Everything was eternal, until it was gone.

|

Description

Book Introduction

- A word from MD

-

The Last Soviet StoryAfter the collapse of the Soviet Union, the prevailing view was that it was only a matter of time before the system would collapse.

Did those who actually lived within the system think this way? This book analyzes the experiences of Soviet members and documents the realities of socialist life.

October 22, 2019. History PD Son Min-gyu

“I never once thought that anything could change in the Soviet Union.

“I had the complete impression that everything would last forever.”

In 2005, Alexei Yurchak's Everything Was Forever, Until It Was Gone was published in the United States, causing a stir in academic circles and sparking a boom in cultural studies of the late Soviet era.

As the title implies, the collapse of the Soviet system was “unforeseeable and unimaginable until it happened, but once it did begin, it was experienced as a perfectly logical and exciting event.”

“I realized that people had always been preparing for the collapse of the system without even realizing it, and that life under socialism was formed by interesting paradoxes.” This book aims to question conventional assumptions about the way people who lived under Soviet socialism related to reality and to elucidate this paradox that lies at the very heart of the Soviet system.

By showing the realities of socialism as they existed, where coercion, fear, and lack of freedom were intertwined with ideals, group ethics, friendship, creativity, and concern for the future, Yurchak attempts to reflect on life under Soviet socialism and “rehumanize” Soviet subjectivity, which has been denigrated with terms like “homo sovieticus.”

This book goes beyond simply explaining a single, concrete event—the “sudden demise of the Soviet Union”—and offers a new approach to how systemic crises unfold and are experienced.

The once “eternal” Soviet landscape offers profound food for thought for us today, living in a sense of permanence where no alternative is possible and nothing will fundamentally change, no matter what we do.

“I had the complete impression that everything would last forever.”

In 2005, Alexei Yurchak's Everything Was Forever, Until It Was Gone was published in the United States, causing a stir in academic circles and sparking a boom in cultural studies of the late Soviet era.

As the title implies, the collapse of the Soviet system was “unforeseeable and unimaginable until it happened, but once it did begin, it was experienced as a perfectly logical and exciting event.”

“I realized that people had always been preparing for the collapse of the system without even realizing it, and that life under socialism was formed by interesting paradoxes.” This book aims to question conventional assumptions about the way people who lived under Soviet socialism related to reality and to elucidate this paradox that lies at the very heart of the Soviet system.

By showing the realities of socialism as they existed, where coercion, fear, and lack of freedom were intertwined with ideals, group ethics, friendship, creativity, and concern for the future, Yurchak attempts to reflect on life under Soviet socialism and “rehumanize” Soviet subjectivity, which has been denigrated with terms like “homo sovieticus.”

This book goes beyond simply explaining a single, concrete event—the “sudden demise of the Soviet Union”—and offers a new approach to how systemic crises unfold and are experienced.

The once “eternal” Soviet landscape offers profound food for thought for us today, living in a sense of permanence where no alternative is possible and nothing will fundamentally change, no matter what we do.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Chapter 1: Post-Socialism: The Eternal Empire

Hegemony in Chapter 2: Stalin's Chilling Paradigm Shift

Chapter 3: Inverted Ideology: Ethics and Poetics

Chapter 4 Living in 'Bny': Deterritorialized Social Environments

Chapter 5: The Imaginary West: Beyond Post-Socialism

Chapter 6: The True Colors of Communism: King Crimson, Deep Purple, and Pink Floyd

Chapter 7 Dead Irony: Necromancy, Stomps, and Anekdots

conclusion

References

Search

Translator's Note

Hegemony in Chapter 2: Stalin's Chilling Paradigm Shift

Chapter 3: Inverted Ideology: Ethics and Poetics

Chapter 4 Living in 'Bny': Deterritorialized Social Environments

Chapter 5: The Imaginary West: Beyond Post-Socialism

Chapter 6: The True Colors of Communism: King Crimson, Deep Purple, and Pink Floyd

Chapter 7 Dead Irony: Necromancy, Stomps, and Anekdots

conclusion

References

Search

Translator's Note

Into the book

The Soviet system caused immense suffering, oppression, fear, and lack of freedom, and the records of this remain intact.

