and imagined sound from color.

These sensory connections are closely related to a phenomenon today called synesthesia.

Synesthesia, called synesthesia in Korean, is a neural response in which one sense stimulates another, such as seeing a color when hearing a sound or recalling a specific sound when seeing a color.

Synesthesia is a concept that has been explored for quite some time.

It is recorded that ancient Greek philosophers such as Plato and Pythagoras examined the relationship between sound and color in the process of discussing the harmony of the senses.

--- From "Painters Who Painted Sound"

Neuroscientifically, the sense of smell is the sense most closely linked to emotion.

Olfactory information is received by olfactory receptors in the nose and transmitted through the olfactory nerve, the first cranial nerve, to the limbic system, which is the brain region that deals with emotions, such as the amygdala and hippocampus.

According to this structure, smells directly evoke memories and emotions in the brain.

Therefore, the smell of blood that we smelled in the past at the hospital is stored deep in the brain and can be easily activated by a similar visual stimulus.

When we see a scene of blood flowing in a painting by Carlo, we think of the smell of blood even though there is no actual smell, because the emotional-olfactory circuitry in our brain is activated.

--- From "The Painter's Brain Visualizing the Sense of Smell"

Rousseau's paintings are mostly centered on primary and flat colors rather than light and shade, and the people and animals are arranged in a dreamy manner without any sense of three-dimensionality.

This reflects a hazy mental state, more like disorganized floating images from a dream than rational thinking in a waking state.

In these scenes where reality and unreality, reason and unconsciousness exist side by side, we experience a sense of familiarity and unfamiliarity occurring simultaneously.

--- From "The Brain of a Dazed Painter"

Hopper's "Nighthawks" is set in a New York cafe late at night.

A glass wall separates the brightly lit interior from the cold street.

People who don't look at each other through glass walls are locking themselves inside themselves.

The image also appears to visualize an overactivated state of the default mode network, which drives self-reflection.

In the deep night, when external stimuli are almost absent, the brain instead questions its own identity and inner feelings more deeply.

--- From "The Brains of Painters Who Painted Sleepless Nights"

Artists' narcissistic tendencies become the driving force behind their creation of their own unique artistic world.

However, if narcissism becomes excessive and you fall into self-intoxication, life becomes creaky.

Picasso and Klimt's art is great, but they did not lead fulfilling lives.

While Picasso and Klimt, like Narcissus, gazed only at their own art reflected in the pond, their families, lovers, and acquaintances must have watched with a pitying heart, like Echo.

This is not limited to Picasso and Klimt.

Would it be too much of a stretch to suggest that Waterhouse's Narcissus overlaps with the countless artists struggling between life and art? --- From "Portrait of an Unbearable Narcissist"

Modigliani's unfortunate life is reflected in his paintings.

Eyes with empty pupils appear as if emotions are blocked.

The distorted body proportions convey the artist's emotional instability.

If drug addiction continues for a long time, the balance of the self-awareness circuitry may be disrupted, which may lead to a dissociative state in which emotions remain but are not connected to self-identity.

This is why in Modigliani's portraits, we can read a state of psychological confusion where the boundary between reality and self is blurred.

--- From "Empty Landscapes Painted by Addicted Brains"

Renoir's colors have an effect that transcends the flatness of paintings hanging on the wall.

It creates the illusion that colors and light spread like air and seep into the viewer's skin.

At that moment, our brains work to not only see, but also walk into the landscape in the painting, enjoying the air, temperature, sounds, and even the sunlight filtering through the leaves.

The colors and shapes in the painting have a kind of experiential effect that shakes and awakens the brain.

The key player here is the 'delusional body'.

--- From "When the sunlight illuminates the brain, one must look at Renoir's paintings"

Historically, eras where testosterone energy was overemphasized were often unfortunate.

This is why David's masterpiece, The Coronation of Napoleon, feels splendid but empty.

The lust for power and the defiant energy that fill the canvas represent the height of a testosterone-fueled world, but there is no breath of empathy or warmth that estrogen creates.

