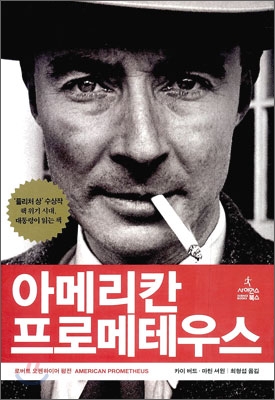

American Prometheus

|

Description

Book Introduction

Father of the atomic bomb,

The Epic of Robert Oppenheimer's Glory and Fall

Nuclear weapons, born in the race to win World War II, have literally become 'bombs' due to their enormous destructive power and potential for abuse immediately after their birth.

It also brought about dramatic moments in the life of Oppenheimer, the director of the Manhattan Project that developed the atomic bomb and the 'father of the atomic bomb'.

『American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J.

Robert Oppenheimer) is the definitive biography of Oppenheimer, written by two authors, journalist Kai Bird and Martin Sherwin, professor of English literature and American history, after 25 years of research, interviews, and reading FBI documents.

This book is largely divided into five parts.

Part 1 shows Oppenheimer's family history, childhood, and his development as a physicist, while Part 2 examines Oppenheimer's long-term lover and wife, as well as the encounters that changed his life.

Part 3 depicts Oppenheimer's activities as the general director of the Manhattan Project and the moment of success of the Trinity atomic bomb test, while Part 4 focuses on his changed state of mind and position following the dropping of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima.

Part 5 covers Oppenheimer's later years, including his humiliation and resignation from the security hearings that were intertwined with McCarthyism.

Through the life of Robert Oppenheimer, the father of the atomic bomb, we can shed new light on the modern era of nuclear crisis.

The Epic of Robert Oppenheimer's Glory and Fall

Nuclear weapons, born in the race to win World War II, have literally become 'bombs' due to their enormous destructive power and potential for abuse immediately after their birth.

It also brought about dramatic moments in the life of Oppenheimer, the director of the Manhattan Project that developed the atomic bomb and the 'father of the atomic bomb'.

『American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J.

Robert Oppenheimer) is the definitive biography of Oppenheimer, written by two authors, journalist Kai Bird and Martin Sherwin, professor of English literature and American history, after 25 years of research, interviews, and reading FBI documents.

This book is largely divided into five parts.

Part 1 shows Oppenheimer's family history, childhood, and his development as a physicist, while Part 2 examines Oppenheimer's long-term lover and wife, as well as the encounters that changed his life.

Part 3 depicts Oppenheimer's activities as the general director of the Manhattan Project and the moment of success of the Trinity atomic bomb test, while Part 4 focuses on his changed state of mind and position following the dropping of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima.

Part 5 covers Oppenheimer's later years, including his humiliation and resignation from the security hearings that were intertwined with McCarthyism.

Through the life of Robert Oppenheimer, the father of the atomic bomb, we can shed new light on the modern era of nuclear crisis.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Preface to the Korean edition / Preface / Prologue

Part 1

Chapter 1 He accepted every new idea as something perfectly beautiful / Chapter 2 His own prison / Chapter 3 It's not really fun / Chapter 4 The work here is, thankfully, difficult but fun / Chapter 5 I am Oppenheimer / Chapter 6 Oppi / Chapter 7 The Nim Nim Boys

Part 2

Chapter 8: My Interests Began to Shift in 1936 / Chapter 9: Frank Cut It Out and Sent It / Chapter 10: More and More Certainly / Chapter 11: Steve, I'm Marrying Your Friend / Chapter 12: We Were Pulling the New Deal Left / Chapter 13: The High-Speed Split Coordinator / Chapter 14: The Chevalier Affair

Part 3

Chapter 15 He Became a Great Patriot / Chapter 16 Too Many Secrets / Chapter 17 Oppenheimer Is Telling the Truth / Chapter 18 A Suicide with Unclear Motives / Chapter 19 Would You Consider Adopting Her? / Chapter 20 If Bohr Was God, Opie Was His Prophet / Chapter 21 How Apparatus Affects Civilization / Chapter 22 Now We Are All Bastards

Part 4

Chapter 23 The Poor People / Chapter 24 I Feel Blood on My Hands / Chapter 25 Someone Might Destroy New York / Chapter 26 Opie Had a Pimple, But Now She's Immune / Chapter 27 The Hotel for Intellectuals / Chapter 28 He Couldn't Understand Why He Did It / Chapter 29 That's Why She Thrown Things at Him / Chapter 30 He Knew Nothing About His Opinion / Chapter 31 Dark Words About Opie / Chapter 32 Scientist X / Chapter 33 The Beast in the Jungle

Part 5

Chapter 34 Things Don't Look So Good, Do They? / Chapter 35 I'm Afraid This Is All Stupid / Chapter 36 Signs of Hysteria / Chapter 37 The Infamy of This Country / Chapter 38 I Can Still Feel the Hot Blood on My Hands / Chapter 39 It Was a Utopia / Chapter 40 It Should Have Been Done the Day After Trinity

Epilogue / Acknowledgments / Original Source / References / Translator's Note / Index / Photo Sources

Part 1

Chapter 1 He accepted every new idea as something perfectly beautiful / Chapter 2 His own prison / Chapter 3 It's not really fun / Chapter 4 The work here is, thankfully, difficult but fun / Chapter 5 I am Oppenheimer / Chapter 6 Oppi / Chapter 7 The Nim Nim Boys

Part 2

Chapter 8: My Interests Began to Shift in 1936 / Chapter 9: Frank Cut It Out and Sent It / Chapter 10: More and More Certainly / Chapter 11: Steve, I'm Marrying Your Friend / Chapter 12: We Were Pulling the New Deal Left / Chapter 13: The High-Speed Split Coordinator / Chapter 14: The Chevalier Affair

