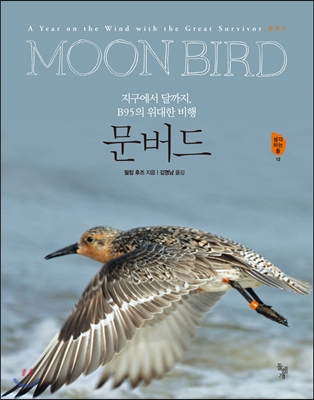

Moonbird

|

Description

Book Introduction

The Unfinished Flight of the Great Survivor B95

A heartwarming nonfiction piece about our "last chance" to prevent extinction.

B95.

Scientists call this bird the 'moonbird'.

This bird, weighing just over 100 grams, survived for an astonishingly long time, flying a distance "enough to fly from Earth to the Moon and back."

Every February, B95 and her companions fly from Tierra del Fuego, at the tip of South America, to the Canadian Arctic to breed, before returning south in late summer.

However, the entire red-breasted rufa, which B95 belongs to, is in danger of disappearing.

This is because the stopping points where the Lupas rest during their long flights are being destroyed by human activities.

During B95's lifetime, the Lupa population declined by a whopping 80 percent.

Now Moonbird is twenty years old and still flying.

Scientists shake their heads and ask.

How could this bird continue its long journey for so long? Will we see the Moonbird again next New Year?

A heartwarming nonfiction piece about our "last chance" to prevent extinction.

B95.

Scientists call this bird the 'moonbird'.

This bird, weighing just over 100 grams, survived for an astonishingly long time, flying a distance "enough to fly from Earth to the Moon and back."

Every February, B95 and her companions fly from Tierra del Fuego, at the tip of South America, to the Canadian Arctic to breed, before returning south in late summer.

However, the entire red-breasted rufa, which B95 belongs to, is in danger of disappearing.

This is because the stopping points where the Lupas rest during their long flights are being destroyed by human activities.

During B95's lifetime, the Lupa population declined by a whopping 80 percent.

Now Moonbird is twenty years old and still flying.

Scientists shake their heads and ask.

How could this bird continue its long journey for so long? Will we see the Moonbird again next New Year?

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Introduction...9

Chapter 1 Superbird...19

Chapter 2 Flying Machines...41

Chapter 3: The Final Battle in Delaware Bay...61

Chapter 4: Catch All...83

Chapter 5: Arctic Breeding Grounds...101

Chapter 6: Mingan, a place to glimpse omens...115

Chapter 7: South, Concluding the Journey...133

Chapter 8: Extinction is Irreversible...151

Character introduction

Clive Minton...38 / Patricia Gonzalez...58 / Brian Harrington 79

Amanda Day...112 / Guy Morrison and Ken Ross...130 / Mike Hudson...165

Appendix: What We Can Do...169

Information about the source...177

References...185

Thanks...191

Recommendation_Yoon Shin-young (Editor-in-Chief of Science Dong-A)...195

Image source...199

Find...200

Chapter 1 Superbird...19

Chapter 2 Flying Machines...41

Chapter 3: The Final Battle in Delaware Bay...61

Chapter 4: Catch All...83

Chapter 5: Arctic Breeding Grounds...101

Chapter 6: Mingan, a place to glimpse omens...115

Chapter 7: South, Concluding the Journey...133

Chapter 8: Extinction is Irreversible...151

Character introduction

Clive Minton...38 / Patricia Gonzalez...58 / Brian Harrington 79

Amanda Day...112 / Guy Morrison and Ken Ross...130 / Mike Hudson...165

Appendix: What We Can Do...169

Information about the source...177

References...185

Thanks...191

Recommendation_Yoon Shin-young (Editor-in-Chief of Science Dong-A)...195

Image source...199

Find...200

Into the book

This bird is B95.

He is the best athlete in the world.

The B95 weighed only 113 grams but flew over 523,000 kilometers in its lifetime.

It's the distance from Earth to the moon and back.

The B95 flies to and from its breeding grounds, using sky routes that have been used since ancient times, as high as mountaintops.

But today, changes to B95's migratory path are causing the superbird to struggle, and the entire rufa subspecies of red-crowned knot to which it belongs is in danger of extinction.

Because B95 and other important places for the herd to rest and refuel, so to speak, stepping stones on their long annual migration routes, are being transformed by human activity.

Can such a place and its food continue to exist? Or will the flights of B95 and the Lupas soon come to an end?

--- p.7

The wind flaps the new feathers.

The chattering flock is on edge as it is time for them to take flight once again.

B95 knows exactly where to go and what to do.

But you never know what awaits you on your way north.

When they arrive in Delaware Bay, starving and hungry, six weeks from now, will they be feasting on horseshoe crab eggs? Will the red tide that once killed so many birds in Uruguay await them? Will a tropical storm sweep across the Atlantic and knock the B95 off course? Will the B95 ever see the Patagonian coast again?

