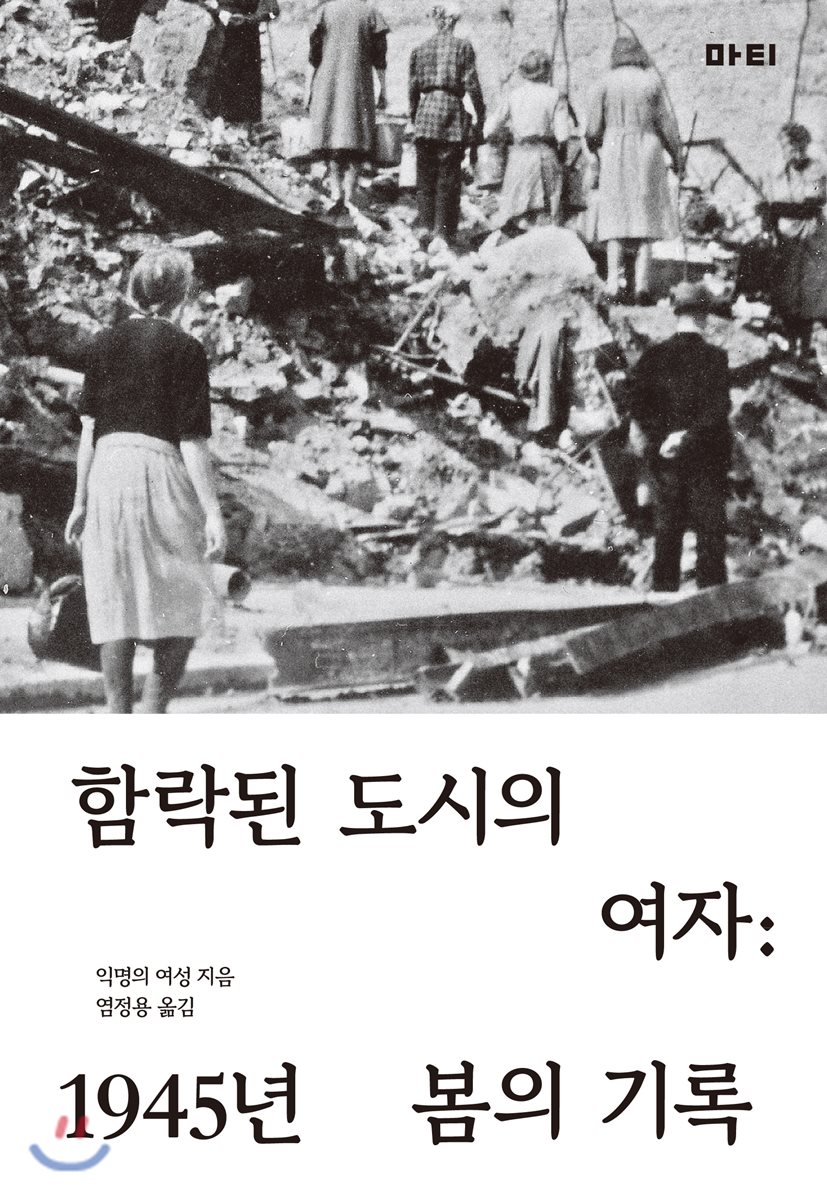

Women of the Fallen City

|

Description

Book Introduction

In April 1945, towards the end of World War II, Berlin falls to the Russian army.

A woman wrote a diary about Berlin at that time.

This book, compiled from her diary, is a meticulous historical record of the Fall of Berlin and a testimony to the double suffering women endured during the war.

A woman wrote a diary about Berlin at that time.

This book, compiled from her diary, is a meticulous historical record of the Fall of Berlin and a testimony to the double suffering women endured during the war.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

German edition publisher's preface

Diary, April 20, 1945 - June 22, 1945

German edition publisher's review

Korean edition publisher's review

Major events of World War II in 1945

Diary, April 20, 1945 - June 22, 1945

German edition publisher's review

Korean edition publisher's review

Major events of World War II in 1945

Publisher's Review

In the spring of 1945, as World War II was drawing to a close,

Berlin, a city left only for women

A woman writes a diary of Berlin at this time.

In 1939, when the war broke out, Berlin's population was 4.32 million.

During the six years of war, the population continued to decline due to refugees and participation in the war, and it is estimated that only 2.7 million civilians remained in Berlin in 1945.

And 2 million of them were women.

Berlin had become a 'city of only women'.

A woman wrote a diary about Berlin at that time.

It was a record of the period from April 20, 1945, when the Eastern Front was closing in so that flames were visible rising east of Berlin, until June 22, before the Russian army captured the city and the Allies began negotiations over Berlin.

According to the diary, the author is a “pale blonde woman” and “a publisher’s employee” (p. 20).

After losing his home in a bombing, he moved into the attic of a former coworker who had gone to the front, and found a notebook on a bookshelf there, where he began writing a diary.

Stories of women who had no choice but to turn their bodies into battlefields.

On Friday, April 27th, the day the Russian army began to turn the corner, the vaguely referred to incident known as “that thing” first appears in the diary.