A force that loses its balance is dazzling, but soon vanishes into thin air.

--- From "Hormones Flowing at Napoleon's Coronation"

Some have suggested that El Greco may have had strabismus or double vision.

If the two eyes are not aligned correctly, the visual cortex of the brain may distort perception during the process of combining images, resulting in abnormal depictions of people and landscapes on the screen.

If El Greco's distorted depictions were caused by strabismus or double vision, then the view that his works were Mannerist would be nonsense.

--- From "Dull Brain Nerves, Distorted Lines and Colors"

The Impressionist master, who used to go outside with his easel to capture moments of light, had to return to his studio as his illness worsened.

A respiratory illness confined Pissarro indoors, but his gaze deepened towards the world outside his window.

Although I couldn't breathe the outside air, I was able to observe the world from a new perspective.

The ‘impression’ from the outside has been transformed into ‘depth’ from the inside.

--- From "The Wrinkled Brain that Painted the Great Posthumous Work"

The changes that come with aging aren't necessarily negative.

The 'vertical and horizontal lines and limited colors' adopted by Mondrian simplified the rules of composition by reducing the choices.

This is a strategic choice of the Mondrian brain, which instinctively recognizes the cognitive burden caused by aging and converts it into a simplification of the composition.

It is a trick of creative operation within the brain's operational range without having to make complex design decisions at every moment.

This is a strategy that maximizes artistic value while reducing energy consumption in the brain circuits through simplified formative work.

Just as he directs a performance with a limited range of colored stage lights, Mondrian transformed the vibrant rhythm of New York City with simple combinations of colors and lines in “Broadway Boogie-Woogie.”

In his later years, Mondrian approached his creative work not by 'thinking less', but by becoming less scattered and more condensed.

The 'cognitive deficit' caused by aging was transformed into 'economy of thought' and turned into an artistic asset.

--- From "Strategies Chosen by the Brain of an Old Painter"

Publisher's Review

About the brain that draws, the brain that appreciates, and the brain that analyzes

Thirty of the Most Scientific and Artistic Stories

The author of this book is a medical school professor who examines nerve cells (neurons) under a microscope in the laboratory and teaches the structure and function of the brain to medical students in the classroom.

He has continued to achieve academic success, publishing numerous SCI papers related to brain science, and has been recognized internationally for his research achievements, being named several times on the list of 'World's Top 2% Scientists' jointly produced by Stanford University and Elsevier.

The place that such a neuroscientist heads to after leaving the lab is, unexpectedly, an atelier.

The author has been active as a Western painter under the name 'Lee Hyeon' for a long time, and has held 7 solo exhibitions and 6 group exhibitions. He has also won a total of 16 awards in national art competitions, including the National Assembly Culture, Sports and Tourism Committee Chairperson's Award in 2023 and the Silver Prize at the 2024 Republic of Korea Women's Art Exhibition (hosted by the National Veterans Arts and Culture Association).

He is a representative fusion intellectual and 'artientist' who has played two roles as a scientist and an artist.

That's why the author's brain often works between science and art.

For example, the motif of the work is obtained from “Purkinje Neurons of the Cerebellum” (p. 373), in which Santiago Ramon y Cajal, who is called the “father of modern neuroscience,” drew minute nerve cells by hand (Cajal won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1906 for establishing the theory of neurons and precisely visualizing the microscopic structure of nerve cells).

The author is also absorbed in the reaction of the model's frontal lobe and neurotransmitters in the model's head at the moment he draws the model's expression in the studio.

“What is this person thinking and what memories is he recalling right now?”

Sometimes, when I'm drawing a model's face in the studio, I get curious about the 'thoughts' behind his eyes.

The answer lies in your brain.

So some artists began to paint the brain itself, rather than the model's facial expressions.

For them, the brain was not just a biological organ, but a special subject that symbolized the essence of human existence.

Since the Renaissance, the brain has been recognized as more than just an organ that controls bodily functions, but as the center of human identity and self.

Anatomical images of the brain have been incorporated into art.

