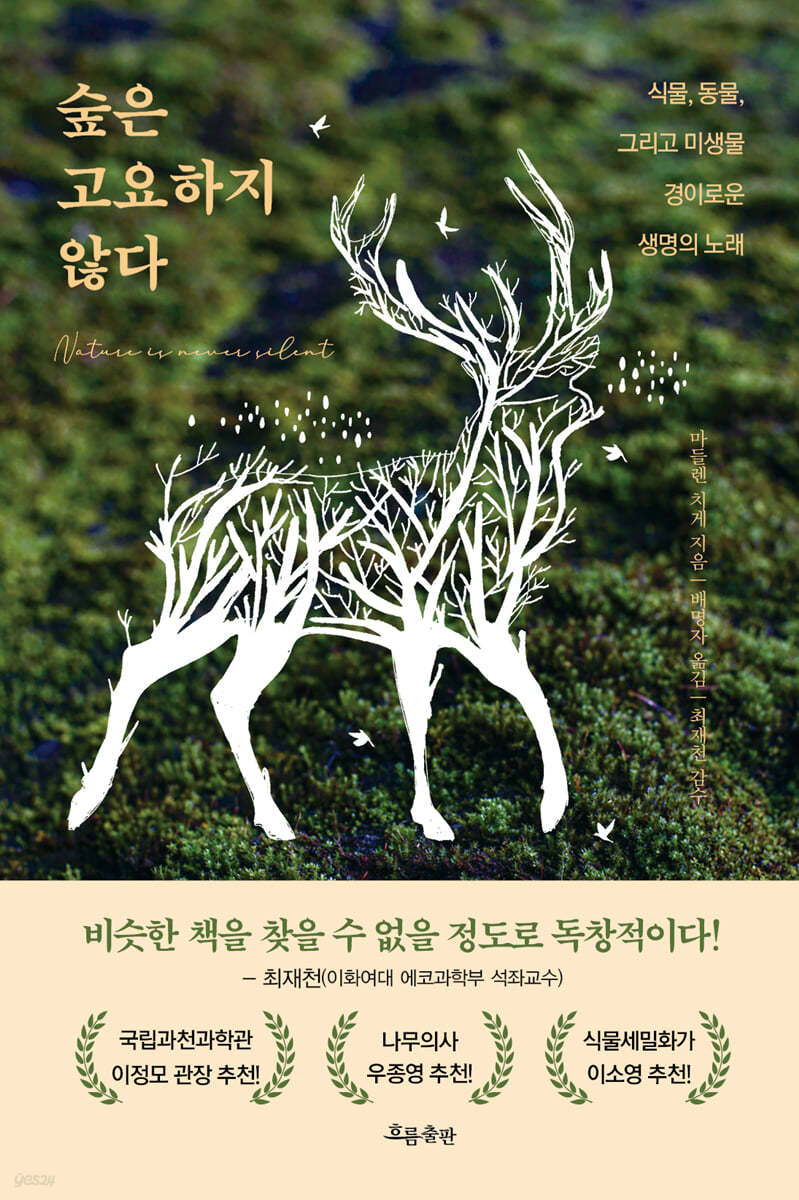

The forest is not quiet

|

Description

Book Introduction

A conversation of nature echoing through the quiet forest! Embrace the joy and wonder of being alive! All animals and plants living on Earth communicate with each other in various ways. So why, how, and with whom do we communicate? Is it true that plants can hear and mushrooms can see? Is boasting and skillful deception a uniquely human trait? It's not. Birds, fish, and even snails, in some ways, are far more adept at communicating than humans. In this book, we encounter the communication skills of some of the most extraordinary creatures, from the Atlantic molly (a fish that gives birth to live young rather than eggs through internal fertilization), to the thrush that transmits codes to deceive its predators, to corn roots that change direction in response to specific frequencies, to rabbits that share information using public toilets, to the planarian that uses cells instead of eyes to receive visual information. Communication is not a human invention. It has connected all life on Earth since the beginning of life. Flowers definitely 'know' that if they send out certain visual signals, they are more likely to be pollinated. This insight into the 'language of nature' will provide us with surprising insights after reading this book. Don't forget. Panta Ray! (Greek for "everything flows") |

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

The forest of the writer's writing should not be quiet.

The Secret of Life

Introduction All life speaks

Part 1: How is information exchanged?