The crowd is in an uproar.

The urge to leave grows uncontrollably.

The red-breasted thrushes fly as one body.

Hundreds of them, in dense formations, their gray and red feathers flashing, spiral together into the clouds as if controlled by a single will.

The birds circle a few times for practice, then soar upward and tilt their bodies toward the north.

It's another flying season for B95 and his crew.

--- p.12~13

“All wild animals’ lives revolve around food,” says Dr. Clive Minton.

“The reason red-breasted waders travel to the Arctic is because there is a huge amount of food there, even if it is only for a few weeks.

The space is also large, allowing each pair to establish its own breeding territory, where they can catch food and feed their young.

Plus, there's light almost all day long, so they can see their prey well.

It's worth taking the risk of moving for that food source.

But by early August, we need to get out of there before winter comes.”

“The red-breasted godwit has learned to forage on beaches all over the world, where the tides rise and fall.

So after mating, most of them return to southern beaches like Tierra del Fuego.

There, they can eat clams and insects buried in the mudflats, and now that it is summer there, the days are long and they can see the food well.”

“If we stop birds from coming to the Southern Hemisphere, the food in the Northern Hemisphere alone won’t be enough.

That's why birds migrate so far.

By migrating so far, the birds maximize the total population of their species.”

--- p.23

Dr. Baker was staring intently at a red-breasted sandpiper, which he held between his thumb and forefinger, his arm outstretched.

“I looked down and saw a black band and a flag with B95 engraved on it, signifying the bird was captured in 1995.

“I couldn’t believe I was holding that thing.” In the twelve years since he first met the bird, Dr. Baker’s hair has turned gray.

But B95 seemed to know no age.

Dr. Baker recalled:

“The bird was in perfect condition.

The weight was just right.

The feathers were also great.

He was as plump as a three-year-old bird.

“The bird in my hand was a superbird.”

The researchers scrambled to their feet and rushed in.

Someone went to get the camera.

Patricia Gonzalez, an expert in feather development, felt guilty about leaving, but couldn't bear it.

Isn't there a moonbird in Dr. Baker's hands?

'Moonbird' was the nickname given to B95 by bird enthusiasts.

Isn't there a veteran who has flown from the bottom of the Earth to the top over thirty times?

But there was something more to it than that.

“The bird was alive,” Gonzalez recalls, his voice choking up even now.

“I was still alive.” (……)

The bird was calmly surrendering itself to Gonzalez's grasp.

Rather, Gonzalez's hands trembled as he worked.

“I kept talking.

I kept telling you.

'I'm sorry, I won't hurt you.

'I'll let you go soon.' The heat from its small body warmed my hand, and the bird's heart was beating very fast.

As I worked, I couldn't help but keep asking myself:

“How can such a fragile life be so strong?”

B95 had lost the original yellow band that was worn under his left leg.

Instead, Gonzalez wore an orange band representing Argentina.

When finished, the bird was left with an orange flag with B95 written on it over its left leg, an orange band under its left leg, and an old black band under its right leg.

Gonzalez stared at the bird for a long moment before letting it go.

How many amazing stories does this bird know! How did this tiny creature survive countless storms? How did it dodge the swooping hawks? And above all, how did it survive so steadfastly, while so many of its friends fell behind?

Patricia Gonzalez knew she had to let the bird go.

Gonzalez adjusted the bands and flags tied to the bird's legs, stretched his hand holding the bird toward the sea, and then opened his hand.

The bird fluttered in the air for a moment, straightening its body, and then quickly regained control of its powerful wings.

And then it turned sharply to the right and flew away.

And so B95 disappeared from everyone's sight.

--- p.32~35

How does the B95 fly so far? The secret lies in its incredible bodybuilding feats.

B95 transforms from an eating machine to a feeding machine in the last few weeks of February and early March.

The process begins with a simple and powerful impulse: 'I must leave now.'

Just in time

Because of the hormones secreted—chemicals that control the activity of cells and organs and direct their actions—B95 becomes increasingly anxious as the amount of light in the sky decreases by the day.

I feel a tingling sensation all over my body as I want to leave for the north.

B95's final destination is a land of tough weeds and faded rocks, about 14,000 kilometers from Patagonia, in the Canadian Arctic.

Right now it's buried in snow and the puddles frozen solid, but by the time B95 arrives—if it succeeds once again—the Arctic will be overflowing with food, color, and light.

There, B95 will find a mate and, with any luck, produce offspring once again.

But this journey is too far to go without stopping in between.

A red-breasted godwit, the size of a magpie, cannot store all the fuel it needs for its journey.

So, to avoid starving, you need to break your journey down into several stages and refuel at stops along the way.

