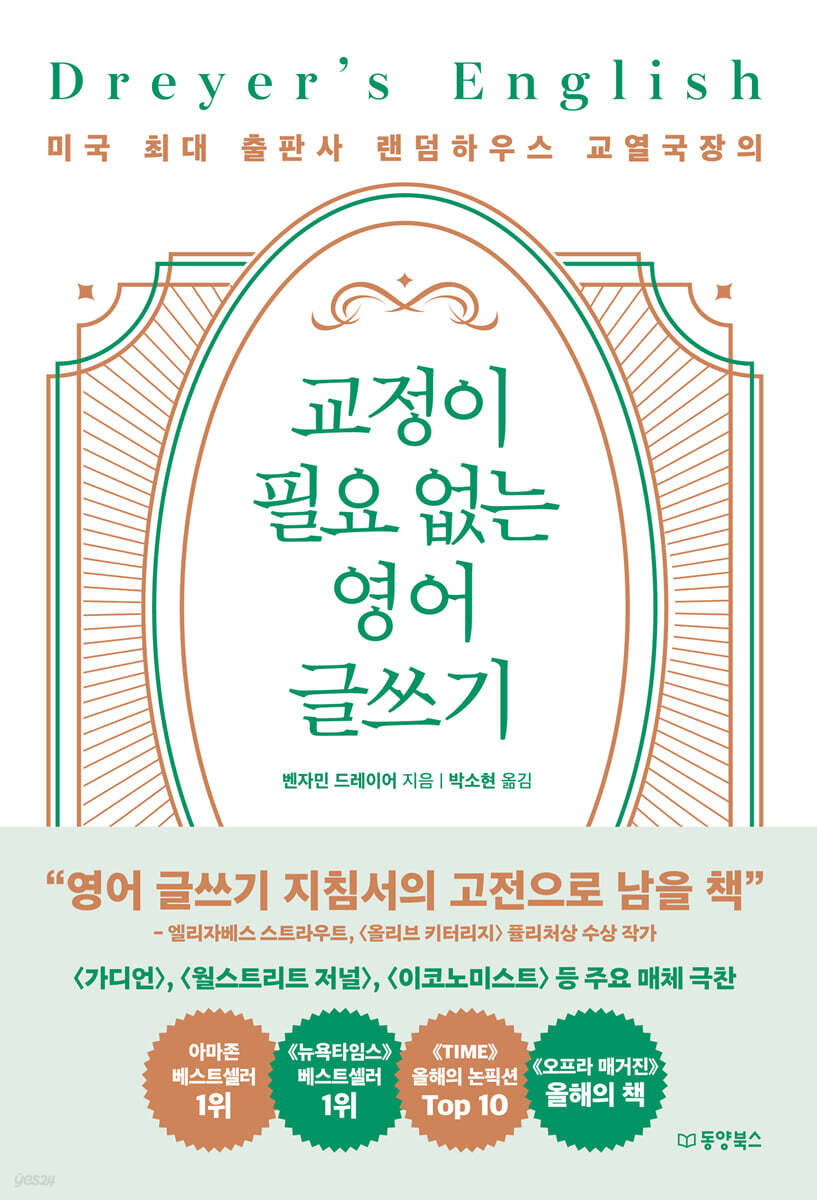

English writing that doesn't need proofreading

|

Description

Book Introduction

The head of the copyediting department at Random House, the largest publishing company in the United States

How to Proofread English

The author is a proofreader who has been editing the writings of leading American writers, including Pulitzer Prize-winning authors, for decades.

I have been following the rules of English writing faithfully for so long that I sometimes think, “Half my life is spent removing commas, and the other half is spent putting them back in the right place.” However, I am not a boring, principled person who remains a “backroom old man in the proofreading department” or an “old-fashioned proofreader” who clings to outdated rules.

As a social media influencer who is famous for sharing real-time tips on how to flexibly apply English usage and writing principles, it is almost the opposite.

He says that the best way to write is to boldly break the rules that are taboo in writing guides that boast of orthodoxy and authority and to write with the artist's skill as a writer (especially when it comes to novels).

Why? Because language is constantly evolving.

The author, who has observed the changing landscape from the front lines of the publishing industry, which can be said to be the most sensitive to language, is a living witness who has personally experienced that while some principles have become obsolete over time, others still must be upheld.

Moreover, with the advent of the online age, writing principles and English usage are changing more rapidly.

The author clearly organizes the principles of proper writing that must be maintained until the end, rules that can now be discarded, usages that have been incorrectly used, expressions that are still confusing, and newly introduced grammar. With abundant examples drawn from history, popular culture, literary works, and social media, and explanations that shine with his characteristic sense of humor, he has published a practical guide to English writing that anyone can enjoy reading.

How to Proofread English

The author is a proofreader who has been editing the writings of leading American writers, including Pulitzer Prize-winning authors, for decades.

I have been following the rules of English writing faithfully for so long that I sometimes think, “Half my life is spent removing commas, and the other half is spent putting them back in the right place.” However, I am not a boring, principled person who remains a “backroom old man in the proofreading department” or an “old-fashioned proofreader” who clings to outdated rules.

As a social media influencer who is famous for sharing real-time tips on how to flexibly apply English usage and writing principles, it is almost the opposite.

He says that the best way to write is to boldly break the rules that are taboo in writing guides that boast of orthodoxy and authority and to write with the artist's skill as a writer (especially when it comes to novels).

Why? Because language is constantly evolving.

The author, who has observed the changing landscape from the front lines of the publishing industry, which can be said to be the most sensitive to language, is a living witness who has personally experienced that while some principles have become obsolete over time, others still must be upheld.

Moreover, with the advent of the online age, writing principles and English usage are changing more rapidly.

The author clearly organizes the principles of proper writing that must be maintained until the end, rules that can now be discarded, usages that have been incorrectly used, expressions that are still confusing, and newly introduced grammar. With abundant examples drawn from history, popular culture, literary works, and social media, and explanations that shine with his characteristic sense of humor, he has published a practical guide to English writing that anyone can enjoy reading.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Introduction --- 8

