The Midwifery of Comparison

|

Description

Book Introduction

“I dare say that Eisenstein and Benjamin

Regardless of whether or not there is actual meeting and interaction, what can each person expect?

“He was the best opponent, a special contemporary.”

I have never met you before in my life

Benjamin and Eisenstein.

It was a common interest between the two people

Through the glass house, Mickey Mouse, and Chaplin,

It redraws the historical constellation that formed around them.

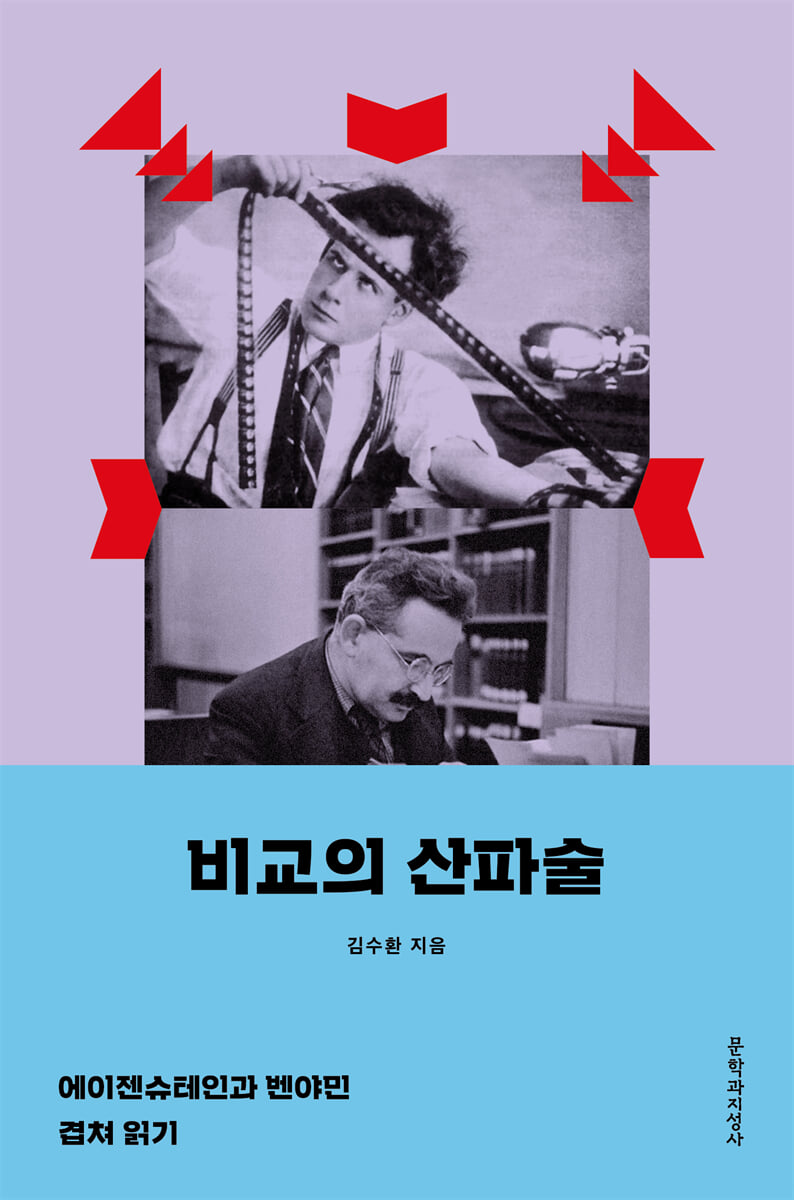

Walter Benjamin (1892-1940) and Sergei Eisenstein (1898-1948), born at the end of the 19th century, developed philosophical thought and artistic experimentation during an era of unprecedented violence and utopian hope.

『The Midwifery of Comparison』, which compares the thoughts and creations of two people, has been published by Munhak-kwa-Jiseong-sa.

