Korean Plant Ecology Encyclopedia 2

|

Description

Book Introduction

A treasure trove of biodiversity, a home to wild vegetable culture

Recording the value of 'grass'

This is the second book in the 『Encyclopedia of Korean Plant Ecology』 series, which examines the life and society of plants by habitat.

Volume 2 deals with the grassland, a plant community formed under the blazing sun.

Unlike plants that live in shady forests, plants that live in grasslands have formed unique societies that can withstand the scorching sun.

The plant diversity per unit area of grassland is richer than that of forests.

This is why many regions and countries are focusing on grasslands as biodiversity hotspots.

There is one more special reason why we should care about grass.

This is because the 'wild vegetable culture', which cannot be found in any other country in the world, originated from grasslands.

The uniqueness of 'namul', whose meaning cannot be fully expressed in any other language, can be seen in the grass.

We selected 208 species of plants living in grasslands and introduced a total of 501 species by covering related plants together.

The description of each species is meticulously recorded in four major categories: morphological classification, ecological classification, name dictionary, and eco-note. The history and cultural history of grass plants are also richly explained.

Recording the value of 'grass'

This is the second book in the 『Encyclopedia of Korean Plant Ecology』 series, which examines the life and society of plants by habitat.

Volume 2 deals with the grassland, a plant community formed under the blazing sun.

Unlike plants that live in shady forests, plants that live in grasslands have formed unique societies that can withstand the scorching sun.

The plant diversity per unit area of grassland is richer than that of forests.

This is why many regions and countries are focusing on grasslands as biodiversity hotspots.

There is one more special reason why we should care about grass.

This is because the 'wild vegetable culture', which cannot be found in any other country in the world, originated from grasslands.

The uniqueness of 'namul', whose meaning cannot be fully expressed in any other language, can be seen in the grass.

We selected 208 species of plants living in grasslands and introduced a total of 501 species by covering related plants together.

The description of each species is meticulously recorded in four major categories: morphological classification, ecological classification, name dictionary, and eco-note. The history and cultural history of grass plants are also richly explained.

