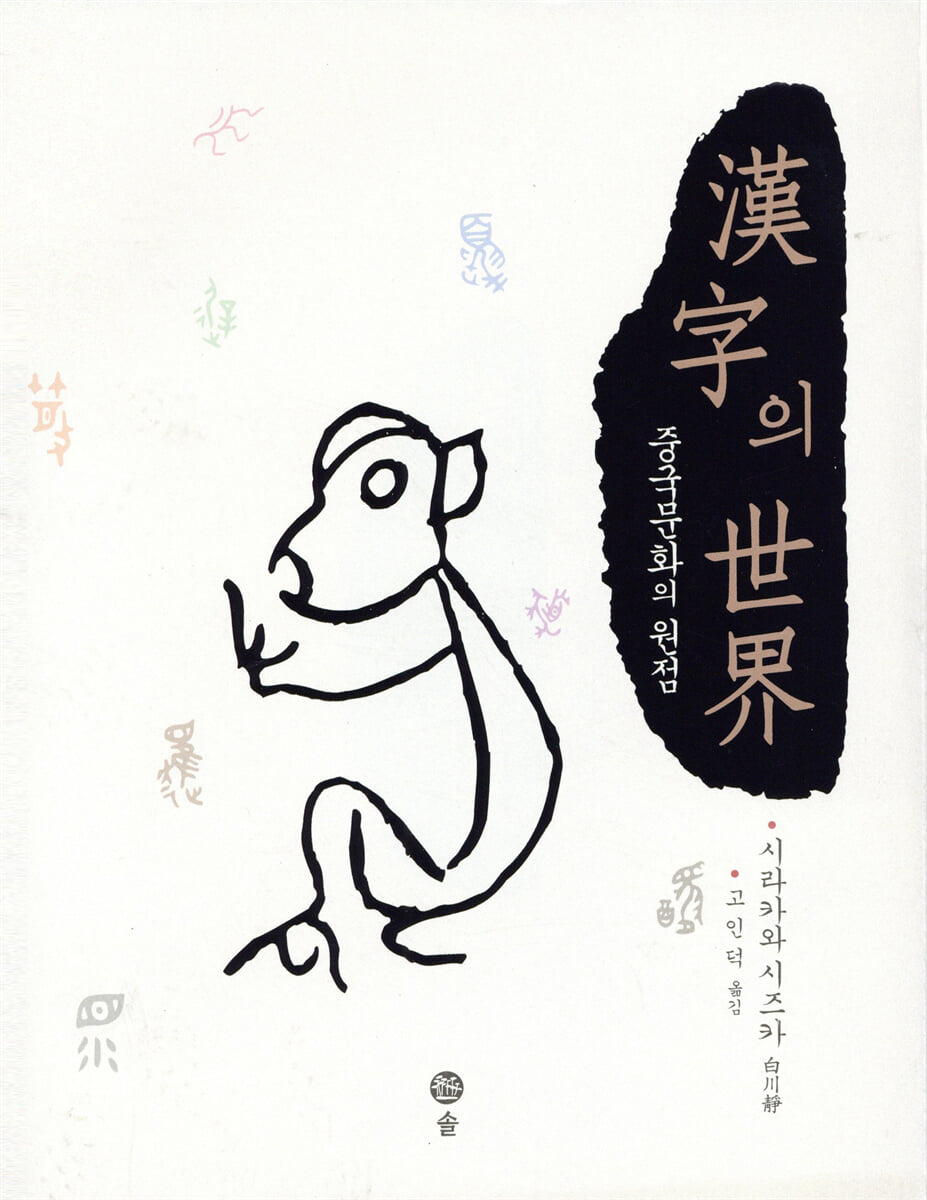

The World of Chinese Characters

|

Description

Book Introduction

This is a general explanation of the 1,460 Chinese characters that appear in oracle bone script and bronze inscriptions, categorized by problem-history, and grouped by type.

The author traces back to the origins of Chinese characters, using religiosity and sorcery as keywords, and reflects the latest archaeological and folkloristic achievements in the traditional Chinese character research system, crossing over the fields of Chinese character studies and archaeology.

This book argues that the Chinese characters, which are pictographic characters, are a writing system that was established on a long historical foundation before the so-called civilization, and that the world of the distant past, which has now disappeared through oral or written transmission, still has deep traces in the Chinese characters.

That is why we can unearth the antiquity behind ancient letters.

From this perspective, the entire book is divided into 12 chapters according to the lifestyle of the time when Chinese characters were created, and the related characters are interpreted. What runs through the entire book is, above all, the religiousness and magical nature of the society at the time.

The author traces back to the origins of Chinese characters, using religiosity and sorcery as keywords, and reflects the latest archaeological and folkloristic achievements in the traditional Chinese character research system, crossing over the fields of Chinese character studies and archaeology.

This book argues that the Chinese characters, which are pictographic characters, are a writing system that was established on a long historical foundation before the so-called civilization, and that the world of the distant past, which has now disappeared through oral or written transmission, still has deep traces in the Chinese characters.

That is why we can unearth the antiquity behind ancient letters.

From this perspective, the entire book is divided into 12 chapters according to the lifestyle of the time when Chinese characters were created, and the related characters are interpreted. What runs through the entire book is, above all, the religiousness and magical nature of the society at the time.

index

Part 1

Chapter 1: The Origin of Letters

The Origin of Chinese Characters | The Six Books and the Study of Characters | Literature | Characters and Names

Chapter 2: The Indivisible Principle

The Staff of God | Thoughts on the Left and Right | King Wu-chuk

Congratulations and Curses | Hidden Prayers | Mikotomochi [Local Official]

Chapter 3 Myths and Background

The Emperor's Messenger | The Celestial World | The River God and the Mountain God | The Land of the Four Evils

Chapter 4: Fear of the Two-legged Gods

The Curse of the Road | The Path of the Tamahoko

Chapter 5: On War

The Drummer | The Self-Governing Series | The Teacher and the Scholar | The Song of the Prisoner

Chapter 6 Primitive Religion

The World of Animism | Shamanism | The Origins of Song and Dance | About the Music God, Gi-Gyu

Part 2

Chapter 7: Faith in the Word

On Language | Miscellaneous Notes on the Language Department | Literature of Blessings | Books in the Golden Chest

Chapter 8: On Primitive Law

The Will of the Law | Ancient Trials | About Punishment | Rituals of Cultivation

Chapter 9: Holy Land and Places of Sacrifice

Takagi no Kami 高木の神 | The form of the shrine | About the offerings | Rituals of the Jongmyo Shrine | A devout young maiden

Chapter 10 Production and Technology

Forms of Production | Agricultural Rituals | The Establishment of Capitals | About Professional Craftsmen

Chapter 11 In the World

Family Relationships | Emotions and Expressions | Characters About the Human Body | About Medicine

Chapter 12: The Idea of Life

Expressing one's feelings through a scenic object | By attaching it to one's clothes | The Book of the Dead | Truth and Immortality

Translator's Note | Illustrations | References

Chapter 1: The Origin of Letters

The Origin of Chinese Characters | The Six Books and the Study of Characters | Literature | Characters and Names

Chapter 2: The Indivisible Principle

The Staff of God | Thoughts on the Left and Right | King Wu-chuk

Congratulations and Curses | Hidden Prayers | Mikotomochi [Local Official]

Chapter 3 Myths and Background

The Emperor's Messenger | The Celestial World | The River God and the Mountain God | The Land of the Four Evils

Chapter 4: Fear of the Two-legged Gods

The Curse of the Road | The Path of the Tamahoko

Chapter 5: On War

The Drummer | The Self-Governing Series | The Teacher and the Scholar | The Song of the Prisoner

Chapter 6 Primitive Religion

The World of Animism | Shamanism | The Origins of Song and Dance | About the Music God, Gi-Gyu

Part 2

Chapter 7: Faith in the Word

On Language | Miscellaneous Notes on the Language Department | Literature of Blessings | Books in the Golden Chest

Chapter 8: On Primitive Law

The Will of the Law | Ancient Trials | About Punishment | Rituals of Cultivation

Chapter 9: Holy Land and Places of Sacrifice

Takagi no Kami 高木の神 | The form of the shrine | About the offerings | Rituals of the Jongmyo Shrine | A devout young maiden

Chapter 10 Production and Technology

Forms of Production | Agricultural Rituals | The Establishment of Capitals | About Professional Craftsmen

Chapter 11 In the World

Family Relationships | Emotions and Expressions | Characters About the Human Body | About Medicine

Chapter 12: The Idea of Life

Expressing one's feelings through a scenic object | By attaching it to one's clothes | The Book of the Dead | Truth and Immortality

Translator's Note | Illustrations | References

Into the book

In China, it is known that Cangjie, the Yellow Emperor's historian, created Chinese characters.

