Culture of War

|

Description

Book Introduction

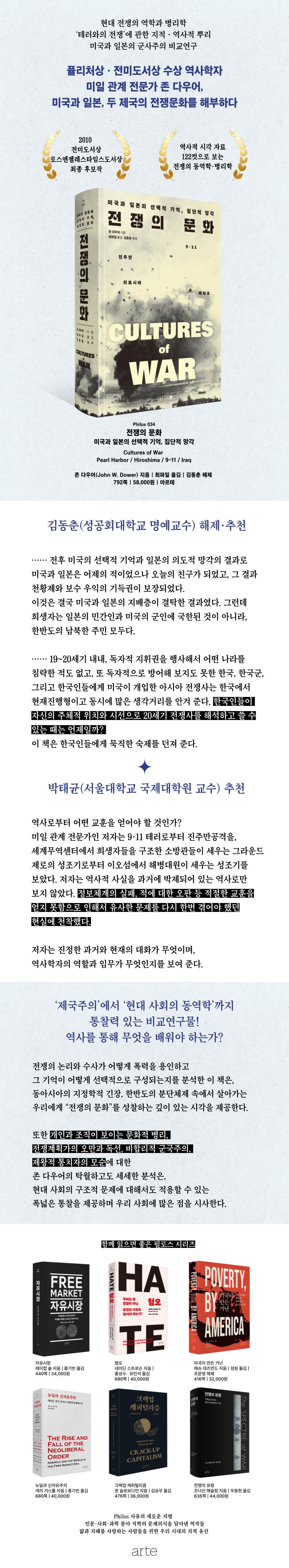

Pulitzer Prize and National Book Award-winning historian

John Dower, an expert on US-Japan relations,

Dissecting the War Cultures of the US and Japan

The Dynamics and Pathology of Modern Warfare

The Intellectual and Historical Roots of the 'War on Terror'

A Comparative Study of American and Japanese Militarism

*2010 National Book Award and Los Angeles Times Book Award finalist

*The Culture of War Through 122 Historical Visuals

John Dower, a prominent American historian, has been examining the origins and consequences of war from various perspectives for several decades.

In 『War without Mercy』(1986), which won the National Book Critics Circle Award (Nonfiction), the brutality and inhumanity of the Pacific War were analyzed in detail.

Embracing Defeat (1999), which won numerous honors including the Pulitzer Prize (Non-Fiction), the National Book Award (Non-Fiction), and the Fairbanks Award (Asian History), is a historical-sociological reconstruction of the struggles that defeated Japan went through to start anew in the land that was reduced to ruins under the occupation of the Allied Forces led by the United States immediately after the Pacific War.

John Dower, an expert on US-Japan relations,

Dissecting the War Cultures of the US and Japan

The Dynamics and Pathology of Modern Warfare

The Intellectual and Historical Roots of the 'War on Terror'

A Comparative Study of American and Japanese Militarism

*2010 National Book Award and Los Angeles Times Book Award finalist

*The Culture of War Through 122 Historical Visuals

John Dower, a prominent American historian, has been examining the origins and consequences of war from various perspectives for several decades.

In 『War without Mercy』(1986), which won the National Book Critics Circle Award (Nonfiction), the brutality and inhumanity of the Pacific War were analyzed in detail.

Embracing Defeat (1999), which won numerous honors including the Pulitzer Prize (Non-Fiction), the National Book Award (Non-Fiction), and the Fairbanks Award (Asian History), is a historical-sociological reconstruction of the struggles that defeated Japan went through to start anew in the land that was reduced to ruins under the occupation of the Allied Forces led by the United States immediately after the Pacific War.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

"The Culture of War": A Look at US-Japan Relations and the Challenges of the Korean Peninsula (Kim Dong-chun)

The Evolution of Preface Exploration

Part 1

“Pearl Harbor” as a code

― Chosen war and intelligence failure

Chapter 1: Disgrace and the Cracked Mirror of History

“Pearl Harbor” as a code

The boomerang of “Pearl Harbor”

Chapter 2 Information Failure

Prelude to Pearl Harbor

Prelude to 9/11

Postmortem: Pearl Harbor

Postmortem: September 11

Chapter 3: Failure of Imagination

“Little yellow bastards”

Rationality, urgency, and risk

Aiding the enemy

“These petty terrorists from Afghanistan”

Chapter 4: Innocence, Evil, and Amnesia

The transition between catastrophe and innocence

The transference of evil and evil

Amnesia and Frankenstein's Monster

An evil worth paying for

Chapter 5: Wars of Choice and Strategic Folly

Pearl Harbor and Operation Iraqi Freedom

Emperor and Imperial Presidency

Choosing War

strategic stupidity

Deception and Delusion

Victory Soldiers and the Gates of Hell

Chapter 6: "Pearl Harbor" as a Thousand-Year-Old

Part 2

Ground Zero in 1945 and Ground Zero in 2001

― Terrorism and mass murder

Chapter 7: "Hiroshima" as Code

Chapter 8: Air Combat and Terrorist Bombing in World War II

ghost towns

Eliminate “non-combatants”