The “thing” that appears almost daily in the eight weeks that follow is rape.

Women's greetings now turned into questions like, "How many times have you...?" (p. 200), and few women were able to avoid the indiscriminate sexual violence of Russian soldiers.

The author says:

“We now view sexual violence as a collective experience.

“Sexual violence is now happening everywhere and has even become a subject of negotiation.” (p. 181)

That's right.

After the German government cut off food rations, many women deliberately slept with Russian soldiers who could provide them with food.

The author also devises a survival strategy to prevent repeated rapes (p. 84). Whenever the author "succeeds" in establishing a relationship with a Russian officer, a middle-aged woman (the "widow" in the diary) who becomes the author's roommate secretly calculates her "price" (p. 236, 281).

It is known that mass rapes of German women by Allied forces, including Russian forces, during World War II were serious.

Post-war studies estimate that up to one million women were raped across Germany, with between 95,000 and 110,000 victims in Berlin alone.

This diary is a vivid testimony that shows one aspect of the 'Berlin Gang Rape Incident' and a record of the suffering women had to endure because they were women during the war.

Gazing at the lives ruined by war

The author confesses that he wrote to take care of himself, but he also observes the daily lives of those left behind with a cool eye and writes about them in detail.

The process of family ties becoming meaningless, the emergence and disappearance of survivor communities, the despair when even Germans did not hesitate to loot each other, the strange moments when courage suddenly arises and they take risks for others after turning a blind eye to the suffering of their neighbors, the constant hunger and the intense desire for food, the anxiety about pregnancy from rape, forced labor, and the anger toward the government that perpetuates false propaganda… The joy of walking and walking through the desolate streets in search of acquaintances with whom I was not very close before the war, and finally meeting them.

This diary contains unfamiliar emotions that humans cannot feel in normal times.

The pain that the invading nation, Germany, could not bring itself to reveal

The complexities of being a German victim

The diary clearly shows how complex the position of a 'German victim' of World War II was for an individual.

The writer could only listen quietly as a soldier, who was stopped by an officer from raping a German woman, protested, “What did the Germans do to our women?”

There was also a Russian soldier who claimed that “the Germans stabbed the children to death, grabbed the children by the ankles and smashed their heads against the wall.”

The women strongly deny that it was the work of the 'Nazi SS' and that it could not have been done by the regular army to which their husbands belonged.

But the writer always takes a step back and faces reality in the face of his own suffering and the suffering of others.

“Our conquerors, whether regular troops or SS, will simply consider us ‘Germans’ and hold us all accountable.” The author repeatedly reminds himself that he is German.

He recalls his brief involvement with the Nazis and his fascination with communism, and struggles to accept the weight of history that each individual must bear.

“Not everyone is guilty, but everyone is responsible.” This attitude of the German government in reflecting on the Holocaust and wars of aggression is based on the reflections of individuals like the woman who wrote this diary.

After the controversy over forgery, it became evidence of tragedy.

This diary was initially a jumble of short notes, abbreviations, hints, words, and fragmentary thoughts.

The author is known to have typewritten this in July 1945, polishing the expressions and later revising it by supplementing his observations and thoughts.

In this way, a 121-page manuscript on gray military paper was completed.

After the war, the German writer Kurt W. Marek, an acquaintance of the author,

Marek) persuaded the author to publish, and the author accepted on condition of anonymity.

It was first published in the United States in 1954 under the title A Woman in Berlin, and was later translated and introduced in eight languages.

However, in Germany, which had no capacity to heal the wounds of the post-war period, it was only published in 2002.

Meanwhile, it was revealed that the author of this diary was Marta Hillers.

She worked as a photojournalist during the war and contributed to several magazines.

After marrying a Swiss man and emigrating in the 1950s, she has not been active in official activities.

Died in 2001 at the age of 90

A few years ago, she revisited the manuscript she had written in 1945 and made a few minor corrections.

《Women of the Fallen City》 is a translation of the German edition published based on the final proofreading.

Filling the blank pages of World War II with women's voices

One day, the writer wrote in his diary, “For the first time since the war, I wonder if I am qualified to be a witness.”

What qualifications are needed to become a witness to history?

More than Albert Speer, Hitler's architect who was the only high-ranking official who collaborated with the Nazi regime to escape execution at the war crimes trial and leave behind memoirs, or Brunhilde Pomsel, Goebbels' secretary who claimed she knew nothing and was just an honest young man, the anonymous women whose bodies became battlefields are also witnesses of that era.

Berlin, a city left only for women

A woman writes a diary of Berlin at this time.

In 1939, when the war broke out, Berlin's population was 4.32 million.

During the six years of war, the population continued to decline due to refugees and participation in the war, and it is estimated that only 2.7 million civilians remained in Berlin in 1945.

And 2 million of them were women.

Berlin had become a 'city of only women'.

A woman wrote a diary about Berlin at that time.

It was a record of the period from April 20, 1945, when the Eastern Front was closing in so that flames were visible rising east of Berlin, until June 22, before the Russian army captured the city and the Allies began negotiations over Berlin.

