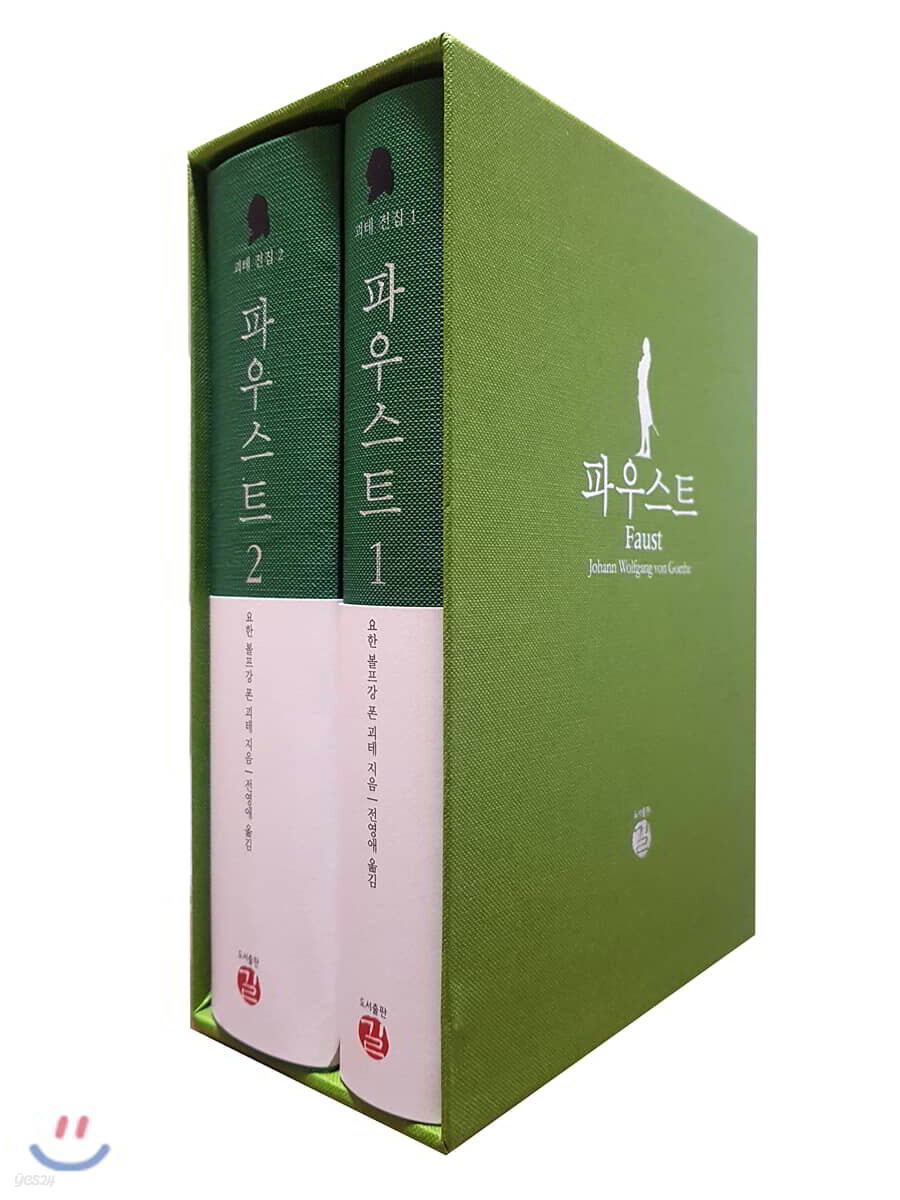

Faust set

|

Description

Book Introduction

The first work of the new translation of the complete Goethe works

The magnificent drama of the human Faust written by the great writer Goethe over the course of 60 years.

Professor Jeon Young-ae, a world-renowned Goethe researcher and poet,

12,111 lines of elaborate sentences properly translated “as poetry”

Read the German version

Gil Publishing, which has published classics and modern and contemporary ideas and theories in the humanities and social sciences that serve as the basis for interpreting and changing the world, is now introducing a new collection of works by the great German author Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832).

