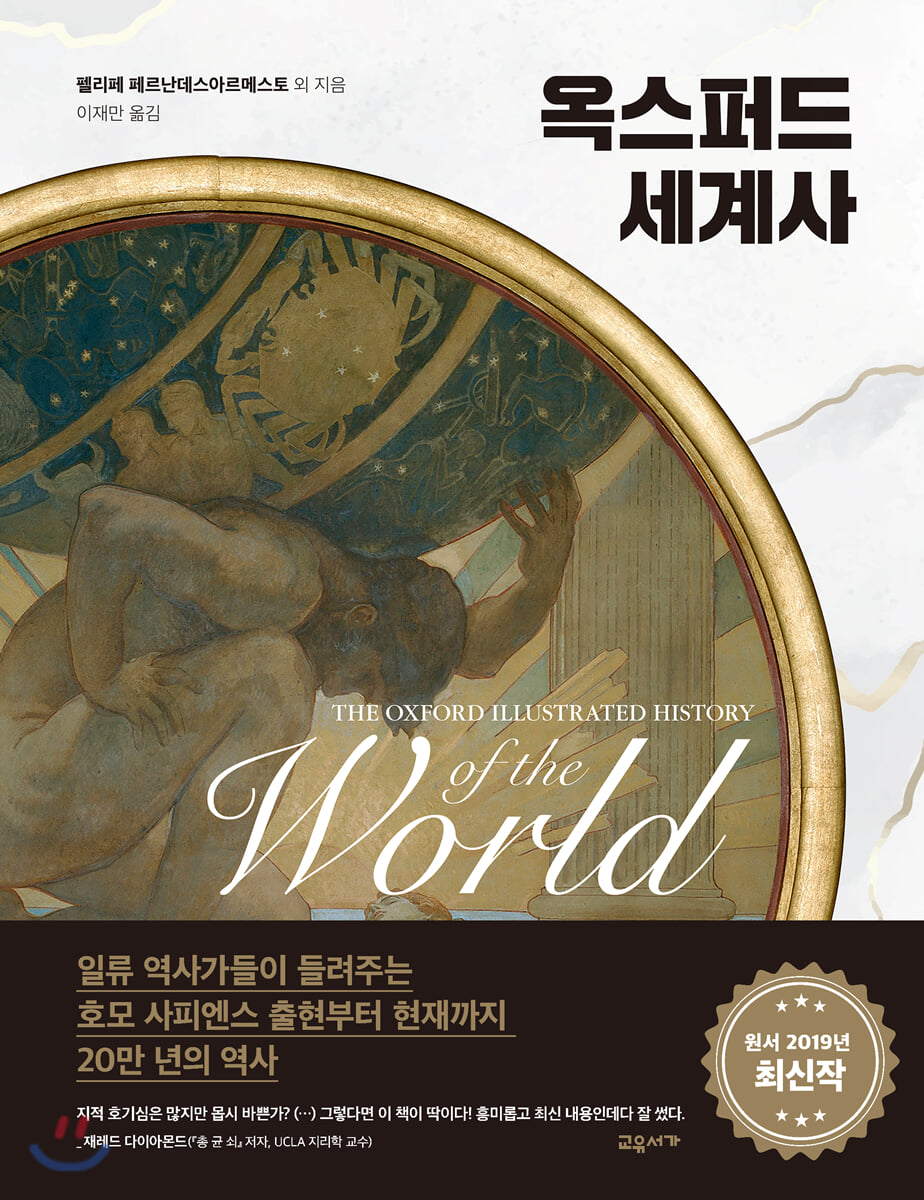

Oxford World History

|

Description

Book Introduction

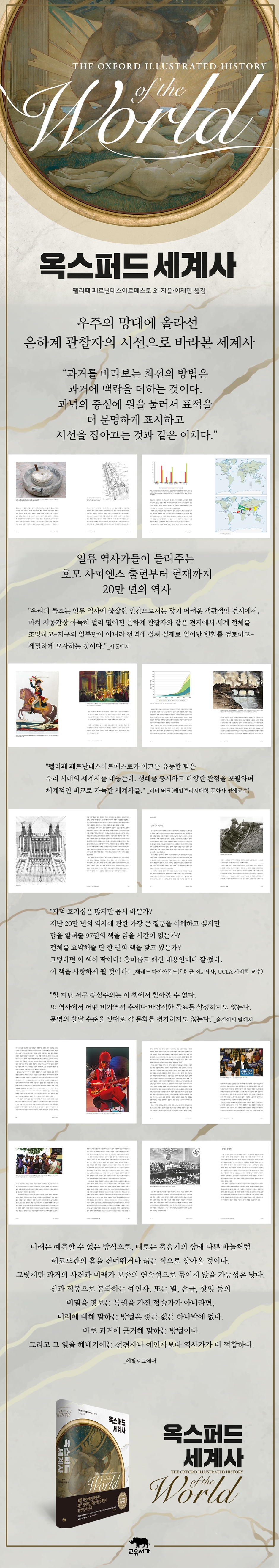

World history seen through the eyes of a galactic observer standing on a cosmic watchtower

View past and present, region and world simultaneously from multiple perspectives.