(……)

B95's body gradually swells as it eats without stopping whenever it can find food.

This is because fat is stored in the remaining space and organs throughout the body.

The stomach and digestive system expand to accommodate more fuel.

(A red-breasted sandpiper can eat up to 14 times its body weight.

A person weighing 50 kilograms would have to eat 2,300 300-gram hamburgers with cheese and tomatoes to do that.)

--- p.43~44

B95's father finds a hiding place among the mossy rocks and bushes and digs a hole in the ground.

And fill it with moss and leaves along with your partner.

A few days later, four eggs are laid in the hole.

For the next three weeks, the two birds take turns incubating the eggs, keeping them warm day and night, sharing parental duties.

About three weeks later, in early July, B95 emerges from the eggshell, pecked, pushed, and struggled.

The B95 may stumble at first, but it can do almost anything within a few hours.

In less than a day, they are walking, hunting and eating with their amazing black beaks.

Although it doesn't have flight feathers yet, the soft down covering its entire body keeps it warm.

Within hours of hatching, B95 and her siblings abandon their ground nest and follow their parents across the tundra to a pond.

There they begin to eat insects together with other water birds.

Nature had planned for B95 to become independent quickly.

B95 needs to grow up quickly.

Because just a few days after hatching, the mother flew away in a spiral into the pale sky with other adult females.

The father and other adult males stay behind to keep the young safe and warm in the deep night and protect them from predators.

Danger is everywhere.

Arctic skuas hover over the tundra, always looking to snatch waterfowl eggs and chicks.

There are also white arctic foxes and snowy owls that sneak up and down without making a sound, always nearby.

B95 quickly learned that his father's shrill cry meant 'stay where you are'.

Still unable to fly, B95's only defense is to remain motionless and hope that its mottled feathers will blend in well with the weeds and rocks.

If the fox gets too close, it will sneak up, sniff, and eventually lift its paw to step on B95, but B95's father will fly up in an instant while making a sharp warning sound.

--- p.108~109

Extinction is nature's greatest tragedy.

Extinction means the death of all members of a genetic group.

forever.

Some might argue that what's so tragic about that?

Anyway, according to scientists, during that time

99 percent of all species that have ever lived on Earth are extinct.

Moreover, over the past 500 million years, Earth has experienced five mass extinctions, in which more than two-thirds of all species that ever lived were wiped out in an instant.

The causes ranged from volcanic eruptions to droughts.

The fifth and most recent mass extinction occurred just 65 million years ago.

An asteroid collided with Earth, sending hot dust into the atmosphere, causing the Earth to suddenly become cold and killing off dinosaurs and many other animal species that lived at the time (as we saw earlier, horseshoe crabs survived).

In short, mass extinctions are not a new event.

We have experienced mass extinctions in the past too.

But the sixth wave, which is currently underway, is a little different.

For the first time in history, one species, Homo sapiens, we humans, are wiping out countless life forms by consuming and transforming nearly all of the planet's resources.

Humans currently consume more than half of the Earth's fresh water and nearly half of the products grown on land.

Although humans have only been clearing land and planting crops for a few thousand years, their impact on the planet is so great and accelerating that thousands of plant and animal species are disappearing every year.

According to scientists at the University of California, Berkeley, if the current extinction rate continues, three-quarters of Earth's species could disappear within the next 300 years.

Some of them are famous and beloved, such as the lions of Kenya and the tigers of India, but most are smaller and less noticeable.

He is the best athlete in the world.

The B95 weighed only 113 grams but flew over 523,000 kilometers in its lifetime.

It's the distance from Earth to the moon and back.

The B95 flies to and from its breeding grounds, using sky routes that have been used since ancient times, as high as mountaintops.

But today, changes to B95's migratory path are causing the superbird to struggle, and the entire rufa subspecies of red-crowned knot to which it belongs is in danger of extinction.

Because B95 and other important places for the herd to rest and refuel, so to speak, stepping stones on their long annual migration routes, are being transformed by human activity.

Can such a place and its food continue to exist? Or will the flights of B95 and the Lupas soon come to an end?

--- p.7

The wind flaps the new feathers.

The chattering flock is on edge as it is time for them to take flight once again.

B95 knows exactly where to go and what to do.

But you never know what awaits you on your way north.

When they arrive in Delaware Bay, starving and hungry, six weeks from now, will they be feasting on horseshoe crab eggs? Will the red tide that once killed so many birds in Uruguay await them? Will a tropical storm sweep across the Atlantic and knock the B95 off course? Will the B95 ever see the Patagonian coast again?

The crowd is in an uproar.

The urge to leave grows uncontrollably.

The red-breasted thrushes fly as one body.

Hundreds of them, in dense formations, their gray and red feathers flashing, spiral together into the clouds as if controlled by a single will.