“Increased terrorism” in Germany

Targeting Japan

Firebombing of major cities

“Burning” and “Secondary Targets”

Fraud, shock, psychological warfare

Chapter 9: "The Most Terrifying Bomb in World History"

Ground Zero, 1945

Expect zero

Become death

Ending the war and saving American lives

Chapter 10: The Irresistible Logic of Mass Murder

force

August 1945 and the Rejected Alternatives

unconditional surrender

Power Politics and the Cold War

partisan politics

Chapter 11: Sweetness, Beauty, and Idealistic Extinction

Scientific sweetness and technical demands

Technocratic Momentum and the War Machine

The aesthetics of mass murder

plural

Idealistic Extinction

Chapter 12: New Evils in the World: 1945/2001

irreversible evil

claim to be a god

Holy War Against the West: Seysen and Jihad

Ground Zeroes: State and Non-State Terrorism

Managing savagery

Part 3

War and occupation

― To gain peace, to lose peace

Chapter 13: Occupied Japan and Occupied Iraq

Win the war and lose the peace

Occupied Japan and Glasses in My Eyes

Worlds without common denominators

Planning for postwar Japan

Eyes Closed Tightly: The Occupation of Iraq

Refusal to build a nation

Baghdad is burning

Chapter 14: A Kind of Convergence: Law, Justice, and Violation

Unfair interference with the law

Legal and illegal occupation

War crimes and the backlash of victor's justice

The limbo of the sphere of influence and the defeated army

Wasting intangible assets

Chapter 15: Nation Building and Market Fundamentalism

Control and Capitalism

corruption and crime

Successful and disastrous demilitarization

“General Administrator” vs. “Regional Expert”

Privatization of state-run construction

Making Iraq "Open for Business"

The origin of two eras

A battle from an earlier era to prevent speculation

Conflicting Legacies in an Age of Oblivion

Epilogue: Wasted Effort and Bright Apricots

Secular priests and faith-based policies

mockery

Bright apricot

annotation

Acknowledgements

List of illustrations

Search

The Evolution of Preface Exploration

Part 1

“Pearl Harbor” as a code

― Chosen war and intelligence failure

Chapter 1: Disgrace and the Cracked Mirror of History

“Pearl Harbor” as a code

The boomerang of “Pearl Harbor”

Chapter 2 Information Failure

Prelude to Pearl Harbor

Prelude to 9/11

Postmortem: Pearl Harbor

Postmortem: September 11

Chapter 3: Failure of Imagination

“Little yellow bastards”

Rationality, urgency, and risk

Aiding the enemy

“These petty terrorists from Afghanistan”

Chapter 4: Innocence, Evil, and Amnesia

The transition between catastrophe and innocence

The transference of evil and evil

Amnesia and Frankenstein's Monster

An evil worth paying for

Chapter 5: Wars of Choice and Strategic Folly

Pearl Harbor and Operation Iraqi Freedom

Emperor and Imperial Presidency

Choosing War

strategic stupidity

Deception and Delusion

Victory Soldiers and the Gates of Hell

Chapter 6: "Pearl Harbor" as a Thousand-Year-Old

Part 2

Ground Zero in 1945 and Ground Zero in 2001

― Terrorism and mass murder

Chapter 7: "Hiroshima" as Code

Chapter 8: Air Combat and Terrorist Bombing in World War II

ghost towns

Eliminate “non-combatants”

“Increased terrorism” in Germany

Targeting Japan

Firebombing of major cities

“Burning” and “Secondary Targets”

Fraud, shock, psychological warfare

Chapter 9: "The Most Terrifying Bomb in World History"

Ground Zero, 1945

Expect zero

Become death

Ending the war and saving American lives

Chapter 10: The Irresistible Logic of Mass Murder

force

August 1945 and the Rejected Alternatives

unconditional surrender

Power Politics and the Cold War

partisan politics

Chapter 11: Sweetness, Beauty, and Idealistic Extinction

Scientific sweetness and technical demands

Technocratic Momentum and the War Machine

The aesthetics of mass murder

plural

Idealistic Extinction

Chapter 12: New Evils in the World: 1945/2001

irreversible evil

claim to be a god

Holy War Against the West: Seysen and Jihad

Ground Zeroes: State and Non-State Terrorism

Managing savagery

Part 3

War and occupation

― To gain peace, to lose peace

Chapter 13: Occupied Japan and Occupied Iraq

Win the war and lose the peace

Occupied Japan and Glasses in My Eyes

Worlds without common denominators

Planning for postwar Japan

Eyes Closed Tightly: The Occupation of Iraq

Refusal to build a nation

Baghdad is burning

Chapter 14: A Kind of Convergence: Law, Justice, and Violation

Unfair interference with the law

Legal and illegal occupation

War crimes and the backlash of victor's justice

The limbo of the sphere of influence and the defeated army

Wasting intangible assets

Chapter 15: Nation Building and Market Fundamentalism

Control and Capitalism

corruption and crime

Successful and disastrous demilitarization

“General Administrator” vs. “Regional Expert”

