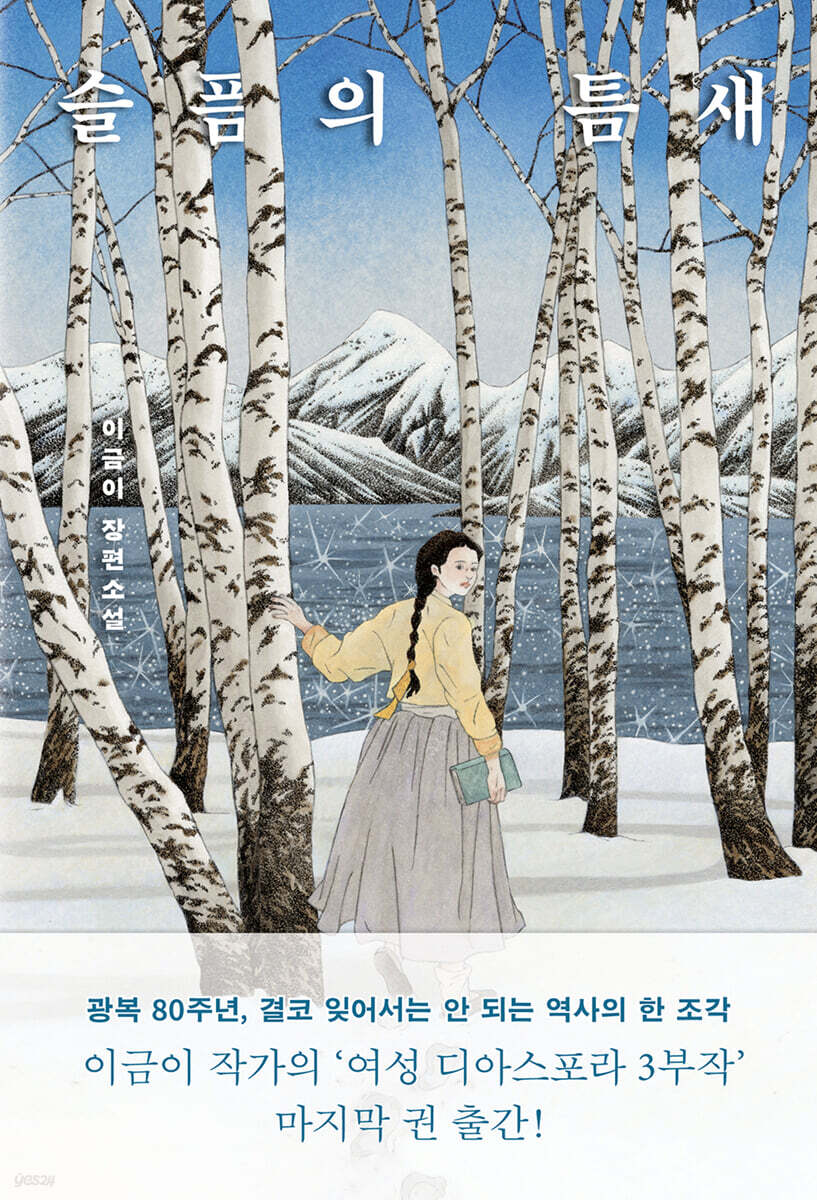

The Gap of Sorrow

|

Description

Book Introduction

- A word from MD

-

The final installment of the trilogy on the female diaspora during the Japanese colonial period.On the 80th anniversary of liberation, the story of a woman who came back to life from the cracks of forgotten history.

『The Gap of Sorrow』.

The novel depicts the life of 'Dan-ok', who never gave in and survived despite her fate of changing her name and nationality several times.

A story of Sakhalin in the 1940s, restoring the voice of history we had forgotten through her life and the lives of those around her.

August 13, 2025. Novel/Poetry PD Kim Yu-ri

2018 IBBY Honor List Selection

Finalists for the 2024 Hans Christian Andersen Award in the Writing Category

The final volume of author Lee Geum-i's "Japanese Colonial Women's Diaspora Trilogy" has been published!

On the 80th anniversary of liberation, the voice of our history that the nation and society must remember.

The story of Sakhalin Koreans, who lived their lives more earnestly than anyone else, begins here.

There are people who went to Sakhalin in 1940 during the Japanese colonial period, deceived by Japan's promise of jobs.

