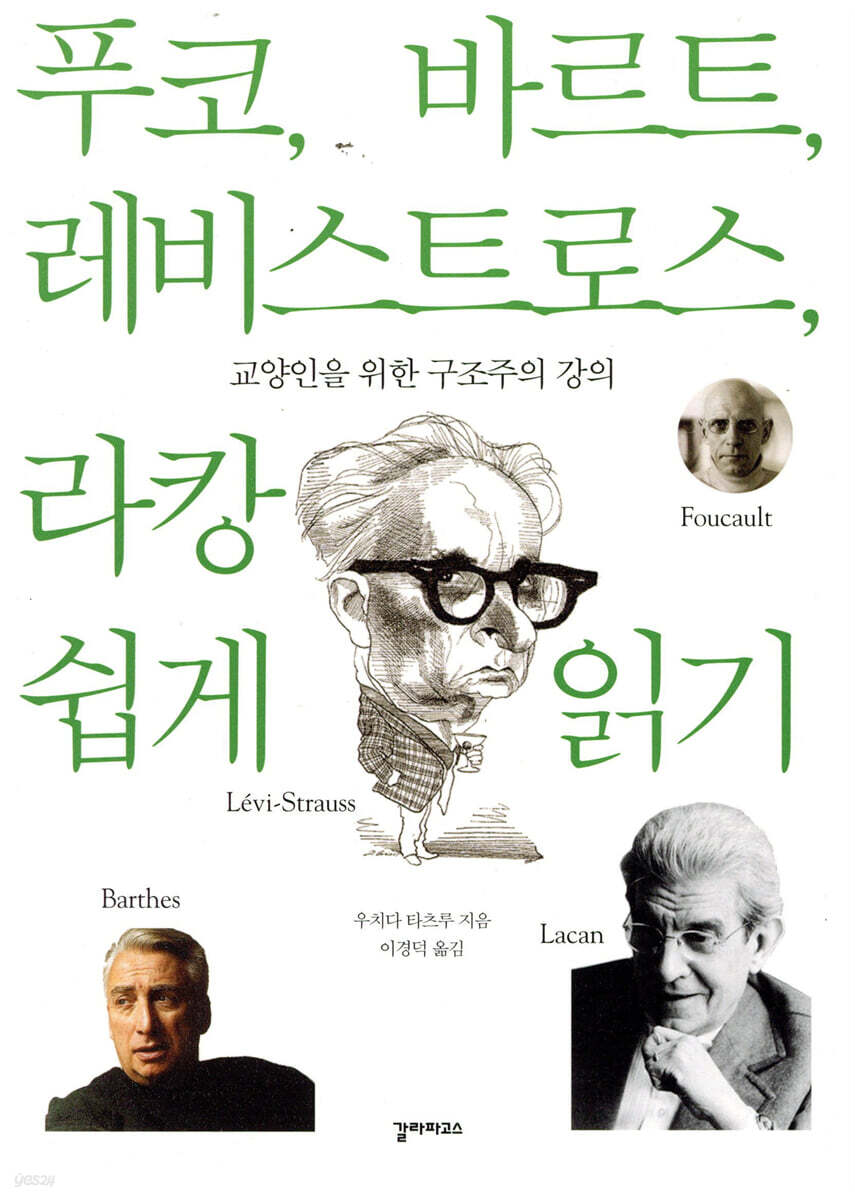

Easy Reading of Foucault, Barthes, Levi-Strauss, and Lacan

|

Description

Book Introduction

From Marx, Freud, and Nietzsche to Saussure, Foucault, Barthes, Levi-Strauss, and Lacan!

Meet the representative figures and core ideas of structuralism in one place!

This book is an excellent commentary on structuralism, beginning with the question, "What is structuralism?" and tracing its origins, history, and content. It also brings together leading figures in structuralism and summarizes their core ideas so that they can be seen at a glance.

This book fully demonstrates the author's talent for explaining difficult ideas and concepts in an easy-to-understand way. It is the best introductory book on structuralism that can be easily and enjoyably read by both those studying structuralism and the general public who want to know more about structuralism.

As the translator says, “The reason we should be interested in structuralism is, as is the essence of all learning, to live better and be happier,” this book contains more than just “textbook” information, allowing us to reflect on the current significance of structuralism through the human side of it that is not easily seen in other books.

Is structuralism still relevant in this day and age? The answer this book presents is a resounding yes.

The authors answer that the voice of structuralism, which encourages us to shake off arrogance and prejudice and recognize ourselves within a diverse world, is what is most needed in this age of rampant "absence of communication."

Knowing the nature of structuralism and understanding it closely will be the most important first step toward understanding my current life and building a better tomorrow and a more advanced society.

Meet the representative figures and core ideas of structuralism in one place!

This book is an excellent commentary on structuralism, beginning with the question, "What is structuralism?" and tracing its origins, history, and content. It also brings together leading figures in structuralism and summarizes their core ideas so that they can be seen at a glance.

This book fully demonstrates the author's talent for explaining difficult ideas and concepts in an easy-to-understand way. It is the best introductory book on structuralism that can be easily and enjoyably read by both those studying structuralism and the general public who want to know more about structuralism.

As the translator says, “The reason we should be interested in structuralism is, as is the essence of all learning, to live better and be happier,” this book contains more than just “textbook” information, allowing us to reflect on the current significance of structuralism through the human side of it that is not easily seen in other books.

Is structuralism still relevant in this day and age? The answer this book presents is a resounding yes.

The authors answer that the voice of structuralism, which encourages us to shake off arrogance and prejudice and recognize ourselves within a diverse world, is what is most needed in this age of rampant "absence of communication."

Knowing the nature of structuralism and understanding it closely will be the most important first step toward understanding my current life and building a better tomorrow and a more advanced society.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Introduction

Chapter 1: Pre-structuralist History

We live in an 'age of prejudice'

A view of the world

Marx's heliocentric view of humanity

Freud discovered the 'room of the unconscious'

Nietzsche criticized 'judgment based on conjecture'

Chapter 2: The Emergence of Saussure, the Founder

Language is not the 'name of things'

Experience is defined by language

We speak the language of others

Chapter 3: Foucault and Genealogical Thinking

History is not directed towards 'now, here, and me'

Who affirms madness?