Chapter 1 Life is Transmitting

Colorful and dazzling | Nature's orchestra | A world of smells

Chapter 2 Life is Receiving

Cheers to your eyes | Listen and admire | Always put your olfactory cells first

Part 2: Who, with whom, and why does information exchange occur?

Chapter 3: Single-celled organisms: communication in minimal space

Eat and be eaten | Bacteria eat bacteria

Chapter 4 Multicellular Organisms: The Language of Fungi and Plants

Just a little taste! | Plant defense strategies based on taste | Sexual or asexual reproduction | Love your neighbor

Chapter 5 Multicellular Organisms: Animal-Like Communication

To live or die | You never know when or where something will pop up | Do you want to come this way, or should I go that way? | Two, three, many: Communication in groups

Part 3: What if everything changed?

Chapter 6 When the Animals Left the Forest

The intersection of stock indices and rabbits | The moral of the story?

The Secret of Life

Introduction All life speaks

Part 1: How is information exchanged?

Chapter 1 Life is Transmitting

Colorful and dazzling | Nature's orchestra | A world of smells

Chapter 2 Life is Receiving

Cheers to your eyes | Listen and admire | Always put your olfactory cells first

Part 2: Who, with whom, and why does information exchange occur?

Chapter 3: Single-celled organisms: communication in minimal space

Eat and be eaten | Bacteria eat bacteria

Chapter 4 Multicellular Organisms: The Language of Fungi and Plants

Just a little taste! | Plant defense strategies based on taste | Sexual or asexual reproduction | Love your neighbor

Chapter 5 Multicellular Organisms: Animal-Like Communication

To live or die | You never know when or where something will pop up | Do you want to come this way, or should I go that way? | Two, three, many: Communication in groups

Part 3: What if everything changed?

Chapter 6 When the Animals Left the Forest

The intersection of stock indices and rabbits | The moral of the story?

Detailed image

.jpg)

Into the book

The largest living organism known to date is the underground fungus Armillaria ostoyae.

The mushroom covers more than 950 hectares of wilderness in Oregon, USA – an area larger than 678 football fields.

According to scientists' estimates, this mushroom is as old as 2,400 years.

The smallest living organism, on the other hand, is an archaea called Nanoarchaeum equitans, which is only 350 to 500 nanometers in diameter.

The Latin name roughly translates to 'horse-riding primitive dwarf'.

It's not just a joke name.

This primitive dwarf actually rides around on the 'back' of a single-celled organism called 'Ignicoccus hospitalis'.

Speaking of 'moving around', I'd like to add that the ability to move is another characteristic of life.

Even mushrooms and plants that appear to be motionless at first glance have these characteristics.

--- From "All Life Converses"

Among the Atlantic mollies, some species live in the sunlight outside caves, while others live in the dark inside caves.

Male Atlantic mollies that live outside caves have distinctive orange fins, making them easily distinguishable from the less colorful females.

The Atlantic molly, which lives in a dark cave, lacks this color, proving the adage, “At night, all cats are gray.”

Not only are cave fish colorless, their eyes are also severely degenerated, leaving them with very limited functionality.

The whitish color and degenerate eyes make the cave fish look like ghosts from the underworld.

Cave fish are a striking example of how economical nature is.

Nature either does not produce unnecessary things in the first place or reduces them to suit the situation.

If we can't use the "visible light" channel for communication anyway, why invest time and energy in developing eyes? If there's no phone line at home, what's the use of an expensive phone?

--- From "Life is Receiving"

Arthropods, such as insects, receive sound waves using body parts such as hairs or antennae.

Insect mechanoreceptors vibrate together at different wavelengths depending on the hardness and length of these simple 'receivers'.

For example, most butterflies and moths have body hairs that vibrate at the same wavelength as the auditory information sent by predators.

Even the male mosquito's auditory receptors, located on its antennae, respond only to vibrations produced by the female's flight!

Crickets and cicadas have hearing superior to that of many other insects, equal to the length of their legs.

This is because the so-called 'tympanic organs' are located in their forelimbs.

This tympanic organ is a kind of air sac covered by a membrane, which functions like our eardrum and resonates with pressure changes in the external medium.

The mushroom covers more than 950 hectares of wilderness in Oregon, USA – an area larger than 678 football fields.

According to scientists' estimates, this mushroom is as old as 2,400 years.

The smallest living organism, on the other hand, is an archaea called Nanoarchaeum equitans, which is only 350 to 500 nanometers in diameter.

