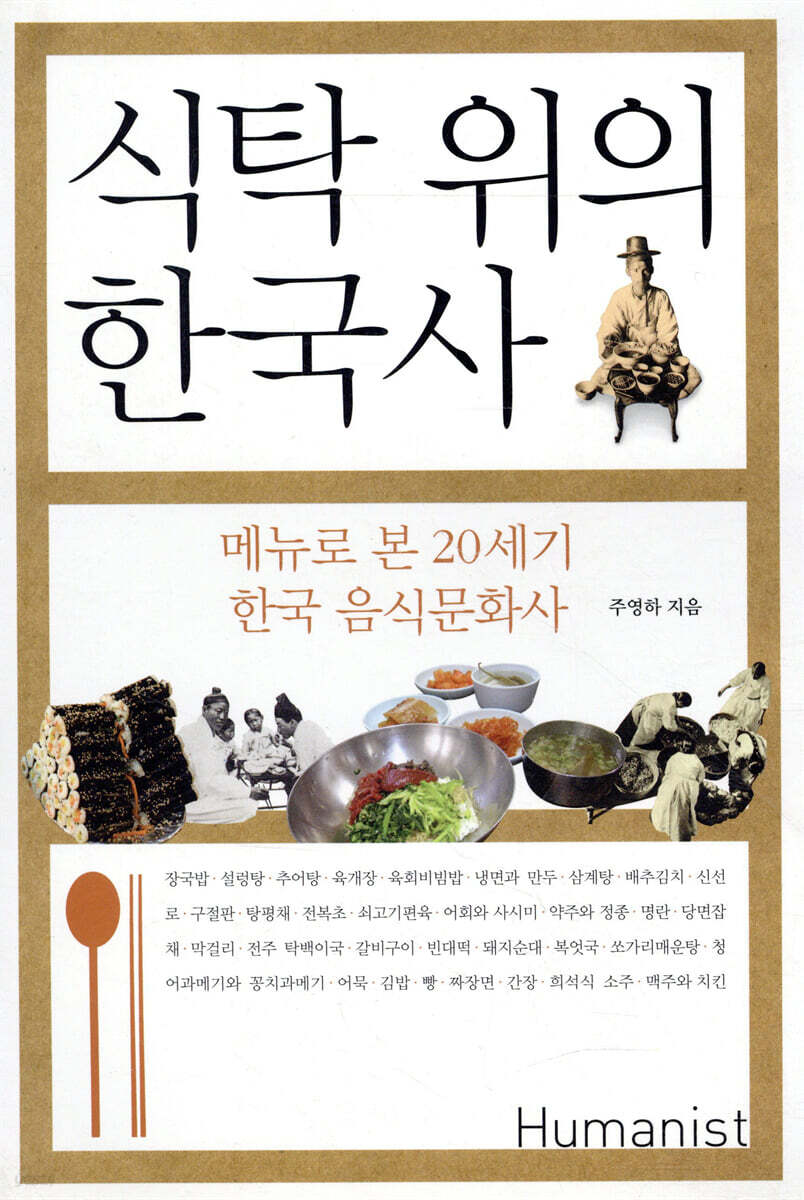

Korean History on the Table

|

Description

Book Introduction

- A word from MD

-

Food we've eaten over the past 100 yearsHow has Korean cuisine evolved over the course of modern Korean history? Food humanist Joo Young-ha explores the history and transformation of Korean society through the menus that have graced our tables over the past century.

A look at the history of 20th-century food on the Korean Peninsula, from the colonial period to the modern era and the wave of rapid industrialization.

What have we been eating for the past 100 years?

From the modern person's dining table to the modern person's dining table,

A Look at 20th-Century Korean Food Culture Through Menus

Korean food is considered a part of Koreans' daily lives and a cultural heritage that symbolizes Korea.

But is Korean food truly a cultural heritage that has remained unchanged since the Joseon Dynasty? Professor Joo Young-ha, a food humanist at the Academy of Korean Studies, points out the dangers of a social climate that treats food as history and regards history as the answer. He argues that, rather than asking, "What is the origin of Korean food?", the more important question is, "What have Koreans eaten and how?"

Because if you know what an individual or a society ate and how they lived, you can see the history of that society.

In particular, he says that in order to understand today's Korean food culture, we must pay attention to the changes of the 20th century.

A characteristic of 20th-century Korean food culture is the emergence of the modern restaurant industry, which transformed diners into customers. This book, "Korean History on the Table," tells the history of Korean food culture through the menus that have been served on Korean tables over the past 100 years.

By not only tracing the origins and microscopic details of how and why food on the menu has changed over time, but also analyzing the macroscopic impact of political, economic, social, and cultural changes on food culture, we gain insight into the historical and evolving nature of food in our daily lives.

This book goes beyond a narrative of individual menu items to explain the historical implications of the times when those menu items became popular. Rather than providing a definitive answer to the history of Korean food, it suggests a perspective on Korean society through food.

“Because biological food contains matter, but cultural food contains thoughts.”

This book explains the original form and evolution of commonly known food menus, but this evolutionary process can never be explained by the food itself, and in particular, it cannot be said to have been invented by the person who created the food.

It has to do with the world that Koreans experienced while living on the Korean Peninsula in the 20th century.

Some foods are deeply imbued with political relations and economic contexts, and even foods invented by chance have inherent social and cultural conditions surrounding them.