Part 3

Chapter 15 He Became a Great Patriot / Chapter 16 Too Many Secrets / Chapter 17 Oppenheimer Is Telling the Truth / Chapter 18 A Suicide with Unclear Motives / Chapter 19 Would You Consider Adopting Her? / Chapter 20 If Bohr Was God, Opie Was His Prophet / Chapter 21 How Apparatus Affects Civilization / Chapter 22 Now We Are All Bastards

Part 4

Chapter 23 The Poor People / Chapter 24 I Feel Blood on My Hands / Chapter 25 Someone Might Destroy New York / Chapter 26 Opie Had a Pimple, But Now She's Immune / Chapter 27 The Hotel for Intellectuals / Chapter 28 He Couldn't Understand Why He Did It / Chapter 29 That's Why She Thrown Things at Him / Chapter 30 He Knew Nothing About His Opinion / Chapter 31 Dark Words About Opie / Chapter 32 Scientist X / Chapter 33 The Beast in the Jungle

Part 5

Chapter 34 Things Don't Look So Good, Do They? / Chapter 35 I'm Afraid This Is All Stupid / Chapter 36 Signs of Hysteria / Chapter 37 The Infamy of This Country / Chapter 38 I Can Still Feel the Hot Blood on My Hands / Chapter 39 It Was a Utopia / Chapter 40 It Should Have Been Done the Day After Trinity

Epilogue / Acknowledgments / Original Source / References / Translator's Note / Index / Photo Sources

Publisher's Review

Winner of the 2005 National Book Critics Circle Award and the 2006 Pulitzer Prize!

The Life of Robert Oppenheimer, Father of the Atomic Bomb

Rereading Oppenheimer in the Age of Nuclear Crisis

If a nation isolated from the mainstream of international science, culture, and commerce, and even failing to feed its own people, can produce nuclear weapons, it clearly shows that the global proliferation of nuclear weapons is not so difficult. —Kai Bird and Martin Sherwin, Preface to the Korean Edition

A statement released at the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) Ministerial Meeting held in Hanoi, Vietnam on July 24th called for the resumption of the six-party talks on North Korea's nuclear program.

Despite its commitment to denuclearization at the 2005 Six-Party Talks, North Korea conducted nuclear tests using enriched plutonium in 2006 and 2009, and announced in May that it had successfully achieved a nuclear fusion reaction.

And, by refusing to give up its nuclear facilities to counter financial sanctions against various provocations, it is heightening tensions in the international community.

This situation was predicted as early as the last century, when nuclear weapons were first created.

And in our country, where this sharp conflict is currently ongoing, the person who deserves attention is Robert Oppenheimer.

Nuclear weapons, born in the race to win World War II, have literally become 'bombs' due to their enormous destructive power and potential for abuse immediately after their birth.

It also brought about dramatic moments in the life of Oppenheimer, the director of the Manhattan Project that developed the atomic bomb and the 'father of the atomic bomb'.

This time, 『American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J.

Robert Oppenheimer) is the definitive biography of Oppenheimer, written by two authors, journalist Kai Bird and Martin Sherwin, professor of English literature and American history, after 25 years of research, interviews, and reading FBI documents.

Upon its publication in 2005, American Prometheus won the National Book Critics Circle (NBCC) Award for Biography and the Pulitzer Prize for Biography or Autobiography in 2006.

Knowledge itself is the foundation of civilization.

But broadening the scope of knowledge places greater responsibility on individuals and nations through the possibility of shaping the conditions of human life. — Niels Bohr

The Life of Oppenheimer, America's Prometheus

Prometheus, a character in Greek mythology, stole fire from Zeus and gave it to humans, and was punished by having an eagle peck out his liver every day.

As Scientific Monthly wrote after the Hiroshima atomic bombing, “The modern Prometheus has once again stormed Mount Olympus, bringing back Zeus’ thunderbolts for humanity,” the scientists who participated in the Manhattan Project became the objects of public attention and admiration, along with daily media praise.

And Oppenheimer, the chief director of the Manhattan Project, gradually began to send out a warning voice to humanity.

And then, swept up in the McCarthyite frenzy of the Cold War, he falls into disrepute as a sort of role model.

On the surface, it was just a case of one scientist being excommunicated.

But all scientists have come to realize that challenging national policy in the future will have serious consequences.

In the years following World War II, scientists emerged as a new breed of intellectuals.

They could contribute their expertise to policymaking not only as scientists but also as public philosophers.

With Oppenheimer out of the picture, scientists realized that they would henceforth be able to serve the nation only as experts on narrow scientific issues.

As sociologist Daniel Bell later noted, Oppenheimer's ordeal was symbolic of the end of "scientists' role as saviors" in the postwar period. —From the text

This book is largely divided into five parts.

Part 1 shows Oppenheimer's family history, childhood, and his development as a physicist, while Part 2 examines Oppenheimer's long-term lover and wife, as well as the encounters that changed his life.

Part 3 depicts Oppenheimer's activities as the general director of the Manhattan Project and the moment of success of the Trinity atomic bomb test, while Part 4 focuses on his changed state of mind and position following the dropping of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima.

Part 5 covers Oppenheimer's later years, including his humiliation and resignation from the security hearings that were intertwined with McCarthyism.

Being a scientist is like climbing a mountain through a tunnel.

It is unclear whether the other side of the tunnel continues upwards or if there is an exit. —Oppenheimer

A model boy with a dry temper enters the world.

When Oppenheimer's idealism got him into trouble, I felt it was the logical consequence of the excellent ethics education we had received.

A student of Felix Adler and John Lovejoy Eliot would act according to his conscience, no matter how unwise the choice. —Daisy Newman (classmate at Ethical Culture School)

Robert Oppenheimer's childhood was one of careful care and generous encouragement of his genius.

