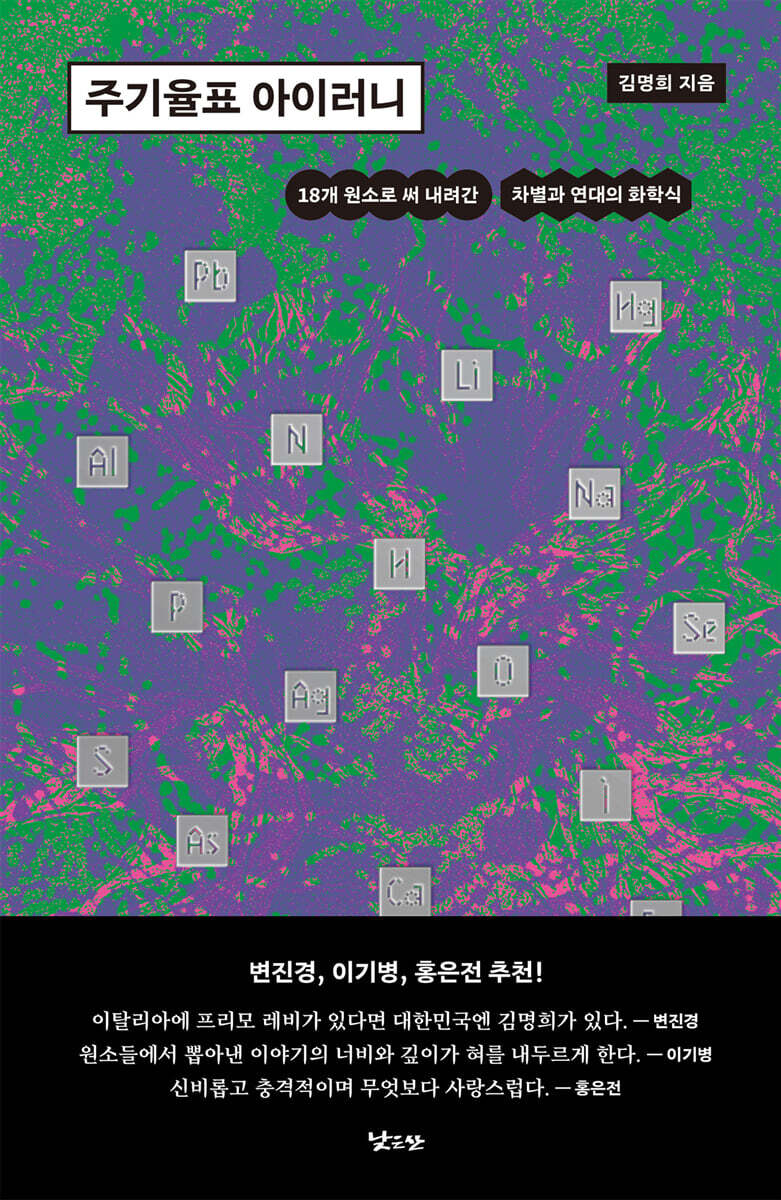

Periodic Table Irony

|

Description

Book Introduction

This project was inspired by the book “The Periodic Table” by Primo Levi, a Holocaust survivor, chemist, and Jewish writer. Korean social scientist Myunghee Kim captured scenes of human society performed on the periodic table with her extensive knowledge and characteristically sharp humor.

By extracting 18 chemical elements that have a close relationship with humans, the author unfolds the turbulent history of these “transcendent” elements, which are neither good nor evil in themselves, across a wide range of time and space to reveal the irony that arises when they combine with humans.

The story unfolds at a rapid pace, crossing the lines of the body and illness, Western society and the Third World, individuals and systems, corporations and governments, science and science fiction, battlefields and space, from each element to the next.

It goes without saying that high-quality data and abundant research cases, placed in the right places, provided a solid fuel for the story to run wild.

In the 'Mercury' section, Primo Levi showed "the madness of a closed community, the pre-modern moral sense, and the eccentricities of people who have difficulty distinguishing between the symptoms of mercury poisoning," while Kim Myung-hee reveals in detail the process by which a 15-year-old boy who was making thermometers in a factory dies from "the fantastic alchemy of corporations and government" that is more lethal than the toxicity of mercury.

When Primo Levi recalls his ancestors, “the respectable Jews of Piedmont,” in the inert nature of “argon,” Kim Myung-hee recalls “today’s atomized modern man.”

If "The Periodic Table" is a memoir by a Holocaust survivor, rich in literary quality, from childhood stories to reflections on humanity, "The Irony of the Periodic Table," which arrived to us exactly 50 years later, can be said to be a periodic table of human society newly mixed on Levy's experimental table.