The body is a social institution

The King's Two Bodies

The state manipulates the body

Why do people want to talk about sex?

Chapter 4: Barthes and the Leadership of Writing

'Objective language use' reigns supreme

The Birth of the Reader and the Death of the Author

The impossible dream of 'pure language'

Chapter 5: Levi-Strauss and the Never-ending Gift

The Age of Structuralism Begins

The debate between Sartre and Camus

The 'crushed' Sartre

What is phonology?

All kinship relationships are represented by 2 bits

Human nature lies in 'giving'

Chapter 6: Lacan and Analytical Dialogue

The infant grasps 'me' through the mirror.

Memory is not the 'truth of the past'

Becoming an adult

Communication is what matters

Words that come out

Translator's Note

References

Chapter 1: Pre-structuralist History

We live in an 'age of prejudice'

A view of the world

Marx's heliocentric view of humanity

Freud discovered the 'room of the unconscious'

Nietzsche criticized 'judgment based on conjecture'

Chapter 2: The Emergence of Saussure, the Founder

Language is not the 'name of things'

Experience is defined by language

We speak the language of others

Chapter 3: Foucault and Genealogical Thinking

History is not directed towards 'now, here, and me'

Who affirms madness?

The body is a social institution

The King's Two Bodies

The state manipulates the body

Why do people want to talk about sex?

Chapter 4: Barthes and the Leadership of Writing

'Objective language use' reigns supreme

The Birth of the Reader and the Death of the Author

The impossible dream of 'pure language'

Chapter 5: Levi-Strauss and the Never-ending Gift

The Age of Structuralism Begins

The debate between Sartre and Camus

The 'crushed' Sartre

What is phonology?

All kinship relationships are represented by 2 bits

Human nature lies in 'giving'

Chapter 6: Lacan and Analytical Dialogue

The infant grasps 'me' through the mirror.

Memory is not the 'truth of the past'

Becoming an adult

Communication is what matters

Words that come out

Translator's Note

References

Into the book

Structuralism, simply put, is a way of thinking that:

“We always belong to a certain era, a certain region, a certain social group, and these conditions fundamentally determine our views, the way we feel, and the way we think.

So we are not living as freely or as autonomously as we think.

Rather, in most cases, we tend to selectively 'see, feel, or think' only what the social group we belong to accepts.

And what the group unconsciously excludes will never enter our sight in the first place, will never collide with our sensibilities, or become the subject of our reflections.” The achievement of structuralism is that it thoroughly investigated the fact that, although we believe that we are ‘autonomous subjects’ who judge and act for ourselves, in fact, that freedom or autonomy is quite limited. ---pp.

27-28

The theory taught by a linguist (Saussure) in a small classroom at the University of Geneva in the early 20th century was later inherited by the Prague School, and formed a vein of thought through a heterogeneous mix with various literary and ideological movements.

And structuralism emerged in the midst of this new wave of academic knowledge that was prominent in Eastern Europe and Russia in the 1920s and 1930s.

The French post-war generation from the 1940s to the 1960s, who were baptized by this new wave, corresponds to the 'third generation' of structuralism.

By these people (Foucault, Barthes, Lévi-Strauss, Lacan), structuralist theory, which had been limited to linguistics until then, was suddenly expanded into various adjacent fields and soon acquired a universal intellectual status.----pp.

81-82

What is important when reading Foucault's social history is that (……) he does not understand the word 'power' as a simple entity such as 'state power' or the various 'ideological devices' it controls.

'Power' has an 'accumulation tendency' that seeks to classify, name, and standardize all levels of human activity and register them in the public cultural inventory.

Therefore, even if it is called a critique of power, (……) insofar as it is actually listed and cataloged and given a place to view it at a glance, it has already turned into ‘power’.

(……) What Foucault pointed out is that all activities of knowledge necessarily function as ‘power’ insofar as they are driven by the desire to organize and ‘accumulate’ information about the formation of the world or the appearance of humans. ---pp.

120-121

What Barthes explored was the impossible dream of a "pure écriture, freed from any slavish submission to the order imprinted by grammar," a pure language that asserts nothing, denies nothing, and simply stands there.

(……) The leadership of écriture, pure écriture, refers to a ‘pure white’ écriture in which there is no subjective intervention of the speaker, such as hope, prohibition, command, or judgment.

This was the dream of language that Barthes pursued throughout his life. ---pp.

146-147

Levi-Strauss's conclusion was that the difference between 'savage thinking' and 'civilized thinking' was not a difference in stage of development, but rather a 'different thinking' from the beginning, and that comparing them to determine which was superior was meaningless.

(……) ‘Civilized people’ and ‘savages’ just have different ways of having interests, but the fact that ‘savages’ do not see the world like ‘civilized people’ does not mean that they are intellectually inferior.

(……) Levi-Strauss starts from this premise.

And he sternly cautions that 'every civilization has an overestimation of the objective aspects of its own thinking.'

(……) The more people think they are ‘civilized’ and have an ‘objective’ view of the structure of the world, the more likely they are to make this mistake.

(……) Levi-Strauss does not allow such arrogance of ‘civilized people’.

---pp.

160-162

According to Lacan, humans become “normal adults” after experiencing two major “frauds” in their lives.

The first is to gain the foundation of 'I' by thinking of 'what is not me' as 'I' in the mirror stage, and the second is to 'explain' one's powerlessness and incompetence as a result of the threatening intervention of the 'father' through the Oedipus stage.

(……) Therefore, psychoanalytic treatment is usually conducted with analysands who have failed to pass the Oedipus stage, and the work is standardly carried out by assuming the analyst as the ‘father’ and sharing ‘the story about oneself’ with the ‘father’ and receiving approval from the ‘father’.

(……) This ‘talking and responding’ is the true driving force of analytical conversation.