Oppenheimer, who grew up in a wealthy family with parents who were first- and second-generation German immigrants, attended the New York School of Ethical Culture, a school that, as its founder Adler taught, allowed people to see the world “not as it is, but how it can be changed.”

Oppenheimer, a sensitive and introverted boy genius, gradually encountered a wider world here with his lifelong mentor, teacher Herbert Smith.

It was also the time when he first traveled to New Mexico, a state he had loved all his life.

The Perro Caliente ranch, where the Oppenheimer family often stayed, became his lifelong retreat.

The nearby Los Alamos Ranch School site, first visited in 1922, would later become the birthplace of the Manhattan Project.

The Wandering Youth and the Poisoned Apple Incident

After graduating from the Ethical Culture School with excellent grades, Oppenheimer entered a completely different world: Harvard University.

He displayed a wealth of knowledge in various fields of interest, including reading Spinoza and Freud and writing poetry.

He graduated summa cum laude with a bachelor's degree in chemistry in three years, but was more interested in physics and chose Cambridge, England, "closer to the center" of the physics world, where he studied under Nobel Prize winner in physics (1906), J.

I went into J. Thompson's laboratory.

However, his neuroticism worsened here, particularly his frustration and jealousy at not being accepted by his supervisor, the experimental physicist Professor Blackett, which led to his outburst of placing (or claiming to have placed) a 'poisoned' apple on Blackett's desk, a situation that was resolved on the condition of psychiatric counseling.

The literary works he enjoyed reading, such as Proust, stabilized his mind.

To Göttingen, the scene of the modern physics revolution

As soon as I met Oppenheimer, I knew he was a man of great talent. —Max Born

After a difficult year at Cambridge, Oppenheimer finally found enjoyment in theoretical physics.

Max Born, director of the Institute for Theoretical Physics at the University of Göttingen, was impressed by Oppenheimer's struggle with the theoretical problems raised by Heisenberg and Schrödinger in recent papers.

At Born's invitation, he moved to the University of Göttingen, where he interacted with James Frank, Otto Hahn, George Wellenbeck, Paul Dirac, and Johann von Neumann.

Born, who won the 1954 Nobel Prize in Physics, coined the term "quantum mechanics" in 1924 and proposed that the outcome of interactions in the quantum world would be determined by probability.

Born, a pacifist and a Jew, was an ideal teacher for a sensitive young student like Oppenheimer.

Oppenheimer, a 23-year-old graduate student, published a whopping 17 papers during his stay in Göttingen.

Göttingen was the site of great revolutions in theoretical physics, including Max Planck's discovery of the quantum, Einstein's great achievement of special relativity, Bohr's theoretical explanation of the behavior of the hydrogen atom, Heisenberg's matrix mechanics, and Schrödinger's theory of wave mechanics.

In 1926, Heisenberg and Dirac were 24, Pauli was 26, and Jordan was 23.

Wolfgang Pauli began calling quantum mechanics "boy's physics" (Knabenphysik).

The anxious state of mind of a year ago had been replaced by confidence, and Oppenheimer was a rising star.

Turning the wasteland of physics into a holy land

After successfully receiving his doctorate from Göttingen, Oppenheimer stayed for a while in Leiden and Zurich to conduct research before returning to the United States.

Oppenheimer agreed to teach one semester each at the California Institute of Technology and the University of California, Berkeley.

He chose Berkeley because he thought Berkeley, with its weak theoretical physics field, was a “desert” and “a good place to start something new.”

By focusing on unsolved problems in physics, Oppenheimer gave his students the thrill of being at the forefront of knowledge.

Word began to spread nationwide that if you wanted to major in this field, you had to go to Berkeley.

Oppenheimer loved quantum mechanics for its abstract beauty, but it would soon become a theory that would revolutionize the way humanity relates to the world.

Quantum mechanics describes nature in a way that seems absurd from a common-sense perspective.

But it fits well with the experimental results.

Therefore, I hope you can accept nature as it is.

Nature is inherently irrational. —Richard Feynman

The Rise of the Nazis and the Political Adventures of a Jewish Professor

What on earth has politics to do with truth, goodness, and beauty? —Robert Oppenheimer

A new ordeal came to physicist Oppenheimer, who had been actively engaged in academic activities since the late 1920s.

Oppenheimer, a liberal who pursued aesthetics, also had no choice but to become interested in political issues when Hitler seized power in Germany in 1933.

In April of that year, Jewish German professors were expelled from universities in Germany without any apparent reason.

In the spring of 1934, Oppenheimer saw an advertisement for a fundraising campaign to help German physicists emigrate from Nazi Germany and pledged to send 3 percent of his annual salary (about $100 a year) for the next two years.

“Around 1936 my interests began to change,” Oppenheimer explained to his interrogators in 1954.

I had a persistent and gnawing anger at what the Jews were going through in Germany.

I had relatives in Germany, and I helped them come to the United States.

I saw the impact the Great Depression had on my students.

They were forced to seek inadequate employment, and in many cases, were unable to find employment at all.

Through them, I came to understand how political and economic events can have such a profound impact on human life.

I began to feel the need to participate more actively in the life of the community. —Robert Oppenheimer

Love of a lifetime, but many loves

1936 was also the year Oppenheimer first met Gene Tatlock.

Jean, a psychology student who later became a psychiatrist, was Oppenheimer's "true love."

It was Jin's passionate personality that moved Oppenheimer from theory to action.

Jin's activist nature and social consciousness may have inspired Oppenheimer's sense of social responsibility, which he discussed during his time at the Ethical Culture School.

Although she was known to be a Communist, it was the cause that mattered more than the party, and by the autumn of 1936 the cause that most preoccupied her was the troubled Spanish Republic.

