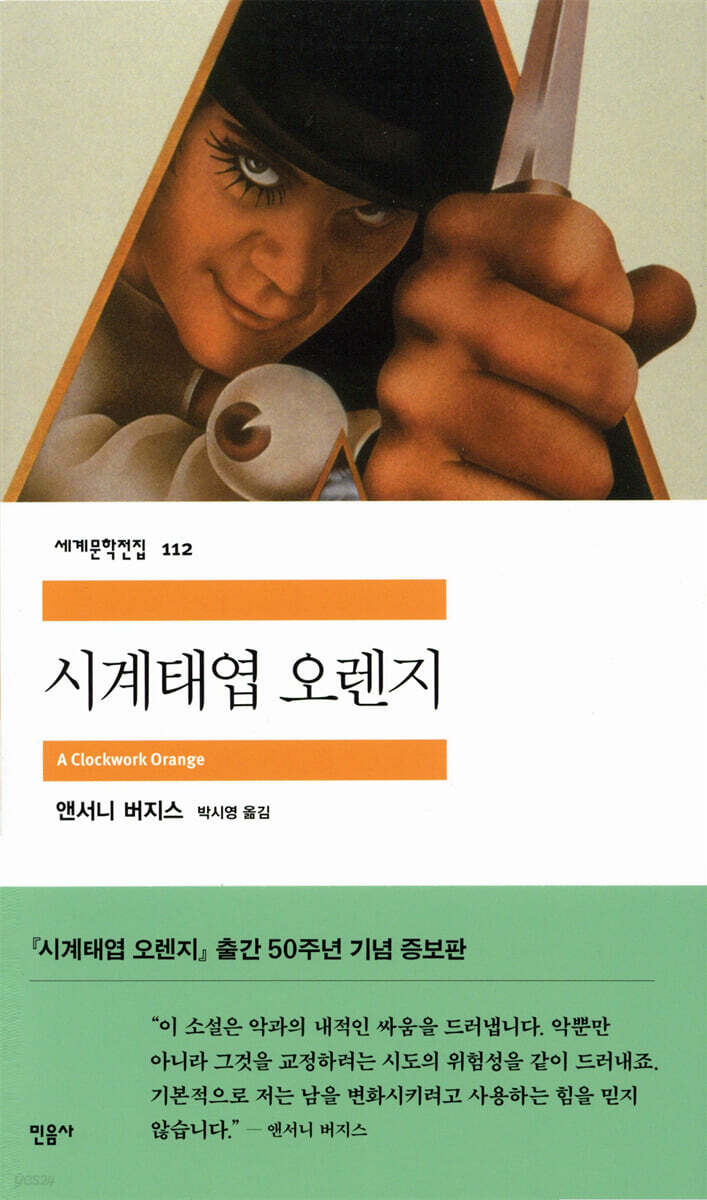

A Clockwork Orange

|

Description

Book Introduction

A 20th-century work that questions the meaning of human free will and morality. The original novel of Stanley Kubrick's film [A Clockwork Orange] Expanded edition commemorating the 50th anniversary of publication Since its publication in England in 1962, "A Clockwork Orange" has been a source of constant controversy and enthusiasm, and has become a classic of the 20th century. As the title suggests, this novel presents a reflection on the human condition, which can only move when the spring is wound by an external force. This work, which criticizes the oppression of state power and defends human free will while reflecting on violence and sin, boldly borrows contemporary slang and neologisms and introduces musical elements into the narrative format, thereby achieving a major innovation in novel technique. This book is a translation of the expanded edition published in 2012 to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the publication of A Clockwork Orange, and includes editor's notes, a slang dictionary, an epilogue by Anthony Burgess and several essays, unpublished interviews, the 1961 typescript, and a collection of essays by Malcolm Bradbury, A. Reviews by authors such as S. Byatt are included as appendices to help readers understand the work. |

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Introduction / Andrew Bizwell 7