Part 1: The Basics of English Writing 1

CHAPTER 1 How to Create Concise English --- 20

CHAPTER 2: Principles and Non-Principles of English Writing --- 23

CHAPTER 3 67 Ways to Use Punctuation Marks ?? 40

CHAPTER 4 How to Write Numbers in English --- 99

CHAPTER 5: How to Write Foreign Languages and Loanwords --- 107

CHAPTER 6 Grammar Errors That Hurt Sentences --- 119

CHAPTER 7: The Basics of Writing English Novels --- 141

Part 2: The Basics of English Writing 2

CHAPTER 8: English Words Everyone Misuses at Least Once --- 170

CHAPTER 9: Likes and Dislikes of English Word Usage --- 195

CHAPTER 10: English Words That Confuse Even Writers --- 219

CHAPTER 11 Proper Nouns Even Proofreaders Get Wrong --- 280

CHAPTER 12: Tautological Expressions That Ruin Your Writing --- 326

CHAPTER 13 Seemingly Minor, but Crucial, Proofreading Tips --- 341

Outgoing Words --- 359

English Proofreaders' Favorite Sites --- 360

Part 1: The Basics of English Writing 1

CHAPTER 1 How to Create Concise English --- 20

CHAPTER 2: Principles and Non-Principles of English Writing --- 23

CHAPTER 3 67 Ways to Use Punctuation Marks ?? 40

CHAPTER 4 How to Write Numbers in English --- 99

CHAPTER 5: How to Write Foreign Languages and Loanwords --- 107

CHAPTER 6 Grammar Errors That Hurt Sentences --- 119

CHAPTER 7: The Basics of Writing English Novels --- 141

Part 2: The Basics of English Writing 2

CHAPTER 8: English Words Everyone Misuses at Least Once --- 170

CHAPTER 9: Likes and Dislikes of English Word Usage --- 195

CHAPTER 10: English Words That Confuse Even Writers --- 219

CHAPTER 11 Proper Nouns Even Proofreaders Get Wrong --- 280

CHAPTER 12: Tautological Expressions That Ruin Your Writing --- 326

CHAPTER 13 Seemingly Minor, but Crucial, Proofreading Tips --- 341

Outgoing Words --- 359

English Proofreaders' Favorite Sites --- 360

Detailed image

Into the book

The proofreader went far beyond correcting typos, correcting punctuation, or correcting subject-verb agreement.

Most of the time—almost consistently—I was digging deeper into the author's writing, more carefully and from a more objective perspective.

I eliminated unnecessary words, inserted words here and there in overly dense sentences, rearranged paragraphs to make the argument more solid, and caught the author's overuse of adjectives and adverbs.

It was also the proofreader's job to add comments that the sentences were somewhat awkward (write "To the author: AU: Isn't this awkward?" in the margin) or that the expressions were tired and hackneyed ("To the author: Isn't this a cliché?").

In cases where the same point has already been made countless times or is so obvious that it doesn't need to be made at all, I've sometimes just drawn a red line through the entire sentence and written in the margin—though I thought it was overreaching—"To the author: We all know this."

--- p.

11~12

Let's try to last a week without using the following words.

very rather really quite in fact just so pretty of course surely that said actually

If you can get by without using these expressions, which fall under the category of "useless emphasis and vocal stimuli," on weekdays—I won't tell you not to use them when you speak.

If that were the case, most people, especially the British, would be dumb—by the end of the week, their writing skills would have improved significantly.

Well, fine, feel free to use it.

If every time you try to write a sentence, the pen in your hand won't budge.

But if you've written it, go back and delete it.

Get rid of them all, without leaving a single one behind.

Don't even think about leaving the last one behind, saying it looks cute or pitiful.

If the sentence you delete feels empty, find a more powerful and better expression that will convey what you want to say more effectively.

--- pp.

20~21

As much as I love good rules, I'm also a believer in the mantra that "rules are meant to be broken."

But that's only after you've learned the rules.

Here, I'd like to look at what I consider to be the 'great nonrules of the English language'.

You may have encountered this before.

You probably learned this in school, but erase it from your mind now.

Because it is useless.

(syncopation)

But why call it "unprincipled"? In my view, it's unhelpful, unnecessarily restrictive, irresponsible, and completely useless.

Moreover, most of them are of questionable origin.

It's something that falls from the sky and is passed down, but eventually gains a certain level of trust and becomes fixed.

Despite years of desperate attempts by language experts to dispel them, these fictitious principles persist, enduring with a tenacity more tenacious than Keith Richards and Mick Jagger.

With a life force more tenacious than the combined ages of two elderly people.

One problem is that some of these were likely created with good intentions by so-called language experts, and eradicating them for that reason could be like trying to stop a dog from chasing its own tail.

I intend to deal with these irregularities in a neat and tidy manner.

Readers, you can happily bid farewell, confident that I have done thorough research. (Omitted) I must confess that a large part of my job as a proofreader is to help authors avoid being unfairly or justifiably nagged—and this is painful—by people who claim to know better and send angry emails to publishers.

Therefore, even if the origins are somewhat questionable, it is better to follow principles that are unlikely to cause harm.

Also, I warn you in advance that the nonsense I'll explain below is so utter nonsense that if you break it, some readers and online commenters who like to lecture you will be treated with contempt and treat your writing skills as inferior.

Whether you like it or not, betray these principles as if you were telling me to.

It goes without saying that it will be a lot of fun, and I will not spare my support from behind.

--- pp.

24~26

Are contractions not allowed in formal writing?

If you are a Martian who learned English as a foreign language, there is nothing wrong with following this rule.

However, there is no problem at all with the contractions that people use in everyday life, such as don't, can't, and wouldn't.

In fact, if you don't use abbreviations, your writing will usually feel stiff and unnatural.

However, the abbreviation "I'd've" and "should've" can be excessive only in non-light writing.

Since the apostrophe was created to be used in abbreviations, I hope that both the apostrophe and abbreviations will be used effectively.

And while we're on the topic of should've,

The original correct notation is should have (could have, would have, etc.).

But if you're not on the same level as Flannery O'Connor, Zora Neale Hurston, or William Faulkner, but want to add character to your characters' speech like them―(omitted)―I urge you to actively use should've, could've, would've, etc.

--- pp.

31~32

If it appears to be a question, but you don't actually intend to ask a question, don't hesitate to use a period.

In this case, it is considered a statement that does not require a response.

--- p.

44

One thing to note is that commas are not a panacea, much less consecutive commas.

There is a sentence, supposedly from The Times, which I often reluctantly quote in defense of the serial comma, and which I am now disgusted to read, but which I reluctantly quote again, because it shows so well that it is rather inadequate in defending the serial comma.

Well, I hope this is the last time you see it, even though it's unlikely.

Highlights of his global tour include encounters with Nelson Mandela, an 800-year-old demigod and a dildo collector.

Highlights of his world tour include a meeting with Nelson Mandela, an 800-year-old demigod and dildo collector.

What a coincidence! Some might find it amusing, thinking, "Nelson Mandela, an eight-hundred-year-old demigod, and a sex toy collector?"

--- p.

46

As a serial abuser of parenthetical phrases, I advise you not to overuse them.

Especially if the intention is to provoke forced laughter.

If there are too many useless, shy asides, it will sound like a fancy-dressed actor in a Restoration comedy, walking up to the spotlight, covering his mouth, and whispering directly to the audience.