(……) Reactivating stagnant communication by ‘sharing stories’ is a strategy that we always employ when pursuing the possibility of human ‘symbiosis’ with others, not just in psychoanalysis.---pp.

213-215

I've been wanting to write an introductory book on structuralism for a while now.

(……) While suffering in the world, I gradually came to know what ‘things that are precious to humans’ are.

After so many years, I read the book again, and the things that structuralism and the structuralists were trying to say, which were so difficult to understand and so difficult to understand that I thought they were evil, began to come into clearer focus.

In short, I came to know that Levi-Strauss said, "Let's all live together in harmony," Barthes said, "The use of language determines a person," Lacan said, "Be an adult," and Foucault said, "I hate fools."

“We always belong to a certain era, a certain region, a certain social group, and these conditions fundamentally determine our views, the way we feel, and the way we think.

So we are not living as freely or as autonomously as we think.

Rather, in most cases, we tend to selectively 'see, feel, or think' only what the social group we belong to accepts.

And what the group unconsciously excludes will never enter our sight in the first place, will never collide with our sensibilities, or become the subject of our reflections.” The achievement of structuralism is that it thoroughly investigated the fact that, although we believe that we are ‘autonomous subjects’ who judge and act for ourselves, in fact, that freedom or autonomy is quite limited. ---pp.

27-28

The theory taught by a linguist (Saussure) in a small classroom at the University of Geneva in the early 20th century was later inherited by the Prague School, and formed a vein of thought through a heterogeneous mix with various literary and ideological movements.

And structuralism emerged in the midst of this new wave of academic knowledge that was prominent in Eastern Europe and Russia in the 1920s and 1930s.

The French post-war generation from the 1940s to the 1960s, who were baptized by this new wave, corresponds to the 'third generation' of structuralism.

By these people (Foucault, Barthes, Lévi-Strauss, Lacan), structuralist theory, which had been limited to linguistics until then, was suddenly expanded into various adjacent fields and soon acquired a universal intellectual status.----pp.

81-82

What is important when reading Foucault's social history is that (……) he does not understand the word 'power' as a simple entity such as 'state power' or the various 'ideological devices' it controls.

'Power' has an 'accumulation tendency' that seeks to classify, name, and standardize all levels of human activity and register them in the public cultural inventory.

Therefore, even if it is called a critique of power, (……) insofar as it is actually listed and cataloged and given a place to view it at a glance, it has already turned into ‘power’.

(……) What Foucault pointed out is that all activities of knowledge necessarily function as ‘power’ insofar as they are driven by the desire to organize and ‘accumulate’ information about the formation of the world or the appearance of humans. ---pp.

120-121

What Barthes explored was the impossible dream of a "pure écriture, freed from any slavish submission to the order imprinted by grammar," a pure language that asserts nothing, denies nothing, and simply stands there.

(……) The leadership of écriture, pure écriture, refers to a ‘pure white’ écriture in which there is no subjective intervention of the speaker, such as hope, prohibition, command, or judgment.

This was the dream of language that Barthes pursued throughout his life. ---pp.

146-147

Levi-Strauss's conclusion was that the difference between 'savage thinking' and 'civilized thinking' was not a difference in stage of development, but rather a 'different thinking' from the beginning, and that comparing them to determine which was superior was meaningless.

(……) ‘Civilized people’ and ‘savages’ just have different ways of having interests, but the fact that ‘savages’ do not see the world like ‘civilized people’ does not mean that they are intellectually inferior.

(……) Levi-Strauss starts from this premise.

And he sternly cautions that 'every civilization has an overestimation of the objective aspects of its own thinking.'

(……) The more people think they are ‘civilized’ and have an ‘objective’ view of the structure of the world, the more likely they are to make this mistake.

(……) Levi-Strauss does not allow such arrogance of ‘civilized people’.

---pp.

160-162

According to Lacan, humans become “normal adults” after experiencing two major “frauds” in their lives.

The first is to gain the foundation of 'I' by thinking of 'what is not me' as 'I' in the mirror stage, and the second is to 'explain' one's powerlessness and incompetence as a result of the threatening intervention of the 'father' through the Oedipus stage.

(……) Therefore, psychoanalytic treatment is usually conducted with analysands who have failed to pass the Oedipus stage, and the work is standardly carried out by assuming the analyst as the ‘father’ and sharing ‘the story about oneself’ with the ‘father’ and receiving approval from the ‘father’.

(……) This ‘talking and responding’ is the true driving force of analytical conversation.

(……) Reactivating stagnant communication by ‘sharing stories’ is a strategy that we always employ when pursuing the possibility of human ‘symbiosis’ with others, not just in psychoanalysis.---pp.

213-215

I've been wanting to write an introductory book on structuralism for a while now.

(……) While suffering in the world, I gradually came to know what ‘things that are precious to humans’ are.

After so many years, I read the book again, and the things that structuralism and the structuralists were trying to say, which were so difficult to understand and so difficult to understand that I thought they were evil, began to come into clearer focus.

In short, I came to know that Levi-Strauss said, "Let's all live together in harmony," Barthes said, "The use of language determines a person," Lacan said, "Be an adult," and Foucault said, "I hate fools."

---pp.

216-217

216-217

Publisher's Review

Since its publication in 2002, it has been reprinted many times.

It has never fallen from its position as a bestseller.

The best introduction to structuralism!

『Easy Reading of Foucault, Barthes, Levi-Strauss, and Lacan - Structuralism Lectures for the Cultured』 is a book that provides an overview of structuralism as a whole, focusing on the so-called "Four Musketeers of Structuralism": Foucault, Barthes, Levi-Strauss, and Lacan.

Although there are already many works on structuralism, the appearance of this book is welcome, as it is difficult to find an easily readable one.

Professor Tatsuro Uchida, the author, demonstrates his forte in explaining difficult ideas and theories in an easy-to-understand way, neatly organizing the definition of structuralism, its origins and history, and its representative figures and ideas in a way that is easy to understand at a glance.