A 200,000-year history from the emergence of Homo sapiens to the present, told by the world's leading historians.

A fascinating and systematic narrative of divergence, convergence, and accelerating change that permeates humanity's diversity!

“The best way to look at the past is to give it context.

It's like putting a circle around the center of a target to make it more visible and grab people's attention."

Are you intellectually curious but incredibly busy? (…) Then this book is for you! It's engaging, up-to-date, and well-written.

Jared Diamond (author of Guns, Germs, and Steel, professor of geography at UCLA)

※ 150 maps, drawings, and photos, original book, latest edition from 2019!

What would history look like to a galactic observer perched on a cosmic watchtower? The latest world history book, "The Oxford History of the World," has been published (published by Kyoyuseo), telling the story of all the changes that have shaped our world, for better or worse, up to the present day in the 21st century.

This book covers the entire history of mankind.

World-class historians, including lead author Felipe Fernandez-Armesto, describe the history of Homo sapiens spanning 200,000 years from its emergence to the present day.

The authors explore the upheavals of the environment, the interplay of ideologies, the stages and exchanges of culture, political conflict and cooperation, the succession of nations and empires, the liberation of energy, ecology and economics, and the contacts, conflicts, and ripple effects that have helped shape the world we live in today.

While I admire and sometimes admire human achievements, I also view the fruits of human labor with skepticism, almost cynical views.

It is no coincidence that the former deals with the pre-modern period and the latter with the post-modern period.

It also focuses on the continuity between past and present, while also noting human innovation and transformation.

Some narratives focus on long-term trends and universals, while others examine short-term contingencies and particularities in detail.

This book vividly demonstrates the diversity of perspectives needed to view world history as a whole.

View past and present, region and world simultaneously from multiple perspectives.

A 200,000-year history from the emergence of Homo sapiens to the present, told by the world's leading historians.

A fascinating and systematic narrative of divergence, convergence, and accelerating change that permeates humanity's diversity!

“The best way to look at the past is to give it context.

It's like putting a circle around the center of a target to make it more visible and grab people's attention."

Are you intellectually curious but incredibly busy? (…) Then this book is for you! It's engaging, up-to-date, and well-written.

Jared Diamond (author of Guns, Germs, and Steel, professor of geography at UCLA)

※ 150 maps, drawings, and photos, original book, latest edition from 2019!

What would history look like to a galactic observer perched on a cosmic watchtower? The latest world history book, "The Oxford History of the World," has been published (published by Kyoyuseo), telling the story of all the changes that have shaped our world, for better or worse, up to the present day in the 21st century.

This book covers the entire history of mankind.

World-class historians, including lead author Felipe Fernandez-Armesto, describe the history of Homo sapiens spanning 200,000 years from its emergence to the present day.

The authors explore the upheavals of the environment, the interplay of ideologies, the stages and exchanges of culture, political conflict and cooperation, the succession of nations and empires, the liberation of energy, ecology and economics, and the contacts, conflicts, and ripple effects that have helped shape the world we live in today.

While I admire and sometimes admire human achievements, I also view the fruits of human labor with skepticism, almost cynical views.

It is no coincidence that the former deals with the pre-modern period and the latter with the post-modern period.

It also focuses on the continuity between past and present, while also noting human innovation and transformation.

Some narratives focus on long-term trends and universals, while others examine short-term contingencies and particularities in detail.

This book vividly demonstrates the diversity of perspectives needed to view world history as a whole.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

introduction

Part 1: Children of the Glacier

The beginning of human global expansion and cultural divergence

- From about 200,000 years ago to 12,000 years ago

Chapter 1: The Emergence of Humanity in the Ice Age: The Emergence and Spread of an Adaptive Species

_Clive Gamble

Chapter 2: The Mind in the Ice: Art and Thought Before Agriculture

_Felipe Fernandez Armesto

Part 2: With Clay and Metal

Cultures from the advent of agriculture to the Bronze Age crisis

―From around 10,000 BC to around 1000 BC

Chapter 3: A Warming World

_Martin Jones

Chapter 4: Peasant Empires: The Climax and Crisis of the Agrarian State and the Agrarian City

_Felipe Fernandez Armesto

Part 3: The Tremors of Empires

From the 'Dark Ages' of the early 1st millennium BC to the mid-14th century AD

Chapter 5: Material Life: From the Bronze Age Crisis to the Black Death

_John Brooke

Chapter 6: Intellectual Traditions: Philosophy, Science, Religion, and Art—500 BCE–AD 1350

_David Northrup

Chapter 7: Growth: Social and Political Organization—1000 BC–AD 1350

_Ian Morris

Part 4: Climate Reversal

Diffusion and Innovation in the Face of Pandemic and Cold

―From the mid-14th century to the early 19th century

Chapter 8: A Converging World: Economic and Ecological Encounters—1350–1815

_David Northrup

Chapter 9: Renaissance, Reformation, and Mental Revolution: Intellect and Art in the Early Modern World