In this respect, a critical perspective is necessary to approach the history of food.

The periodization of 20th-century Korean food history will serve as a guide.

From the modern person's dining table to the modern person's dining table,

A Look at 20th-Century Korean Food Culture Through Menus

Korean food is considered a part of Koreans' daily lives and a cultural heritage that symbolizes Korea.

But is Korean food truly a cultural heritage that has remained unchanged since the Joseon Dynasty? Professor Joo Young-ha, a food humanist at the Academy of Korean Studies, points out the dangers of a social climate that treats food as history and regards history as the answer. He argues that, rather than asking, "What is the origin of Korean food?", the more important question is, "What have Koreans eaten and how?"

Because if you know what an individual or a society ate and how they lived, you can see the history of that society.

In particular, he says that in order to understand today's Korean food culture, we must pay attention to the changes of the 20th century.

A characteristic of 20th-century Korean food culture is the emergence of the modern restaurant industry, which transformed diners into customers. This book, "Korean History on the Table," tells the history of Korean food culture through the menus that have been served on Korean tables over the past 100 years.

By not only tracing the origins and microscopic details of how and why food on the menu has changed over time, but also analyzing the macroscopic impact of political, economic, social, and cultural changes on food culture, we gain insight into the historical and evolving nature of food in our daily lives.

This book goes beyond a narrative of individual menu items to explain the historical implications of the times when those menu items became popular. Rather than providing a definitive answer to the history of Korean food, it suggests a perspective on Korean society through food.

“Because biological food contains matter, but cultural food contains thoughts.”

This book explains the original form and evolution of commonly known food menus, but this evolutionary process can never be explained by the food itself, and in particular, it cannot be said to have been invented by the person who created the food.

It has to do with the world that Koreans experienced while living on the Korean Peninsula in the 20th century.

Some foods are deeply imbued with political relations and economic contexts, and even foods invented by chance have inherent social and cultural conditions surrounding them.

In this respect, a critical perspective is necessary to approach the history of food.

The periodization of 20th-century Korean food history will serve as a guide.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

20th Century Korean History on the Table Prepared by a Food Humanist

Prologue: How to Divide the History of Korean Food into Periods

Part 1: The Opening of Ports: A Variety of Foreign Foods Arriving

Daibutsu Hotel and Junghwaru in Jemulpo

Westerners eating in Seoul

Jeongdong Flower Lady Son Tak and Son Tak Hotel

Japanese immigration and the influx of the food industry

Part 2: Noodle House

0 The oldest restaurant, noodle restaurant

Eat lots!

A bowl of meal, Jang Guk Bap

1 A common meal, Seolleongtang

The origin of seolleongtang

Becoming a Seoul landmark

Seolleongtang that has lost its flavor

2 Chueotang that captivated autumn diners

Chueotang restaurant scene

Chueotang recipe

All year round, I only eat farmed loach.

3 variations of yukgaejang

The long-standing pros and cons surrounding the opening

From Gaejang to Yukgaejang

4 The Secret of Yukhoe Bibimbap

The original form of bibimbap

The Birth of Yukhoe Bibimbap

Gochujang, a solidified seasoning for bibimbap

5 Myeonokjip's signature menu items, cold noodles and dumplings

Naengmyeon, from winter food to summer food

Naengmyeon + Ajinomoto = Mimi

Pyeonsu, a representative food of Gaeseong

The popularization of dumplings, a unique food made from wheat flour.

6. Samgyetang, a food created by modern times

Increased chicken consumption and chicken dishes

Samgyetang, which prioritizes ginseng over chicken

(Special Feature) Kimchi: From Joseon Cabbage to Tiger Cabbage

Even if you have everything, if you don't have kimchi...

The history of cabbage kimchi

Part 3 Joseon Cooking House

0 The Birth of a High-End Restaurant, Joseon Restaurant

The story of the original Joseon cuisine

Let's go to Myeongwol Gwan!

1. Shinseonro, the symbol of Joseon cuisine

The best restaurant table setting, Shinsunro

Sinseonro is the name of a dish, not a food.

The taste of fresh roe adds a piping hot flavor

Was the 2-section version a royal dish?

Uncommon tableware, Gujeolpan

The core of the phrase is the wheat pancake

3. Tangpyeongchae, the basic dish of a Korean meal

Food derived from King Yeongjo's Tangpyeong policy?

Tangpyeongchae has a light taste

4 Until Jeonbokcho arrives at the restaurant's table

Jeonbokcho served on the table at Myeongwol Gwan during a royal banquet

From dried abalone to canned abalone

Wild abalone with dried seeds due to mass harvesting

5 Beef Boneless, the ultimate menu item at a high-end restaurant

Yangjimeori pyeonyuk, upjin pyeonyuk, jeyuk pyeonyuk, ox head pyeonyuk

The policy-driven trend of pork dishes

6 From Korean-style raw fish to Japanese-style sashimi

The difference between sashimi and raw fish

Colonial-era sashimi recipe

7. Yakju, pushed out by Jeongjong

Yakju, a high-class liquor enjoyed by noble families

Japanese Cheongju and Jeongjong advance into the Korean Peninsula

A liquor that no one knows about anymore

The story of how Myeongran went to Fukuoka

Myeongran jeot eaten in winter

Myeongran crossed over to the empire

(Special Feature) Dangmyeon Japchae: A Collaboration Between Korea, China, and Japan

Traditional Chinese noodles

Dangmyeon Japchae seasoned with soy sauce

(Special Feature) People of Yoriok, Gisaengs and Boys

The flower of Joseon cuisine, gisaeng

Boy's hardships

Part 4 Daepotjip

0 A refuge for the weary common people, Daepotjip

A tavern that was popular before the Daepotjip

From tavern to bar

1 Makgeolli, a snack at a large restaurant

Makgeolli, the drink of farmers and workers

Government intervenes in makgeolli

The best of the two wine countries, Jeonju Takbaekiguk

Jeonju's specialty, takbaek-i-guk

If you boil bean sprouts until soft, sprinkle some salt on them, and drink it…

It tastes best when you buy it and eat it

3. Grilled ribs are originally a menu item at a large restaurant.

The oil is finely chopped, the meat is tender and tasty.