The reason why a humanities and social sciences publishing company is collecting and publishing Goethe's writings, which were mainly introduced in literary collections, is because it focuses on the fact that he was not only a writer who wrote immortal literary works such as 'Faust' and 'The Sorrows of Young Werther', but also a thinker who devoted his life to observing, experiencing, analyzing, and changing the society, history, and nature of his time.

This assessment is not entirely wrong when we look at Goethe's career, which began when he was invited to Weimar at the young age of 26 and spent his life tirelessly pursuing his ideas through diverse activities as a politician, writer, scholar, actor, and natural scientist. (He gave birth to German humanism, was a representative of the civic age, focused on generative and organic development, and was a politician who sought to improve the reality of Germany.) Moreover, we have never had a properly completed Goethe collection.

The translation of this [Complete Works of Goethe], scheduled to be in 20 volumes, will be carried out from beginning to end by Professor Emeritus Jeon Young-ae of the German Language and Literature Department at Seoul National University, who was the first Korean to receive the “Goethe Gold Medal,” the highest honor awarded by the German Goethe Society (2011).

This plan was also the translator's lifelong dream.

The first work is Goethe's masterpiece, Faust, which is being reintroduced this time.

The magnificent drama of the human Faust written by the great writer Goethe over the course of 60 years.

Professor Jeon Young-ae, a world-renowned Goethe researcher and poet,

12,111 lines of elaborate sentences properly translated “as poetry”

Read the German version

Gil Publishing, which has published classics and modern and contemporary ideas and theories in the humanities and social sciences that serve as the basis for interpreting and changing the world, is now introducing a new collection of works by the great German author Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832).

The reason why a humanities and social sciences publishing company is collecting and publishing Goethe's writings, which were mainly introduced in literary collections, is because it focuses on the fact that he was not only a writer who wrote immortal literary works such as 'Faust' and 'The Sorrows of Young Werther', but also a thinker who devoted his life to observing, experiencing, analyzing, and changing the society, history, and nature of his time.

This assessment is not entirely wrong when we look at Goethe's career, which began when he was invited to Weimar at the young age of 26 and spent his life tirelessly pursuing his ideas through diverse activities as a politician, writer, scholar, actor, and natural scientist. (He gave birth to German humanism, was a representative of the civic age, focused on generative and organic development, and was a politician who sought to improve the reality of Germany.) Moreover, we have never had a properly completed Goethe collection.

The translation of this [Complete Works of Goethe], scheduled to be in 20 volumes, will be carried out from beginning to end by Professor Emeritus Jeon Young-ae of the German Language and Literature Department at Seoul National University, who was the first Korean to receive the “Goethe Gold Medal,” the highest honor awarded by the German Goethe Society (2011).

This plan was also the translator's lifelong dream.

The first work is Goethe's masterpiece, Faust, which is being reintroduced this time.

index

Faust 1

time

Translator's Note | Like a poem, like a first translation

Chronology of the Writing of "Faust" | A Work Created Over a Lifetime

The rhythmic form and writing period of Faust

tribute

Preface on stage

Heavenly Prelude

Tragedy Part 1

Table of Contents for Volume 2

Tragedy Part 2

Act 1

Act 2

Act 3

Act 4

Act 5

Faust 2

time

Tragedy Part 2

Act 1

Act 2

Act 3

Act 4

Act 5

Table of Contents for Volume 1

Translator's Note | Like a poem, like a first translation

Chronology of the Writing of "Faust" | A Work Created Over a Lifetime

The rhythmic form and writing period of Faust

tribute

Preface on stage

Heavenly Prelude

Tragedy Part 1

time

Translator's Note | Like a poem, like a first translation

Chronology of the Writing of "Faust" | A Work Created Over a Lifetime

The rhythmic form and writing period of Faust

tribute

Preface on stage

Heavenly Prelude

Tragedy Part 1

Table of Contents for Volume 2

Tragedy Part 2

Act 1

Act 2

Act 3

Act 4

Act 5

Faust 2

time

Tragedy Part 2

Act 1

Act 2

Act 3

Act 4

Act 5

Table of Contents for Volume 1

Translator's Note | Like a poem, like a first translation

Chronology of the Writing of "Faust" | A Work Created Over a Lifetime

The rhythmic form and writing period of Faust

tribute

Preface on stage

Heavenly Prelude

Tragedy Part 1

Publisher's Review

A complete collection of 20 volumes, translated by a world-renowned Goethe scholar.