A Clockwork Orange

Part 1, Chapter 35

Part 2 127

Part 3 197

Editor's Note 273

Nadsat Glossary 289

Prologue to A Clockwork Orange: The Musical / Anthony Burgess 301

Epilogue: A Short Tale About the Young and the Green / Anthony Burgess 312

Essays, Journals, and Reviews

The Russians / Anthony Burgess 327

Clockwork Marmalade / Anthony Burgess 338

Excerpt from an unpublished interview with Anthony Burgess 348

Program Notes for "A Clockwork Orange 2004" / Anthony Burgess 357

Ludwig van, review of Maynard Solomon's Beethoven / Anthony Burgess 363

The Ecstatic Golden Crimson / Anthony Burgess 371

A Clockwork Orange / Kingsley Amis 384

The New Novel / Malcolm Bradbury 387

Horror Show / Christopher Riggs 389

All Life is One: The Clockwork Bible, or Mr. Enderby's Apocalypse / A.

S. Byatt 409

Review / Stanley Hedger Hyman 416

The Last Word on Violence / Anthony Burgess 430

From Anthony Burgess' 1961 typewritten manuscript for A Clockwork Orange

Anthony Burgess's A Clockwork Orange (1961) 435

Commentary on the work 441

Translator's Note to the Augmented Edition 448

Author's Chronology 451

A Clockwork Orange

Part 1, Chapter 35

Part 2 127

Part 3 197

Editor's Note 273

Nadsat Glossary 289

Prologue to A Clockwork Orange: The Musical / Anthony Burgess 301

Epilogue: A Short Tale About the Young and the Green / Anthony Burgess 312

Essays, Journals, and Reviews

The Russians / Anthony Burgess 327

Clockwork Marmalade / Anthony Burgess 338

Excerpt from an unpublished interview with Anthony Burgess 348

Program Notes for "A Clockwork Orange 2004" / Anthony Burgess 357

Ludwig van, review of Maynard Solomon's Beethoven / Anthony Burgess 363

The Ecstatic Golden Crimson / Anthony Burgess 371

A Clockwork Orange / Kingsley Amis 384

The New Novel / Malcolm Bradbury 387

Horror Show / Christopher Riggs 389

All Life is One: The Clockwork Bible, or Mr. Enderby's Apocalypse / A.

S. Byatt 409

Review / Stanley Hedger Hyman 416

The Last Word on Violence / Anthony Burgess 430

From Anthony Burgess' 1961 typewritten manuscript for A Clockwork Orange

Anthony Burgess's A Clockwork Orange (1961) 435

Commentary on the work 441

Translator's Note to the Augmented Edition 448

Author's Chronology 451

Detailed image

Into the book

“That treatment has never been used before.

Even in this prison, number 6655321.

'He' is also deeply skeptical about that.

I have to say that I agree with that meeting.

The question is whether that therapy can truly make people good.

Goodness comes from within, number 6655321.

Goodness is something we must choose.

“When you can’t choose, you can’t be truly human.” --- p.138~139

“You will be a good boy, number 6655321, my child.

Never again will I have the desire to wield violence or do anything that would disturb the peace of the nation.

I want you to consider all of that.

“I wish you would be really clear about that yourself.” --- p.153

“It might not be good to be good, 6655321.

Being good can be a terrible thing.

Now that I think about it, I think it's a contradiction.

I'm going to have trouble sleeping for days because of this.

What does God want? Does God desire goodness itself or the choice of good? In some sense, isn't someone who chooses evil better than someone who must accept a goodness imposed on them? (……)" --- p.154

“Control is always difficult.

Because the world is one, and life is one.

Even the sweetest and most dreamlike of human acts involve some degree of violence, such as acts of love or music.

You have to take a chance and make a choice, kid.

“Up until now, the choice has been entirely yours.” --- p.180

“Me, me, me.

"What the hell do I want to do? What am I doing here? Am I some kind of beast or a dog?" At these words, the men started yelling at me, making a lot of noise.

So I shouted louder.

