Noise: The noise of thoughts

|

Description

Book Introduction

Daniel Kahneman's new book, "Thinking, Fast and Slow," is out after 10 years. “The most important book I’ve read in the last ten years. “It’s a true masterpiece.” Angela Duckworth, author of Grit Where there is judgment, there is noise! Why does the "noise" that leads to bad decisions occur? How can we reduce it? An expanded version of the wisdom of behavioral economics that follows "Thinking, Fast and Slow" Three world-renowned scholars unravel the flaws in human judgment and their solutions. What if the same judge, doctor, or interviewer makes completely different decisions in the morning and afternoon, on Monday and Wednesday? If decisions that should be the same aren't, then there's noise. Noise is everywhere, but no one is aware of its presence. So the noise is left unchecked and we repeat bad choices. Why are our judgments so susceptible to noise? How can we avoid it and make good decisions? This is the first study to identify the noise in our thinking, brought together by three world-renowned scholars: Daniel Kahneman, the founder of behavioral economics and Nobel Prize winner; Olivier Sibony, a global authority on strategic decision-making; and Cass Sunstein, a world-renowned policy expert and distinguished legal scholar. A noise-busting report that guides individuals and organizations to make better choices. |

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Preface Two Errors

Part 1: Finding Noise

Chapter 1: Noise and the Criminal Justice System | Chapter 2: Institutional Noise | Chapter 3: One-Time Decisions

Part 2: Noise and the Human Mind

Chapter 4: The Problem of Judgment | Chapter 5: Measuring Error | Chapter 6: Analyzing Noise | Chapter 7: Contextual Noise | Chapter 8: How Groups Amplify Noise

Part 3: Noise in Predictive Judgments

Chapter 9: Judgments and Models | Chapter 10: Noiseless Rules | Chapter 11: Objective Ignorance | Chapter 12: The Valley of the Summit

Part 4: How Does Noise Occur?

Chapter 13: Guesswork, Bias, and Noise | Chapter 14: Matching Processes | Chapter 15: Scaling | Chapter 16: Patterns | Chapter 17: Sources of Noise

Part 5: Judgment Improvement

Chapter 18: Good Judges Make Good Decisions | Chapter 19: Debiasing and Decision Hygiene | Chapter 20: Forensic Science and the Sequential Presentation of Information | Chapter 21: Selecting and Aggregating Predictions | Chapter 22: Medical Guidelines | Chapter 23: Performance Evaluation Scales | Chapter 24: Structuring Recruitment Systems | Chapter 25: Intermediate Evaluation Protocols

Part 6 Optimal Noise

Chapter 26: The Cost of Noise Reduction | Chapter 27: Dignity | Chapter 28: Rules or Standards?

Let's seriously consider the conclusion noise.

Epilogue: A World with Reduced Noise

Appendix A: How to Conduct a Noise Audit

Appendix B Checklist for Decision Observers

Appendix C: Prediction Revisions

main

Acknowledgements

Search

Part 1: Finding Noise

Chapter 1: Noise and the Criminal Justice System | Chapter 2: Institutional Noise | Chapter 3: One-Time Decisions

Part 2: Noise and the Human Mind

Chapter 4: The Problem of Judgment | Chapter 5: Measuring Error | Chapter 6: Analyzing Noise | Chapter 7: Contextual Noise | Chapter 8: How Groups Amplify Noise

Part 3: Noise in Predictive Judgments

Chapter 9: Judgments and Models | Chapter 10: Noiseless Rules | Chapter 11: Objective Ignorance | Chapter 12: The Valley of the Summit

Part 4: How Does Noise Occur?

Chapter 13: Guesswork, Bias, and Noise | Chapter 14: Matching Processes | Chapter 15: Scaling | Chapter 16: Patterns | Chapter 17: Sources of Noise

Part 5: Judgment Improvement

Chapter 18: Good Judges Make Good Decisions | Chapter 19: Debiasing and Decision Hygiene | Chapter 20: Forensic Science and the Sequential Presentation of Information | Chapter 21: Selecting and Aggregating Predictions | Chapter 22: Medical Guidelines | Chapter 23: Performance Evaluation Scales | Chapter 24: Structuring Recruitment Systems | Chapter 25: Intermediate Evaluation Protocols

Part 6 Optimal Noise

Chapter 26: The Cost of Noise Reduction | Chapter 27: Dignity | Chapter 28: Rules or Standards?

