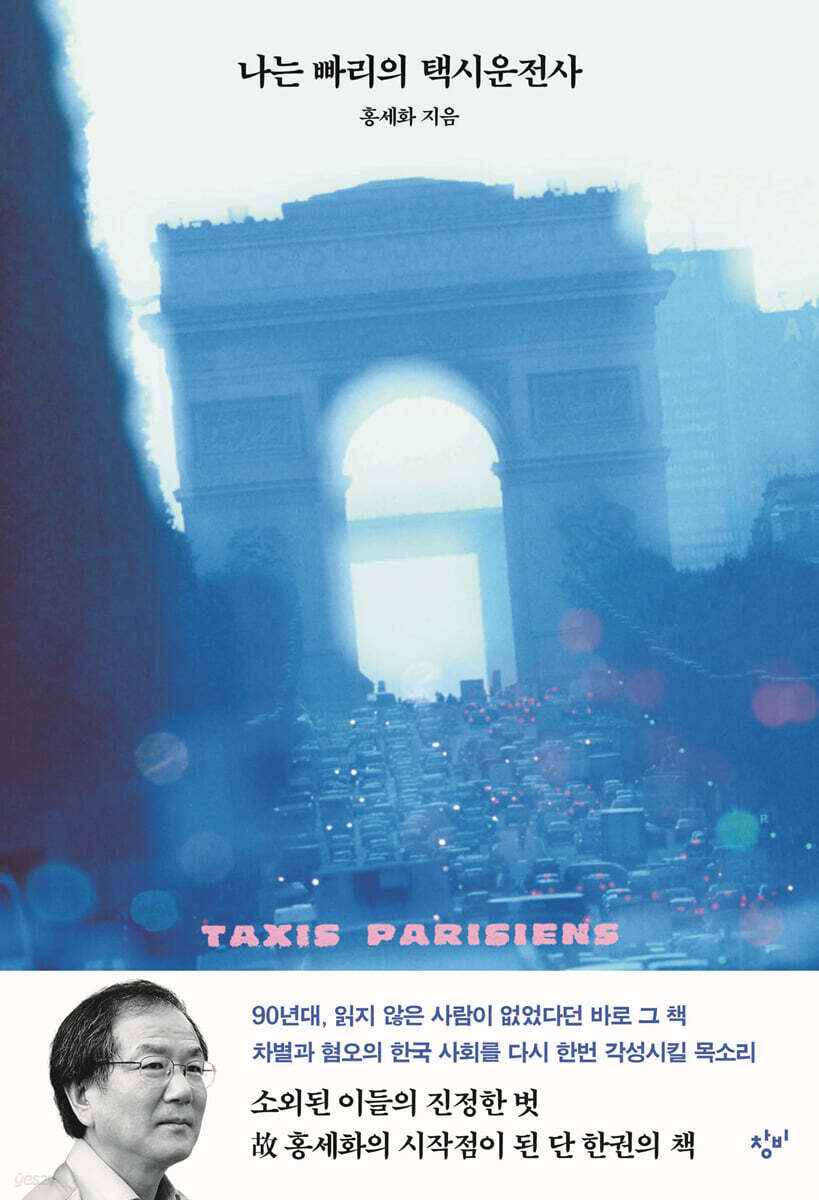

I am a taxi driver in Paris

|

Description

Book Introduction

The book that everyone in the 90s read

A voice that will once again awaken Korean society, fraught with division and hatred.

The book that first made the name 'Hong Se-hwa' known in Korean society, 'I am a Taxi Driver in Paris', has returned in a revised and expanded edition.

When this book was first published in 1995, 30 years ago, it became an instant bestseller, introducing the concept of "tolerance," which means common-sense respect and tolerance for others, to a Korean society that was still rigid due to the aftermath of military dictatorship.

In Korean society, where hatred and rejection of others due to differences in ideology and beliefs were taken for granted, the arrival of tolerance was truly shocking and sparked an explosive response.

After that, 『I am a Taxi Driver in Paris』 became known as 'a book you would be ashamed not to read' and was at the center of enthusiasm for a long time.

This book arrived 30 years ago, as if bringing an end to a dark era, and was a hit with the youth of the 1990s who yearned for change, but we still live in a society in desperate need of 'tolerance.'

In a society where differences are intolerance, differences are used as grounds for discrimination and oppression, and division is more readily chosen over coexistence, dialogue, compromise, respect, and recognition are increasingly being pushed to the margins.