"Am I some kind of wind-up orange?" --- p.193

“This child will become a true Christian,” cried Dr. Brodsky.

“I am ready to turn the other cheek, to be crucified rather than be crucified, and the thought of killing a fly will bring me real pain.” --- p.195

“You, in my opinion, have committed a sin.

But the punishment for him was too harsh.

They made you into something other than human.

You no longer have the right to choose.

You have become accustomed to only doing what society approves of.

A small machine that can only do good things.

Now I understand clearly about the conditioned reflex technique.

“Music, sexual activity, literature and art—all these things are now clearly sources of pain rather than pleasure.” --- p.229

Yeah, yeah, that's it.

Youth has to go, right?

But in some ways, youth can be seen as something beastly.

No, it's not really a beast, it's more like a small doll sold on the street.

A doll made of tin and a spring mechanism, with a winding handle on the outside. When you wind it up and release it, it walks.

If you walk in a straight line, you'll end up bumping into things around you, but that can't be helped.

Youth is like one of those little machines.

--- p.270

And where I'm going now, you guys, it's a path that only I can take.

Tomorrow, too, fragrant flowers will bloom, the stinking world will turn, stars and moon will rise in the sky, and your old friend Alex will be alone, looking for a mate.

It's a very dirty and filthy world, you guys.

Now, goodbye to your comrades.

And a big hoot for the other guys in this story.

Go eat some shit.

But sometimes you have to remember the Alex of the past.

Amen, damn it.

Even in this prison, number 6655321.

'He' is also deeply skeptical about that.

I have to say that I agree with that meeting.

The question is whether that therapy can truly make people good.

Goodness comes from within, number 6655321.

Goodness is something we must choose.

“When you can’t choose, you can’t be truly human.” --- p.138~139

“You will be a good boy, number 6655321, my child.

Never again will I have the desire to wield violence or do anything that would disturb the peace of the nation.

I want you to consider all of that.

“I wish you would be really clear about that yourself.” --- p.153

“It might not be good to be good, 6655321.

Being good can be a terrible thing.

Now that I think about it, I think it's a contradiction.

I'm going to have trouble sleeping for days because of this.

What does God want? Does God desire goodness itself or the choice of good? In some sense, isn't someone who chooses evil better than someone who must accept a goodness imposed on them? (……)" --- p.154

“Control is always difficult.

Because the world is one, and life is one.

Even the sweetest and most dreamlike of human acts involve some degree of violence, such as acts of love or music.

You have to take a chance and make a choice, kid.

“Up until now, the choice has been entirely yours.” --- p.180

“Me, me, me.

"What the hell do I want to do? What am I doing here? Am I some kind of beast or a dog?" At these words, the men started yelling at me, making a lot of noise.

So I shouted louder.

"Am I some kind of wind-up orange?" --- p.193

“This child will become a true Christian,” cried Dr. Brodsky.

“I am ready to turn the other cheek, to be crucified rather than be crucified, and the thought of killing a fly will bring me real pain.” --- p.195

“You, in my opinion, have committed a sin.

But the punishment for him was too harsh.

They made you into something other than human.

You no longer have the right to choose.

You have become accustomed to only doing what society approves of.

A small machine that can only do good things.

Now I understand clearly about the conditioned reflex technique.

“Music, sexual activity, literature and art—all these things are now clearly sources of pain rather than pleasure.” --- p.229

Yeah, yeah, that's it.

Youth has to go, right?

But in some ways, youth can be seen as something beastly.

No, it's not really a beast, it's more like a small doll sold on the street.

A doll made of tin and a spring mechanism, with a winding handle on the outside. When you wind it up and release it, it walks.

If you walk in a straight line, you'll end up bumping into things around you, but that can't be helped.

Youth is like one of those little machines.

--- p.270

And where I'm going now, you guys, it's a path that only I can take.

Tomorrow, too, fragrant flowers will bloom, the stinking world will turn, stars and moon will rise in the sky, and your old friend Alex will be alone, looking for a mate.