The emergence of a street of galbi restaurants

Split consumer base

4. Bindaetteok, an inexpensive snack that started at a stall

Bindaetteok, the rice cake of the poor

Bindaetteok history

The most developed food since liberation

5. Pork Sundae, From a High-End Restaurant to a Restaurant Menu

Various types of sundae, including beef, pork, dog, and fish

The trend of cheap sundae (pork sausage)

6. Until Bok-eot-guk obtains citizenship

Pufferfish that scholars risked their lives to eat

The story of a man who died from eating puffer fish discarded by a Japanese person

Bok-eot-guk finally gets citizenship

7 Spicy Sogari Stew, a health food that has become a drinker's delicacy

Tonic food, gyeo-eo and geumrin-eo

From sogari jjijim to sogari spicy stew

From wild to farmed

(Special Feature) Jang In-yeong, a Korean brewer during the colonial period, and Cheonil Brewery

(Special Feature) Mackerel and Anchovy Gwamegi

Part 5: After Liberation: The Hybridization of Food and the Globalization of Restaurants

0 The constant evolution of restaurants and menus

1 Japanese food that has become established as Korean food

The original name for fish cake is kamaboko

Kimbap, which originated from Japanese cuisine

2 Flour restaurants booming

Modern milling industry that began during the colonial period

From bread vendors to franchise bakeries

Jjajangmyeon becomes a popular food

The birth of Korean-style jajangmyeon

Free flour supply and promotion of mixed flour

A new evolution of flour foods

3 Growth and the Backstreets of the Food Industry

The transformation of factory-made soy sauce

The golden age of diluted soju

The emergence of large food companies and their monopolies

4 McDonaldization of Korean Restaurants

From a pub to 'chicken and beer'

Franchising of Korean restaurants

Epilogue: Critical Food Studies: A New Perspective on Korean Society

Notes in the text

Search

Prologue: How to Divide the History of Korean Food into Periods

Part 1: The Opening of Ports: A Variety of Foreign Foods Arriving

Daibutsu Hotel and Junghwaru in Jemulpo

Westerners eating in Seoul

Jeongdong Flower Lady Son Tak and Son Tak Hotel

Japanese immigration and the influx of the food industry

Part 2: Noodle House

0 The oldest restaurant, noodle restaurant

Eat lots!

A bowl of meal, Jang Guk Bap

1 A common meal, Seolleongtang

The origin of seolleongtang

Becoming a Seoul landmark

Seolleongtang that has lost its flavor

2 Chueotang that captivated autumn diners

Chueotang restaurant scene

Chueotang recipe

All year round, I only eat farmed loach.

3 variations of yukgaejang

The long-standing pros and cons surrounding the opening

From Gaejang to Yukgaejang

4 The Secret of Yukhoe Bibimbap

The original form of bibimbap

The Birth of Yukhoe Bibimbap

Gochujang, a solidified seasoning for bibimbap

5 Myeonokjip's signature menu items, cold noodles and dumplings

Naengmyeon, from winter food to summer food

Naengmyeon + Ajinomoto = Mimi

Pyeonsu, a representative food of Gaeseong

The popularization of dumplings, a unique food made from wheat flour.

6. Samgyetang, a food created by modern times

Increased chicken consumption and chicken dishes

Samgyetang, which prioritizes ginseng over chicken

(Special Feature) Kimchi: From Joseon Cabbage to Tiger Cabbage

Even if you have everything, if you don't have kimchi...

The history of cabbage kimchi

Part 3 Joseon Cooking House

0 The Birth of a High-End Restaurant, Joseon Restaurant

The story of the original Joseon cuisine

Let's go to Myeongwol Gwan!

1. Shinseonro, the symbol of Joseon cuisine

The best restaurant table setting, Shinsunro

Sinseonro is the name of a dish, not a food.

The taste of fresh roe adds a piping hot flavor

Was the 2-section version a royal dish?

Uncommon tableware, Gujeolpan

The core of the phrase is the wheat pancake

3. Tangpyeongchae, the basic dish of a Korean meal

Food derived from King Yeongjo's Tangpyeong policy?