This is why the Renaissance is a fascinating period for neuroscientists as much as for humanists.” _ From ‘Brain Anatomy Drawn by Humanists’ on page 76

In fact, Leonardo da Vinci drew the “ventricular and sensory pathways inside the skull” (p. 77).

This drawing is considered to have had a great influence on today's neuroanatomy illustration models.

Above all, the brain anatomy diagrams left behind by da Vinci became the catalyst for moving the center of the human mind from the heart to the brain.

Nicolas-Henri Jacob, a disciple of French neoclassical master Jacques-Louis David, drew various anatomical diagrams of the brain for the book "Complete Treatise on Human Anatomy," compiled over 20 years by anatomist Jean-Baptiste Marc Bourgerie, which is now considered a model of "medical art."

The author's brain response becomes even more special when he visits art museums in the US and Europe while taking time out to attend an overseas academic conference.

For example, Monet's 'brain without light' in "Water Lilies" (page 26), Van Gogh's 'melancholic brain' in "Starry Night" (page 139), Hopper's 'sleepless brain' in "Nighthawks" (page 170), and Rembrandt's 'reflective brain' in "Self-Portrait" (page 342) are often captured in the 'author's brain.'

At that moment, the author's mind becomes complicated with all kinds of questions.

'How on earth did Klee's temporal lobe work to make his brushstrokes so rough and crude?', 'What happened to Monet's visual cortex, where colors became red and boundaries blurred?'

In the end, the author searched for materials, read them, made a list, and organized them into writing to solve the unsolvable Möbius strip-like questions on his own.

The writings collected in this way came out of the notebook folder and became this book, “The Neuroscientist Who Went to the Art Museum.”

Opening the Museum's Inner Gallery with the Key of "Brain Science"

This book is divided into four chapters.

The first chapter deals with the honeymoon relationship between brain science and art.

The changes in color and shape in Monet's Rouen Cathedral and Water Lilies series were analyzed through the artist's brain, and synesthesia, or synesthesia, in Kandinsky and Klee's paintings was explained as a 'multi-sensory fusion phenomenon' in neuroscience.

Henri Rousseau's extraordinary imagination introduced the brain's 'default mode network' principle, and Kahlo's painful works dealt with the uncomfortable memories evoked by the sense of smell.

Visual art may seem to have little to do with smell, but that's not the case.

Neuroscientifically, the sense of smell is the sense most closely connected to emotion.

Unlike visual information, olfactory information is transmitted directly to the limbic system, the brain's emotional circuit, through the olfactory bulb without going through the thalamus.

In fact, smells instinctively evoke feelings of discomfort or fear most quickly and strongly.

The motif of Frida Kahlo's painful paintings, such as "Broken Column" and "Henry Ford Hospital," was smell.

The smell of blood, the smell of hospital disinfectant, and the iron in red blood cells' hemoglobin, which were deeply imprinted in the artist's brain at the time of the accident, were projected onto the canvas.

“The scent of a cold air vibrated,” said Carlo, revealing the painful olfactory memory behind the painting.

_ From page 58, ‘Painters Who Painted Smells’

In the second chapter, we explore how brain diseases that plagued artists affected their paintings.

From the depression of Van Gogh and Schiele, the schizophrenia of Wayne and Dadd, the insomnia of Hopper, to the trauma of Caravaggio and Gentileschi, the mental pain that artists paid for their great works was analyzed through neuroscience.

For example, Caravaggio and Gentileschi, who suffered from severe PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder), both painted the biblical Judith Beheading Holofernes, but the Judith in the painting is quite different.

The expression on Judith's face, painted by Gentileschi while she was suffering from the trauma of a terrible sexual assault, is very stern.

On the other hand, Judith painted by Caravaggio is filled with fear and hesitation.

If Gentileschi, as Judith, punished the perpetrator, Caravaggio, who committed murder and was on the run, overlaps with Holofernes, whose head was cut off.

The extreme and self-destructive impulses shown in the picture are a phenomenon that appears in PTSD patients after trauma.