The birds circle a few times for practice, then soar upward and tilt their bodies toward the north.

It's another flying season for B95 and his crew.

--- p.12~13

“All wild animals’ lives revolve around food,” says Dr. Clive Minton.

“The reason red-breasted waders travel to the Arctic is because there is a huge amount of food there, even if it is only for a few weeks.

The space is also large, allowing each pair to establish its own breeding territory, where they can catch food and feed their young.

Plus, there's light almost all day long, so they can see their prey well.

It's worth taking the risk of moving for that food source.

But by early August, we need to get out of there before winter comes.”

“The red-breasted godwit has learned to forage on beaches all over the world, where the tides rise and fall.

So after mating, most of them return to southern beaches like Tierra del Fuego.

There, they can eat clams and insects buried in the mudflats, and now that it is summer there, the days are long and they can see the food well.”

“If we stop birds from coming to the Southern Hemisphere, the food in the Northern Hemisphere alone won’t be enough.

That's why birds migrate so far.

By migrating so far, the birds maximize the total population of their species.”

--- p.23

Dr. Baker was staring intently at a red-breasted sandpiper, which he held between his thumb and forefinger, his arm outstretched.

“I looked down and saw a black band and a flag with B95 engraved on it, signifying the bird was captured in 1995.

“I couldn’t believe I was holding that thing.” In the twelve years since he first met the bird, Dr. Baker’s hair has turned gray.

But B95 seemed to know no age.

Dr. Baker recalled:

“The bird was in perfect condition.

The weight was just right.

The feathers were also great.

He was as plump as a three-year-old bird.

“The bird in my hand was a superbird.”

The researchers scrambled to their feet and rushed in.

Someone went to get the camera.

Patricia Gonzalez, an expert in feather development, felt guilty about leaving, but couldn't bear it.

Isn't there a moonbird in Dr. Baker's hands?

'Moonbird' was the nickname given to B95 by bird enthusiasts.

Isn't there a veteran who has flown from the bottom of the Earth to the top over thirty times?

But there was something more to it than that.

“The bird was alive,” Gonzalez recalls, his voice choking up even now.

“I was still alive.” (……)

The bird was calmly surrendering itself to Gonzalez's grasp.

Rather, Gonzalez's hands trembled as he worked.

“I kept talking.

I kept telling you.

'I'm sorry, I won't hurt you.

'I'll let you go soon.' The heat from its small body warmed my hand, and the bird's heart was beating very fast.

As I worked, I couldn't help but keep asking myself:

“How can such a fragile life be so strong?”

B95 had lost the original yellow band that was worn under his left leg.

Instead, Gonzalez wore an orange band representing Argentina.

When finished, the bird was left with an orange flag with B95 written on it over its left leg, an orange band under its left leg, and an old black band under its right leg.

Gonzalez stared at the bird for a long moment before letting it go.

How many amazing stories does this bird know! How did this tiny creature survive countless storms? How did it dodge the swooping hawks? And above all, how did it survive so steadfastly, while so many of its friends fell behind?

Patricia Gonzalez knew she had to let the bird go.

Gonzalez adjusted the bands and flags tied to the bird's legs, stretched his hand holding the bird toward the sea, and then opened his hand.

The bird fluttered in the air for a moment, straightening its body, and then quickly regained control of its powerful wings.

And then it turned sharply to the right and flew away.

And so B95 disappeared from everyone's sight.

--- p.32~35

How does the B95 fly so far? The secret lies in its incredible bodybuilding feats.

B95 transforms from an eating machine to a feeding machine in the last few weeks of February and early March.

The process begins with a simple and powerful impulse: 'I must leave now.'

Just in time

Because of the hormones secreted—chemicals that control the activity of cells and organs and direct their actions—B95 becomes increasingly anxious as the amount of light in the sky decreases by the day.

I feel a tingling sensation all over my body as I want to leave for the north.

B95's final destination is a land of tough weeds and faded rocks, about 14,000 kilometers from Patagonia, in the Canadian Arctic.

Right now it's buried in snow and the puddles frozen solid, but by the time B95 arrives—if it succeeds once again—the Arctic will be overflowing with food, color, and light.

There, B95 will find a mate and, with any luck, produce offspring once again.

But this journey is too far to go without stopping in between.

A red-breasted godwit, the size of a magpie, cannot store all the fuel it needs for its journey.

So, to avoid starving, you need to break your journey down into several stages and refuel at stops along the way.

(……)

B95's body gradually swells as it eats without stopping whenever it can find food.

This is because fat is stored in the remaining space and organs throughout the body.

The stomach and digestive system expand to accommodate more fuel.

(A red-breasted sandpiper can eat up to 14 times its body weight.

A person weighing 50 kilograms would have to eat 2,300 300-gram hamburgers with cheese and tomatoes to do that.)