It was a journey where I thought I would only be away for a short time during the contract period to earn money to feed my family and send my children to school.

However, fatal accidents occurred frequently in Sakhalin coal mines, and unlike what was expected, workers were only paid small amounts after being forced to save money.

The whereabouts of the saved money were difficult to ascertain as the contract period was forcibly extended.

Those who went to Sakhalin under the 'National Mobilization Law' that Japan implemented in Korea were forced to live as stateless people under the rule of Japan and the Soviet Union, waiting for the day they could return to their homeland.

The story of Danok in the novel is about the experiences of the first generation of Koreans in Sakhalin.

Published to commemorate the 80th anniversary of liberation, "The Gap of Sorrow" deeply captures a part of our history that must never be forgotten.

Joo Dan-ok, Yakemoto Tamako, Joo Dan-ok again, and Olga Song.

It unfolds the life of 'Joo Dan-ok', a person who, over the course of 80 years, changed her name and nationality several times, was betrayed by her country countless times, and yet, more desperately than anyone else, carved out her own path in life.

The story of Sakhalin Koreans, who embraced history with their whole being, makes us reexamine the meaning and reason for the existence of our nation today.

Finalists for the 2024 Hans Christian Andersen Award in the Writing Category

The final volume of author Lee Geum-i's "Japanese Colonial Women's Diaspora Trilogy" has been published!

On the 80th anniversary of liberation, the voice of our history that the nation and society must remember.

The story of Sakhalin Koreans, who lived their lives more earnestly than anyone else, begins here.

There are people who went to Sakhalin in 1940 during the Japanese colonial period, deceived by Japan's promise of jobs.

It was a journey where I thought I would only be away for a short time during the contract period to earn money to feed my family and send my children to school.

However, fatal accidents occurred frequently in Sakhalin coal mines, and unlike what was expected, workers were only paid small amounts after being forced to save money.

The whereabouts of the saved money were difficult to ascertain as the contract period was forcibly extended.

Those who went to Sakhalin under the 'National Mobilization Law' that Japan implemented in Korea were forced to live as stateless people under the rule of Japan and the Soviet Union, waiting for the day they could return to their homeland.

The story of Danok in the novel is about the experiences of the first generation of Koreans in Sakhalin.

Published to commemorate the 80th anniversary of liberation, "The Gap of Sorrow" deeply captures a part of our history that must never be forgotten.

Joo Dan-ok, Yakemoto Tamako, Joo Dan-ok again, and Olga Song.

It unfolds the life of 'Joo Dan-ok', a person who, over the course of 80 years, changed her name and nationality several times, was betrayed by her country countless times, and yet, more desperately than anyone else, carved out her own path in life.

The story of Sakhalin Koreans, who embraced history with their whole being, makes us reexamine the meaning and reason for the existence of our nation today.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Part 1

Crossing three seas

1943

White night, black day

1943

warm winter

1943

cool summer

1944

Those left behind

1944

hot summer

1945

procession

1945

Uglegorsk

1946

Part 2

return ship

1946~1949

Again, start

1949

marriage proposal

1950

marriage

1951

stateless person

1957

Part 3

select

1958

Fork in the Road 1

1960

Fork in the Road 2

1961

frozen ground

1963

The Last Feast

1964

The Gap of Sorrow

1966

Part 4

Danok, Tamako, Olga

1988

collapsing dam

1992

Root 1

1995

Root 2

1996

August 15, 1945

1999

half of the heart

2000

testament

2025

Author's Note

References

Crossing three seas

1943

White night, black day

1943

warm winter

1943

cool summer

1944

Those left behind

1944

hot summer

1945

procession

1945

Uglegorsk

1946

Part 2

return ship

1946~1949

Again, start

1949

marriage proposal

1950

marriage

1951

stateless person

1957

Part 3

select

1958

Fork in the Road 1

1960

Fork in the Road 2

1961

frozen ground

1963

The Last Feast

1964

The Gap of Sorrow

1966

Part 4

Danok, Tamako, Olga

1988

collapsing dam

1992

Root 1

1995

Root 2

1996

August 15, 1945

1999

half of the heart

2000

testament

2025

Author's Note

References

Detailed image

Into the book

To Danok's eyes, the island's shape, with its dorsal and caudal fins, resembled a fish trying to swim farther.

The fish-shaped island was divided into north and south, with only the south side painted red.

That was Hwatae.