In relation to this, in the “Benjingxun” of the “Huainanzi,” an encyclopedic work of the Former Han Dynasty, there is a record that says, “In ancient times, when Cangjie created letters, the sky dropped grain and ghosts cried at night.”

"Bon Kyung-hun" assumes that all creations based on human wisdom are a path to losing the innocence of the ancient past, and lists numerous tales about the origin of things, concluding with the words, "Intelligence increases more and more, and virtue decreases more and more."

This is a cultural view of history based on the Taoist philosophy of Lao-Zhuang. The heavens dropping grain signifies an abnormality, and the ghosts crying at night lament the fact that human wisdom has encroached on the power of the gods.

This also means that the naturally occurring spoken language became an artificially created written language, which was able to open up a free human mental world.

The era of ghosts is already over.

(Chapter 1: The Origin of Letters, p. 22)

The foundation for the study of Chinese characters' morphology was laid by Xu Xin's four-volume 『Shuowen Jiezi』 during the Later Han Dynasty.

The Seolmoohaeja is a book that provides a morphological explanation of 9,353 Chinese characters based on the compositional principles of the six Chinese characters.

Although the Six Books were already mentioned in the Hanshu 「Book of Han」「Records of Arts and Literature」 and Jeong Hyeon's commentary on the Zhouli, the Shuowen Jiezi is the first to explain their compositional principles.

The six books are hieroglyphs, instructions, meetings, sounds, introductory notes, and borrowing methods.

It is generally known that the first four types are methods of creating characters, and the last two types are methods of using the created characters, but the six books are all about the principles of character composition.

(Chapter 1: The Origin of Letters, p. 25)

Since the Spring and Autumn Period, names and characters have had related meanings.

The character of the person mentioned above is Yibo, which is related to the custom of the barbarians, tattooing.

Yan Hui, a disciple of Confucius, had the courtesy name Zi Yuan, and Yuan refers to a pond [Huishui].

Zeng Cham's courtesy name is Ziyeo, and his name, which is also read as Sam, is an abbreviated character of Cham [?: meaning to tie three horses to one cart], and both his name and courtesy name are related to carts [車輿].

Sam is the name of a star, so it should be read as Zeng Cham.

It is said that Meng Jia also called Ja Yu.

From this relationship of name and waiting, it is common in an age-based society that one must first have a name, but one is not recognized as a full member of a clan until one becomes an adult.

The name is given at the initiation ceremony to become a clan member, and until then, a baby name is used.

This is called a small letter.

The child is given a gift when performing a ritual to visit the ancestral shrine to report the work of raising the child to the spirit of the ancestors.

The character 字 is a character that represents such a shrine visit.

(Chapter 1: The Origin of Letters, pp. 62-63)

The god of drought is called Yeobal.

In the "Great Wild North Classic" of the "Classic of Mountains and Seas," it is said that in the Ji Kun Mountains of Da Huang, which are very far from China, there is a tower of Gong Gong, and there is a god dressed in blue who is said to be the daughter of the Yellow Emperor.

When Chiyou started a rebellion and led the Earl of Wind and the Master of Rain to attack, the emperor sent Lu Bal down to the earth to pacify the rebellion.

Later, it is said that Yeobal lost his way to heaven and that the place where he was was hit by a drought.

魃 is also written as ? and is the goddess of baldness.

The public domain where Yeobal lived is recorded in the “Overseas Beijing” section of the Shan Hai Jing as being north of Kunlun Mountain, and in ancient times, Sangryu, a subject of Gong Gong who failed to control floods and was killed, had nine human heads and the body of a snake and also lived here.

It is said that at the four corners of the public pavilion there are snakes with tiger stripes, their heads facing south.

This tower probably had a temple-like form similar to a ziggurat.

The god who failed to control the flood and the god of drought, Yeobal, are living together here.

(Chapter 2, The Inseparable Principle, p. 91)

The king also served as a shaman and presided over the ritual.

It was the king's job to judge the signs and determine good or bad fortune.

The king also supervised the ceremonies and offered many sacrifices.

The god that the king worshipped in this way was called the Emperor.

This absolute sovereign god is called Sangje, and in fact, in the copy, he said something like, “Will Sangje send down a drought?”

It was believed that the kings who became the ancestors of a dynasty were called after their deaths and accompanied the Shangdi on the left and right sides. The inscriptions on the bronze statues say, “The former kings solemnly stand on the Shangdi’s left and right sides,” and “The twelve are where the Shangdi is.”

The ancestral god is called the Lower Emperor, and these two are combined to be called the Upper and Lower Emperors.

The Supreme Being exercised complete dominion not only over the natural world but also over all things on earth, and he used the Baeksin gods to exercise this dominion.

The phrase "Emperor Huang and Baek Shin" appears in the Zong Zhou Zhong of the mid-Western Zhou Dynasty.

Even in the heavenly world, there was a strict order.

(Chapter 2, The Inseparable Principle, pp. 96-97)

Since there is no way to express the names of the directions specifically, they were expressed by borrowing sounds or relying on other means.

Dongdong is originally shaped like a pocket.

When the East was used only to mean direction, a separate character called Tak? was created.

The stone in this character is a sound talisman, and has the sound of tapping and tapping.

The shape of the character 東 is that of a tied pocket, that is, a pocket with tied top and bottom entrances.

In the 『Seomunhaeja』, the east is described as the sun [日] hanging in the middle of a tree [木], and the tree is the sacred tree of the east, Fusang [扶桑], and the sun rises from there, so it is interpreted based on the solar legend, but the shape of the old character is not like that.

It can be seen that all characters that include the shape of 東 have the meaning of pocket.

The same goes for the characters of the Bujeon lineage.

Among the characters created by the positions of 木 and 日, ? is “明” in the “Shuowen Haizi”.

It follows the meaning of the sun and is above the tree, and the myo is the shadow.

It is seen as indicating a temporal state by saying, “Following the meaning of the sun and under the tree,” but the structure of the character is completely different from that of the east.

(Chapter 3 Myths and Background, p. 131)

Along with the river, sacrifices to Akak were also popular.

Ak is thought to be the current Songshan Mountain in Hanam, and its old name was Ak.

The evil that stands tall on the plains of Hanam was once considered a sacred place for several clans with the surname Kang and was worshipped as their ancestral god.

In relation to this, in the “Sanggo” section of the “Book of Songs” it is written, “The towering peak is Ak, so high that it reaches the sky.

Evil sent down God and gave birth to Bo and Shin.

“Bo and Shin are the guardians of the Zhou,” he said.

Bo and Shin are considered to be descendants of the god of the mountains, and in addition, Heo and Je of the surname Kang, who later entered Shandong, are said to be the four kingdoms of the surname Kang.

All of these countries were founded by the descendants of evil spirits.

The countries with the surname Kang and the states with the surname Hee have had friendly relations for a long time.

The progenitor of the state is said to be Kang Won, and there is a birth story that he gave birth to Queen Ji by stepping in the footprints of a giant.

Even after entering the Spring and Autumn Period, the two surnames maintained a very close relationship, and in the “Yangzhi Shui” section of the “Book of Songs and the Wind of Kings”, it is recorded that Zhou dispatched troops to the three countries of Shen, Fu, and Xu to defend them against the threat of Chu in the south.

(Chapter 3 Myths and Background, pp. 161-162)

It is easy to see from the shapes of the characters "bang", "gyo", and "bian" that there was a custom in ancient China of offering up severed heads for sacrifice, and many surrounding ethnic groups also had customs of regarding skulls as magical objects.

The Wuhu people, who belonged to the Nanman barbarians, used to store wine in skulls, and Helian Bobo (the name of the king) of Daxia, who was said to be a descendant of the Xiongnu, gathered human heads together to make the arched gates of his military camps [capital gates].

Also, in Taiwan and other southern islands, the custom of making a pedestal [a skeleton-covered platform] or a shelf to place a skull on has long persisted.