After breaking up with Gene, who had no intention of marrying, Oppenheimer met Catherine 'Kitty' Puning Harrison, who would become his wife.

One of her former husbands, Joe Dallet, was also a republican who fought in the Spanish Civil War.

According to Robert Thurber, Oppenheimer's protégé and friend, "her interest was in advancing Oppenheimer's career."

He and Kitty had two children and cared for each other throughout their lives.

However, his relationship with Jin continued until she committed suicide under mysterious circumstances, which later led to him being accused of being a Soviet spy.

Attempts to label Oppenheimer a communist were futile.

Oppenheimer was surrounded by several relatives, friends, and colleagues who had once been Communists.

The most important fact about Oppenheimer's political career is that he was committed to social and economic justice in America in the 1930s, and that he chose to side with the left to achieve this goal.

Oppenheimer always wanted to be able to think freely and make his own political choices.

The Manhattan Project, an unprecedented plan

Enough has been done about the Spanish problem.

The world faces other, more pressing crises. —Robert Oppenheimer

Oppenheimer's name was being mentioned among government officials as a candidate to lead the top-secret military research laboratory to develop the atomic bomb.

On September 1, 1939, a month before the start of war in Europe, Einstein sent a letter to President Franklin Roosevelt warning that “a new kind of extremely powerful bomb may be built.”

The Uranium Commission, established at this time, received a report two years later on a new weapon that it said would "decide the outcome of the war," and a new commission directly under the White House was formed.

Despite opposition to his past political activities and association with communists, he was selected to lead the Manhattan Project at the age of just 38.

Oppenheimer's contributions to uranium-related meetings were so significant that the work became impossible without him.

He possessed not only great understanding and passion, but also people skills.

Through 15 years of scientific achievements and diverse social life, Oppenheimer transformed from an immature scientific prodigy into a sophisticated and charismatic leader.

The flower of theoretical physics blooming in the desert

Here in Los Alamos, I discovered the spirit of the Athenian, Platonic, ideal republic. —James Turk

A massive research station was to be built in the desert highlands of New Mexico.

Oppenheimer had often fantasized about pursuing both his passions for physics and the New Mexico desert, and the perfect opportunity finally presented itself.

Oppenheimer pointed out that several groups working on fast neutron fission in Princeton, Chicago, and Berkeley were doing the same thing over and over again, and he urged them to come together and work together.

He was put in charge of integrating the research and development activities of Manhattan Project agencies spread across the country to create a usable nuclear weapon.

The secret laboratory built at Los Alamos was a village with 4,000 civilians, including scientists and engineers, and 2,000 military personnel.

Isidore Rabi, who advised the Manhattan Project at Oppenheimer's request, once said he did not want to mark the "culmination of 300 years of physics" by building weapons of mass destruction.

While Rabih was already concerned with the ethical issues of the atomic bomb, Oppenheimer had no time to worry about metaphysical issues.

I too believe that this project stands at the 'culmination of 300 years of physics,' but I disagree with you.

To me, this is the creation of a weapon that is quite important during wartime.

I don't think the Nazis will give us a choice. —Robert Oppenheimer

Towards an open world

It is clear that we have already achieved great scientific and technological achievements that will undoubtedly have a profound impact on the future of humanity.

In the near future, unprecedented weapons will be developed that will completely change the nature of war.

If we fail to reach agreement on how to control this new substance in the near future, the permanent threat to humanity's survival will far outweigh any temporary benefits it may bring. — Niels Bohr

Bohr traveled between Germany and the United States on the Manhattan Project and had a profound influence on Oppenheimer.

For Bohr, a communal culture of scientific inquiry could foster progress and rationality while also fostering peace.

Therefore, after the war, the world's nations had to be confident that no potential adversary was stockpiling nuclear weapons.

That was only possible in an 'open world' where international observers had full information about what was happening in each country's military and industrial facilities and about new scientific discoveries.

Debate over the ethical and political issues surrounding the atomic bomb became a growing concern among scientists at Los Alamos.

The young physicist Louis Rosen remembers Oppenheimer speaking on the topic of "Is it right for this country to use nuclear weapons against living human beings?" and saying, "We are all meant to live in constant fear, but the bomb might also end all wars."

And this hope was persuasive to the scientists gathered at the time.

Scientists knew that this device would change the concept of national sovereignty.

They trusted Franklin Roosevelt and believed he was creating a United Nations to solve this very puzzle.

There will be territories without sovereignty, and sovereignty will reside with the United Nations.

It means an end to war as we know it, and that is the promise.

That's why I was able to continue this project. —Robert Wilson

From Trinity to Hiroshima

The first flash of light rose from the ground and penetrated my eyelids.

When I first looked up, I saw a fireball, and right after that, I saw clouds rising that seemed out of this world.

It was very bright and very purple.

I thought maybe it would flow this way and swallow us up. —Frank Oppenheimer

As World War II drew to a close, scientists at Los Alamos also grew impatient.

On April 30, 1945, Hitler committed suicide, and eight days later, Germany surrendered.

When Segre heard the news, his first words were, “We’re too late.”

The scientists at Los Alamos based the project's legitimacy on the Nazis' submission.

“Now that the bomb could no longer be used against the Nazis, doubts began to arise,” Segre wrote in his memoirs.

Then, finally, on July 14th, the Trinity nuclear test was successfully conducted.

The joy of a successful study, pure dedication to the next one.

For many scientists, including Richard Feynman, it was a moving moment to stand at the historic site.

But after the nuclear tests were over, Oppenheimer was faced with a deeper concern about responsibility, separate from the sense of accomplishment that enveloped Los Alamos.

The atomic bomb, built under Oppenheimer's direction, was about to be used.

But he reminded himself that it would be used in a way that would not trigger an arms race with the Soviet Union.

