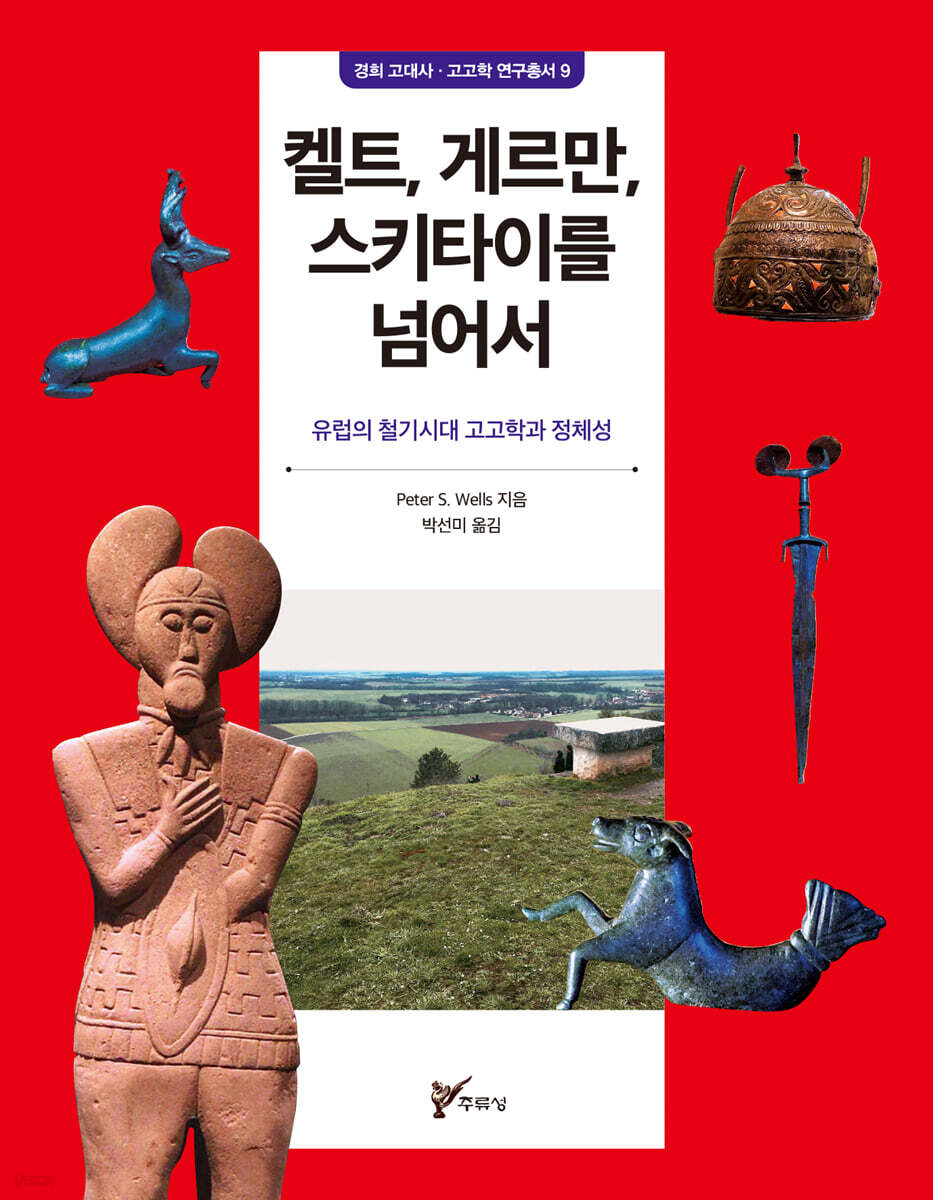

Beyond the Celts, Germans, and Scythians

|

Description

Book Introduction

Comparative analysis of ancient literature and archaeological data,

Exploring the Identity of Ancient European Tribes Through Archaeology

Who created the pottery, bronze and gold jewelry, and ironware archaeologists uncover at excavation sites? Who lived and were buried in the large settlements and tombs built during the Bronze and Iron Ages? Can artifacts and relics reveal the origins of tribes and peoples who left no written records of their history? This is a curiosity shared not only by Koreans but by people around the world when encountering artifacts and relics.