A particularly notable change in the brains of PTSD patients is hyperactivation of the amygdala.

After experiencing trauma, the amygdala becomes hypersensitive to even the slightest stimulus, like a broken alarm.

As seen in Gentileschi's paintings, the hyper-reactivity of the amygdala manifests itself in exaggerated tension and dramatic staging.

_ From page 205, ‘How did the wound that destroyed even the brain become art?’

In the third chapter, neurotransmitters secreted through the brain are applied to various drawings.

These include Renoir's sunlight and melatonin, Cassatt's maternal instinct and oxytocin, Vermeer's happiness and endorphins, Géricault's survival instinct and norepinephrine, Goya's black paintings and dopamine, and David's lust for power and testosterone.

Testosterone is commonly known as a hormone that reveals masculinity, but if we go a step further, it leads to a 'desire for power'.

This is because the paintings of David, a painter who spent his time in scheming during the French Revolution, are heavily imbued with the testosterone of a desire for power.

In "The Coronation of Napoleon," the scene where Napoleon crowns himself is the moment when testosterone reaches its peak.

The action plan designed by the prefrontal cortex, the drive orchestrated by the basal ganglia, and the emotional arousal provided by the amygdala create a scene where the power given to oneself is declared through the interaction of dopamine and testosterone.

_ From page 250, 'Hormones Flowing at Napoleon's Coronation'

The final chapter sheds light on the aging brains of painters and their later works.

As seen in the rough sculptural beauty of Michelangelo's unfinished masterpiece, the Rondanini Pietà, we examined how the slowing of the motor nerves of the great masters as the brain aged was reflected in their works.

Although painters lost the delicate and ornate techniques of their prime in their later years, they learned the value of emptiness and added depth to their works.

This phenomenon is attributed to the brain's selective strategy of converting cognitive deficits into simplicity and repetition, as brain circuits responsible for self-reflection become more active with age.

The masterpieces of elderly masters have proven that brain aging is not necessarily degeneration.

Michelangelo's Rondanini Pietà is the final confession of the brain's emotional circuits, reconfigured by aging.

The statue, which appears to be crushed, is not a being that has not yet awakened from marble.

It is read as a figure permeating a stone, an awareness of the finitude of human life returning to nature.

_ From page 361, ‘The Brain that Carved the Aesthetics of the Unfinished’

|A word from the author|

“The dots, lines, planes, and colors drawn by a painter, and the shapes and textures created by a sculptor are all languages to which the brain reacts most instinctively.

Light, color, space, and shape stimulate the brain's sensory circuits, which in turn trigger emotions, which expand into thoughts, and even lead to actions.

An art museum is not just a place to quietly appreciate paintings.

It is a laboratory that dissects the mysteries of the brain, a library that records human emotions, and at the same time, a room of mirrors that reflects our lives.

This book uses the key of brain science to open the innermost exhibition halls of the art museum, which no one has ever entered before.”

Thirty of the Most Scientific and Artistic Stories

The author of this book is a medical school professor who examines nerve cells (neurons) under a microscope in the laboratory and teaches the structure and function of the brain to medical students in the classroom.

He has continued to achieve academic success, publishing numerous SCI papers related to brain science, and has been recognized internationally for his research achievements, being named several times on the list of 'World's Top 2% Scientists' jointly produced by Stanford University and Elsevier.

The place that such a neuroscientist heads to after leaving the lab is, unexpectedly, an atelier.

The author has been active as a Western painter under the name 'Lee Hyeon' for a long time, and has held 7 solo exhibitions and 6 group exhibitions. He has also won a total of 16 awards in national art competitions, including the National Assembly Culture, Sports and Tourism Committee Chairperson's Award in 2023 and the Silver Prize at the 2024 Republic of Korea Women's Art Exhibition (hosted by the National Veterans Arts and Culture Association).

He is a representative fusion intellectual and 'artientist' who has played two roles as a scientist and an artist.

That's why the author's brain often works between science and art.