The Latin name roughly translates to 'horse-riding primitive dwarf'.

It's not just a joke name.

This primitive dwarf actually rides around on the 'back' of a single-celled organism called 'Ignicoccus hospitalis'.

Speaking of 'moving around', I'd like to add that the ability to move is another characteristic of life.

Even mushrooms and plants that appear to be motionless at first glance have these characteristics.

--- From "All Life Converses"

Among the Atlantic mollies, some species live in the sunlight outside caves, while others live in the dark inside caves.

Male Atlantic mollies that live outside caves have distinctive orange fins, making them easily distinguishable from the less colorful females.

The Atlantic molly, which lives in a dark cave, lacks this color, proving the adage, “At night, all cats are gray.”

Not only are cave fish colorless, their eyes are also severely degenerated, leaving them with very limited functionality.

The whitish color and degenerate eyes make the cave fish look like ghosts from the underworld.

Cave fish are a striking example of how economical nature is.

Nature either does not produce unnecessary things in the first place or reduces them to suit the situation.

If we can't use the "visible light" channel for communication anyway, why invest time and energy in developing eyes? If there's no phone line at home, what's the use of an expensive phone?

--- From "Life is Receiving"

Arthropods, such as insects, receive sound waves using body parts such as hairs or antennae.

Insect mechanoreceptors vibrate together at different wavelengths depending on the hardness and length of these simple 'receivers'.

For example, most butterflies and moths have body hairs that vibrate at the same wavelength as the auditory information sent by predators.

Even the male mosquito's auditory receptors, located on its antennae, respond only to vibrations produced by the female's flight!

Crickets and cicadas have hearing superior to that of many other insects, equal to the length of their legs.

This is because the so-called 'tympanic organs' are located in their forelimbs.

This tympanic organ is a kind of air sac covered by a membrane, which functions like our eardrum and resonates with pressure changes in the external medium.

--- From "Life is Receiving"

Publisher's Review

Do you think the forest is quiet?

Then you haven't listened properly yet!

All animals and plants living on Earth communicate with each other in various ways.

So why, how, and with whom do we communicate? Is it true that plants can hear and mushrooms can see? Is boasting and skillful deception a uniquely human trait? It's not.

Birds, fish, and even snails, in some ways, are far more adept at communicating than humans.

Life must know exactly what kind of environment it is surrounded by in order to survive.

Information such as where there is light and water, where to go without tripping over rocks, which way there is food and which way there are predators is directly related to one's survival.

Communication is, of course, essential to obtain this information.

The ecosystem, the large whole to which humans belong, is formed through the intense exchange of information between living things and their interactions with the inanimate environment.

Living things fundamentally use visual information such as color, shape, and movement to communicate, but most non-human creatures, except for chameleons and squid, cannot send signals using visual information.

Therefore, living things have no choice but to communicate in their own unique and very colorful ways.

They use electronic energy or pigments, and even transmit chemical information through smell.

In this book, German female behavioral biologist Madeleine Tschige talks about biocommunication.

Bio, which comes from Greek, means 'life', and communication, which comes from Latin, means 'message'.

Simply put, biocommunication is the 'active transfer of information between living things.'

Humans are no exception when it comes to the need for communication.

Humans always perceive and receive an incalculable amount of environmental information.

However, even if you speak the same language, it can be interpreted in completely different ways depending on the other person, and when that happens, the response to it will also be completely different.

From that perspective, human language cannot be considered accurate.

Compared to the way natural creatures communicate.

Because of this, humans often feel the limitations of information exchange in their daily lives.

Madeleine Chiguet says about this:

The secret of communication between the creatures appearing in this book will be the key to solving it.

In this book, we encounter the communication skills of some of the most extraordinary creatures, from the Atlantic molly (a fish that gives birth to live young rather than eggs through internal fertilization), to the thrush that transmits codes to deceive its predators, to corn roots that change direction in response to specific frequencies, to rabbits that share information using public toilets, to the planarian that uses cells instead of eyes to receive visual information.

From single-celled organisms to fungi, plants, and animals

Nature's orchestra resonates in the quiet forest!

All living things, from single-celled organisms to animals, have receptors that can receive information.

These receptors are used to detect environmental information around their habitat and to exchange information with other organisms.

We capture electrical energy using sensory cells such as light-sensitive eyes, we obtain acoustic information through our ears, and our olfactory cells obtain information from smells.