Privatization of state-run construction

Making Iraq "Open for Business"

The origin of two eras

A battle from an earlier era to prevent speculation

Conflicting Legacies in an Age of Oblivion

Epilogue: Wasted Effort and Bright Apricots

Secular priests and faith-based policies

mockery

Bright apricot

annotation

Acknowledgements

List of illustrations

Search

Detailed image

Into the book

Because “Pearl Harbor” is also, as it turns out, a code for other things—for example, the myth of American innocence, victimization, and “exceptionalism,” along with a failure of imagination and common sense.

Biases and preconceptions distort our assessment of the intentions and capabilities of potential adversaries more than those who focus on structural failures usually acknowledge.

This is especially true when differences in race, culture, and religion come into play.

Moreover, such biases hinder our understanding of the grievances of our adversaries.

Even though they appeal to such complaints to mobilize support.

--- p.67

Turned around, this stereotype of the irrational Oriental reflects the persistent assumption that Enlightenment ideals of reason, order, and civilized behavior actually drive modern Western thinking and behavior.

Westerners sometimes think and act rationally.

But this is often not the case, and nowhere is this more evident than in the history of modern war and peace.

Moral issues aside, it's not uncommon for sophisticated scientific and technocratic thinking to run parallel to the wishful thinking, delusions, and reckless behavior of those in power.

--- p.73

Turf wars, “telecommunications,” compulsive secrecy, and simple personal arrogance and irresponsibility were part of the problem, but not the most important part.

The 2003 intelligence disaster, which, instead of liberating Iraq as it had on September 11 and December 7, ultimately tore it apart, also reflected a colossal failure of imagination, a failure that, rather than diminishing, widened in the months following September 11.

--- p.100

The diagnostic language of postmortems on failures of imagination is the same language analysts used long ago to describe the incredulous reactions of those confronted with Pearl Harbor: psychological inadequacies, biases and preconceptions, and serious underestimations of the enemy's intentions and capabilities.

It feels like looking at a pathologist's file of diagnoses, describing almost identical symptoms and repeating the same things.

So, to borrow Roberta Wollstadter's phrase, before September 11, American analysts and (with some marginal exceptions) policymakers simply failed to “anticipate the boldness and creativity of their adversaries.”

--- p.123

While religious tracts defended the conquest of the Philippines as a “just war,” Secretary of War Elihu Root described in more secular terms the establishment of a colonial administration that would promote “happiness, peace, and prosperity.”

He said the Philippines would become a “showcase of democracy.”

These are George W.

They were the ghosts behind Bush's ghostwriters.

There was little truly new in the verbal feast unleashed by the president's scribes and supporters during the run-up to the invasion of Iraq and in the years since.

“Benevolent global hegemony” has replaced “benevolent fairy tale.”

Patriarchal rhetoric like “the white man’s burden” has become simply America’s “burden” without the overt racism.

The “empire” became a “light empire,” but America’s unique sense of goodness, mission, and manifest destiny remained.

--- p.150

Pearl Harbor became a code, a symbol, or a metaphor for the Big War.

This is the worldview that the standard military histories written in the 1970s called “the strategy of annihilation,” which became “the characteristically American way of war” long before World War II.

It's the thinking that made Rumsfeld's immediate reaction to 9/11 ("Let's go big—let's clean it up—all the relevant and all the irrelevant") seem perfectly natural.

But a major war was not required to combat terrorism or insurgency.

--- p.239

Since September 11, this history of World War II has gradually faded from consciousness.

Ground Zero has become a code word for America, a victim of evil forces—namely, alien peoples and cultures who, “unlike us,” do not recognize the sanctity of human life and do not hesitate to murder innocent civilians, men, women, and children.

Such Islamist barbarism is presented as the clearest example of the profound difference between Western and non-Western values, and as evidence of the supposed clash of civilizations.

It would be no exaggeration to say that “Ground Zero 2001” took its name from the past and simultaneously became a wall that blocked all views from reaching the place and object from which its name originated.

--- p.256

In mid-May, two months before the new bomb was ready for testing, J.

Robert Oppenheimer (J.

Robert Oppenheimer) addressed the special dangers faced only by bomber crews from a different perspective.

Oppenheimer's presentation to military planners "regarding the radiological effects of The Gadget" is summarized in the minutes:

“(1) For radiological reasons, no aircraft should be closer than 2½ miles [4 kilometers] to the point of detonation (the distance should be greater for reasons of blast airflow); and (2) aircraft should avoid the cloud of radioactive material.” (“Device” was a widely used code name for the prototype bomb.) Later, on another occasion, Oppenheimer informed the ad hoc committee that radioactivity would be dangerous “within a radius of at least two-thirds of a mile [1.07 kilometers].”