For example, the motif of the work is obtained from “Purkinje Neurons of the Cerebellum” (p. 373), in which Santiago Ramon y Cajal, who is called the “father of modern neuroscience,” drew minute nerve cells by hand (Cajal won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1906 for establishing the theory of neurons and precisely visualizing the microscopic structure of nerve cells).

The author is also absorbed in the reaction of the model's frontal lobe and neurotransmitters in the model's head at the moment he draws the model's expression in the studio.

“What is this person thinking and what memories is he recalling right now?”

Sometimes, when I'm drawing a model's face in the studio, I get curious about the 'thoughts' behind his eyes.

The answer lies in your brain.

So some artists began to paint the brain itself, rather than the model's facial expressions.

For them, the brain was not just a biological organ, but a special subject that symbolized the essence of human existence.

Since the Renaissance, the brain has been recognized as more than just an organ that controls bodily functions, but as the center of human identity and self.

Anatomical images of the brain have been incorporated into art.

This is why the Renaissance is a fascinating period for neuroscientists as much as for humanists.” _ From ‘Brain Anatomy Drawn by Humanists’ on page 76

In fact, Leonardo da Vinci drew the “ventricular and sensory pathways inside the skull” (p. 77).

This drawing is considered to have had a great influence on today's neuroanatomy illustration models.

Above all, the brain anatomy diagrams left behind by da Vinci became the catalyst for moving the center of the human mind from the heart to the brain.

Nicolas-Henri Jacob, a disciple of French neoclassical master Jacques-Louis David, drew various anatomical diagrams of the brain for the book "Complete Treatise on Human Anatomy," compiled over 20 years by anatomist Jean-Baptiste Marc Bourgerie, which is now considered a model of "medical art."

The author's brain response becomes even more special when he visits art museums in the US and Europe while taking time out to attend an overseas academic conference.

For example, Monet's 'brain without light' in "Water Lilies" (page 26), Van Gogh's 'melancholic brain' in "Starry Night" (page 139), Hopper's 'sleepless brain' in "Nighthawks" (page 170), and Rembrandt's 'reflective brain' in "Self-Portrait" (page 342) are often captured in the 'author's brain.'

At that moment, the author's mind becomes complicated with all kinds of questions.

'How on earth did Klee's temporal lobe work to make his brushstrokes so rough and crude?', 'What happened to Monet's visual cortex, where colors became red and boundaries blurred?'

In the end, the author searched for materials, read them, made a list, and organized them into writing to solve the unsolvable Möbius strip-like questions on his own.

The writings collected in this way came out of the notebook folder and became this book, “The Neuroscientist Who Went to the Art Museum.”

Opening the Museum's Inner Gallery with the Key of "Brain Science"

This book is divided into four chapters.

The first chapter deals with the honeymoon relationship between brain science and art.

The changes in color and shape in Monet's Rouen Cathedral and Water Lilies series were analyzed through the artist's brain, and synesthesia, or synesthesia, in Kandinsky and Klee's paintings was explained as a 'multi-sensory fusion phenomenon' in neuroscience.

Henri Rousseau's extraordinary imagination introduced the brain's 'default mode network' principle, and Kahlo's painful works dealt with the uncomfortable memories evoked by the sense of smell.

Visual art may seem to have little to do with smell, but that's not the case.

Neuroscientifically, the sense of smell is the sense most closely connected to emotion.

Unlike visual information, olfactory information is transmitted directly to the limbic system, the brain's emotional circuit, through the olfactory bulb without going through the thalamus.

In fact, smells instinctively evoke feelings of discomfort or fear most quickly and strongly.

The motif of Frida Kahlo's painful paintings, such as "Broken Column" and "Henry Ford Hospital," was smell.

The smell of blood, the smell of hospital disinfectant, and the iron in red blood cells' hemoglobin, which were deeply imprinted in the artist's brain at the time of the accident, were projected onto the canvas.

“The scent of a cold air vibrated,” said Carlo, revealing the painful olfactory memory behind the painting.