Banishment is a ritual of exile, and exile is a spell of change. It was performed not only in the border areas, but also in the capital, sanctuaries, and places of worship.

(Chapter 4: Fear of Two-legged Gods, pp. 190-191)

In sacred buildings, an earth-shaking ritual was performed, and dogs were used as sacrifices.

In the 『Shuowen Zizi』, it is said that “Climbing to a high place”.

It takes the meaning of Gyeong and You.

It is interpreted as taking the sound and meaning of 尤, meaning “something that is especially outstanding compared to the average.”

In the text, 尤 is interpreted as meaning “will there be no disaster [尤]?” and 就 means sacrificing a dog in the Jeonki of Gyeonggwan.

The use of dogs for electricity and as sacrifices in sacred places can be inferred from the many dog sacrifices found in the ruins of Yin tombs and shrines, and can also be confirmed by the inclusion of dog sacrifices in related characters such as 家, chu, gi, hen, yu, etc.

(Chapter 4: Fear of Two-legged Gods, p. 197)

The word "氏" probably refers to a tool used for stabbing and cutting, which was used to cut up sacrifices and use them in rituals. Just as the person who handles sacrifices with a sharp tool at a ancestral shrine is called "jaejae," the word "氏" refers to a person in charge of handling sacrifices and presenting them for rituals.

Or, there may have been an instance where the name 氏 was used when making a blood oath.

That is, when making an oath, one drinks the blood of a sacrificial animal.

The sacred relic was probably placed in a temple.

In the 『Shuowen Zizi』, Gi is described as “the god of the earth.

It is said that “all things are sent out [Je-Chul-Chul]” and the meaning is interpreted by considering 祈 and Je as a combination of rhymes, and in the “Daejong-Baek” of the “Zhouli? Chun-Gwan” it is said to be “Heavenly gods, human ghosts, and earthly indications [Je-Chul-Chul].”

It can be thought that the reason why 祇 means the spirit of the earth is because the clan as a blood relative was connected through the spirit of the earth.

(Chapter 4: Fear of Two-legged Gods, p. 203)

During war, there were times when local music was played to determine God's will.

It was believed that God's will was also revealed in music.

The saying, “The songs of the southern Chu are not strong [南風不競]” seems to have originated from the Zuo Zhuan (18th year of Duke Yang’s reign).

In ancient times, Shi Guang, a musician of the Jin Dynasty, heard that the Chu army was going to attack, so he sang northern and southern songs to tell fortunes, and predicted that the Chu Dynasty would be defeated, saying, “The songs of the Chu Dynasty in the south are not strong and have many dead sounds.”

It may be for this reason that the 8th chapter of 『Sa-gwang』 in the 「Yemunji」 of 『Hanshu』 is placed in 「Bing-eum-yang」 in 「Bing-seo-ryak」.

Divining good or bad fortune by the sound of a song is the same way of thinking as thinking that victory or defeat can be determined by the sound of drums in a war.

(Chapter 5: On War, p. 231)

In the 『Shuowen Zhizi』, the word ‘學’ is written as 斅, and is interpreted as “覺悟이다” meaning ‘to realize’, but adding ‘복?’ here means to teach.

In the 『Shuowen Zhaizi』, 斅 is added to 敎, ? indicates ignorance, and 臼 is called a sound talisman.

The elements of the word ‘교’ (敎) are almost similar to ‘學’ (學), and in the ‘서문해자’ it is said to mean ‘to learn [효效]’ as it is “to learn from below what has been practiced above.”

All of them have ? as their brother and contain the meaning of teaching and admonishing, but 效, like 寅, has the shape of correcting 矢 by using si-ya as its component, and is a different character from 斅?敎.

In the 『Seolmunhaeja』, 效 is interpreted as “sang-i-da” meaning “to resemble” and is interpreted as meaning to reject [bin-cheok? 斥] 寅, which all mean to correct the arrow, and from this, the meaning of law?in-jeong (寅正) was created.

(Chapter 5 On War, p. 251)

In the 『Shuowen Zizi』, when it says about a song, “it is a song”, it means recitation.

In the 『Shuowen Zizi』, the character 欠 is interpreted as “imitating the shape of steam coming out of a person’s stomach,” and is shaped like a yawn. This character is shaped like an open mouth singing, and 歌 can be seen as the shape of singing, and 訶 can be seen as a word referring to lyrics.

In the 『Shuowen Zhizi』, 訶 is interpreted as “getting angry by making a sound like a horn,” but in the Jinwen, 歌 is written as 訶??, and 訶???歌 are all the same characters.

In short, all characters of the 可 series are close in sound and meaning, and are intended to rebuke God and make him grant what he desires.

(Chapter 6 Primitive Religion, p. 295)

The act of dancing in front of a shrine is called Ha-ha, and the song sung during a shrine ceremony is called Song.

In the 『Seomunhaeja』, it is said to be “shaped [mo?]” and is interpreted as a formative character that takes the sound of 公.

There are also letters that sound like 頌, such as 訟, that use 公 as a component, but these are all negative characters, and 公 honors the shrine where ancestors are worshipped.

In the 『Shuowen Zizi』, public is defined as “sharing equally” and the interpretation from the 『Han Feizi』「Five?」that “turning one’s back on private matters is called public.”

It is interpreted as meaning to turn one's back on one's own and eight on one's back, and the shape of the character for the gate and the gate of the gate represent the flat shape in front of the shrine.

It is thought that by the time of Han Feizi, knowledge of such ancient characters had already been lost.

As stated in “Xiao Xing” of “Book of Songs? Xiao Nan”, “From early morning until late at night, they are in the shrine [gong],” it refers to a shrine [gonggung] where ancestral rites are performed all day long.

All litigation within the clan was conducted at this shrine.

In the 『Seomunhaeja』, the word 訟 is defined as “a fight” and is interpreted as a character that takes the sound of public, meaning to swear in front of a shrine and decide the right or wrong.

Songdo means a song sung in front of a shrine.

(Chapter 6 Primitive Religion, pp. 314-315)

Words are a prayer, a vow to oneself, and a pledge to God.

While claiming to be clean and clear, he takes an aggressive stance against the other person.

In comparison, '어어' can be said to be a defensive word.

In the 『Shuowenhaizi』, the word 語 is said to be “론論이다”, in 論 it is said to be “의議이다”, and in 議 it is said to be “語是”, which are circular interpretations of meaning. The first meaning of 語 is in 吾.

That is, 語 is also the reverse sound of 吾.

In the 『Shuowenhaizi』, 吾 is considered a pronoun for self-appointment, as it is said to be “speaking of oneself,” and 五 is interpreted as a sound symbol. However, since there are no characters that are originally pronouns and they are all borrowed characters, 吾 must have had its original meaning.

(Chapter 7: Faith in the Word, p. 325)

In the 『Shuowen Haizi』, poetry is described as “志이다” and is interpreted as taking the sound of a temple.

In the past, it was a consonant that took the sound of 之, but either way, they are all consonants.

In the “Preface” of the “Mao Biography” of the “Book of Songs,” it is said, “Poetry is what one’s will is directed toward.

“What is in the heart becomes wisdom, and when it is expressed in words, it becomes poetry,” he said, adding that poetry is what wisdom is directed towards, that is, it expresses wisdom through song.

Ji is a character that takes the meaning of 之 and 心.

However, this is nothing more than a literal interpretation applied to literary theory, and it is not true that poetry, which expresses one's will in words, has existed since ancient times.

(Chapter 7: Faith in the Word, p. 345)

After King Goujian of Yue destroyed Wu, he became the sole ruler of the south. He lived a life of luxury with the peerless beauty Xi Shi as his wife. His ministers all wore silk and enjoyed a period of prosperity. However, Fan Li, who had helped him achieve his greatness, suddenly left the country.

His thought was that it is easy for people to share suffering, but not easy to share joy.

When he left, he changed his name to Chijapi? and arrived in the northern state of Qi by sea. He devoted himself to increasing his wealth and enjoyed a leisurely life away from politics.

The wealthy man known in the world as Tao Zhu Gong is his successor.

When Fan Li left the country of Yue, he changed his name to Chii Zi Pi, which is reminiscent of Wu Zixu being put into a chii and thrown into the river. Perhaps, when fleeing the country as an exile, it was necessary to take the form of a person abandoned by law.

It signified self-abandonment and was a courtesy when leaving the country.

(Chapter 8, On the Primitive Law, pp. 375-376)

A thief is not a small thief who drools and covets what is in a bowl.