_Manuel Lucena Giraldo

Chapter 10: Connecting Through Emotion and Experience: Monarchs, Merchants, Mercenaries, and Immigrants in the Early Modern World

Anjana Singh

Part 5: Great Acceleration

Accelerating Change in a Warming World

―From around 1815 to around 2008

Chapter 11: The Anthropocene: The Background of Two Transformative Centuries

_David Christian

Chapter 12: The Modern World and Its Demons: Ideology in Art, Science, and Thought and Beyond—1815–2008

_Paolo Luca Bernardini

Chapter 13: Politics and Society in Fluid Change: Relationships, Institutions, and Conflicts: From the Beginning of Western Hegemony to the Beginning of American Hegemony

_Jeremy Black

Epilogue

Reading Guide/Translator's Note/Illustration Sources/Index

Part 1: Children of the Glacier

The beginning of human global expansion and cultural divergence

- From about 200,000 years ago to 12,000 years ago

Chapter 1: The Emergence of Humanity in the Ice Age: The Emergence and Spread of an Adaptive Species

_Clive Gamble

Chapter 2: The Mind in the Ice: Art and Thought Before Agriculture

_Felipe Fernandez Armesto

Part 2: With Clay and Metal

Cultures from the advent of agriculture to the Bronze Age crisis

―From around 10,000 BC to around 1000 BC

Chapter 3: A Warming World

_Martin Jones

Chapter 4: Peasant Empires: The Climax and Crisis of the Agrarian State and the Agrarian City

_Felipe Fernandez Armesto

Part 3: The Tremors of Empires

From the 'Dark Ages' of the early 1st millennium BC to the mid-14th century AD

Chapter 5: Material Life: From the Bronze Age Crisis to the Black Death

_John Brooke

Chapter 6: Intellectual Traditions: Philosophy, Science, Religion, and Art—500 BCE–AD 1350

_David Northrup

Chapter 7: Growth: Social and Political Organization—1000 BC–AD 1350

_Ian Morris

Part 4: Climate Reversal

Diffusion and Innovation in the Face of Pandemic and Cold

―From the mid-14th century to the early 19th century

Chapter 8: A Converging World: Economic and Ecological Encounters—1350–1815

_David Northrup

Chapter 9: Renaissance, Reformation, and Mental Revolution: Intellect and Art in the Early Modern World

_Manuel Lucena Giraldo

Chapter 10: Connecting Through Emotion and Experience: Monarchs, Merchants, Mercenaries, and Immigrants in the Early Modern World

Anjana Singh

Part 5: Great Acceleration

Accelerating Change in a Warming World

―From around 1815 to around 2008

Chapter 11: The Anthropocene: The Background of Two Transformative Centuries

_David Christian

Chapter 12: The Modern World and Its Demons: Ideology in Art, Science, and Thought and Beyond—1815–2008

_Paolo Luca Bernardini

Chapter 13: Politics and Society in Fluid Change: Relationships, Institutions, and Conflicts: From the Beginning of Western Hegemony to the Beginning of American Hegemony

_Jeremy Black

Epilogue

Reading Guide/Translator's Note/Illustration Sources/Index

Detailed image

Into the book

The challenge faced when settling north of 55 degrees north latitude was not necessarily the cold.

Of course, it was bitterly cold, but the bigger problem was that the characteristics of human settlement were diluted.

In particular, the exchange of goods through extensive regional networks and customs such as kinship were diluted.

In environments with low population densities and no food storage, it would have been difficult for human groups to function as social units through predictable contact and association.

--- p.63

Traces of similar stencil techniques can be found in some European cave paintings.

Europe appears to be rich in artifacts, but this may be a trick of the evidence.

In other words, it may be the result of exceptionally consistent and meticulous excavation of a corner of a global phenomenon.

(…) There are also valid arguments supporting the claim that cave paintings should be viewed as hunters' memory techniques.

The shape of the hooves of animals, their seasonal habits, their favorite foods, and their footprints were important items in the artists' repertoire of images.

--- p.82

A careful examination of the caves reveals that an intellectual class emerged alongside the military class.

By selecting elites with the ability to communicate with the spirit, Ice Age societies were able to bring about what might be called the first political revolutions, freeing the physically strong from the oppression of those born into privilege.

Shamanism replaced the strong with prophets and wise men.

--- p.101

In each of these new ecosystems, there were familiar bean pods not too far away, and even if more familiar forms were unavailable, less familiar ones could be tried.

This might best be described as a 'risk tolerable' strategy rather than a low-risk one, and some degree of indigestion and the occasional risk of more severe diarrhea would have been a consistent feature of the soy experiments.

--- p.117

Such a minority might have traveled vast distances, or even crossed continents, before returning to their home base.

(…) In prehistoric times, such small groups would have been much smaller and the journey would have taken months, perhaps even years, but it was still possible to cross the continent.

(…) The more secure the home base, the more ambitious the journeys could be.

--- p.153

The Code of Hammurabi replaced the physical presence and verbal statements of the ruler.