By extracting 18 chemical elements that have a close relationship with humans, the author unfolds the turbulent history of these “transcendent” elements, which are neither good nor evil in themselves, across a wide range of time and space to reveal the irony that arises when they combine with humans.

The story unfolds at a rapid pace, crossing the lines of the body and illness, Western society and the Third World, individuals and systems, corporations and governments, science and science fiction, battlefields and space, from each element to the next.

It goes without saying that high-quality data and abundant research cases, placed in the right places, provided a solid fuel for the story to run wild.

In the 'Mercury' section, Primo Levi showed "the madness of a closed community, the pre-modern moral sense, and the eccentricities of people who have difficulty distinguishing between the symptoms of mercury poisoning," while Kim Myung-hee reveals in detail the process by which a 15-year-old boy who was making thermometers in a factory dies from "the fantastic alchemy of corporations and government" that is more lethal than the toxicity of mercury.

When Primo Levi recalls his ancestors, “the respectable Jews of Piedmont,” in the inert nature of “argon,” Kim Myung-hee recalls “today’s atomized modern man.”

If "The Periodic Table" is a memoir by a Holocaust survivor, rich in literary quality, from childhood stories to reflections on humanity, "The Irony of the Periodic Table," which arrived to us exactly 50 years later, can be said to be a periodic table of human society newly mixed on Levy's experimental table.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Prologue: The World Seen Through Elements

Iodine_Memories of Scarlet Quarantine

Oxygen_From 'Bulmung' to ECMO, there's oxygen there.

Death of a 15-year-old boy making a mercury thermometer

Hwang_No, I'm going to hell

The irony surrounding sodium salt

Lead_The savior of intelligence who came to destroy intelligence

Argon_Lonely but not lonely

From the 'Mountain of Soaring Silver' to the Birth of Social Medicine

The real culprit who took away carbon vision

Selenium_The Three Laws of Robotics and Humanity

Lithium: The Hidden Birth of an Eco-Friendly Hero

Aluminum_Even the survivors are in pain

The foolish heart that commits hydrogen acid terrorism

Arsenic_Madame Bovary's Resolution

How did the "Morning Star" of the In-Elemental Realm become a lethal weapon?

Iron_The Chronicle of Iron and Blood Between Blood Sucking, Blood Selling, and Blood Donation

Calcium_Life and history engraved in the bones

Human Faces Seen at Nitrogen Extinction Camps

Iodine_Memories of Scarlet Quarantine

Oxygen_From 'Bulmung' to ECMO, there's oxygen there.

Death of a 15-year-old boy making a mercury thermometer

Hwang_No, I'm going to hell

The irony surrounding sodium salt

Lead_The savior of intelligence who came to destroy intelligence

Argon_Lonely but not lonely

From the 'Mountain of Soaring Silver' to the Birth of Social Medicine

The real culprit who took away carbon vision

Selenium_The Three Laws of Robotics and Humanity

Lithium: The Hidden Birth of an Eco-Friendly Hero

Aluminum_Even the survivors are in pain

The foolish heart that commits hydrogen acid terrorism

Arsenic_Madame Bovary's Resolution

How did the "Morning Star" of the In-Elemental Realm become a lethal weapon?

Iron_The Chronicle of Iron and Blood Between Blood Sucking, Blood Selling, and Blood Donation

Calcium_Life and history engraved in the bones

Human Faces Seen at Nitrogen Extinction Camps

Detailed image

Into the book

One day, a person who had been diligently preaching God's word to me on the subway asked me, "Don't you want to go to heaven?" when I refused to listen.

I answered.

“No, I want to go to hell.” He ran to the next compartment.

If it is the infinite power that mankind has dreamed of, the unquenchable fire of hell, there is no reason to refuse it.

Top scientists like Feynman, Hawking, Higgs, Schrödinger, and Einstein are likely already there, having committed the sin of not believing in God, and are likely already developing a technological civilization by utilizing perpetual motion.

Since it has perpetual motion, there is no need to worry about cooling and ventilation.

There's no need to worry about getting bored, because there are many fun writers like Douglas Adams, Kurt Vonnegut, and many other science fiction writers who have already gone before me and established themselves.

Above all, there is no need to frown, as we no longer see anti-gay fan dances, hear bizarre claims that abortion is a sin, evolution is absurd, and homosexuality is a means of socialist revolution.

Wouldn't it be wonderful to be able to burn the sulfurous hellfires with mystical blue flames with your cheerful fellow citizens, in a pleasant environment, without worrying about occupational diseases?

--- From "Hwang: No, I'm going to hell"

Because methanol is observed in large quantities in star-forming regions, it is said to be used as a marker in astronomy to find star-forming regions.

But the traces of methanol we found in a corner of the Earth were not a romantic reminder of the birth of a star, but a warning signal of the extreme combination of labor flexibility and risk outsourcing that makes it impossible to even recognize fellow workers.

