sapient

|

Description

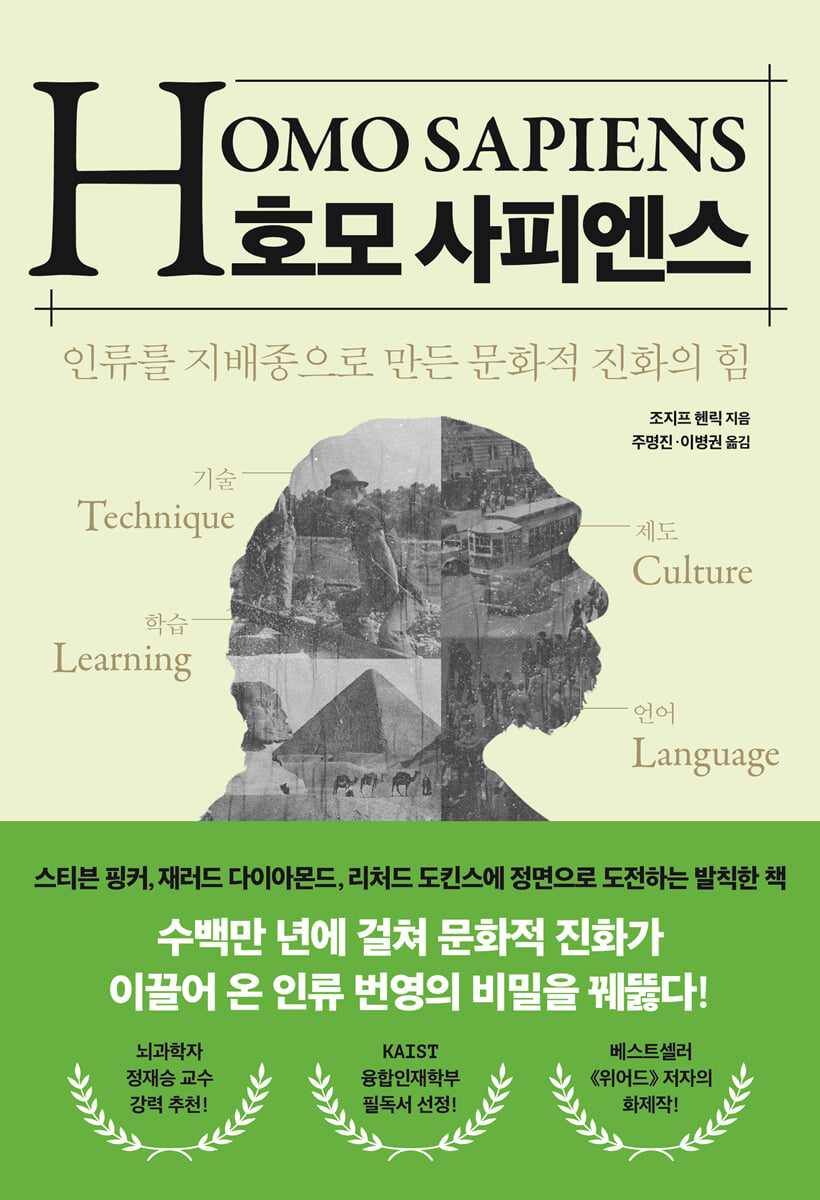

Book Introduction

★ Includes a special recommendation from Professor Jeong Jae-seung! ★

★ Selected for the KAIST Convergence Talent Department Reading List! ★

★ Highly recommended by world-renowned scholars Darren Acemoglu, Jonathan Haidt, and James Robinson ★

“More entertaining than Guns, Germs, and Steel, and more sassy than The Selfish Gene!”

“How was it that only Sapiens among the apes were able to achieve civilization and prosperity?”

A shocking book that changed the paradigm of human evolution!

Humans are not stronger than elephants and not faster than cheetahs.

They do not have developed the instinct to avoid poisonous plants, nor do they have a digestive system that can withstand poisonous plants.

But how did modern humans succeed in surviving and becoming the dominant species on Earth?