index

Note 4

Author's Preface 8

Why Grass? 10

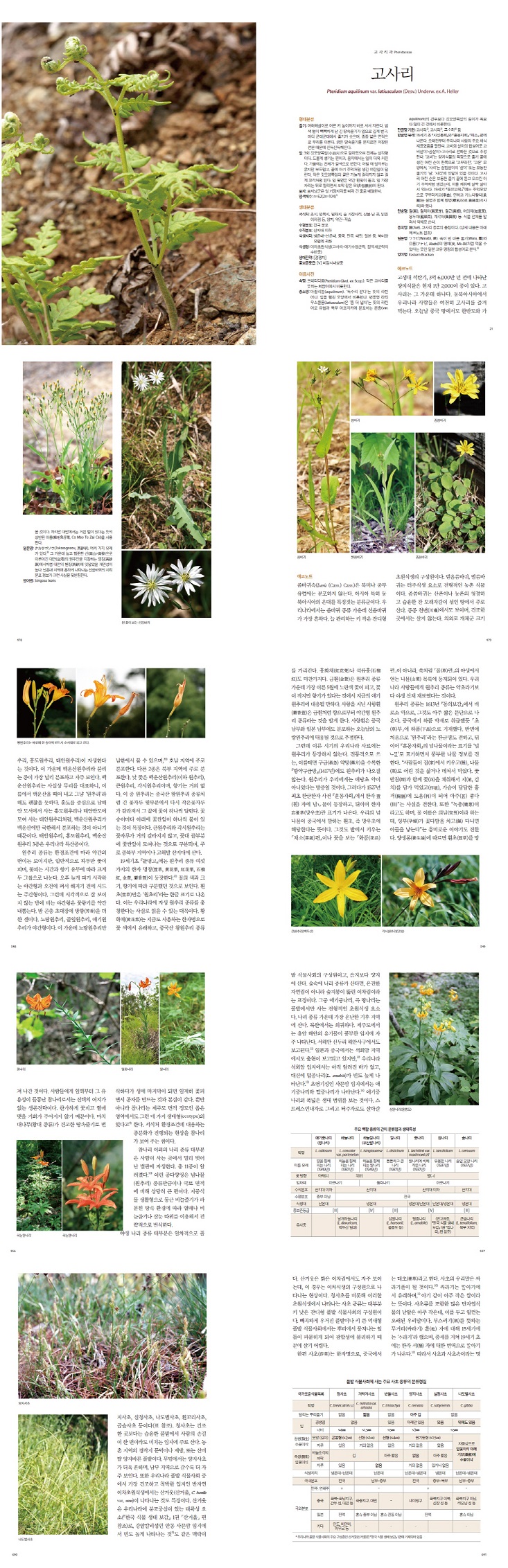

Bracken family 21

Sandalwood and 24

26 of the knotweed family

Caryophyllaceae 48

Ranunculaceae 61

Single-parent family 80

Water parsley and 84

Brassicaceae 88

Panthera tigris alba 97

Rosaceae 100

Beans and 128

Rat's Hand Plant 184

Flax family 193

The polar and 196

Yunhyang and 203

Wonjigwa 208

Asteraceae 216

Violet and 219

Needleflower and 232

Ant Tower and 235

Mountain type 237

Primulaceae 259

Magic and 274

Yongdam and 276

Asteraceae 288

Family Apiaceae 292

Kokduseon Family 298

Dental Clinic 309

Lamiaceae 315

Scrophularia chinensis and 347

371 with heat

Matariidae 379

387 of the mountain rabbit flower

394 bellflowers

Asteraceae 418

Lily and 536

Iris 581

592 of the family Reed and Reed

Gramineae 596

Cyperaceae 684

Orchidaceae 694

supplement

Morphological terminology board 710

Morphological Dictionary 721

Ecological Dictionary 730

References 755

Plant Species Index

Scientific name 781│Korean name 790│English name 807│Chinese name 810│

Japanese name 813

Epilogue 816

Author's Preface 8

Why Grass? 10

Bracken family 21

Sandalwood and 24

26 of the knotweed family

Caryophyllaceae 48

Ranunculaceae 61

Single-parent family 80

Water parsley and 84

Brassicaceae 88

Panthera tigris alba 97

Rosaceae 100

Beans and 128

Rat's Hand Plant 184

Flax family 193

The polar and 196

Yunhyang and 203

Wonjigwa 208

Asteraceae 216

Violet and 219

Needleflower and 232

Ant Tower and 235

Mountain type 237

Primulaceae 259

Magic and 274

Yongdam and 276

Asteraceae 288

Family Apiaceae 292

Kokduseon Family 298

Dental Clinic 309

Lamiaceae 315

Scrophularia chinensis and 347

371 with heat

Matariidae 379

387 of the mountain rabbit flower

394 bellflowers

Asteraceae 418

Lily and 536

Iris 581

592 of the family Reed and Reed

Gramineae 596

Cyperaceae 684

Orchidaceae 694

supplement

Morphological terminology board 710

Morphological Dictionary 721

Ecological Dictionary 730

References 755

Plant Species Index

Scientific name 781│Korean name 790│English name 807│Chinese name 810│

Japanese name 813

Epilogue 816

Detailed image

Into the book

It is a ‘habitat of life’ that is completely different from grasslands and forests.

The forest is dark, the grass is always bright.

If darkness is the regulator of life for forest plants, then in the grassland, intense direct sunlight fundamentally controls life.

--- p.10

Although we habitually use the term 'tiger', it is damaging the dignity and roots of the Korean word 'beom'.

The first word 'tiger' appears in the 1459 『Wolinseokbo』 along with the word 'lion'. Here, the two characters 'ho' (虎) and 'rang' (狼) refer to 'beom' (虎) and 'wili' (狼), respectively, and not to a single species of tiger as is the case today.