--- p.312

“It is impossible to be a scientist unless you believe that knowledge of the world and the powers that knowledge imparts are in themselves valuable to humanity, unless you believe that you are using those powers to help spread knowledge and are willing to accept the consequences.” This was lofty rhetoric, and the flip side of Oppenheimer’s more chilling reflections on “death, the destroyer.”

--- p.378

The mega-machine, which transcends the individual, also evokes a literal distancing or abstraction that is particularly evident in modern high-tech warfare.

That the vast majority of soldiers in World War II never actually met the enemy face to face; that bombers flew very high over their targets (perhaps a kilometer or more even in so-called low-altitude raids) when they dropped explosives and incendiary bombs; that reliance on aerial reconnaissance photographs to identify areas of “square miles of destruction” helped to sterilize the true horrors of urban bombing; that the planners in Washington and the bomb makers at Los Alamos, Chicago, Oak Ridge, and Hanford were thousands of miles away from “human horror, suffering, and death.”

Distancing has also come to mean metaphorically, that is, isolation and alienation in the big picture, the subordination and self-absorption of individuals and small groups, leading to the abandonment of personal autonomy in an institutional climate that is hostile to questioning and absolutely intolerant of dissent.

--- p.384

Modern warfare is still largely mass killing.

Bureaucracies are collections of powers that fight for territory.

Political morality is often an oxymoron.

And as the final months of the Bush administration revealed, “market-rational” capitalism is largely a myth.

Beliefs and practices unrelated to traditional religions dominate our time, preached and enforced by secular priests.

Biases and preconceptions distort our assessment of the intentions and capabilities of potential adversaries more than those who focus on structural failures usually acknowledge.

This is especially true when differences in race, culture, and religion come into play.

Moreover, such biases hinder our understanding of the grievances of our adversaries.

Even though they appeal to such complaints to mobilize support.

--- p.67

Turned around, this stereotype of the irrational Oriental reflects the persistent assumption that Enlightenment ideals of reason, order, and civilized behavior actually drive modern Western thinking and behavior.

Westerners sometimes think and act rationally.

But this is often not the case, and nowhere is this more evident than in the history of modern war and peace.

Moral issues aside, it's not uncommon for sophisticated scientific and technocratic thinking to run parallel to the wishful thinking, delusions, and reckless behavior of those in power.

--- p.73

Turf wars, “telecommunications,” compulsive secrecy, and simple personal arrogance and irresponsibility were part of the problem, but not the most important part.

The 2003 intelligence disaster, which, instead of liberating Iraq as it had on September 11 and December 7, ultimately tore it apart, also reflected a colossal failure of imagination, a failure that, rather than diminishing, widened in the months following September 11.

--- p.100

The diagnostic language of postmortems on failures of imagination is the same language analysts used long ago to describe the incredulous reactions of those confronted with Pearl Harbor: psychological inadequacies, biases and preconceptions, and serious underestimations of the enemy's intentions and capabilities.

It feels like looking at a pathologist's file of diagnoses, describing almost identical symptoms and repeating the same things.

So, to borrow Roberta Wollstadter's phrase, before September 11, American analysts and (with some marginal exceptions) policymakers simply failed to “anticipate the boldness and creativity of their adversaries.”

--- p.123

While religious tracts defended the conquest of the Philippines as a “just war,” Secretary of War Elihu Root described in more secular terms the establishment of a colonial administration that would promote “happiness, peace, and prosperity.”

He said the Philippines would become a “showcase of democracy.”

These are George W.

They were the ghosts behind Bush's ghostwriters.

There was little truly new in the verbal feast unleashed by the president's scribes and supporters during the run-up to the invasion of Iraq and in the years since.

“Benevolent global hegemony” has replaced “benevolent fairy tale.”

Patriarchal rhetoric like “the white man’s burden” has become simply America’s “burden” without the overt racism.

The “empire” became a “light empire,” but America’s unique sense of goodness, mission, and manifest destiny remained.

--- p.150

Pearl Harbor became a code, a symbol, or a metaphor for the Big War.

This is the worldview that the standard military histories written in the 1970s called “the strategy of annihilation,” which became “the characteristically American way of war” long before World War II.

It's the thinking that made Rumsfeld's immediate reaction to 9/11 ("Let's go big—let's clean it up—all the relevant and all the irrelevant") seem perfectly natural.

But a major war was not required to combat terrorism or insurgency.

--- p.239

Since September 11, this history of World War II has gradually faded from consciousness.

Ground Zero has become a code word for America, a victim of evil forces—namely, alien peoples and cultures who, “unlike us,” do not recognize the sanctity of human life and do not hesitate to murder innocent civilians, men, women, and children.