Professor Joseph Henrik of the Department of Human Evolutionary Biology at Harvard University has explored and researched these questions in depth across various disciplines, including anthropology, biology, and psychology, and has published the results in a single volume, “Homo Sapiens.”

The author traces back millions of years to the time when the Sapiens species began to dominate the world, and focuses on the fact that the special talent of Homo is not in individual intelligence or extraordinary mental abilities, but in the ability to cooperate and learn selectively as a group.

We trace the evolutionary implications of our species' unique trait of being able to reach solutions that individuals, while individually having limitations and weaknesses, cannot reach as a group.

And through this, it clearly reveals how humans in the past learned from others, imitated them, and achieved survival and development, and how our group cooperation and cultural evolution became the driving force behind our survival and evolution.

This book offers fresh perspectives and insights into dissecting and understanding the history of human cultural evolution from past to present, offering deep insight and wonder to readers seeking to broaden their understanding of the unique characteristics of the human species and the evolutionary context that underpins them.

★ Selected for the KAIST Convergence Talent Department Reading List! ★

★ Highly recommended by world-renowned scholars Darren Acemoglu, Jonathan Haidt, and James Robinson ★

“More entertaining than Guns, Germs, and Steel, and more sassy than The Selfish Gene!”

“How was it that only Sapiens among the apes were able to achieve civilization and prosperity?”

A shocking book that changed the paradigm of human evolution!

Humans are not stronger than elephants and not faster than cheetahs.

They do not have developed the instinct to avoid poisonous plants, nor do they have a digestive system that can withstand poisonous plants.

But how did modern humans succeed in surviving and becoming the dominant species on Earth?

Professor Joseph Henrik of the Department of Human Evolutionary Biology at Harvard University has explored and researched these questions in depth across various disciplines, including anthropology, biology, and psychology, and has published the results in a single volume, “Homo Sapiens.”

The author traces back millions of years to the time when the Sapiens species began to dominate the world, and focuses on the fact that the special talent of Homo is not in individual intelligence or extraordinary mental abilities, but in the ability to cooperate and learn selectively as a group.

We trace the evolutionary implications of our species' unique trait of being able to reach solutions that individuals, while individually having limitations and weaknesses, cannot reach as a group.

And through this, it clearly reveals how humans in the past learned from others, imitated them, and achieved survival and development, and how our group cooperation and cultural evolution became the driving force behind our survival and evolution.

This book offers fresh perspectives and insights into dissecting and understanding the history of human cultural evolution from past to present, offering deep insight and wonder to readers seeking to broaden their understanding of the unique characteristics of the human species and the evolutionary context that underpins them.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Recommendation_Jeong Jae-seung

Praise poured in for this book

preface

Chapter 1: The Enigmatic Primate

Chapter 2: Did we survive because we were smart?

Showdown: Apes vs. Humans · Memory Tests on Chimpanzees and College Students · The True Machiavellian

Chapter 3: Can You Survive If You Were Dropped on a Deserted Island?

Burke and Wills Expedition, Narváez Expedition, The Woman Who Survived Alone on an Island for 18 Years

Chapter 4: How to Make a Cultural Species

Skills and Success · Prestige · Self-Similarity: Gender and Ethnicity · Older People Generally Know More · Why Care What Others Think?: Conformity Transmission · Culturally Transmitted Suicide · Where is Mentalization Used? · Learning to Learn and Teach

Chapter 5: Culture Has Weakened Our Bodies

Big brains, rapid evolution, and slow development · Digesting outside the body: cooking food · How tools made us fat and weak · How water bottles and tracking made us long-distance runners · Thinking and learning about plants and animals

Chapter 6: Why Do Some People Have Blue Eyes?