One man against the super bomb

Now I am death, the destroyer of worlds. - From the Bhagavad Gita

Immediately after the war, Oppenheimer warned that the existence of nuclear weapons would pose a threat to the United States and, by extension, the entire world.

America's nuclear monopoly could not be maintained.

Like other scientists involved in the Manhattan Project, he believed the Soviet Union could break the American nuclear monopoly within three to five years.

The illusion that possessing nuclear weapons would protect America's security was a dangerous one.

Oppenheimer, who had been forced to fight against the Cold War military establishment, abandoned any hope of improvement in the nuclear disarmament situation by 1949 and continued to use his influence to discredit the government and the public's fascination with nuclear energy.

He also discussed the potential risks inherent in civilian nuclear power plants.

Such remarks were enough to draw the ire of those in the Department of Defense and the power industry who favored the development of nuclear-based technologies.

He still believed that Bohr's vision of global openness was the only hope for humanity in the nuclear age.

However, nuclear arms control negotiations held at the United Nations in the early Cold War were deadlocked.

But he did not give up, emphasizing the importance of global openness and information sharing.

“We cannot act properly when information is kept to a very small number of people due to secrecy and fear,” he asserted.

Oppenheimer concluded that the only remedy was “honesty.”

We created a weapon so terrible that it changed the world in an instant.

By creating it, we have asked the question: Is science really only good for humanity? —Robert Oppenheimer

A modern-day Galileo, the master of open minds

When he was suffering because he was at the center of controversy during the dark ages of the 1950s, I asked him if he had ever thought of going abroad to live, saying that foreign universities would welcome him if he wanted to.

He answered.

“Damn it, I love this country.”―George Frost Kennan

Oppenheimer became the most visible victim of McCarthy's anti-communist hysteria at its peak.

He spearheaded efforts to harness the power of the atom, but when he tried to warn his countrymen of the dangers—that is, when he argued that the United States should reduce its reliance on nuclear weapons—the U.S. government questioned his loyalty and brought him to trial.

As in Freeman Dyson's "Faust's Bargain," Oppenheimer tried to renegotiate the terms of the deal, but was cut out for it.

Historian Barton Bernstein wrote, “This was ultimately a triumph of McCarthyism without McCarthy.”

After the 1954 security hearings, Oppenheimer as a public figure ceased to exist… … .

He was one of the most famous people in the world.

Countless people admired him, quoted him, took pictures of him, sought his advice, and showered him with praise.

He was deified as the archetype of a new kind of hero, a hero of science and intellect, the initiator and living symbol of a new atomic age.

And suddenly, all the glory was gone, and he was gone too. —Robert Coughlan

The security hearing, which was led by Lewis Strauss, chairman of the board of trustees at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, and which included malicious accusations, illegal wiretaps, and even the humiliation of his personal love life, has ended.

Strauss delayed the vote to retain Oppenheimer as director for several months to avoid appearing to be acting out of personal vendetta.

Meanwhile, the Institute for Advanced Study professors had time to write an open letter in support of Oppenheimer and collect signatures, and all tenured professors at the Institute signed it.

Oppenheimer was able to maintain his position at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton until his death in 1967 from throat cancer, a condition he acquired from his smoking habit that became his trademark, along with his fedora.

The Cold War ended worldwide.

But a nuclear confrontation on the Korean Peninsula remains a terrifying reality.

Oppenheimer understood clearly from the beginning that nuclear proliferation was inevitable.

Oppenheimer's plan for international nuclear weapons control, proposed in 1946, remains valid today.

Oppenheimer's life and struggles will be of practical value to Korean readers more than anyone else. ―Kai Bird and Martin Sherwin, Preface to the Korean Edition

The Life of Robert Oppenheimer, Father of the Atomic Bomb

Rereading Oppenheimer in the Age of Nuclear Crisis

If a nation isolated from the mainstream of international science, culture, and commerce, and even failing to feed its own people, can produce nuclear weapons, it clearly shows that the global proliferation of nuclear weapons is not so difficult. —Kai Bird and Martin Sherwin, Preface to the Korean Edition

A statement released at the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) Ministerial Meeting held in Hanoi, Vietnam on July 24th called for the resumption of the six-party talks on North Korea's nuclear program.

Despite its commitment to denuclearization at the 2005 Six-Party Talks, North Korea conducted nuclear tests using enriched plutonium in 2006 and 2009, and announced in May that it had successfully achieved a nuclear fusion reaction.

And, by refusing to give up its nuclear facilities to counter financial sanctions against various provocations, it is heightening tensions in the international community.

This situation was predicted as early as the last century, when nuclear weapons were first created.

And in our country, where this sharp conflict is currently ongoing, the person who deserves attention is Robert Oppenheimer.

Nuclear weapons, born in the race to win World War II, have literally become 'bombs' due to their enormous destructive power and potential for abuse immediately after their birth.

It also brought about dramatic moments in the life of Oppenheimer, the director of the Manhattan Project that developed the atomic bomb and the 'father of the atomic bomb'.

This time, 『American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J.

Robert Oppenheimer) is the definitive biography of Oppenheimer, written by two authors, journalist Kai Bird and Martin Sherwin, professor of English literature and American history, after 25 years of research, interviews, and reading FBI documents.

Upon its publication in 2005, American Prometheus won the National Book Critics Circle (NBCC) Award for Biography and the Pulitzer Prize for Biography or Autobiography in 2006.

Knowledge itself is the foundation of civilization.

But broadening the scope of knowledge places greater responsibility on individuals and nations through the possibility of shaping the conditions of human life. — Niels Bohr

The Life of Oppenheimer, America's Prometheus

Prometheus, a character in Greek mythology, stole fire from Zeus and gave it to humans, and was punished by having an eagle peck out his liver every day.