Such Islamist barbarism is presented as the clearest example of the profound difference between Western and non-Western values, and as evidence of the supposed clash of civilizations.

It would be no exaggeration to say that “Ground Zero 2001” took its name from the past and simultaneously became a wall that blocked all views from reaching the place and object from which its name originated.

--- p.256

In mid-May, two months before the new bomb was ready for testing, J.

Robert Oppenheimer (J.

Robert Oppenheimer) addressed the special dangers faced only by bomber crews from a different perspective.

Oppenheimer's presentation to military planners "regarding the radiological effects of The Gadget" is summarized in the minutes:

“(1) For radiological reasons, no aircraft should be closer than 2½ miles [4 kilometers] to the point of detonation (the distance should be greater for reasons of blast airflow); and (2) aircraft should avoid the cloud of radioactive material.” (“Device” was a widely used code name for the prototype bomb.) Later, on another occasion, Oppenheimer informed the ad hoc committee that radioactivity would be dangerous “within a radius of at least two-thirds of a mile [1.07 kilometers].”

--- p.312

“It is impossible to be a scientist unless you believe that knowledge of the world and the powers that knowledge imparts are in themselves valuable to humanity, unless you believe that you are using those powers to help spread knowledge and are willing to accept the consequences.” This was lofty rhetoric, and the flip side of Oppenheimer’s more chilling reflections on “death, the destroyer.”

--- p.378

The mega-machine, which transcends the individual, also evokes a literal distancing or abstraction that is particularly evident in modern high-tech warfare.

That the vast majority of soldiers in World War II never actually met the enemy face to face; that bombers flew very high over their targets (perhaps a kilometer or more even in so-called low-altitude raids) when they dropped explosives and incendiary bombs; that reliance on aerial reconnaissance photographs to identify areas of “square miles of destruction” helped to sterilize the true horrors of urban bombing; that the planners in Washington and the bomb makers at Los Alamos, Chicago, Oak Ridge, and Hanford were thousands of miles away from “human horror, suffering, and death.”

Distancing has also come to mean metaphorically, that is, isolation and alienation in the big picture, the subordination and self-absorption of individuals and small groups, leading to the abandonment of personal autonomy in an institutional climate that is hostile to questioning and absolutely intolerant of dissent.

--- p.384

Modern warfare is still largely mass killing.

Bureaucracies are collections of powers that fight for territory.

Political morality is often an oxymoron.

And as the final months of the Bush administration revealed, “market-rational” capitalism is largely a myth.

Beliefs and practices unrelated to traditional religions dominate our time, preached and enforced by secular priests.

--- p.611

Publisher's Review

Pulitzer Prize and National Book Award-winning historian

John Dower, an expert on US-Japan relations,

Dissecting the War Cultures of the US and Japan

The Dynamics and Pathology of Modern Warfare

The Intellectual and Historical Roots of the 'War on Terror'

A Comparative Study of American and Japanese Militarism

*2010 National Book Award and Los Angeles Times Book Award finalist

*The Culture of War Through 122 Historical Visuals

Now turning to a larger canvas, John Dower presents Cultures of War: Pearl Harbor/Hiroshima/9-11/Iraq (Philos Series No. 34), a comparative study of an ambitious research project on the dynamics and pathologies of modern warfare.

This book analyzes the cultural patterns of modern war by examining the culture of war revealed through four events: the attack on Pearl Harbor, the bombing of Hiroshima, the 9/11 attacks, and the invasion of Iraq under the pretext of the war on terror.

The issues and topics the author examines as “culture of war” are as follows.

Failures of information and imagination, selective memory and collective forgetting, “strategic imbecility,” secular thinking based on military and religious beliefs, the contradiction between democracy and the imperial presidency (“unitary executive power”), the increasingly blatant rhetoric of holy war, and the targeting of non-combatants (an undeniable logic of mass murder).

John Dower's The Culture of War focuses on the arrogance and hypocrisy of war planners, comprehensively examining how the exercise of seemingly "rational choice" actually leads to symbols of irrationality and irresponsibility, and reveals how the culture of war is formed and sustained.

In the end, it suggests the possibility of “shared cultures of peace and reconciliation” and seeks hope for transcending the culture of war.

The author offers this as a reflection that goes beyond the behavior and pathology of individuals and institutions.

“I want to deal with evil seriously.

Double standards and hypocrisy are other recurring themes, as is the powerful role of memory and grief.

Tragedy is not a popular concept in social science because it is not easily modeled (like ambivalent ambiguity and irrationality).

I started out in the humanities and ended up majoring in history, and for me, tragedy, like evil, seems essential to understanding our war culture.

The use and misuse of history, and its literal disregard, has become another subtext.” ― From the introduction, “The Evolution of Inquiry” (pp. 45-46)

Pearl Harbor, Hiroshima, 9/11, Iraq

A monumental analysis that spans four wars.

“How is violence and aggression justified?”