“Whoever has been unjustly oppressed, come before my statue, the King of Justice, read my epitaph carefully and listen to my precious words.

“My stone will make his case clear.” This was not a law as we know it, a law inherited from ancient times or enacted to limit the power of rulers.

Rather, it was a means of perpetuating the king's command.

--- p.179

Although the major river basins are similar to each other, they help us identify at least two reasons for cultural divergence during that time.

First, emission was influenced by the environment.

The larger or more diverse the resource base, the larger and longer lasting the society could be.

The diversity of the environment allowed people in the river basin to enjoy more resources than those in less affluent areas.

(…) Second, the interaction between societies, in which they learn from each other, compete with each other, and exchange cultures, was important.

Egypt maintained contact with Mesopotamia, and Mesopotamia maintained contact with Harappa.

China's relative isolation (similar to the extreme isolation of many New World civilizations) may have contributed to its late initiation into some of the processes of change that all major riverine societies experienced.

--- p.190∼191

Evidence from the Old World suggests that conditions were harsh for hundreds of years during this crisis, and that epidemics undoubtedly accompanied the Bronze Age crisis.

Records exist from the Hittites in the 14th century BC, the Trojan War in the 12th century BC, and the Twelve Tribes of Israel.

The plague, once thought to have originated only in the late Middle Ages, appears to have originated much earlier.

The earliest genetic evidence comes from a mass grave in the Altai region of Central Asia, dating to around 2800 BC, showing that plague was endemic to the steppes throughout the Bronze Age and was closely associated with the Indo-European nomads who migrated westward into Europe.

--- p.215

What gave birth to the significant thinkers of this era? Some scholars have argued that although the intellectual traditions of this era originated in different regions, they shared similar philosophical principles and religious insights.

Other scholars have argued that literacy, empires, and coinage were also spreading during the period when great sages emerged.

(…) While the exceptional individuals of the Axial Age deserve recognition for their intellectual and spiritual insights, the key reason their teachings have endured is that they were written down.

--- p.260

Christianity, Islam, and Buddhism have all adapted their religious concepts and practices to the cultures of prospective converts as part of a long-term strategy to harmonize their core values with local cultures.

--- p.281

Growth required two conditions.

First, it required the exceptionally productive brains of Homo sapiens, which evolved about 100,000 years ago, and second, the warm, humid climate that has prevailed since the end of the Ice Age (what archaeologist Brian Fagan calls the “long summer”).

There were several long summers before 100,000 BC, but no Homo sapiens were able to respond to them by forming larger structures.

And between 100,000 and 15,000 BC, Homo sapiens were around, but there were no long summers.

Only in the past 15,000 years have both conditions been present, allowing Homo sapiens, the "knowing human," to become Homo superans, the "growing human."

--- p.317

The reasons why the Sui dynasty succeeded and Justinian, Charlemagne, and Alma-Mun failed are still debated, but the consequences of the dynasty's success are clear.

This means that the center of gravity of the world organization has shifted from western to eastern Eurasia.

Around 700 AD, one million people lived in Chang'an and another 500,000 in Luoyang.

The Sui Dynasty dug the Grand Canal to transport rice from the Yangtze River basin in the south, where rice paddies were expanding, to the prosperous cities in the north.

--- p.349

Traditionally, historians have focused on Europe's role in pioneering transoceanic trade, which directly linked Asia to markets in Europe and the Americas.

However, during this period, intra-Asian trade greatly exceeded intercontinental trade in both volume and value.

Europeans primarily sought opportunities to profit from price patterns within Asia.

For example, the prices of silver and copper were relatively cheap in Japan and more expensive in China, while the price of gold was high in India.

--- p.374∼375

The oldest form of globalization is cultural globalization.

Cultural globalization has made all other forms (economic, technological, scientific, and ecological globalization) possible.

If we wish to transcend the constraints of the world history narrative favored in the past—that is, the narrative as a process of projecting Europe onto the rest of the world (a providential, linear, progressive narrative), we need to keep this in mind.

Such narratives portray events from the 14th to the 19th centuries as if they were evolutionary episodes in which a superior civilization, fit to survive, achieved a teleological victory over the barbarians, or a chosen 'humanity' (or a part of humanity) over the barbarians.

However, the "centers" that people at the time defined as civilization were scattered all over the world, just like the "peripheries" that they considered inferior places to conquer or exploit.

--- p.406

Captain Cook's desire to be "the first man to see" before he was stabbed to death on a Hawaiian beach in 1779 was inseparable from the sense of mystery that has permeated travel literature since time immemorial, turning the reader's gaze elsewhere to a surprising event.

The truthfulness of explorers is always questionable.

Yet, even though we suspect their texts may be deceptive, we still read travel literature as if it were a lens powerful enough to correct all distortions.

--- p.441

The relationship between the Enlightenment and the French Revolution is complex.

The two terms encompass a set of features and events that are awkwardly compatible with each other.

It is a hasty assumption that the Enlightenment led to the French Revolution.

In the case of the Enlightenment, on one hand, there was a deistic and naturalistic Enlightenment with a distinct secular character.