Hwa-tae was a place where my father was, where I could eat three meals a day, and where I could go to school to my heart's content.

It seemed as if, once he got there, that big, mysterious fish would carry him on its back and take him to a wider, more wonderful world.

--- p.17

Sakhalin was originally Russian land.

After winning the war against Russia in 1905, Japan took over the southern part of Sakhalin and began to rule it.

Japan named southern Sakhalin Karafuto after the name used by the indigenous Ainu people, and Koreans called it Hwatae, pronounced in Chinese characters.

It meant an island with many birch trees.

--- p.20

Dan-ok, who was still unfamiliar with everything, immediately became close with Yukie, who had been an outcast both in the school and in the residential area because her mother had remarried a Korean man.

The two of them walked together like shadows on their way to and from school.

In Danok's classroom, there was an Ainu child named Chikapa.

The Ainu were the indigenous people who lived here before Russia and Japan took over Sakhalin.

However, the Chikapa were ignored and ridiculed by the Japanese who took their land.

Dan-ok, the only Korean in the class, would often feel relieved at the thought that if Yukie hadn't been there, she would have ended up in the same situation as Chikapa.

--- p.36

The Soviet army ordered the people gathered at the port to return to their homes.

People were arrested or shot to death for protesting violently.

The Japanese returned as ordered, but most Koreans could not turn back.

Some people even went crazy or committed suicide while waiting for the return ship to arrive near the port.

--- pp.123-124

He was only 22 months old when he left Korea.

The baby, who had no control over his own life, was sleeping soundly in his mother's lap.

Yet, Yeongbok felt as if he had actually seen the moon shining coldly like a piece of ice in the dawn sky that day.

The image of his mother, older brother, and older sister carrying him on their backs came to mind, and he seemed to even hear the footsteps of his grandfather who followed him to help him carry his luggage.

It was because I grew up receiving my mother's recurring memories.

Yeongbok lived with his mother's pain and longing for his hometown engraved in his heart as if it were his own.

--- p.235

The scenery seen from the sky over Sakhalin was completely white, but there was no snow in Seoul.

No snow in late December.

Danok was amazed by that, but there was something even more unbelievable.

“It took less than three hours to get here, a journey that took over ten days.”

Danok's journey to Sakhalin via Japan, taking turns taking trains and boats, was still vivid in her mind.

Yukie smiled and said to Dan-ok, who was looking disappointed.

“It didn’t take less than three hours, it took 50 years?”

The fish-shaped island was divided into north and south, with only the south side painted red.

That was Hwatae.

Hwa-tae was a place where my father was, where I could eat three meals a day, and where I could go to school to my heart's content.

It seemed as if, once he got there, that big, mysterious fish would carry him on its back and take him to a wider, more wonderful world.

--- p.17

Sakhalin was originally Russian land.

After winning the war against Russia in 1905, Japan took over the southern part of Sakhalin and began to rule it.

Japan named southern Sakhalin Karafuto after the name used by the indigenous Ainu people, and Koreans called it Hwatae, pronounced in Chinese characters.

It meant an island with many birch trees.

--- p.20

Dan-ok, who was still unfamiliar with everything, immediately became close with Yukie, who had been an outcast both in the school and in the residential area because her mother had remarried a Korean man.

The two of them walked together like shadows on their way to and from school.

In Danok's classroom, there was an Ainu child named Chikapa.

The Ainu were the indigenous people who lived here before Russia and Japan took over Sakhalin.

However, the Chikapa were ignored and ridiculed by the Japanese who took their land.

Dan-ok, the only Korean in the class, would often feel relieved at the thought that if Yukie hadn't been there, she would have ended up in the same situation as Chikapa.

--- p.36

The Soviet army ordered the people gathered at the port to return to their homes.

People were arrested or shot to death for protesting violently.

The Japanese returned as ordered, but most Koreans could not turn back.

Some people even went crazy or committed suicide while waiting for the return ship to arrive near the port.

--- pp.123-124

He was only 22 months old when he left Korea.

The baby, who had no control over his own life, was sleeping soundly in his mother's lap.

Yet, Yeongbok felt as if he had actually seen the moon shining coldly like a piece of ice in the dawn sky that day.

The image of his mother, older brother, and older sister carrying him on their backs came to mind, and he seemed to even hear the footsteps of his grandfather who followed him to help him carry his luggage.

It was because I grew up receiving my mother's recurring memories.