Let's seriously consider the conclusion noise.

Epilogue: A World with Reduced Noise

Appendix A: How to Conduct a Noise Audit

Appendix B Checklist for Decision Observers

Appendix C: Prediction Revisions

main

Acknowledgements

Search

Detailed image

Into the book

To understand the errors that occur in judgment, we need to understand both bias and noise.

As you'll soon discover, sometimes noise can be a more serious problem.

But globally, noise rarely figures prominently in public discussions about human error or in internal discussions within many organizations.

If bias is the star of the show, noise is the supporting actor, usually unnoticed by the audience.

Bias is a central topic in thousands of scientific articles and dozens of popular books, but noise is rarely mentioned in these literature.

This book seeks to correct this imbalance between bias and noise.

--- From the "Preface"

A study of thousands of juvenile court decisions found that after a local football team lost a weekend game, judges handed down harsher sentences the following Monday (and, to a lesser extent, throughout the rest of the week).

Black defendants also receive disproportionately harsh sentences.

Another study of 1.5 million judicial decisions over the past 30 years yielded similar results.

Judges were found to be more harsh in sentencing local football teams the day after they lost a game than the day after they won.

--- 「1.

From “Noise and the Criminal Justice System”

Even when injustice is the only concern, institutional noise creates other problems.

People who are influenced by evaluative judgments believe that the values represented by the judgment are those of the system, not of the individual who made the judgment.

If some customers who complain about defective laptops get full refunds while others only get an apology, something must be seriously wrong.

Or, if an employee who has been with the company for five years requests a promotion, but another employee with the same job performance politely declines the promotion request, something is seriously wrong here too.

Institutional noise is inconsistency.

Inconsistency undermines the credibility of the system.

--- 「4.

From “The Problem of Judgment”

The invisibility of noise is a direct result of causal thinking.

Noise is inherently statistical.

It is only when we think statistically about a collection of similar judgments that the noise becomes noticeable.

Once you do that, it's not easy to get past the noise.

For example, noise is the variability of retrospective statistics observed in sentencing and insurance premium calculations.

Noise is also the range of possible outcomes when we consider how to predict future outcomes.

It is a scattering of bullet marks on the target.

From a causal perspective, noise does not exist anywhere.

But from a statistical standpoint, noise is everywhere.

--- 「17.

From “The Source of Noise”

When an interview isn't the only source of information about a candidate—for example, when other data such as test scores and reference materials are also available—these diverse inputs must be synthesized to form an overall judgment.

Here, the question may arise: 'Should we synthesize the input using judgment (clinical aggregation) or a formula (mechanical aggregation)?'

As we saw in Chapter 9, mechanistic approaches are superior to clinical approaches in general and in specific cases such as predicting work performance.

Unfortunately, research shows that the vast majority of HR professionals prefer clinical aggregation.

This practice adds another source of noise to an already noisy personnel process.

--- 「24.

From “Structuring the Recruitment System”

These cases lead to an inevitable conclusion.

In an uncertain world, predictive algorithms cannot be perfect, but they can make decisions that are far less imperfect than noisy and often biased human judgments.

Algorithms can also outperform humans in terms of validity (a good algorithm almost always makes better predictions) and discriminability (a good algorithm can make less biased judgments than a human judge).

If algorithms make fewer mistakes than human experts, yet we tend to intuitively prefer human judgments of things, then that tendency should be carefully examined.

As you'll soon discover, sometimes noise can be a more serious problem.

But globally, noise rarely figures prominently in public discussions about human error or in internal discussions within many organizations.

If bias is the star of the show, noise is the supporting actor, usually unnoticed by the audience.