He is a person who rejects the system and has fallen out of clan society.

The ming plate is a vessel that holds the document of oath, and signifies the oath as a member of a clan.

A thief is one who has abandoned the ties of his clan and has left the clan.

According to the shape of the character seen in the stone drum pattern of the Qin Dynasty, two water characters are added to the upper part of the character 盜.

Pouring water on a bowl can be seen as an act of dirtying the bowl.

The word 沓 is created by adding 水 to 曰, which means a document recording an oath between countries.

In the “Tenth Month Friendship” of the Book of Songs, the word “jun-dap” (沓) means a slanderous word.

Pouring water on the vessel used for the oath document or blood oath, thereby desecrating and cursing it, is an act of abandoning the clan bond and insulting the clan spirit.

To dare to do such a thing is theft.

The character 欠, which is included in the characters of 歐?歌 and other characters, means a curse.

Such defectors must be subject to legal sanctions by the divine grace.

That is, one must be “expelled from one’s fellows by the will of God.”

(Chapter 8, On the Primitive Law, pp. 381-382)

In the 『Seomunhaeja』, the character 防 is interpreted as a dike and a character that takes the sound of 方. 方 is a character that means a shape of a corpse hanging on a tree, and 防 is a character that means a place where a person's head is hung and a ritual is performed.

In sacred places, shelves for placing skulls are made to perform magic.

In the 『Shuowen Zhizi』, the word 限 is interpreted as “阻”, and the initial form of 艮 shows the shape of a person turning back under the eyes [目], indicating a limit from which it is difficult to go any further.

The eyes above are probably glancing eyes.

It is a widely practiced method to practice witchcraft by placing a glancing eye on a sacred place.

The reason why sorcerers decorate their eyes is to give them the sorcerous ability to see.

(Chapter 9: Holy Land and Places of Sacrifice, pp. 420-421)

There is a theory that the burning of fields is evidence of slash-and-burn farming, but there is no suitable example in the copy, and the burning of fields seems to mean hunting.

There is a saying in the copy, “burning a beast [bun-geum 焚禽]” (『Eul-pyeon』 205), and in the 『Book of Songs? Jeong-pung』「Dae-suk-woo-jeon 大叔于田」, which is a hunting poem, it sings, “All the flames rise.”

In the Mencius (Deng Wen-gong, Part 1), it is said that “Yik (Inmyeong) thought the mountains and rivers were too lush, so he burned them, and the animals ran away,” which does not refer to slash-and-burn farming.

The word 'geum' means to catch an animal by covering it with a net, and it seems to combine the sound and meaning of 'geum'.

It is thought that the farming technology had already gone beyond the primitive stage, as it was an era in which vast farmland was divided into several sections and managed.

According to the Han Dynasty's "Book of Fan Sheng," when there was a seven-year drought during the reign of King Tang of the Shang Dynasty, Yi Yin created the "division method" (a farming method of dividing the farmland appropriately and planting grains) and taught the people how to divide manure and seeds, and brought water to sprinkle on the crops.

Also, according to the first part of the “Internal Storage” section of the “Han Feizi,” there was a provision in the Yin law that the hand of a person who threw ashes on the road was to be cut off.

There was already a law that used manure or ash as fertilizer.

(Chapter 10 Production and Technology, pp. 470-471)

In the Baekjungsugye, Baek?jung is written as 白?jung in the ?mun.

White is the shape of a skull, and as can be seen from the fact that it is commonly used by the character 伯?패覇, it signifies something important.

The thumb is called 巨擘, and 擘 has the same sound as 白, so Gwak Mal-yak interprets 白 as a pictograph including the shape of the thumbnail, but in that case, he cannot explain the characters of the 拇 system that include the character 白.

The middle one is a flagpole with a flag raised by the general of the central army. When it is a military flag, it has several narrow, long strips attached to the top and bottom so that it flutters in the wind.

The 仲 in 伯仲 means middle.

(Chapter 11, In the World, p. 529)

It was at the end of the Spring and Autumn Period that medicine emerged as a substitute for shamanism.

The era of Bian Guo, who is said to have transmitted the medical techniques of the Yellow Emperor, corresponds roughly to the era of Hippocrates.

Pyeonjak was a man who was called a divine doctor because he treated the elderly and children at the time.

But by this faith, medicine was deviated from God.

Medicine, separated from the gods, could only become a priesthood by swearing to the gods, including Apollo, the god of medicine, that it would be pure and clean, just like the 'oath' that Hippocrates demanded of many medical practitioners.

These two people seemed to have something in common: they both enjoyed life and medicine.

(Chapter 11, In the World, p. 574)

There is a character in the form of the character for prisoner in the sentence, but it is different from the character for prisoner in the sentence for prisoner, which means to catch and put in prison. Looking at the examples, we can see that it is a character that means death.

It probably means putting a person in a coffin.

Traces of multiple burials remain in the ceremonial system, and leaving the body in its original form was considered a basic condition for resurrection.

囚 is the shape of a corpse lying down, and 亡 is the shape of a corpse turned upside down.

In the 『Shuowen Zhaizi』, the word ‘Mang’ is interpreted as ‘to run away’, but it originally means death.

Speaking of "there is hope" in preparation for death also means "there is hope" in preparation for death.

The character for Cheonbu 川部 (heavenly section) is described in the 『Seomunhaeja』 as “the water is wide,” and the sound of this character is the same as 荒 (wild).

? is similar to the character included in the character 流, 流 is a character related to throwing a newborn baby into the water, and ? is in the shape of a dead person, with the lower part being the shape of hair.

A corpse found abandoned in the grass is called a wasteland. This happens when there is a famine or drought.

(Chapter 12, The Thought of Life, pp. 598-599)

Ghosts are feared beings, but some of them are particularly irritating.

For example, Bal-Hwa is a drought ghost.

In the "Great Wild North Classic" of the "Classic of Mountains and Seas," a ghost wearing blue clothes appears on Mount Jigun. This ghost is a female ghost of drought and is called "Yeobal."

When the Yellow Emperor fought against Chiyou, Chiyou led the wind god and the rain god to create wind and rain to resist, so the Yellow Emperor sent Lu Bo, who lived in the sky, to suppress him. However, Lu Bo could not ascend to the sky and stayed on the ground.

It is said that he was bald, 2-3 feet tall, had eyes on the top of his head, and that he could move far like the wind.

It is said that where the yeobal appears, there will be a great drought and the land for a thousand li will turn red.

In relation to this, in the “Benjingxun” of the “Huainanzi,” an encyclopedic work of the Former Han Dynasty, there is a record that says, “In ancient times, when Cangjie created letters, the sky dropped grain and ghosts cried at night.”

"Bon Kyung-hun" assumes that all creations based on human wisdom are a path to losing the innocence of the ancient past, and lists numerous tales about the origin of things, concluding with the words, "Intelligence increases more and more, and virtue decreases more and more."

This is a cultural view of history based on the Taoist philosophy of Lao-Zhuang. The heavens dropping grain signifies an abnormality, and the ghosts crying at night lament the fact that human wisdom has encroached on the power of the gods.

This also means that the naturally occurring spoken language became an artificially created written language, which was able to open up a free human mental world.

The era of ghosts is already over.

(Chapter 1: The Origin of Letters, p. 22)

The foundation for the study of Chinese characters' morphology was laid by Xu Xin's four-volume 『Shuowen Jiezi』 during the Later Han Dynasty.

The Seolmoohaeja is a book that provides a morphological explanation of 9,353 Chinese characters based on the compositional principles of the six Chinese characters.

Although the Six Books were already mentioned in the Hanshu 「Book of Han」「Records of Arts and Literature」 and Jeong Hyeon's commentary on the Zhouli, the Shuowen Jiezi is the first to explain their compositional principles.

The six books are hieroglyphs, instructions, meetings, sounds, introductory notes, and borrowing methods.

It is generally known that the first four types are methods of creating characters, and the last two types are methods of using the created characters, but the six books are all about the principles of character composition.

(Chapter 1: The Origin of Letters, p. 25)

Since the Spring and Autumn Period, names and characters have had related meanings.

The character of the person mentioned above is Yibo, which is related to the custom of the barbarians, tattooing.

Yan Hui, a disciple of Confucius, had the courtesy name Zi Yuan, and Yuan refers to a pond [Huishui].