· The selective memory and intentional forgetting caused by the collusion of the American and Japanese ruling classes have resulted in the sacrifices of both the North and South Korean people on the Korean Peninsula.

Kim Dong-chun, Professor Emeritus, Sungkonghoe University

From the Pearl Harbor attack to the 9/11 terrorist attacks, the author views the past not as mere historical facts, but as a dialogue with the present.

― Park Tae-gyun, Professor, Graduate School of International Studies, Seoul National University

· Drawing on a lifetime of reflection and academic achievement, this book sharply illuminates the wishful thinking, arrogance, and delusion that characterize modern warfare! ― National Book Award Nominee Summary

"The Culture of War" is a significant study that examines the origins of the imperialist logic of modernization and civilization, focusing on the institutional, intellectual, and psychological pathologies of modern war, and how violence and aggression are justified, along with 122 historical visuals.

This book is largely divided into three parts.

Each part reveals the structure of modern warfare, beginning with the tragedy of preemptive strikes brought about by intelligence failures and self-deception (Part 1) and tracing the shadow of mass murder that leads to terrorism and retaliation (Part 2).

Furthermore, it illuminates the paradox of democracy revealed in the process of occupation rule (Part 3) and analyzes how these three aspects form a vicious cycle of imperialist violence.

In addition to this organic analysis, what the author weaves together is “language.”

John Dower analyzes how the rhetoric of war becomes a trap that advocates violence, while simultaneously capturing the paradox that the very language of “peace, freedom, and justice” becomes a tool for waging war regardless of camp.

This goes beyond cynical propaganda; it exposes the essential contradictions of modern warfare through the way in which the culture of war appropriates the language of peace.

Dissecting the Arrogance and Oblivion of Imperialism

Part 1, "Pearl Harbor as Code? Chosen Wars and Intelligence Failures," analyzes the similarities between the intelligence failures and surprise attacks experienced by the United States in 1941 and 2001.

The author points out that such catastrophic events can be a gift to those in power, and compares the crisis responses of the Franklin Roosevelt and Bush administrations.

In particular, he notes the similarities in the “strategic stupidity” of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941 and the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003, noting that while both sides were tactically brilliant, they seriously misjudged the enemy’s psychology and capabilities.

This analysis extends to the Bush administration's "Bush Doctrine" of preemptive strikes in 2003, revealing the tragic pattern of "wars of one's own choosing" demonstrated by Japan in 1941, al-Qaeda in 2001, and the United States in 2003.

Part 2 covers "Ground Zero 1945 and Ground Zero 2001: Terrorism and Mass Murder."

Noting that the site of the terrorist bombing of the World Trade Center was named “Ground Zero,” we revisit how the League of Nations and the United States adopted terrorist bombing as standard operational procedure in air warfare during World War II.

At that time, the Allied forces bombed civilian cities in Japan and Germany under the pretext of psychological warfare in the era of “total war.”

In particular, the fact that the term “ground zero,” which used to refer to the sites of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, has been monopolized as a code for American victims after 9/11, sharply points out that the United States has shown no self-reflection on the mass murder of civilians it has committed in the past.

Through this, we reflect on the annihilation-style “shock and awe” strategy and develop our reasons for using the atomic bomb.

This shock and awe strategy was later replicated in the invasion of Iraq.

Part 3, "War and Occupation? Gaining Peace, Losing Peace," compares and analyzes the occupations of Japan and Iraq.

The author emphasizes that the 'success' of the Japanese occupation and the 'failure' of the Iraq occupation are not simple contrasts.

It points out that during the Japanese occupation, American rulers also exhibited problems such as ignorance of language and culture, ethnocentrism, and arrogance, but unlike in Iraq, these did not lead to fatal consequences.

John Dower finds significant “convergence of a sort” between Japanese and Iraqi occupation policies.

While policies like disbanding the military and purging public officials were successful in Japan, they had disastrous consequences in Iraq, a consequence of the 21st-century American imperial presidency's market-fundamentalist approach and its neglect of nation-building.

The Bush administration's groupthink, he argues, ignored officials' concerns and turned Iraq into a testing ground for "free-market" ideology, ultimately contributing to the occupation's failure.

From 'Imperialism' to 'The Dynamics of Modern Society'

Insightful comparative studies

John Dower's research goes beyond simple historical comparison.

He wrote "Cultures of War" by rejecting traditional regional studies or cultural determinism based on the "clash of civilizations" perspective, and focusing on comparing and analyzing the diverse cultures of modernity itself.

That is, it focuses on the cultural patterns created by the very phenomenon of violence and war.

In particular, it meticulously analyzes how specific lessons learned after World War II, such as asymmetric warfare, insurgency, national and transnational pride, smart power versus hard power, and the backlash of arrogance and negligence, were ignored in the invasion of Iraq.

The author also notes the similarities between the 2008 financial crash and the cultural pathology of war.