Bias is a central topic in thousands of scientific articles and dozens of popular books, but noise is rarely mentioned in these literature.

This book seeks to correct this imbalance between bias and noise.

--- From the "Preface"

A study of thousands of juvenile court decisions found that after a local football team lost a weekend game, judges handed down harsher sentences the following Monday (and, to a lesser extent, throughout the rest of the week).

Black defendants also receive disproportionately harsh sentences.

Another study of 1.5 million judicial decisions over the past 30 years yielded similar results.

Judges were found to be more harsh in sentencing local football teams the day after they lost a game than the day after they won.

--- 「1.

From “Noise and the Criminal Justice System”

Even when injustice is the only concern, institutional noise creates other problems.

People who are influenced by evaluative judgments believe that the values represented by the judgment are those of the system, not of the individual who made the judgment.

If some customers who complain about defective laptops get full refunds while others only get an apology, something must be seriously wrong.

Or, if an employee who has been with the company for five years requests a promotion, but another employee with the same job performance politely declines the promotion request, something is seriously wrong here too.

Institutional noise is inconsistency.

Inconsistency undermines the credibility of the system.

--- 「4.

From “The Problem of Judgment”

The invisibility of noise is a direct result of causal thinking.

Noise is inherently statistical.

It is only when we think statistically about a collection of similar judgments that the noise becomes noticeable.

Once you do that, it's not easy to get past the noise.

For example, noise is the variability of retrospective statistics observed in sentencing and insurance premium calculations.

Noise is also the range of possible outcomes when we consider how to predict future outcomes.

It is a scattering of bullet marks on the target.

From a causal perspective, noise does not exist anywhere.

But from a statistical standpoint, noise is everywhere.

--- 「17.

From “The Source of Noise”

When an interview isn't the only source of information about a candidate—for example, when other data such as test scores and reference materials are also available—these diverse inputs must be synthesized to form an overall judgment.

Here, the question may arise: 'Should we synthesize the input using judgment (clinical aggregation) or a formula (mechanical aggregation)?'

As we saw in Chapter 9, mechanistic approaches are superior to clinical approaches in general and in specific cases such as predicting work performance.

Unfortunately, research shows that the vast majority of HR professionals prefer clinical aggregation.

This practice adds another source of noise to an already noisy personnel process.

--- 「24.

From “Structuring the Recruitment System”

These cases lead to an inevitable conclusion.

In an uncertain world, predictive algorithms cannot be perfect, but they can make decisions that are far less imperfect than noisy and often biased human judgments.

Algorithms can also outperform humans in terms of validity (a good algorithm almost always makes better predictions) and discriminability (a good algorithm can make less biased judgments than a human judge).

If algorithms make fewer mistakes than human experts, yet we tend to intuitively prefer human judgments of things, then that tendency should be carefully examined.

--- 「26.

From “Noise Reduction Cost”

From “Noise Reduction Cost”

Publisher's Review

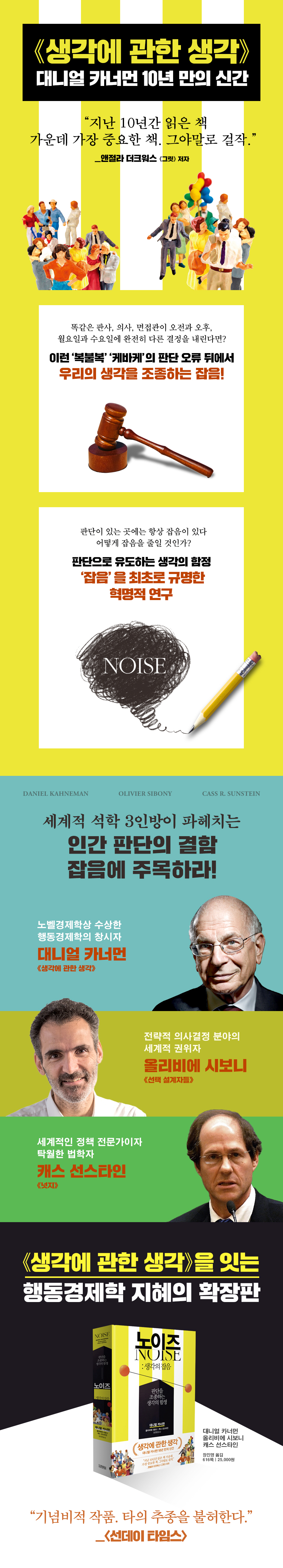

Daniel Kahneman, 'Thinking, Fast and Slow: An Expanded and Deepened Edition'