Grain and ADH1B · Why Some Adults Can Drink Milk · The Culture-Gene Revolution · Genes and Race

Chapter 7: On the Origin of Trust

Contraindications during lactation and pregnancy? · Why do we add ash to corn water? · Fortune-telling and game theory · 'Overimitation' in the lab · Overcoming instinct: Why spicy peppers taste so good · Move over, natural selection

Chapter 8: Prestige, Power, and Menopause

The Core Elements of Prestige and Power · Why the Prominent Are Generous · Prestige and Experience · Leadership and the Evolution of Human Society

Chapter 9: In-Laws, Incest Taboos and Rituals

Social norms and the birth of community · From kinship to kinship · A fatherless society · Sociality and cooperation among hunter-gatherers · And further

Chapter 10: The Framework for Cultural Evolution Created by Intergroup Competition

How long has intergroup competition existed? · The expansion of hunter-gatherers

Chapter 11: Self-taming

How Altruism Is Like a Hot Pepper · It's Automatic · The Ethnic Stereotypes Created by Norms · Why Are Humans So Strong on Kinship-Based Altruism and Reciprocity · War, Foreign Threats, and Norm Adherence

Chapter 12: The Collective Brain

Back to the Lab! · Size and Interrelationships in the Real World · The Tasmanian Effect · Children vs. Chimpanzees and Monkeys · Are We Innately Dumber Than Neanderthals? · Tools and Norms Make Us Smarter

Chapter 13: Communication Tools with Rules

Communication repertoires are culturally adaptive · Culturally evolved complexity, efficiency, and learnability · Culturally evolved to be easy to learn · The synergy of hand movements, norms, gestures, and language · Culture and cooperation, and why actions speak louder than words · Summary

Chapter 14: The Culturally Adapted Brain and the Hormones of Honor

Wine, Men, and Songs · Driving in London to Modify the Hippocampus · The Glorious Hormone · Chemically Inert but Biologically Active

Chapter 15: The Threshold of Evolution

Chapter 16 Why were we human?

Two roads intertwine to form a bridge

Chapter 17: New Animals Created by Cultural Evolution

Why are humans unique? · Why are we so cooperative compared to other animals? · Why do we seem so smart compared to other animals? · Is all this still going on? · How will this change how we study history, psychology, economics, and anthropology? · Will this help us build anything?

Huzhou

References

Source of the illustration

Search

Praise poured in for this book

preface

Chapter 1: The Enigmatic Primate

Chapter 2: Did we survive because we were smart?

Showdown: Apes vs. Humans · Memory Tests on Chimpanzees and College Students · The True Machiavellian

Chapter 3: Can You Survive If You Were Dropped on a Deserted Island?

Burke and Wills Expedition, Narváez Expedition, The Woman Who Survived Alone on an Island for 18 Years

Chapter 4: How to Make a Cultural Species

Skills and Success · Prestige · Self-Similarity: Gender and Ethnicity · Older People Generally Know More · Why Care What Others Think?: Conformity Transmission · Culturally Transmitted Suicide · Where is Mentalization Used? · Learning to Learn and Teach

Chapter 5: Culture Has Weakened Our Bodies

Big brains, rapid evolution, and slow development · Digesting outside the body: cooking food · How tools made us fat and weak · How water bottles and tracking made us long-distance runners · Thinking and learning about plants and animals

Chapter 6: Why Do Some People Have Blue Eyes?

Grain and ADH1B · Why Some Adults Can Drink Milk · The Culture-Gene Revolution · Genes and Race

Chapter 7: On the Origin of Trust

Contraindications during lactation and pregnancy? · Why do we add ash to corn water? · Fortune-telling and game theory · 'Overimitation' in the lab · Overcoming instinct: Why spicy peppers taste so good · Move over, natural selection

Chapter 8: Prestige, Power, and Menopause

The Core Elements of Prestige and Power · Why the Prominent Are Generous · Prestige and Experience · Leadership and the Evolution of Human Society

Chapter 9: In-Laws, Incest Taboos and Rituals

Social norms and the birth of community · From kinship to kinship · A fatherless society · Sociality and cooperation among hunter-gatherers · And further

Chapter 10: The Framework for Cultural Evolution Created by Intergroup Competition