But if we emphasize only this aspect of the system, it will be difficult to fully answer the questions we raise in this book about the internal paradoxes of life under socialism.

Dualistic explanations often miss the following crucial and seemingly paradoxical fact:

It is true that for the vast majority of Soviet citizens, many of the fundamental values, ideals, and realities of socialist life—equality, community, dedication, altruism, friendship, ethical relationships, security, education, work, creativity, concern for the future, and so on—were genuinely important.

--- p.24

Soviet citizens were expected to be enlightened individuals with an independent mind, who were expected to be inquisitive, creative, and knowledge-seeking, while maintaining complete loyalty to the Party's power, a collectivist ethic, and a restraint on individualism.

This Soviet version of the paradox of reportage did not develop by chance, but grew out of the revolutionary project itself.

--- p.29

Boiler room technicians had to be in the boiler room all the time, but there was little for them to do inside.

They worked in 24-hour shifts, once every four days.

The salary was very low (60-70 rubles a month, the lowest among public sector wages), but the job offered a tremendous amount of free time.

[…] Many 'amateur' rock musicians had this job, and they were slangly called "boiler room rockers".

[…] At the time, this occupation was so common that the famous rock group Arkbarium sang a song about their colleagues, “the generation of street cleaners and night watchmen.”

--- p.290~292

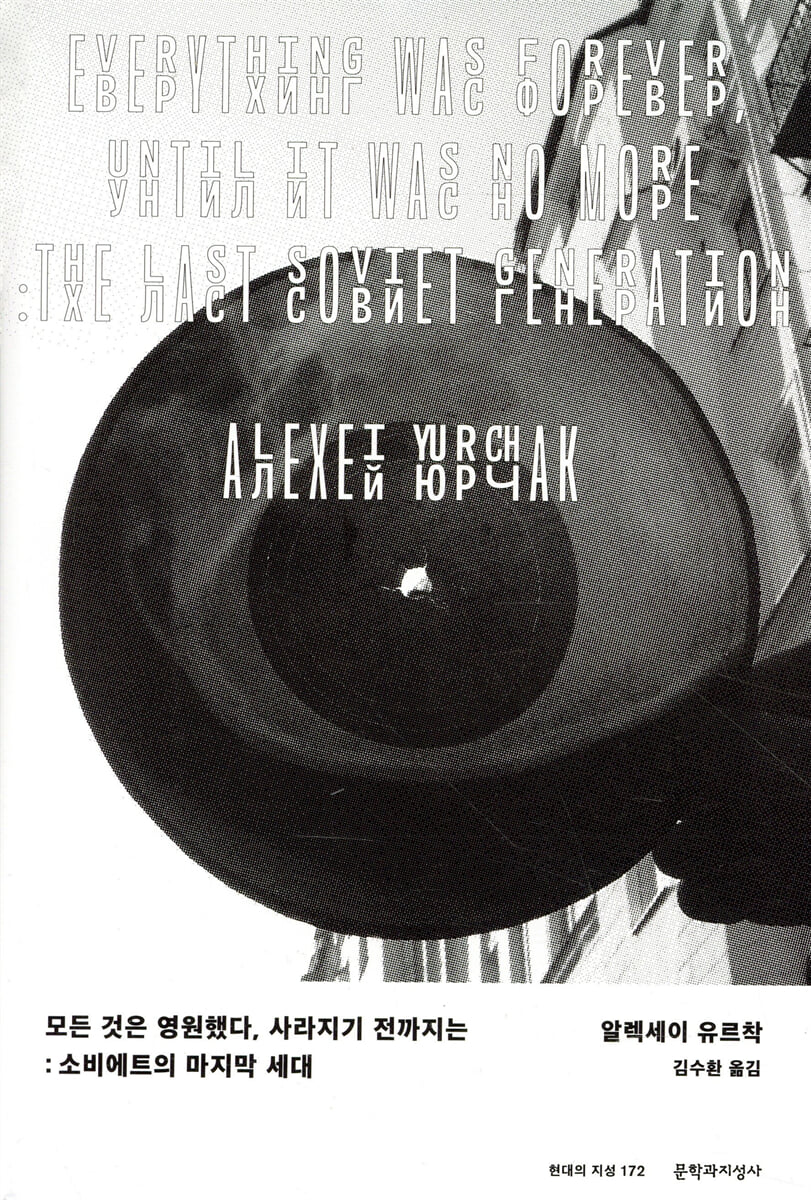

Demand for Western jazz and rock 'n' roll soared, but Soviet state-run record stores couldn't find it.