Tangpyeongchae has a light taste

4 Until Jeonbokcho arrives at the restaurant's table

Jeonbokcho served on the table at Myeongwol Gwan during a royal banquet

From dried abalone to canned abalone

Wild abalone with dried seeds due to mass harvesting

5 Beef Boneless, the ultimate menu item at a high-end restaurant

Yangjimeori pyeonyuk, upjin pyeonyuk, jeyuk pyeonyuk, ox head pyeonyuk

The policy-driven trend of pork dishes

6 From Korean-style raw fish to Japanese-style sashimi

The difference between sashimi and raw fish

Colonial-era sashimi recipe

7. Yakju, pushed out by Jeongjong

Yakju, a high-class liquor enjoyed by noble families

Japanese Cheongju and Jeongjong advance into the Korean Peninsula

A liquor that no one knows about anymore

The story of how Myeongran went to Fukuoka

Myeongran jeot eaten in winter

Myeongran crossed over to the empire

(Special Feature) Dangmyeon Japchae: A Collaboration Between Korea, China, and Japan

Traditional Chinese noodles

Dangmyeon Japchae seasoned with soy sauce

(Special Feature) People of Yoriok, Gisaengs and Boys

The flower of Joseon cuisine, gisaeng

Boy's hardships

Part 4 Daepotjip

0 A refuge for the weary common people, Daepotjip

A tavern that was popular before the Daepotjip

From tavern to bar

1 Makgeolli, a snack at a large restaurant

Makgeolli, the drink of farmers and workers

Government intervenes in makgeolli

The best of the two wine countries, Jeonju Takbaekiguk

Jeonju's specialty, takbaek-i-guk

If you boil bean sprouts until soft, sprinkle some salt on them, and drink it…

It tastes best when you buy it and eat it

3. Grilled ribs are originally a menu item at a large restaurant.

The oil is finely chopped, the meat is tender and tasty.

The emergence of a street of galbi restaurants

Split consumer base

4. Bindaetteok, an inexpensive snack that started at a stall

Bindaetteok, the rice cake of the poor

Bindaetteok history

The most developed food since liberation

5. Pork Sundae, From a High-End Restaurant to a Restaurant Menu

Various types of sundae, including beef, pork, dog, and fish

The trend of cheap sundae (pork sausage)

6. Until Bok-eot-guk obtains citizenship

Pufferfish that scholars risked their lives to eat

The story of a man who died from eating puffer fish discarded by a Japanese person

Bok-eot-guk finally gets citizenship

7 Spicy Sogari Stew, a health food that has become a drinker's delicacy

Tonic food, gyeo-eo and geumrin-eo

From sogari jjijim to sogari spicy stew

From wild to farmed

(Special Feature) Jang In-yeong, a Korean brewer during the colonial period, and Cheonil Brewery

(Special Feature) Mackerel and Anchovy Gwamegi

Part 5: After Liberation: The Hybridization of Food and the Globalization of Restaurants

0 The constant evolution of restaurants and menus

1 Japanese food that has become established as Korean food

The original name for fish cake is kamaboko

Kimbap, which originated from Japanese cuisine

2 Flour restaurants booming

Modern milling industry that began during the colonial period

From bread vendors to franchise bakeries

Jjajangmyeon becomes a popular food

The birth of Korean-style jajangmyeon

Free flour supply and promotion of mixed flour

A new evolution of flour foods

3 Growth and the Backstreets of the Food Industry

The transformation of factory-made soy sauce

The golden age of diluted soju

The emergence of large food companies and their monopolies

4 McDonaldization of Korean Restaurants

From a pub to 'chicken and beer'

Franchising of Korean restaurants

Epilogue: Critical Food Studies: A New Perspective on Korean Society

Notes in the text

Search

Publisher's Review

Pre-modern home cooking has become established as a restaurant menu with a consistent taste and serving style through the 20th century.

The first modern restaurant, the noodle house; the Joseon restaurant, a variation of the Japanese-style high-class restaurant; the Daepotjip, which filled the bellies of the common people with meals and snacks during the industrialization period; the main menus of the new restaurants born through globalization have been popular depending on the consumer base and the time period.

This book microscopically examines the origins and evolution of 34 food menus that have driven the modern restaurant industry, including seolleongtang, galbi, shinseonro, bindaetteok, and jajangmyeon, while simultaneously presenting new possibilities for "critical food studies" through macroscopic discourse analysis of political, economic, social, and cultural changes.

By following the sharp interpretations that penetrate the flow of time through interdisciplinary research that crosses the theories and methods of cultural anthropology, folklore, history, and sociology based on abundant historical materials such as newspapers, magazines, advertisements, and old documents, you can vividly restore the lives and cultural history of the people of the time, allowing you to encounter a new dimension of Korean history.

The task of examining the history of food is never easy.

Who can say with certainty that the cabbage we eat today is the same as the cabbage described in cookbooks from over a century ago? Could we recreate Joseon Dynasty cabbage kimchi, assuming the "cabbage" described in ancient texts is the same as today's cabbage? Even if we could recreate it similarly, would we be able to capture the thoughts of the people of that time in this dish? Simply listing the specifics of certain texts in a food history study is not history.

Only by uncovering why people at the time had no choice but to make and eat such food can we approach the history of that food.

The history of food is never a collection of episodes.

There is economics, politics, and society in it.

-From "Publishing a Book"

The history of food may seem trivial when approached from a macroscopic perspective.

But nothing encompasses both macro and micro history as much as the history of food.

Everyone, whether good or bad, must eat to live, and to eat, they engage in economic activities, social activities, and political activities.

So, if you know what an individual or a society ate and how they lived, you can see the history of that society.

In particular, the history of food experienced by the 'Korea' of the Korean Empire, which was incorporated into the 20th century world system, the colonial period, and the 'Korea' of the Republic of Korea is an exquisite combination of macrohistory and microhistory.