On April 17, 2025, while this manuscript was being revised, Lee Jin-hee, one of the victims of methanol poisoning, passed away.

At the young age of 38, he lost his eyesight and suffered from brain damage due to methanol poisoning nine years ago.

The deceased's vivid voice was recorded in the investigation report prepared by the Occupational Health Solidarity at the end of 2016.

“If I were to record my story, who would see it? I don’t think anyone would.

Can I swear? Ha.

I can't help but laugh, seriously, why, why is our country like this, seriously, I have nothing to say, seriously.

I really want to go and find out.

“I have no words, really.” May he rest in peace.

I want to tell him, even though he can't hear.

We are staying and watching your story.

--- From "Carbon: The Real Culprit Who Stolen My Sight"

The stereotypical scenario of 'outsourcing the rise-development-turn-danger' worked without fail this time as well.

This is the shabby side of future industries that utilize cutting-edge technology.

Through subsequent reports, citizens were forced to learn about the properties of lithium, the risks of working with lithium, and even the differences between primary and secondary batteries.

It's like this every time.

In fact, before the Sewol ferry disaster, how many people knew about the existence and meaning of 'ballast water' used on ships?

Disasters keep teaching us unwanted lessons.

--- From "Lithium: The Hidden Birth Story of an Eco-Friendly Hero"

Why on earth am I watching this? Sometimes, I get lost in the TV home shopping screens.

For example, there are moments when sebum is extracted one by one from the bridge of a model's nose, which is enlarged to fill the screen, or when a shopping host passionately shows off her own garak-guksu-like skin after applying soap to her calves.

The unexpected combination of extraordinary product functionality, the wonders of the human body, and professional integrity is simply breathtaking.

Recently, a set of frying pans with a special coating on the triple bottom was added to my admiration list.

Even if you burn the stir-fried octopus seasoned with gochujang, it can be washed cleanly with just a splash of water. Even if you fry scrambled eggs and wheat pancakes right away, they move smoothly like curling stones in the frying pan.

I was absorbed in the screen with my mouth open.

As if the caption "continuous sellout" wasn't an exaggeration, one day on my way to work, I came across the very product that had been delivered to my neighbor's front door.

--- From "Aluminum: Even the Survivors Are in Pain"

The "How dare you!" ideology, or misogyny, which fails to accept women's subjective choices and decisions, is as toxic as acid throughout the world.

To say this would be a great disrespect to hydrogen, which has lit up the night sky with stars and supported life on Earth with its blazing sun for 13.8 billion years.

Do they realize that using such a noble element for such a shameful act of ruining the lives of other human beings is a "cosmic crime of defamation" that tarnishes the reputation of hydrogen, the first element in the universe?

--- From "Hydrogen: The Ugly Heart That Commits Mountain Terrorism"

From the declaration of martial law on December 3, 2024, to the final impeachment of the president on April 4, 2025, for over 100 days, a literal "chaos of chaos" unfolded in our brains.

By repeatedly experiencing events that triggered intense emotional anger, the amygdala, hippocampus, and neurons became more active and connected than ever before, 'imprinting' historical moments on the brain.

However, other precious memories were lost due to severe sleep deprivation and anxiety.

I was able to remember the faces of the military generals, such as the counterintelligence officers and the water defense officers, whom I had never needed to know in my life, but I completely forgot about the live broadcast schedule for the Nobel Prize in Literature award ceremony for author Han Kang, which I had been waiting for.

More vivid than the memories of the trip to Jeju Island with my mother after 20 years, the news footage of the failed attempt to arrest the president that I saw in the living room of my hotel there was vivid.

--- From "Calcium: Life and History Engraved in the Bones"

Not everyone can become a fighter in the face of massive violence and injustice.

But at least I can reflect on what my actions or inactions mean.

History tells us what can happen when we give up even this.

The Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum sells magnets with messages from Holocaust survivors.

The words of a survivor named Roman Kent come to mind.

It is one more commandment added to the Ten Commandments of the Bible.

“Eleventh Commandment: You should never ever be a bystander.”

I answered.

“No, I want to go to hell.” He ran to the next compartment.

If it is the infinite power that mankind has dreamed of, the unquenchable fire of hell, there is no reason to refuse it.

Top scientists like Feynman, Hawking, Higgs, Schrödinger, and Einstein are likely already there, having committed the sin of not believing in God, and are likely already developing a technological civilization by utilizing perpetual motion.

Since it has perpetual motion, there is no need to worry about cooling and ventilation.

There's no need to worry about getting bored, because there are many fun writers like Douglas Adams, Kurt Vonnegut, and many other science fiction writers who have already gone before me and established themselves.