As Scientific Monthly wrote after the Hiroshima atomic bombing, “The modern Prometheus has once again stormed Mount Olympus, bringing back Zeus’ thunderbolts for humanity,” the scientists who participated in the Manhattan Project became the objects of public attention and admiration, along with daily media praise.

And Oppenheimer, the chief director of the Manhattan Project, gradually began to send out a warning voice to humanity.

And then, swept up in the McCarthyite frenzy of the Cold War, he falls into disrepute as a sort of role model.

On the surface, it was just a case of one scientist being excommunicated.

But all scientists have come to realize that challenging national policy in the future will have serious consequences.

In the years following World War II, scientists emerged as a new breed of intellectuals.

They could contribute their expertise to policymaking not only as scientists but also as public philosophers.

With Oppenheimer out of the picture, scientists realized that they would henceforth be able to serve the nation only as experts on narrow scientific issues.

As sociologist Daniel Bell later noted, Oppenheimer's ordeal was symbolic of the end of "scientists' role as saviors" in the postwar period. —From the text

This book is largely divided into five parts.

Part 1 shows Oppenheimer's family history, childhood, and his development as a physicist, while Part 2 examines Oppenheimer's long-term lover and wife, as well as the encounters that changed his life.

Part 3 depicts Oppenheimer's activities as the general director of the Manhattan Project and the moment of success of the Trinity atomic bomb test, while Part 4 focuses on his changed state of mind and position following the dropping of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima.

Part 5 covers Oppenheimer's later years, including his humiliation and resignation from the security hearings that were intertwined with McCarthyism.

Being a scientist is like climbing a mountain through a tunnel.

It is unclear whether the other side of the tunnel continues upwards or if there is an exit. —Oppenheimer

A model boy with a dry temper enters the world.

When Oppenheimer's idealism got him into trouble, I felt it was the logical consequence of the excellent ethics education we had received.

A student of Felix Adler and John Lovejoy Eliot would act according to his conscience, no matter how unwise the choice. —Daisy Newman (classmate at Ethical Culture School)

Robert Oppenheimer's childhood was one of careful care and generous encouragement of his genius.

Oppenheimer, who grew up in a wealthy family with parents who were first- and second-generation German immigrants, attended the New York School of Ethical Culture, a school that, as its founder Adler taught, allowed people to see the world “not as it is, but how it can be changed.”

Oppenheimer, a sensitive and introverted boy genius, gradually encountered a wider world here with his lifelong mentor, teacher Herbert Smith.

It was also the time when he first traveled to New Mexico, a state he had loved all his life.

The Perro Caliente ranch, where the Oppenheimer family often stayed, became his lifelong retreat.

The nearby Los Alamos Ranch School site, first visited in 1922, would later become the birthplace of the Manhattan Project.

The Wandering Youth and the Poisoned Apple Incident

After graduating from the Ethical Culture School with excellent grades, Oppenheimer entered a completely different world: Harvard University.

He displayed a wealth of knowledge in various fields of interest, including reading Spinoza and Freud and writing poetry.

He graduated summa cum laude with a bachelor's degree in chemistry in three years, but was more interested in physics and chose Cambridge, England, "closer to the center" of the physics world, where he studied under Nobel Prize winner in physics (1906), J.

I went into J. Thompson's laboratory.

However, his neuroticism worsened here, particularly his frustration and jealousy at not being accepted by his supervisor, the experimental physicist Professor Blackett, which led to his outburst of placing (or claiming to have placed) a 'poisoned' apple on Blackett's desk, a situation that was resolved on the condition of psychiatric counseling.

The literary works he enjoyed reading, such as Proust, stabilized his mind.

To Göttingen, the scene of the modern physics revolution

As soon as I met Oppenheimer, I knew he was a man of great talent. —Max Born

After a difficult year at Cambridge, Oppenheimer finally found enjoyment in theoretical physics.

Max Born, director of the Institute for Theoretical Physics at the University of Göttingen, was impressed by Oppenheimer's struggle with the theoretical problems raised by Heisenberg and Schrödinger in recent papers.

At Born's invitation, he moved to the University of Göttingen, where he interacted with James Frank, Otto Hahn, George Wellenbeck, Paul Dirac, and Johann von Neumann.

Born, who won the 1954 Nobel Prize in Physics, coined the term "quantum mechanics" in 1924 and proposed that the outcome of interactions in the quantum world would be determined by probability.

Born, a pacifist and a Jew, was an ideal teacher for a sensitive young student like Oppenheimer.

Oppenheimer, a 23-year-old graduate student, published a whopping 17 papers during his stay in Göttingen.

Göttingen was the site of great revolutions in theoretical physics, including Max Planck's discovery of the quantum, Einstein's great achievement of special relativity, Bohr's theoretical explanation of the behavior of the hydrogen atom, Heisenberg's matrix mechanics, and Schrödinger's theory of wave mechanics.

In 1926, Heisenberg and Dirac were 24, Pauli was 26, and Jordan was 23.

Wolfgang Pauli began calling quantum mechanics "boy's physics" (Knabenphysik).

The anxious state of mind of a year ago had been replaced by confidence, and Oppenheimer was a rising star.

Turning the wasteland of physics into a holy land

After successfully receiving his doctorate from Göttingen, Oppenheimer stayed for a while in Leiden and Zurich to conduct research before returning to the United States.

Oppenheimer agreed to teach one semester each at the California Institute of Technology and the University of California, Berkeley.

He chose Berkeley because he thought Berkeley, with its weak theoretical physics field, was a “desert” and “a good place to start something new.”

By focusing on unsolved problems in physics, Oppenheimer gave his students the thrill of being at the forefront of knowledge.

Word began to spread nationwide that if you wanted to major in this field, you had to go to Berkeley.

Oppenheimer loved quantum mechanics for its abstract beauty, but it would soon become a theory that would revolutionize the way humanity relates to the world.