Life exists everywhere on Earth and under whatever harsh conditions.

Single-celled organisms such as green algae, which cannot photosynthesize on their own, must depend on other organisms for nutrients.

So they sometimes engage in spy-like behavior, such as wiretapping.

Single-celled organisms like paramecium worms are at the top of the diet of many living organisms.

But they too had devised a strategy to avoid being eaten just by sitting there.

The natural enemy of the straw beetle is caught with the 'intent to kill' without even knowing it.

Because they transmit chemical information.

The surface of the paramecium beetle has receptors that detect chemical information from natural enemies.

So these single-celled organisms can react immediately when the scent molecules of their natural enemies hit their receptors.

For example, when a paramecium bug detects the presence of a burrower, it shoots an arrow called a 'trichocyst' in response.

If the scorpion discovers its attacker too late and has already encountered it, it fires this arrow to make a U-turn and retreat.

This escape strategy buys the weevil time.

- From "Eat and Be Eaten"

In situations where survival is threatened, animals can fight, run away, or even play dead, but plants, due to their sessile nature, can only choose to fight.

So plants know how to protect themselves from predators using thorns, toxins, or chemical signals.

Plants also communicate with other plants by sending their roots underground, avoiding human eyes.

The types of chemicals emitted at this time alone are as many as 100.

But their conversations are not always peaceful.

The scaly pine mushroom is a particularly interesting mycorrhizal mushroom from a biocommunication perspective, as it speaks the exact language of its host plant.

The scaly pine mushroom forms a symbiotic relationship with trees in mixed and coniferous forests, and spruce is one of them.

Microbiologists at the University of Jena have discovered that the mushroom produces a chemical called indole-3-acetic acid, just like trees.

Plants also produce this chemical for cell growth.

Matsutake mushrooms release indole-3-acetic acid whenever they want to 'persuade' their tree partners to grow cells.

The more plant cells there are, the more closely the mushrooms can connect with their symbiotic partners, allowing them to consume more nutrients.

- From "Just a Little Taste!"

When it comes to communication habits in living things, spiders are first-class thieves, and fireflies in New Zealand even send out fake light signals to catch prey.

It is well known that whales communicate using ultrasound.

However, among killer whales, groups that prefer prey such as seals, sea lions, and dolphins and groups that prefer salmon show different communication styles.

Prey such as dolphins and sea lions can hear the calls of killer whales from kilometers away.

That's why killer whales that want this kind of food approach by swimming as silently as possible.

It's a completely different communication technique than when hunting salmon, which have poor hearing.

It is by no means easy for living things to survive together in society.

When different living things encounter each other or even share a space, conflict is bound to occur.

For animals, this is a fight over food or a mate.

For communication between living organisms to be considered successful, information must reach the receiving organism accurately, and the information network between living organisms is greatly influenced by the environment.

So what happens when environmental conditions change? A crucial condition for the survival of living organisms is the ability to adapt to a changing environment, which ultimately leads to the ability to evolve.

A new world of biocommunication awakened by science.

“Everything that lives exchanges information!”

Thanks to increasingly accurate scientific methods, humans can now clearly see the world of biocommunication, which was previously unknown to them.

For example, modern humans can now track the reactions of organisms receiving odorant information down to the cellular level.

Natural scientists of the 18th century classified mushrooms as inanimate minerals.

But today we even know that mushrooms have some communication skills!

The best examples we can learn about useful communication from are the creatures that live around us.

Their survival depends on how successfully they communicate and live in harmony with the countless other living beings living in the same space.

Communication reduces 'ignorance' through the sending and receiving of information.

In other words, after having a conversation with someone, you know more than before.

Therefore, through communication with our colleagues, we can gain new information, that is, useful knowledge, and apply it to decisions we face in our daily lives.

Communication is not a human invention.

It has connected all life on Earth since the beginning of life.

Flowers definitely 'know' that if they send out certain visual signals, they are more likely to be pollinated.

This insight into the 'language of nature' will provide us with surprising insights after reading this book.

Don't forget.

Panta Ray! (Greek for "everything flows")

A fascinating book for anyone who wants to maintain a strong connection with life on Earth!

-Umweltnetz-schweiz.ch (Swiss Environmental Foundation)

Madeleine Chigue, a brilliant female biologist, explains in easy-to-understand terms the amazingly clever ways bacteria communicate, how wild rabbits reach agreements, or how badgers use border latrines to warn their mates.