--- p.43~44

B95's father finds a hiding place among the mossy rocks and bushes and digs a hole in the ground.

And fill it with moss and leaves along with your partner.

A few days later, four eggs are laid in the hole.

For the next three weeks, the two birds take turns incubating the eggs, keeping them warm day and night, sharing parental duties.

About three weeks later, in early July, B95 emerges from the eggshell, pecked, pushed, and struggled.

The B95 may stumble at first, but it can do almost anything within a few hours.

In less than a day, they are walking, hunting and eating with their amazing black beaks.

Although it doesn't have flight feathers yet, the soft down covering its entire body keeps it warm.

Within hours of hatching, B95 and her siblings abandon their ground nest and follow their parents across the tundra to a pond.

There they begin to eat insects together with other water birds.

Nature had planned for B95 to become independent quickly.

B95 needs to grow up quickly.

Because just a few days after hatching, the mother flew away in a spiral into the pale sky with other adult females.

The father and other adult males stay behind to keep the young safe and warm in the deep night and protect them from predators.

Danger is everywhere.

Arctic skuas hover over the tundra, always looking to snatch waterfowl eggs and chicks.

There are also white arctic foxes and snowy owls that sneak up and down without making a sound, always nearby.

B95 quickly learned that his father's shrill cry meant 'stay where you are'.

Still unable to fly, B95's only defense is to remain motionless and hope that its mottled feathers will blend in well with the weeds and rocks.

If the fox gets too close, it will sneak up, sniff, and eventually lift its paw to step on B95, but B95's father will fly up in an instant while making a sharp warning sound.

--- p.108~109

Extinction is nature's greatest tragedy.

Extinction means the death of all members of a genetic group.

forever.

Some might argue that what's so tragic about that?

Anyway, according to scientists, during that time

99 percent of all species that have ever lived on Earth are extinct.

Moreover, over the past 500 million years, Earth has experienced five mass extinctions, in which more than two-thirds of all species that ever lived were wiped out in an instant.

The causes ranged from volcanic eruptions to droughts.

The fifth and most recent mass extinction occurred just 65 million years ago.

An asteroid collided with Earth, sending hot dust into the atmosphere, causing the Earth to suddenly become cold and killing off dinosaurs and many other animal species that lived at the time (as we saw earlier, horseshoe crabs survived).

In short, mass extinctions are not a new event.

We have experienced mass extinctions in the past too.

But the sixth wave, which is currently underway, is a little different.

For the first time in history, one species, Homo sapiens, we humans, are wiping out countless life forms by consuming and transforming nearly all of the planet's resources.

Humans currently consume more than half of the Earth's fresh water and nearly half of the products grown on land.

Although humans have only been clearing land and planting crops for a few thousand years, their impact on the planet is so great and accelerating that thousands of plant and animal species are disappearing every year.

According to scientists at the University of California, Berkeley, if the current extinction rate continues, three-quarters of Earth's species could disappear within the next 300 years.

Some of them are famous and beloved, such as the lions of Kenya and the tigers of India, but most are smaller and less noticeable.

--- p.153~154

Publisher's Review

“A delightful read for anyone who has ever gazed up at a flock of soaring waterfowl and wondered where they might be going.”

-Carl Heyersen, Newbery Honor-winning author of "Hoot"

B95.

Scientists call this bird the 'moonbird'.

This bird, weighing just over 100 grams, survived for an astonishingly long time, flying a distance "enough to fly from Earth to the Moon and back."

Every February, B95 and her companions fly from Tierra del Fuego, at the tip of South America, to the Canadian Arctic to breed, before returning south in late summer.

However, the entire Red-breasted Stint Lupa, which B95 belongs to, is in danger of disappearing.

This is because the stopping points where the Lupas rest during their long flights are being destroyed by human activities.

During B95's lifetime, the Lupa population declined by a whopping 80 percent.

Even as her comrades disappeared without a trace, Moonbird continued to flap her wings and before she knew it, she was twenty years old.

Scientists shake their heads and ask.

How could this bird continue its long journey for so long? Will we see the Moonbird again next New Year?

Author Philip Huss tells the story of this extraordinary bird, whose long-distance migrations could easily be rewritten several times over, and speaks of "our last chance to prevent extinction."

Of course, the main character of this book is a specific species called the 'Red-breasted Stint Rufa', but what Philip Huss ultimately talks about is 'the tragedy of extinction' itself.

It persuasively explains how devastating and deplorable extinction is, meaning that all members of a genetic group have died out, leaving them irretrievably lost, and appeals to readers to seize the last opportunity before disaster strikes.