Quantum mechanics describes nature in a way that seems absurd from a common-sense perspective.

But it fits well with the experimental results.

Therefore, I hope you can accept nature as it is.

Nature is inherently irrational. —Richard Feynman

The Rise of the Nazis and the Political Adventures of a Jewish Professor

What on earth has politics to do with truth, goodness, and beauty? —Robert Oppenheimer

A new ordeal came to physicist Oppenheimer, who had been actively engaged in academic activities since the late 1920s.

Oppenheimer, a liberal who pursued aesthetics, also had no choice but to become interested in political issues when Hitler seized power in Germany in 1933.

In April of that year, Jewish German professors were expelled from universities in Germany without any apparent reason.

In the spring of 1934, Oppenheimer saw an advertisement for a fundraising campaign to help German physicists emigrate from Nazi Germany and pledged to send 3 percent of his annual salary (about $100 a year) for the next two years.

“Around 1936 my interests began to change,” Oppenheimer explained to his interrogators in 1954.

I had a persistent and gnawing anger at what the Jews were going through in Germany.

I had relatives in Germany, and I helped them come to the United States.

I saw the impact the Great Depression had on my students.

They were forced to seek inadequate employment, and in many cases, were unable to find employment at all.

Through them, I came to understand how political and economic events can have such a profound impact on human life.

I began to feel the need to participate more actively in the life of the community. —Robert Oppenheimer

Love of a lifetime, but many loves

1936 was also the year Oppenheimer first met Gene Tatlock.

Jean, a psychology student who later became a psychiatrist, was Oppenheimer's "true love."

It was Jin's passionate personality that moved Oppenheimer from theory to action.

Jin's activist nature and social consciousness may have inspired Oppenheimer's sense of social responsibility, which he discussed during his time at the Ethical Culture School.

Although she was known to be a Communist, it was the cause that mattered more than the party, and by the autumn of 1936 the cause that most preoccupied her was the troubled Spanish Republic.

After breaking up with Gene, who had no intention of marrying, Oppenheimer met Catherine 'Kitty' Puning Harrison, who would become his wife.

One of her former husbands, Joe Dallet, was also a republican who fought in the Spanish Civil War.

According to Robert Thurber, Oppenheimer's protégé and friend, "her interest was in advancing Oppenheimer's career."

He and Kitty had two children and cared for each other throughout their lives.

However, his relationship with Jin continued until she committed suicide under mysterious circumstances, which later led to him being accused of being a Soviet spy.

Attempts to label Oppenheimer a communist were futile.

Oppenheimer was surrounded by several relatives, friends, and colleagues who had once been Communists.

The most important fact about Oppenheimer's political career is that he was committed to social and economic justice in America in the 1930s, and that he chose to side with the left to achieve this goal.

Oppenheimer always wanted to be able to think freely and make his own political choices.

The Manhattan Project, an unprecedented plan

Enough has been done about the Spanish problem.

The world faces other, more pressing crises. —Robert Oppenheimer

Oppenheimer's name was being mentioned among government officials as a candidate to lead the top-secret military research laboratory to develop the atomic bomb.

On September 1, 1939, a month before the start of war in Europe, Einstein sent a letter to President Franklin Roosevelt warning that “a new kind of extremely powerful bomb may be built.”

The Uranium Commission, established at this time, received a report two years later on a new weapon that it said would "decide the outcome of the war," and a new commission directly under the White House was formed.

Despite opposition to his past political activities and association with communists, he was selected to lead the Manhattan Project at the age of just 38.

Oppenheimer's contributions to uranium-related meetings were so significant that the work became impossible without him.

He possessed not only great understanding and passion, but also people skills.

Through 15 years of scientific achievements and diverse social life, Oppenheimer transformed from an immature scientific prodigy into a sophisticated and charismatic leader.

The flower of theoretical physics blooming in the desert

Here in Los Alamos, I discovered the spirit of the Athenian, Platonic, ideal republic. —James Turk

A massive research station was to be built in the desert highlands of New Mexico.

Oppenheimer had often fantasized about pursuing both his passions for physics and the New Mexico desert, and the perfect opportunity finally presented itself.

Oppenheimer pointed out that several groups working on fast neutron fission in Princeton, Chicago, and Berkeley were doing the same thing over and over again, and he urged them to come together and work together.

He was put in charge of integrating the research and development activities of Manhattan Project agencies spread across the country to create a usable nuclear weapon.

The secret laboratory built at Los Alamos was a village with 4,000 civilians, including scientists and engineers, and 2,000 military personnel.

Isidore Rabi, who advised the Manhattan Project at Oppenheimer's request, once said he did not want to mark the "culmination of 300 years of physics" by building weapons of mass destruction.

While Rabih was already concerned with the ethical issues of the atomic bomb, Oppenheimer had no time to worry about metaphysical issues.

I too believe that this project stands at the 'culmination of 300 years of physics,' but I disagree with you.

To me, this is the creation of a weapon that is quite important during wartime.

I don't think the Nazis will give us a choice. —Robert Oppenheimer

Towards an open world

It is clear that we have already achieved great scientific and technological achievements that will undoubtedly have a profound impact on the future of humanity.

In the near future, unprecedented weapons will be developed that will completely change the nature of war.

If we fail to reach agreement on how to control this new substance in the near future, the permanent threat to humanity's survival will far outweigh any temporary benefits it may bring. — Niels Bohr

Bohr traveled between Germany and the United States on the Manhattan Project and had a profound influence on Oppenheimer.

For Bohr, a communal culture of scientific inquiry could foster progress and rationality while also fostering peace.

Therefore, after the war, the world's nations had to be confident that no potential adversary was stockpiling nuclear weapons.

That was only possible in an 'open world' where international observers had full information about what was happening in each country's military and industrial facilities and about new scientific discoveries.