Eisenstein and Benjamin shared a number of common concerns and methodologies, starting with the well-known common subject of inquiry, "film," and they also had acquaintances who could serve as a link. However, there is no record of them ever having met or of referencing each other's work during their lifetimes.

This book focuses on three symbols that encapsulate the various issues that captivated the two men: the 'glass house', 'Mickey Mouse (Disney), and 'Charlie Chaplin', and explores the interesting ways in which their trajectories intersect and diverge.

This comparative reading attempted by the author reveals the characteristics and significance of their thoughts and creations more clearly than analyzing each character separately.

As we follow the reflections of the two figures colliding with each other, we encounter their unfamiliar and new faces.

Furthermore, through careful analysis and bold reasoning, we come to understand that this seemingly trivial theme was not merely a peripheral concern of the two men, but rather a connection to the fundamental problems of the 20th century, captured by the radar of two intellects who were more astute than anyone else in the past century, and testified to the existence of deeper and more extensive strata and veins flowing beneath them.

Starting with 『Thinking Structures』, which dealt with Yuri Lotman, the founder of cultural semiotics, and continuing with 『The Ragpicker of the Revolution』, which traces the traces of the Soviet avant-garde engraved in Benjamin's thought through Benjamin's records of his visit to Moscow, this is the fourth book by Professor Kim Soo-hwan, who has steadily expanded his readership by demonstrating a wide academic spectrum and depth beyond the boundaries of academic disciplines.

Regardless of whether or not there is actual meeting and interaction, what can each person expect?

“He was the best opponent, a special contemporary.”

I have never met you before in my life

Benjamin and Eisenstein.

It was a common interest between the two people

Through the glass house, Mickey Mouse, and Chaplin,

It redraws the historical constellation that formed around them.

Walter Benjamin (1892-1940) and Sergei Eisenstein (1898-1948), born at the end of the 19th century, developed philosophical thought and artistic experimentation during an era of unprecedented violence and utopian hope.

『The Midwifery of Comparison』, which compares the thoughts and creations of two people, has been published by Munhak-kwa-Jiseong-sa.

Eisenstein and Benjamin shared a number of common concerns and methodologies, starting with the well-known common subject of inquiry, "film," and they also had acquaintances who could serve as a link. However, there is no record of them ever having met or of referencing each other's work during their lifetimes.

This book focuses on three symbols that encapsulate the various issues that captivated the two men: the 'glass house', 'Mickey Mouse (Disney), and 'Charlie Chaplin', and explores the interesting ways in which their trajectories intersect and diverge.

This comparative reading attempted by the author reveals the characteristics and significance of their thoughts and creations more clearly than analyzing each character separately.

As we follow the reflections of the two figures colliding with each other, we encounter their unfamiliar and new faces.

Furthermore, through careful analysis and bold reasoning, we come to understand that this seemingly trivial theme was not merely a peripheral concern of the two men, but rather a connection to the fundamental problems of the 20th century, captured by the radar of two intellects who were more astute than anyone else in the past century, and testified to the existence of deeper and more extensive strata and veins flowing beneath them.

Starting with 『Thinking Structures』, which dealt with Yuri Lotman, the founder of cultural semiotics, and continuing with 『The Ragpicker of the Revolution』, which traces the traces of the Soviet avant-garde engraved in Benjamin's thought through Benjamin's records of his visit to Moscow, this is the fourth book by Professor Kim Soo-hwan, who has steadily expanded his readership by demonstrating a wide academic spectrum and depth beyond the boundaries of academic disciplines.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

[Introduction] A Contemporary

[Introduction] Eisenstein-Benjamin constellation

Part 1

Chapter 1.

The Cultural Genealogy of Glass Houses

: Film - Literature - Architecture

Chapter 2.

Eisenstein's Disney and Benjamin's Mickey Mouse

: Primordial archetype or posthuman archetype

Chapter 3.

Chaplin Connection

: Soviet Shadows and Signals from Another World

Part 2

Chapter 4.