Zeng Cham's courtesy name is Ziyeo, and his name, which is also read as Sam, is an abbreviated character of Cham [?: meaning to tie three horses to one cart], and both his name and courtesy name are related to carts [車輿].

Sam is the name of a star, so it should be read as Zeng Cham.

It is said that Meng Jia also called Ja Yu.

From this relationship of name and waiting, it is common in an age-based society that one must first have a name, but one is not recognized as a full member of a clan until one becomes an adult.

The name is given at the initiation ceremony to become a clan member, and until then, a baby name is used.

This is called a small letter.

The child is given a gift when performing a ritual to visit the ancestral shrine to report the work of raising the child to the spirit of the ancestors.

The character 字 is a character that represents such a shrine visit.

(Chapter 1: The Origin of Letters, pp. 62-63)

The god of drought is called Yeobal.

In the "Great Wild North Classic" of the "Classic of Mountains and Seas," it is said that in the Ji Kun Mountains of Da Huang, which are very far from China, there is a tower of Gong Gong, and there is a god dressed in blue who is said to be the daughter of the Yellow Emperor.

When Chiyou started a rebellion and led the Earl of Wind and the Master of Rain to attack, the emperor sent Lu Bal down to the earth to pacify the rebellion.

Later, it is said that Yeobal lost his way to heaven and that the place where he was was hit by a drought.

魃 is also written as ? and is the goddess of baldness.

The public domain where Yeobal lived is recorded in the “Overseas Beijing” section of the Shan Hai Jing as being north of Kunlun Mountain, and in ancient times, Sangryu, a subject of Gong Gong who failed to control floods and was killed, had nine human heads and the body of a snake and also lived here.

It is said that at the four corners of the public pavilion there are snakes with tiger stripes, their heads facing south.

This tower probably had a temple-like form similar to a ziggurat.

The god who failed to control the flood and the god of drought, Yeobal, are living together here.

(Chapter 2, The Inseparable Principle, p. 91)

The king also served as a shaman and presided over the ritual.

It was the king's job to judge the signs and determine good or bad fortune.

The king also supervised the ceremonies and offered many sacrifices.

The god that the king worshipped in this way was called the Emperor.

This absolute sovereign god is called Sangje, and in fact, in the copy, he said something like, “Will Sangje send down a drought?”

It was believed that the kings who became the ancestors of a dynasty were called after their deaths and accompanied the Shangdi on the left and right sides. The inscriptions on the bronze statues say, “The former kings solemnly stand on the Shangdi’s left and right sides,” and “The twelve are where the Shangdi is.”

The ancestral god is called the Lower Emperor, and these two are combined to be called the Upper and Lower Emperors.

The Supreme Being exercised complete dominion not only over the natural world but also over all things on earth, and he used the Baeksin gods to exercise this dominion.

The phrase "Emperor Huang and Baek Shin" appears in the Zong Zhou Zhong of the mid-Western Zhou Dynasty.

Even in the heavenly world, there was a strict order.

(Chapter 2, The Inseparable Principle, pp. 96-97)

Since there is no way to express the names of the directions specifically, they were expressed by borrowing sounds or relying on other means.

Dongdong is originally shaped like a pocket.

When the East was used only to mean direction, a separate character called Tak? was created.

The stone in this character is a sound talisman, and has the sound of tapping and tapping.

The shape of the character 東 is that of a tied pocket, that is, a pocket with tied top and bottom entrances.

In the 『Seomunhaeja』, the east is described as the sun [日] hanging in the middle of a tree [木], and the tree is the sacred tree of the east, Fusang [扶桑], and the sun rises from there, so it is interpreted based on the solar legend, but the shape of the old character is not like that.

It can be seen that all characters that include the shape of 東 have the meaning of pocket.

The same goes for the characters of the Bujeon lineage.

Among the characters created by the positions of 木 and 日, ? is “明” in the “Shuowen Haizi”.

It follows the meaning of the sun and is above the tree, and the myo is the shadow.

It is seen as indicating a temporal state by saying, “Following the meaning of the sun and under the tree,” but the structure of the character is completely different from that of the east.

(Chapter 3 Myths and Background, p. 131)

Along with the river, sacrifices to Akak were also popular.

Ak is thought to be the current Songshan Mountain in Hanam, and its old name was Ak.

The evil that stands tall on the plains of Hanam was once considered a sacred place for several clans with the surname Kang and was worshipped as their ancestral god.

In relation to this, in the “Sanggo” section of the “Book of Songs” it is written, “The towering peak is Ak, so high that it reaches the sky.

Evil sent down God and gave birth to Bo and Shin.

“Bo and Shin are the guardians of the Zhou,” he said.

Bo and Shin are considered to be descendants of the god of the mountains, and in addition, Heo and Je of the surname Kang, who later entered Shandong, are said to be the four kingdoms of the surname Kang.

All of these countries were founded by the descendants of evil spirits.

The countries with the surname Kang and the states with the surname Hee have had friendly relations for a long time.

The progenitor of the state is said to be Kang Won, and there is a birth story that he gave birth to Queen Ji by stepping in the footprints of a giant.

Even after entering the Spring and Autumn Period, the two surnames maintained a very close relationship, and in the “Yangzhi Shui” section of the “Book of Songs and the Wind of Kings”, it is recorded that Zhou dispatched troops to the three countries of Shen, Fu, and Xu to defend them against the threat of Chu in the south.

(Chapter 3 Myths and Background, pp. 161-162)

It is easy to see from the shapes of the characters "bang", "gyo", and "bian" that there was a custom in ancient China of offering up severed heads for sacrifice, and many surrounding ethnic groups also had customs of regarding skulls as magical objects.

The Wuhu people, who belonged to the Nanman barbarians, used to store wine in skulls, and Helian Bobo (the name of the king) of Daxia, who was said to be a descendant of the Xiongnu, gathered human heads together to make the arched gates of his military camps [capital gates].

Also, in Taiwan and other southern islands, the custom of making a pedestal [a skeleton-covered platform] or a shelf to place a skull on has long persisted.

Banishment is a ritual of exile, and exile is a spell of change. It was performed not only in the border areas, but also in the capital, sanctuaries, and places of worship.

(Chapter 4: Fear of Two-legged Gods, pp. 190-191)

In sacred buildings, an earth-shaking ritual was performed, and dogs were used as sacrifices.

In the 『Shuowen Zizi』, it is said that “Climbing to a high place”.

It takes the meaning of Gyeong and You.

It is interpreted as taking the sound and meaning of 尤, meaning “something that is especially outstanding compared to the average.”

In the text, 尤 is interpreted as meaning “will there be no disaster [尤]?” and 就 means sacrificing a dog in the Jeonki of Gyeonggwan.

The use of dogs for electricity and as sacrifices in sacred places can be inferred from the many dog sacrifices found in the ruins of Yin tombs and shrines, and can also be confirmed by the inclusion of dog sacrifices in related characters such as 家, chu, gi, hen, yu, etc.

(Chapter 4: Fear of Two-legged Gods, p. 197)

The word "氏" probably refers to a tool used for stabbing and cutting, which was used to cut up sacrifices and use them in rituals. Just as the person who handles sacrifices with a sharp tool at a ancestral shrine is called "jaejae," the word "氏" refers to a person in charge of handling sacrifices and presenting them for rituals.

Or, there may have been an instance where the name 氏 was used when making a blood oath.

That is, when making an oath, one drinks the blood of a sacrificial animal.

The sacred relic was probably placed in a temple.

In the 『Shuowen Zizi』, Gi is described as “the god of the earth.

It is said that “all things are sent out [Je-Chul-Chul]” and the meaning is interpreted by considering 祈 and Je as a combination of rhymes, and in the “Daejong-Baek” of the “Zhouli? Chun-Gwan” it is said to be “Heavenly gods, human ghosts, and earthly indications [Je-Chul-Chul].”

It can be thought that the reason why 祇 means the spirit of the earth is because the clan as a blood relative was connected through the spirit of the earth.

(Chapter 4: Fear of Two-legged Gods, p. 203)

During war, there were times when local music was played to determine God's will.

It was believed that God's will was also revealed in music.

The saying, “The songs of the southern Chu are not strong [南風不競]” seems to have originated from the Zuo Zhuan (18th year of Duke Yang’s reign).