As a result of tolerating a social atmosphere fueled by hatred toward others and attempting to suppress opposing opinions, citizens have become extremely conflicted even in the plazas of the impeachment crisis, where we should all be moving together toward a better democracy, and reconciliation remains the most urgent task before us.

Therefore, as the author of this book, Hong Se-hwa, said in the preface to the 2006 revised edition, 'Tolerance is still valid because the world has changed and yet nothing has changed.

It will remain valid for a very long time to come.' (Page 6) Now, as we must overcome the crisis and rewrite the narrative of democracy, it is undoubtedly the right time to revisit and digest Hong Se-hwa's tolerance.

This revised and expanded edition, which commemorates the 30th anniversary of the publication and the first anniversary of Hong Se-hwa's passing, is even more meaningful with the addition of a eulogy from Hong Se-hwa's longtime friend, former Cultural Heritage Administration Commissioner Yoo Hong-joon, and the author's last column contributed to the Hankyoreh in 2023.

A voice that will once again awaken Korean society, fraught with division and hatred.

The book that first made the name 'Hong Se-hwa' known in Korean society, 'I am a Taxi Driver in Paris', has returned in a revised and expanded edition.

When this book was first published in 1995, 30 years ago, it became an instant bestseller, introducing the concept of "tolerance," which means common-sense respect and tolerance for others, to a Korean society that was still rigid due to the aftermath of military dictatorship.

In Korean society, where hatred and rejection of others due to differences in ideology and beliefs were taken for granted, the arrival of tolerance was truly shocking and sparked an explosive response.

After that, 『I am a Taxi Driver in Paris』 became known as 'a book you would be ashamed not to read' and was at the center of enthusiasm for a long time.

This book arrived 30 years ago, as if bringing an end to a dark era, and was a hit with the youth of the 1990s who yearned for change, but we still live in a society in desperate need of 'tolerance.'

In a society where differences are intolerance, differences are used as grounds for discrimination and oppression, and division is more readily chosen over coexistence, dialogue, compromise, respect, and recognition are increasingly being pushed to the margins.

As a result of tolerating a social atmosphere fueled by hatred toward others and attempting to suppress opposing opinions, citizens have become extremely conflicted even in the plazas of the impeachment crisis, where we should all be moving together toward a better democracy, and reconciliation remains the most urgent task before us.

Therefore, as the author of this book, Hong Se-hwa, said in the preface to the 2006 revised edition, 'Tolerance is still valid because the world has changed and yet nothing has changed.

It will remain valid for a very long time to come.' (Page 6) Now, as we must overcome the crisis and rewrite the narrative of democracy, it is undoubtedly the right time to revisit and digest Hong Se-hwa's tolerance.

This revised and expanded edition, which commemorates the 30th anniversary of the publication and the first anniversary of Hong Se-hwa's passing, is even more meaningful with the addition of a eulogy from Hong Se-hwa's longtime friend, former Cultural Heritage Administration Commissioner Yoo Hong-joon, and the author's last column contributed to the Hankyoreh in 2023.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Preface to the Revised Edition (2006)

Preface to the First Edition (1995)

Chief: "Come to Paris."

Part 1: A Stranger in Paris

What country are you from?

The meeting of one society and another

gentile

The land I left behind

Asking for directions

Farewell! Junk Taxi

I also refused to ride

Sylvie and Sylvie

Apply for asylum, countries you cannot go to

Part 2: Korea, a country you can't go to

Flashback 1: The Cruel Land

Koreans I met as taxi passengers

Wandering around Paris

a single red rose

To Soo-hyeon and Yong-bin

Flashback 2: The Season of Wandering

Flashback 3 Call of the Heart

Nguyen and I

Last tears

Tolerance in French society

The final request: From ownership to relationships, from growth to maturity

Eulogy: Upright Intellect, or Simple Freedom | Yoo Hong-jun

Preface to the First Edition (1995)

Chief: "Come to Paris."

Part 1: A Stranger in Paris

What country are you from?