How long has intergroup competition existed? · The expansion of hunter-gatherers

Chapter 11: Self-taming

How Altruism Is Like a Hot Pepper · It's Automatic · The Ethnic Stereotypes Created by Norms · Why Are Humans So Strong on Kinship-Based Altruism and Reciprocity · War, Foreign Threats, and Norm Adherence

Chapter 12: The Collective Brain

Back to the Lab! · Size and Interrelationships in the Real World · The Tasmanian Effect · Children vs. Chimpanzees and Monkeys · Are We Innately Dumber Than Neanderthals? · Tools and Norms Make Us Smarter

Chapter 13: Communication Tools with Rules

Communication repertoires are culturally adaptive · Culturally evolved complexity, efficiency, and learnability · Culturally evolved to be easy to learn · The synergy of hand movements, norms, gestures, and language · Culture and cooperation, and why actions speak louder than words · Summary

Chapter 14: The Culturally Adapted Brain and the Hormones of Honor

Wine, Men, and Songs · Driving in London to Modify the Hippocampus · The Glorious Hormone · Chemically Inert but Biologically Active

Chapter 15: The Threshold of Evolution

Chapter 16 Why were we human?

Two roads intertwine to form a bridge

Chapter 17: New Animals Created by Cultural Evolution

Why are humans unique? · Why are we so cooperative compared to other animals? · Why do we seem so smart compared to other animals? · Is all this still going on? · How will this change how we study history, psychology, economics, and anthropology? · Will this help us build anything?

Huzhou

References

Source of the illustration

Search

Detailed image

.jpg)

Into the book

Let's say we take you and 49 of your coworkers and throw you into a survival game where you have to fight a squad of 50 capuchin monkeys from Costa Rica.

We will parachute both primate teams into a remote tropical forest in Central Africa.

And then we'll come back in two years and count the survivors from each team.

The team with more survivors wins.

Of course, no team will be allowed to take the equipment.

No matches, no water jugs, no knives, no shoes, no glasses, no antibiotics, no pots, no guns, no ropes.

(…) Let’s face it.

There is a high probability that the human team you are in will be defeated.

Whether your team has big brains and a lot of ego or not, you're probably going to lose badly to a bunch of monkeys.

If our large brains were useless for survival as hunter-gatherers in Africa, the continent where our species evolved, what purpose were they serving? How did we manage to expand into all the diverse environments across the globe?

---From "Chapter 1: The Mysterious Primate"

Our species' uniqueness, and its resulting ecological dominance, stems from the way cultural evolution has often worked over hundreds or even thousands of years, allowing us to assemble cultural adaptations.

The cultural adaptations I have highlighted in the above examples are tools and know-how for finding and processing food, locating water, cooking, and moving around.

But as you read this book, it will become clear that cultural adaptations include not only the things we can create, but also the way we think and the things we like.

---From "Chapter 3: Can You Survive If You Were Dropped on a Deserted Island?"

Natural selection has shaped us into a cultural species by altering our development in many ways.

(1) By shortening infancy and lengthening childhood, the body's growth was slowed down, but a growth spurt was added during adolescence.

(2) It has altered neural development in complex ways that allow our brains to be ahead of their time, yet still be able to expand rapidly and maintain plasticity.

Going forward, how our rapid genetic evolution, large adult brains, slow physical development, and progressive wiring become possible will be considered only as part of a larger set of characteristics.

These characteristics of our species, including the sexual division of labor, intensive parental investment, and the long post-reproductive period we associate with menopause, likely interact with cultural evolution in a number of crucial ways.

---From "Chapter 5: Culture Has Made Our Bodies Weak"

Ciguatera toxin is produced by certain marine microorganisms that thrive on dead coral reefs.

The poison accumulates as it moves up the food chain, reaching dangerous levels in some large, long-lived fish, including the species mentioned above.

Acute symptoms of poisoning that last about a week include diarrhea, vomiting, headache, itching, and a unique sensation of hot and cold sensations on the skin.

(…) Like other toxins, ciguatera probably accumulates in breast milk and could endanger nursing infants.

In adults, ciguerra poisoning has a low rate of death.