Revolution and Sound

: Mr. Sound's Bizarre Adventures in the Land of the Bolsheviks

Chapter 5.

Eisenstein's Capital project

: Film essay, film object, film thought

Original source

Search

[Introduction] Eisenstein-Benjamin constellation

Part 1

Chapter 1.

The Cultural Genealogy of Glass Houses

: Film - Literature - Architecture

Chapter 2.

Eisenstein's Disney and Benjamin's Mickey Mouse

: Primordial archetype or posthuman archetype

Chapter 3.

Chaplin Connection

: Soviet Shadows and Signals from Another World

Part 2

Chapter 4.

Revolution and Sound

: Mr. Sound's Bizarre Adventures in the Land of the Bolsheviks

Chapter 5.

Eisenstein's Capital project

: Film essay, film object, film thought

Original source

Search

Into the book

There is one more thing that should be mentioned in this regard.

Benjamin and Eisenstein share a very distinctive way of thinking.

“The construction of history by looking back rather than looking forward,” that is, the tendency to see the present through the past rather than projecting the future based on the present.

As is well known, the task of making possible the emergence of a counter-history by unearthing the 'prime' buried and distorted in conventionally described history forms the core of Benjamin's "dialectical image."

He said that the real challenge lies in the past, not the future, and now he urged us to “turn our backs on the future and turn to the past.”

On the other hand, for Eisenstein, who attempted to expand the problem of film to the fundamental laws of artistic creation or the original structure of human thought (“primitive spirit”), the past was a significant task with historical-philosophical implications.

--- p.14~15

In this essay, he surprisingly characterizes the contemporary situation (after World War I), in which the entire human experience has been impoverished, not as a desperate tragedy, but rather as a positive condition for “starting anew from scratch,” as “a kind of new barbarism.”

It is precisely under these “zero-point conditions” that people who have resolutely rejected the existing “humanistic image of humanity” that has been passed down and have chosen a radical newness as their cause, or, to borrow Benjamin’s memorable expression, “builders who start by turning the table upside down” without regard for others, appear, and Scheerbart is one of them.

According to Benjamin, Scheerbarthian people are representatives of “humanity entmenscht,” that is, of the non-human.

“Because they reject this humanistic principle, this similarity to humans.

--- p.60

What is the true nature of the fearless recklessness, the optimism that sustains this world of destructive freedom? Clearly, understanding this is directly linked to the task of understanding the following key passage from "About Mickey Mouse."

“In these films, humanity prepares itself to outlive civilization.” But before we delve into this, there’s something else to consider first.

The fact is that the dream form called Disney, that special fairytale world, was conceptualized in a very similar way by Eisenstein, Benjamin's contemporary.

--- p.93

The magical allure of Disney characters turns out to lie in their polymorphism and plasticity, their ability to become anything, their form in a state of permanent self-destruction.

And the archetypal image at the genealogical origin of this absolute freedom is the “primordial protoplasm” which, without any particularly fixed form, can “take all the forms of animal life along the evolutionary ladder.”

So how does this freedom compare with the freedom of Benjamin, which we've already explored? How similar and different is Benjamin's destructive freedom, armed with a characteristic recklessness—a freedom that "detonates the hierarchical order of creatures conceived around humans"—from Eisenstein's differential and amorphous plasma freedom?

--- p.101

Eisenstein asserts that his interest in Chaplin lies not in his “direction, methodology, tricks, or humor,” but in his “particular system of thought.”

His interest is in the system of thought that “allows us to perceive phenomena in such a peculiar way and to react to them through equally strange images.”

Eisenstein then puts forward a premise that reminds us of Adorno.

What underlies what is known as “Chaplin’s humor” is not his appearance, but his special way of “perceiving life.”

After discussing the special perceptions of animals, such as rabbits with their eyes at the back and sheep using their eyes separately, Eisenstein poses a crucial question.

“Through whose eyes does Chaplin look at life?

--- p.149

It is precisely with this question that we encounter another line that has been crucially missing from the existing discussion surrounding Capital and the accompanying discussion of October.