If you talk to the audience that often, they will miss the point of the play.

--- p.

74

Let's take a quick look at the original text here [sic].

sic is Latin for thus, therefore, and accordingly—traditionally italicized and always enclosed in square brackets—and is used to indicate to the reader that a typographical error or other error in a quoted passage has been corrected to preserve the original text, and that the error is not the fault of the author who quoted it.

When quoting a 17th-century text that is full of archaic expressions, it is a good idea to include a note somewhere in the introduction, perhaps in a note or footnote, that the archaic passage has been copied in its entirety, without alteration.

Then there is no need for [sic] to run wild.

Except for the occasional use of [sic] when there are errors or peculiarities that could cause readers to misread or misunderstand.

Sometimes nonfiction writers secretly correct outdated spellings, typos, irregular capitalization, and odd or missing punctuation by quoting numerous passages from older sources or using unusual notation.

I'm not a huge proponent of this practice—it makes the writing less interesting than it used to be, given its quirky charm—but it's a different story when it comes to nonfiction aimed at a mass audience rather than academic books.

Again, if you intend to do so, please let your readers know in advance.

It's something a writer should do.

Don't ever—never—think of using [sic] to disparage a quote as nonsense.

If the intention is to attack the message of the quote itself, rather than just a spelling error.

I'd like to take this opportunity to poke fun at the original author's judgment, but I think if there's one person whose judgment seems questionable, it's the person quoting that quote.

That kind of writing is similar to a t-shirt that says "I'M WITH STUPID" and it makes you look that much more stupid.

--- pp.

77~78

Conversational language is indicated by quotation marks.

Authors who do not use quotation marks (E.

There are also L. Doctorow, William Gaddis, and Cormac McCarthy (who come to mind immediately), but I'll just say one thing.

To reach this level, you must become a master at freely moving between narrative and dialogue.

--- p.

80

I don't think it's going to offend anyone by italicizing six words in a row, but I'd advise against italicizing more than two sentences.

First of all, italics are tiring on the eyes.

Moreover, if there are several italicized paragraphs in a row, it reminds one of a dream scene, and readers tend to want to skip the dream scene.

--- p.

81

60.

If—and this advice applies only to somewhat lighter writing or conversation—a sentence is questionable in form but not semantically, end it with a period, not a question mark.

That's a good idea, don't you think? has a completely different meaning from That's a horrible idea, isn't it.

61.

Use exclamation marks sparingly.

If you use too many exclamation marks, it feels like you are being pushy and pushy, and you will eventually get tired of it.

Some authors recommend using no more than twelve exclamation points per book, while others insist on using no more than twelve in a lifetime.

62.

However, it is also irresponsible not to use exclamation marks when expressing an intense tone, such as "Your hair is on fire!"

A person whose hair is on fire wouldn't believe that.

"What a lovely day!" Even an exclamation like "What a beautiful day!" can sound sarcastic or create a gloomy atmosphere if it ends with a period instead of an exclamation point.

63.

Unless you're over ten and actively working as a comic book artist, don't end your sentences with two exclamation or question marks.

64

Let's not even mention !? or ?!

Because I will never use it.

--- pp.

96~97

It is not polite to start a sentence with an Arabic numeral.

An absolutely impossible example

1967 dawned clear and bright.

1967 dawned.

It's a little better, but it's not that good either.

Nineteen sixty-seven dawned clear and bright.

A better but tautological example

The year 1967 dawned clear and bright.

A much better way is this

Recast your sentence so it needn't begin with a year.

It shouldn't take you but a moment.

Rewrite the sentence without starting with the year.

It only takes a minute.

--- p.

102

No matter what principle you follow, the important thing when writing numbers is to be accurate.

For example, if the author wrote a sentence like, “Twelve useful rules for college graduates entering the job market,” the proofreader would count them first.

This is because it is common to say that you will list twelve things, but when you actually count them, there are only eleven.

It's easy to overlook, so be careful.

Otherwise, you'll just skip over it without even knowing that it says '67 ways to use punctuation marks' and only lists 66 of them.

I intentionally left out item 38 in chapter 3, did anyone notice?

--- p.

106

The real debate in this regard is theater.

It's been around long enough that most American theaters follow this convention, and again, proper nouns should be respected.

Shubert Theatre, St. Petersburg

Most Broadway theaters, including the St. James Theatre, are written as Theatre.

However, you need to be careful because there are cases where it is not written as -re.

For example, the Lincoln Center Theater in Uptown Manhattan and the Public Theater in Downtown are examples of this. (There is one thing I have to be very picky about with the New York Times: they stubbornly refer to all theaters, whether they are theaters or theaters, regardless of whether they are American or British, as theaters, to suit their taste.)

The persistent practice of even referring to the 'National Theatre in London' as 'National Theatre' is absurd in many ways.

(Isn't it like changing the name arbitrarily?)

Plays are performed in theaters and movies are screened in theaters (yes, that's right).

There are some Americans who steadfastly defend the word "theater" by insisting that theater buildings are written as "theater" and performing arts are written as "theatre" (in the US, it is not called "cinema"), and whenever they do, I respond like this.

I guess you think using -re will make it sound more sophisticated, but can you stop now?

--- pp.

114~115

Long ago, before the advent of the Internet, before all knowledge was available in the blink of an eye, I proofread a novel set in the early 1960s.

I saw a passage that mentioned Burger King and left a note in the margin: 'To the author: Please confirm that there was a Burger King in the 1960s.'

So the author reluctantly came up with a new name, something like Grilled Sandwich Shack. He later confessed that although it is true that he had thoroughly researched the history of Burger King and that there was a Burger King in the 1960s, he changed the name because everyone who had read the manuscript before him had asked the same question, and he thought there was no need to make a fuss over something trivial.

--- p.

147

In general, writers rely more heavily on pronouns than I recommend.

The pronoun proofreading tip boils down to this: "Remember that writing is not speaking."

In spoken language, you can convey your intentions properly even if you use ambiguous pronouns like he and she, but in writing, if there are too many pronouns, it can easily cause confusion.

I strongly advise against referring to two people with the same pronoun within the same sentence.

No, to be blunt, that shouldn't happen in a single paragraph, let alone a single sentence (some queer romance writers I know struggle with this issue, often to the point of tears).

Of course, referring to characters by name can be an alternative.

At first glance, the author might think that mentioning the name Constance three times in seven sentences is excessive.

But from a proofreader's perspective, I think it's better than having readers confused about who the pronoun she refers to.

Personally, I believe that not overusing pronouns is the foundation of writing style, and this foundation should be kept as unnoticed as possible by the reader.

If a paragraph is overflowing with names and pronouns and you feel it's a bit excessive, try changing your stance and rewriting the sentence to remove at least one of them.