-From "Publishing a Book"

Interview with the Author

Hello, teacher.

In 2011, through “Food Humanities,” you continued the intersection of culinary studies and humanities, saying, “Food as a meal is part of everyday life, but food as culture and history is the humanities.” I am delighted to be able to meet you again after such a long time through a new book.

This book is titled “Korean History on the Table,” and I have a few questions about it.

1.

It is said that there is a common question that Koreans ask when they meet foreigners.

The question is whether you have ever tried kimchi or bulgogi. It seems that Koreans recognize that food is a cultural heritage that represents Korea.

But you said in this book that the origins of the modern Korean dining table can be found in the 20th century. Why did you focus on the history of 20th-century food?

- I think the reason Koreans tend to think of food itself as a cultural heritage is because after the 1988 Seoul Olympics, when foreign tourists began to flow in in earnest and took an interest in Korean food, Koreans also tried to give it meaning through their own identity as “Korean.”

In the process of strengthening Korean identity, academia and the media have tended to seek answers to the origins of Korean food in the Joseon Dynasty in order to give it a long history.

Food doesn't change as quickly as other aspects of food, clothing, and shelter, but even so, it is bound to continue to change within a cultural context.

Food, in particular, underwent rapid changes during the modern system introduced through the colonial period in the 20th century and the economic development and industrialization of the 1960s.

I thought that rather than emphasizing only traditional foods, we should acknowledge the changes in food throughout the 20th century.

Because only by acknowledging change can we understand our current state, and only by knowing this can we predict the future of Korean food.

By examining the changes in food throughout the 20th century, as well as the political and economic shifts contained within, we can consider the question of why we eat this food now.

2.

What is the concept of "hybridization" in Korean food that this book addresses, and what are the issues you wanted to suggest to Korean food culture?

- This book examines each menu to show that the food we eat today is not necessarily limited to old Korean food.

This problem awareness was also contained in the previous work, “Food Humanities,” but “Korean History on the Table” shows each food in more detail.

Korean food isn't just about old dishes.

Although there was movement of food ingredients during the Joseon Dynasty, since then, the movement of food ingredients to the periphery and around the world has become full-scale, so mixing is inevitable.

I believe that a more important question in Korean food culture than what “Korean food” is is what and how Koreans have been eating.

The food consumed in our society is a blend of diverse cultures. Can we single out only the traditional Korean foods and assign them the identity of "Korean food"? I believe the key is "hybridity."

Korean food is a combination of the continuation of old dishes and the intervention of new ones.

In other words, 20th-century Korean food is the result of a 'hybridization' of discourses on colonialism, traditionalism, nationalism, statism, the world system, and globalization.

In this context, we should examine foods that came from outside, foods that are old but have changed over the 20th century due to internal and external factors.

To do this, we need to look at Korean society and food culture from a humanistic perspective.

3.

In my previous work, “Food Humanities,” I presented “critical food studies,” and I see “Korean History on the Table” as a detailed work that addresses the issues raised in that book.

What is 'critical food studies', and how does reading Korean history through it differ from conventional food studies?

- Food science is the study of food, which is closest to us.

Because food consumption is such a personal thing, you might think it's just a matter of taste or voluntary choice.

It may seem difficult to connect today's food choices to grand political and economic discourses.

But think about when you buy groceries at the store, cook at home, or eat out.

Unless we are self-sufficient in all our food supplies, we will inevitably be in contact with national and global systems in the distribution of food ingredients.

The 20th century was a dynamic period of transition from pre-modern to modern times and integration into the global system, providing a prime example of how the small-scale food consumption of individuals transformed within the interconnectedness of vast nations and societies.

I can't say that everything is intertwined, but I wanted to reveal in this book the possibility that it is connected to the social and historical context.

In that sense, I wanted to organize the food produced and consumed by Koreans and the thoughts related to it, from small texts to grand discourses.

That is the task of reading Korean history through food.

Perhaps readers would find it easier to read if the food changes were organized chronologically, but from a food science perspective, I tried to show, through each menu, why people wanted to make and eat this food, why they went to restaurants, why the ingredients and food were sold, and finally, why the food became popular.

Through this, I wanted to provide an opportunity to look at Korea's 20th century through different eyes.

From this perspective, I propose ‘critical food studies.’

Critical food studies is a research perspective that goes beyond simply examining the origins of a food, its health benefits, or how it is made, and instead seeks to uncover the political, economic, social, and cultural implications that made its popularity possible.

The result of that specific research is this book.

4.

This book has a unique approach to reading ancient literature.

How did you primarily find and work with food literature?

- Existing food science researchers have only used cookbooks or references to dishes from the Joseon Dynasty as literature.

There are many cookbooks from the colonial period, but they were only used as reference and not considered traditional, so they were not given much weight.

I focused on cookbooks, magazines, and newspapers from the colonial period as sources for food studies.

These materials are digitized, making them easy to find and allowing you to explore a wide range of subjects.

However, the task of finding, filtering, and interpreting the numerous data about a single food takes as much effort as preparing a paper.

To explain food after liberation, I looked up statistical data from the time and read countless doctoral dissertations on food policy at the time currently being conducted in sociology and economics, which were very helpful.

Since the 1960s, the food data has been collected over 20 years through fieldwork, including interviews, local research, and participant observation.

Although there may be data from reports and books, I was able to portray the evolution of Korean food based on the stories I heard from countless people I met while researching.