Opening the Future of Cognitive Psychology and Behavioral Economics

Daniel Kahneman, the 'founder of behavioral economics,' returns with another brilliant insight into human psychology in Noise: A Flaw in Human Judgment.

This new book, released after 10 years, expands and deepens the discussion of "Thinking, Fast and Slow."

This revolutionary research report, the first to identify "noise," another source of judgmental error alongside bias, uncovers the noise hidden in a wide range of cases across fields such as criminal justice, healthcare, business forecasting, performance evaluations, fingerprinting, and politics.

This was possible because three world-renowned scholars, including a cognitive psychologist (Daniel Kahneman) who won the Nobel Prize in Economics, a top management strategist in the field of decision-making (Olivier Sibony), and a policy expert and legal scholar (Cass Sunstein), joined forces.

With the publication of this book, the classics of cognitive psychology and behavioral economics now number three.

If "Thinking, Fast and Slow" was a pioneer in broadening the horizons of human understanding by explaining the human thought system with simple, clear, and insightful ideas, "Nudge" followed that insight and proposed a choice architecture technique that leads to smart choices.

And "Noise: The Noise of Thought" revealed the causes of judgment errors that we didn't even know existed, suggesting a new path for cognitive psychology and behavioral economics.

The invisible noise finally revealed itself.

It's time to confront the noise of thought with three world-renowned scholars.

Noise occurs when judgments that should be the same are not.

: Definition of noise

This book categorizes the errors we make into two types.

It's bias and noise.

Bias is a judgment that 'systematically deviates' from the core of the problem.

If a job applicant's appearance leaves a positive impression on many interviewers even though it is unrelated to the job they are applying for, they are likely to benefit from a bias called the "halo effect."

The applicant's appearance diverted the interviewers' focus from the core of the job.

Noise is a judgment that is 'randomly distributed' around the core of the problem.

If two interviewers are asked to rate the performance of the same two candidates, there is a 25 percent chance that they will disagree.

Even if an applicant is given a passing grade, the scores will vary from interviewer to interviewer.

Interviewers react differently to the same applicant and reach different conclusions.

This is not very desirable.

The greater the difference in judgment, the slower or more difficult it is to reach a consensus.

Noise is unwanted variability that appears in judgments.

Can we really trust the experts?

: Case of noise

Two men have been indicted for similar embezzlement cases.

However, one person was sentenced to 20 years in prison, and the other was sentenced to 117 days in prison.

How could this happen? Even if the sentences differ depending on the judge, isn't the disparity so severe that it's unacceptable?

Two insurance underwriters working for the same insurance company were asked to review the same case and calculate their own insurance premiums.

The company's executives estimated that the difference between the two premiums would be 10 percent (if A were $9,500, B would be $15,000).

But the actual difference was 55 percent.

This means that when A calculates the insurance premium at $9,500, B calculates it at $16,700.

Whether the premium is too low or too high, it is a loss for the insurance company.

The author calls the undesirable variability observed in organizations that employ interchangeable experts, such as sentencing judges and insurance underwriters, “system noise.”

It's clear why institutional noise is a problem.

Because inconsistent systems lead to a loss of trust.

The author criticizes the expert's judgment, which ends up being 'lucky or not' or 'likely a guess', as being similar to a 'lottery' or 'drawing lots'.

And it also tells us the shocking fact that this 'lottery' happens twice.

For example, the results can vary depending on which doctor you consult.