Yeongbok lived with his mother's pain and longing for his hometown engraved in his heart as if it were his own.

--- p.235

The scenery seen from the sky over Sakhalin was completely white, but there was no snow in Seoul.

No snow in late December.

Danok was amazed by that, but there was something even more unbelievable.

“It took less than three hours to get here, a journey that took over ten days.”

Danok's journey to Sakhalin via Japan, taking turns taking trains and boats, was still vivid in her mind.

Yukie smiled and said to Dan-ok, who was looking disappointed.

“It didn’t take less than three hours, it took 50 years?”

--- pp.379-380

Publisher's Review

For over 40 years, history has consistently focused on those who are not remembered.

The final volume of author Lee Geum-i's "Japanese Colonial Women's Diaspora Trilogy" has been published!

Author Lee Geum-i, who began her career by winning the Saebyeot Literary Award in 1984, has been writing for 41 years.

He has established himself as a representative Korean artist by publishing works that deeply examine the lives of contemporary children and adolescents.

For the author, who has consistently taken an interest in those whom history has forgotten, and has continued to shed light on them through direct reporting and literature, the "Trilogy on the Korean Women's Diaspora during the Japanese Colonial Period" was a task that felt like an inevitable necessity.

The author's first historical novel, "Can't I Go There?" (Sageseul Publishing, 2016), tells the story of a character the author has harbored in his heart for ten years.

The story of two girls born with different social status during the Japanese colonial period who independently navigate their own destinies resonated deeply with readers not only in Korea but also overseas, with the rights to the book being exported to English, Japanese, Arabic, and Italian.

For this work, author Lee Geum-i was selected for the 2018 IBBY Honor List.

In addition, he became the first Korean writer to be nominated for the Hans Christian Andersen Award in the writing category in 2024, solidifying the status of Korean literature with the comment that he showed "how the canon of children's and young adult literature should be in harmony with the contemporary times."

The 'Japanese Colonial Women's Diaspora Trilogy', which began with 'Can't I Go There?', is now complete after nine years, following the publication of 'Aloha, My Mothers' (Changbi, 2020) and the final work, 'The Gap of Sorrow'.

Published to commemorate the 80th anniversary of liberation, "The Gap of Sorrow" is not a simple historical novel; it is a tribute to the turbulent history of Sakhalin Koreans who were forced to leave their homeland, and a testimony to those who lived their lives more earnestly than anyone else.

“August 15, 1945 was the day our country was liberated,

For Sakhalin Koreans, it was a day when they lost their hometown and family.”

The novel begins in March 1943, with Danok leaving her hometown of Daraeul for South Sakhalin (Hwatae).

Not knowing that it was part of the 'National Mobilization Law' that Japan implemented in Joseon, the father who went to the Hwatae coal mine because he heard that he could make money there, the family who went on a long journey to find his father, and the other family members who remained in their hometown.

No one knew that the journey they set out on that day would lead to an eternal separation.

The reunion with his father in Hwatae, where he barely managed to arrive, was short-lived, as in 1944, under the order of "relocation" to the mainland, Japan double-conscripted the laborers, separating them from their families once again.

The story of Danok's family being helplessly separated is not limited to the novel.

This is the true story of the first generation of Koreans in Sakhalin during the Japanese colonial period in the late 1930s.

South Sakhalin, where Sakhalin Koreans were forced to work, was originally Russian territory.

After winning the Russo-Japanese War in 1905, Japan took over control of southern Sakhalin and ruled it for 40 years.

At that time, Japan named South Sakhalin Karafuto after the name the indigenous people used, and Koreans called it Hwatae using the Chinese characters.

However, in 1945, with the outbreak of the Soviet-Japanese War, South Sakhalin came under Soviet rule again.

During the several changes of ruling system, the Koreans of Sakhalin were neither Japanese, Soviet, nor, of course, Korean.

On August 15, 1945, news arrived that their homeland had been liberated from Japan, but the lives of Sakhalin Koreans did not change.

All that came to the Koreans waiting for a ship to return home at the port was the Soviet military's order to return to their homes, along with the false accusation and persecution of being Japanese spies.

For Sakhalin Koreans who had lived as stateless people for fear of causing trouble when returning home, August 15th was once again a day of betrayal by their homeland.

During those painful times, Koreans began to bury in their hearts the memories of their homeland and their families, whom they could not return to, and began to live in solidarity with the people they met in Sakhalin.