That is the route of 'things'.

Those images that lead to the capture of abstract concepts are none other than various 'images of things'.

The film "October," which marks a decisive step toward the future, is, above all, a film of things, a film filled with images of things.

Benjamin and Eisenstein share a very distinctive way of thinking.

“The construction of history by looking back rather than looking forward,” that is, the tendency to see the present through the past rather than projecting the future based on the present.

As is well known, the task of making possible the emergence of a counter-history by unearthing the 'prime' buried and distorted in conventionally described history forms the core of Benjamin's "dialectical image."

He said that the real challenge lies in the past, not the future, and now he urged us to “turn our backs on the future and turn to the past.”

On the other hand, for Eisenstein, who attempted to expand the problem of film to the fundamental laws of artistic creation or the original structure of human thought (“primitive spirit”), the past was a significant task with historical-philosophical implications.

--- p.14~15

In this essay, he surprisingly characterizes the contemporary situation (after World War I), in which the entire human experience has been impoverished, not as a desperate tragedy, but rather as a positive condition for “starting anew from scratch,” as “a kind of new barbarism.”

It is precisely under these “zero-point conditions” that people who have resolutely rejected the existing “humanistic image of humanity” that has been passed down and have chosen a radical newness as their cause, or, to borrow Benjamin’s memorable expression, “builders who start by turning the table upside down” without regard for others, appear, and Scheerbart is one of them.

According to Benjamin, Scheerbarthian people are representatives of “humanity entmenscht,” that is, of the non-human.

“Because they reject this humanistic principle, this similarity to humans.

--- p.60

What is the true nature of the fearless recklessness, the optimism that sustains this world of destructive freedom? Clearly, understanding this is directly linked to the task of understanding the following key passage from "About Mickey Mouse."

“In these films, humanity prepares itself to outlive civilization.” But before we delve into this, there’s something else to consider first.

The fact is that the dream form called Disney, that special fairytale world, was conceptualized in a very similar way by Eisenstein, Benjamin's contemporary.

--- p.93

The magical allure of Disney characters turns out to lie in their polymorphism and plasticity, their ability to become anything, their form in a state of permanent self-destruction.

And the archetypal image at the genealogical origin of this absolute freedom is the “primordial protoplasm” which, without any particularly fixed form, can “take all the forms of animal life along the evolutionary ladder.”

So how does this freedom compare with the freedom of Benjamin, which we've already explored? How similar and different is Benjamin's destructive freedom, armed with a characteristic recklessness—a freedom that "detonates the hierarchical order of creatures conceived around humans"—from Eisenstein's differential and amorphous plasma freedom?

--- p.101

Eisenstein asserts that his interest in Chaplin lies not in his “direction, methodology, tricks, or humor,” but in his “particular system of thought.”

His interest is in the system of thought that “allows us to perceive phenomena in such a peculiar way and to react to them through equally strange images.”

Eisenstein then puts forward a premise that reminds us of Adorno.

What underlies what is known as “Chaplin’s humor” is not his appearance, but his special way of “perceiving life.”

After discussing the special perceptions of animals, such as rabbits with their eyes at the back and sheep using their eyes separately, Eisenstein poses a crucial question.

“Through whose eyes does Chaplin look at life?

--- p.149

It is precisely with this question that we encounter another line that has been crucially missing from the existing discussion surrounding Capital and the accompanying discussion of October.

That is the route of 'things'.

Those images that lead to the capture of abstract concepts are none other than various 'images of things'.

The film "October," which marks a decisive step toward the future, is, above all, a film of things, a film filled with images of things.

--- p.231~32

Publisher's Review

Glass House, Mickey Mouse (Disney), Charlie Chaplin

Part 1 consists of three chapters.

Chapter 1 focuses on the theme of ‘glass house/glass architecture,’ which occupies an important juncture in the evolution of Benjamin and Eisenstein’s thoughts and creations.