_ From page 58, ‘Painters Who Painted Smells’

In the second chapter, we explore how brain diseases that plagued artists affected their paintings.

From the depression of Van Gogh and Schiele, the schizophrenia of Wayne and Dadd, the insomnia of Hopper, to the trauma of Caravaggio and Gentileschi, the mental pain that artists paid for their great works was analyzed through neuroscience.

For example, Caravaggio and Gentileschi, who suffered from severe PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder), both painted the biblical Judith Beheading Holofernes, but the Judith in the painting is quite different.

The expression on Judith's face, painted by Gentileschi while she was suffering from the trauma of a terrible sexual assault, is very stern.

On the other hand, Judith painted by Caravaggio is filled with fear and hesitation.

If Gentileschi, as Judith, punished the perpetrator, Caravaggio, who committed murder and was on the run, overlaps with Holofernes, whose head was cut off.

The extreme and self-destructive impulses shown in the picture are a phenomenon that appears in PTSD patients after trauma.

A particularly notable change in the brains of PTSD patients is hyperactivation of the amygdala.

After experiencing trauma, the amygdala becomes hypersensitive to even the slightest stimulus, like a broken alarm.

As seen in Gentileschi's paintings, the hyper-reactivity of the amygdala manifests itself in exaggerated tension and dramatic staging.

_ From page 205, ‘How did the wound that destroyed even the brain become art?’

In the third chapter, neurotransmitters secreted through the brain are applied to various drawings.

These include Renoir's sunlight and melatonin, Cassatt's maternal instinct and oxytocin, Vermeer's happiness and endorphins, Géricault's survival instinct and norepinephrine, Goya's black paintings and dopamine, and David's lust for power and testosterone.

Testosterone is commonly known as a hormone that reveals masculinity, but if we go a step further, it leads to a 'desire for power'.

This is because the paintings of David, a painter who spent his time in scheming during the French Revolution, are heavily imbued with the testosterone of a desire for power.

In "The Coronation of Napoleon," the scene where Napoleon crowns himself is the moment when testosterone reaches its peak.

The action plan designed by the prefrontal cortex, the drive orchestrated by the basal ganglia, and the emotional arousal provided by the amygdala create a scene where the power given to oneself is declared through the interaction of dopamine and testosterone.

_ From page 250, 'Hormones Flowing at Napoleon's Coronation'

The final chapter sheds light on the aging brains of painters and their later works.

As seen in the rough sculptural beauty of Michelangelo's unfinished masterpiece, the Rondanini Pietà, we examined how the slowing of the motor nerves of the great masters as the brain aged was reflected in their works.

Although painters lost the delicate and ornate techniques of their prime in their later years, they learned the value of emptiness and added depth to their works.

This phenomenon is attributed to the brain's selective strategy of converting cognitive deficits into simplicity and repetition, as brain circuits responsible for self-reflection become more active with age.

The masterpieces of elderly masters have proven that brain aging is not necessarily degeneration.

Michelangelo's Rondanini Pietà is the final confession of the brain's emotional circuits, reconfigured by aging.

The statue, which appears to be crushed, is not a being that has not yet awakened from marble.

It is read as a figure permeating a stone, an awareness of the finitude of human life returning to nature.

_ From page 361, ‘The Brain that Carved the Aesthetics of the Unfinished’

|A word from the author|

“The dots, lines, planes, and colors drawn by a painter, and the shapes and textures created by a sculptor are all languages to which the brain reacts most instinctively.

Light, color, space, and shape stimulate the brain's sensory circuits, which in turn trigger emotions, which expand into thoughts, and even lead to actions.

An art museum is not just a place to quietly appreciate paintings.

It is a laboratory that dissects the mysteries of the brain, a library that records human emotions, and at the same time, a room of mirrors that reflects our lives.

This book uses the key of brain science to open the innermost exhibition halls of the art museum, which no one has ever entered before.”

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: December 10, 2025

- Page count, weight, size: 406 pages | 684g | 150*210*20mm

- ISBN13: 9791192229737

- ISBN10: 1192229738

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)