The names we commonly know, such as the Celts, Gauls, and Germans of Europe, the Scythians of Central Asia, and the Dongyi, Yemaek, Donghu, and Xiongnu of Northeast Asia, are names left by others in ancient documents.

So we don't actually know if they called themselves by this name or by something else.

Names such as Celts, Gauls, Germans, and Scythians have come down to us only through Greek and Roman writers.

Author Peter Wells suggests that to understand these peoples who left no written history, we must rely on the archaeological material they created, used, and discarded, rather than relying on outsider records.

As the subtitle, 'Archaeology and Identity in Iron Age Europe' suggests, this book deals with how Iron Age people attempted to express their identity through material objects, and how modern archaeologists can identify the protagonists who left behind these artifacts.

In this process, we are examining the process by which a group develops its identity, Greek and Roman literature, and Iron Age sites from temperate Europe, including France, Germany, Switzerland, and Austria.

To help readers understand the somewhat unfamiliar European archaeological data, the translator has included an introduction introducing sites he personally visited.

Although this book is about Iron Age Europe, the approach and analytical methods used in its research are universal enough to be applied to any period or region worldwide.

I am confident that both beginners in archaeology and general readers will gain a more flexible perspective on the archaeological materials we have left behind today.

Exploring the Identity of Ancient European Tribes Through Archaeology

Who created the pottery, bronze and gold jewelry, and ironware archaeologists uncover at excavation sites? Who lived and were buried in the large settlements and tombs built during the Bronze and Iron Ages? Can artifacts and relics reveal the origins of tribes and peoples who left no written records of their history? This is a curiosity shared not only by Koreans but by people around the world when encountering artifacts and relics.

The names we commonly know, such as the Celts, Gauls, and Germans of Europe, the Scythians of Central Asia, and the Dongyi, Yemaek, Donghu, and Xiongnu of Northeast Asia, are names left by others in ancient documents.

So we don't actually know if they called themselves by this name or by something else.

Names such as Celts, Gauls, Germans, and Scythians have come down to us only through Greek and Roman writers.

Author Peter Wells suggests that to understand these peoples who left no written history, we must rely on the archaeological material they created, used, and discarded, rather than relying on outsider records.

As the subtitle, 'Archaeology and Identity in Iron Age Europe' suggests, this book deals with how Iron Age people attempted to express their identity through material objects, and how modern archaeologists can identify the protagonists who left behind these artifacts.

In this process, we are examining the process by which a group develops its identity, Greek and Roman literature, and Iron Age sites from temperate Europe, including France, Germany, Switzerland, and Austria.

To help readers understand the somewhat unfamiliar European archaeological data, the translator has included an introduction introducing sites he personally visited.

Although this book is about Iron Age Europe, the approach and analytical methods used in its research are universal enough to be applied to any period or region worldwide.

I am confident that both beginners in archaeology and general readers will gain a more flexible perspective on the archaeological materials we have left behind today.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

While publishing the translation

To Korean readers

clear

introduction

Chapter 1.

Archaeology and Identity of the Iron Age

Chapter 2.

Changes in identity in the early Iron Age in Europe

Chapter 3.

Formation of regional identity

Chapter 4.

Description of the typist: First recorded

Chapter 5.

Boundaries and Identity in the Late Iron Age Landscape

Chapter 6.

The Other's Perspective: A Portrayal of the Greeks and Romans

Chapter 7.

Reaction to expression

Chapter 8.

In closing

supplement

bibliographic essay

References

List of maps and drawings

Search

To Korean readers

clear

introduction

Chapter 1.

Archaeology and Identity of the Iron Age

Chapter 2.

Changes in identity in the early Iron Age in Europe

Chapter 3.