We find that secular priests, herd behavior, failures in risk assessment, wishful thinking disguised as rationality, and a lack of historical imagination are equally prevalent in both war and finance.

This overlap between the behavior of seemingly cool-headed and rational war makers and money makers armed with cutting-edge financial engineering provides a crucial analysis of the dynamics of modern society, leading to reflections on individual behavior and organizational pathology.

What should we learn from history?

What implications does John Dower's analysis have for Korean society in the 21st century? In his introduction, Professor Emeritus Kim Dong-chun of Sungkonghoe University points out, "For Koreans, who were unable to exercise independent command throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, the history of American intervention in the Asian wars is an ongoing one." He poses the weighty question, "When will Koreans be able to interpret and write the history of 20th-century wars from their own perspectives and perspectives?"

This book analyzes how the logic and rhetoric of war condone violence and how its memory is selectively constructed. It offers a profound perspective on the "culture of war" for those of us living amidst the geopolitical tensions of East Asia and the division of the Korean Peninsula.

He also brilliantly analyzed the cultural pathologies of individuals and organizations, the arrogance and self-righteousness of war planners, the irrational militarism, and the contradictions of imperial rulers.

This analysis provides broad insights that can be applied to structural problems in modern society, and offers many implications for our society.

John Dower, an expert on US-Japan relations,

Dissecting the War Cultures of the US and Japan

The Dynamics and Pathology of Modern Warfare

The Intellectual and Historical Roots of the 'War on Terror'

A Comparative Study of American and Japanese Militarism

*2010 National Book Award and Los Angeles Times Book Award finalist

*The Culture of War Through 122 Historical Visuals

Now turning to a larger canvas, John Dower presents Cultures of War: Pearl Harbor/Hiroshima/9-11/Iraq (Philos Series No. 34), a comparative study of an ambitious research project on the dynamics and pathologies of modern warfare.

This book analyzes the cultural patterns of modern war by examining the culture of war revealed through four events: the attack on Pearl Harbor, the bombing of Hiroshima, the 9/11 attacks, and the invasion of Iraq under the pretext of the war on terror.

The issues and topics the author examines as “culture of war” are as follows.

Failures of information and imagination, selective memory and collective forgetting, “strategic imbecility,” secular thinking based on military and religious beliefs, the contradiction between democracy and the imperial presidency (“unitary executive power”), the increasingly blatant rhetoric of holy war, and the targeting of non-combatants (an undeniable logic of mass murder).

John Dower's The Culture of War focuses on the arrogance and hypocrisy of war planners, comprehensively examining how the exercise of seemingly "rational choice" actually leads to symbols of irrationality and irresponsibility, and reveals how the culture of war is formed and sustained.

In the end, it suggests the possibility of “shared cultures of peace and reconciliation” and seeks hope for transcending the culture of war.

The author offers this as a reflection that goes beyond the behavior and pathology of individuals and institutions.

“I want to deal with evil seriously.

Double standards and hypocrisy are other recurring themes, as is the powerful role of memory and grief.

Tragedy is not a popular concept in social science because it is not easily modeled (like ambivalent ambiguity and irrationality).

I started out in the humanities and ended up majoring in history, and for me, tragedy, like evil, seems essential to understanding our war culture.

The use and misuse of history, and its literal disregard, has become another subtext.” ― From the introduction, “The Evolution of Inquiry” (pp. 45-46)

Pearl Harbor, Hiroshima, 9/11, Iraq

A monumental analysis that spans four wars.

“How is violence and aggression justified?”

· The selective memory and intentional forgetting caused by the collusion of the American and Japanese ruling classes have resulted in the sacrifices of both the North and South Korean people on the Korean Peninsula.

Kim Dong-chun, Professor Emeritus, Sungkonghoe University

From the Pearl Harbor attack to the 9/11 terrorist attacks, the author views the past not as mere historical facts, but as a dialogue with the present.

― Park Tae-gyun, Professor, Graduate School of International Studies, Seoul National University

· Drawing on a lifetime of reflection and academic achievement, this book sharply illuminates the wishful thinking, arrogance, and delusion that characterize modern warfare! ― National Book Award Nominee Summary

"The Culture of War" is a significant study that examines the origins of the imperialist logic of modernization and civilization, focusing on the institutional, intellectual, and psychological pathologies of modern war, and how violence and aggression are justified, along with 122 historical visuals.

This book is largely divided into three parts.

Each part reveals the structure of modern warfare, beginning with the tragedy of preemptive strikes brought about by intelligence failures and self-deception (Part 1) and tracing the shadow of mass murder that leads to terrorism and retaliation (Part 2).

Furthermore, it illuminates the paradox of democracy revealed in the process of occupation rule (Part 3) and analyzes how these three aspects form a vicious cycle of imperialist violence.

In addition to this organic analysis, what the author weaves together is “language.”

John Dower analyzes how the rhetoric of war becomes a trap that advocates violence, while simultaneously capturing the paradox that the very language of “peace, freedom, and justice” becomes a tool for waging war regardless of camp.