At the end of the Joseon Dynasty in the 19th century, when the country was on the verge of collapse, a Westerner published 『Jinri Pyeondok Samjagyeong』, where a tiger turned into a tigress.

--- p.31

When rabbit grass is eaten, it releases cyanide (HCN) from the wounds it leaves behind.

Those with a distinct 'V' shaped white pattern on the leaf surface do so.

Even a small amount of cyanide can cause confusion in light-weight snails and grasshoppers.

The fact that groups of clover with 'V'-shaped patterns are more abundant and common in the wild is a natural result of leaf-eating groups avoiding them.

--- p.167

We become barbarians by committing barbarian acts, not by being called barbarian by others.

This is why I cannot abandon the delicious name ‘Barbarian Flower’ rather than the name ‘Violet Flower’ which I do not understand.

--- p.276

Typically, the parasitic process, in which the seeds of a parasitic plant awaken from dormancy, germinate, and continue to produce parasitic roots, begins only when the host plant releases a chemical signal that will accept the parasite.

For example, the parasite's choice is not its own, but entirely dependent on the host's choice.

So, I don't think it's right to blame parasites as being all bad.

They just live together with the consideration and generosity of the host.

It is a misunderstanding to think that Yago lives by stealing other people's hard work.

There is no shamelessness or timidity in the natural ecosystem.

All are absolutely interdependent.

--- p.378

Doraji is a pure Korean word.

The first written characters are 刀?次 and 都羅次 (doracha), which are borrowed from the Chinese characters that represent the sound of doraji.

In the early 15th century, 『Hyangyak Gugeupbang』 conveyed the Chinese character Gilgyeong (吉梗) in a vulgar rhyme.

In Korean, the first recorded use of 'Dorat' was in the late 15th century in the 『Gugeungganibang』.

After that, Do-eul-ajil, Do-al-at, and Do-eul-la-jil are recorded.

Therefore, it does not originate from the Idu style name Doracha (道羅次).

Doracha (道羅次) is the Idu transcription of the pure Korean word doraji, which our ancestors called since the time when the Korean alphabet did not exist.

--- p.414

The history of using mugwort as a folk medicine is very long.

A boy who was suffering from malaria and was dying was cured by his mother's loving treatment with the scent of mugwort.

This is a story from my childhood in a mountain village in Yeongyang in the mid-1960s.

--- p.426

The original name of the dogwood, 'Taeng-al', comes from the texture and shape of its roots.

In the early 19th century, the notation '알알' appears in the 『Mulmyeonggo』.

It suggests that it may come from a tangled root.

When the rhizome gets old, it becomes hard, and when it dries, it has a slightly odor, but when the root is dug up, it is slightly thick and plump.

The common name 地加乙 (地加乙) and the local name ?加乙 (태가을) recorded in the 1417 Hyangyak Gugeupbang were written using Chinese characters, and were written from the beginning as tangle in tangle.

--- p.443

The reason chives are considered one of the oldest wild vegetables of Koreans is because they are commonly found growing in crevices of limestone rocks on the Korean Peninsula.

Paleolithic people who lived in caves in limestone regions could not help but recognize the peculiar aroma of chives from early on.

Although chives are commonly cultivated today and are known to be native to China, this is a mistake made without any knowledge of the true nature of chives' native habitat.

--- p.541

The long feathers of a pine tree have a four-dimensional structure.

First of all, it looks like a thin but strong wire.

It is more than 10 times longer than the ear of Isaac, and is bent two or three times at large or small angles.

In addition, the lower surface of the cap has a groove that goes to the left like a screw, and there are many strong hairs like thorns.

Finally, it twists to the left like a rope with a neighboring skein, forming a strong wire.

The moment the ear of Isaac lightly touches the soft ground, it turns 'right' and digs into the soil like an excavator.