The mushroom sets a trap, the fish lies, and the fox and the fir tree say good night to each other.

Brain food that brightens your mind!

- 《OON (Northern Austrian Newspaper)》

I was captivated at first sight.

The silent conversations between forest friends are surprisingly easy and interesting!

- 《Kurier (Vienna, Austrian local newspaper)》

A book you can read with a smile and admiration!

- 《Radioeins Rbb (Berlin Brandenburg Radio)》

Feminist biologist Madeleine Chiguet explored something surprising.

Read this book.

It's well worth it.

- 《News (German magazine)》

In the forest and in your garden, everything is quiet and peaceful.

Just like Madeleine Chiguet uses her amazing scientific knowledge in a light and fun way.

- 《Kronen Zeitung (Austrian newspaper)》

After this book, communication between animals and plants will be completely reexamined.

- 《ZDF (German public broadcaster)》

Then you haven't listened properly yet!

All animals and plants living on Earth communicate with each other in various ways.

So why, how, and with whom do we communicate? Is it true that plants can hear and mushrooms can see? Is boasting and skillful deception a uniquely human trait? It's not.

Birds, fish, and even snails, in some ways, are far more adept at communicating than humans.

Life must know exactly what kind of environment it is surrounded by in order to survive.

Information such as where there is light and water, where to go without tripping over rocks, which way there is food and which way there are predators is directly related to one's survival.

Communication is, of course, essential to obtain this information.

The ecosystem, the large whole to which humans belong, is formed through the intense exchange of information between living things and their interactions with the inanimate environment.

Living things fundamentally use visual information such as color, shape, and movement to communicate, but most non-human creatures, except for chameleons and squid, cannot send signals using visual information.

Therefore, living things have no choice but to communicate in their own unique and very colorful ways.

They use electronic energy or pigments, and even transmit chemical information through smell.

In this book, German female behavioral biologist Madeleine Tschige talks about biocommunication.

Bio, which comes from Greek, means 'life', and communication, which comes from Latin, means 'message'.

Simply put, biocommunication is the 'active transfer of information between living things.'

Humans are no exception when it comes to the need for communication.

Humans always perceive and receive an incalculable amount of environmental information.

However, even if you speak the same language, it can be interpreted in completely different ways depending on the other person, and when that happens, the response to it will also be completely different.

From that perspective, human language cannot be considered accurate.

Compared to the way natural creatures communicate.

Because of this, humans often feel the limitations of information exchange in their daily lives.

Madeleine Chiguet says about this:

The secret of communication between the creatures appearing in this book will be the key to solving it.

In this book, we encounter the communication skills of some of the most extraordinary creatures, from the Atlantic molly (a fish that gives birth to live young rather than eggs through internal fertilization), to the thrush that transmits codes to deceive its predators, to corn roots that change direction in response to specific frequencies, to rabbits that share information using public toilets, to the planarian that uses cells instead of eyes to receive visual information.

From single-celled organisms to fungi, plants, and animals

Nature's orchestra resonates in the quiet forest!

All living things, from single-celled organisms to animals, have receptors that can receive information.

These receptors are used to detect environmental information around their habitat and to exchange information with other organisms.

We capture electrical energy using sensory cells such as light-sensitive eyes, we obtain acoustic information through our ears, and our olfactory cells obtain information from smells.

Life exists everywhere on Earth and under whatever harsh conditions.

Single-celled organisms such as green algae, which cannot photosynthesize on their own, must depend on other organisms for nutrients.

So they sometimes engage in spy-like behavior, such as wiretapping.

Single-celled organisms like paramecium worms are at the top of the diet of many living organisms.

But they too had devised a strategy to avoid being eaten just by sitting there.

The natural enemy of the straw beetle is caught with the 'intent to kill' without even knowing it.

Because they transmit chemical information.

The surface of the paramecium beetle has receptors that detect chemical information from natural enemies.

So these single-celled organisms can react immediately when the scent molecules of their natural enemies hit their receptors.

For example, when a paramecium bug detects the presence of a burrower, it shoots an arrow called a 'trichocyst' in response.

If the scorpion discovers its attacker too late and has already encountered it, it fires this arrow to make a U-turn and retreat.

This escape strategy buys the weevil time.

- From "Eat and Be Eaten"

In situations where survival is threatened, animals can fight, run away, or even play dead, but plants, due to their sessile nature, can only choose to fight.