(…) This set of taboos constitutes a kind of cultural adaptation that selectively targets the most toxic species in women's regular diet, precisely at the time when mothers and children are most vulnerable.

To explore how this cultural adaptation emerged, we studied how women acquired these taboos and what kind of causal understandings they had.

During adolescence and young adulthood, we first learn these taboos from our mothers, mothers-in-law, and grandmothers.

---From “Chapter 7: On the Origin of Trust”

Amazingly, we can even speculate about the ancient brains of our ancestors, dating back roughly two million years ago.

Analysis of Oldowan tools suggests that 90 percent of their makers were right-handed.

This is unusual, as apes have no hand preference, and we have a dominant hand because the two hemispheres of our brains share the same role.

Typically, the human left brain focuses on language and tool use.

Consistent with this, the early Homo skull tentatively suggests expansions in areas known to be important for language, gesture, and tool use, and shows the emergence of a physical separation between the two hemispheres.

Consistent with the presence of tools and the culturally driven response to the synergy between tools for food processing and tools for communication, it seems likely that the neural division of labor that characterizes the modern human brain has already begun to emerge.

---From "Chapter 15: The Threshold of Evolution"

The answer to the question, 'Why are humans different?' is, 'We have crossed the Rubicon.'

Cultural evolution was cumulative, and then both this accumulating mass of information and its cultural products, like fire and food-sharing norms, developed into central driving forces in human genetic evolution.

The reason we appear so unique is that no other living animal has trodden this path, and those who have, like the Neanderthals, were replaced during one of our species' multiple expansions.

What I have tried to explain in the preceding chapters is how culture-gene coevolution gave rise to the impressive list above.

Thus, the key to understanding our uniqueness lies in understanding the process, not in emphasizing the specific products of that process—language, collaboration, tools, and so on.

We will parachute both primate teams into a remote tropical forest in Central Africa.

And then we'll come back in two years and count the survivors from each team.

The team with more survivors wins.

Of course, no team will be allowed to take the equipment.

No matches, no water jugs, no knives, no shoes, no glasses, no antibiotics, no pots, no guns, no ropes.

(…) Let’s face it.

There is a high probability that the human team you are in will be defeated.

Whether your team has big brains and a lot of ego or not, you're probably going to lose badly to a bunch of monkeys.

If our large brains were useless for survival as hunter-gatherers in Africa, the continent where our species evolved, what purpose were they serving? How did we manage to expand into all the diverse environments across the globe?

---From "Chapter 1: The Mysterious Primate"

Our species' uniqueness, and its resulting ecological dominance, stems from the way cultural evolution has often worked over hundreds or even thousands of years, allowing us to assemble cultural adaptations.

The cultural adaptations I have highlighted in the above examples are tools and know-how for finding and processing food, locating water, cooking, and moving around.

But as you read this book, it will become clear that cultural adaptations include not only the things we can create, but also the way we think and the things we like.

---From "Chapter 3: Can You Survive If You Were Dropped on a Deserted Island?"

Natural selection has shaped us into a cultural species by altering our development in many ways.

(1) By shortening infancy and lengthening childhood, the body's growth was slowed down, but a growth spurt was added during adolescence.

(2) It has altered neural development in complex ways that allow our brains to be ahead of their time, yet still be able to expand rapidly and maintain plasticity.

Going forward, how our rapid genetic evolution, large adult brains, slow physical development, and progressive wiring become possible will be considered only as part of a larger set of characteristics.

These characteristics of our species, including the sexual division of labor, intensive parental investment, and the long post-reproductive period we associate with menopause, likely interact with cultural evolution in a number of crucial ways.

---From "Chapter 5: Culture Has Made Our Bodies Weak"

Ciguatera toxin is produced by certain marine microorganisms that thrive on dead coral reefs.

The poison accumulates as it moves up the food chain, reaching dangerous levels in some large, long-lived fish, including the species mentioned above.

Acute symptoms of poisoning that last about a week include diarrhea, vomiting, headache, itching, and a unique sensation of hot and cold sensations on the skin.