This is also the methodology of cultural anthropology and folklore, which are my majors.

We proceeded by verifying and proving newspaper and statistical data based on their testimonies.

5.

This book assumes four spaces selling food menus.

What criteria and reasons were used to select noodle restaurants, large-scale restaurants, Joseon restaurants, and even new restaurants?

- The noodle restaurants, large-scale restaurants, and Joseon restaurants covered in Parts 2, 3, and 4 of this book can be seen as the three most popular types of restaurants in the 20th century, when industrialization and urbanization were in full swing.

Restaurants from these periods show a clear difference from food consumption during the Joseon Dynasty.

During the Joseon Dynasty, which was based on Neo-Confucianism, cities and commerce were neglected.

That is why, in the 19th century, during the colonial period and through war, we were rapidly incorporated into the paradigms of the world system, urbanization, and industrialization, and home cooking menus entered the restaurant industry.

The very first runner was a noodle restaurant.

The soup eaten at home and the soup served at a soup restaurant have become different concepts.

The second Joseon cuisine that was dealt with was a modified form of the cuisine or ryotei that was popular in Japan during the late Edo period. Gisaeng, who had existed since the pre-modern period, became deeply connected to the cuisine and became popular during the colonial period.

Daepotjip is a restaurant mainly used by people who moved from farmers to urban workers, who led Korean society after the Korean War.

You can also see that the dining spaces that were popular at each time period were different.

We've designed it so that you can understand the meaning of these restaurants while also being able to find and view the specific foods sold there, one by one, as if clicking on them.

The prologue, parts 1, and 5 of this book provide a more introductory overview of the overall flow.

Part 1 describes the flow of the 19th and early 20th centuries as if looking at a museum exhibition hall.

The prologue and part 1 are definitely worth reading, as they explain why these changes occurred.

Part 5 covers the story from the 1950s to the present.

What I wanted to say through this book is that what's important in the history of food is not its origins but when it became popular.

This book often introduces literature from books on food from the late Joseon Dynasty, and immediately compares how this food has changed in the 20th century.

In this way, we can see how one food was consumed differently in the 18th and 19th centuries, the first half of the 20th century, and the period after the 1960s.

It may be the same menu and recipe, but you can see the differences at a glance.

6.

Please tell us about your future research direction.

- Over the past two and a half years, I have received research funding and have been working on analysing over 1,500 historical documents, including food-related literature and old documents from the Joseon Dynasty.

More than 60 researchers were mobilized.

Previous food research was conducted by referencing the papers and research results of my predecessors, Professors Lee Seong-woo and Jang Ji-yeon, who organized and introduced literature at a time when it was difficult to find original sources.

However, previous research conducted without looking at the raw materials had many problems.

As I was reprocessing processed data, there were many cases where such content was not found when I actually looked for the original source.

Because of this, I felt it was necessary to reveal the raw material to the readers.

In “Korean History on the Table,” we also tried to reveal the original sources.

In the future, I would like to write a book about people who wrote about cooking and food in Korean history, and the impressions, feelings, and information they left about that food, although this may not be widely known to the general public or researchers.

The purpose is to understand the social conditions of the time through the life, books, and literature of the person who left records about food.

The goal is to make people understand that people actually consumed food in this way during the Goryeo Dynasty up to the 1940s.

If "Food Humanities" introduced my theoretical foundation, and "Korean History on the Table" presented the specific changes in menus during a specific period, the next book will introduce important food-related documents and literature from the entire history of the Korean Peninsula, which can be considered the original sources, by period, centered around the author.

Another project is to return to my original field of study and, through the methodologies of cultural anthropology and folklore, decipher how the three East Asian countries shared and differentiated their food during certain periods.

This work, based on 20 years of field research, examines the historical context of food across East Asia.

To give a simple example, the process of mixing Japanese soy sauce and Joseon soy sauce was covered in "Korean History on the Table," but this work will delve into this in more detail and closely show how the soy sauces of East Asia, which existed in a pre-modern style, were mixed and continued in parallel in different ways.

This book provided an opportunity to reflect on the social and cultural implications of the food we eat on a daily basis.

It seems like it would be an opportunity to reflect on the issues of food and living from a humanistic perspective by looking at the menus in the book, as if choosing food from a table.

I look forward to your future research.

Thank you for taking the time to interview me.

The first modern restaurant, the noodle house; the Joseon restaurant, a variation of the Japanese-style high-class restaurant; the Daepotjip, which filled the bellies of the common people with meals and snacks during the industrialization period; the main menus of the new restaurants born through globalization have been popular depending on the consumer base and the time period.

This book microscopically examines the origins and evolution of 34 food menus that have driven the modern restaurant industry, including seolleongtang, galbi, shinseonro, bindaetteok, and jajangmyeon, while simultaneously presenting new possibilities for "critical food studies" through macroscopic discourse analysis of political, economic, social, and cultural changes.

By following the sharp interpretations that penetrate the flow of time through interdisciplinary research that crosses the theories and methods of cultural anthropology, folklore, history, and sociology based on abundant historical materials such as newspapers, magazines, advertisements, and old documents, you can vividly restore the lives and cultural history of the people of the time, allowing you to encounter a new dimension of Korean history.

The task of examining the history of food is never easy.