This led to the invention of an independent music duplication technology called the vinyl record.

Original Western records containing jazz and rock 'n' roll were copied onto used plastic X-ray plates, giving rise to the curiously nicknamed "rock on the bone".

[…] The strange materiality of 'rock on bone' and the obvious metaphors these X-ray plates evoked had quite an effect on Soviet fans.

These records sparked a humorous discussion that shaped the imagination of the West in two directions.

--- pp.344~345

Around 1980, a peculiar group of artists called Mit'ki appeared in Leningrad.

Members of this group transformed their everyday lives into aesthetic projects through performative practices of living in grotesque ways within and outside the sociopolitical concerns of the system.

[…] In fact, the real Mitok doesn't even know about two neighborhood stores: a bar and a bakery.

The fact that Mitki makes no effort to seek out such knowledge means that they continue to play the role of the unconscious, friendly, and all-embracing slacker, completely ignoring the usual concerns of career, success, money, beauty, and health.

--- po.445~446

Avia overidentified herself with the enthusiastic propaganda tradition of Soviet ideology throughout various periods, decontextualizing it by mixing the optimistic avant-garde aesthetics of the 1920s with the ossified ideological forms of the stagnant 1970s, with elements of punk and somewhat erotic cabaret.

In Abia's performance, up to twenty actors, wearing workers' overalls, chant slogans and cheers, march in a column with enthusiasm, and build human pyramids.

In their role as “young builders of communism,” they appear so cheerful and enthusiastic that at times they border on madness.

In the late 1980s, while working as Abia's manager, I witnessed audience reactions. Many in the audience for Laibach and Abia's performances, especially the older generation and foreigners, were at a loss as to how to interpret these happenings, often jumping to completely contradictory interpretations.

--- pp.473~474

When the changes brought about by perestroika made it no longer important or possible to reproduce the experience of the system's immutability, the paradoxical processes of late socialism also became untenable.

At the same time, the early changes of perestroika decisively revealed and exposed something that had long since become part of everyone's everyday life but had managed to remain unspoken through the grand narrative: something that enabled everyone to remain involved in the constant transformation of the system through their unanimous participation in its institutions, rituals, discourses, and lifestyles.

--- p.529

Doesn't this sense that the present will last forever, that nothing will change fundamentally, no matter what we do, feel vaguely familiar? The strange resonance that everyday life in the "post-" socialist Soviet era creates with our lives "after" modernity is worth pondering.

This strange sense of stability that seems to never end, this permanence in which system malfunctions become so commonplace that even full operation makes the system unstable, cannot possibly continue in the same way forever.

But if we emphasize only this aspect of the system, it will be difficult to fully answer the questions we raise in this book about the internal paradoxes of life under socialism.

Dualistic explanations often miss the following crucial and seemingly paradoxical fact:

It is true that for the vast majority of Soviet citizens, many of the fundamental values, ideals, and realities of socialist life—equality, community, dedication, altruism, friendship, ethical relationships, security, education, work, creativity, concern for the future, and so on—were genuinely important.

--- p.24

Soviet citizens were expected to be enlightened individuals with an independent mind, who were expected to be inquisitive, creative, and knowledge-seeking, while maintaining complete loyalty to the Party's power, a collectivist ethic, and a restraint on individualism.

This Soviet version of the paradox of reportage did not develop by chance, but grew out of the revolutionary project itself.

--- p.29

Boiler room technicians had to be in the boiler room all the time, but there was little for them to do inside.

They worked in 24-hour shifts, once every four days.

The salary was very low (60-70 rubles a month, the lowest among public sector wages), but the job offered a tremendous amount of free time.

[…] Many 'amateur' rock musicians had this job, and they were slangly called "boiler room rockers".

[…] At the time, this occupation was so common that the famous rock group Arkbarium sang a song about their colleagues, “the generation of street cleaners and night watchmen.”

--- p.290~292

Demand for Western jazz and rock 'n' roll soared, but Soviet state-run record stores couldn't find it.