The meeting of one society and another

gentile

The land I left behind

Asking for directions

Farewell! Junk Taxi

I also refused to ride

Sylvie and Sylvie

Apply for asylum, countries you cannot go to

Part 2: Korea, a country you can't go to

Flashback 1: The Cruel Land

Koreans I met as taxi passengers

Wandering around Paris

a single red rose

To Soo-hyeon and Yong-bin

Flashback 2: The Season of Wandering

Flashback 3 Call of the Heart

Nguyen and I

Last tears

Tolerance in French society

The final request: From ownership to relationships, from growth to maturity

Eulogy: Upright Intellect, or Simple Freedom | Yoo Hong-jun

Detailed image

Into the book

They say the world has changed.

It's true.

It was thanks to the world changing that I was able to come back.

But isn't that change merely a shift in the patterns of inequality, oppression, and exclusion—in other words, a shift from overt to covert, yet structural? (...) In this world, where "things have changed yet remain the same," the message of this book—"tolerance," which urges us not to use differences as a basis for discrimination, oppression, and exclusion—remains valid.

It will remain in effect for a very long time to come.

--- From the "Preface to the Revised Edition"

‘The meeting of one society and another’, the first thing it brought to me was tears.

(…) However, the ‘meeting of one society with another’ was something that should not end with that meeting or tears.

Meetings and tears both come from love and demand love.

Moreover, that love necessarily requires engagement within society.

But to me, it just appeared as 'an endless battle with myself.'

--- From "The Encounter of One Society and Another"

I was confirming for myself that 'when circumstances change, consciousness also changes accordingly.'

In the past, when I read a literary work or watched a movie, my consciousness would naturally identify myself only with the main character, but now my consciousness is aligning itself with the 'extra' rather than the 'main character'.

(…) I was a stranger, an extra stranger, and a triple stranger.

--- From "The Stranger"

In a society with tolerance, that is, a society that persuades, people do not hate, expel, or look down on others.

Instead of fighting each other, they chatted loudly in the cafe.

He was talkative and placed great importance on rhetoric.

And since coercion didn't work, there was no room for prejudice.

The taxi driver was recognized as a taxi driver, that is, as he was.

This means that when I, a taxi driver, make a mistake while driving the taxi, I can be criticized by the customer, but I will not be treated with contempt because I am a taxi driver.

--- From "Adieu! Junk Taxi"

I had to explain that Korea was a country I could not return to.

I had to say that things that could only happen in Haiti, the country of Tonton Macoute, or in some other African country, were and are being committed under the Park Chung-hee and Chun Doo-hwan regimes in Korea.

Even though it was true, I hated myself for saying it.

I was floundering.

Finally, I struggled with the urge to cry.

It was because I looked so pathetic, stammering in my broken English to get my asylum application accepted.

--- From "Application for Asylum, Countries You Cannot Go To"

“In Korea, communists are called communists.

Communists are red, socialists are red, progressives are red, and those who are critical of America are also red.

And Korea is a place where both idealists and humanists can become communists.

(…) Are you a socialist? A leftist? The terms left and right are relative.

To the far right, everyone who is not far right is left.

In Korea, all these leftists can be communists.

When you don't keep silent.

Therefore, Korea is the place where all existentialists who are not far-right must become communists.”

--- From "Application for Asylum, Countries You Cannot Go To"

I learned to hate before I learned to love.

I was taught and firmly believed that the other side of the river was nothing but an object of hatred, and yet I was right there.

I am divided.

I couldn't love my newfound self.

I was a person who 'couldn't love myself'.

So I was dismantled.

Before I left there and even arrived in Seoul, I was already an empty shell.

All the dreams, values, and even the 'KS mark' that I had held onto until then were all shattered.

Pride and the so-called elite consciousness disappeared along with everything else.

A person who cannot love himself has difficulty having self-respect, let alone self-respect.

And so my wanderings began.

--- From "Memories 1, The Cruel Land"

My wanderings demanded existence.

It was a natural conclusion.

I read Sartre and Camus.

(…) I learned that you can fool everyone else, but you can’t fool yourself.

It became the principle of my life.

The rock of Sisyphus that Camus spoke of brought up a special image for me.

The tragedy of Sisyphus, who pushed the rock to the top knowing that it would roll back down, was a desperate one, but it was resistance and a thorough life.

I too became Sisyphus.

Filling the river with rocks.

Even if it flows down and sinks again, it fills up again and again.

It's constantly, constantly filling up that river.

To Sisyphus' rock, to my rock.

--- From "Reminiscence 2, Season of Wandering"

I wasn't a thorough revolutionary.

He wasn't even a theorist.

And any political desires were far from me.

I reflected on the meaning of my life and tried to be true to it.