The Glass House is one of the most fascinating chapters in 20th-century European intellectual and artistic history.

The cultural myth of the glass house, which began with the 'Crystal Palace' built at the Great Exhibition in London's Hyde Park in 1851, has been transformed in various ways over the past 100 years, crossing over philosophy, ideology, and art, from Russian utopian/dyutopian literature, to German glass architecture represented by Paul Scherbart and Bruno Taut, to the functionalist architecture of the Bauhaus and Le Corbusier.

Through his unfulfilled film project, Glass House, Eisenstein attempted to concretize his imagination of people living in a house made entirely of glass, a world where everything is transparent.

He wanted to produce the film in the United States, and discussions with Paramount were at a fairly concrete level.

In fact, they even decided to build the glass building for the film in a factory in Pittsburgh.

However, for some reason, he was unable to concretize the idea, and the outline kept being revised, which led to endless delays until it eventually remained only a concept on paper.

It is presumed that what Eisenstein first had in mind when he conceived “The Glass House” was the Russian lineage of the glass house.

By delicately interweaving Benjamin's reflections on glass and transparency, the author demonstrates how the myth of the glass house, amidst the catastrophic circumstances of the turn of the century, has served as a powerful narrative that revives a utopian, primordial dream and seeks a blueprint for a new world beyond capitalist modernity and a new humanity to inhabit it.

It also analyzes how the ideals of total universality and transparency intertwined with the nightmare of totalitarian surveillance and spectacle, evolving into a dualistic vision of utopia and dystopia.

Considering the historical and ideological complexities of this glass architecture, particularly its subtle implications within the contemporary Soviet political context, may shed some light on the significance of the Glass House project's failure and Eisenstein's struggles.

Chapter 2 discusses Disney/Mickey Mouse, which both Benjamin and Eisenstein were fascinated by for different reasons.

Beyond being a representative icon of popular culture, Mickey Mouse has established himself as a powerful symbol of 20th-century culture. How did he leave his mark on the thoughts and practices of these two thinkers? It is well known that Eisenstein, while visiting the United States under the pretext of inspecting Western film sound technology, visited the Disney Studios and developed a close relationship with Walt Disney.

Eisenstein's interest in Disney was not limited to sound technology.

To him, Disney's cartoons were nothing less than an epic tale of paradise reclaimed.

Eisenstein captured the 'pre-human state' of being, represented by 'primordial protoplasm' in the polymorphism and plasticity of Mickey Mouse, a form in which he can become anything, a form in a state of permanent self-dissolution.

Meanwhile, for Benjamin, Mickey Mouse was a special symbol that revealed his aspirations for an alternative world linked to technology and the 'new species of humanity' that would live in it.

He read in the character of Mickey Mouse a 'prefiguration of a posthuman future' that would explode the hierarchical order of creatures centered around humans.

Although these two thinkers moved in different directions—the "primitive" and the "future"—their thinking intersects in the way they both question the prevailing conditions of the present.

Chapter 3 explores the intersection of Benjamin and Eisenstein's thinking through Charlie Chaplin.

Chaplin, a representative icon of popular culture in the early to mid-20th century, provided inspiration to the European avant-garde and early Soviet film aesthetics through his unique acting and directing skills.

The author adds the historical context of the "Chaplin cult" phenomenon in the Soviet avant-garde to existing studies that link Chaplin's idiosyncratic gestures to industrialization and mechanization.

After introducing the circumstances in which Benjamin and Adorno clashed head-on over the liberating potential of laughter offered by Chaplin's films, the book illuminates the theme of 'infantile cruelty' that runs from Adorno to Eisenstein.

Through this, we reexamine the significant position of ‘childhood’ in each of their thoughts, highlighting the ‘neurophysiological’ common denominator of children captured by Benjamin and Eisenstein.

Part 2, Chapter 4 deals with the topic of the introduction of sound in Soviet cinema.