Formation of regional identity

Chapter 4.

Description of the typist: First recorded

Chapter 5.

Boundaries and Identity in the Late Iron Age Landscape

Chapter 6.

The Other's Perspective: A Portrayal of the Greeks and Romans

Chapter 7.

Reaction to expression

Chapter 8.

In closing

supplement

bibliographic essay

References

List of maps and drawings

Search

Publisher's Review

Rather than relying on outsider records,

It should be based on the archaeological data they left behind.

As the subtitle, 'Archaeology and Identity in Iron Age Europe' suggests, this book deals with how Iron Age people attempted to express their identity through material objects, and how modern archaeologists can identify the individuals who left behind these artifacts through the study of these artifacts.

In this process, we are examining the process by which a group develops its identity, Iron Age sites in temperate Europe, including France, Germany, Switzerland, and Austria, and Greco-Roman literature that records the tribes that lived there.

Author Peter Wells approaches archaeological material and the identities of its subjects by suggesting new insights for researchers to consider in archaeological sites and artifacts, and considerations for using the literature.

For over a decade, the Korean archaeological community has been producing a lot of research on archaeology and race.

There are many translated works and a considerable amount of research criticizing the problem of nationalist projection in archaeology.

It is a warning against the tendency to associate most archaeological cultures with specific races or groups.

However, it is clear that relics are records reflecting human actions.

Therefore, efforts to understand the protagonists who created, used, and discarded relics must continue.

In this respect, this book strives to show how humanity has attempted to express itself through material, while not forgetting the 'warning', and how material constructs and builds the identity of groups or individuals.

The names of the Celts, Gauls, Germans, and Scythians of Europe, and the Dongyi, Yemaek, Donghu, and Xiongnu of Northeast Asia, were only passed down to us through ancient documents written by others, and we do not know what names they called themselves.

Author Peter Wells emphasizes throughout the book that to understand these people who left no written history, we must rely on the archaeological materials they created, used, and discarded themselves, rather than relying on the records of outsiders.

To help readers understand the somewhat unfamiliar European archaeological data, the translator has included brief notes introducing sites he personally visited.

Although this book is about Iron Age Europe, the approach and analytical methods used in its research are universal enough to be applied to any period or region worldwide.

The translator said, “The process of tracing the background of the first recorded Celts, the errors that are easy to make when dealing with ancient texts, and how the image of the Celts is distorted is reminiscent of the cases of Gojoseon, Buyeo, or Yemaek in early Korean history.

“This book addresses the fundamental issues encountered when dealing with archaeological data, and demonstrates how individuals, societies, and cultures are shaped by so many factors, and how easily images of past inhabitants can be distorted,” he explains.

Author's Note

To Korean readers

We are delighted to announce the Korean translation of Beyond Celts, Germans and Scythians: Archaeology and Identity in Iron Age Europe.

The term "Iron Age" refers to the period from about 800 BC to 50 BC in most of Europe.

In early attempts to understand the Iron Age peoples of Europe, researchers relied heavily on ancient Greek and Roman texts that described them.

Prehistoric societies prior to the Roman conquest, which occurred between the late 2nd century BC and the 1st century BC, left no written records of themselves.

Names such as Celts, Gauls, Germans, and Scythians have come down to us through Greek and Roman writers, and we do not know by what names these peoples called themselves.

My book argues that when studying Iron Age peoples of temperate Europe, we should not rely on outsider accounts, but rather on the archaeological evidence they left behind.

The way they designed personal ornaments, made pottery, constructed tombs, and built settlements can tell us a lot about how they created their identities and how they related to others.

In this book, I have tried to present many archaeological examples that show how Iron Age people understood themselves and their place in the nature and society in which they lived.

Archaeological research in Europe is progressing rapidly, and new discoveries every year provide valuable information about people who lived before written records were created.

Although this book is about Iron Age Europe, the approach and analytical methods used in its research can be applied to any period or region worldwide.

I hope that this book will help Korean readers understand European archaeology and archaeological methodology.