It's a very dirty and filthy world, you guys.

Now, goodbye to your comrades.

And a big hoot for the other guys in this story.

Go eat some shit.

But sometimes you have to remember the Alex of the past.

Amen, damn it.

--- p.271~272

Publisher's Review

“No government should consider it a victory to turn respectable young people into wind-up machines.

“That’s something only a government that prides itself on oppression would do.”

A 20th-century work that questions the meaning of human free will and morality.

The original novel of Stanley Kubrick's film "A Clockwork Orange"

Expanded edition to commemorate the 50th anniversary of publication.

Editor's notes, a slang dictionary, an epilogue and several essays by Anthony Burgess, unpublished interviews, a 1961 typescript, and Malcolm Bradbury, A.

Includes reviews by authors such as S. Byatt.

ㆍSpeed and energy that makes your hair stand on end.

It is a fascinating novel that deals with Orwell's vision of the future.

-The New York Times

ㆍAnthony Burgess's work may seem unpleasant and shocking, but it is an uncommon philosophical novel.

-"time"

ㆍI don't know any writer who uses language as masterfully as Burgess.

-William Burroughs

ㆍAnthony Burgess is a wonderful intellectual and a compassionate soul who embraces the world.

-John Updike

■ A thorough defense of human free will

The most important and controversial themes of this work recur in the speeches of the characters, the author Alexander and the prison priest.

Without individual choice and free will, humans would no longer be fully human, but would be nothing more than passive mechanical devices, like a wind-up orange.

This is true not only at the individual level but also in social change.

Any social decision made without the choice and consent of its members is fundamentally meaningless.

However, this unconditional affirmation of free will, intertwined with the protagonist Alex's freedom of indiscriminate violence, demands a more acute awareness of the problem.

By exaggerating the violence Alex commits and the harm he inflicts on the community, Burgess asks the fundamental question: "If we defend individual freedom, must we also recognize the freedom to commit violence?"

By establishing Alex as a character who defies all conventional wisdom about good and evil and the limits of freedom, Burgess attempts to shatter the conventional logic of freedom and ethics.

Alex commits a crime, but he is still a minor, only fifteen years old, and is unaware of the repercussions or implications of his actions.

They also have an aversion to the socially controlling nature of popular culture and are also fans of high culture.

As an immature character who is neither absolutely good nor evil, a perfect rebel who opposes all control and desires absolute freedom but is unaware of the limits of that freedom, Alex faithfully portrays the situation of modern people caught in ethical, cultural, and worldview self-contradiction.

For modern people, good and evil are not given a priori, whether they be religious virtues, community norms, or legal rules, and likewise, free will is not oriented toward either good or evil.

Burgess argues that when any coercion or oppression is applied here, that is, when it is not a purely individual choice, it cannot be acknowledged.

■ Insight into the Roots of Sin

The London of the future, the setting of the work, is a dark dystopia where crime runs rampant and the social control to combat it is as violent as the crime itself.

State institutions such as schools and prisons serve no purpose; they only serve to separate conformist and non-conformist individuals.

It is unclear whether Alex's violence and deviance were caused by this environment, but his experience in prison after his arrest demonstrates the futility of trying to change human nature through environmental factors.

The Ludovico treatment that Alex volunteers for is an extreme form of environmental determinism that seeks to control human criminality through artificial experimentation.

The subject loses his or her subjectivity as a human being and the possibility of self-change through his or her own choice.

For Burgess, the error of this kind of environmental determinism lies in the fact that the very idea of seeking to trace the origins of evil presupposes the fiction of a kind of sterile human being, and the possibility of artificial interventions that could control or alter the complex and multifaceted life histories of human beings.

Burgess's paradoxical assertion, made through the prison priest's mouth, that "wouldn't a man who chooses evil be better than one who must accept the good that is forced upon him?" is a counter-question about what is more humane, and that on that basis we should pursue the possibility of improving the lives of individuals and the conditions of the community.