In ancient times, Shi Guang, a musician of the Jin Dynasty, heard that the Chu army was going to attack, so he sang northern and southern songs to tell fortunes, and predicted that the Chu Dynasty would be defeated, saying, “The songs of the Chu Dynasty in the south are not strong and have many dead sounds.”

It may be for this reason that the 8th chapter of 『Sa-gwang』 in the 「Yemunji」 of 『Hanshu』 is placed in 「Bing-eum-yang」 in 「Bing-seo-ryak」.

Divining good or bad fortune by the sound of a song is the same way of thinking as thinking that victory or defeat can be determined by the sound of drums in a war.

(Chapter 5: On War, p. 231)

In the 『Shuowen Zhizi』, the word ‘學’ is written as 斅, and is interpreted as “覺悟이다” meaning ‘to realize’, but adding ‘복?’ here means to teach.

In the 『Shuowen Zhaizi』, 斅 is added to 敎, ? indicates ignorance, and 臼 is called a sound talisman.

The elements of the word ‘교’ (敎) are almost similar to ‘學’ (學), and in the ‘서문해자’ it is said to mean ‘to learn [효效]’ as it is “to learn from below what has been practiced above.”

All of them have ? as their brother and contain the meaning of teaching and admonishing, but 效, like 寅, has the shape of correcting 矢 by using si-ya as its component, and is a different character from 斅?敎.

In the 『Seolmunhaeja』, 效 is interpreted as “sang-i-da” meaning “to resemble” and is interpreted as meaning to reject [bin-cheok? 斥] 寅, which all mean to correct the arrow, and from this, the meaning of law?in-jeong (寅正) was created.

(Chapter 5 On War, p. 251)

In the 『Shuowen Zizi』, when it says about a song, “it is a song”, it means recitation.

In the 『Shuowen Zizi』, the character 欠 is interpreted as “imitating the shape of steam coming out of a person’s stomach,” and is shaped like a yawn. This character is shaped like an open mouth singing, and 歌 can be seen as the shape of singing, and 訶 can be seen as a word referring to lyrics.

In the 『Shuowen Zhizi』, 訶 is interpreted as “getting angry by making a sound like a horn,” but in the Jinwen, 歌 is written as 訶??, and 訶???歌 are all the same characters.

In short, all characters of the 可 series are close in sound and meaning, and are intended to rebuke God and make him grant what he desires.

(Chapter 6 Primitive Religion, p. 295)

The act of dancing in front of a shrine is called Ha-ha, and the song sung during a shrine ceremony is called Song.

In the 『Seomunhaeja』, it is said to be “shaped [mo?]” and is interpreted as a formative character that takes the sound of 公.

There are also letters that sound like 頌, such as 訟, that use 公 as a component, but these are all negative characters, and 公 honors the shrine where ancestors are worshipped.

In the 『Shuowen Zizi』, public is defined as “sharing equally” and the interpretation from the 『Han Feizi』「Five?」that “turning one’s back on private matters is called public.”

It is interpreted as meaning to turn one's back on one's own and eight on one's back, and the shape of the character for the gate and the gate of the gate represent the flat shape in front of the shrine.

It is thought that by the time of Han Feizi, knowledge of such ancient characters had already been lost.

As stated in “Xiao Xing” of “Book of Songs? Xiao Nan”, “From early morning until late at night, they are in the shrine [gong],” it refers to a shrine [gonggung] where ancestral rites are performed all day long.

All litigation within the clan was conducted at this shrine.

In the 『Seomunhaeja』, the word 訟 is defined as “a fight” and is interpreted as a character that takes the sound of public, meaning to swear in front of a shrine and decide the right or wrong.

Songdo means a song sung in front of a shrine.

(Chapter 6 Primitive Religion, pp. 314-315)

Words are a prayer, a vow to oneself, and a pledge to God.

While claiming to be clean and clear, he takes an aggressive stance against the other person.

In comparison, '어어' can be said to be a defensive word.

In the 『Shuowenhaizi』, the word 語 is said to be “론論이다”, in 論 it is said to be “의議이다”, and in 議 it is said to be “語是”, which are circular interpretations of meaning. The first meaning of 語 is in 吾.

That is, 語 is also the reverse sound of 吾.

In the 『Shuowenhaizi』, 吾 is considered a pronoun for self-appointment, as it is said to be “speaking of oneself,” and 五 is interpreted as a sound symbol. However, since there are no characters that are originally pronouns and they are all borrowed characters, 吾 must have had its original meaning.

(Chapter 7: Faith in the Word, p. 325)

In the 『Shuowen Haizi』, poetry is described as “志이다” and is interpreted as taking the sound of a temple.

In the past, it was a consonant that took the sound of 之, but either way, they are all consonants.

In the “Preface” of the “Mao Biography” of the “Book of Songs,” it is said, “Poetry is what one’s will is directed toward.

“What is in the heart becomes wisdom, and when it is expressed in words, it becomes poetry,” he said, adding that poetry is what wisdom is directed towards, that is, it expresses wisdom through song.

Ji is a character that takes the meaning of 之 and 心.

However, this is nothing more than a literal interpretation applied to literary theory, and it is not true that poetry, which expresses one's will in words, has existed since ancient times.

(Chapter 7: Faith in the Word, p. 345)

After King Goujian of Yue destroyed Wu, he became the sole ruler of the south. He lived a life of luxury with the peerless beauty Xi Shi as his wife. His ministers all wore silk and enjoyed a period of prosperity. However, Fan Li, who had helped him achieve his greatness, suddenly left the country.

His thought was that it is easy for people to share suffering, but not easy to share joy.

When he left, he changed his name to Chijapi? and arrived in the northern state of Qi by sea. He devoted himself to increasing his wealth and enjoyed a leisurely life away from politics.

The wealthy man known in the world as Tao Zhu Gong is his successor.

When Fan Li left the country of Yue, he changed his name to Chii Zi Pi, which is reminiscent of Wu Zixu being put into a chii and thrown into the river. Perhaps, when fleeing the country as an exile, it was necessary to take the form of a person abandoned by law.

It signified self-abandonment and was a courtesy when leaving the country.

(Chapter 8, On the Primitive Law, pp. 375-376)

A thief is not a small thief who drools and covets what is in a bowl.

He is a person who rejects the system and has fallen out of clan society.

The ming plate is a vessel that holds the document of oath, and signifies the oath as a member of a clan.

A thief is one who has abandoned the ties of his clan and has left the clan.

According to the shape of the character seen in the stone drum pattern of the Qin Dynasty, two water characters are added to the upper part of the character 盜.

Pouring water on a bowl can be seen as an act of dirtying the bowl.

The word 沓 is created by adding 水 to 曰, which means a document recording an oath between countries.

In the “Tenth Month Friendship” of the Book of Songs, the word “jun-dap” (沓) means a slanderous word.

Pouring water on the vessel used for the oath document or blood oath, thereby desecrating and cursing it, is an act of abandoning the clan bond and insulting the clan spirit.

To dare to do such a thing is theft.

The character 欠, which is included in the characters of 歐?歌 and other characters, means a curse.

Such defectors must be subject to legal sanctions by the divine grace.

That is, one must be “expelled from one’s fellows by the will of God.”

(Chapter 8, On the Primitive Law, pp. 381-382)

In the 『Seomunhaeja』, the character 防 is interpreted as a dike and a character that takes the sound of 方. 方 is a character that means a shape of a corpse hanging on a tree, and 防 is a character that means a place where a person's head is hung and a ritual is performed.

In sacred places, shelves for placing skulls are made to perform magic.

In the 『Shuowen Zhizi』, the word 限 is interpreted as “阻”, and the initial form of 艮 shows the shape of a person turning back under the eyes [目], indicating a limit from which it is difficult to go any further.

The eyes above are probably glancing eyes.

It is a widely practiced method to practice witchcraft by placing a glancing eye on a sacred place.

The reason why sorcerers decorate their eyes is to give them the sorcerous ability to see.

(Chapter 9: Holy Land and Places of Sacrifice, pp. 420-421)

There is a theory that the burning of fields is evidence of slash-and-burn farming, but there is no suitable example in the copy, and the burning of fields seems to mean hunting.

There is a saying in the copy, “burning a beast [bun-geum 焚禽]” (『Eul-pyeon』 205), and in the 『Book of Songs? Jeong-pung』「Dae-suk-woo-jeon 大叔于田」, which is a hunting poem, it sings, “All the flames rise.”