Above all, there is no need to frown, as we no longer see anti-gay fan dances, hear bizarre claims that abortion is a sin, evolution is absurd, and homosexuality is a means of socialist revolution.

Wouldn't it be wonderful to be able to burn the sulfurous hellfires with mystical blue flames with your cheerful fellow citizens, in a pleasant environment, without worrying about occupational diseases?

--- From "Hwang: No, I'm going to hell"

Because methanol is observed in large quantities in star-forming regions, it is said to be used as a marker in astronomy to find star-forming regions.

But the traces of methanol we found in a corner of the Earth were not a romantic reminder of the birth of a star, but a warning signal of the extreme combination of labor flexibility and risk outsourcing that makes it impossible to even recognize fellow workers.

On April 17, 2025, while this manuscript was being revised, Lee Jin-hee, one of the victims of methanol poisoning, passed away.

At the young age of 38, he lost his eyesight and suffered from brain damage due to methanol poisoning nine years ago.

The deceased's vivid voice was recorded in the investigation report prepared by the Occupational Health Solidarity at the end of 2016.

“If I were to record my story, who would see it? I don’t think anyone would.

Can I swear? Ha.

I can't help but laugh, seriously, why, why is our country like this, seriously, I have nothing to say, seriously.

I really want to go and find out.

“I have no words, really.” May he rest in peace.

I want to tell him, even though he can't hear.

We are staying and watching your story.

--- From "Carbon: The Real Culprit Who Stolen My Sight"

The stereotypical scenario of 'outsourcing the rise-development-turn-danger' worked without fail this time as well.

This is the shabby side of future industries that utilize cutting-edge technology.

Through subsequent reports, citizens were forced to learn about the properties of lithium, the risks of working with lithium, and even the differences between primary and secondary batteries.

It's like this every time.

In fact, before the Sewol ferry disaster, how many people knew about the existence and meaning of 'ballast water' used on ships?

Disasters keep teaching us unwanted lessons.

--- From "Lithium: The Hidden Birth Story of an Eco-Friendly Hero"

Why on earth am I watching this? Sometimes, I get lost in the TV home shopping screens.

For example, there are moments when sebum is extracted one by one from the bridge of a model's nose, which is enlarged to fill the screen, or when a shopping host passionately shows off her own garak-guksu-like skin after applying soap to her calves.

The unexpected combination of extraordinary product functionality, the wonders of the human body, and professional integrity is simply breathtaking.

Recently, a set of frying pans with a special coating on the triple bottom was added to my admiration list.

Even if you burn the stir-fried octopus seasoned with gochujang, it can be washed cleanly with just a splash of water. Even if you fry scrambled eggs and wheat pancakes right away, they move smoothly like curling stones in the frying pan.

I was absorbed in the screen with my mouth open.

As if the caption "continuous sellout" wasn't an exaggeration, one day on my way to work, I came across the very product that had been delivered to my neighbor's front door.

--- From "Aluminum: Even the Survivors Are in Pain"

The "How dare you!" ideology, or misogyny, which fails to accept women's subjective choices and decisions, is as toxic as acid throughout the world.

To say this would be a great disrespect to hydrogen, which has lit up the night sky with stars and supported life on Earth with its blazing sun for 13.8 billion years.

Do they realize that using such a noble element for such a shameful act of ruining the lives of other human beings is a "cosmic crime of defamation" that tarnishes the reputation of hydrogen, the first element in the universe?

--- From "Hydrogen: The Ugly Heart That Commits Mountain Terrorism"

From the declaration of martial law on December 3, 2024, to the final impeachment of the president on April 4, 2025, for over 100 days, a literal "chaos of chaos" unfolded in our brains.

By repeatedly experiencing events that triggered intense emotional anger, the amygdala, hippocampus, and neurons became more active and connected than ever before, 'imprinting' historical moments on the brain.

However, other precious memories were lost due to severe sleep deprivation and anxiety.

I was able to remember the faces of the military generals, such as the counterintelligence officers and the water defense officers, whom I had never needed to know in my life, but I completely forgot about the live broadcast schedule for the Nobel Prize in Literature award ceremony for author Han Kang, which I had been waiting for.

More vivid than the memories of the trip to Jeju Island with my mother after 20 years, the news footage of the failed attempt to arrest the president that I saw in the living room of my hotel there was vivid.

--- From "Calcium: Life and History Engraved in the Bones"

Not everyone can become a fighter in the face of massive violence and injustice.

But at least I can reflect on what my actions or inactions mean.

History tells us what can happen when we give up even this.

The Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum sells magnets with messages from Holocaust survivors.

The words of a survivor named Roman Kent come to mind.

It is one more commandment added to the Ten Commandments of the Bible.

“Eleventh Commandment: You should never ever be a bystander.”