The Weimar edition (1887-1920), a complete collection published after Goethe's death, consists of 143 volumes of text alone, while the Munich and Frankfurt editions that came out later consist of 33 and 46 volumes, respectively, with each volume containing 1,000 to 1,500 pages.

Goethe left behind numerous works in various fields, including not only literary works such as novels, plays, and poems, but also literary and artistic theories, records of travel and observation, botany, zoology, optics, and meteorology. “His vast works contain profound historical insight and extraordinary insight in the observation, perception, and description of things” (Lee Gwang-ju, Professor Emeritus of Inje University).

Given this scale, it was unprecedented in the world of Goethe translation for a single translator to translate the entire collection.

Even in China, it is being promoted as a national project with 120 translators mobilized.

However, the reason Professor Jeon Yeong-ae took on this great task all by herself was because she “was sad and her pride was hurt that there was not a single decent Goethe collection in Korea.”

Of course, I cannot include all of the vast amount of writings in [Goethe's Complete Works], which I am translating alone, so I plan to select those that will be meaningful to our readers and publish them in twenty volumes.

This will serve as a valuable foundation for future research and acceptance of Goethe, and will be the first time that a single person has translated the complete works of Goethe. (The planned list of complete works is as follows.

1~2 Faust / 3 Poetry / 4 West and East Poetry Collection / 5~6 Drama / 7~8 Novel / 9 Poetry and Truth / 10 Italian Travels / 11 Year by Year: Records and Diaries / 12 Reality and Literature 1: German Refugees, Hermann and Dorothea, etc. / 13 Reality and Literature 2: French War Chronicles, Siege of Mainz, etc. / 14 Literary Theory and Art Theory / 15 Natural Science 1: Plant Theory / 16 Natural Science 2: Color Theory / 17 Natural Science 3: General Natural Science, Zoology, Mineralogy, Meteorology / 18 Letters 1: To Love / 19 Letters 2: To a Friend / 20 Letters 3: To the World)

The translator's lifelong passion and hard work, which resulted in the publication of the first volume of the [Complete Works of Goethe], "Faust," has resulted from his visits to Weimar, the city of Goethe, several times a year, to meet with German Goethe researchers, exchange opinions, and try to examine as many materials as possible from the archives.

In recognition of his efforts and research achievements, he was awarded the Goethe Gold Medal in 2011, which is equivalent to the Nobel Prize among Goethe researchers.

A New Translation of Faust: Like Poetry, Like a First Translation

There are already many Korean translations of ‘Faust’.

However, the reason I translated it again like this is because of the hope I had while reading the book for decades until the pages were scattered.

I wanted to translate Faust, a treasure trove of rhymes, into my own language, in a way that was at least a little like verse.

Although there are already various translations, it was difficult to find one that even hinted at the originality of this work as poetry.

For this reason, when readers think of 'Faust', they often think of it as a drama (difficult to read) or even as a unfortunate misunderstanding that it is a novel.

Even if I couldn't exactly translate that exquisite verse, I've long harbored a dream of being able to translate it in a way that conveys a little bit of its poetic quality, and that's how I began this new translation.

―From the “Translator’s Note” (hereinafter the same)

Goethe's masterpiece, Faust, is a play written in verse, not prose.

It also consists of 12,111 lines of poetry.

Depending on the character and scene, various rhyme patterns are used, allowing us to guess how much effort Goethe put into writing this work over a long period of time.