Debate over the ethical and political issues surrounding the atomic bomb became a growing concern among scientists at Los Alamos.

The young physicist Louis Rosen remembers Oppenheimer speaking on the topic of "Is it right for this country to use nuclear weapons against living human beings?" and saying, "We are all meant to live in constant fear, but the bomb might also end all wars."

And this hope was persuasive to the scientists gathered at the time.

Scientists knew that this device would change the concept of national sovereignty.

They trusted Franklin Roosevelt and believed he was creating a United Nations to solve this very puzzle.

There will be territories without sovereignty, and sovereignty will reside with the United Nations.

It means an end to war as we know it, and that is the promise.

That's why I was able to continue this project. —Robert Wilson

From Trinity to Hiroshima

The first flash of light rose from the ground and penetrated my eyelids.

When I first looked up, I saw a fireball, and right after that, I saw clouds rising that seemed out of this world.

It was very bright and very purple.

I thought maybe it would flow this way and swallow us up. —Frank Oppenheimer

As World War II drew to a close, scientists at Los Alamos also grew impatient.

On April 30, 1945, Hitler committed suicide, and eight days later, Germany surrendered.

When Segre heard the news, his first words were, “We’re too late.”

The scientists at Los Alamos based the project's legitimacy on the Nazis' submission.

“Now that the bomb could no longer be used against the Nazis, doubts began to arise,” Segre wrote in his memoirs.

Then, finally, on July 14th, the Trinity nuclear test was successfully conducted.

The joy of a successful study, pure dedication to the next one.

For many scientists, including Richard Feynman, it was a moving moment to stand at the historic site.

But after the nuclear tests were over, Oppenheimer was faced with a deeper concern about responsibility, separate from the sense of accomplishment that enveloped Los Alamos.

The atomic bomb, built under Oppenheimer's direction, was about to be used.

But he reminded himself that it would be used in a way that would not trigger an arms race with the Soviet Union.

One man against the super bomb

Now I am death, the destroyer of worlds. - From the Bhagavad Gita

Immediately after the war, Oppenheimer warned that the existence of nuclear weapons would pose a threat to the United States and, by extension, the entire world.

America's nuclear monopoly could not be maintained.

Like other scientists involved in the Manhattan Project, he believed the Soviet Union could break the American nuclear monopoly within three to five years.

The illusion that possessing nuclear weapons would protect America's security was a dangerous one.

Oppenheimer, who had been forced to fight against the Cold War military establishment, abandoned any hope of improvement in the nuclear disarmament situation by 1949 and continued to use his influence to discredit the government and the public's fascination with nuclear energy.

He also discussed the potential risks inherent in civilian nuclear power plants.

Such remarks were enough to draw the ire of those in the Department of Defense and the power industry who favored the development of nuclear-based technologies.

He still believed that Bohr's vision of global openness was the only hope for humanity in the nuclear age.

However, nuclear arms control negotiations held at the United Nations in the early Cold War were deadlocked.

But he did not give up, emphasizing the importance of global openness and information sharing.

“We cannot act properly when information is kept to a very small number of people due to secrecy and fear,” he asserted.

Oppenheimer concluded that the only remedy was “honesty.”

We created a weapon so terrible that it changed the world in an instant.

By creating it, we have asked the question: Is science really only good for humanity? —Robert Oppenheimer

A modern-day Galileo, the master of open minds

When he was suffering because he was at the center of controversy during the dark ages of the 1950s, I asked him if he had ever thought of going abroad to live, saying that foreign universities would welcome him if he wanted to.

He answered.

“Damn it, I love this country.”―George Frost Kennan

Oppenheimer became the most visible victim of McCarthy's anti-communist hysteria at its peak.

He spearheaded efforts to harness the power of the atom, but when he tried to warn his countrymen of the dangers—that is, when he argued that the United States should reduce its reliance on nuclear weapons—the U.S. government questioned his loyalty and brought him to trial.

As in Freeman Dyson's "Faust's Bargain," Oppenheimer tried to renegotiate the terms of the deal, but was cut out for it.

Historian Barton Bernstein wrote, “This was ultimately a triumph of McCarthyism without McCarthy.”

After the 1954 security hearings, Oppenheimer as a public figure ceased to exist… … .

He was one of the most famous people in the world.

Countless people admired him, quoted him, took pictures of him, sought his advice, and showered him with praise.

He was deified as the archetype of a new kind of hero, a hero of science and intellect, the initiator and living symbol of a new atomic age.

And suddenly, all the glory was gone, and he was gone too. —Robert Coughlan

The security hearing, which was led by Lewis Strauss, chairman of the board of trustees at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, and which included malicious accusations, illegal wiretaps, and even the humiliation of his personal love life, has ended.

Strauss delayed the vote to retain Oppenheimer as director for several months to avoid appearing to be acting out of personal vendetta.

Meanwhile, the Institute for Advanced Study professors had time to write an open letter in support of Oppenheimer and collect signatures, and all tenured professors at the Institute signed it.

Oppenheimer was able to maintain his position at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton until his death in 1967 from throat cancer, a condition he acquired from his smoking habit that became his trademark, along with his fedora.

The Cold War ended worldwide.

But a nuclear confrontation on the Korean Peninsula remains a terrifying reality.

Oppenheimer understood clearly from the beginning that nuclear proliferation was inevitable.

Oppenheimer's plan for international nuclear weapons control, proposed in 1946, remains valid today.

Oppenheimer's life and struggles will be of practical value to Korean readers more than anyone else. ―Kai Bird and Martin Sherwin, Preface to the Korean Edition

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: July 30, 2010

- Format: Hardcover book binding method guide

- Page count, weight, size: 1,152 pages | 1,596g | 145*215*60mm

- ISBN13: 9788983711137

- ISBN10: 8983711132

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)