So plants know how to protect themselves from predators using thorns, toxins, or chemical signals.

Plants also communicate with other plants by sending their roots underground, avoiding human eyes.

The types of chemicals emitted at this time alone are as many as 100.

But their conversations are not always peaceful.

The scaly pine mushroom is a particularly interesting mycorrhizal mushroom from a biocommunication perspective, as it speaks the exact language of its host plant.

The scaly pine mushroom forms a symbiotic relationship with trees in mixed and coniferous forests, and spruce is one of them.

Microbiologists at the University of Jena have discovered that the mushroom produces a chemical called indole-3-acetic acid, just like trees.

Plants also produce this chemical for cell growth.

Matsutake mushrooms release indole-3-acetic acid whenever they want to 'persuade' their tree partners to grow cells.

The more plant cells there are, the more closely the mushrooms can connect with their symbiotic partners, allowing them to consume more nutrients.

- From "Just a Little Taste!"

When it comes to communication habits in living things, spiders are first-class thieves, and fireflies in New Zealand even send out fake light signals to catch prey.

It is well known that whales communicate using ultrasound.

However, among killer whales, groups that prefer prey such as seals, sea lions, and dolphins and groups that prefer salmon show different communication styles.

Prey such as dolphins and sea lions can hear the calls of killer whales from kilometers away.

That's why killer whales that want this kind of food approach by swimming as silently as possible.

It's a completely different communication technique than when hunting salmon, which have poor hearing.

It is by no means easy for living things to survive together in society.

When different living things encounter each other or even share a space, conflict is bound to occur.

For animals, this is a fight over food or a mate.

For communication between living organisms to be considered successful, information must reach the receiving organism accurately, and the information network between living organisms is greatly influenced by the environment.

So what happens when environmental conditions change? A crucial condition for the survival of living organisms is the ability to adapt to a changing environment, which ultimately leads to the ability to evolve.

A new world of biocommunication awakened by science.

“Everything that lives exchanges information!”

Thanks to increasingly accurate scientific methods, humans can now clearly see the world of biocommunication, which was previously unknown to them.

For example, modern humans can now track the reactions of organisms receiving odorant information down to the cellular level.

Natural scientists of the 18th century classified mushrooms as inanimate minerals.

But today we even know that mushrooms have some communication skills!

The best examples we can learn about useful communication from are the creatures that live around us.

Their survival depends on how successfully they communicate and live in harmony with the countless other living beings living in the same space.

Communication reduces 'ignorance' through the sending and receiving of information.

In other words, after having a conversation with someone, you know more than before.

Therefore, through communication with our colleagues, we can gain new information, that is, useful knowledge, and apply it to decisions we face in our daily lives.

Communication is not a human invention.

It has connected all life on Earth since the beginning of life.

Flowers definitely 'know' that if they send out certain visual signals, they are more likely to be pollinated.

This insight into the 'language of nature' will provide us with surprising insights after reading this book.

Don't forget.

Panta Ray! (Greek for "everything flows")

A fascinating book for anyone who wants to maintain a strong connection with life on Earth!

-Umweltnetz-schweiz.ch (Swiss Environmental Foundation)

Madeleine Chigue, a brilliant female biologist, explains in easy-to-understand terms the amazingly clever ways bacteria communicate, how wild rabbits reach agreements, or how badgers use border latrines to warn their mates.

The mushroom sets a trap, the fish lies, and the fox and the fir tree say good night to each other.

Brain food that brightens your mind!

- 《OON (Northern Austrian Newspaper)》

I was captivated at first sight.

The silent conversations between forest friends are surprisingly easy and interesting!

- 《Kurier (Vienna, Austrian local newspaper)》

A book you can read with a smile and admiration!

- 《Radioeins Rbb (Berlin Brandenburg Radio)》

Feminist biologist Madeleine Chiguet explored something surprising.

Read this book.

It's well worth it.

- 《News (German magazine)》

In the forest and in your garden, everything is quiet and peaceful.

Just like Madeleine Chiguet uses her amazing scientific knowledge in a light and fun way.

- 《Kronen Zeitung (Austrian newspaper)》

After this book, communication between animals and plants will be completely reexamined.

- 《ZDF (German public broadcaster)》

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Publication date: April 23, 2021

- Page count, weight, size: 320 pages | 442g | 140*210*20mm

- ISBN13: 9788965964377

- ISBN 10: 8965964377

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)