Since it is considered a must-read classic, there are already many Korean translations available.

However, existing Korean translations tend to read like prose because they focus on readability.

In order to help readers understand and read more smoothly, the editing process sometimes deviated from the original text's meaning or nuance, and the order of the lines was reversed in the process of translating German sentences to fit the Korean sentence structure.

Of course, this might make the work easier to read, but there was a risk that the rhythm and brilliance that Goethe had originally infused into the language of poetry would be dimmed or altered.

Professor Jeon Young-ae, who has carried around and read the original version of Faust for over 40 years, is also a poet who writes poetry in both Korean and German.

That is how special his affection for poetry is.

He had already translated Goethe's 『West-Eastern Poetry』 and 『The Complete Works of Goethe』, and was disappointed with the existing Korean translation of 『Faust』, which was also written as a poem. Therefore, the goal of this translation was to translate the language as if reading a poem, as if it were a poem.

To this end, I worked as if this was my first Korean translation, without referring to any existing Korean translations.

While translating, I did not look at the existing Korean translation at all.

As this is the first Korean translation, I translated it by looking only at the original.

I wanted to try it relying only on my eyes and vision.

I was afraid, but I thought it was time for someone to do it, and that the height of our German literature and the overall perspective of our literature had reached that level.

The task of transcribing the 12,111 lines in such a way that they retain their rhythm and connotative lingering feeling, and even their order is as close to the original text as possible, was by no means easy.

I did not write the explanations just to help you understand.

Emphasis was placed on preserving the poetic lingering feeling.

There was, of course, no way to fully capture the rich rhythms of the poem across the gaps of vastly different linguistic systems, across different eras and cultures, and across continents. (That is why the title of this commentary is “Like Poetry.”)

(How nice it would be if I could call it “poetry.”) Even though writing and studying poetry in Korean and even German was my lifelong profession, it was like that.

Still, I hope that at least some of the rhythm has been preserved.

Above all, I dream of being closely connected to the nuclear power plant.

Although numerous revisions were made to ensure that the original text's sentence order was followed while maintaining the intended meaning, it is impossible to accurately transfer the German sentence structure and rhythm of verse across time, history, and culture.

So, to make the difficult form of verse a little more visible and to enable German-speaking readers to experience the sophistication and fun of the poetic elements contained in Goethe's sentences, the original text is included alongside the translation.

This was inevitably a doubly difficult task for the translator, as he had to first decide which of the various editions of the original text to include, and even after deciding on the central edition, he had to refer to all the recent editions that reflected the achievements of Goethe research to confirm the final original text of the translation. (In principle, the original text was based on the Frankfurt edition (1989), which has been established as the definitive version.)

The Hamburg edition (1948), which had been the standard until then, was revised to follow the Frankfurt edition, and in doing so, Goethe's own final manuscript (1932) was referred to.

Above all, many symbols added by editors to aid the reader's understanding up to the Hamburg edition—Goethe himself was strict about symbols—and words corrected according to the grammar of the time have been returned to the original as close as possible.)

Although the text of Faust has not fundamentally changed because several major editions of the original text have been published in the meantime, I thought it would be good to have a new translation that thoroughly consults the new editions and is based on Goethe's handwritten manuscript that reflects his many efforts and revisions.

This also became one of the reasons for translating this work again.

And so, as the title of the translator's note suggests, I am presenting to readers a new version of 『Faust』, translated “like poetry, like a first translation.”

“As long as a person has a direction, he will wander.”

“As long as one strives, one wanders.” (Es irrt der Mensch, solang' er strebt.) This is a phrase that is often quoted as a word of encouragement to those who are lost and discouraged, and it is a regular in collections of famous quotes.

This passage is quoted from Faust.

This sentence encapsulates the grand drama of the human Faust.

Professor Jeon Young-ae translated this sentence, which has been translated as “Humans wander as long as they try,” as follows.

“As long as a person has a direction, he will wander.”

Here, the German word for “effort”, “streben,” of course has the meaning of “to strive,” which is defined as “to exert oneself with all one’s body and mind to achieve a goal.”