I wanted to love myself and love everyone who wasn't me.

So, I wanted to resist division and live as one.

That was exactly what my heart was asking for.

That was it.

--- From "Reminiscence 3, Call of the Heart"

Political ideologies and religious beliefs cannot be changed by force, although they can be changed by persuasion.

If they were ideologies or beliefs that could be abandoned overnight by force, they would no longer be ideologies or beliefs, but merely falsehoods.

Therefore, if you believe that you can force someone to change their political ideology or religious beliefs just because they are different from you, that is simply a lack of understanding of humanity and an insult to the ideologies and beliefs that only humans can possess.

It's true.

It was thanks to the world changing that I was able to come back.

But isn't that change merely a shift in the patterns of inequality, oppression, and exclusion—in other words, a shift from overt to covert, yet structural? (...) In this world, where "things have changed yet remain the same," the message of this book—"tolerance," which urges us not to use differences as a basis for discrimination, oppression, and exclusion—remains valid.

It will remain in effect for a very long time to come.

--- From the "Preface to the Revised Edition"

‘The meeting of one society and another’, the first thing it brought to me was tears.

(…) However, the ‘meeting of one society with another’ was something that should not end with that meeting or tears.

Meetings and tears both come from love and demand love.

Moreover, that love necessarily requires engagement within society.

But to me, it just appeared as 'an endless battle with myself.'

--- From "The Encounter of One Society and Another"

I was confirming for myself that 'when circumstances change, consciousness also changes accordingly.'

In the past, when I read a literary work or watched a movie, my consciousness would naturally identify myself only with the main character, but now my consciousness is aligning itself with the 'extra' rather than the 'main character'.

(…) I was a stranger, an extra stranger, and a triple stranger.

--- From "The Stranger"

In a society with tolerance, that is, a society that persuades, people do not hate, expel, or look down on others.

Instead of fighting each other, they chatted loudly in the cafe.

He was talkative and placed great importance on rhetoric.

And since coercion didn't work, there was no room for prejudice.

The taxi driver was recognized as a taxi driver, that is, as he was.

This means that when I, a taxi driver, make a mistake while driving the taxi, I can be criticized by the customer, but I will not be treated with contempt because I am a taxi driver.

--- From "Adieu! Junk Taxi"

I had to explain that Korea was a country I could not return to.

I had to say that things that could only happen in Haiti, the country of Tonton Macoute, or in some other African country, were and are being committed under the Park Chung-hee and Chun Doo-hwan regimes in Korea.

Even though it was true, I hated myself for saying it.

I was floundering.

Finally, I struggled with the urge to cry.

It was because I looked so pathetic, stammering in my broken English to get my asylum application accepted.

--- From "Application for Asylum, Countries You Cannot Go To"

“In Korea, communists are called communists.

Communists are red, socialists are red, progressives are red, and those who are critical of America are also red.

And Korea is a place where both idealists and humanists can become communists.

(…) Are you a socialist? A leftist? The terms left and right are relative.

To the far right, everyone who is not far right is left.

In Korea, all these leftists can be communists.

When you don't keep silent.

Therefore, Korea is the place where all existentialists who are not far-right must become communists.”

--- From "Application for Asylum, Countries You Cannot Go To"

I learned to hate before I learned to love.

I was taught and firmly believed that the other side of the river was nothing but an object of hatred, and yet I was right there.

I am divided.

I couldn't love my newfound self.

I was a person who 'couldn't love myself'.

So I was dismantled.

Before I left there and even arrived in Seoul, I was already an empty shell.

All the dreams, values, and even the 'KS mark' that I had held onto until then were all shattered.

Pride and the so-called elite consciousness disappeared along with everything else.

A person who cannot love himself has difficulty having self-respect, let alone self-respect.

And so my wanderings began.

--- From "Memories 1, The Cruel Land"

My wanderings demanded existence.

It was a natural conclusion.

I read Sartre and Camus.

(…) I learned that you can fool everyone else, but you can’t fool yourself.

It became the principle of my life.

The rock of Sisyphus that Camus spoke of brought up a special image for me.

The tragedy of Sisyphus, who pushed the rock to the top knowing that it would roll back down, was a desperate one, but it was resistance and a thorough life.

I too became Sisyphus.

Filling the river with rocks.

Even if it flows down and sinks again, it fills up again and again.

It's constantly, constantly filling up that river.

To Sisyphus' rock, to my rock.