Edward O., Professor Emeritus of Harvard University

As Wilson puts it, the book “shows beautifully and captivatingly that by celebrating one individual, we can more easily save the entire species.” Readers will have a wonderful experience flying high alongside the moonbird on its small but resilient wings, contemplating the harsh realities this little bird faces, and ultimately the fate of the planet and the preciousness of life.

This book was published in the United States in 2012.

So, this means that Moonbird was at least twenty years old in 2012, three years ago, and at that point, she was already on an unprecedentedly long ‘flight of a lifetime.’

But surprisingly, the moonbird is still flying in the sky today.

According to a post on the author's website (www.philliphoose.com), just two months ago, in March 2015, a moonbird was again captured on camera by scientists in Tierra del Fuego.

Three years have passed, and now I am twenty-three.

It is indeed a long and 'great flight'.

■ Follow the red-breasted stilt, Rupa, from the bottom of the Earth, Tierra del Fuego, to the top of the Earth, the North Pole

Among the red-breasted godwits, the 'Lupa' species is a 'superbird' that travels 29,000 kilometers round trip from the bottom of the Earth to the top every year.

But since they are not made of steel, they need to make stops along the way to rest their tired bodies and fill their hungry stomachs.

However, due to human activities disrupting the ecology of the port, the Lupas were brought to the brink of extinction in just over a decade.

In 1995, when scientists first banded the young moonbirds, the population was estimated at around 150,000. Starting around 2000, thousands of lupas began dying, and by 2012, fewer than 25,000 remained.

This means that over 80 percent of Moonbird's companions disappeared during his lifetime.

Scientists have determined that sudden environmental changes at stopping points along the birds' massive migrations are the cause of the population decline.

In particular, environmental changes in Delaware Bay, the last stop for the loupas before reaching their breeding grounds, have dealt a fatal blow to the loupas' existence.

The horseshoe crab eggs, a delicacy that the ruffians devoured as soon as they touched down on the ground after taking off from Lagoa do Peixe, Brazil, their second stop, and flying 8,000 kilometers without rest, have been drastically reduced due to overfishing of horseshoe crabs.

Philip Hus, who had already asked questions in his book, "In Search of the White-billed Woodpecker" (tentative title, scheduled to be published by Dolbegae in July), how we should view extinction caused by humans and whether there is any way to prevent it, decided to trace the migratory routes of birds after hearing about the desperate crisis faced by the Lupas and the story of the great survivor, Moonbird, who survived despite it all.

In December 2009, Philippe Huss, not content with simply poring over books and the internet in his studio, flew to Rio Grande, a small town in Tierra del Fuego, Argentina, the wintering ground of the Lupa, to join a multinational group of scientists.

Despite flying a long way to Tierra del Fuego, the "end of the world," where condors soar high and guanacos stare intently, he has traveled only a third of the distance that a red-breasted knot migrates each year.

So Philip Huss diligently flies to the bottom of the Earth to reveal the remarkable ecology of the red-breasted knot, its resilience, the hardships it faces, and the stories of scientists and volunteers from Brazil, Argentina, the United States, and Canada who have joined forces across borders to preserve the red-breasted knot.

After that, he traveled to places like Las Grutas in San Antonio Bay, Argentina, Delaware Bay in the United States, and the Manomet Conservation Science Center in Massachusetts, conducting local research, contributing to migratory bird banding work, and interviewing scientists and environmentalists.

If the main characters of this book are the moonbird and the red-breasted stilt Rufa, the supporting characters are the scientists and environmental activists who sweat to protect them.

Their dedication and passion are vividly captured in the stories Philip Hus wrote through numerous face-to-face meetings, phone calls, and emails.

“When we think of scientists, we think of indoor people in white lab coats, but the scientists I met while writing the book were tough, adventurous people who felt equally at home indoors as outdoors.

They believe that where there are birds, there are discoveries.

If it means traveling to remote places like the top or bottom of the Earth, dragging heavy equipment for long periods of time, banding birds with flashlights in the middle of the night, and trying to set up traps in the fierce wind, they are willing to do it.” (Page 191) In addition to scientists, you can also meet amateurs, especially children and teenagers, who are rolling up their sleeves to conserve the red-breasted knot.

■ Beautiful nonfiction brimming with narrative

Philip Hus is a writer who moves freely across seemingly disparate fields.

However, the areas he enjoys writing about the most and writes about the best are, above all, stories about 'youth social participation' and 'endangered animals'.

If 『The Courage of a Fifteen-Year-Old』, which won the National Book Award and was also loved by Korean readers, is the former, then this book 『Moonbird』 and 『In Search of the White-billed Woodpecker』 (tentative title), which will be published in July, are the latter.

Whatever book he writes, Philip Huss does it himself, poring over mountains of literature, and interviewing experts and stakeholders from a wide range of perspectives. He then weaves together past and present, story and information, into a unique nonfiction.