This is because the long hairs that rise into the air create a large circle due to centrifugal force, creating rotational force.

It digs into the soil with strong rotational force, but the ear of grain is not damaged.

This is because the part of the head of the ear that touches the ground is covered with tough hairs.

It truly seems like a 'godly stroke' to see the dispersal and settlement of the pine tree's seeds.

The forest is dark, the grass is always bright.

If darkness is the regulator of life for forest plants, then in the grassland, intense direct sunlight fundamentally controls life.

--- p.10

Although we habitually use the term 'tiger', it is damaging the dignity and roots of the Korean word 'beom'.

The first word 'tiger' appears in the 1459 『Wolinseokbo』 along with the word 'lion'. Here, the two characters 'ho' (虎) and 'rang' (狼) refer to 'beom' (虎) and 'wili' (狼), respectively, and not to a single species of tiger as is the case today.

At the end of the Joseon Dynasty in the 19th century, when the country was on the verge of collapse, a Westerner published 『Jinri Pyeondok Samjagyeong』, where a tiger turned into a tigress.

--- p.31

When rabbit grass is eaten, it releases cyanide (HCN) from the wounds it leaves behind.

Those with a distinct 'V' shaped white pattern on the leaf surface do so.

Even a small amount of cyanide can cause confusion in light-weight snails and grasshoppers.

The fact that groups of clover with 'V'-shaped patterns are more abundant and common in the wild is a natural result of leaf-eating groups avoiding them.

--- p.167

We become barbarians by committing barbarian acts, not by being called barbarian by others.

This is why I cannot abandon the delicious name ‘Barbarian Flower’ rather than the name ‘Violet Flower’ which I do not understand.

--- p.276

Typically, the parasitic process, in which the seeds of a parasitic plant awaken from dormancy, germinate, and continue to produce parasitic roots, begins only when the host plant releases a chemical signal that will accept the parasite.

For example, the parasite's choice is not its own, but entirely dependent on the host's choice.

So, I don't think it's right to blame parasites as being all bad.

They just live together with the consideration and generosity of the host.

It is a misunderstanding to think that Yago lives by stealing other people's hard work.

There is no shamelessness or timidity in the natural ecosystem.

All are absolutely interdependent.

--- p.378

Doraji is a pure Korean word.

The first written characters are 刀?次 and 都羅次 (doracha), which are borrowed from the Chinese characters that represent the sound of doraji.

In the early 15th century, 『Hyangyak Gugeupbang』 conveyed the Chinese character Gilgyeong (吉梗) in a vulgar rhyme.

In Korean, the first recorded use of 'Dorat' was in the late 15th century in the 『Gugeungganibang』.

After that, Do-eul-ajil, Do-al-at, and Do-eul-la-jil are recorded.

Therefore, it does not originate from the Idu style name Doracha (道羅次).

Doracha (道羅次) is the Idu transcription of the pure Korean word doraji, which our ancestors called since the time when the Korean alphabet did not exist.

--- p.414

The history of using mugwort as a folk medicine is very long.

A boy who was suffering from malaria and was dying was cured by his mother's loving treatment with the scent of mugwort.

This is a story from my childhood in a mountain village in Yeongyang in the mid-1960s.

--- p.426

The original name of the dogwood, 'Taeng-al', comes from the texture and shape of its roots.

In the early 19th century, the notation '알알' appears in the 『Mulmyeonggo』.

It suggests that it may come from a tangled root.

When the rhizome gets old, it becomes hard, and when it dries, it has a slightly odor, but when the root is dug up, it is slightly thick and plump.

The common name 地加乙 (地加乙) and the local name ?加乙 (태가을) recorded in the 1417 Hyangyak Gugeupbang were written using Chinese characters, and were written from the beginning as tangle in tangle.

--- p.443

The reason chives are considered one of the oldest wild vegetables of Koreans is because they are commonly found growing in crevices of limestone rocks on the Korean Peninsula.