It's a tricky task, but it's worth it because it leaves your writing clean, crisp, and powerful.

--- pp.

147~148

∞ When I think of an adjective that is so accurate, original, and perfect that it gives me goosebumps, I sometimes get so satisfied that I unconsciously repeat it over and over again.

For example, if the adjective benighted was used in the description on page 27, it would be used once more on page 31.

If you use a word full of pretense once, make a separate list in your notebook and make sure it doesn't appear twice on a single page of your manuscript.

∞ Be careful not to repeat common nouns/verbs/adjectives/adverbs that don't stand out too much.

Unless it was intentional, it's best not to repeat it in close proximity.

--- p.

149

∞ Writers are overly attached to And then, but in most cases it's perfectly fine to just use then or even omit it altogether.

∞ Writers also use the word suddenly excessively.

∞ He began to cry. is the same as He cried.

Get rid of all the "began to".

∞ This is the sentence that is like a nightmare to me.

And then suddenly he began to cry.

--- p.

154

Italicizing conversational sentences is useful, but should only be done occasionally.

First of all, readers do not like being explicitly told to read in one way or another.

Italics are not always necessary to emphasize dialogue.

Because even a slight change to the sentence can have a sufficient effect of emphasis.

One way is to put the point you want to emphasize in the middle of a conversation and move it to the end of the sentence rather than mixing it with other words.

Once, while proofreading a novel by a great master that was hundreds of pages long, I carefully applied italics about a dozen times.

My intention was to make my point clear, but the author politely declined every time (she was right.

The authors are largely right.

One of the pitfalls of proofreading excellent writing is that you unconsciously make useless suggestions out of a feeling that you need to earn your keep.

--- p.

157

The story begins like this.

“If the author has his own notation rules, try not to touch them.”

I was so captivated by Gibbs's proverb that I typed it up, printed it out large, and stuck it on my office door.

And that too towards the hallway.

Come to think of it, it was 1995. Although my youth was fading, I was a rookie proofreader and production editor who had just joined Random House, drunk on childish arrogance and deluded myself into thinking I could read.

And somehow, I often misread Gibbs's double-edged sword as a right to correct rather than a respectful injunction not to tamper with it, and I forced the rules I had learned, learned, and honed upon writers who had not been blessed with my knowledge and expertise.

How much did the writers hate me?

(syncopation)

The author continued:

“I will fully admit that the proofreader is right and I am wrong, that it is so glaring that I cannot bear to look at it, and that it is absolutely unacceptable. So, will you allow me to leave it as is simply because it is the author’s preferred method?”

What should I say in this situation?

He is an author and a very charming person.

As countless writers who have influenced me have discovered over the years, I am a person who easily gives in to charm offensive tactics.

Above all, I know very well who the lead role is and who the supporting role is.

“Of course,” I said with a smile.

For that reason, 『Straight Man』 was published without any revisions as the author intended, and I don't remember a single review criticizing the problematic notation.

I returned to my original duty of trying my best to prevent that problematic notation from appearing in the book again, because I genuinely thought it was outrageous, both then and now. --- p.

Pages 161-164

Reading out loud can help you see which strengths stand out and which weaknesses are revealed.

This is a universal tip for all writing, but I think it's especially effective in the field of fiction, whether you're a writer or a proofreader.

I wholeheartedly recommend this method.

--- p.

167

grisly/grisly/grizzly/grizzled

Gory crime: A bloody crime is used in conjunction with grisly (violent incidents, etc.) and gruesome.

Tough meat is used in conjunction with gristly meat and meat with many tendons.

Some bears are called grizzly bears (found in North America and Russia).

The mistranslation "grizzly crime" (which would be fine if the crime was actually committed by a bear) is a common and always humorous mistake, but one that should be avoided at all costs.

--- p.

250

sensual/sensuous

Sensual has to do with physical sensations, and sensuous has to do with aesthetics.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, sensuous is a word coined by John Milton in the mid-17th century to express aesthetic satisfaction that, unlike sensual, has no sexual connotations.

Unfortunately, no one, then or now, knows how to distinguish between the two, and the publication of the racy 1969 self-help bestseller The Sensuous Woman—which, according to Milton's principles, should have been called The Sensual Woman—seems to have permanently buried this distinction.

--- pp.

273~274

No rational person would be so foolish as to type out names like Zbigniew Brzezinski, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, or Shohreh Aghdashloo without even checking the spelling.

However, even proper nouns that seem simpler than this are often misspelled not only in the manuscript but also in the final printed version if the proofreader and proofreader are not very careful.

To avoid repeating typos that almost went unnoticed and typographical errors that have led to at least one printing accident, I've been compiling a list of them over the years, and I'm sharing them here in this chapter with a sense of confession.

In fact, I feel a great emotional attachment to this list, as it is the background for the birth of the book you are reading.

And I hope this list will continue to grow.

We could end this chapter here by saying, "If a word begins with a capital letter, always look it up in the dictionary," but where would the fun be in that?

--- pp.

280~281

Pieter Bruegel the Elder

A 16th-century Flemish painter who is often referred to as the Matthew McConaughey of his time because no one can remember the spelling correctly.

It seems likely that this is the case because the surname is written in two ways: Brueghel and Breughel.

His eldest son was also named Pieter, but he seems to have been confused about the family name, as he is often called Pieter Brueghel the Younger.

Fortunately for you, whatever spelling you use, you have something to say.

--- p.

283

Although it is permissible to change the capitalization of a brand name to lowercase, it is not advisable to use the brand name as a verb.

That's why proofreaders have tried (and failed) to stop writers from using the name of the Xerox copier as a verb, meaning "to copy."

But it's no longer possible to argue that searching on Google sites shouldn't be called "googling."

If you must use a brand name as a verb—which I'm not saying is a bad practice, so it's okay—I recommend lowercaseing it.

--- p.

317

equally as, equally as ~

Subtract one from as or equally.

The lyrics of "My Fair Lady" written by Alan Jay Lerner include, "I'd be equally as willing for a dentist to be drilling/than to ever let a woman in my life." This line is often criticized by music enthusiasts as one of the greatest grammatical errors in musical theater lyrics.

Equally as is an eyesore, but than, which should have been replaced with as, is also a target of criticism.

The fact that the character who sings this song in the play is the fastidious grammarian Henry Higgins only adds to the irony.

--- p.

330

Einstein is just one of many great people from whom we can draw inspiration for proverbs.

If it's a famous quote but there's no public source, it's probably said by Abraham Lincoln.

The same goes for Mark Twain, Oscar Wilde (who has thousands of quotes, why even bother attributing them to him), Winston Churchill, and Dorothy Parker (who was almost as prolific as Wilde). (And then there are, in no particular order, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, Voltaire, Mahatma Gandhi, and William Shakespeare (who we so presumptuously and absurdly use, oblivious to how easily every word he ever wrote can be searched.)