If so, the root of human sin lies in the fact that throughout human history, we have been increasingly deprived of the opportunity to question human truth, that is, to reflect on our own thoughts and actions, and this has become even more severe in modern times.

In the face of external authority and threats from myth, religion, and social mechanisms, the space for an individual to think and reflect freely has been diminishing.

In particular, as the mechanisms of social control become more sophisticated and the influence of mass media grows absolutely, it can be said that the position of humans as subjects who think and reflect has become narrower.

As the title suggests, modern people, who live passively with a clockwork mechanism, are losing the ability to reflect on themselves, and are also in danger of losing their sense of ethics and morality, and this condition soon becomes the root of sin.

■ Musical composition and innovative language

Burgess was a writer, a classical music enthusiast, and a composer.

One of his interests was integrating musical elements into literature, and A Clockwork Orange is the culmination of such efforts.

This work, which is structured in three parts, consists of seven chapters each.

And the latter half of Part 3 forms a counterpoint by formally repeating the first half of Part 1, but with a reversal in content.

This technique of reversal has an effect similar to the rondo form of a sonata or the ascent and descent of a symphony.

For example, in Part 1, Chapter 3, there is a scene where Alex sits in the Koroba Milk Bar and listens to a beautiful aria about death, and in Part 3, Chapter 5, he is tortured by the music until he attempts suicide.

In addition to the musical composition, the work's distinct personality is well expressed in the teenage slang and idiom, NADSAT, used by Alex and his friends.

The unique vocabulary in the work was created based on Russian and inspired by 'Cockney', a dialect spoken in the London area at the time.

He was so interested in language that he published books on linguistics, and he also devoted himself to research on the characteristics of everyday language and literary language.

In this work, the beer invented by Burgess reveals the social alienation, deviance, and exclusivity of Alex and his peers, and also has the effect of making the reader constantly infer the meaning of words based on context and phonetic similarity.

His view of language, which finds the characteristics of literary language in doubts and reflections on everyday language, is intertwined with the theme of his work, which is the exploration of humans as reflective subjects.

“That’s something only a government that prides itself on oppression would do.”

A 20th-century work that questions the meaning of human free will and morality.

The original novel of Stanley Kubrick's film "A Clockwork Orange"

Expanded edition to commemorate the 50th anniversary of publication.

Editor's notes, a slang dictionary, an epilogue and several essays by Anthony Burgess, unpublished interviews, a 1961 typescript, and Malcolm Bradbury, A.

Includes reviews by authors such as S. Byatt.

ㆍSpeed and energy that makes your hair stand on end.

It is a fascinating novel that deals with Orwell's vision of the future.

-The New York Times

ㆍAnthony Burgess's work may seem unpleasant and shocking, but it is an uncommon philosophical novel.

-"time"

ㆍI don't know any writer who uses language as masterfully as Burgess.

-William Burroughs

ㆍAnthony Burgess is a wonderful intellectual and a compassionate soul who embraces the world.

-John Updike

■ A thorough defense of human free will

The most important and controversial themes of this work recur in the speeches of the characters, the author Alexander and the prison priest.

Without individual choice and free will, humans would no longer be fully human, but would be nothing more than passive mechanical devices, like a wind-up orange.

This is true not only at the individual level but also in social change.

Any social decision made without the choice and consent of its members is fundamentally meaningless.

However, this unconditional affirmation of free will, intertwined with the protagonist Alex's freedom of indiscriminate violence, demands a more acute awareness of the problem.

By exaggerating the violence Alex commits and the harm he inflicts on the community, Burgess asks the fundamental question: "If we defend individual freedom, must we also recognize the freedom to commit violence?"

By establishing Alex as a character who defies all conventional wisdom about good and evil and the limits of freedom, Burgess attempts to shatter the conventional logic of freedom and ethics.

Alex commits a crime, but he is still a minor, only fifteen years old, and is unaware of the repercussions or implications of his actions.