In short, this book is an excellent introduction to structuralism that will be useful to both those studying structuralism and general readers interested in structuralism.

Chapter 1, "Pre-structuralism History," examines the core ideas of Marx, Freud, and Nietzsche, who laid the foundation for structuralism before the full-fledged structuralist era began. Chapter 2, "The Emergence of Saussure, the Founder," examines Saussure's structuralist linguistics, which ushered in the era of structuralism.

In "Chapter 3: Foucault and Genealogical Thinking," we examine the social history work of Foucault, the first of the "Four Musketeers of Structuralism," and in "Chapter 4: Barthes and the Leadership of Writing," we examine the core ideas of Barthes, the second of the "Four Musketeers of Structuralism," who made a significant contribution to critical theory.

In "Chapter 5, Levi-Strauss and the Never-ending Gift," we will encounter the structuralist anthropology of Levi-Strauss, the third of the "Four Musketeers," the greatest cultural anthropologist of the 20th century. In the final chapter, "Chapter 6, Lacan and Analytical Dialogue," we will learn about the psychoanalysis of Lacan, the last of the "Four Musketeers."

As the translator says, “The reason we should be interested in structuralism is, as is the essence of all learning, to live better and be happier,” this book contains more than just “textbook” information, allowing us to look back on the current significance of structuralism through its human aspects that are not easily seen in other books.

Are humans 'autonomous subjects'?

What is structuralism? Professor Uchida defines it in one word in the introduction to this book: a way of thinking.

“We always belong to a certain era and a certain social group, and those conditions fundamentally determine our views, how we feel, and how we think.

So we are not living as freely or as autonomously as we think.

Rather, in most cases, we tend to selectively see, feel, or think only what is accepted by the social group to which we belong.

“What the group unconsciously excludes will never enter our sight, will never clash with our sensibilities, and will never become the subject of our reflections.” (p.

27)

The author's explanation is clear.

In short, we believe that we are “autonomous subjects” who make our own judgments and actions, but in fact, that freedom and autonomy are extremely limited.

This is the core of structuralism discussed throughout this book.

So where did this kind of thinking originate? To understand the origins of structuralism, the author first explores the question, "Is there truly such a thing as objectivity in our thinking and judgment?" By bringing together three controversial figures who have had a profound impact on later generations,

Just the names alone are impressive: Marx, Freud, and Nietzsche.

In Chapter 1, "Pre-structuralism History," we encounter these historical figures who laid the foundations of structuralism before the full-fledged structuralist era began.

Laying the groundwork for structuralism

Marx spent his entire life deeply delving into the question, "What special conditions are responsible for the formation of human thought and judgment?"

Accordingly, he focused on “class” as a factor that plays an important role in the historical change of social groups.

In other words, “the individuality of a human being is determined not by ‘who he is’ but by ‘what he does.’”

The fact that the origin of subjectivity lies not in the subject's 'existence' but in the subject's 'action' is the most fundamental concept of structuralism and an important idea shared by all structuralists.

For this reason, Marx is pointed out as the most decisive contributor who laid the foundation for the later era of structuralism.

Freud, on the other hand, focused on the innermost realm of human beings.

He believed that “human thoughts and actions are governed by mental activities that humans cannot directly perceive.”

Something that one may not be aware of, but nevertheless governs one's actions and judgments.

The 'unconscious' was born.

Among those who lived in the same era as these people, there was another person who argued that “human thought is not free,” and that person was Friedrich Nietzsche.

Nietzsche argued that “humans are, for the most part, nothing more than slaves to external norms,” and that “what we take for granted” are in fact “prejudices peculiar to a certain age or region.”

His statement that “we can never be ‘knowers’ of ourselves” is quite significant.

This book shows that their thoughts have a deep “common ground”: that “humans are not the protagonists of their own mental lives.”

“Marx saw that humans appear to think freely, but in reality they think in terms of classes,” “Freud saw that humans appear to think freely, but in reality they think without knowing ‘through what process’ they are thinking,” and Nietzsche saw that humans are beings who change according to their external environment.

Although it is difficult to see structuralism as directly expressed in their thoughts, it is clear that they played a key role in leveling the ground for structuralism.

Saussure ushered in the era of structuralism.

So who truly ushered in the era of structuralism? "Around the same time that Freud was lecturing on psychoanalysis in Vienna," at the University of Geneva in Switzerland, "a linguist was giving a 'lecture on general linguistics' to a small group of linguists and linguistics students."

Ferdinand de Saussure.

He is the person who is evaluated as having started structuralism in the history of thought.

In Chapter 2, "The Emergence of Saussure, the Founder," we observe the process of the prelude to the era of structuralism opening through the core content of Saussure's thought.

The author cites Saussure's linguistics as "the most important view that structuralism received": "Language is not 'the name of things.'"

Following the traditional view of language since Greece, language has been recognized as the name of things, but Saussure did not agree with that.

In his theory, he taught that “names of things are given arbitrarily by human beings” and that things and their names are not “connected by any special necessity.”

He also argued that “the nature, meaning, and function of something are later determined by what ‘position’ it occupies within the network or system that includes it.”

But at the same time, Saussure reminded us that “as long as we use language, we always endorse and reinforce the values of the linguistic community to which we belong.”

In other words, 'what is being said inside me when I speak' is mostly 'the words of others' who belong to the same community.

Therefore, the author argues that if “when I speak,’ the words are bound by the rules of the Korean language and consist of prescribed vocabulary,” then “most of what we ‘say’ is obtained from others, and then it would be shameful to say ‘I speak.’”

The obvious fact that the origins of what I say are actually mostly outside of me comes from Saussure.

This theory, “taught by a single linguist in a small classroom at the University of Geneva in the early 20th century,” has since developed into various schools and fields.

The prelude to structuralism began in such an exciting way.

Foucault, in search of the origin of the 'I'

This book classifies the post-war French generation, who were baptized in this new way of thinking, from Saussure through the Prague School, as the 'third generation' of structuralism, and its representative figures are Michel Foucault in the field of social history, Roland Barthes in semiotics, Lévi-Strauss in anthropology, and Lacan in psychoanalysis.