This led to the invention of an independent music duplication technology called the vinyl record.

Original Western records containing jazz and rock 'n' roll were copied onto used plastic X-ray plates, giving rise to the curiously nicknamed "rock on the bone".

[…] The strange materiality of 'rock on bone' and the obvious metaphors these X-ray plates evoked had quite an effect on Soviet fans.

These records sparked a humorous discussion that shaped the imagination of the West in two directions.

--- pp.344~345

Around 1980, a peculiar group of artists called Mit'ki appeared in Leningrad.

Members of this group transformed their everyday lives into aesthetic projects through performative practices of living in grotesque ways within and outside the sociopolitical concerns of the system.

[…] In fact, the real Mitok doesn't even know about two neighborhood stores: a bar and a bakery.

The fact that Mitki makes no effort to seek out such knowledge means that they continue to play the role of the unconscious, friendly, and all-embracing slacker, completely ignoring the usual concerns of career, success, money, beauty, and health.

--- po.445~446

Avia overidentified herself with the enthusiastic propaganda tradition of Soviet ideology throughout various periods, decontextualizing it by mixing the optimistic avant-garde aesthetics of the 1920s with the ossified ideological forms of the stagnant 1970s, with elements of punk and somewhat erotic cabaret.

In Abia's performance, up to twenty actors, wearing workers' overalls, chant slogans and cheers, march in a column with enthusiasm, and build human pyramids.

In their role as “young builders of communism,” they appear so cheerful and enthusiastic that at times they border on madness.

In the late 1980s, while working as Abia's manager, I witnessed audience reactions. Many in the audience for Laibach and Abia's performances, especially the older generation and foreigners, were at a loss as to how to interpret these happenings, often jumping to completely contradictory interpretations.

--- pp.473~474

When the changes brought about by perestroika made it no longer important or possible to reproduce the experience of the system's immutability, the paradoxical processes of late socialism also became untenable.

At the same time, the early changes of perestroika decisively revealed and exposed something that had long since become part of everyone's everyday life but had managed to remain unspoken through the grand narrative: something that enabled everyone to remain involved in the constant transformation of the system through their unanimous participation in its institutions, rituals, discourses, and lifestyles.

--- p.529

Doesn't this sense that the present will last forever, that nothing will change fundamentally, no matter what we do, feel vaguely familiar? The strange resonance that everyday life in the "post-" socialist Soviet era creates with our lives "after" modernity is worth pondering.

This strange sense of stability that seems to never end, this permanence in which system malfunctions become so commonplace that even full operation makes the system unstable, cannot possibly continue in the same way forever.

--- p.633, from the 'Translator's Note'

Publisher's Review

Post-socialism, or

An exploration of a time when life was thought to last forever

The book explores a period the author calls “late socialism,” spanning roughly three decades from the mid-1950s to the mid-1980s (from the Khrushchev thaw to the Brezhnev stagnation).

This was before the changes brought about by perestroika, a time when the system was still thought to last forever.

Among these, Yurchak pays particular attention to the lives of the “last Soviet generation,” those who spent their youth during the Brezhnev era and who experienced the unique paradoxes of the Soviet system more intensely than any other generation.

With the death of Stalin, the “meta-discourse” that had been the standard for ideological discourse disappeared, creating a situation in which all expressions could be seen as anti-normative, leading to an obsession with fixed and formalized discourse.

This “normalization” has become an end in itself, and the reproduction of normative forms has taken place in all areas of discourse (posters, films, monuments, rallies, reports, commemorative events, school curricula, the organization of urban space).

In this way, the performative dimension of the speech act becomes more important and the declarative meaning of discourse is weakened. Yurchak explains that this “performative turn” is the core principle that operated authoritative discourse and reproduced and organized practice in late socialism.

The weakening of the declarative dimension does not mean that discourse has become an “empty” ritual.

On the contrary, the possibility of unpredictable and indeterminate interpretations, that is, creative reinterpretations of socialist life, has opened up, without the need to be bound by bureaucratic interpretations of declarative meaning.

About “normal life” in some “eternal” world

But what is important here is that these things did not happen 'against' or 'outside' the official Soviet discourse and protocol.