--- p.

346

Lazy writers, especially those in business and self-help, often sprinkle their manuscripts with quotes they've culled from the books of equally lazy business/self-help writers and the internet, claiming they're offering uplifting quotes, but this only serves to add to the frustration.

Random House requires its copyeditors to identify and authenticate all such quotations, or cross-reference them with their sources.

Sometimes it feels like swatting away a swarm of locusts with a flyswatter, but what else can you do?

In an age where lies disguised as truth run rampant—led primarily by professional forgers who don't hesitate to denounce facts unfavorable to them as fabrications—I implore you to stop this kind of behavior that perpetuates fortune cookie-like tricks.

Such dull and boring words are the root cause of the damage to human sensibility, and such imitations without originality are an insult to the history of writing.

Most of the time—almost consistently—I was digging deeper into the author's writing, more carefully and from a more objective perspective.

I eliminated unnecessary words, inserted words here and there in overly dense sentences, rearranged paragraphs to make the argument more solid, and caught the author's overuse of adjectives and adverbs.

It was also the proofreader's job to add comments that the sentences were somewhat awkward (write "To the author: AU: Isn't this awkward?" in the margin) or that the expressions were tired and hackneyed ("To the author: Isn't this a cliché?").

In cases where the same point has already been made countless times or is so obvious that it doesn't need to be made at all, I've sometimes just drawn a red line through the entire sentence and written in the margin—though I thought it was overreaching—"To the author: We all know this."

--- p.

11~12

Let's try to last a week without using the following words.

very rather really quite in fact just so pretty of course surely that said actually

If you can get by without using these expressions, which fall under the category of "useless emphasis and vocal stimuli," on weekdays—I won't tell you not to use them when you speak.

If that were the case, most people, especially the British, would be dumb—by the end of the week, their writing skills would have improved significantly.

Well, fine, feel free to use it.

If every time you try to write a sentence, the pen in your hand won't budge.

But if you've written it, go back and delete it.

Get rid of them all, without leaving a single one behind.

Don't even think about leaving the last one behind, saying it looks cute or pitiful.

If the sentence you delete feels empty, find a more powerful and better expression that will convey what you want to say more effectively.

--- pp.

20~21

As much as I love good rules, I'm also a believer in the mantra that "rules are meant to be broken."

But that's only after you've learned the rules.

Here, I'd like to look at what I consider to be the 'great nonrules of the English language'.

You may have encountered this before.

You probably learned this in school, but erase it from your mind now.

Because it is useless.

(syncopation)

But why call it "unprincipled"? In my view, it's unhelpful, unnecessarily restrictive, irresponsible, and completely useless.

Moreover, most of them are of questionable origin.

It's something that falls from the sky and is passed down, but eventually gains a certain level of trust and becomes fixed.

Despite years of desperate attempts by language experts to dispel them, these fictitious principles persist, enduring with a tenacity more tenacious than Keith Richards and Mick Jagger.

With a life force more tenacious than the combined ages of two elderly people.

One problem is that some of these were likely created with good intentions by so-called language experts, and eradicating them for that reason could be like trying to stop a dog from chasing its own tail.

I intend to deal with these irregularities in a neat and tidy manner.

Readers, you can happily bid farewell, confident that I have done thorough research. (Omitted) I must confess that a large part of my job as a proofreader is to help authors avoid being unfairly or justifiably nagged—and this is painful—by people who claim to know better and send angry emails to publishers.

Therefore, even if the origins are somewhat questionable, it is better to follow principles that are unlikely to cause harm.

Also, I warn you in advance that the nonsense I'll explain below is so utter nonsense that if you break it, some readers and online commenters who like to lecture you will be treated with contempt and treat your writing skills as inferior.

Whether you like it or not, betray these principles as if you were telling me to.

It goes without saying that it will be a lot of fun, and I will not spare my support from behind.

--- pp.

24~26

Are contractions not allowed in formal writing?

If you are a Martian who learned English as a foreign language, there is nothing wrong with following this rule.

However, there is no problem at all with the contractions that people use in everyday life, such as don't, can't, and wouldn't.

In fact, if you don't use abbreviations, your writing will usually feel stiff and unnatural.

However, the abbreviation "I'd've" and "should've" can be excessive only in non-light writing.

Since the apostrophe was created to be used in abbreviations, I hope that both the apostrophe and abbreviations will be used effectively.

And while we're on the topic of should've,

The original correct notation is should have (could have, would have, etc.).

But if you're not on the same level as Flannery O'Connor, Zora Neale Hurston, or William Faulkner, but want to add character to your characters' speech like them―(omitted)―I urge you to actively use should've, could've, would've, etc.

--- pp.

31~32

If it appears to be a question, but you don't actually intend to ask a question, don't hesitate to use a period.

In this case, it is considered a statement that does not require a response.

--- p.

44

One thing to note is that commas are not a panacea, much less consecutive commas.

There is a sentence, supposedly from The Times, which I often reluctantly quote in defense of the serial comma, and which I am now disgusted to read, but which I reluctantly quote again, because it shows so well that it is rather inadequate in defending the serial comma.

Well, I hope this is the last time you see it, even though it's unlikely.

Highlights of his global tour include encounters with Nelson Mandela, an 800-year-old demigod and a dildo collector.

Highlights of his world tour include a meeting with Nelson Mandela, an 800-year-old demigod and dildo collector.

What a coincidence! Some might find it amusing, thinking, "Nelson Mandela, an eight-hundred-year-old demigod, and a sex toy collector?"

--- p.

46

As a serial abuser of parenthetical phrases, I advise you not to overuse them.

Especially if the intention is to provoke forced laughter.

If there are too many useless, shy asides, it will sound like a fancy-dressed actor in a Restoration comedy, walking up to the spotlight, covering his mouth, and whispering directly to the audience.

If you talk to the audience that often, they will miss the point of the play.

--- p.

74

Let's take a quick look at the original text here [sic].

sic is Latin for thus, therefore, and accordingly—traditionally italicized and always enclosed in square brackets—and is used to indicate to the reader that a typographical error or other error in a quoted passage has been corrected to preserve the original text, and that the error is not the fault of the author who quoted it.

When quoting a 17th-century text that is full of archaic expressions, it is a good idea to include a note somewhere in the introduction, perhaps in a note or footnote, that the archaic passage has been copied in its entirety, without alteration.

Then there is no need for [sic] to run wild.

Except for the occasional use of [sic] when there are errors or peculiarities that could cause readers to misread or misunderstand.

Sometimes nonfiction writers secretly correct outdated spellings, typos, irregular capitalization, and odd or missing punctuation by quoting numerous passages from older sources or using unusual notation.