The author calls them the so-called 'Four Musketeers', the most important of structuralism, and devotes a significant portion of the book to explaining their ideas.

In Chapter 3 of this book, “Foucault and Genealogical Thinking,” we examine an outline of Foucault’s thought.

We often forget that “every civilization has its own birth date, and we can only know what it is by understanding the context of its own history leading to its birth.”

And there are countless cases where people arbitrarily think, “What I am seeing is something that has always existed, and the society I live in has always been like this.”

Foucault devoted himself steadfastly to his research with the goal of “destroying these foolish beliefs” of human beings.

In many of his representative works, such as 『Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison』, 『A History of Madness』, and 『The Archaeology of Knowledge』, he explores the true origins of things.

“Whether it be ‘prison,’ ‘madness,’ or ‘academics,’ we all mistakenly believe that it is fundamentally the same everywhere and at all times, regardless of era or region.”

“However, all social institutions existing in human society were born at some point in the past as a complex effect of several historical facts and did not exist before that time.”

“Foucault’s ‘social history’ work is to point out this extremely obvious (but easily forgotten) fact and to go back to the site where the system or meaning was created.”

“What kind of history did this ‘I’ here go through to form?” This book shows that asking this question is the core of the ‘critical structure’ that Foucault advocated.

However, the author confesses that this is actually a limited hope, like “wanting to see the back of one’s own head with one’s own eyes.”

Perhaps it is because Foucault gave his all to that impossible task that his life and thoughts are all the more moving to us.

Barthes, 'The author is dead.'

Barth's views are very diverse, and in Chapter 4, Barth and the Leadership of Writing, this book examines the core of Barth's thought, particularly the concept of 'écriture' and the 'death of the author.'

As Saussure pointed out, “our modes of thought and experience depend so much on the language we use that when the language we use changes, our modes of thought and experience also change.”

That is, even when we believe we are using our native language freely, “language operates according to some invisible rules that we are not aware of.”

These rules are 'language' and 'still'.

Langue is a “regulation from the outside,” that is, “a set of rules and habits shared by all writers of a given era,” while still is our personal sense of language that “regulates our language use ‘from the inside’” when we speak.

And in addition to these, there is a third element that regulates our use of language: 'écriture'.

According to Barthes, écriture is a “‘preference’ that is collectively chosen and practiced,” which signifies the choice of “the social field that the writer must assign to his ‘natural’ language.”

This concept has influenced the recognition of the existence of a “‘intertwined’ structure” between grammar and human society, or between text and reader, and has presented this as a “basic principle of criticism.”

Barth also denied the principle of modern criticism that views the author as someone who creates from nothing.

A ‘text’ is a kind of ‘fabric’, and ‘many things are needed’ to create a single piece of text, and this ‘fabric’, which is filled with various elements from various places through various processes, cannot be said to have been completed by a single person.

This is the 'death of the author'.

His new concept signaled that the era in which the modern concept of 'author' was in common use had already passed, and that the birth of the reader required the "death of the author."

Barthes's attitude of finding "joy" in the "movement of text creation" itself, regardless of the "fame, profit, or power" that "copyright" brings, leaves much food for thought, especially for modern people living in the Internet age.

Levi-Strauss, breaking down the boundaries between 'barbarism' and 'civilization'

Following Foucault and Barthes, Chapter 5 of this book, “Levi-Strauss and the Never-ending Gift,” introduces the ideas of Lévi-Strauss, the greatest cultural anthropologist of the 20th century.

Levi-Strauss is a pioneer of structuralist anthropology who surprised the world with his bold approach of “interpreting kinship structure as a theoretical model of phonology.”

Influenced by Roman Jakobson of the Prague School, a direct descendant of Saussure, he combined linguistics with the analytical methods of anthropology to reconstruct 'uncivilized society' into 'another civilized society.'

In short, 'civilized people' and 'savages' only have different ways of taking interest in things, but the fact that 'savages' do not see the world like 'civilized people' does not mean that they are intellectually inferior.

His contemporaries were astonished to see his theory, based on extensive fieldwork, “crushing Sartre’s existentialism, ‘fully armed’ with Marxism and Heideggerian ontology.”

Naturally, “from this point on, French intellectuals stopped talking about ‘consciousness’ or ‘subject’ and started talking about ‘rules’ and ‘structure.’

The era of structuralism has truly begun.

He also realized that human nature lies in 'giving'.

Society needs to “continuously change” in order to continue to exist, and thus, “gift,” an act of “reciprocal consideration” that involves continuously giving and receiving something, is one of the important subjects of anthropology and a fundamental principle that supports human society.

Levi-Strauss reminded us of the important fact that “all social systems created by humans are so structured that they cannot remain in the same state,” and that “if we want something, we must first give it to others.”

We often believe that “human nature remains the same, and the most rational way to acquire something is to monopolize it and not give it to anyone else.”

But if you think about it carefully, human society has not allowed such a “static and selfish lifestyle.”

This human insight of Leviström is one of the most valuable insights we can gain from reading this book.

Lacan, in search of the value of communication

Finally, the last chapter of this book, "Chapter 6: Lacan and Analytical Dialogue," discusses Lacan, the last of the "Four Musketeers of Structuralism" and the most difficult of all.

Lacan's specialty was psychoanalysis, and he famously said, "Go back to Freud."

It could be said that “Lacan’s work literally delved deep into the path pioneered by Freud.”

According to Lacan, “humans become ‘normal adults’ after experiencing two major ‘fraudulent acts’ in their lives.

The first is to obtain the foundation of the ‘I’ by thinking of ‘what is not me’ as ‘I’ in the mirror stage, and the second is to explain one’s powerlessness and incompetence as a result of the threatening intervention of the ‘father’ through the Oedipus stage.”

Lacan's argument is interesting in that a 'normal adult' or 'human' is "one who has properly completed these two self-deceptions."

Lacan also emphasized that the purpose of psychoanalysis is not to uncover the 'cause' but to 'cure'.