--- From "Reminiscence 2, Season of Wandering"

I wasn't a thorough revolutionary.

He wasn't even a theorist.

And any political desires were far from me.

I reflected on the meaning of my life and tried to be true to it.

I wanted to love myself and love everyone who wasn't me.

So, I wanted to resist division and live as one.

That was exactly what my heart was asking for.

That was it.

--- From "Reminiscence 3, Call of the Heart"

Political ideologies and religious beliefs cannot be changed by force, although they can be changed by persuasion.

If they were ideologies or beliefs that could be abandoned overnight by force, they would no longer be ideologies or beliefs, but merely falsehoods.

Therefore, if you believe that you can force someone to change their political ideology or religious beliefs just because they are different from you, that is simply a lack of understanding of humanity and an insult to the ideologies and beliefs that only humans can possess.

--- From "Boron, Tolerance in French Society"

Publisher's Review

The only Korean taxi driver in Paris

Looking at Two Societies Through the Eyes of an Exile and a Foreigner

In 1979, at the end of the Yushin era, many members of the Namminjeon (Preparatory Committee for the South Korean National Liberation Front), which had been secretly fighting against the dictatorship, were arrested.

The Namminjeon was disbanded under false pretenses of being a spy organization that violated the National Security Act, and its "fighters" were sentenced to death or life imprisonment one after another.

At this time, there was someone who had to watch from a faraway country the insults and violence inflicted on his colleagues. That person was Hong Se-hwa.

He was also a member of the Namminjeon, but at the time, he happened to be living in Paris.

In a time when anyone associated with the Namminjeon was branded a “communist” or a “spy” and thrown in prison, he was unable to return to his home country and was suddenly forced into exile, having to worry about his immediate livelihood.

Eventually, he chose to work as a taxi driver to survive.

After 20 years, he worked as the only Korean taxi driver in Paris and wrote an autobiographical essay titled “I am a Taxi Driver in Paris” about his experiences and struggles as an outsider who could not fully belong to either Korean or French society.

“I was a triple stranger,” says Hong Se-hwa (page 81).

He was unable to set foot on his homeland simply because he had rebelled against the system, and in Paris he was constantly asked, “Where are you from?” (p. 44), and even the Korean community in Paris branded him as a dangerous person and ostracized him.

He couldn't fit in anywhere and was not welcomed by anyone, but ironically, there was a truth that could only be seen in such places, which is why his voice in this book resonates even more deeply.

Hong Se-hwa was a vivid witness to the shock caused by “the meeting of one society with another” (p. 64).

For him, who had fled Korea in the 1970s to escape torture and imprisonment, everything the French enjoyed and practiced in their daily lives, especially their individuality, freedom of expression, and respect for the thoughts and circumstances of others, was painfully unfamiliar and enviable.

The French common sense he experienced while driving around Paris was surprisingly different from the common sense in Korea.

He observes French society, which prioritizes human dignity and equality above all else and thus guarantees that everyone can boldly assert their rights and opinions against vested interests, and he says, “It was a society I had never known before, and it was a squirm” (p. 69).

The gap between himself and French society, which he felt was “a land without gravity” (p. 404), is starkly revealed at the French Embassy where he goes to apply for asylum.

He had to explain to the secretariat officials why he could not return to Korea, but he could not properly convey the reality of the 'Yushin regime' and the 'emergency measures' with just a few words of English.

In particular, when the office manager asked him, “So what specifically did you do in that organization?” (page 187), in response to his statement that he was a member of the Namminjeon, he was left speechless.

It was nearly impossible to make the French understand the “absurd but undisputed fact” (p. 187) that “under Korea’s Yushin regime, one would be tortured in an interrogation room and face at least several years in prison” simply by “distributing leaflets calling for the overthrow of the Park Chung-hee military dictatorship on several occasions.” It was nearly impossible to make the French understand the reality of the division that made this possible.

In the end, unable to overcome his despair and anger, he shouts, “Korea is a place where both idealists and humanists can become communists” (page 193). This makes us look back on our dark past when we did not tolerate “different thoughts,” and at the same time, it bitterly reminds us of the ideological stigma that continues to this day.

“Our flint must be struck to shine.”

In a Korean society of division and hatred,

Why You Should Reread Hong Se-hwa

A society that must conform to the national ideology and a society that respects individual beliefs.

The question of what made the two societies so different inevitably deepened.