Yurchak explains that for the vast majority of Soviet people, the fundamental values and ideology of socialist life were truly important, and that as “normal people” who believed in the values of the system and lived as part of it participated in the process of reproducing discourse and ritual, various forms of meaningful and creative life spaces opened up.

It was not “dissidents,” as is commonly assumed, but ordinary Soviet people who carried out the work of “deterritorialization” that opened up a space-time of deviation at the heart of the system.

And it was the Soviet system itself that made this colorful life possible!

This book presents a wealth of fascinating episodes that showcase creative deviation and appropriation, from the story of a Komsomol secretary who combined communist ideals with the values of rock music, to rock musicians and doctors who voluntarily became boilermen, to the aesthetics of absurd humor and irony that permeated everyday life in the 1970s and 1980s, to the bizarre performances of artists.

Yurchak argues that these seemingly contradictory situations were not exceptions to the 'norm' of late Soviet life, but rather typical examples of how norms were decentered and reinterpreted everywhere.

So how did this paradoxical society come to an end?

According to Yurchak, the process of perestroika meant, above all, the dismantling of Soviet authoritarian discourse.

The collapse of the party through reform led to the collapse of the discourse of power, and thus the performative reproduction of authoritarian discourse became impossible, as did the creative reappropriation it entailed.

A change in the conditions of discourse has in an instant brought down a system that seemed destined to last forever.

The significance of this book

While it is fascinating to follow Yurchak's theoretical discussion of the inherent conditions of the Soviet system that so quickly transformed the sense of its permanence into an acceptance of the naturalness of its collapse, it is also a pleasure in itself to read the vast amount of anthropological material he has unleashed to do so.

The material Yurchak covers is vast, ranging from private materials from the late Soviet period (letters, notes, diaries, music, amateur films, etc.) that provide insight into the contemporary perspective, to official Soviet publications (speeches, newspapers, films, photographs, comics, etc.), to various interviews, memoirs, and broadcasts mass-produced during and after Perestroika.

Beyond reconstructing the true nature of Soviet life through this book, we can also read it in relation to today's reality.

As Professor Kim Su-hwan, who translated this book, noted, “The strange resonance that the everyday life of the ‘late’ socialist Soviet Union creates with our lives living ‘after’ modern times is worth pondering.” The collapse of the Soviet Union is the closest experience of the ‘end’ that our time remembers.

It would be an important task of our time to understand what kind of premonition and shock that experience was accompanied by, and what kind of subjectivity was involved in the process of its downfall.

※ For this book, Yurchak received the Best Author Award from the Society for Slavic, East European and Eurasian Studies in the United States in 2007 and the Academic Author Award from the Dmitry Zhimin Foundation in Russia in 2015.

He was also evaluated as having made the 'Brezhnev period' a new center of Soviet cultural studies, following the revolutionary, Stalinist, and Thaw periods.

The book's influence was not limited to the academic field.

British documentary director Adam Curtis's film "Hypernormalization" and director Kirill Serebrennikov's film "Leto" are also known to have been directly or indirectly influenced by Yurchak's research, and traces of Yurchak can be found in the works of many other artists.

※ The 'X-ray record' used on the cover of this book was taken by Yurchak himself, and can be said to be an excellent metaphor for this book.

This X-ray record, a homemade recording of Western music on an X-ray plate, “encapsulates the paradoxical situation in which the bones and arteries of the Soviet body provide an intimate space for alien sounds coming from beyond.”

An exploration of a time when life was thought to last forever

The book explores a period the author calls “late socialism,” spanning roughly three decades from the mid-1950s to the mid-1980s (from the Khrushchev thaw to the Brezhnev stagnation).

This was before the changes brought about by perestroika, a time when the system was still thought to last forever.

Among these, Yurchak pays particular attention to the lives of the “last Soviet generation,” those who spent their youth during the Brezhnev era and who experienced the unique paradoxes of the Soviet system more intensely than any other generation.

With the death of Stalin, the “meta-discourse” that had been the standard for ideological discourse disappeared, creating a situation in which all expressions could be seen as anti-normative, leading to an obsession with fixed and formalized discourse.

This “normalization” has become an end in itself, and the reproduction of normative forms has taken place in all areas of discourse (posters, films, monuments, rallies, reports, commemorative events, school curricula, the organization of urban space).