However, the underlying meaning is “to advance,” “to aim for,” and “to aspire to.”

For that reason, in this new translation, the translator translated this sentence as above.

This sentence has been translated as “Man wanders as long as he tries,” but it places too much emphasis on “effort,” so after much thought, I changed the translation.

This is because the German verb streben is a word that carries more of the feeling of inner surging than the meaning of working day and night or being devoted to work.

Above all, this work deals with the core and problems of modern and contemporary human life, driven by incessant desire.

The archetype of a human who makes a contract with the devil, which is often depicted in recent dramas and movies, appears here.

A man possessing a great deal of knowledge but filled with doubts enough to drink the poisoned cup ends up surrendering himself to the devil. However, what can a “modern” man, with his endless desire to experience and possess everything, acquire and what will be the end of his journey? This is the question posed by this work.

In this way, human desire, human life, and human beings are depicted in 『Faust』.

As an example, I chose the character Faust.

"Faust" is a work that needs no further explanation.

This is a work that Goethe began writing when he was twenty-two and continued writing for over sixty years, his entire life, until he was eighty-three, when he was near death.

Even among the world's most renowned classics, it is rare to find a work that one person devoted his or her life to.

His lifelong interests and concerns are reflected here.

"Faust" is a work that covers "3,000 years" of Northern and Southern Europe, from ancient Greco-Roman mythology through the Middle Ages (infused with the Bible) to modern times.

The world of Greco-Roman mythology and the Christian Middle Ages are interwoven, and the transition from the Middle Ages to the modern era is heavily highlighted (e.g., the issuance of paper money, the creation of artificial humans, etc.), while the issue of medieval or timeless 'salvation' is also significantly incorporated.

Today, here, I want to retell Faust not only because of the vast world it contains, but also because of the keen insight it offers into humanity and the world.

These deep and wide-ranging reflections, contained in sophisticated language that is sometimes orphaned, sometimes beautiful, sometimes obscure, and sometimes even comical, will have particular relevance in an age when humanity is becoming increasingly small and fragile.

“Even in the midst of dark impulses, good people are well aware of the right path.” (From “Heavenly Prelude” in “Faust”)

The Weimar edition (1887-1920), a complete collection published after Goethe's death, consists of 143 volumes of text alone, while the Munich and Frankfurt editions that came out later consist of 33 and 46 volumes, respectively, with each volume containing 1,000 to 1,500 pages.

Goethe left behind numerous works in various fields, including not only literary works such as novels, plays, and poems, but also literary and artistic theories, records of travel and observation, botany, zoology, optics, and meteorology. “His vast works contain profound historical insight and extraordinary insight in the observation, perception, and description of things” (Lee Gwang-ju, Professor Emeritus of Inje University).

Given this scale, it was unprecedented in the world of Goethe translation for a single translator to translate the entire collection.

Even in China, it is being promoted as a national project with 120 translators mobilized.

However, the reason Professor Jeon Yeong-ae took on this great task all by herself was because she “was sad and her pride was hurt that there was not a single decent Goethe collection in Korea.”

Of course, I cannot include all of the vast amount of writings in [Goethe's Complete Works], which I am translating alone, so I plan to select those that will be meaningful to our readers and publish them in twenty volumes.

This will serve as a valuable foundation for future research and acceptance of Goethe, and will be the first time that a single person has translated the complete works of Goethe. (The planned list of complete works is as follows.

1~2 Faust / 3 Poetry / 4 West and East Poetry Collection / 5~6 Drama / 7~8 Novel / 9 Poetry and Truth / 10 Italian Travels / 11 Year by Year: Records and Diaries / 12 Reality and Literature 1: German Refugees, Hermann and Dorothea, etc. / 13 Reality and Literature 2: French War Chronicles, Siege of Mainz, etc. / 14 Literary Theory and Art Theory / 15 Natural Science 1: Plant Theory / 16 Natural Science 2: Color Theory / 17 Natural Science 3: General Natural Science, Zoology, Mineralogy, Meteorology / 18 Letters 1: To Love / 19 Letters 2: To a Friend / 20 Letters 3: To the World)

The translator's lifelong passion and hard work, which resulted in the publication of the first volume of the [Complete Works of Goethe], "Faust," has resulted from his visits to Weimar, the city of Goethe, several times a year, to meet with German Goethe researchers, exchange opinions, and try to examine as many materials as possible from the archives.