(…) Like other toxins, ciguatera probably accumulates in breast milk and could endanger nursing infants.

In adults, ciguerra poisoning has a low rate of death.

(…) This set of taboos constitutes a kind of cultural adaptation that selectively targets the most toxic species in women's regular diet, precisely at the time when mothers and children are most vulnerable.

To explore how this cultural adaptation emerged, we studied how women acquired these taboos and what kind of causal understandings they had.

During adolescence and young adulthood, we first learn these taboos from our mothers, mothers-in-law, and grandmothers.

---From “Chapter 7: On the Origin of Trust”

Amazingly, we can even speculate about the ancient brains of our ancestors, dating back roughly two million years ago.

Analysis of Oldowan tools suggests that 90 percent of their makers were right-handed.

This is unusual, as apes have no hand preference, and we have a dominant hand because the two hemispheres of our brains share the same role.

Typically, the human left brain focuses on language and tool use.

Consistent with this, the early Homo skull tentatively suggests expansions in areas known to be important for language, gesture, and tool use, and shows the emergence of a physical separation between the two hemispheres.

Consistent with the presence of tools and the culturally driven response to the synergy between tools for food processing and tools for communication, it seems likely that the neural division of labor that characterizes the modern human brain has already begun to emerge.

---From "Chapter 15: The Threshold of Evolution"

The answer to the question, 'Why are humans different?' is, 'We have crossed the Rubicon.'

Cultural evolution was cumulative, and then both this accumulating mass of information and its cultural products, like fire and food-sharing norms, developed into central driving forces in human genetic evolution.

The reason we appear so unique is that no other living animal has trodden this path, and those who have, like the Neanderthals, were replaced during one of our species' multiple expansions.

What I have tried to explain in the preceding chapters is how culture-gene coevolution gave rise to the impressive list above.

Thus, the key to understanding our uniqueness lies in understanding the process, not in emphasizing the specific products of that process—language, collaboration, tools, and so on.

---From "Chapter 17: New Animals Created by Cultural Evolution"

Publisher's Review

★ Includes a special recommendation from Professor Jeong Jae-seung! ★

★ Selected for the KAIST Convergence Talent Department Reading List! ★

★ Highly recommended by world-renowned scholars Darren Acemoglu, Jonathan Haidt, and James Robinson ★

★ A hot topic from the best-selling author of "Weird"! ★

A bold book that directly challenges Steven Pinker, Jared Diamond, and Richard Dawkins.

A shocking book that changed the paradigm of human evolution!

“The single most notable book in academia recently.

“This is a masterpiece that you will want to keep on your bookshelf and read at any time to answer the question, ‘Who are we?’”

_(Jeong Jae-seung, Professor, Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences and School of Convergence Talent, KAIST)

The evolutionary history of our species, Homo sapiens, is one of the most fascinating stories in human history.

How, in this vast history, did the genus Homo, living in such a small group, evolve into a world-dominating intelligence? And what is it that makes our species so special?

Biological anthropologists have explained our evolution through the hypotheses of natural selection and sexual selection.

But this approach simply makes us think of ourselves as clever chimpanzees.

Professor Joseph Henrik of Harvard University's Department of Human Evolutionary Biology offers a new understanding and persuasive power of human evolution and success through various research data and case studies that subvert existing hypotheses and prove counterintuitive ideas.

While Jared Diamond's Guns, Germs, and Steel argues that geographical conditions and nature have influenced human civilization, Homo Sapiens emphasizes the influence of culture, institutions, and norms on human evolution.

Culture has evolved alongside our species, and culture and genes have evolved in interaction.

This concept of coevolution has transformed our understanding and opened up new horizons, suggesting that human evolution is not simply dependent on genetic change, but is also rooted in cultural development and cooperation.

The emergence of new animals created by cultural evolution!

“Culture” is a biological characteristic that supports humans.

We have the ability to create the tools, techniques, and organizational forms necessary to adapt to and thrive in diverse environments.