Paleolithic people who lived in caves in limestone regions could not help but recognize the peculiar aroma of chives from early on.

Although chives are commonly cultivated today and are known to be native to China, this is a mistake made without any knowledge of the true nature of chives' native habitat.

--- p.541

The long feathers of a pine tree have a four-dimensional structure.

First of all, it looks like a thin but strong wire.

It is more than 10 times longer than the ear of Isaac, and is bent two or three times at large or small angles.

In addition, the lower surface of the cap has a groove that goes to the left like a screw, and there are many strong hairs like thorns.

Finally, it twists to the left like a rope with a neighboring skein, forming a strong wire.

The moment the ear of Isaac lightly touches the soft ground, it turns 'right' and digs into the soil like an excavator.

This is because the long hairs that rise into the air create a large circle due to centrifugal force, creating rotational force.

It digs into the soil with strong rotational force, but the ear of grain is not damaged.

This is because the part of the head of the ear that touches the ground is covered with tough hairs.

It truly seems like a 'godly stroke' to see the dispersal and settlement of the pine tree's seeds.

--- pp.673-674

Publisher's Review

Why We Should Pay Attention to 'Grass'

When we think of plant societies, forests usually come to mind first.

Our country is a country of forests belonging to the temperate forest biome, and any empty land is constantly transformed into forests through the natural power of 'transition', so perhaps this perception is natural.

However, even in temperate regions, there are lands where forests cannot grow (barren lands), and there are also lands that have been formed in a different way from forests, intertwined with human life.

It's a grassy field.

So, grasslands, especially natural grasslands (naturally generated grasslands), are always scattered like small islands in a plant community full of forests.

It is not uncommon to see ice age relics, rare plants, and endemic species in the grasslands, and this is also why biodiversity is so rich.

For this reason, ecologically advanced countries have long paid attention to grassland plant communities.

Some countries have designated the meadows where the Korean iris, a semi-endemic species, lives as natural monuments, and are also making efforts to protect old pastures.

Meanwhile, what is the situation in our country?

Natural grassland vegetation is in danger of extinction.

Of course, there are many reasons, including climate change, but the biggest factors that have contributed to the situation are various developments and a lack of understanding of grasslands.

The misguided and biased love for forests and the short-sighted view of grasslands that has persisted since the Japanese colonial period are also major problems.

For us, the grassland is a place of great cultural and historical significance.

This is because the grassland is where unique 'greens' grow, the meaning of which cannot be clearly explained in any other language such as English, Chinese, or Japanese.

Vegetables are not just food for us.

All the acts of digging, boiling, seasoning, and eating wild vegetables are imbued with our very old traditional culture.

So, if we look into the grass, we can also find our old future.

This is why we need to know and protect the grasslands now.

Understanding the concept of grassland plant communities

There is probably no one who does not know what a meadow is, but if you ask them what the concept of a meadow is, there will be few who can answer clearly.

At the beginning of the book, it explains what grasslands are in terms of plant ecology, how they are classified, and why they are important.

Before getting to know individual species, it will be helpful to get a general idea of the grassland plant community.

Finding More In-Depth Korean Plant Names

We have selected 208 species of plants living in grasslands (501 species in total including related plants) and comprehensively covered their classification, ecology, morphology, geography, culture, and history.

In particular, in Volume 2, the origins and meanings of the scientific names, Korean names, Chinese names, Japanese names, and English names of each species were traced in greater detail and organized separately in a 'Name Dictionary'.

The reason I searched through countless documents to find the origin of Korean words was to find the original names of our plants that were lost or changed during the Japanese colonial period.

As in Volume 1, I provided the names of those who wished to find my name along with a reason.

10 Years, 10 Volumes, a Series Exploring Plant Society

The [Korean Plant Ecology Encyclopedia] series was planned to be published in 10 volumes over 10 years as the work of one author.