This goes beyond cynical propaganda; it exposes the essential contradictions of modern warfare through the way in which the culture of war appropriates the language of peace.

Dissecting the Arrogance and Oblivion of Imperialism

Part 1, "Pearl Harbor as Code? Chosen Wars and Intelligence Failures," analyzes the similarities between the intelligence failures and surprise attacks experienced by the United States in 1941 and 2001.

The author points out that such catastrophic events can be a gift to those in power, and compares the crisis responses of the Franklin Roosevelt and Bush administrations.

In particular, he notes the similarities in the “strategic stupidity” of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941 and the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003, noting that while both sides were tactically brilliant, they seriously misjudged the enemy’s psychology and capabilities.

This analysis extends to the Bush administration's "Bush Doctrine" of preemptive strikes in 2003, revealing the tragic pattern of "wars of one's own choosing" demonstrated by Japan in 1941, al-Qaeda in 2001, and the United States in 2003.

Part 2 covers "Ground Zero 1945 and Ground Zero 2001: Terrorism and Mass Murder."

Noting that the site of the terrorist bombing of the World Trade Center was named “Ground Zero,” we revisit how the League of Nations and the United States adopted terrorist bombing as standard operational procedure in air warfare during World War II.

At that time, the Allied forces bombed civilian cities in Japan and Germany under the pretext of psychological warfare in the era of “total war.”

In particular, the fact that the term “ground zero,” which used to refer to the sites of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, has been monopolized as a code for American victims after 9/11, sharply points out that the United States has shown no self-reflection on the mass murder of civilians it has committed in the past.

Through this, we reflect on the annihilation-style “shock and awe” strategy and develop our reasons for using the atomic bomb.

This shock and awe strategy was later replicated in the invasion of Iraq.

Part 3, "War and Occupation? Gaining Peace, Losing Peace," compares and analyzes the occupations of Japan and Iraq.

The author emphasizes that the 'success' of the Japanese occupation and the 'failure' of the Iraq occupation are not simple contrasts.

It points out that during the Japanese occupation, American rulers also exhibited problems such as ignorance of language and culture, ethnocentrism, and arrogance, but unlike in Iraq, these did not lead to fatal consequences.

John Dower finds significant “convergence of a sort” between Japanese and Iraqi occupation policies.

While policies like disbanding the military and purging public officials were successful in Japan, they had disastrous consequences in Iraq, a consequence of the 21st-century American imperial presidency's market-fundamentalist approach and its neglect of nation-building.

The Bush administration's groupthink, he argues, ignored officials' concerns and turned Iraq into a testing ground for "free-market" ideology, ultimately contributing to the occupation's failure.

From 'Imperialism' to 'The Dynamics of Modern Society'

Insightful comparative studies

John Dower's research goes beyond simple historical comparison.

He wrote "Cultures of War" by rejecting traditional regional studies or cultural determinism based on the "clash of civilizations" perspective, and focusing on comparing and analyzing the diverse cultures of modernity itself.

That is, it focuses on the cultural patterns created by the very phenomenon of violence and war.

In particular, it meticulously analyzes how specific lessons learned after World War II, such as asymmetric warfare, insurgency, national and transnational pride, smart power versus hard power, and the backlash of arrogance and negligence, were ignored in the invasion of Iraq.

The author also notes the similarities between the 2008 financial crash and the cultural pathology of war.

We find that secular priests, herd behavior, failures in risk assessment, wishful thinking disguised as rationality, and a lack of historical imagination are equally prevalent in both war and finance.

This overlap between the behavior of seemingly cool-headed and rational war makers and money makers armed with cutting-edge financial engineering provides a crucial analysis of the dynamics of modern society, leading to reflections on individual behavior and organizational pathology.

What should we learn from history?

What implications does John Dower's analysis have for Korean society in the 21st century? In his introduction, Professor Emeritus Kim Dong-chun of Sungkonghoe University points out, "For Koreans, who were unable to exercise independent command throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, the history of American intervention in the Asian wars is an ongoing one." He poses the weighty question, "When will Koreans be able to interpret and write the history of 20th-century wars from their own perspectives and perspectives?"

This book analyzes how the logic and rhetoric of war condone violence and how its memory is selectively constructed. It offers a profound perspective on the "culture of war" for those of us living amidst the geopolitical tensions of East Asia and the division of the Korean Peninsula.

He also brilliantly analyzed the cultural pathologies of individuals and organizations, the arrogance and self-righteousness of war planners, the irrational militarism, and the contradictions of imperial rulers.

This analysis provides broad insights that can be applied to structural problems in modern society, and offers many implications for our society.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: December 20, 2024

- Format: Hardcover book binding method guide

- Page count, weight, size: 792 pages | 152*225*40mm

- ISBN13: 9791171179305

- ISBN10: 1171179308

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)