I'm not a huge proponent of this practice—it makes the writing less interesting than it used to be, given its quirky charm—but it's a different story when it comes to nonfiction aimed at a mass audience rather than academic books.

Again, if you intend to do so, please let your readers know in advance.

It's something a writer should do.

Don't ever—never—think of using [sic] to disparage a quote as nonsense.

If the intention is to attack the message of the quote itself, rather than just a spelling error.

I'd like to take this opportunity to poke fun at the original author's judgment, but I think if there's one person whose judgment seems questionable, it's the person quoting that quote.

That kind of writing is similar to a t-shirt that says "I'M WITH STUPID" and it makes you look that much more stupid.

--- pp.

77~78

Conversational language is indicated by quotation marks.

Authors who do not use quotation marks (E.

There are also L. Doctorow, William Gaddis, and Cormac McCarthy (who come to mind immediately), but I'll just say one thing.

To reach this level, you must become a master at freely moving between narrative and dialogue.

--- p.

80

I don't think it's going to offend anyone by italicizing six words in a row, but I'd advise against italicizing more than two sentences.

First of all, italics are tiring on the eyes.

Moreover, if there are several italicized paragraphs in a row, it reminds one of a dream scene, and readers tend to want to skip the dream scene.

--- p.

81

60.

If—and this advice applies only to somewhat lighter writing or conversation—a sentence is questionable in form but not semantically, end it with a period, not a question mark.

That's a good idea, don't you think? has a completely different meaning from That's a horrible idea, isn't it.

61.

Use exclamation marks sparingly.

If you use too many exclamation marks, it feels like you are being pushy and pushy, and you will eventually get tired of it.

Some authors recommend using no more than twelve exclamation points per book, while others insist on using no more than twelve in a lifetime.

62.

However, it is also irresponsible not to use exclamation marks when expressing an intense tone, such as "Your hair is on fire!"

A person whose hair is on fire wouldn't believe that.

"What a lovely day!" Even an exclamation like "What a beautiful day!" can sound sarcastic or create a gloomy atmosphere if it ends with a period instead of an exclamation point.

63.

Unless you're over ten and actively working as a comic book artist, don't end your sentences with two exclamation or question marks.

64

Let's not even mention !? or ?!

Because I will never use it.

--- pp.

96~97

It is not polite to start a sentence with an Arabic numeral.

An absolutely impossible example

1967 dawned clear and bright.

1967 dawned.

It's a little better, but it's not that good either.

Nineteen sixty-seven dawned clear and bright.

A better but tautological example

The year 1967 dawned clear and bright.

A much better way is this

Recast your sentence so it needn't begin with a year.

It shouldn't take you but a moment.

Rewrite the sentence without starting with the year.

It only takes a minute.

--- p.

102

No matter what principle you follow, the important thing when writing numbers is to be accurate.

For example, if the author wrote a sentence like, “Twelve useful rules for college graduates entering the job market,” the proofreader would count them first.

This is because it is common to say that you will list twelve things, but when you actually count them, there are only eleven.

It's easy to overlook, so be careful.

Otherwise, you'll just skip over it without even knowing that it says '67 ways to use punctuation marks' and only lists 66 of them.

I intentionally left out item 38 in chapter 3, did anyone notice?

--- p.

106

The real debate in this regard is theater.

It's been around long enough that most American theaters follow this convention, and again, proper nouns should be respected.

Shubert Theatre, St. Petersburg

Most Broadway theaters, including the St. James Theatre, are written as Theatre.

However, you need to be careful because there are cases where it is not written as -re.

For example, the Lincoln Center Theater in Uptown Manhattan and the Public Theater in Downtown are examples of this. (There is one thing I have to be very picky about with the New York Times: they stubbornly refer to all theaters, whether they are theaters or theaters, regardless of whether they are American or British, as theaters, to suit their taste.)

The persistent practice of even referring to the 'National Theatre in London' as 'National Theatre' is absurd in many ways.

(Isn't it like changing the name arbitrarily?)

Plays are performed in theaters and movies are screened in theaters (yes, that's right).

There are some Americans who steadfastly defend the word "theater" by insisting that theater buildings are written as "theater" and performing arts are written as "theatre" (in the US, it is not called "cinema"), and whenever they do, I respond like this.

I guess you think using -re will make it sound more sophisticated, but can you stop now?

--- pp.

114~115

Long ago, before the advent of the Internet, before all knowledge was available in the blink of an eye, I proofread a novel set in the early 1960s.

I saw a passage that mentioned Burger King and left a note in the margin: 'To the author: Please confirm that there was a Burger King in the 1960s.'

So the author reluctantly came up with a new name, something like Grilled Sandwich Shack. He later confessed that although it is true that he had thoroughly researched the history of Burger King and that there was a Burger King in the 1960s, he changed the name because everyone who had read the manuscript before him had asked the same question, and he thought there was no need to make a fuss over something trivial.

--- p.

147

In general, writers rely more heavily on pronouns than I recommend.

The pronoun proofreading tip boils down to this: "Remember that writing is not speaking."

In spoken language, you can convey your intentions properly even if you use ambiguous pronouns like he and she, but in writing, if there are too many pronouns, it can easily cause confusion.

I strongly advise against referring to two people with the same pronoun within the same sentence.

No, to be blunt, that shouldn't happen in a single paragraph, let alone a single sentence (some queer romance writers I know struggle with this issue, often to the point of tears).

Of course, referring to characters by name can be an alternative.

At first glance, the author might think that mentioning the name Constance three times in seven sentences is excessive.

But from a proofreader's perspective, I think it's better than having readers confused about who the pronoun she refers to.

Personally, I believe that not overusing pronouns is the foundation of writing style, and this foundation should be kept as unnoticed as possible by the reader.

If a paragraph is overflowing with names and pronouns and you feel it's a bit excessive, try changing your stance and rewriting the sentence to remove at least one of them.

It's a tricky task, but it's worth it because it leaves your writing clean, crisp, and powerful.

--- pp.

147~148

∞ When I think of an adjective that is so accurate, original, and perfect that it gives me goosebumps, I sometimes get so satisfied that I unconsciously repeat it over and over again.

For example, if the adjective benighted was used in the description on page 27, it would be used once more on page 31.

If you use a word full of pretense once, make a separate list in your notebook and make sure it doesn't appear twice on a single page of your manuscript.

∞ Be careful not to repeat common nouns/verbs/adjectives/adverbs that don't stand out too much.

Unless it was intentional, it's best not to repeat it in close proximity.

--- p.

149

∞ Writers are overly attached to And then, but in most cases it's perfectly fine to just use then or even omit it altogether.

∞ Writers also use the word suddenly excessively.

∞ He began to cry. is the same as He cried.