In recognition of his efforts and research achievements, he was awarded the Goethe Gold Medal in 2011, which is equivalent to the Nobel Prize among Goethe researchers.

A New Translation of Faust: Like Poetry, Like a First Translation

There are already many Korean translations of ‘Faust’.

However, the reason I translated it again like this is because of the hope I had while reading the book for decades until the pages were scattered.

I wanted to translate Faust, a treasure trove of rhymes, into my own language, in a way that was at least a little like verse.

Although there are already various translations, it was difficult to find one that even hinted at the originality of this work as poetry.

For this reason, when readers think of 'Faust', they often think of it as a drama (difficult to read) or even as a unfortunate misunderstanding that it is a novel.

Even if I couldn't exactly translate that exquisite verse, I've long harbored a dream of being able to translate it in a way that conveys a little bit of its poetic quality, and that's how I began this new translation.

―From the “Translator’s Note” (hereinafter the same)

Goethe's masterpiece, Faust, is a play written in verse, not prose.

It also consists of 12,111 lines of poetry.

Depending on the character and scene, various rhyme patterns are used, allowing us to guess how much effort Goethe put into writing this work over a long period of time.

Since it is considered a must-read classic, there are already many Korean translations available.

However, existing Korean translations tend to read like prose because they focus on readability.

In order to help readers understand and read more smoothly, the editing process sometimes deviated from the original text's meaning or nuance, and the order of the lines was reversed in the process of translating German sentences to fit the Korean sentence structure.

Of course, this might make the work easier to read, but there was a risk that the rhythm and brilliance that Goethe had originally infused into the language of poetry would be dimmed or altered.

Professor Jeon Young-ae, who has carried around and read the original version of Faust for over 40 years, is also a poet who writes poetry in both Korean and German.

That is how special his affection for poetry is.

He had already translated Goethe's 『West-Eastern Poetry』 and 『The Complete Works of Goethe』, and was disappointed with the existing Korean translation of 『Faust』, which was also written as a poem. Therefore, the goal of this translation was to translate the language as if reading a poem, as if it were a poem.

To this end, I worked as if this was my first Korean translation, without referring to any existing Korean translations.

While translating, I did not look at the existing Korean translation at all.

As this is the first Korean translation, I translated it by looking only at the original.

I wanted to try it relying only on my eyes and vision.

I was afraid, but I thought it was time for someone to do it, and that the height of our German literature and the overall perspective of our literature had reached that level.

The task of transcribing the 12,111 lines in such a way that they retain their rhythm and connotative lingering feeling, and even their order is as close to the original text as possible, was by no means easy.

I did not write the explanations just to help you understand.

Emphasis was placed on preserving the poetic lingering feeling.

There was, of course, no way to fully capture the rich rhythms of the poem across the gaps of vastly different linguistic systems, across different eras and cultures, and across continents. (That is why the title of this commentary is “Like Poetry.”)

(How nice it would be if I could call it “poetry.”) Even though writing and studying poetry in Korean and even German was my lifelong profession, it was like that.

Still, I hope that at least some of the rhythm has been preserved.

Above all, I dream of being closely connected to the nuclear power plant.

Although numerous revisions were made to ensure that the original text's sentence order was followed while maintaining the intended meaning, it is impossible to accurately transfer the German sentence structure and rhythm of verse across time, history, and culture.

So, to make the difficult form of verse a little more visible and to enable German-speaking readers to experience the sophistication and fun of the poetic elements contained in Goethe's sentences, the original text is included alongside the translation.