--- p.444

From Europe to the Ming and Qing dynasties, a common thread connected the empires of the early modern period.

All of these empires experienced what historians call a military revolution, a revolution triggered by the introduction of light, easy-to-handle firearms.

The need to train men in the use of these firearms led to the development of a system for maintaining armies.

This was a major difference from the medieval Turkic and Mongol empires, which disbanded their armies after completing conquests.

Standing armies gave monarchs more power.

The army repelled external enemies and suppressed internal rebellions.

Maintaining an army required a constant supply of money, the creation of new organizational structures, and the bureaucracy of administrative apparatus.

An expanded bureaucracy aided by the use of documents was also a common feature of early modern empires.

--- p.474

Just as the oppressed Native Americans endured the trauma of conquest and maintained the continuity of their traditional civilization, African slaves did not give up control of their lives.

They invented a new way of life on the plantation.

For example, under the shadow of their masters, they created new self-help groups, new religions (often combining fragments of Christianity with memories of African gods), new music (composed on the spot on instruments), and new languages (often adapted from the European masters' languages so that slaves from different regions could communicate with each other).

--- p.487

Even when looking at the entire history of mankind, and even the 4 billion years of Earth's history, the changes that have occurred in the past 200 years have been explosive and revolutionary.

What caused this change?

--- p.511

In 2005, more than 3 billion people (more than the entire world population in 1900) lived on less than $2.50 a day.

Although the total amount of wealth has increased, its distribution is more unequal than ever before.

In 2014, the richest 10 percent of the world's population controlled 87 percent of the world's wealth, while the bottom 50 percent controlled just 1 percent.

(…) Today, once a new disease emerges, it can spread through travel at a frightening rate, and bacteria and viruses can move, mix, and evolve at a rate that modern medicine cannot keep up with.

--- p.543

From a political perspective, the 'public' has become cohesive, but from a spiritual perspective, the 'public' has changed from a 'flock' to a 'public'.

No, to be more precise, it has become secularized.

--- p.555

The masses, the modern state, science and technology could all emerge in places where there was no 'art and literature'.

However, the presence or absence of God is a central element in all spiritual, intellectual, and artistic productions.

Art has constantly depicted the conflict between mutability and eternity, speaking of the human world and the eternal God, and through such depictions has justified artistic practice and expressed its deepest meaning.

A worldview that emphasizes the conditions of mutability and the fundamental role of sacred places thus champions the sacred dimension of art.

Such a worldview suggests that humans receive 'divine inspiration' when they respond to the mystery of existence.

For this reason, the so-called 'conversion to atheism' after 1789 had a tremendous impact on all intellectual, artistic and spiritual life of mankind.

--- p.564∼565

Through a complex process involving multiple acculturation strategies, nations maximized literacy rates, introduced compulsory education, established canons of literature and art, and transformed peasants and proletarians into substitutes for citizens, soldiers, and bourgeoisie.

I believe that the establishment of a 'truce' was a characteristic of modern times and one of the most detrimental factors to culture in general.

In my view, the canon, the product of state-sponsored intellectuals, has excluded the true masterpieces of world literature, art, and thought, thereby making the learning process dull.

I believe that modern intellectuals often change their character to fit into the canon, rather than maintaining artistic integrity, and even seek prestigious awards more than mass sales.

A classic example is the Nobel Prize, which includes the works of relevant authors in the canon while rejecting those who might disrupt the mainstream.

--- p.571∼572

As Umberto Eco once said, 'apocalyptic' figures actually turn out to be the type most attuned to the system.

Not only did they make a lot of money, but they also effectively proved the legitimacy of the system by seemingly challenging it.

--- p.576

Political, social, and economic advice from a charismatic person fails to capture the attention of the center, not because of the content, but because of the system that relentlessly polices such advice so that it reaches only a peripheral audience.

--- p.579

Religion, despotic power, class disparities, and human and social inequalities seemed to have disappeared with the French Revolution, along with the legal incapacity of the nobility, slaves, and women and minorities.

Those who sought to restore the 'old order' in 1815 were portrayed as 'ghosts' trying to rise from their eternal graves.

But those ghosts never truly rest, and tyrants and dogmatists still haunt the modern world, eager to stamp out progress through compromise or violence and extinguish the glimmer of Enlightenment that remains.

Of course, it was bitterly cold, but the bigger problem was that the characteristics of human settlement were diluted.

In particular, the exchange of goods through extensive regional networks and customs such as kinship were diluted.

In environments with low population densities and no food storage, it would have been difficult for human groups to function as social units through predictable contact and association.

--- p.63

Traces of similar stencil techniques can be found in some European cave paintings.

Europe appears to be rich in artifacts, but this may be a trick of the evidence.

In other words, it may be the result of exceptionally consistent and meticulous excavation of a corner of a global phenomenon.

(…) There are also valid arguments supporting the claim that cave paintings should be viewed as hunters' memory techniques.

The shape of the hooves of animals, their seasonal habits, their favorite foods, and their footprints were important items in the artists' repertoire of images.