Hong Se-hwa diagnoses that the difference between the two societies stems from the presence or absence of 'tolerance.'

According to him, tolerance means, in a word, “respect for the freedom of others to think and act and for the freedom of others’ political and religious opinions” (p. 374).

If you want your ideas and beliefs to be respected, respect the ideas and beliefs of others.

This, he says, is “a demand of tolerance and a natural assertion of human reason” (p. 375).

So, in a society with tolerance, people do not blindly criticize or forcefully change the thoughts and positions of others.

The differences between our positions can only be narrowed through constant and intense dialogue.

The spirit of tolerance, which requires accepting others as they are, is not limited to the realms of politics or ideology.

It goes so far as to tolerate people of different nationalities, races, cultures, lifestyles, and identities.

In other words, tolerance is a kind of attitude toward life and the minimum consideration that is absolutely required in human society.

But what was the state of Korean society like?

Hong Se-hwa says that while tolerance supported France, what dominated the Korean Peninsula was “the ideology of hatred” (p. 71).

The history of division, in which the North and the South sought internal unity through mutual hatred and rejection, led to differences being viewed as threats and others as enemies.

A society that “hates communists thoroughly without even knowing what communism is” and “learns hatred before learning to love humanity” (p. 71) has undermined trust, solidarity, and mutual responsibility among people, and has torn the community apart.

Critical perspectives and opinions, as Voltaire said, “Our flints shine only when struck together” (p. 399), were often shattered by the logic of hatred and self-righteousness rather than being energized by clashing.

In this book, Hong Se-hwa reveals that she was a survivor of the civilian massacre that occurred during the Korean War, and also testifies to how cruel and irreparable the scars this ideology of hate can leave on a person's life.

Today's Korean society is also not free from these shadows.

The political reality that encourages division, the ideological conflict that is expressed violently in everyday life, and the hatred and discrimination against minorities and the weak show that the traces of hatred are still deeply engraved in our society.

In this reality, for the sustainability of democracy, tolerance must become a daily guideline and community ethics.

It is time to re-evaluate and practice the value of tolerance.

That is why Hong Se-hwa devotes a significant portion of this book to explaining tolerance under the title “Boron,” and why we need to reread this book now.

A true friend of the marginalized and an eternal outsider

The one book that became Hong Se-hwa's starting point

Hong Se-hwa returned to Korea permanently after publishing “I am a Taxi Driver in Paris” about 10 years ago.

The joy of returning to his homeland was short-lived, as he refused to adapt to the Korean society he was re-introduced to.

As an awakened critic, he practiced the spirit of tolerance he preached throughout his life.

As a journalist, politician, and social activist, he has boldly criticized the hypocrisy and self-righteousness of vested interests regardless of whether they are conservative or progressive.

Even if it was an opinion that was not welcomed by the majority, I did not bend if it contributed to creating a more equal and inclusive society.

It was a life that inevitably led him to become an 'outsider', but he kept heading towards lower and more remote places.

We stood together as friends of those who were pushed out there, refugees, sexual minorities, women, the disabled, irregular workers, and the poor.

He was a thinker and practitioner who diligently worked toward the ideals of true freedom, equality, and solidarity.

He was an adult of the time who silently showed us at the forefront what kind of world we should open.

Considering that before he went into exile, he was a member of the elite and a member of the establishment, aka the 'KS' mark, having graduated from Gyeonggi High School and Seoul National University in Korea, this is a truly surprising move.

It would not be an exaggeration to say that it was thanks to his 20 years in Paris that he, with such a background, was able to live as an 'evangelist of tolerance', an 'outsider', and a 'simple free man' without taking advantage of those in power.

It was probably possible because I never forgot the days when I had to endure the “bitterness of ‘survival’” (p. 114) while unexpectedly working as a taxi driver, when all my previous backgrounds became meaningless and I had to confront a different society with my bare body.

The customers who treated foreign taxi drivers who struggled with French as equals, the fellow taxi drivers who taught them the meaning of everyday solidarity, the free-spirited Parisians on the streets who laughed, chatted, put their arms around each other, and protested… This book contains the people, scenes, and anecdotes that completely changed his life, leaving him with unforgettable surprises, emotions, and bitterness.

Let's follow the story of Hong Se-hwa, who opens the book "I am a Taxi Driver in Paris", the one that became his starting point, and starts his journey by saying, "Come to Paris" (page 13).