In this book, Moonbird, Philip Huss tells the story of the life of a small bird called Moonbird in a beautiful and narrative way, based on his characteristically diligent reporting and interviews.

Although it may seem like a simple story about constantly flying, Moonbird's flight and survival are so moving that it makes your nose tingle.

On the one hand, this book is an 'ecological report' and a 'science textbook' that describes the ecology of the Lupa in detail and in an easy-to-understand manner.

The scientific facts are beautifully described in the book, such as why the Lupa migrates such a long distance to the North Pole every year, how they fly such long distances without losing their bearings, how the decline of horseshoe crabs, which seems to have nothing to do with the Lupa, has brought great hardship to the Lupa, and how the newly hatched baby Lupa escapes the threat of predators and grows into a proud adult to continue their species.

It also stands out for its detailed map showing Lupa's movement path at a glance and its abundant use of box descriptions and photos.

The 'Character Introduction' section, which introduces the stories of scientists and environmental activists who are working hard to protect Lupa, is also fascinating.

Philip Huss, who graduated from Yale University's School of Forestry and Environmental Studies and has been an activist for the International Society for Conservation of Nature since 1977, asks at the end of the book, "What good are small waterfowl to us if we can't take them for a walk or feed them?" and then answers as follows.

“Plants and animals help humans live and make their lives better.” But more fundamentally, “all living things are fantastic and mysterious in their own way.”

In other words, the species that live on Earth with us are precious and beautiful in themselves, “just by continuing their lives.”

Losing these precious creatures to extinction forever would be “nature’s greatest tragedy.”

-Carl Heyersen, Newbery Honor-winning author of "Hoot"

B95.

Scientists call this bird the 'moonbird'.

This bird, weighing just over 100 grams, survived for an astonishingly long time, flying a distance "enough to fly from Earth to the Moon and back."

Every February, B95 and her companions fly from Tierra del Fuego, at the tip of South America, to the Canadian Arctic to breed, before returning south in late summer.

However, the entire Red-breasted Stint Lupa, which B95 belongs to, is in danger of disappearing.

This is because the stopping points where the Lupas rest during their long flights are being destroyed by human activities.

During B95's lifetime, the Lupa population declined by a whopping 80 percent.

Even as her comrades disappeared without a trace, Moonbird continued to flap her wings and before she knew it, she was twenty years old.

Scientists shake their heads and ask.

How could this bird continue its long journey for so long? Will we see the Moonbird again next New Year?

Author Philip Huss tells the story of this extraordinary bird, whose long-distance migrations could easily be rewritten several times over, and speaks of "our last chance to prevent extinction."

Of course, the main character of this book is a specific species called the 'Red-breasted Stint Rufa', but what Philip Huss ultimately talks about is 'the tragedy of extinction' itself.

It persuasively explains how devastating and deplorable extinction is, meaning that all members of a genetic group have died out, leaving them irretrievably lost, and appeals to readers to seize the last opportunity before disaster strikes.

Edward O., Professor Emeritus of Harvard University

As Wilson puts it, the book “shows beautifully and captivatingly that by celebrating one individual, we can more easily save the entire species.” Readers will have a wonderful experience flying high alongside the moonbird on its small but resilient wings, contemplating the harsh realities this little bird faces, and ultimately the fate of the planet and the preciousness of life.

This book was published in the United States in 2012.

So, this means that Moonbird was at least twenty years old in 2012, three years ago, and at that point, she was already on an unprecedentedly long ‘flight of a lifetime.’

But surprisingly, the moonbird is still flying in the sky today.

According to a post on the author's website (www.philliphoose.com), just two months ago, in March 2015, a moonbird was again captured on camera by scientists in Tierra del Fuego.

Three years have passed, and now I am twenty-three.

It is indeed a long and 'great flight'.

■ Follow the red-breasted stilt, Rupa, from the bottom of the Earth, Tierra del Fuego, to the top of the Earth, the North Pole

Among the red-breasted godwits, the 'Lupa' species is a 'superbird' that travels 29,000 kilometers round trip from the bottom of the Earth to the top every year.

But since they are not made of steel, they need to make stops along the way to rest their tired bodies and fill their hungry stomachs.

However, due to human activities disrupting the ecology of the port, the Lupas were brought to the brink of extinction in just over a decade.

In 1995, when scientists first banded the young moonbirds, the population was estimated at around 150,000. Starting around 2000, thousands of lupas began dying, and by 2012, fewer than 25,000 remained.

This means that over 80 percent of Moonbird's companions disappeared during his lifetime.

Scientists have determined that sudden environmental changes at stopping points along the birds' massive migrations are the cause of the population decline.

In particular, environmental changes in Delaware Bay, the last stop for the loupas before reaching their breeding grounds, have dealt a fatal blow to the loupas' existence.