This was inevitably a doubly difficult task for the translator, as he had to first decide which of the various editions of the original text to include, and even after deciding on the central edition, he had to refer to all the recent editions that reflected the achievements of Goethe research to confirm the final original text of the translation. (In principle, the original text was based on the Frankfurt edition (1989), which has been established as the definitive version.)

The Hamburg edition (1948), which had been the standard until then, was revised to follow the Frankfurt edition, and in doing so, Goethe's own final manuscript (1932) was referred to.

Above all, many symbols added by editors to aid the reader's understanding up to the Hamburg edition—Goethe himself was strict about symbols—and words corrected according to the grammar of the time have been returned to the original as close as possible.)

Although the text of Faust has not fundamentally changed because several major editions of the original text have been published in the meantime, I thought it would be good to have a new translation that thoroughly consults the new editions and is based on Goethe's handwritten manuscript that reflects his many efforts and revisions.

This also became one of the reasons for translating this work again.

And so, as the title of the translator's note suggests, I am presenting to readers a new version of 『Faust』, translated “like poetry, like a first translation.”

“As long as a person has a direction, he will wander.”

“As long as one strives, one wanders.” (Es irrt der Mensch, solang' er strebt.) This is a phrase that is often quoted as a word of encouragement to those who are lost and discouraged, and it is a regular in collections of famous quotes.

This passage is quoted from Faust.

This sentence encapsulates the grand drama of the human Faust.

Professor Jeon Young-ae translated this sentence, which has been translated as “Humans wander as long as they try,” as follows.

“As long as a person has a direction, he will wander.”

Here, the German word for “effort”, “streben,” of course has the meaning of “to strive,” which is defined as “to exert oneself with all one’s body and mind to achieve a goal.”

However, the underlying meaning is “to advance,” “to aim for,” and “to aspire to.”

For that reason, in this new translation, the translator translated this sentence as above.

This sentence has been translated as “Man wanders as long as he tries,” but it places too much emphasis on “effort,” so after much thought, I changed the translation.

This is because the German verb streben is a word that carries more of the feeling of inner surging than the meaning of working day and night or being devoted to work.

Above all, this work deals with the core and problems of modern and contemporary human life, driven by incessant desire.

The archetype of a human who makes a contract with the devil, which is often depicted in recent dramas and movies, appears here.

A man possessing a great deal of knowledge but filled with doubts enough to drink the poisoned cup ends up surrendering himself to the devil. However, what can a “modern” man, with his endless desire to experience and possess everything, acquire and what will be the end of his journey? This is the question posed by this work.

In this way, human desire, human life, and human beings are depicted in 『Faust』.

As an example, I chose the character Faust.

"Faust" is a work that needs no further explanation.

This is a work that Goethe began writing when he was twenty-two and continued writing for over sixty years, his entire life, until he was eighty-three, when he was near death.

Even among the world's most renowned classics, it is rare to find a work that one person devoted his or her life to.

His lifelong interests and concerns are reflected here.

"Faust" is a work that covers "3,000 years" of Northern and Southern Europe, from ancient Greco-Roman mythology through the Middle Ages (infused with the Bible) to modern times.

The world of Greco-Roman mythology and the Christian Middle Ages are interwoven, and the transition from the Middle Ages to the modern era is heavily highlighted (e.g., the issuance of paper money, the creation of artificial humans, etc.), while the issue of medieval or timeless 'salvation' is also significantly incorporated.

Today, here, I want to retell Faust not only because of the vast world it contains, but also because of the keen insight it offers into humanity and the world.

These deep and wide-ranging reflections, contained in sophisticated language that is sometimes orphaned, sometimes beautiful, sometimes obscure, and sometimes even comical, will have particular relevance in an age when humanity is becoming increasingly small and fragile.

“Even in the midst of dark impulses, good people are well aware of the right path.” (From “Heavenly Prelude” in “Faust”)

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: June 10, 2019

- Page count, weight, size: 1,512 pages | 145*210*80mm

- ISBN13: 9788964452103

- ISBN10: 8964452100

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)