--- p.82

A careful examination of the caves reveals that an intellectual class emerged alongside the military class.

By selecting elites with the ability to communicate with the spirit, Ice Age societies were able to bring about what might be called the first political revolutions, freeing the physically strong from the oppression of those born into privilege.

Shamanism replaced the strong with prophets and wise men.

--- p.101

In each of these new ecosystems, there were familiar bean pods not too far away, and even if more familiar forms were unavailable, less familiar ones could be tried.

This might best be described as a 'risk tolerable' strategy rather than a low-risk one, and some degree of indigestion and the occasional risk of more severe diarrhea would have been a consistent feature of the soy experiments.

--- p.117

Such a minority might have traveled vast distances, or even crossed continents, before returning to their home base.

(…) In prehistoric times, such small groups would have been much smaller and the journey would have taken months, perhaps even years, but it was still possible to cross the continent.

(…) The more secure the home base, the more ambitious the journeys could be.

--- p.153

The Code of Hammurabi replaced the physical presence and verbal statements of the ruler.

“Whoever has been unjustly oppressed, come before my statue, the King of Justice, read my epitaph carefully and listen to my precious words.

“My stone will make his case clear.” This was not a law as we know it, a law inherited from ancient times or enacted to limit the power of rulers.

Rather, it was a means of perpetuating the king's command.

--- p.179

Although the major river basins are similar to each other, they help us identify at least two reasons for cultural divergence during that time.

First, emission was influenced by the environment.

The larger or more diverse the resource base, the larger and longer lasting the society could be.

The diversity of the environment allowed people in the river basin to enjoy more resources than those in less affluent areas.

(…) Second, the interaction between societies, in which they learn from each other, compete with each other, and exchange cultures, was important.

Egypt maintained contact with Mesopotamia, and Mesopotamia maintained contact with Harappa.

China's relative isolation (similar to the extreme isolation of many New World civilizations) may have contributed to its late initiation into some of the processes of change that all major riverine societies experienced.

--- p.190∼191

Evidence from the Old World suggests that conditions were harsh for hundreds of years during this crisis, and that epidemics undoubtedly accompanied the Bronze Age crisis.

Records exist from the Hittites in the 14th century BC, the Trojan War in the 12th century BC, and the Twelve Tribes of Israel.

The plague, once thought to have originated only in the late Middle Ages, appears to have originated much earlier.

The earliest genetic evidence comes from a mass grave in the Altai region of Central Asia, dating to around 2800 BC, showing that plague was endemic to the steppes throughout the Bronze Age and was closely associated with the Indo-European nomads who migrated westward into Europe.

--- p.215

What gave birth to the significant thinkers of this era? Some scholars have argued that although the intellectual traditions of this era originated in different regions, they shared similar philosophical principles and religious insights.

Other scholars have argued that literacy, empires, and coinage were also spreading during the period when great sages emerged.

(…) While the exceptional individuals of the Axial Age deserve recognition for their intellectual and spiritual insights, the key reason their teachings have endured is that they were written down.

--- p.260

Christianity, Islam, and Buddhism have all adapted their religious concepts and practices to the cultures of prospective converts as part of a long-term strategy to harmonize their core values with local cultures.

--- p.281

Growth required two conditions.

First, it required the exceptionally productive brains of Homo sapiens, which evolved about 100,000 years ago, and second, the warm, humid climate that has prevailed since the end of the Ice Age (what archaeologist Brian Fagan calls the “long summer”).

There were several long summers before 100,000 BC, but no Homo sapiens were able to respond to them by forming larger structures.

And between 100,000 and 15,000 BC, Homo sapiens were around, but there were no long summers.

Only in the past 15,000 years have both conditions been present, allowing Homo sapiens, the "knowing human," to become Homo superans, the "growing human."

--- p.317

The reasons why the Sui dynasty succeeded and Justinian, Charlemagne, and Alma-Mun failed are still debated, but the consequences of the dynasty's success are clear.

This means that the center of gravity of the world organization has shifted from western to eastern Eurasia.

Around 700 AD, one million people lived in Chang'an and another 500,000 in Luoyang.

The Sui Dynasty dug the Grand Canal to transport rice from the Yangtze River basin in the south, where rice paddies were expanding, to the prosperous cities in the north.

--- p.349

Traditionally, historians have focused on Europe's role in pioneering transoceanic trade, which directly linked Asia to markets in Europe and the Americas.

However, during this period, intra-Asian trade greatly exceeded intercontinental trade in both volume and value.

Europeans primarily sought opportunities to profit from price patterns within Asia.

For example, the prices of silver and copper were relatively cheap in Japan and more expensive in China, while the price of gold was high in India.

--- p.374∼375

The oldest form of globalization is cultural globalization.

Cultural globalization has made all other forms (economic, technological, scientific, and ecological globalization) possible.

If we wish to transcend the constraints of the world history narrative favored in the past—that is, the narrative as a process of projecting Europe onto the rest of the world (a providential, linear, progressive narrative), we need to keep this in mind.