--- From "Nitrogen: The Human Face in an Extermination Camp"

Publisher's Review

*** Highly recommended by Byun Jin-kyung, Lee Gi-byeong, and Hong Eun-jeon! ***

If Italy has Primo Levi, South Korea has Kim Myung-hee.

_Byeon Jin-kyung (Director of SisaIN)

The breadth and depth of the stories drawn from the elements are jaw-dropping.

_Lee Gi-byeong (medical anthropologist)

Mysterious, shocking, and above all, lovely.

_Hong Eun-jeon (human rights and animal rights activist)

On Primo Levi's laboratory

A new periodic table of human society, remixed by social scientist Kim Myung-hee.

Read the irony of civilization and history through 18 elements!

For many, the periodic table may be nothing more than a memory table, reminiscent of those boring chemistry classes where we recited “Helbebium carbonate…”

For social scientist Kim Myung-hee, the periodic table is remembered as a book by Primo Levi, a Jewish Holocaust survivor, chemist, and writer.

The series, which began at the recommendation of SisaIN’s Director Jin-kyung Byun, was an homage to Levi’s “Periodic Table” and a process of answering the question, “How different and similar are the elements I give meaning to from the 21 elements of life selected by Primo Levi?”

“I have never been swept up in the turbulent waves of history as Primo Levi was, nor have I ever faced such profound existential and ethical questions, but I too have had a ‘story to tell.’

“The story is not about me personally, but about the world and people I have studied, witnessed, and been in solidarity with as a science student, health researcher, and citizen with a lot of passion.”

- 〈Prologue〉

If Primo Levi, in his "Mercury" piece, showed "the madness of a closed community, the pre-modern moral sense, and the eccentricities of people who find it difficult to distinguish the symptoms of mercury poisoning," Kim Myung-hee reveals in detail how a 15-year-old boy who was making thermometers in a factory died from "the fantastic alchemy of corporations and government" that is more lethal than the toxicity of mercury.

When Primo Levi recalls his ancestors, “the respectable Jews of Piedmont,” in the inert nature of “argon,” Kim Myung-hee recalls “today’s atomized modern man.”

If "The Periodic Table" is a memoir by a Holocaust survivor, rich in literary quality, from childhood stories to reflections on humanity, "The Irony of the Periodic Table," which arrived to us exactly 50 years later, can be said to be a periodic table of human society newly mixed on Levy's experimental table.

Kim Myung-hee, who has been studying the health rights of workers and the socially disadvantaged and the social factors of disease, wanted to “illuminate how elements connect seemingly unrelated entities and events” by extracting stories from “extremely insignificant elements born from the Big Bang, without emotions or will,” and letting those stories flow to people.

Through a novel approach that analyzes the 18 elements of the periodic table using social science methodology, it keenly captures the contradictions of civilization and humanity hidden within the scientific order.

“By combining the complex interactions of elements, science and literature, myth and history, occupational diseases and infectious diseases, technological progress and inequality, discrimination and solidarity” (Hong Eun-jeon), he closely explores the traces that the foundation of all things has left on human ethics and social structures.

“Depending on the choices humans make and what they value, certain elements can become either saviors or destroyers,” the author reveals, step by step, based on data he personally researched and analyzed, as well as various domestic and international literature and research cases.

The authors who wrote the recommendations for this book, which stands out for its weighty subject matter and unique structure, surprisingly unanimously praised the “entertainment of the story.”

The researcher's writing possesses a level of popularity and readability that is far beyond the scope of a typical academic paper, thanks to a diverse range of materials, including science fiction, Netflix, home shopping, martial arts novels, and mythology, that straddle the line between solid scientific knowledge and accurate data.

What difference does the element make when it combines with humans?

Can science be free from society?

He entered medical school, but as soon as he entered, he was “picked” by his seniors in the student movement and became active as a “demonstrator,” and he began to doubt himself, thinking, “What’s the point of being a doctor when the world is like this?”

One day, while attending a Wonjin Rayon meeting, the author learned of a field called preventive medicine through the recommendation of a senior, and this determined his life path.

The author recalls that his career in social medicine, which seeks to identify the causes of individual illness in social structures, was “the smallest of the many legacies left behind by the Wonjin Rayon struggle.”

The story of 'Hwang' begins in the 'funeral struggle' of Wonjin Rayon that lasted 137 days.

Sulfur, which is not toxic in itself and is used in various fields of daily life, and is a major component of medicines such as penicillin and fertilizers, how did it become the 'god of death'?

The author points out cases of domestic and foreign companies that continued to relocate their production bases and neglect their workers despite knowing the toxicity of carbon disulfide, a compound of sulfur and carbon, and criticizes, “The pain of workers who fought alone against an unknown disease and workers who ended their lives by suicide after suffering from serious mental illness was something they should not have had to experience in the first place.”