The shift to sound is not only explicitly linked to the Soviet modernization project, but is also closely intertwined with other significant transformations, highlighting the profound implications of sound as a transitional symbol of post-revolutionary Soviet society.

Chapter 5 deals with Eisenstein's unprecedented idea to make a film of Marx's Capital, even following the style of James Joyce (Ulysses).

The author suggests that Eisenstein's bold search for a 'film of the future' be read particularly from the perspective of the 'theory of things.'

Midwifery: A Comparative Study of Benjamin and Eisenstein

Benjamin and Eisenstein shared a very distinctive way of thinking.

It was precisely the “way of looking back instead of looking forward,” that is, the tendency to reveal the present through the past rather than projecting the future based on the present.

In order to examine their thinking comparatively, the author introduces a method called ‘comparative midwifery’ inspired by Alexander Kluge.

This is an attempt to 'give birth' to an unexpected new idea by intentionally colliding two ideas, much like midwives in the past used a kind of 'violence (bad force)' to induce spontaneous movement of a fetus in a breech position during childbirth.

This attempt to transcend the limitations of philology offers an opportunity to view them together as the best possible counterparts and special contemporaries each could hope for, regardless of whether they actually met or interacted.

Benjamin once said that a good archaeological report “reports not only the provenance of the objects found, but also the previous strata from which they were discovered.”

“The true legacy of the dead is not the answers or solutions they left behind,” but “the journey of experimentation and reasoning they undertook to come up with them.”

“Not the concept of the result, but the initial problem awareness that was harbored in the process of creating it, the surrounding expectations and concerns, hopes and frustrations, the inevitable giving ups and a certain bet that was held on to despite all that… these are the true legacy that future generations should inherit.” By revisiting the paths taken by these two men, who are considered the greatest intellects of the 20th century, I hope that they will be able to reconstruct the past questions they wrestled with into new questions for thinking about our times.

Part 1 consists of three chapters.

Chapter 1 focuses on the theme of ‘glass house/glass architecture,’ which occupies an important juncture in the evolution of Benjamin and Eisenstein’s thoughts and creations.

The Glass House is one of the most fascinating chapters in 20th-century European intellectual and artistic history.

The cultural myth of the glass house, which began with the 'Crystal Palace' built at the Great Exhibition in London's Hyde Park in 1851, has been transformed in various ways over the past 100 years, crossing over philosophy, ideology, and art, from Russian utopian/dyutopian literature, to German glass architecture represented by Paul Scherbart and Bruno Taut, to the functionalist architecture of the Bauhaus and Le Corbusier.

Through his unfulfilled film project, Glass House, Eisenstein attempted to concretize his imagination of people living in a house made entirely of glass, a world where everything is transparent.

He wanted to produce the film in the United States, and discussions with Paramount were at a fairly concrete level.

In fact, they even decided to build the glass building for the film in a factory in Pittsburgh.

However, for some reason, he was unable to concretize the idea, and the outline kept being revised, which led to endless delays until it eventually remained only a concept on paper.

It is presumed that what Eisenstein first had in mind when he conceived “The Glass House” was the Russian lineage of the glass house.

By delicately interweaving Benjamin's reflections on glass and transparency, the author demonstrates how the myth of the glass house, amidst the catastrophic circumstances of the turn of the century, has served as a powerful narrative that revives a utopian, primordial dream and seeks a blueprint for a new world beyond capitalist modernity and a new humanity to inhabit it.

It also analyzes how the ideals of total universality and transparency intertwined with the nightmare of totalitarian surveillance and spectacle, evolving into a dualistic vision of utopia and dystopia.

Considering the historical and ideological complexities of this glass architecture, particularly its subtle implications within the contemporary Soviet political context, may shed some light on the significance of the Glass House project's failure and Eisenstein's struggles.

Chapter 2 discusses Disney/Mickey Mouse, which both Benjamin and Eisenstein were fascinated by for different reasons.