Such narratives portray events from the 14th to the 19th centuries as if they were evolutionary episodes in which a superior civilization, fit to survive, achieved a teleological victory over the barbarians, or a chosen 'humanity' (or a part of humanity) over the barbarians.

However, the "centers" that people at the time defined as civilization were scattered all over the world, just like the "peripheries" that they considered inferior places to conquer or exploit.

--- p.406

Captain Cook's desire to be "the first man to see" before he was stabbed to death on a Hawaiian beach in 1779 was inseparable from the sense of mystery that has permeated travel literature since time immemorial, turning the reader's gaze elsewhere to a surprising event.

The truthfulness of explorers is always questionable.

Yet, even though we suspect their texts may be deceptive, we still read travel literature as if it were a lens powerful enough to correct all distortions.

--- p.441

The relationship between the Enlightenment and the French Revolution is complex.

The two terms encompass a set of features and events that are awkwardly compatible with each other.

It is a hasty assumption that the Enlightenment led to the French Revolution.

In the case of the Enlightenment, on one hand, there was a deistic and naturalistic Enlightenment with a distinct secular character.

--- p.444

From Europe to the Ming and Qing dynasties, a common thread connected the empires of the early modern period.

All of these empires experienced what historians call a military revolution, a revolution triggered by the introduction of light, easy-to-handle firearms.

The need to train men in the use of these firearms led to the development of a system for maintaining armies.

This was a major difference from the medieval Turkic and Mongol empires, which disbanded their armies after completing conquests.

Standing armies gave monarchs more power.

The army repelled external enemies and suppressed internal rebellions.

Maintaining an army required a constant supply of money, the creation of new organizational structures, and the bureaucracy of administrative apparatus.

An expanded bureaucracy aided by the use of documents was also a common feature of early modern empires.

--- p.474

Just as the oppressed Native Americans endured the trauma of conquest and maintained the continuity of their traditional civilization, African slaves did not give up control of their lives.

They invented a new way of life on the plantation.

For example, under the shadow of their masters, they created new self-help groups, new religions (often combining fragments of Christianity with memories of African gods), new music (composed on the spot on instruments), and new languages (often adapted from the European masters' languages so that slaves from different regions could communicate with each other).

--- p.487

Even when looking at the entire history of mankind, and even the 4 billion years of Earth's history, the changes that have occurred in the past 200 years have been explosive and revolutionary.

What caused this change?

--- p.511

In 2005, more than 3 billion people (more than the entire world population in 1900) lived on less than $2.50 a day.

Although the total amount of wealth has increased, its distribution is more unequal than ever before.

In 2014, the richest 10 percent of the world's population controlled 87 percent of the world's wealth, while the bottom 50 percent controlled just 1 percent.

(…) Today, once a new disease emerges, it can spread through travel at a frightening rate, and bacteria and viruses can move, mix, and evolve at a rate that modern medicine cannot keep up with.

--- p.543

From a political perspective, the 'public' has become cohesive, but from a spiritual perspective, the 'public' has changed from a 'flock' to a 'public'.

No, to be more precise, it has become secularized.

--- p.555

The masses, the modern state, science and technology could all emerge in places where there was no 'art and literature'.

However, the presence or absence of God is a central element in all spiritual, intellectual, and artistic productions.

Art has constantly depicted the conflict between mutability and eternity, speaking of the human world and the eternal God, and through such depictions has justified artistic practice and expressed its deepest meaning.

A worldview that emphasizes the conditions of mutability and the fundamental role of sacred places thus champions the sacred dimension of art.

Such a worldview suggests that humans receive 'divine inspiration' when they respond to the mystery of existence.

For this reason, the so-called 'conversion to atheism' after 1789 had a tremendous impact on all intellectual, artistic and spiritual life of mankind.

--- p.564∼565

Through a complex process involving multiple acculturation strategies, nations maximized literacy rates, introduced compulsory education, established canons of literature and art, and transformed peasants and proletarians into substitutes for citizens, soldiers, and bourgeoisie.

I believe that the establishment of a 'truce' was a characteristic of modern times and one of the most detrimental factors to culture in general.

In my view, the canon, the product of state-sponsored intellectuals, has excluded the true masterpieces of world literature, art, and thought, thereby making the learning process dull.

I believe that modern intellectuals often change their character to fit into the canon, rather than maintaining artistic integrity, and even seek prestigious awards more than mass sales.

A classic example is the Nobel Prize, which includes the works of relevant authors in the canon while rejecting those who might disrupt the mainstream.

--- p.571∼572

As Umberto Eco once said, 'apocalyptic' figures actually turn out to be the type most attuned to the system.

Not only did they make a lot of money, but they also effectively proved the legitimacy of the system by seemingly challenging it.

--- p.576

Political, social, and economic advice from a charismatic person fails to capture the attention of the center, not because of the content, but because of the system that relentlessly polices such advice so that it reaches only a peripheral audience.

--- p.579

Religion, despotic power, class disparities, and human and social inequalities seemed to have disappeared with the French Revolution, along with the legal incapacity of the nobility, slaves, and women and minorities.