In this way, the performative dimension of the speech act becomes more important and the declarative meaning of discourse is weakened. Yurchak explains that this “performative turn” is the core principle that operated authoritative discourse and reproduced and organized practice in late socialism.

The weakening of the declarative dimension does not mean that discourse has become an “empty” ritual.

On the contrary, the possibility of unpredictable and indeterminate interpretations, that is, creative reinterpretations of socialist life, has opened up, without the need to be bound by bureaucratic interpretations of declarative meaning.

About “normal life” in some “eternal” world

But what is important here is that these things did not happen 'against' or 'outside' the official Soviet discourse and protocol.

Yurchak explains that for the vast majority of Soviet people, the fundamental values and ideology of socialist life were truly important, and that as “normal people” who believed in the values of the system and lived as part of it participated in the process of reproducing discourse and ritual, various forms of meaningful and creative life spaces opened up.

It was not “dissidents,” as is commonly assumed, but ordinary Soviet people who carried out the work of “deterritorialization” that opened up a space-time of deviation at the heart of the system.

And it was the Soviet system itself that made this colorful life possible!

This book presents a wealth of fascinating episodes that showcase creative deviation and appropriation, from the story of a Komsomol secretary who combined communist ideals with the values of rock music, to rock musicians and doctors who voluntarily became boilermen, to the aesthetics of absurd humor and irony that permeated everyday life in the 1970s and 1980s, to the bizarre performances of artists.

Yurchak argues that these seemingly contradictory situations were not exceptions to the 'norm' of late Soviet life, but rather typical examples of how norms were decentered and reinterpreted everywhere.

So how did this paradoxical society come to an end?

According to Yurchak, the process of perestroika meant, above all, the dismantling of Soviet authoritarian discourse.

The collapse of the party through reform led to the collapse of the discourse of power, and thus the performative reproduction of authoritarian discourse became impossible, as did the creative reappropriation it entailed.

A change in the conditions of discourse has in an instant brought down a system that seemed destined to last forever.

The significance of this book

While it is fascinating to follow Yurchak's theoretical discussion of the inherent conditions of the Soviet system that so quickly transformed the sense of its permanence into an acceptance of the naturalness of its collapse, it is also a pleasure in itself to read the vast amount of anthropological material he has unleashed to do so.

The material Yurchak covers is vast, ranging from private materials from the late Soviet period (letters, notes, diaries, music, amateur films, etc.) that provide insight into the contemporary perspective, to official Soviet publications (speeches, newspapers, films, photographs, comics, etc.), to various interviews, memoirs, and broadcasts mass-produced during and after Perestroika.

Beyond reconstructing the true nature of Soviet life through this book, we can also read it in relation to today's reality.

As Professor Kim Su-hwan, who translated this book, noted, “The strange resonance that the everyday life of the ‘late’ socialist Soviet Union creates with our lives living ‘after’ modern times is worth pondering.” The collapse of the Soviet Union is the closest experience of the ‘end’ that our time remembers.

It would be an important task of our time to understand what kind of premonition and shock that experience was accompanied by, and what kind of subjectivity was involved in the process of its downfall.

※ For this book, Yurchak received the Best Author Award from the Society for Slavic, East European and Eurasian Studies in the United States in 2007 and the Academic Author Award from the Dmitry Zhimin Foundation in Russia in 2015.

He was also evaluated as having made the 'Brezhnev period' a new center of Soviet cultural studies, following the revolutionary, Stalinist, and Thaw periods.

The book's influence was not limited to the academic field.

British documentary director Adam Curtis's film "Hypernormalization" and director Kirill Serebrennikov's film "Leto" are also known to have been directly or indirectly influenced by Yurchak's research, and traces of Yurchak can be found in the works of many other artists.

※ The 'X-ray record' used on the cover of this book was taken by Yurchak himself, and can be said to be an excellent metaphor for this book.

This X-ray record, a homemade recording of Western music on an X-ray plate, “encapsulates the paradoxical situation in which the bones and arteries of the Soviet body provide an intimate space for alien sounds coming from beyond.”

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: September 30, 2019

- Page count, weight, size: 640 pages | 904g | 153*224*35mm

- ISBN13: 9788932035758

- ISBN10: 893203575X

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)