So, did our species survive because we were more intelligent than other species? The inference that the intelligence derived from our large brains shaped the modern human species is quite plausible.

Although we are an intelligent species, we are by no means clever enough to explain our species' ecological dominance.

Esther Hermann and Michael Tomasello of the Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, administered 38 cognitive tests to 106 chimpanzees, 105 German children, and 32 orangutans.

On tests measuring spatial, quantitative, and causal abilities, children as young as two and a half years old are no different from chimpanzees, whose brains are smaller than ours.

Even in tool use, chimpanzees easily outperformed human children, with a 74% correct response rate compared to 23% for the chimpanzees.

Ultimately, intelligence does not explain ecological dominance or the uniqueness of our species.

At this point, the hypothesis that humans survived because they were smart loses its power.

However, in this experiment, there was one thing that the human child was far superior to.

It is ‘social learning’.

Social learning refers to any situation in which an individual's learning is influenced by another individual, and involves many different types of psychological processes.

From infancy, we are adaptive learners who carefully choose when, what, and from whom we learn.

Culture became cumulative as members of our evolutionary lineage began to learn from each other in some way.

These new products of cultural evolution—fire, cooking and cutting tools, clothing, simple body language, javelins, water containers—served as major sources of selective pressure, genetically shaping our minds and bodies.

Driven by this interplay between culture and genes, or culture-gene coevolution, our species has evolved along a novel evolutionary path not observed elsewhere in nature, becoming a very different, new kind of animal.

A book that pierces the question, 'What is a human being?'

Where will humanity go in the future after crossing the threshold of evolution?

We play chess, read books, cook, create institutions, create religions, and even make fun of people who dress or speak differently.

And while all societies follow rules, cooperate on a large scale, and communicate using complex language, the ways and degrees to which they do all this vary greatly.

How could evolution produce such life forms, and where is it leading us? How can answering these questions help us understand human psychology and behavior?

The key to understanding why humans are so different from other animals is to realize that we are a 'cultural species'.

Trying to understand the evolution of human anatomy, physiology, and psychology without considering cultural-genetic coevolution is like studying the evolution of fish while ignoring the fact that fish evolved while living in water.

The moment we fully grasp this truth, the way we think about the intersection of culture, genes, biology, institutions, and history, and the way we approach human behavior and psychology, will be completely transformed.

So, does this mark the final chapter of our evolutionary history? Of course not.

Innovation in our species comes not from a single genius, but from the interconnected minds and the flow and recombination of ideas, practices, lucky errors, and serendipitous insights over generations.

The potential for this innovation, coupled with the proliferation of the Internet, is dramatically expanding our collective brainpower.

Therefore, to advance the quest to better understand human life, we need to embrace a new kind of evolutionary science that focuses on the rich interactions and coevolution of psychology, culture, biology, history, and genes.

By following Professor Joseph Henrik's expansive and fascinating journey, we will explore how culture has shaped the course of human evolution and where it is taking us. This journey will shed light on how to understand human life and society today and offer insights into countless challenges.

★ Selected for the KAIST Convergence Talent Department Reading List! ★

★ Highly recommended by world-renowned scholars Darren Acemoglu, Jonathan Haidt, and James Robinson ★

★ A hot topic from the best-selling author of "Weird"! ★

A bold book that directly challenges Steven Pinker, Jared Diamond, and Richard Dawkins.

A shocking book that changed the paradigm of human evolution!

“The single most notable book in academia recently.

“This is a masterpiece that you will want to keep on your bookshelf and read at any time to answer the question, ‘Who are we?’”

_(Jeong Jae-seung, Professor, Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences and School of Convergence Talent, KAIST)

The evolutionary history of our species, Homo sapiens, is one of the most fascinating stories in human history.

How, in this vast history, did the genus Homo, living in such a small group, evolve into a world-dominating intelligence? And what is it that makes our species so special?

Biological anthropologists have explained our evolution through the hypotheses of natural selection and sexual selection.

But this approach simply makes us think of ourselves as clever chimpanzees.