Who can say with certainty that the cabbage we eat today is the same as the cabbage described in cookbooks from over a century ago? Could we recreate Joseon Dynasty cabbage kimchi, assuming the "cabbage" described in ancient texts is the same as today's cabbage? Even if we could recreate it similarly, would we be able to capture the thoughts of the people of that time in this dish? Simply listing the specifics of certain texts in a food history study is not history.

Only by uncovering why people at the time had no choice but to make and eat such food can we approach the history of that food.

The history of food is never a collection of episodes.

There is economics, politics, and society in it.

-From "Publishing a Book"

The history of food may seem trivial when approached from a macroscopic perspective.

But nothing encompasses both macro and micro history as much as the history of food.

Everyone, whether good or bad, must eat to live, and to eat, they engage in economic activities, social activities, and political activities.

So, if you know what an individual or a society ate and how they lived, you can see the history of that society.

In particular, the history of food experienced by the 'Korea' of the Korean Empire, which was incorporated into the 20th century world system, the colonial period, and the 'Korea' of the Republic of Korea is an exquisite combination of macrohistory and microhistory.

-From "Publishing a Book"

Interview with the Author

Hello, teacher.

In 2011, through “Food Humanities,” you continued the intersection of culinary studies and humanities, saying, “Food as a meal is part of everyday life, but food as culture and history is the humanities.” I am delighted to be able to meet you again after such a long time through a new book.

This book is titled “Korean History on the Table,” and I have a few questions about it.

1.

It is said that there is a common question that Koreans ask when they meet foreigners.

The question is whether you have ever tried kimchi or bulgogi. It seems that Koreans recognize that food is a cultural heritage that represents Korea.

But you said in this book that the origins of the modern Korean dining table can be found in the 20th century. Why did you focus on the history of 20th-century food?

- I think the reason Koreans tend to think of food itself as a cultural heritage is because after the 1988 Seoul Olympics, when foreign tourists began to flow in in earnest and took an interest in Korean food, Koreans also tried to give it meaning through their own identity as “Korean.”

In the process of strengthening Korean identity, academia and the media have tended to seek answers to the origins of Korean food in the Joseon Dynasty in order to give it a long history.

Food doesn't change as quickly as other aspects of food, clothing, and shelter, but even so, it is bound to continue to change within a cultural context.

Food, in particular, underwent rapid changes during the modern system introduced through the colonial period in the 20th century and the economic development and industrialization of the 1960s.

I thought that rather than emphasizing only traditional foods, we should acknowledge the changes in food throughout the 20th century.

Because only by acknowledging change can we understand our current state, and only by knowing this can we predict the future of Korean food.

By examining the changes in food throughout the 20th century, as well as the political and economic shifts contained within, we can consider the question of why we eat this food now.

2.

What is the concept of "hybridization" in Korean food that this book addresses, and what are the issues you wanted to suggest to Korean food culture?

- This book examines each menu to show that the food we eat today is not necessarily limited to old Korean food.

This problem awareness was also contained in the previous work, “Food Humanities,” but “Korean History on the Table” shows each food in more detail.

Korean food isn't just about old dishes.

Although there was movement of food ingredients during the Joseon Dynasty, since then, the movement of food ingredients to the periphery and around the world has become full-scale, so mixing is inevitable.

I believe that a more important question in Korean food culture than what “Korean food” is is what and how Koreans have been eating.

The food consumed in our society is a blend of diverse cultures. Can we single out only the traditional Korean foods and assign them the identity of "Korean food"? I believe the key is "hybridity."

Korean food is a combination of the continuation of old dishes and the intervention of new ones.

In other words, 20th-century Korean food is the result of a 'hybridization' of discourses on colonialism, traditionalism, nationalism, statism, the world system, and globalization.

In this context, we should examine foods that came from outside, foods that are old but have changed over the 20th century due to internal and external factors.

To do this, we need to look at Korean society and food culture from a humanistic perspective.

3.

In my previous work, “Food Humanities,” I presented “critical food studies,” and I see “Korean History on the Table” as a detailed work that addresses the issues raised in that book.

What is 'critical food studies', and how does reading Korean history through it differ from conventional food studies?

- Food science is the study of food, which is closest to us.

Because food consumption is such a personal thing, you might think it's just a matter of taste or voluntary choice.

It may seem difficult to connect today's food choices to grand political and economic discourses.

But think about when you buy groceries at the store, cook at home, or eat out.

Unless we are self-sufficient in all our food supplies, we will inevitably be in contact with national and global systems in the distribution of food ingredients.

The 20th century was a dynamic period of transition from pre-modern to modern times and integration into the global system, providing a prime example of how the small-scale food consumption of individuals transformed within the interconnectedness of vast nations and societies.

I can't say that everything is intertwined, but I wanted to reveal in this book the possibility that it is connected to the social and historical context.

In that sense, I wanted to organize the food produced and consumed by Koreans and the thoughts related to it, from small texts to grand discourses.

That is the task of reading Korean history through food.

Perhaps readers would find it easier to read if the food changes were organized chronologically, but from a food science perspective, I tried to show, through each menu, why people wanted to make and eat this food, why they went to restaurants, why the ingredients and food were sold, and finally, why the food became popular.

Through this, I wanted to provide an opportunity to look at Korea's 20th century through different eyes.

From this perspective, I propose ‘critical food studies.’

Critical food studies is a research perspective that goes beyond simply examining the origins of a food, its health benefits, or how it is made, and instead seeks to uncover the political, economic, social, and cultural implications that made its popularity possible.

The result of that specific research is this book.