In the Mencius (Deng Wen-gong, Part 1), it is said that “Yik (Inmyeong) thought the mountains and rivers were too lush, so he burned them, and the animals ran away,” which does not refer to slash-and-burn farming.

The word 'geum' means to catch an animal by covering it with a net, and it seems to combine the sound and meaning of 'geum'.

It is thought that the farming technology had already gone beyond the primitive stage, as it was an era in which vast farmland was divided into several sections and managed.

According to the Han Dynasty's "Book of Fan Sheng," when there was a seven-year drought during the reign of King Tang of the Shang Dynasty, Yi Yin created the "division method" (a farming method of dividing the farmland appropriately and planting grains) and taught the people how to divide manure and seeds, and brought water to sprinkle on the crops.

Also, according to the first part of the “Internal Storage” section of the “Han Feizi,” there was a provision in the Yin law that the hand of a person who threw ashes on the road was to be cut off.

There was already a law that used manure or ash as fertilizer.

(Chapter 10 Production and Technology, pp. 470-471)

In the Baekjungsugye, Baek?jung is written as 白?jung in the ?mun.

White is the shape of a skull, and as can be seen from the fact that it is commonly used by the character 伯?패覇, it signifies something important.

The thumb is called 巨擘, and 擘 has the same sound as 白, so Gwak Mal-yak interprets 白 as a pictograph including the shape of the thumbnail, but in that case, he cannot explain the characters of the 拇 system that include the character 白.

The middle one is a flagpole with a flag raised by the general of the central army. When it is a military flag, it has several narrow, long strips attached to the top and bottom so that it flutters in the wind.

The 仲 in 伯仲 means middle.

(Chapter 11, In the World, p. 529)

It was at the end of the Spring and Autumn Period that medicine emerged as a substitute for shamanism.

The era of Bian Guo, who is said to have transmitted the medical techniques of the Yellow Emperor, corresponds roughly to the era of Hippocrates.

Pyeonjak was a man who was called a divine doctor because he treated the elderly and children at the time.

But by this faith, medicine was deviated from God.

Medicine, separated from the gods, could only become a priesthood by swearing to the gods, including Apollo, the god of medicine, that it would be pure and clean, just like the 'oath' that Hippocrates demanded of many medical practitioners.

These two people seemed to have something in common: they both enjoyed life and medicine.

(Chapter 11, In the World, p. 574)

There is a character in the form of the character for prisoner in the sentence, but it is different from the character for prisoner in the sentence for prisoner, which means to catch and put in prison. Looking at the examples, we can see that it is a character that means death.

It probably means putting a person in a coffin.

Traces of multiple burials remain in the ceremonial system, and leaving the body in its original form was considered a basic condition for resurrection.

囚 is the shape of a corpse lying down, and 亡 is the shape of a corpse turned upside down.

In the 『Shuowen Zhaizi』, the word ‘Mang’ is interpreted as ‘to run away’, but it originally means death.

Speaking of "there is hope" in preparation for death also means "there is hope" in preparation for death.

The character for Cheonbu 川部 (heavenly section) is described in the 『Seomunhaeja』 as “the water is wide,” and the sound of this character is the same as 荒 (wild).

? is similar to the character included in the character 流, 流 is a character related to throwing a newborn baby into the water, and ? is in the shape of a dead person, with the lower part being the shape of hair.

A corpse found abandoned in the grass is called a wasteland. This happens when there is a famine or drought.

(Chapter 12, The Thought of Life, pp. 598-599)

Ghosts are feared beings, but some of them are particularly irritating.

For example, Bal-Hwa is a drought ghost.

In the "Great Wild North Classic" of the "Classic of Mountains and Seas," a ghost wearing blue clothes appears on Mount Jigun. This ghost is a female ghost of drought and is called "Yeobal."

When the Yellow Emperor fought against Chiyou, Chiyou led the wind god and the rain god to create wind and rain to resist, so the Yellow Emperor sent Lu Bo, who lived in the sky, to suppress him. However, Lu Bo could not ascend to the sky and stayed on the ground.

It is said that he was bald, 2-3 feet tall, had eyes on the top of his head, and that he could move far like the wind.

It is said that where the yeobal appears, there will be a great drought and the land for a thousand li will turn red.

(Chapter 12, The Thought of Life, p. 611)

Publisher's Review

What was the context in which Chinese characters were born? Using oracle bone script and bronze inscriptions, this study systematically elucidates the meaning of Chinese characters by themes such as "myth," "life," "religion," "production," "war," and "song and dance." This study delves deeply into the thinking of ancient people and explains the process of Chinese character creation, the essence of "Shirakawa Script Studies."

Purpose and Overview of Publication

This book traces back to the origins of Chinese characters, using religiosity and sorcery as keywords.

It reflects the latest archaeological and folkloristic achievements in the traditional Chinese character research system, and crosses the boundaries between Chinese character studies and archaeology.

The invention of writing enabled mankind to develop from a primitive society to a civilized society.

However, the writing that opened up civilization contains a long, primitive world behind it.

Chinese characters, which are pictographic characters, are characters that were established on a long historical foundation before the so-called civilization.

A world from the distant past, now lost through oral tradition or records, casts a deep shadow on Chinese characters.

It may not speak for itself like a fossil, but we can unearth the antiquity that lies behind the ancient writing.

Furthermore, we can also confirm the reality of the society that formed the basis for the creation of ancient letters.

Shirakawa Shizuka (1910-2006) was a world-renowned Japanese scholar of Chinese literature and Chinese characters.

He served as a professor at Ritsumeikan University and continued to engage in active academic activities after retirement until his death in 2006.

The three-volume Chinese character study series, 『字統』, 『字訓』, and 『字通』, are his representative works to which he devoted his life.

His theory, which holds that religious and magical elements played a role in the formation of early Chinese characters such as oracle bone script and bronze script, is called 'Shirakawa Script' and has been highly regarded internationally.

Through the basic work of mapping out tens of thousands of pages of oracle bone data, the original meaning of Chinese characters was systematized into character types, and further, their religious and magical backgrounds were elucidated through character analysis.

Shirakawa was particularly absorbed in the study of oracle bone script and gold inscriptions in order to read ancient literature such as the Book of Songs in the context of the society of the time, and to restore the language used in the society of the time.

He particularly valued the empirical process of thoroughly researching and analyzing the usage of vocabulary, and he personally practiced it.

By doing so, he revealed the errors in the 『Shuowen Zhizi』 written by Xu Shen of the Later Han Dynasty.

Shirakawa used oracle bone script and gold script, which were the early characters of the formation of Chinese characters, as data, and interpreted the characters with the ideas of the era when Chinese characters were formed, but maintained the attitude and methodology of systematically and systematically interpreting Chinese characters based on their character forms.

Shirakawa's academic attitude and methodology are clearly revealed in this book, "The World of Chinese Characters - The Origin of Chinese Culture."

This is a general explanation of the 1,460 Chinese characters that appear in oracle bone script and bronze inscriptions, categorized by problem-history and grouped by type.

And, based on the lifestyle of the time when Chinese characters were created, the entire book is divided into 12 chapters and related characters are interpreted. What runs through the entire book is, above all, the characteristic of religiousness and sorcery.

In the distant past, letters were called 文.

The word "character" first appears in the "Shi Huang Ben Ji" section of "Records of the Grand Historian" written by Sima Qian.

In the 『Spring and Autumn Annals of Zuo』, which records events from the Spring and Autumn Period, there are several cases where names were given to newborns based on palm patterns.

In the 『Seomunhaeja』, the text is “crossed strokes.”

It is said to be “imitating a crossed pattern,” and is interpreted as a character that forms a pattern by crossing lines.

The X shape was considered the basic form of the pattern, and the crossed pattern refers to the X shape at the bottom of the pattern.

However, the 『Shuowenhaizi』 does not say what its upper part is modeled after.

There are many characters in the shape of 文 in the double-sided or gold pattern.

The basic form of 文 is the frontal shape of a person standing, as is known in comparison to 大.

However, the chest area is marked particularly large, and there are variations of these, such as V-shaped, X-shaped, and heart-shaped.

This is clearly a pattern and tattoo added to the chest.

In other words, the character 文 represents a tattoo engraved on the chest, and the original meaning of this character also means tattoo.

China, where the custom of tattooing had long since disappeared, regarded the tattoos that remained among the surrounding peoples as an uncivilized, barbarian custom.