Tolerance will become a living reality, not just a slogan, and will serve as a milestone for us as we navigate an era of division and disconnection.

* A memorial service and memorial cultural festival to commemorate the first anniversary of the passing of the late Hong Se-hwa and to remember his spirit together will be held on April 18, 2025 (Inquiries: Hong Se-hwa 1st Anniversary Memorial Committee 02-6004-2000).

Looking at Two Societies Through the Eyes of an Exile and a Foreigner

In 1979, at the end of the Yushin era, many members of the Namminjeon (Preparatory Committee for the South Korean National Liberation Front), which had been secretly fighting against the dictatorship, were arrested.

The Namminjeon was disbanded under false pretenses of being a spy organization that violated the National Security Act, and its "fighters" were sentenced to death or life imprisonment one after another.

At this time, there was someone who had to watch from a faraway country the insults and violence inflicted on his colleagues. That person was Hong Se-hwa.

He was also a member of the Namminjeon, but at the time, he happened to be living in Paris.

In a time when anyone associated with the Namminjeon was branded a “communist” or a “spy” and thrown in prison, he was unable to return to his home country and was suddenly forced into exile, having to worry about his immediate livelihood.

Eventually, he chose to work as a taxi driver to survive.

After 20 years, he worked as the only Korean taxi driver in Paris and wrote an autobiographical essay titled “I am a Taxi Driver in Paris” about his experiences and struggles as an outsider who could not fully belong to either Korean or French society.

“I was a triple stranger,” says Hong Se-hwa (page 81).

He was unable to set foot on his homeland simply because he had rebelled against the system, and in Paris he was constantly asked, “Where are you from?” (p. 44), and even the Korean community in Paris branded him as a dangerous person and ostracized him.

He couldn't fit in anywhere and was not welcomed by anyone, but ironically, there was a truth that could only be seen in such places, which is why his voice in this book resonates even more deeply.

Hong Se-hwa was a vivid witness to the shock caused by “the meeting of one society with another” (p. 64).

For him, who had fled Korea in the 1970s to escape torture and imprisonment, everything the French enjoyed and practiced in their daily lives, especially their individuality, freedom of expression, and respect for the thoughts and circumstances of others, was painfully unfamiliar and enviable.

The French common sense he experienced while driving around Paris was surprisingly different from the common sense in Korea.

He observes French society, which prioritizes human dignity and equality above all else and thus guarantees that everyone can boldly assert their rights and opinions against vested interests, and he says, “It was a society I had never known before, and it was a squirm” (p. 69).

The gap between himself and French society, which he felt was “a land without gravity” (p. 404), is starkly revealed at the French Embassy where he goes to apply for asylum.

He had to explain to the secretariat officials why he could not return to Korea, but he could not properly convey the reality of the 'Yushin regime' and the 'emergency measures' with just a few words of English.

In particular, when the office manager asked him, “So what specifically did you do in that organization?” (page 187), in response to his statement that he was a member of the Namminjeon, he was left speechless.

It was nearly impossible to make the French understand the “absurd but undisputed fact” (p. 187) that “under Korea’s Yushin regime, one would be tortured in an interrogation room and face at least several years in prison” simply by “distributing leaflets calling for the overthrow of the Park Chung-hee military dictatorship on several occasions.” It was nearly impossible to make the French understand the reality of the division that made this possible.

In the end, unable to overcome his despair and anger, he shouts, “Korea is a place where both idealists and humanists can become communists” (page 193). This makes us look back on our dark past when we did not tolerate “different thoughts,” and at the same time, it bitterly reminds us of the ideological stigma that continues to this day.

“Our flint must be struck to shine.”

In a Korean society of division and hatred,

Why You Should Reread Hong Se-hwa

A society that must conform to the national ideology and a society that respects individual beliefs.

The question of what made the two societies so different inevitably deepened.

Hong Se-hwa diagnoses that the difference between the two societies stems from the presence or absence of 'tolerance.'

According to him, tolerance means, in a word, “respect for the freedom of others to think and act and for the freedom of others’ political and religious opinions” (p. 374).

If you want your ideas and beliefs to be respected, respect the ideas and beliefs of others.

This, he says, is “a demand of tolerance and a natural assertion of human reason” (p. 375).

So, in a society with tolerance, people do not blindly criticize or forcefully change the thoughts and positions of others.

The differences between our positions can only be narrowed through constant and intense dialogue.