The horseshoe crab eggs, a delicacy that the ruffians devoured as soon as they touched down on the ground after taking off from Lagoa do Peixe, Brazil, their second stop, and flying 8,000 kilometers without rest, have been drastically reduced due to overfishing of horseshoe crabs.

Philip Hus, who had already asked questions in his book, "In Search of the White-billed Woodpecker" (tentative title, scheduled to be published by Dolbegae in July), how we should view extinction caused by humans and whether there is any way to prevent it, decided to trace the migratory routes of birds after hearing about the desperate crisis faced by the Lupas and the story of the great survivor, Moonbird, who survived despite it all.

In December 2009, Philippe Huss, not content with simply poring over books and the internet in his studio, flew to Rio Grande, a small town in Tierra del Fuego, Argentina, the wintering ground of the Lupa, to join a multinational group of scientists.

Despite flying a long way to Tierra del Fuego, the "end of the world," where condors soar high and guanacos stare intently, he has traveled only a third of the distance that a red-breasted knot migrates each year.

So Philip Huss diligently flies to the bottom of the Earth to reveal the remarkable ecology of the red-breasted knot, its resilience, the hardships it faces, and the stories of scientists and volunteers from Brazil, Argentina, the United States, and Canada who have joined forces across borders to preserve the red-breasted knot.

After that, he traveled to places like Las Grutas in San Antonio Bay, Argentina, Delaware Bay in the United States, and the Manomet Conservation Science Center in Massachusetts, conducting local research, contributing to migratory bird banding work, and interviewing scientists and environmentalists.

If the main characters of this book are the moonbird and the red-breasted stilt Rufa, the supporting characters are the scientists and environmental activists who sweat to protect them.

Their dedication and passion are vividly captured in the stories Philip Hus wrote through numerous face-to-face meetings, phone calls, and emails.

“When we think of scientists, we think of indoor people in white lab coats, but the scientists I met while writing the book were tough, adventurous people who felt equally at home indoors as outdoors.

They believe that where there are birds, there are discoveries.

If it means traveling to remote places like the top or bottom of the Earth, dragging heavy equipment for long periods of time, banding birds with flashlights in the middle of the night, and trying to set up traps in the fierce wind, they are willing to do it.” (Page 191) In addition to scientists, you can also meet amateurs, especially children and teenagers, who are rolling up their sleeves to conserve the red-breasted knot.

■ Beautiful nonfiction brimming with narrative

Philip Hus is a writer who moves freely across seemingly disparate fields.

However, the areas he enjoys writing about the most and writes about the best are, above all, stories about 'youth social participation' and 'endangered animals'.

If 『The Courage of a Fifteen-Year-Old』, which won the National Book Award and was also loved by Korean readers, is the former, then this book 『Moonbird』 and 『In Search of the White-billed Woodpecker』 (tentative title), which will be published in July, are the latter.

Whatever book he writes, Philip Huss does it himself, poring over mountains of literature, and interviewing experts and stakeholders from a wide range of perspectives. He then weaves together past and present, story and information, into a unique nonfiction.

In this book, Moonbird, Philip Huss tells the story of the life of a small bird called Moonbird in a beautiful and narrative way, based on his characteristically diligent reporting and interviews.

Although it may seem like a simple story about constantly flying, Moonbird's flight and survival are so moving that it makes your nose tingle.

On the one hand, this book is an 'ecological report' and a 'science textbook' that describes the ecology of the Lupa in detail and in an easy-to-understand manner.

The scientific facts are beautifully described in the book, such as why the Lupa migrates such a long distance to the North Pole every year, how they fly such long distances without losing their bearings, how the decline of horseshoe crabs, which seems to have nothing to do with the Lupa, has brought great hardship to the Lupa, and how the newly hatched baby Lupa escapes the threat of predators and grows into a proud adult to continue their species.

It also stands out for its detailed map showing Lupa's movement path at a glance and its abundant use of box descriptions and photos.

The 'Character Introduction' section, which introduces the stories of scientists and environmental activists who are working hard to protect Lupa, is also fascinating.

Philip Huss, who graduated from Yale University's School of Forestry and Environmental Studies and has been an activist for the International Society for Conservation of Nature since 1977, asks at the end of the book, "What good are small waterfowl to us if we can't take them for a walk or feed them?" and then answers as follows.

“Plants and animals help humans live and make their lives better.” But more fundamentally, “all living things are fantastic and mysterious in their own way.”

In other words, the species that live on Earth with us are precious and beautiful in themselves, “just by continuing their lives.”

Losing these precious creatures to extinction forever would be “nature’s greatest tragedy.”

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of publication: May 18, 2015

- Page count, weight, size: 204 pages | 474g | 180*230*13mm

- ISBN13: 9788971996584

- ISBN10: 8971996587

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)