Following the first volume, “Plants We Always Encounter Around Us,” published in December 2013, this second volume sheds light on the grassland plant community, and plans are in place to publish the following volumes: “Plants Living by the Sea,” “Plants Living on Rocks and Rocks,” “Plants Living in Wet Land,” “Plants Living in Developed Land,” “Plants Living in Deciduous Broad-Leaf Forests,” “Plants Living in Evergreen Broad-Leaf Forests,” “Plants Living in Subalpine and Alpine Regions,” and “Plants with Unique Distributions.”

When we think of plant societies, forests usually come to mind first.

Our country is a country of forests belonging to the temperate forest biome, and any empty land is constantly transformed into forests through the natural power of 'transition', so perhaps this perception is natural.

However, even in temperate regions, there are lands where forests cannot grow (barren lands), and there are also lands that have been formed in a different way from forests, intertwined with human life.

It's a grassy field.

So, grasslands, especially natural grasslands (naturally generated grasslands), are always scattered like small islands in a plant community full of forests.

It is not uncommon to see ice age relics, rare plants, and endemic species in the grasslands, and this is also why biodiversity is so rich.

For this reason, ecologically advanced countries have long paid attention to grassland plant communities.

Some countries have designated the meadows where the Korean iris, a semi-endemic species, lives as natural monuments, and are also making efforts to protect old pastures.

Meanwhile, what is the situation in our country?

Natural grassland vegetation is in danger of extinction.

Of course, there are many reasons, including climate change, but the biggest factors that have contributed to the situation are various developments and a lack of understanding of grasslands.

The misguided and biased love for forests and the short-sighted view of grasslands that has persisted since the Japanese colonial period are also major problems.

For us, the grassland is a place of great cultural and historical significance.

This is because the grassland is where unique 'greens' grow, the meaning of which cannot be clearly explained in any other language such as English, Chinese, or Japanese.

Vegetables are not just food for us.

All the acts of digging, boiling, seasoning, and eating wild vegetables are imbued with our very old traditional culture.

So, if we look into the grass, we can also find our old future.

This is why we need to know and protect the grasslands now.

Understanding the concept of grassland plant communities

There is probably no one who does not know what a meadow is, but if you ask them what the concept of a meadow is, there will be few who can answer clearly.

At the beginning of the book, it explains what grasslands are in terms of plant ecology, how they are classified, and why they are important.

Before getting to know individual species, it will be helpful to get a general idea of the grassland plant community.

Finding More In-Depth Korean Plant Names

We have selected 208 species of plants living in grasslands (501 species in total including related plants) and comprehensively covered their classification, ecology, morphology, geography, culture, and history.

In particular, in Volume 2, the origins and meanings of the scientific names, Korean names, Chinese names, Japanese names, and English names of each species were traced in greater detail and organized separately in a 'Name Dictionary'.

The reason I searched through countless documents to find the origin of Korean words was to find the original names of our plants that were lost or changed during the Japanese colonial period.

As in Volume 1, I provided the names of those who wished to find my name along with a reason.

10 Years, 10 Volumes, a Series Exploring Plant Society

The [Korean Plant Ecology Encyclopedia] series was planned to be published in 10 volumes over 10 years as the work of one author.

Following the first volume, “Plants We Always Encounter Around Us,” published in December 2013, this second volume sheds light on the grassland plant community, and plans are in place to publish the following volumes: “Plants Living by the Sea,” “Plants Living on Rocks and Rocks,” “Plants Living in Wet Land,” “Plants Living in Developed Land,” “Plants Living in Deciduous Broad-Leaf Forests,” “Plants Living in Evergreen Broad-Leaf Forests,” “Plants Living in Subalpine and Alpine Regions,” and “Plants with Unique Distributions.”

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: September 8, 2016

- Format: Hardcover book binding method guide

- Page count, weight, size: 816 pages | 165*210*40mm

- ISBN13: 9788997429691

- ISBN10: 8997429698

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)