They also have an aversion to the socially controlling nature of popular culture and are also fans of high culture.

As an immature character who is neither absolutely good nor evil, a perfect rebel who opposes all control and desires absolute freedom but is unaware of the limits of that freedom, Alex faithfully portrays the situation of modern people caught in ethical, cultural, and worldview self-contradiction.

For modern people, good and evil are not given a priori, whether they be religious virtues, community norms, or legal rules, and likewise, free will is not oriented toward either good or evil.

Burgess argues that when any coercion or oppression is applied here, that is, when it is not a purely individual choice, it cannot be acknowledged.

■ Insight into the Roots of Sin

The London of the future, the setting of the work, is a dark dystopia where crime runs rampant and the social control to combat it is as violent as the crime itself.

State institutions such as schools and prisons serve no purpose; they only serve to separate conformist and non-conformist individuals.

It is unclear whether Alex's violence and deviance were caused by this environment, but his experience in prison after his arrest demonstrates the futility of trying to change human nature through environmental factors.

The Ludovico treatment that Alex volunteers for is an extreme form of environmental determinism that seeks to control human criminality through artificial experimentation.

The subject loses his or her subjectivity as a human being and the possibility of self-change through his or her own choice.

For Burgess, the error of this kind of environmental determinism lies in the fact that the very idea of seeking to trace the origins of evil presupposes the fiction of a kind of sterile human being, and the possibility of artificial interventions that could control or alter the complex and multifaceted life histories of human beings.

Burgess's paradoxical assertion, made through the prison priest's mouth, that "wouldn't a man who chooses evil be better than one who must accept the good that is forced upon him?" is a counter-question about what is more humane, and that on that basis we should pursue the possibility of improving the lives of individuals and the conditions of the community.

If so, the root of human sin lies in the fact that throughout human history, we have been increasingly deprived of the opportunity to question human truth, that is, to reflect on our own thoughts and actions, and this has become even more severe in modern times.

In the face of external authority and threats from myth, religion, and social mechanisms, the space for an individual to think and reflect freely has been diminishing.

In particular, as the mechanisms of social control become more sophisticated and the influence of mass media grows absolutely, it can be said that the position of humans as subjects who think and reflect has become narrower.

As the title suggests, modern people, who live passively with a clockwork mechanism, are losing the ability to reflect on themselves, and are also in danger of losing their sense of ethics and morality, and this condition soon becomes the root of sin.

■ Musical composition and innovative language

Burgess was a writer, a classical music enthusiast, and a composer.

One of his interests was integrating musical elements into literature, and A Clockwork Orange is the culmination of such efforts.

This work, which is structured in three parts, consists of seven chapters each.

And the latter half of Part 3 forms a counterpoint by formally repeating the first half of Part 1, but with a reversal in content.

This technique of reversal has an effect similar to the rondo form of a sonata or the ascent and descent of a symphony.

For example, in Part 1, Chapter 3, there is a scene where Alex sits in the Koroba Milk Bar and listens to a beautiful aria about death, and in Part 3, Chapter 5, he is tortured by the music until he attempts suicide.

In addition to the musical composition, the work's distinct personality is well expressed in the teenage slang and idiom, NADSAT, used by Alex and his friends.

The unique vocabulary in the work was created based on Russian and inspired by 'Cockney', a dialect spoken in the London area at the time.

He was so interested in language that he published books on linguistics, and he also devoted himself to research on the characteristics of everyday language and literary language.

In this work, the beer invented by Burgess reveals the social alienation, deviance, and exclusivity of Alex and his peers, and also has the effect of making the reader constantly infer the meaning of words based on context and phonetic similarity.

His view of language, which finds the characteristics of literary language in doubts and reflections on everyday language, is intertwined with the theme of his work, which is the exploration of humans as reflective subjects.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Publication date: April 25, 2022

- Page count, weight, size: 464 pages | 518g | 132*224*23mm

- ISBN13: 9788937461125

- ISBN10: 8937461129

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)