Professor Joseph Henrik of Harvard University's Department of Human Evolutionary Biology offers a new understanding and persuasive power of human evolution and success through various research data and case studies that subvert existing hypotheses and prove counterintuitive ideas.

While Jared Diamond's Guns, Germs, and Steel argues that geographical conditions and nature have influenced human civilization, Homo Sapiens emphasizes the influence of culture, institutions, and norms on human evolution.

Culture has evolved alongside our species, and culture and genes have evolved in interaction.

This concept of coevolution has transformed our understanding and opened up new horizons, suggesting that human evolution is not simply dependent on genetic change, but is also rooted in cultural development and cooperation.

The emergence of new animals created by cultural evolution!

“Culture” is a biological characteristic that supports humans.

We have the ability to create the tools, techniques, and organizational forms necessary to adapt to and thrive in diverse environments.

So, did our species survive because we were more intelligent than other species? The inference that the intelligence derived from our large brains shaped the modern human species is quite plausible.

Although we are an intelligent species, we are by no means clever enough to explain our species' ecological dominance.

Esther Hermann and Michael Tomasello of the Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, administered 38 cognitive tests to 106 chimpanzees, 105 German children, and 32 orangutans.

On tests measuring spatial, quantitative, and causal abilities, children as young as two and a half years old are no different from chimpanzees, whose brains are smaller than ours.

Even in tool use, chimpanzees easily outperformed human children, with a 74% correct response rate compared to 23% for the chimpanzees.

Ultimately, intelligence does not explain ecological dominance or the uniqueness of our species.

At this point, the hypothesis that humans survived because they were smart loses its power.

However, in this experiment, there was one thing that the human child was far superior to.

It is ‘social learning’.

Social learning refers to any situation in which an individual's learning is influenced by another individual, and involves many different types of psychological processes.

From infancy, we are adaptive learners who carefully choose when, what, and from whom we learn.

Culture became cumulative as members of our evolutionary lineage began to learn from each other in some way.

These new products of cultural evolution—fire, cooking and cutting tools, clothing, simple body language, javelins, water containers—served as major sources of selective pressure, genetically shaping our minds and bodies.

Driven by this interplay between culture and genes, or culture-gene coevolution, our species has evolved along a novel evolutionary path not observed elsewhere in nature, becoming a very different, new kind of animal.

A book that pierces the question, 'What is a human being?'

Where will humanity go in the future after crossing the threshold of evolution?

We play chess, read books, cook, create institutions, create religions, and even make fun of people who dress or speak differently.

And while all societies follow rules, cooperate on a large scale, and communicate using complex language, the ways and degrees to which they do all this vary greatly.

How could evolution produce such life forms, and where is it leading us? How can answering these questions help us understand human psychology and behavior?

The key to understanding why humans are so different from other animals is to realize that we are a 'cultural species'.

Trying to understand the evolution of human anatomy, physiology, and psychology without considering cultural-genetic coevolution is like studying the evolution of fish while ignoring the fact that fish evolved while living in water.

The moment we fully grasp this truth, the way we think about the intersection of culture, genes, biology, institutions, and history, and the way we approach human behavior and psychology, will be completely transformed.

So, does this mark the final chapter of our evolutionary history? Of course not.

Innovation in our species comes not from a single genius, but from the interconnected minds and the flow and recombination of ideas, practices, lucky errors, and serendipitous insights over generations.

The potential for this innovation, coupled with the proliferation of the Internet, is dramatically expanding our collective brainpower.

Therefore, to advance the quest to better understand human life, we need to embrace a new kind of evolutionary science that focuses on the rich interactions and coevolution of psychology, culture, biology, history, and genes.

By following Professor Joseph Henrik's expansive and fascinating journey, we will explore how culture has shaped the course of human evolution and where it is taking us. This journey will shed light on how to understand human life and society today and offer insights into countless challenges.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: May 27, 2024

- Page count, weight, size: 616 pages | 152*225*35mm

- ISBN13: 9791171175840

- ISBN10: 1171175841

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)