'Treatment' at this time means bringing the analysand (patient) who has reached a standstill in communication, that is, in a dialogue with each other, back into the circuit of communication.

This is a meaningful act that brings the analysand into “a reciprocal cycle of giving and reciprocation, of exchanging words, sharing love, and sharing goods and services with others.”

As we read this book, we realize that “reactivating” “stagnant communication” through the sharing of stories is the most excellent way, not only for psychoanalysis but for all humans to “coexist” with others in a humane manner.

This book is significant in that it shows that Lacan's theory, notoriously difficult, was ultimately a process of exploring what we truly need for the healthy continuation of human relationships.

The era of structuralism is not over.

This book originated from the author's lecture notes for a structuralist civic course for the general public, and was published at the urging of a publisher who was disappointed that the author's famous lectures were limited to a single edition.

Since its publication in 2002, it has been recognized as one of the most outstanding introductory books on structuralism, and readers who have been curious about structuralism but have been burdened by the labyrinthine and complex theories will be delighted to find this book.

Professor Uchida, who has a remarkable talent for explaining difficult ideas and concepts in a unique way, makes it as easy and enjoyable as possible for people to approach structuralism through excellent analogies, meticulous explanations, and various quotations, rather than explaining complex and difficult theories about structuralism.

Tracing the entire history of structuralism through the great ideas and protagonists that heated up history makes readers feel more like they are listening to a wonderful lecture right before their eyes than reading a book.

Before reading this book, we can ask one question.

Is structuralism still relevant in this day and age? The answer this book presents is a resounding yes.

The voice of structuralism, which encourages us to shake off arrogance and prejudice and recognize ourselves within a diverse world, is what we need most in this age of rampant "absence of communication."

Structuralism awakens us to the value of true equality and teaches us how to communicate with the world, how to recognize ourselves, and how to redefine our relationships with others.

In that respect, there is no doubt that structuralism is an issue that must be continuously discussed now and in the future.

Knowing the nature of structuralism and understanding it closely will be the most important first step toward understanding my current life and building a better tomorrow and a more advanced society.

That is why this book is valuable to everyone as an essential 'university textbook'.

Recommendation

This book is a compilation of the vast achievements of Saussure, Levi-Strauss, Foucault, Roland Barthes, and Lacan, translated into colloquial sentences, and then summarized into lecture notes.

It's so easy to read, and I'm amazed at how such complex content is broken down into such fine pieces.

---From reader reviews

I've read several introductory books on structuralism, but none have been this easy to understand and fun.

I highly recommend you read it.

---From reader reviews

It has never fallen from its position as a bestseller.

The best introduction to structuralism!

『Easy Reading of Foucault, Barthes, Levi-Strauss, and Lacan - Structuralism Lectures for the Cultured』 is a book that provides an overview of structuralism as a whole, focusing on the so-called "Four Musketeers of Structuralism": Foucault, Barthes, Levi-Strauss, and Lacan.

Although there are already many works on structuralism, the appearance of this book is welcome, as it is difficult to find an easily readable one.

Professor Tatsuro Uchida, the author, demonstrates his forte in explaining difficult ideas and theories in an easy-to-understand way, neatly organizing the definition of structuralism, its origins and history, and its representative figures and ideas in a way that is easy to understand at a glance.

In short, this book is an excellent introduction to structuralism that will be useful to both those studying structuralism and general readers interested in structuralism.

Chapter 1, "Pre-structuralism History," examines the core ideas of Marx, Freud, and Nietzsche, who laid the foundation for structuralism before the full-fledged structuralist era began. Chapter 2, "The Emergence of Saussure, the Founder," examines Saussure's structuralist linguistics, which ushered in the era of structuralism.

In "Chapter 3: Foucault and Genealogical Thinking," we examine the social history work of Foucault, the first of the "Four Musketeers of Structuralism," and in "Chapter 4: Barthes and the Leadership of Writing," we examine the core ideas of Barthes, the second of the "Four Musketeers of Structuralism," who made a significant contribution to critical theory.

In "Chapter 5, Levi-Strauss and the Never-ending Gift," we will encounter the structuralist anthropology of Levi-Strauss, the third of the "Four Musketeers," the greatest cultural anthropologist of the 20th century. In the final chapter, "Chapter 6, Lacan and Analytical Dialogue," we will learn about the psychoanalysis of Lacan, the last of the "Four Musketeers."

As the translator says, “The reason we should be interested in structuralism is, as is the essence of all learning, to live better and be happier,” this book contains more than just “textbook” information, allowing us to look back on the current significance of structuralism through its human aspects that are not easily seen in other books.

Are humans 'autonomous subjects'?

What is structuralism? Professor Uchida defines it in one word in the introduction to this book: a way of thinking.

“We always belong to a certain era and a certain social group, and those conditions fundamentally determine our views, how we feel, and how we think.

So we are not living as freely or as autonomously as we think.

Rather, in most cases, we tend to selectively see, feel, or think only what is accepted by the social group to which we belong.

“What the group unconsciously excludes will never enter our sight, will never clash with our sensibilities, and will never become the subject of our reflections.” (p.

27)

The author's explanation is clear.

In short, we believe that we are “autonomous subjects” who make our own judgments and actions, but in fact, that freedom and autonomy are extremely limited.

This is the core of structuralism discussed throughout this book.

So where did this kind of thinking originate? To understand the origins of structuralism, the author first explores the question, "Is there truly such a thing as objectivity in our thinking and judgment?" By bringing together three controversial figures who have had a profound impact on later generations,

Just the names alone are impressive: Marx, Freud, and Nietzsche.

In Chapter 1, "Pre-structuralism History," we encounter these historical figures who laid the foundations of structuralism before the full-fledged structuralist era began.

Laying the groundwork for structuralism

Marx spent his entire life deeply delving into the question, "What special conditions are responsible for the formation of human thought and judgment?"

Accordingly, he focused on “class” as a factor that plays an important role in the historical change of social groups.

In other words, “the individuality of a human being is determined not by ‘who he is’ but by ‘what he does.’”