Even in the face of an irreversible history, the reality of having to feed family members and support growing children comes every day without fail, so first-generation Koreans could not remain in sorrow.

The lives of women who never lose their humanity in any situation

It shows how strong and wonderful the path we take together, cherishing and supporting each other.

Chiyo, who took care of the livelihood of Deokchun, who lost Manseok due to double conscription, and Jeongman, who injured his leg in a coal mine accident.

The novel focuses on the lives of women at the time, as their daughters, Danok and Yukie, inherit the land they had built, having done whatever it took to survive.

Just as previous generations have, the next generation of women, burdened with countless betrayals and pessimism from both their homeland and foreign countries, will once again take unstoppable steps toward an uncertain future.

The novel unfolds the lives of the women who stand on that path from 1940 to 2025.

Among the laborers forcibly conscripted to Sakhalin at the time, there were not only Koreans.

Except for a few managers, Japanese workers were treated similarly to Koreans.

During the Japanese colonial period, in a coal mining town with many Koreans, Yukiene was a being that could never be fully integrated.

Yukie, a Japanese woman, had to live as a foreigner in a different sense from Danok.

Between 1946 and 1949, Japan restricted the repatriation of its citizens from Sakhalin to those with Japanese nationality.

Although they were one family, Yukiene was only able to return to Chiyo and Yuki, who were Japanese, and the two younger siblings born between Chiyo and Jeongman were also not included.

In this situation, Yukie feels a sense of family-like bond and affection towards Danok, who is her peer.

In that land where no one was free from discrimination, Danok and Yukie were neither Korean nor Japanese to each other.

At some point, the time they spent in Sakhalin surpassed the time they spent in Korea, and for them, Sakhalin became a place where they could live rather than a foreign country they had to leave behind.

There, the two spend their childhood together, share secrets they cannot tell their parents or siblings, and share moments of laughter and tears as they get married and raise children.

The lives of the women in the novel are shaky, but they never lose their humanity in any situation, leaving a deep impression.

The two families, who left their ethnicity and nationality behind and began living together as a new community, show how strong and wonderful the path forward is for social minorities to cherish and support each other.

The meaning of literature that connects the past and the future

A shared sense of responsibility for “history as a story in which we are all involved”

In the novel, the characters are not simply individuals placed in history, but stand as beings who have lived their lives with dignity.

The work covers the lives of two families and more than twenty characters.

Although their reasons for coming to Sakhalin are similar, as time passes, each character takes a different direction.

Danok, who came to Sakhalin as a child, holds onto memories of her homeland, but does not want to leave Sakhalin, where her children and grandchildren are.

On the other hand, his younger brother Gwangbok, who was born in Sakhalin, wants to live in Korea, a country he has never been to.

Although Yukie had several opportunities to return to Japan, she remained in Sakhalin, wanting to live in the place where she had put down roots.

In this way, the characters in 『The Gap of Sorrow』 clearly reveal their own worries about life, and each is conveyed to the reader with a lively appearance.

The author was always on guard against making quick judgments about the characters, so he personally went to Sakhalin to hear the voices of Koreans and toured the region that served as the setting for the work.

This novel, which began with a sentence that came to the author out of the blue in the summer of 2018, was finally completed seven years later.

The moment Sakhalin was mentioned as a travel destination, my heart raced.

At that time, the thought of "Can't I go there?" was in my heart.

The reason he, who ended up dead in the novel, is still remembered is probably because he had a story to tell.

The moment Taesul and the unknown space of Sakhalin met, a single sentence swept through me like an electric current.

Taesul, who was thought to be dead, was living in Sakhalin. _Author's Note

The journey to Sakhalin led by 'Tae-sul', a character in the author's first historical novel, led the author to meet a girl named 'Dan-ok'.

The author walked through the novel to the end with Danok, who had become more vivid in his mind than Taesul, and completed the work after seven years.

In the process, the author discarded all of the drafts he had written, rewrote the novel, and spent time listening more closely to the characters' voices.

As a result, as novelist Kang Hwa-gil said, “This time, author Lee Geum-i has found the entrance again,” the author has once again created a path connecting the past and the present.

Experiencing the past through literature reminds us that the world we live in is not just ours, but a place connected to others.

That feeling holds us accountable for never being free from any past.