The episode that concludes the story of Hwang is a deliberate irony that is refreshing and meaningful in itself, revealing the author's knowledge (science), taste (SF), and social consciousness.

“One day, a person who had been diligently preaching the word of God to me on the subway asked me, “Don’t you want to go to heaven?” when I refused to listen.

I answered.

“No, I want to go to hell.” He ran to the next compartment.

If it is the infinite power that mankind has dreamed of, the unquenchable fire of hell, there is no reason to refuse it.

Top scientists like Feynman, Hawking, Higgs, Schrödinger, and Einstein are likely already there, having committed the sin of not believing in God, and are likely already developing a technological civilization by utilizing perpetual motion.

There's no need to worry about getting bored, because there are many fun writers like Douglas Adams, Kurt Vonnegut, and many other science fiction writers who have already gone before me and established themselves.

Wouldn't it be wonderful if you could burn the sulfurous hellfire with its mystical blue flames with your cheerful fellow citizens, in a pleasant environment, without worrying about occupational diseases?

- 〈Hwang: No, I'm going to hell〉

Meanwhile, the protagonist of the 'lead' story is geochemist Claire Patterson.

With an obsessive effort, he creates the most perfect 'clean room' in history, and finally succeeds in estimating the age of the Earth by measuring the 'pure' lead content in meteorites that fell during the Earth's formation.

But here the story takes an unexpected turn.

He wondered where the ubiquitous lead came from, and after examining various hypotheses, he concluded that leaded gasoline, which appeared in 1923, was closely related to lead contamination.

The oil industry even employs contract scientists to sabotage his research, but Patterson analyzes the deep seas of the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, the North and South Poles, snow-capped mountains, volcanic craters, and even human remains and mummies to prove his hypothesis.

The story doesn't end there, and extends to the water pipes of Flint, USA.

The Flint water crisis, a poor city of color whose water supply was supplied by contaminated lead pipes, vividly illustrates the discrimination that can arise when neutral elements combine with humans, while also raising the unavoidable question, "Can science be free from society?"

To Nitrogen, who was crying on the planet Tralfamador

We still have words of comfort left.

Shortly after the end of World War II, nitrogen, who had served involuntarily as a Nazi guard and doctor, weeps among the chemical elements gathered on the planet Tralfamador.

The "Nitrogen" chapter, which begins with a scene from Kurt Vonnegut's novel "Timequake," is the climax of the book, where the incomprehensible irony of humanity is most powerfully revealed.

As we follow the journey of how nitrogen, which has played a brilliant role in solving humanity's food problem, came to be used to massacre people, as the author says, "a sense of wonder comes before fear or sadness."

“Even when I personally visited the Buchenwald concentration camp in Germany and the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp in Poland, I felt more puzzlement than fear or sadness.

"What on earth was this, this much work? What was the essence of the diligence and efficiency that went into transporting people scattered across Europe by train, connecting the railway to the camp's front yard to expedite the process even a little, meticulously classifying and labeling the numerous prisoners according to their characteristics, building separate gas chambers to kill so many people simultaneously and quickly, coating the inside of the carts carrying the bodies to prevent residue, and installing elevators to transport the bodies from the gas chambers to the crematorium entrance?"

- From “Nitrogen: The Human Face in an Extermination Camp”

But this book doesn't just talk about the dark side of humanity.

“Nitrogen was in the bodies of not only the murderers and bystanders, but also those who resisted injustice where there was no hope of success, who showed humanity even in the most dangerous and miserable moments, and who stood tall to protect their own conscience where no one was watching,” he said, comforting Nitrogen, who was weeping on the planet Tralfamador.

In Gwangju in 1980, when martial law forces took control of the city and public transportation was cut off, we are struck by the sight of people risking their lives to donate blood, “standing in a long, winding line from the entrance of the blood bank to the main gate of the hospital,” and by the small act of a scientist who “always held something in both hands when leaving the house” to avoid saluting Hitler and the Nazis. This is probably because we still have hope for humanity.

Human history is also a record of how we have treated others.

The 18 elements contained in the book are the basic elements of matter that contain interesting scientific knowledge in themselves, but they are also 'witnesses' who testify to what happens when humans objectify other humans.

As discussed in the "Iron" section, a "vampiric" society that sucks the blood of the people, a "blood-selling" society where even blood is traded as a commodity, and a donation society where people help strangers through voluntary "blood donation" without any special compensation are all destined to face different futures.

The map of the body, othering, and solidarity drawn by the author on the periodic table not only provides the intellectual pleasure of reading society as a material of natural science, but also provides an opportunity to reflect on “what meaning my actions or inactions have.”

It is up to the readers to answer how similar and different the irony contained in Primo Levi's "Periodic Table" published in 1975 is and how different the "Periodic Table Irony" of 2025 is.