The spirit of tolerance, which requires accepting others as they are, is not limited to the realms of politics or ideology.

It goes so far as to tolerate people of different nationalities, races, cultures, lifestyles, and identities.

In other words, tolerance is a kind of attitude toward life and the minimum consideration that is absolutely required in human society.

But what was the state of Korean society like?

Hong Se-hwa says that while tolerance supported France, what dominated the Korean Peninsula was “the ideology of hatred” (p. 71).

The history of division, in which the North and the South sought internal unity through mutual hatred and rejection, led to differences being viewed as threats and others as enemies.

A society that “hates communists thoroughly without even knowing what communism is” and “learns hatred before learning to love humanity” (p. 71) has undermined trust, solidarity, and mutual responsibility among people, and has torn the community apart.

Critical perspectives and opinions, as Voltaire said, “Our flints shine only when struck together” (p. 399), were often shattered by the logic of hatred and self-righteousness rather than being energized by clashing.

In this book, Hong Se-hwa reveals that she was a survivor of the civilian massacre that occurred during the Korean War, and also testifies to how cruel and irreparable the scars this ideology of hate can leave on a person's life.

Today's Korean society is also not free from these shadows.

The political reality that encourages division, the ideological conflict that is expressed violently in everyday life, and the hatred and discrimination against minorities and the weak show that the traces of hatred are still deeply engraved in our society.

In this reality, for the sustainability of democracy, tolerance must become a daily guideline and community ethics.

It is time to re-evaluate and practice the value of tolerance.

That is why Hong Se-hwa devotes a significant portion of this book to explaining tolerance under the title “Boron,” and why we need to reread this book now.

A true friend of the marginalized and an eternal outsider

The one book that became Hong Se-hwa's starting point

Hong Se-hwa returned to Korea permanently after publishing “I am a Taxi Driver in Paris” about 10 years ago.

The joy of returning to his homeland was short-lived, as he refused to adapt to the Korean society he was re-introduced to.

As an awakened critic, he practiced the spirit of tolerance he preached throughout his life.

As a journalist, politician, and social activist, he has boldly criticized the hypocrisy and self-righteousness of vested interests regardless of whether they are conservative or progressive.

Even if it was an opinion that was not welcomed by the majority, I did not bend if it contributed to creating a more equal and inclusive society.

It was a life that inevitably led him to become an 'outsider', but he kept heading towards lower and more remote places.

We stood together as friends of those who were pushed out there, refugees, sexual minorities, women, the disabled, irregular workers, and the poor.

He was a thinker and practitioner who diligently worked toward the ideals of true freedom, equality, and solidarity.

He was an adult of the time who silently showed us at the forefront what kind of world we should open.

Considering that before he went into exile, he was a member of the elite and a member of the establishment, aka the 'KS' mark, having graduated from Gyeonggi High School and Seoul National University in Korea, this is a truly surprising move.

It would not be an exaggeration to say that it was thanks to his 20 years in Paris that he, with such a background, was able to live as an 'evangelist of tolerance', an 'outsider', and a 'simple free man' without taking advantage of those in power.

It was probably possible because I never forgot the days when I had to endure the “bitterness of ‘survival’” (p. 114) while unexpectedly working as a taxi driver, when all my previous backgrounds became meaningless and I had to confront a different society with my bare body.

The customers who treated foreign taxi drivers who struggled with French as equals, the fellow taxi drivers who taught them the meaning of everyday solidarity, the free-spirited Parisians on the streets who laughed, chatted, put their arms around each other, and protested… This book contains the people, scenes, and anecdotes that completely changed his life, leaving him with unforgettable surprises, emotions, and bitterness.

Let's follow the story of Hong Se-hwa, who opens the book "I am a Taxi Driver in Paris", the one that became his starting point, and starts his journey by saying, "Come to Paris" (page 13).

Tolerance will become a living reality, not just a slogan, and will serve as a milestone for us as we navigate an era of division and disconnection.

* A memorial service and memorial cultural festival to commemorate the first anniversary of the passing of the late Hong Se-hwa and to remember his spirit together will be held on April 18, 2025 (Inquiries: Hong Se-hwa 1st Anniversary Memorial Committee 02-6004-2000).

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: April 11, 2025

- Page count, weight, size: 420 pages | 434g | 142*208*20mm

- ISBN13: 9788936480783

- ISBN10: 8936480782

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)