This sense of shared responsibility allows us to approach the story of Sakhalin Koreans, as sociologist Cho Hyung-geun puts it, “not as the interesting story of others, but as a history in which we are all implicated.”

We are thus connected, both through debt and through light, between the past and the future.

"The Gap of Sorrow" illuminates a part of our history that has been neglected by the nation and society, while genuinely demonstrating the significance of literature as a bridge between the past and the future.

“The reason they came to live in Sakhalin was because of its sad history, but they did not remain in that sadness. Instead, they found a ‘gap in the sadness’ and lived passionately and proudly.

Neither the national history of Korea, nor the national history of Japan, nor the vast history of the Soviet Union and Russia can fully encompass their lives.

“They are marginal people who live in a small niche, but how splendid and majestic that niche is.” _Cho Hyeong-geun (sociologist)

*Characters

Deokchun: Danok's mother.

In 1943, she went to Sakhalin with her three children, Seongbok, Danok, and Yeongbok, to meet her husband.

Manseok: Danok's father.

In 1940, he was forced to work in the Sakhalin coal mines, and in 1944, he was separated from his family again due to double conscription.

Danok: Born in 1931, she lived her entire life in Sakhalin, where she went to see her father.

The names have been changed to Danok, Tamako, and Olga Song.

Chiyo: Yukie's mother.

She sends off her ex-husband Hideo due to the aftereffects of a coal mining accident and remarries Jeong-man.

Jeongman: One of Manseok's sworn brothers.

Yukie's stepfather.

He left his wife and daughter in Joseon and came to Sakhalin alone as a forced laborer in a coal mine.

Yukie: A friendship that is second to none with Dan-ok.

Born in 1932, he lives with a Japanese mother and a remarried Korean father.

Taesul: Manseok and Jeongman's sworn brothers.

Jinsoo: Danok's husband.

I am from Jeju Island and live in Jeju Island Village, Sakhalin.

Seongbok: Danok's older brother.

Contact was lost on the way to Sakhalin in 1943.

Yeongok: Danok's younger sister.

He remains with his grandparents in his hometown of Daraeul and loses contact.

Yeongbok: Danok's younger brother.

At the age of 22 months, he came to Sakhalin in his mother's arms.

Hae-ok: Dan-ok's younger sister.

Born in Sakhalin in 1943, her name was changed to Umiko, Haeja, and Haeok.

Gwangbok: Danok's youngest brother.

Born in Sakhalin in 1945.

Yongjae, Seongjae: Yukie's younger brothers.

The final volume of author Lee Geum-i's "Japanese Colonial Women's Diaspora Trilogy" has been published!

Author Lee Geum-i, who began her career by winning the Saebyeot Literary Award in 1984, has been writing for 41 years.

He has established himself as a representative Korean artist by publishing works that deeply examine the lives of contemporary children and adolescents.

For the author, who has consistently taken an interest in those whom history has forgotten, and has continued to shed light on them through direct reporting and literature, the "Trilogy on the Korean Women's Diaspora during the Japanese Colonial Period" was a task that felt like an inevitable necessity.

The author's first historical novel, "Can't I Go There?" (Sageseul Publishing, 2016), tells the story of a character the author has harbored in his heart for ten years.

The story of two girls born with different social status during the Japanese colonial period who independently navigate their own destinies resonated deeply with readers not only in Korea but also overseas, with the rights to the book being exported to English, Japanese, Arabic, and Italian.

For this work, author Lee Geum-i was selected for the 2018 IBBY Honor List.

In addition, he became the first Korean writer to be nominated for the Hans Christian Andersen Award in the writing category in 2024, solidifying the status of Korean literature with the comment that he showed "how the canon of children's and young adult literature should be in harmony with the contemporary times."

The 'Japanese Colonial Women's Diaspora Trilogy', which began with 'Can't I Go There?', is now complete after nine years, following the publication of 'Aloha, My Mothers' (Changbi, 2020) and the final work, 'The Gap of Sorrow'.

Published to commemorate the 80th anniversary of liberation, "The Gap of Sorrow" is not a simple historical novel; it is a tribute to the turbulent history of Sakhalin Koreans who were forced to leave their homeland, and a testimony to those who lived their lives more earnestly than anyone else.

“August 15, 1945 was the day our country was liberated,

For Sakhalin Koreans, it was a day when they lost their hometown and family.”

The novel begins in March 1943, with Danok leaving her hometown of Daraeul for South Sakhalin (Hwatae).