If Italy has Primo Levi, South Korea has Kim Myung-hee.

_Byeon Jin-kyung (Director of SisaIN)

The breadth and depth of the stories drawn from the elements are jaw-dropping.

_Lee Gi-byeong (medical anthropologist)

Mysterious, shocking, and above all, lovely.

_Hong Eun-jeon (human rights and animal rights activist)

On Primo Levi's laboratory

A new periodic table of human society, remixed by social scientist Kim Myung-hee.

Read the irony of civilization and history through 18 elements!

For many, the periodic table may be nothing more than a memory table, reminiscent of those boring chemistry classes where we recited “Helbebium carbonate…”

For social scientist Kim Myung-hee, the periodic table is remembered as a book by Primo Levi, a Jewish Holocaust survivor, chemist, and writer.

The series, which began at the recommendation of SisaIN’s Director Jin-kyung Byun, was an homage to Levi’s “Periodic Table” and a process of answering the question, “How different and similar are the elements I give meaning to from the 21 elements of life selected by Primo Levi?”

“I have never been swept up in the turbulent waves of history as Primo Levi was, nor have I ever faced such profound existential and ethical questions, but I too have had a ‘story to tell.’

“The story is not about me personally, but about the world and people I have studied, witnessed, and been in solidarity with as a science student, health researcher, and citizen with a lot of passion.”

- 〈Prologue〉

If Primo Levi, in his "Mercury" piece, showed "the madness of a closed community, the pre-modern moral sense, and the eccentricities of people who find it difficult to distinguish the symptoms of mercury poisoning," Kim Myung-hee reveals in detail how a 15-year-old boy who was making thermometers in a factory died from "the fantastic alchemy of corporations and government" that is more lethal than the toxicity of mercury.

When Primo Levi recalls his ancestors, “the respectable Jews of Piedmont,” in the inert nature of “argon,” Kim Myung-hee recalls “today’s atomized modern man.”

If "The Periodic Table" is a memoir by a Holocaust survivor, rich in literary quality, from childhood stories to reflections on humanity, "The Irony of the Periodic Table," which arrived to us exactly 50 years later, can be said to be a periodic table of human society newly mixed on Levy's experimental table.

Kim Myung-hee, who has been studying the health rights of workers and the socially disadvantaged and the social factors of disease, wanted to “illuminate how elements connect seemingly unrelated entities and events” by extracting stories from “extremely insignificant elements born from the Big Bang, without emotions or will,” and letting those stories flow to people.

Through a novel approach that analyzes the 18 elements of the periodic table using social science methodology, it keenly captures the contradictions of civilization and humanity hidden within the scientific order.

“By combining the complex interactions of elements, science and literature, myth and history, occupational diseases and infectious diseases, technological progress and inequality, discrimination and solidarity” (Hong Eun-jeon), he closely explores the traces that the foundation of all things has left on human ethics and social structures.

“Depending on the choices humans make and what they value, certain elements can become either saviors or destroyers,” the author reveals, step by step, based on data he personally researched and analyzed, as well as various domestic and international literature and research cases.

The authors who wrote the recommendations for this book, which stands out for its weighty subject matter and unique structure, surprisingly unanimously praised the “entertainment of the story.”

The researcher's writing possesses a level of popularity and readability that is far beyond the scope of a typical academic paper, thanks to a diverse range of materials, including science fiction, Netflix, home shopping, martial arts novels, and mythology, that straddle the line between solid scientific knowledge and accurate data.

What difference does the element make when it combines with humans?

Can science be free from society?

He entered medical school, but as soon as he entered, he was “picked” by his seniors in the student movement and became active as a “demonstrator,” and he began to doubt himself, thinking, “What’s the point of being a doctor when the world is like this?”

One day, while attending a Wonjin Rayon meeting, the author learned of a field called preventive medicine through the recommendation of a senior, and this determined his life path.

The author recalls that his career in social medicine, which seeks to identify the causes of individual illness in social structures, was “the smallest of the many legacies left behind by the Wonjin Rayon struggle.”

The story of 'Hwang' begins in the 'funeral struggle' of Wonjin Rayon that lasted 137 days.

Sulfur, which is not toxic in itself and is used in various fields of daily life, and is a major component of medicines such as penicillin and fertilizers, how did it become the 'god of death'?

The author points out cases of domestic and foreign companies that continued to relocate their production bases and neglect their workers despite knowing the toxicity of carbon disulfide, a compound of sulfur and carbon, and criticizes, “The pain of workers who fought alone against an unknown disease and workers who ended their lives by suicide after suffering from serious mental illness was something they should not have had to experience in the first place.”

The episode that concludes the story of Hwang is a deliberate irony that is refreshing and meaningful in itself, revealing the author's knowledge (science), taste (SF), and social consciousness.