The fact that the origin of subjectivity lies not in the subject's 'existence' but in the subject's 'action' is the most fundamental concept of structuralism and an important idea shared by all structuralists.

For this reason, Marx is pointed out as the most decisive contributor who laid the foundation for the later era of structuralism.

Freud, on the other hand, focused on the innermost realm of human beings.

He believed that “human thoughts and actions are governed by mental activities that humans cannot directly perceive.”

Something that one may not be aware of, but nevertheless governs one's actions and judgments.

The 'unconscious' was born.

Among those who lived in the same era as these people, there was another person who argued that “human thought is not free,” and that person was Friedrich Nietzsche.

Nietzsche argued that “humans are, for the most part, nothing more than slaves to external norms,” and that “what we take for granted” are in fact “prejudices peculiar to a certain age or region.”

His statement that “we can never be ‘knowers’ of ourselves” is quite significant.

This book shows that their thoughts have a deep “common ground”: that “humans are not the protagonists of their own mental lives.”

“Marx saw that humans appear to think freely, but in reality they think in terms of classes,” “Freud saw that humans appear to think freely, but in reality they think without knowing ‘through what process’ they are thinking,” and Nietzsche saw that humans are beings who change according to their external environment.

Although it is difficult to see structuralism as directly expressed in their thoughts, it is clear that they played a key role in leveling the ground for structuralism.

Saussure ushered in the era of structuralism.

So who truly ushered in the era of structuralism? "Around the same time that Freud was lecturing on psychoanalysis in Vienna," at the University of Geneva in Switzerland, "a linguist was giving a 'lecture on general linguistics' to a small group of linguists and linguistics students."

Ferdinand de Saussure.

He is the person who is evaluated as having started structuralism in the history of thought.

In Chapter 2, "The Emergence of Saussure, the Founder," we observe the process of the prelude to the era of structuralism opening through the core content of Saussure's thought.

The author cites Saussure's linguistics as "the most important view that structuralism received": "Language is not 'the name of things.'"

Following the traditional view of language since Greece, language has been recognized as the name of things, but Saussure did not agree with that.

In his theory, he taught that “names of things are given arbitrarily by human beings” and that things and their names are not “connected by any special necessity.”

He also argued that “the nature, meaning, and function of something are later determined by what ‘position’ it occupies within the network or system that includes it.”

But at the same time, Saussure reminded us that “as long as we use language, we always endorse and reinforce the values of the linguistic community to which we belong.”

In other words, 'what is being said inside me when I speak' is mostly 'the words of others' who belong to the same community.

Therefore, the author argues that if “when I speak,’ the words are bound by the rules of the Korean language and consist of prescribed vocabulary,” then “most of what we ‘say’ is obtained from others, and then it would be shameful to say ‘I speak.’”

The obvious fact that the origins of what I say are actually mostly outside of me comes from Saussure.

This theory, “taught by a single linguist in a small classroom at the University of Geneva in the early 20th century,” has since developed into various schools and fields.

The prelude to structuralism began in such an exciting way.

Foucault, in search of the origin of the 'I'

This book classifies the post-war French generation, who were baptized in this new way of thinking, from Saussure through the Prague School, as the 'third generation' of structuralism, and its representative figures are Michel Foucault in the field of social history, Roland Barthes in semiotics, Lévi-Strauss in anthropology, and Lacan in psychoanalysis.

The author calls them the so-called 'Four Musketeers', the most important of structuralism, and devotes a significant portion of the book to explaining their ideas.

In Chapter 3 of this book, “Foucault and Genealogical Thinking,” we examine an outline of Foucault’s thought.

We often forget that “every civilization has its own birth date, and we can only know what it is by understanding the context of its own history leading to its birth.”

And there are countless cases where people arbitrarily think, “What I am seeing is something that has always existed, and the society I live in has always been like this.”

Foucault devoted himself steadfastly to his research with the goal of “destroying these foolish beliefs” of human beings.

In many of his representative works, such as 『Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison』, 『A History of Madness』, and 『The Archaeology of Knowledge』, he explores the true origins of things.

“Whether it be ‘prison,’ ‘madness,’ or ‘academics,’ we all mistakenly believe that it is fundamentally the same everywhere and at all times, regardless of era or region.”

“However, all social institutions existing in human society were born at some point in the past as a complex effect of several historical facts and did not exist before that time.”

“Foucault’s ‘social history’ work is to point out this extremely obvious (but easily forgotten) fact and to go back to the site where the system or meaning was created.”

“What kind of history did this ‘I’ here go through to form?” This book shows that asking this question is the core of the ‘critical structure’ that Foucault advocated.

However, the author confesses that this is actually a limited hope, like “wanting to see the back of one’s own head with one’s own eyes.”

Perhaps it is because Foucault gave his all to that impossible task that his life and thoughts are all the more moving to us.

Barthes, 'The author is dead.'

Barth's views are very diverse, and in Chapter 4, Barth and the Leadership of Writing, this book examines the core of Barth's thought, particularly the concept of 'écriture' and the 'death of the author.'

As Saussure pointed out, “our modes of thought and experience depend so much on the language we use that when the language we use changes, our modes of thought and experience also change.”

That is, even when we believe we are using our native language freely, “language operates according to some invisible rules that we are not aware of.”

These rules are 'language' and 'still'.

Langue is a “regulation from the outside,” that is, “a set of rules and habits shared by all writers of a given era,” while still is our personal sense of language that “regulates our language use ‘from the inside’” when we speak.

And in addition to these, there is a third element that regulates our use of language: 'écriture'.

According to Barthes, écriture is a “‘preference’ that is collectively chosen and practiced,” which signifies the choice of “the social field that the writer must assign to his ‘natural’ language.”

This concept has influenced the recognition of the existence of a “‘intertwined’ structure” between grammar and human society, or between text and reader, and has presented this as a “basic principle of criticism.”

Barth also denied the principle of modern criticism that views the author as someone who creates from nothing.