Not knowing that it was part of the 'National Mobilization Law' that Japan implemented in Joseon, the father who went to the Hwatae coal mine because he heard that he could make money there, the family who went on a long journey to find his father, and the other family members who remained in their hometown.

No one knew that the journey they set out on that day would lead to an eternal separation.

The reunion with his father in Hwatae, where he barely managed to arrive, was short-lived, as in 1944, under the order of "relocation" to the mainland, Japan double-conscripted the laborers, separating them from their families once again.

The story of Danok's family being helplessly separated is not limited to the novel.

This is the true story of the first generation of Koreans in Sakhalin during the Japanese colonial period in the late 1930s.

South Sakhalin, where Sakhalin Koreans were forced to work, was originally Russian territory.

After winning the Russo-Japanese War in 1905, Japan took over control of southern Sakhalin and ruled it for 40 years.

At that time, Japan named South Sakhalin Karafuto after the name the indigenous people used, and Koreans called it Hwatae using the Chinese characters.

However, in 1945, with the outbreak of the Soviet-Japanese War, South Sakhalin came under Soviet rule again.

During the several changes of ruling system, the Koreans of Sakhalin were neither Japanese, Soviet, nor, of course, Korean.

On August 15, 1945, news arrived that their homeland had been liberated from Japan, but the lives of Sakhalin Koreans did not change.

All that came to the Koreans waiting for a ship to return home at the port was the Soviet military's order to return to their homes, along with the false accusation and persecution of being Japanese spies.

For Sakhalin Koreans who had lived as stateless people for fear of causing trouble when returning home, August 15th was once again a day of betrayal by their homeland.

During those painful times, Koreans began to bury in their hearts the memories of their homeland and their families, whom they could not return to, and began to live in solidarity with the people they met in Sakhalin.

Even in the face of an irreversible history, the reality of having to feed family members and support growing children comes every day without fail, so first-generation Koreans could not remain in sorrow.

The lives of women who never lose their humanity in any situation

It shows how strong and wonderful the path we take together, cherishing and supporting each other.

Chiyo, who took care of the livelihood of Deokchun, who lost Manseok due to double conscription, and Jeongman, who injured his leg in a coal mine accident.

The novel focuses on the lives of women at the time, as their daughters, Danok and Yukie, inherit the land they had built, having done whatever it took to survive.

Just as previous generations have, the next generation of women, burdened with countless betrayals and pessimism from both their homeland and foreign countries, will once again take unstoppable steps toward an uncertain future.

The novel unfolds the lives of the women who stand on that path from 1940 to 2025.

Among the laborers forcibly conscripted to Sakhalin at the time, there were not only Koreans.

Except for a few managers, Japanese workers were treated similarly to Koreans.

During the Japanese colonial period, in a coal mining town with many Koreans, Yukiene was a being that could never be fully integrated.

Yukie, a Japanese woman, had to live as a foreigner in a different sense from Danok.

Between 1946 and 1949, Japan restricted the repatriation of its citizens from Sakhalin to those with Japanese nationality.

Although they were one family, Yukiene was only able to return to Chiyo and Yuki, who were Japanese, and the two younger siblings born between Chiyo and Jeongman were also not included.

In this situation, Yukie feels a sense of family-like bond and affection towards Danok, who is her peer.

In that land where no one was free from discrimination, Danok and Yukie were neither Korean nor Japanese to each other.

At some point, the time they spent in Sakhalin surpassed the time they spent in Korea, and for them, Sakhalin became a place where they could live rather than a foreign country they had to leave behind.

There, the two spend their childhood together, share secrets they cannot tell their parents or siblings, and share moments of laughter and tears as they get married and raise children.

The lives of the women in the novel are shaky, but they never lose their humanity in any situation, leaving a deep impression.

The two families, who left their ethnicity and nationality behind and began living together as a new community, show how strong and wonderful the path forward is for social minorities to cherish and support each other.

The meaning of literature that connects the past and the future

A shared sense of responsibility for “history as a story in which we are all involved”

In the novel, the characters are not simply individuals placed in history, but stand as beings who have lived their lives with dignity.

The work covers the lives of two families and more than twenty characters.

Although their reasons for coming to Sakhalin are similar, as time passes, each character takes a different direction.

Danok, who came to Sakhalin as a child, holds onto memories of her homeland, but does not want to leave Sakhalin, where her children and grandchildren are.