Those who sought to restore the 'old order' in 1815 were portrayed as 'ghosts' trying to rise from their eternal graves.

But those ghosts never truly rest, and tyrants and dogmatists still haunt the modern world, eager to stamp out progress through compromise or violence and extinguish the glimmer of Enlightenment that remains.

--- p.588∼589

Publisher's Review

The Oxford University History Series' World History Edition, a cutting-edge world history book reflecting a new perspective on history.

This book is the world history edition of 'The Oxford Illustrated History' series published by Oxford University Press in England.

Beginning with the emergence of humanity, this book reflects not only the achievements of past research but also changes in perspectives on history.

In the past, the main content of history was human activity, especially that of civilized people, but now its scope has expanded to include not only pre-civilized humans, but also non-human factors such as the universe, the Earth, the environment, climate, life forms, and diseases.

In fact, books in the so-called "big history" field (David Christian, one of the authors of this book, is a pioneer in this field) usually begin with the birth of the universe.

In short, almost all changes in the past that are now known and can be inferred have become subjects worthy of description under the name of history.

This book, which reflects this shift in historical perspective, differs from conventional world history books that describe the origins of ancient civilizations by focusing on the early days of humanity, that is, the period when Sapiens emerged and evolved in the hominin world.

The geographical scope is literally the entire world.

The authors describe all regions of the world where humans have lived in the context of divergence, convergence, and change.

There is no trace of outdated Western-centrism.

Nor does it assume any irreversible trends or desirable goals in history.

We don't even evaluate each culture by the level of development of civilization.

In short, this book is a compilation of the latest achievements in historical research.

Important Long-Term Trends to Keep in Mind in the COVID-19 Era

This book reveals two important long-term trends that we, living in the "COVID-19 era," should keep in mind as we look back on human history and look ahead.

One is that mankind has been bound to nature from the beginning.

As this book reveals, fluctuations in the Earth's climate system, such as solar minimums, monsoons, and El Niño, have influenced the rise and fall of civilizations.

A warm climate and adequate rainfall were the background for flourishing civilizations, while a cold climate and heavy rainfall or drought were the background for declining civilizations.

Since the Industrial Revolution, in the Anthropocene, humans have seemingly escaped the shackles of nature. However, recent unprecedented natural disasters and climate crises have shown us that humans are arrogantly testing the limits of nature, thus inviting catastrophe.

Another long-term trend is the power of epidemics, which have occasionally erupted and wreaked havoc on civilization and society.

As the authors document in considerable detail, epidemics such as the plague, smallpox, hemorrhagic fever, and influenza had a devastating impact on populations, paralyzed economies, and altered the geopolitical landscape.

This book is the world history edition of 'The Oxford Illustrated History' series published by Oxford University Press in England.

Beginning with the emergence of humanity, this book reflects not only the achievements of past research but also changes in perspectives on history.

In the past, the main content of history was human activity, especially that of civilized people, but now its scope has expanded to include not only pre-civilized humans, but also non-human factors such as the universe, the Earth, the environment, climate, life forms, and diseases.

In fact, books in the so-called "big history" field (David Christian, one of the authors of this book, is a pioneer in this field) usually begin with the birth of the universe.

In short, almost all changes in the past that are now known and can be inferred have become subjects worthy of description under the name of history.

This book, which reflects this shift in historical perspective, differs from conventional world history books that describe the origins of ancient civilizations by focusing on the early days of humanity, that is, the period when Sapiens emerged and evolved in the hominin world.

The geographical scope is literally the entire world.

The authors describe all regions of the world where humans have lived in the context of divergence, convergence, and change.

There is no trace of outdated Western-centrism.

Nor does it assume any irreversible trends or desirable goals in history.

We don't even evaluate each culture by the level of development of civilization.

In short, this book is a compilation of the latest achievements in historical research.

Important Long-Term Trends to Keep in Mind in the COVID-19 Era

This book reveals two important long-term trends that we, living in the "COVID-19 era," should keep in mind as we look back on human history and look ahead.

One is that mankind has been bound to nature from the beginning.

As this book reveals, fluctuations in the Earth's climate system, such as solar minimums, monsoons, and El Niño, have influenced the rise and fall of civilizations.

A warm climate and adequate rainfall were the background for flourishing civilizations, while a cold climate and heavy rainfall or drought were the background for declining civilizations.

Since the Industrial Revolution, in the Anthropocene, humans have seemingly escaped the shackles of nature. However, recent unprecedented natural disasters and climate crises have shown us that humans are arrogantly testing the limits of nature, thus inviting catastrophe.

Another long-term trend is the power of epidemics, which have occasionally erupted and wreaked havoc on civilization and society.

As the authors document in considerable detail, epidemics such as the plague, smallpox, hemorrhagic fever, and influenza had a devastating impact on populations, paralyzed economies, and altered the geopolitical landscape.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Publication date: December 21, 2020

- Format: Hardcover book binding method guide

- Page count, weight, size: 684 pages | 1,448g | 173*225*35mm

- ISBN13: 9791190277990

- ISBN10: 1190277999

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)