For example, in 『Zuo Zhuan』, 『Chunqiu Quliang Zhuan』, 『Zhuangzi』 「Xiaoyao You」, 『Mozi』 「Confucius and Meng」, etc., there are records that there was a custom of cutting hair and getting tattoos in coastal regions such as Wu and Yue.

Without the custom of tattooing, the character shape representing tattoos would not have been created, and characters such as ?, 産, 彦, 顔, which use 文 as a component of their character shape, and characters such as 凶, 匈, 胸, 爽, 奭, 爾, which represent chest tattoos, would not have been created.

Moreover, 文 not only means tattoos or letters in general, but later became a character that represented the ideology of Chinese culture and signified its traditions.

Confucius's statement, "King Wen has passed away, but isn't his culture still here?" (Analects, "Zi Hui") signifies his awareness of that tradition.

The reason why literature is given such a high ideological meaning is because it originally originated from the ancient concept of sacredness.

In this way, Shirakawa traces the origin of Chinese characters.

Oracle bone inscriptions and bronze inscriptions are the oldest written sources, and therefore, knowledge of ancient characters is necessary to properly understand oracle bone inscriptions and bronze inscriptions.

To study ancient script, knowledge of oracle bone script and bronze inscriptions is necessary.

In that respect, 『The World of Chinese Characters』 is an extension of Shirakawa's previous works, 『The World of Gold Script』 and 『The World of Oracle Bone Script』.

Shirakawa pointed out the educational reality of Chinese characters and classics in Japan, and expressed concern that the declining ability to express and understand Japanese would lead to a decline in the ability to think and create, and even to spiritual devastation.

He also emphasized that culture is supported and developed by writing, and that language can function as culture only through writing.

This book seeks to understand the meaning of the structure of Chinese characters within the intellectual and cultural background of their formation.

“Recovering the world of ancient letters is the task of recovering the world of thought that supported that era, that life, and that life.

There lies the origin of Chinese culture, and also the origin of the East Asian world.

It is no coincidence that Chinese characters were used in East Asia.

The fact that there was basically the same kind of life there made it possible.” Therefore, the study of ancient characters like this will be very useful in thinking about the original nature of our ancient culture, which must have had similar basic experiences.

Purpose and Overview of Publication

This book traces back to the origins of Chinese characters, using religiosity and sorcery as keywords.

It reflects the latest archaeological and folkloristic achievements in the traditional Chinese character research system, and crosses the boundaries between Chinese character studies and archaeology.

The invention of writing enabled mankind to develop from a primitive society to a civilized society.

However, the writing that opened up civilization contains a long, primitive world behind it.

Chinese characters, which are pictographic characters, are characters that were established on a long historical foundation before the so-called civilization.

A world from the distant past, now lost through oral tradition or records, casts a deep shadow on Chinese characters.

It may not speak for itself like a fossil, but we can unearth the antiquity that lies behind the ancient writing.

Furthermore, we can also confirm the reality of the society that formed the basis for the creation of ancient letters.

Shirakawa Shizuka (1910-2006) was a world-renowned Japanese scholar of Chinese literature and Chinese characters.

He served as a professor at Ritsumeikan University and continued to engage in active academic activities after retirement until his death in 2006.

The three-volume Chinese character study series, 『字統』, 『字訓』, and 『字通』, are his representative works to which he devoted his life.

His theory, which holds that religious and magical elements played a role in the formation of early Chinese characters such as oracle bone script and bronze script, is called 'Shirakawa Script' and has been highly regarded internationally.

Through the basic work of mapping out tens of thousands of pages of oracle bone data, the original meaning of Chinese characters was systematized into character types, and further, their religious and magical backgrounds were elucidated through character analysis.

Shirakawa was particularly absorbed in the study of oracle bone script and gold inscriptions in order to read ancient literature such as the Book of Songs in the context of the society of the time, and to restore the language used in the society of the time.

He particularly valued the empirical process of thoroughly researching and analyzing the usage of vocabulary, and he personally practiced it.

By doing so, he revealed the errors in the 『Shuowen Zhizi』 written by Xu Shen of the Later Han Dynasty.

Shirakawa used oracle bone script and gold script, which were the early characters of the formation of Chinese characters, as data, and interpreted the characters with the ideas of the era when Chinese characters were formed, but maintained the attitude and methodology of systematically and systematically interpreting Chinese characters based on their character forms.

Shirakawa's academic attitude and methodology are clearly revealed in this book, "The World of Chinese Characters - The Origin of Chinese Culture."

This is a general explanation of the 1,460 Chinese characters that appear in oracle bone script and bronze inscriptions, categorized by problem-history and grouped by type.

And, based on the lifestyle of the time when Chinese characters were created, the entire book is divided into 12 chapters and related characters are interpreted. What runs through the entire book is, above all, the characteristic of religiousness and sorcery.

In the distant past, letters were called 文.

The word "character" first appears in the "Shi Huang Ben Ji" section of "Records of the Grand Historian" written by Sima Qian.

In the 『Spring and Autumn Annals of Zuo』, which records events from the Spring and Autumn Period, there are several cases where names were given to newborns based on palm patterns.

In the 『Seomunhaeja』, the text is “crossed strokes.”

It is said to be “imitating a crossed pattern,” and is interpreted as a character that forms a pattern by crossing lines.

The X shape was considered the basic form of the pattern, and the crossed pattern refers to the X shape at the bottom of the pattern.

However, the 『Shuowenhaizi』 does not say what its upper part is modeled after.

There are many characters in the shape of 文 in the double-sided or gold pattern.

The basic form of 文 is the frontal shape of a person standing, as is known in comparison to 大.

However, the chest area is marked particularly large, and there are variations of these, such as V-shaped, X-shaped, and heart-shaped.

This is clearly a pattern and tattoo added to the chest.

In other words, the character 文 represents a tattoo engraved on the chest, and the original meaning of this character also means tattoo.

China, where the custom of tattooing had long since disappeared, regarded the tattoos that remained among the surrounding peoples as an uncivilized, barbarian custom.

For example, in 『Zuo Zhuan』, 『Chunqiu Quliang Zhuan』, 『Zhuangzi』 「Xiaoyao You」, 『Mozi』 「Confucius and Meng」, etc., there are records that there was a custom of cutting hair and getting tattoos in coastal regions such as Wu and Yue.

Without the custom of tattooing, the character shape representing tattoos would not have been created, and characters such as ?, 産, 彦, 顔, which use 文 as a component of their character shape, and characters such as 凶, 匈, 胸, 爽, 奭, 爾, which represent chest tattoos, would not have been created.

Moreover, 文 not only means tattoos or letters in general, but later became a character that represented the ideology of Chinese culture and signified its traditions.

Confucius's statement, "King Wen has passed away, but isn't his culture still here?" (Analects, "Zi Hui") signifies his awareness of that tradition.

The reason why literature is given such a high ideological meaning is because it originally originated from the ancient concept of sacredness.

In this way, Shirakawa traces the origin of Chinese characters.

Oracle bone inscriptions and bronze inscriptions are the oldest written sources, and therefore, knowledge of ancient characters is necessary to properly understand oracle bone inscriptions and bronze inscriptions.

To study ancient script, knowledge of oracle bone script and bronze inscriptions is necessary.

In that respect, 『The World of Chinese Characters』 is an extension of Shirakawa's previous works, 『The World of Gold Script』 and 『The World of Oracle Bone Script』.

Shirakawa pointed out the educational reality of Chinese characters and classics in Japan, and expressed concern that the declining ability to express and understand Japanese would lead to a decline in the ability to think and create, and even to spiritual devastation.

He also emphasized that culture is supported and developed by writing, and that language can function as culture only through writing.

This book seeks to understand the meaning of the structure of Chinese characters within the intellectual and cultural background of their formation.

“Recovering the world of ancient letters is the task of recovering the world of thought that supported that era, that life, and that life.

There lies the origin of Chinese culture, and also the origin of the East Asian world.

It is no coincidence that Chinese characters were used in East Asia.

The fact that there was basically the same kind of life there made it possible.” Therefore, the study of ancient characters like this will be very useful in thinking about the original nature of our ancient culture, which must have had similar basic experiences.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: October 29, 2008

- Format: Hardcover book binding method guide

- Page count, weight, size: 659 pages | 1,349g | 153*224*35mm

- ISBN13: 9788981339012

- ISBN10: 8981339015

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)