“One day, a person who had been diligently preaching the word of God to me on the subway asked me, “Don’t you want to go to heaven?” when I refused to listen.

I answered.

“No, I want to go to hell.” He ran to the next compartment.

If it is the infinite power that mankind has dreamed of, the unquenchable fire of hell, there is no reason to refuse it.

Top scientists like Feynman, Hawking, Higgs, Schrödinger, and Einstein are likely already there, having committed the sin of not believing in God, and are likely already developing a technological civilization by utilizing perpetual motion.

There's no need to worry about getting bored, because there are many fun writers like Douglas Adams, Kurt Vonnegut, and many other science fiction writers who have already gone before me and established themselves.

Wouldn't it be wonderful if you could burn the sulfurous hellfire with its mystical blue flames with your cheerful fellow citizens, in a pleasant environment, without worrying about occupational diseases?

- 〈Hwang: No, I'm going to hell〉

Meanwhile, the protagonist of the 'lead' story is geochemist Claire Patterson.

With an obsessive effort, he creates the most perfect 'clean room' in history, and finally succeeds in estimating the age of the Earth by measuring the 'pure' lead content in meteorites that fell during the Earth's formation.

But here the story takes an unexpected turn.

He wondered where the ubiquitous lead came from, and after examining various hypotheses, he concluded that leaded gasoline, which appeared in 1923, was closely related to lead contamination.

The oil industry even employs contract scientists to sabotage his research, but Patterson analyzes the deep seas of the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, the North and South Poles, snow-capped mountains, volcanic craters, and even human remains and mummies to prove his hypothesis.

The story doesn't end there, and extends to the water pipes of Flint, USA.

The Flint water crisis, a poor city of color whose water supply was supplied by contaminated lead pipes, vividly illustrates the discrimination that can arise when neutral elements combine with humans, while also raising the unavoidable question, "Can science be free from society?"

To Nitrogen, who was crying on the planet Tralfamador

We still have words of comfort left.

Shortly after the end of World War II, nitrogen, who had served involuntarily as a Nazi guard and doctor, weeps among the chemical elements gathered on the planet Tralfamador.

The "Nitrogen" chapter, which begins with a scene from Kurt Vonnegut's novel "Timequake," is the climax of the book, where the incomprehensible irony of humanity is most powerfully revealed.

As we follow the journey of how nitrogen, which has played a brilliant role in solving humanity's food problem, came to be used to massacre people, as the author says, "a sense of wonder comes before fear or sadness."

“Even when I personally visited the Buchenwald concentration camp in Germany and the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp in Poland, I felt more puzzlement than fear or sadness.

"What on earth was this, this much work? What was the essence of the diligence and efficiency that went into transporting people scattered across Europe by train, connecting the railway to the camp's front yard to expedite the process even a little, meticulously classifying and labeling the numerous prisoners according to their characteristics, building separate gas chambers to kill so many people simultaneously and quickly, coating the inside of the carts carrying the bodies to prevent residue, and installing elevators to transport the bodies from the gas chambers to the crematorium entrance?"

- From “Nitrogen: The Human Face in an Extermination Camp”

But this book doesn't just talk about the dark side of humanity.

“Nitrogen was in the bodies of not only the murderers and bystanders, but also those who resisted injustice where there was no hope of success, who showed humanity even in the most dangerous and miserable moments, and who stood tall to protect their own conscience where no one was watching,” he said, comforting Nitrogen, who was weeping on the planet Tralfamador.

In Gwangju in 1980, when martial law forces took control of the city and public transportation was cut off, we are struck by the sight of people risking their lives to donate blood, “standing in a long, winding line from the entrance of the blood bank to the main gate of the hospital,” and by the small act of a scientist who “always held something in both hands when leaving the house” to avoid saluting Hitler and the Nazis. This is probably because we still have hope for humanity.

Human history is also a record of how we have treated others.

The 18 elements contained in the book are the basic elements of matter that contain interesting scientific knowledge in themselves, but they are also 'witnesses' who testify to what happens when humans objectify other humans.

As discussed in the "Iron" section, a "vampiric" society that sucks the blood of the people, a "blood-selling" society where even blood is traded as a commodity, and a donation society where people help strangers through voluntary "blood donation" without any special compensation are all destined to face different futures.

The map of the body, othering, and solidarity drawn by the author on the periodic table not only provides the intellectual pleasure of reading society as a material of natural science, but also provides an opportunity to reflect on “what meaning my actions or inactions have.”

It is up to the readers to answer how similar and different the irony contained in Primo Levi's "Periodic Table" published in 1975 is and how different the "Periodic Table Irony" of 2025 is.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: November 25, 2025

- Page count, weight, size: 288 pages | 450g | 140*215*17mm

- ISBN13: 9791155251843

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)