A ‘text’ is a kind of ‘fabric’, and ‘many things are needed’ to create a single piece of text, and this ‘fabric’, which is filled with various elements from various places through various processes, cannot be said to have been completed by a single person.

This is the 'death of the author'.

His new concept signaled that the era in which the modern concept of 'author' was in common use had already passed, and that the birth of the reader required the "death of the author."

Barthes's attitude of finding "joy" in the "movement of text creation" itself, regardless of the "fame, profit, or power" that "copyright" brings, leaves much food for thought, especially for modern people living in the Internet age.

Levi-Strauss, breaking down the boundaries between 'barbarism' and 'civilization'

Following Foucault and Barthes, Chapter 5 of this book, “Levi-Strauss and the Never-ending Gift,” introduces the ideas of Lévi-Strauss, the greatest cultural anthropologist of the 20th century.

Levi-Strauss is a pioneer of structuralist anthropology who surprised the world with his bold approach of “interpreting kinship structure as a theoretical model of phonology.”

Influenced by Roman Jakobson of the Prague School, a direct descendant of Saussure, he combined linguistics with the analytical methods of anthropology to reconstruct 'uncivilized society' into 'another civilized society.'

In short, 'civilized people' and 'savages' only have different ways of taking interest in things, but the fact that 'savages' do not see the world like 'civilized people' does not mean that they are intellectually inferior.

His contemporaries were astonished to see his theory, based on extensive fieldwork, “crushing Sartre’s existentialism, ‘fully armed’ with Marxism and Heideggerian ontology.”

Naturally, “from this point on, French intellectuals stopped talking about ‘consciousness’ or ‘subject’ and started talking about ‘rules’ and ‘structure.’

The era of structuralism has truly begun.

He also realized that human nature lies in 'giving'.

Society needs to “continuously change” in order to continue to exist, and thus, “gift,” an act of “reciprocal consideration” that involves continuously giving and receiving something, is one of the important subjects of anthropology and a fundamental principle that supports human society.

Levi-Strauss reminded us of the important fact that “all social systems created by humans are so structured that they cannot remain in the same state,” and that “if we want something, we must first give it to others.”

We often believe that “human nature remains the same, and the most rational way to acquire something is to monopolize it and not give it to anyone else.”

But if you think about it carefully, human society has not allowed such a “static and selfish lifestyle.”

This human insight of Leviström is one of the most valuable insights we can gain from reading this book.

Lacan, in search of the value of communication

Finally, the last chapter of this book, "Chapter 6: Lacan and Analytical Dialogue," discusses Lacan, the last of the "Four Musketeers of Structuralism" and the most difficult of all.

Lacan's specialty was psychoanalysis, and he famously said, "Go back to Freud."

It could be said that “Lacan’s work literally delved deep into the path pioneered by Freud.”

According to Lacan, “humans become ‘normal adults’ after experiencing two major ‘fraudulent acts’ in their lives.

The first is to obtain the foundation of the ‘I’ by thinking of ‘what is not me’ as ‘I’ in the mirror stage, and the second is to explain one’s powerlessness and incompetence as a result of the threatening intervention of the ‘father’ through the Oedipus stage.”

Lacan's argument is interesting in that a 'normal adult' or 'human' is "one who has properly completed these two self-deceptions."

Lacan also emphasized that the purpose of psychoanalysis is not to uncover the 'cause' but to 'cure'.

'Treatment' at this time means bringing the analysand (patient) who has reached a standstill in communication, that is, in a dialogue with each other, back into the circuit of communication.

This is a meaningful act that brings the analysand into “a reciprocal cycle of giving and reciprocation, of exchanging words, sharing love, and sharing goods and services with others.”

As we read this book, we realize that “reactivating” “stagnant communication” through the sharing of stories is the most excellent way, not only for psychoanalysis but for all humans to “coexist” with others in a humane manner.

This book is significant in that it shows that Lacan's theory, notoriously difficult, was ultimately a process of exploring what we truly need for the healthy continuation of human relationships.

The era of structuralism is not over.

This book originated from the author's lecture notes for a structuralist civic course for the general public, and was published at the urging of a publisher who was disappointed that the author's famous lectures were limited to a single edition.

Since its publication in 2002, it has been recognized as one of the most outstanding introductory books on structuralism, and readers who have been curious about structuralism but have been burdened by the labyrinthine and complex theories will be delighted to find this book.

Professor Uchida, who has a remarkable talent for explaining difficult ideas and concepts in a unique way, makes it as easy and enjoyable as possible for people to approach structuralism through excellent analogies, meticulous explanations, and various quotations, rather than explaining complex and difficult theories about structuralism.

Tracing the entire history of structuralism through the great ideas and protagonists that heated up history makes readers feel more like they are listening to a wonderful lecture right before their eyes than reading a book.

Before reading this book, we can ask one question.

Is structuralism still relevant in this day and age? The answer this book presents is a resounding yes.

The voice of structuralism, which encourages us to shake off arrogance and prejudice and recognize ourselves within a diverse world, is what we need most in this age of rampant "absence of communication."

Structuralism awakens us to the value of true equality and teaches us how to communicate with the world, how to recognize ourselves, and how to redefine our relationships with others.

In that respect, there is no doubt that structuralism is an issue that must be continuously discussed now and in the future.

Knowing the nature of structuralism and understanding it closely will be the most important first step toward understanding my current life and building a better tomorrow and a more advanced society.

That is why this book is valuable to everyone as an essential 'university textbook'.

Recommendation

This book is a compilation of the vast achievements of Saussure, Levi-Strauss, Foucault, Roland Barthes, and Lacan, translated into colloquial sentences, and then summarized into lecture notes.

It's so easy to read, and I'm amazed at how such complex content is broken down into such fine pieces.

---From reader reviews

I've read several introductory books on structuralism, but none have been this easy to understand and fun.

I highly recommend you read it.

---From reader reviews

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: October 5, 2010

- Page count, weight, size: 224 pages | 297g | 142*200*20mm

- ISBN13: 9788990809339

- ISBN10: 8990809339

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)