According to the diary, the author is a “pale blonde woman” and “a publisher’s employee” (p. 20).

After losing his home in a bombing, he moved into the attic of a former coworker who had gone to the front, and found a notebook on a bookshelf there, where he began writing a diary.

Stories of women who had no choice but to turn their bodies into battlefields.

On Friday, April 27th, the day the Russian army began to turn the corner, the vaguely referred to incident known as “that thing” first appears in the diary.

The “thing” that appears almost daily in the eight weeks that follow is rape.

Women's greetings now turned into questions like, "How many times have you...?" (p. 200), and few women were able to avoid the indiscriminate sexual violence of Russian soldiers.

The author says:

“We now view sexual violence as a collective experience.

“Sexual violence is now happening everywhere and has even become a subject of negotiation.” (p. 181)

That's right.

After the German government cut off food rations, many women deliberately slept with Russian soldiers who could provide them with food.

The author also devises a survival strategy to prevent repeated rapes (p. 84). Whenever the author "succeeds" in establishing a relationship with a Russian officer, a middle-aged woman (the "widow" in the diary) who becomes the author's roommate secretly calculates her "price" (p. 236, 281).

It is known that mass rapes of German women by Allied forces, including Russian forces, during World War II were serious.

Post-war studies estimate that up to one million women were raped across Germany, with between 95,000 and 110,000 victims in Berlin alone.

This diary is a vivid testimony that shows one aspect of the 'Berlin Gang Rape Incident' and a record of the suffering women had to endure because they were women during the war.

Gazing at the lives ruined by war

The author confesses that he wrote to take care of himself, but he also observes the daily lives of those left behind with a cool eye and writes about them in detail.

The process of family ties becoming meaningless, the emergence and disappearance of survivor communities, the despair when even Germans did not hesitate to loot each other, the strange moments when courage suddenly arises and they take risks for others after turning a blind eye to the suffering of their neighbors, the constant hunger and the intense desire for food, the anxiety about pregnancy from rape, forced labor, and the anger toward the government that perpetuates false propaganda… The joy of walking and walking through the desolate streets in search of acquaintances with whom I was not very close before the war, and finally meeting them.

This diary contains unfamiliar emotions that humans cannot feel in normal times.

The pain that the invading nation, Germany, could not bring itself to reveal

The complexities of being a German victim

The diary clearly shows how complex the position of a 'German victim' of World War II was for an individual.

The writer could only listen quietly as a soldier, who was stopped by an officer from raping a German woman, protested, “What did the Germans do to our women?”

There was also a Russian soldier who claimed that “the Germans stabbed the children to death, grabbed the children by the ankles and smashed their heads against the wall.”

The women strongly deny that it was the work of the 'Nazi SS' and that it could not have been done by the regular army to which their husbands belonged.

But the writer always takes a step back and faces reality in the face of his own suffering and the suffering of others.

“Our conquerors, whether regular troops or SS, will simply consider us ‘Germans’ and hold us all accountable.” The author repeatedly reminds himself that he is German.

He recalls his brief involvement with the Nazis and his fascination with communism, and struggles to accept the weight of history that each individual must bear.

“Not everyone is guilty, but everyone is responsible.” This attitude of the German government in reflecting on the Holocaust and wars of aggression is based on the reflections of individuals like the woman who wrote this diary.

After the controversy over forgery, it became evidence of tragedy.

This diary was initially a jumble of short notes, abbreviations, hints, words, and fragmentary thoughts.

The author is known to have typewritten this in July 1945, polishing the expressions and later revising it by supplementing his observations and thoughts.

In this way, a 121-page manuscript on gray military paper was completed.

After the war, the German writer Kurt W. Marek, an acquaintance of the author,

Marek) persuaded the author to publish, and the author accepted on condition of anonymity.

It was first published in the United States in 1954 under the title A Woman in Berlin, and was later translated and introduced in eight languages.

However, in Germany, which had no capacity to heal the wounds of the post-war period, it was only published in 2002.

Meanwhile, it was revealed that the author of this diary was Marta Hillers.

She worked as a photojournalist during the war and contributed to several magazines.

After marrying a Swiss man and emigrating in the 1950s, she has not been active in official activities.

Died in 2001 at the age of 90

A few years ago, she revisited the manuscript she had written in 1945 and made a few minor corrections.

《Women of the Fallen City》 is a translation of the German edition published based on the final proofreading.

Filling the blank pages of World War II with women's voices

One day, the writer wrote in his diary, “For the first time since the war, I wonder if I am qualified to be a witness.”

What qualifications are needed to become a witness to history?

More than Albert Speer, Hitler's architect who was the only high-ranking official who collaborated with the Nazi regime to escape execution at the war crimes trial and leave behind memoirs, or Brunhilde Pomsel, Goebbels' secretary who claimed she knew nothing and was just an honest young man, the anonymous women whose bodies became battlefields are also witnesses of that era.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: August 30, 2016

- Page count, weight, size: 344 pages | 524g | 145*210*30mm

- ISBN13: 9791186000748

- ISBN10: 1186000740

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)