Get rid of all the "began to".

∞ This is the sentence that is like a nightmare to me.

And then suddenly he began to cry.

--- p.

154

Italicizing conversational sentences is useful, but should only be done occasionally.

First of all, readers do not like being explicitly told to read in one way or another.

Italics are not always necessary to emphasize dialogue.

Because even a slight change to the sentence can have a sufficient effect of emphasis.

One way is to put the point you want to emphasize in the middle of a conversation and move it to the end of the sentence rather than mixing it with other words.

Once, while proofreading a novel by a great master that was hundreds of pages long, I carefully applied italics about a dozen times.

My intention was to make my point clear, but the author politely declined every time (she was right.

The authors are largely right.

One of the pitfalls of proofreading excellent writing is that you unconsciously make useless suggestions out of a feeling that you need to earn your keep.

--- p.

157

The story begins like this.

“If the author has his own notation rules, try not to touch them.”

I was so captivated by Gibbs's proverb that I typed it up, printed it out large, and stuck it on my office door.

And that too towards the hallway.

Come to think of it, it was 1995. Although my youth was fading, I was a rookie proofreader and production editor who had just joined Random House, drunk on childish arrogance and deluded myself into thinking I could read.

And somehow, I often misread Gibbs's double-edged sword as a right to correct rather than a respectful injunction not to tamper with it, and I forced the rules I had learned, learned, and honed upon writers who had not been blessed with my knowledge and expertise.

How much did the writers hate me?

(syncopation)

The author continued:

“I will fully admit that the proofreader is right and I am wrong, that it is so glaring that I cannot bear to look at it, and that it is absolutely unacceptable. So, will you allow me to leave it as is simply because it is the author’s preferred method?”

What should I say in this situation?

He is an author and a very charming person.

As countless writers who have influenced me have discovered over the years, I am a person who easily gives in to charm offensive tactics.

Above all, I know very well who the lead role is and who the supporting role is.

“Of course,” I said with a smile.

For that reason, 『Straight Man』 was published without any revisions as the author intended, and I don't remember a single review criticizing the problematic notation.

I returned to my original duty of trying my best to prevent that problematic notation from appearing in the book again, because I genuinely thought it was outrageous, both then and now. --- p.

Pages 161-164

Reading out loud can help you see which strengths stand out and which weaknesses are revealed.

This is a universal tip for all writing, but I think it's especially effective in the field of fiction, whether you're a writer or a proofreader.

I wholeheartedly recommend this method.

--- p.

167

grisly/grisly/grizzly/grizzled

Gory crime: A bloody crime is used in conjunction with grisly (violent incidents, etc.) and gruesome.

Tough meat is used in conjunction with gristly meat and meat with many tendons.

Some bears are called grizzly bears (found in North America and Russia).

The mistranslation "grizzly crime" (which would be fine if the crime was actually committed by a bear) is a common and always humorous mistake, but one that should be avoided at all costs.

--- p.

250

sensual/sensuous

Sensual has to do with physical sensations, and sensuous has to do with aesthetics.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, sensuous is a word coined by John Milton in the mid-17th century to express aesthetic satisfaction that, unlike sensual, has no sexual connotations.

Unfortunately, no one, then or now, knows how to distinguish between the two, and the publication of the racy 1969 self-help bestseller The Sensuous Woman—which, according to Milton's principles, should have been called The Sensual Woman—seems to have permanently buried this distinction.

--- pp.

273~274

No rational person would be so foolish as to type out names like Zbigniew Brzezinski, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, or Shohreh Aghdashloo without even checking the spelling.

However, even proper nouns that seem simpler than this are often misspelled not only in the manuscript but also in the final printed version if the proofreader and proofreader are not very careful.

To avoid repeating typos that almost went unnoticed and typographical errors that have led to at least one printing accident, I've been compiling a list of them over the years, and I'm sharing them here in this chapter with a sense of confession.

In fact, I feel a great emotional attachment to this list, as it is the background for the birth of the book you are reading.

And I hope this list will continue to grow.

We could end this chapter here by saying, "If a word begins with a capital letter, always look it up in the dictionary," but where would the fun be in that?

--- pp.

280~281

Pieter Bruegel the Elder

A 16th-century Flemish painter who is often referred to as the Matthew McConaughey of his time because no one can remember the spelling correctly.

It seems likely that this is the case because the surname is written in two ways: Brueghel and Breughel.

His eldest son was also named Pieter, but he seems to have been confused about the family name, as he is often called Pieter Brueghel the Younger.

Fortunately for you, whatever spelling you use, you have something to say.

--- p.

283

Although it is permissible to change the capitalization of a brand name to lowercase, it is not advisable to use the brand name as a verb.

That's why proofreaders have tried (and failed) to stop writers from using the name of the Xerox copier as a verb, meaning "to copy."

But it's no longer possible to argue that searching on Google sites shouldn't be called "googling."

If you must use a brand name as a verb—which I'm not saying is a bad practice, so it's okay—I recommend lowercaseing it.

--- p.

317

equally as, equally as ~

Subtract one from as or equally.

The lyrics of "My Fair Lady" written by Alan Jay Lerner include, "I'd be equally as willing for a dentist to be drilling/than to ever let a woman in my life." This line is often criticized by music enthusiasts as one of the greatest grammatical errors in musical theater lyrics.

Equally as is an eyesore, but than, which should have been replaced with as, is also a target of criticism.

The fact that the character who sings this song in the play is the fastidious grammarian Henry Higgins only adds to the irony.

--- p.

330

Einstein is just one of many great people from whom we can draw inspiration for proverbs.

If it's a famous quote but there's no public source, it's probably said by Abraham Lincoln.

The same goes for Mark Twain, Oscar Wilde (who has thousands of quotes, why even bother attributing them to him), Winston Churchill, and Dorothy Parker (who was almost as prolific as Wilde). (And then there are, in no particular order, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, Voltaire, Mahatma Gandhi, and William Shakespeare (who we so presumptuously and absurdly use, oblivious to how easily every word he ever wrote can be searched.)

--- p.

346

Lazy writers, especially those in business and self-help, often sprinkle their manuscripts with quotes they've culled from the books of equally lazy business/self-help writers and the internet, claiming they're offering uplifting quotes, but this only serves to add to the frustration.

Random House requires its copyeditors to identify and authenticate all such quotations, or cross-reference them with their sources.

Sometimes it feels like swatting away a swarm of locusts with a flyswatter, but what else can you do?

In an age where lies disguised as truth run rampant—led primarily by professional forgers who don't hesitate to denounce facts unfavorable to them as fabrications—I implore you to stop this kind of behavior that perpetuates fortune cookie-like tricks.

Such dull and boring words are the root cause of the damage to human sensibility, and such imitations without originality are an insult to the history of writing.