Beyond being a representative icon of popular culture, Mickey Mouse has established himself as a powerful symbol of 20th-century culture. How did he leave his mark on the thoughts and practices of these two thinkers? It is well known that Eisenstein, while visiting the United States under the pretext of inspecting Western film sound technology, visited the Disney Studios and developed a close relationship with Walt Disney.

Eisenstein's interest in Disney was not limited to sound technology.

To him, Disney's cartoons were nothing less than an epic tale of paradise reclaimed.

Eisenstein captured the 'pre-human state' of being, represented by 'primordial protoplasm' in the polymorphism and plasticity of Mickey Mouse, a form in which he can become anything, a form in a state of permanent self-dissolution.

Meanwhile, for Benjamin, Mickey Mouse was a special symbol that revealed his aspirations for an alternative world linked to technology and the 'new species of humanity' that would live in it.

He read in the character of Mickey Mouse a 'prefiguration of a posthuman future' that would explode the hierarchical order of creatures centered around humans.

Although these two thinkers moved in different directions—the "primitive" and the "future"—their thinking intersects in the way they both question the prevailing conditions of the present.

Chapter 3 explores the intersection of Benjamin and Eisenstein's thinking through Charlie Chaplin.

Chaplin, a representative icon of popular culture in the early to mid-20th century, provided inspiration to the European avant-garde and early Soviet film aesthetics through his unique acting and directing skills.

The author adds the historical context of the "Chaplin cult" phenomenon in the Soviet avant-garde to existing studies that link Chaplin's idiosyncratic gestures to industrialization and mechanization.

After introducing the circumstances in which Benjamin and Adorno clashed head-on over the liberating potential of laughter offered by Chaplin's films, the book illuminates the theme of 'infantile cruelty' that runs from Adorno to Eisenstein.

Through this, we reexamine the significant position of ‘childhood’ in each of their thoughts, highlighting the ‘neurophysiological’ common denominator of children captured by Benjamin and Eisenstein.

Part 2, Chapter 4 deals with the topic of the introduction of sound in Soviet cinema.

The shift to sound is not only explicitly linked to the Soviet modernization project, but is also closely intertwined with other significant transformations, highlighting the profound implications of sound as a transitional symbol of post-revolutionary Soviet society.

Chapter 5 deals with Eisenstein's unprecedented idea to make a film of Marx's Capital, even following the style of James Joyce (Ulysses).

The author suggests that Eisenstein's bold search for a 'film of the future' be read particularly from the perspective of the 'theory of things.'

Midwifery: A Comparative Study of Benjamin and Eisenstein

Benjamin and Eisenstein shared a very distinctive way of thinking.

It was precisely the “way of looking back instead of looking forward,” that is, the tendency to reveal the present through the past rather than projecting the future based on the present.

In order to examine their thinking comparatively, the author introduces a method called ‘comparative midwifery’ inspired by Alexander Kluge.

This is an attempt to 'give birth' to an unexpected new idea by intentionally colliding two ideas, much like midwives in the past used a kind of 'violence (bad force)' to induce spontaneous movement of a fetus in a breech position during childbirth.

This attempt to transcend the limitations of philology offers an opportunity to view them together as the best possible counterparts and special contemporaries each could hope for, regardless of whether they actually met or interacted.

Benjamin once said that a good archaeological report “reports not only the provenance of the objects found, but also the previous strata from which they were discovered.”

“The true legacy of the dead is not the answers or solutions they left behind,” but “the journey of experimentation and reasoning they undertook to come up with them.”

“Not the concept of the result, but the initial problem awareness that was harbored in the process of creating it, the surrounding expectations and concerns, hopes and frustrations, the inevitable giving ups and a certain bet that was held on to despite all that… these are the true legacy that future generations should inherit.” By revisiting the paths taken by these two men, who are considered the greatest intellects of the 20th century, I hope that they will be able to reconstruct the past questions they wrestled with into new questions for thinking about our times.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: July 10, 2025

- Page count, weight, size: 270 pages | 338g | 137*207*15mm

- ISBN13: 9788932044231

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)