I would like to thank Dr. Park Seon-mi for her interest in my book and for helping to translate it into Korean and prepare it for publication.

It should be based on the archaeological data they left behind.

As the subtitle, 'Archaeology and Identity in Iron Age Europe' suggests, this book deals with how Iron Age people attempted to express their identity through material objects, and how modern archaeologists can identify the individuals who left behind these artifacts through the study of these artifacts.

In this process, we are examining the process by which a group develops its identity, Iron Age sites in temperate Europe, including France, Germany, Switzerland, and Austria, and Greco-Roman literature that records the tribes that lived there.

Author Peter Wells approaches archaeological material and the identities of its subjects by suggesting new insights for researchers to consider in archaeological sites and artifacts, and considerations for using the literature.

For over a decade, the Korean archaeological community has been producing a lot of research on archaeology and race.

There are many translated works and a considerable amount of research criticizing the problem of nationalist projection in archaeology.

It is a warning against the tendency to associate most archaeological cultures with specific races or groups.

However, it is clear that relics are records reflecting human actions.

Therefore, efforts to understand the protagonists who created, used, and discarded relics must continue.

In this respect, this book strives to show how humanity has attempted to express itself through material, while not forgetting the 'warning', and how material constructs and builds the identity of groups or individuals.

The names of the Celts, Gauls, Germans, and Scythians of Europe, and the Dongyi, Yemaek, Donghu, and Xiongnu of Northeast Asia, were only passed down to us through ancient documents written by others, and we do not know what names they called themselves.

Author Peter Wells emphasizes throughout the book that to understand these people who left no written history, we must rely on the archaeological materials they created, used, and discarded themselves, rather than relying on the records of outsiders.

To help readers understand the somewhat unfamiliar European archaeological data, the translator has included brief notes introducing sites he personally visited.

Although this book is about Iron Age Europe, the approach and analytical methods used in its research are universal enough to be applied to any period or region worldwide.

The translator said, “The process of tracing the background of the first recorded Celts, the errors that are easy to make when dealing with ancient texts, and how the image of the Celts is distorted is reminiscent of the cases of Gojoseon, Buyeo, or Yemaek in early Korean history.

“This book addresses the fundamental issues encountered when dealing with archaeological data, and demonstrates how individuals, societies, and cultures are shaped by so many factors, and how easily images of past inhabitants can be distorted,” he explains.

Author's Note

To Korean readers

We are delighted to announce the Korean translation of Beyond Celts, Germans and Scythians: Archaeology and Identity in Iron Age Europe.

The term "Iron Age" refers to the period from about 800 BC to 50 BC in most of Europe.

In early attempts to understand the Iron Age peoples of Europe, researchers relied heavily on ancient Greek and Roman texts that described them.

Prehistoric societies prior to the Roman conquest, which occurred between the late 2nd century BC and the 1st century BC, left no written records of themselves.

Names such as Celts, Gauls, Germans, and Scythians have come down to us through Greek and Roman writers, and we do not know by what names these peoples called themselves.

My book argues that when studying Iron Age peoples of temperate Europe, we should not rely on outsider accounts, but rather on the archaeological evidence they left behind.

The way they designed personal ornaments, made pottery, constructed tombs, and built settlements can tell us a lot about how they created their identities and how they related to others.

In this book, I have tried to present many archaeological examples that show how Iron Age people understood themselves and their place in the nature and society in which they lived.

Archaeological research in Europe is progressing rapidly, and new discoveries every year provide valuable information about people who lived before written records were created.

Although this book is about Iron Age Europe, the approach and analytical methods used in its research can be applied to any period or region worldwide.

I hope that this book will help Korean readers understand European archaeology and archaeological methodology.

I would like to thank Dr. Park Seon-mi for her interest in my book and for helping to translate it into Korean and prepare it for publication.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: June 23, 2025

- Page count, weight, size: 252 pages | 182*257*20mm

- ISBN13: 9788962465570

- ISBN10: 8962465574

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)