On the other hand, his younger brother Gwangbok, who was born in Sakhalin, wants to live in Korea, a country he has never been to.

Although Yukie had several opportunities to return to Japan, she remained in Sakhalin, wanting to live in the place where she had put down roots.

In this way, the characters in 『The Gap of Sorrow』 clearly reveal their own worries about life, and each is conveyed to the reader with a lively appearance.

The author was always on guard against making quick judgments about the characters, so he personally went to Sakhalin to hear the voices of Koreans and toured the region that served as the setting for the work.

This novel, which began with a sentence that came to the author out of the blue in the summer of 2018, was finally completed seven years later.

The moment Sakhalin was mentioned as a travel destination, my heart raced.

At that time, the thought of "Can't I go there?" was in my heart.

The reason he, who ended up dead in the novel, is still remembered is probably because he had a story to tell.

The moment Taesul and the unknown space of Sakhalin met, a single sentence swept through me like an electric current.

Taesul, who was thought to be dead, was living in Sakhalin. _Author's Note

The journey to Sakhalin led by 'Tae-sul', a character in the author's first historical novel, led the author to meet a girl named 'Dan-ok'.

The author walked through the novel to the end with Danok, who had become more vivid in his mind than Taesul, and completed the work after seven years.

In the process, the author discarded all of the drafts he had written, rewrote the novel, and spent time listening more closely to the characters' voices.

As a result, as novelist Kang Hwa-gil said, “This time, author Lee Geum-i has found the entrance again,” the author has once again created a path connecting the past and the present.

Experiencing the past through literature reminds us that the world we live in is not just ours, but a place connected to others.

That feeling holds us accountable for never being free from any past.

This sense of shared responsibility allows us to approach the story of Sakhalin Koreans, as sociologist Cho Hyung-geun puts it, “not as the interesting story of others, but as a history in which we are all implicated.”

We are thus connected, both through debt and through light, between the past and the future.

"The Gap of Sorrow" illuminates a part of our history that has been neglected by the nation and society, while genuinely demonstrating the significance of literature as a bridge between the past and the future.

“The reason they came to live in Sakhalin was because of its sad history, but they did not remain in that sadness. Instead, they found a ‘gap in the sadness’ and lived passionately and proudly.

Neither the national history of Korea, nor the national history of Japan, nor the vast history of the Soviet Union and Russia can fully encompass their lives.

“They are marginal people who live in a small niche, but how splendid and majestic that niche is.” _Cho Hyeong-geun (sociologist)

*Characters

Deokchun: Danok's mother.

In 1943, she went to Sakhalin with her three children, Seongbok, Danok, and Yeongbok, to meet her husband.

Manseok: Danok's father.

In 1940, he was forced to work in the Sakhalin coal mines, and in 1944, he was separated from his family again due to double conscription.

Danok: Born in 1931, she lived her entire life in Sakhalin, where she went to see her father.

The names have been changed to Danok, Tamako, and Olga Song.

Chiyo: Yukie's mother.

She sends off her ex-husband Hideo due to the aftereffects of a coal mining accident and remarries Jeong-man.

Jeongman: One of Manseok's sworn brothers.

Yukie's stepfather.

He left his wife and daughter in Joseon and came to Sakhalin alone as a forced laborer in a coal mine.

Yukie: A friendship that is second to none with Dan-ok.

Born in 1932, he lives with a Japanese mother and a remarried Korean father.

Taesul: Manseok and Jeongman's sworn brothers.

Jinsoo: Danok's husband.

I am from Jeju Island and live in Jeju Island Village, Sakhalin.

Seongbok: Danok's older brother.

Contact was lost on the way to Sakhalin in 1943.

Yeongok: Danok's younger sister.

He remains with his grandparents in his hometown of Daraeul and loses contact.

Yeongbok: Danok's younger brother.

At the age of 22 months, he came to Sakhalin in his mother's arms.

Hae-ok: Dan-ok's younger sister.

Born in Sakhalin in 1943, her name was changed to Umiko, Haeja, and Haeok.

Gwangbok: Danok's youngest brother.

Born in Sakhalin in 1945.

Yongjae, Seongjae: Yukie's younger brothers.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: August 15, 2025

- Page count, weight, size: 448 pages | 128*188*30mm

- ISBN13: 9791169813839

- ISBN10: 1169813836

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)