4.

This book has a unique approach to reading ancient literature.

How did you primarily find and work with food literature?

- Existing food science researchers have only used cookbooks or references to dishes from the Joseon Dynasty as literature.

There are many cookbooks from the colonial period, but they were only used as reference and not considered traditional, so they were not given much weight.

I focused on cookbooks, magazines, and newspapers from the colonial period as sources for food studies.

These materials are digitized, making them easy to find and allowing you to explore a wide range of subjects.

However, the task of finding, filtering, and interpreting the numerous data about a single food takes as much effort as preparing a paper.

To explain food after liberation, I looked up statistical data from the time and read countless doctoral dissertations on food policy at the time currently being conducted in sociology and economics, which were very helpful.

Since the 1960s, the food data has been collected over 20 years through fieldwork, including interviews, local research, and participant observation.

Although there may be data from reports and books, I was able to portray the evolution of Korean food based on the stories I heard from countless people I met while researching.

This is also the methodology of cultural anthropology and folklore, which are my majors.

We proceeded by verifying and proving newspaper and statistical data based on their testimonies.

5.

This book assumes four spaces selling food menus.

What criteria and reasons were used to select noodle restaurants, large-scale restaurants, Joseon restaurants, and even new restaurants?

- The noodle restaurants, large-scale restaurants, and Joseon restaurants covered in Parts 2, 3, and 4 of this book can be seen as the three most popular types of restaurants in the 20th century, when industrialization and urbanization were in full swing.

Restaurants from these periods show a clear difference from food consumption during the Joseon Dynasty.

During the Joseon Dynasty, which was based on Neo-Confucianism, cities and commerce were neglected.

That is why, in the 19th century, during the colonial period and through war, we were rapidly incorporated into the paradigms of the world system, urbanization, and industrialization, and home cooking menus entered the restaurant industry.

The very first runner was a noodle restaurant.

The soup eaten at home and the soup served at a soup restaurant have become different concepts.

The second Joseon cuisine that was dealt with was a modified form of the cuisine or ryotei that was popular in Japan during the late Edo period. Gisaeng, who had existed since the pre-modern period, became deeply connected to the cuisine and became popular during the colonial period.

Daepotjip is a restaurant mainly used by people who moved from farmers to urban workers, who led Korean society after the Korean War.

You can also see that the dining spaces that were popular at each time period were different.

We've designed it so that you can understand the meaning of these restaurants while also being able to find and view the specific foods sold there, one by one, as if clicking on them.

The prologue, parts 1, and 5 of this book provide a more introductory overview of the overall flow.

Part 1 describes the flow of the 19th and early 20th centuries as if looking at a museum exhibition hall.

The prologue and part 1 are definitely worth reading, as they explain why these changes occurred.

Part 5 covers the story from the 1950s to the present.

What I wanted to say through this book is that what's important in the history of food is not its origins but when it became popular.

This book often introduces literature from books on food from the late Joseon Dynasty, and immediately compares how this food has changed in the 20th century.

In this way, we can see how one food was consumed differently in the 18th and 19th centuries, the first half of the 20th century, and the period after the 1960s.

It may be the same menu and recipe, but you can see the differences at a glance.

6.

Please tell us about your future research direction.

- Over the past two and a half years, I have received research funding and have been working on analysing over 1,500 historical documents, including food-related literature and old documents from the Joseon Dynasty.

More than 60 researchers were mobilized.

Previous food research was conducted by referencing the papers and research results of my predecessors, Professors Lee Seong-woo and Jang Ji-yeon, who organized and introduced literature at a time when it was difficult to find original sources.

However, previous research conducted without looking at the raw materials had many problems.

As I was reprocessing processed data, there were many cases where such content was not found when I actually looked for the original source.

Because of this, I felt it was necessary to reveal the raw material to the readers.

In “Korean History on the Table,” we also tried to reveal the original sources.

In the future, I would like to write a book about people who wrote about cooking and food in Korean history, and the impressions, feelings, and information they left about that food, although this may not be widely known to the general public or researchers.

The purpose is to understand the social conditions of the time through the life, books, and literature of the person who left records about food.

The goal is to make people understand that people actually consumed food in this way during the Goryeo Dynasty up to the 1940s.

If "Food Humanities" introduced my theoretical foundation, and "Korean History on the Table" presented the specific changes in menus during a specific period, the next book will introduce important food-related documents and literature from the entire history of the Korean Peninsula, which can be considered the original sources, by period, centered around the author.

Another project is to return to my original field of study and, through the methodologies of cultural anthropology and folklore, decipher how the three East Asian countries shared and differentiated their food during certain periods.

This work, based on 20 years of field research, examines the historical context of food across East Asia.

To give a simple example, the process of mixing Japanese soy sauce and Joseon soy sauce was covered in "Korean History on the Table," but this work will delve into this in more detail and closely show how the soy sauces of East Asia, which existed in a pre-modern style, were mixed and continued in parallel in different ways.

This book provided an opportunity to reflect on the social and cultural implications of the food we eat on a daily basis.

It seems like it would be an opportunity to reflect on the issues of food and living from a humanistic perspective by looking at the menus in the book, as if choosing food from a table.

I look forward to your future research.

Thank you for taking the time to interview me.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: September 2, 2013

- Page count, weight, size: 572 pages | 981g | 152*224*35mm

- ISBN13: 9788958626541

- ISBN10: 8958626542

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)