--- pp.

347~348

347~348

Publisher's Review

From the basic principles of English writing to how to use punctuation,

Grammar errors that ruin sentences and even English words that confuse even writers

All About English Writing

The manuscripts that proofreaders receive are full of words that don't fit the context, typos, misspellings, and inscriptions.

However, when you look at the final printed version, that is, the finished product, you cannot feel any trace of the proofreader who exchanged countless notes with the author, having a kind of conversation “as if competing with colored pens,” repeatedly refining and revising the author’s sentences.

The reader assumes that every word from the first page to the last belongs entirely to the author.

The proofreader's job is accomplished when such an illusion occurs, when it is simply invisible to the reader.

This is because readers can quickly detect awkward and unnatural writing, but have difficulty detecting sophisticated and meticulous writing.

The primary role of a proofreader is to “help authors avoid being unfairly or justifiably scolded—and this is painful—by ‘people who write angry emails to publishers claiming they know better.’”

Therefore, the simple skill of catching grammar and spelling errors, as well as words that the author overuses or misuses, is the foundation of proofreading.

For proofreading to rise beyond a skill to an art, the proofreader must have the ability to “listen to the text” and become the author’s alter ego.

That's why the saying that proofreading is "reading that damned sentence 657 times while trying to figure out how you would have edited, changed, and rewritten it if you were the author" isn't just a joke.

Even famous writers make grammatical errors, misspell things, use punctuation incorrectly, and use words out of context.

When revisions like this occur, proofreaders often engage in heated arguments or 'push-pushy' with the author.

Some writers insist on leaving obvious grammatical errors in, some politely decline italics, and some dismiss a proofreader's suggestions for sentence revisions, scribbling, "You should do that in your own fucking book."

Even proofreaders make ridiculous mistakes.

The author also confesses in this book a list of proper nouns that he has compiled over the years to avoid repeating the mistakes that led to printing accidents by misspelling proper nouns such as people's names, place names, and brand names.

What both writers and proofreaders must know

The Basics of English Writing

However, even established writers consider professional proofreading a safety net and are willing to collaborate with proofreaders.

The author reiterates the fundamental principles of English writing, explaining which rules are nonsense to ignore, which rules should be taken as maxims, and what the minimum principles are that I need to know when polishing my English writing.

In addition, it examines the current state of English usage by examining the phenomenon of consideration for minorities and gender sensitivity being reflected in language, such as the use of the singular pronoun they (referring to a single individual without specifying gender) or the tendency to write candidate for men and female candidate for women, as examples. It also vividly conveys how the specific practices of 'writers' at the center of the production site are driving the evolution and degeneration of language and how the power of writers is realized.

This advice isn't just for established writers and professional proofreaders.

Because, as the author says, we are all potential authors or already 'writers'.

We write something every day.

Write product reviews and school assignments, work announcements and letters, online posts and journal entries.

I use emails on a daily basis and also write professionally.

As someone who has made a living editing other people's writing, I know from experience that everyone wants to write better.

They want their writing to stand out, to convey their message more clearly and polishedly, and to be more persuasive.

To do that, we need to reduce mistakes.

There are already plenty of guidebooks out there to offer direction to those who write, but this book resolutely refuses the fate of a brick book, kept on a bookshelf and rarely read.

In fact, this is probably the first guidebook you'll want to read from beginning to end in one sitting.

Grammar errors that ruin sentences and even English words that confuse even writers

All About English Writing

The manuscripts that proofreaders receive are full of words that don't fit the context, typos, misspellings, and inscriptions.

However, when you look at the final printed version, that is, the finished product, you cannot feel any trace of the proofreader who exchanged countless notes with the author, having a kind of conversation “as if competing with colored pens,” repeatedly refining and revising the author’s sentences.

The reader assumes that every word from the first page to the last belongs entirely to the author.

The proofreader's job is accomplished when such an illusion occurs, when it is simply invisible to the reader.

This is because readers can quickly detect awkward and unnatural writing, but have difficulty detecting sophisticated and meticulous writing.

The primary role of a proofreader is to “help authors avoid being unfairly or justifiably scolded—and this is painful—by ‘people who write angry emails to publishers claiming they know better.’”

Therefore, the simple skill of catching grammar and spelling errors, as well as words that the author overuses or misuses, is the foundation of proofreading.

For proofreading to rise beyond a skill to an art, the proofreader must have the ability to “listen to the text” and become the author’s alter ego.

That's why the saying that proofreading is "reading that damned sentence 657 times while trying to figure out how you would have edited, changed, and rewritten it if you were the author" isn't just a joke.

Even famous writers make grammatical errors, misspell things, use punctuation incorrectly, and use words out of context.

When revisions like this occur, proofreaders often engage in heated arguments or 'push-pushy' with the author.

Some writers insist on leaving obvious grammatical errors in, some politely decline italics, and some dismiss a proofreader's suggestions for sentence revisions, scribbling, "You should do that in your own fucking book."

Even proofreaders make ridiculous mistakes.

The author also confesses in this book a list of proper nouns that he has compiled over the years to avoid repeating the mistakes that led to printing accidents by misspelling proper nouns such as people's names, place names, and brand names.

What both writers and proofreaders must know

The Basics of English Writing

However, even established writers consider professional proofreading a safety net and are willing to collaborate with proofreaders.

The author reiterates the fundamental principles of English writing, explaining which rules are nonsense to ignore, which rules should be taken as maxims, and what the minimum principles are that I need to know when polishing my English writing.

In addition, it examines the current state of English usage by examining the phenomenon of consideration for minorities and gender sensitivity being reflected in language, such as the use of the singular pronoun they (referring to a single individual without specifying gender) or the tendency to write candidate for men and female candidate for women, as examples. It also vividly conveys how the specific practices of 'writers' at the center of the production site are driving the evolution and degeneration of language and how the power of writers is realized.

This advice isn't just for established writers and professional proofreaders.

Because, as the author says, we are all potential authors or already 'writers'.

We write something every day.

Write product reviews and school assignments, work announcements and letters, online posts and journal entries.

I use emails on a daily basis and also write professionally.

As someone who has made a living editing other people's writing, I know from experience that everyone wants to write better.

They want their writing to stand out, to convey their message more clearly and polishedly, and to be more persuasive.

To do that, we need to reduce mistakes.

There are already plenty of guidebooks out there to offer direction to those who write, but this book resolutely refuses the fate of a brick book, kept on a bookshelf and rarely read.

In fact, this is probably the first guidebook you'll want to read from beginning to end in one sitting.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Publication date: February 21, 2022

- Page count, weight, size: 360 pages | 640g | 152*223*22mm

- ISBN13: 9791157687794

- ISBN10: 1157687792

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)