This is the first draw where the key question is 'who will get caught', just like the judge and insurance examiner cases mentioned above.

At this time, 'human noise' occurs.

The second draw takes place next.

The moment the doctor you meet in the examination room makes a decision, the outcome will vary depending on his situation.

Physicians are more likely to prescribe narcotic painkillers in the late afternoon, when patients feel stressed and tired, than earlier in the day, a new study finds.

This is 'human noise'.

If bias is the main character, noise is the supporting actor.

: Characteristics of noise

So why are we so vulnerable to noise? Because we can't see it.

So it is left unattended.

The bias is clearly visible.

So diagnosis and prescription are possible.

Comparisons of noise and bias appear throughout the book.

In particular, the observation that “if bias is the star of the show, noise is usually a supporting actor who is not easily noticed by the audience” (p. 13) clearly shows the characteristics of bias and noise.

Humans understand the world causally.

We try to digest and understand the cause and effect of an incident by creating a story.

If this story ends in error, the problem lies with the bias of the protagonist.

As such, bias is easily detected when explaining why a decision was wrong.

The psychological bias that leads people to underestimate the time a project will take is called the planning fallacy.

Next time, don't do that.

On the other hand, noise, which is a supporting actor, is not easily found in the causal world.

But from a statistical perspective, we see noise.

The author even says that where there is judgment, there is always noise.

Statistical thinking begins with not trusting your intuition.

There's no reason to believe that a CEO will be reappointed two years from now just because he or she fits my definition of a successful entrepreneur.

The CEO tenure rates of companies are already statistically known, and these figures are completely separate from my intuition or favorability.

In times like these, it would be better to trust statistics.

The only way to reduce invisible noise is through prevention.

: Noise reduction

The author likens removing easily identifiable biases to direct treatment, while reducing noise that is difficult to identify is like preventative hygiene.

Noise can only be prevented before it occurs.

The six principles presented as a noise reduction strategy are as follows:

(1) The goal of judgment is not the expression of individuality, but accuracy.

Individuality is a source of noise between people and should be avoided.

Therefore, the algorithm is recommended.

It's not because the algorithm has insight.

The strength of the algorithm is its ‘noiselessness’.

(2) Statistical thinking.

Causal thinking, leveraging personal experience, cuts through the noise.

Noise can be avoided by using external sources and perspectives.

(3) Structure judgment as an independent task.

Dividing multiple evaluation items into independent evaluations can limit the psychological mechanism that seeks consistency.

It is important to remember that when witnesses to an incident talk to each other, their testimony can become contaminated.

(4) Resist early intuition.

Look at the statistics and data first, then allow your intuition to guide your decision-making process.

Intuition must emerge at the last moment to overcome the noise.

(5) Aggregate multiple independent judgments.

Because people influence each other, it is important to gather each person's judgment before discussing.

This way, opinions won't be biased towards one side and noise will be reduced.

(6) Relative judgment and relative scale.

Relative judgments are less noisy than absolute judgments.

Because ranking items in a list rather than rating each value individually improves the quality of judgment.

Opening the Future of Cognitive Psychology and Behavioral Economics

Daniel Kahneman, the 'founder of behavioral economics,' returns with another brilliant insight into human psychology in Noise: A Flaw in Human Judgment.

This new book, released after 10 years, expands and deepens the discussion of "Thinking, Fast and Slow."

This revolutionary research report, the first to identify "noise," another source of judgmental error alongside bias, uncovers the noise hidden in a wide range of cases across fields such as criminal justice, healthcare, business forecasting, performance evaluations, fingerprinting, and politics.

This was possible because three world-renowned scholars, including a cognitive psychologist (Daniel Kahneman) who won the Nobel Prize in Economics, a top management strategist in the field of decision-making (Olivier Sibony), and a policy expert and legal scholar (Cass Sunstein), joined forces.

With the publication of this book, the classics of cognitive psychology and behavioral economics now number three.

If "Thinking, Fast and Slow" was a pioneer in broadening the horizons of human understanding by explaining the human thought system with simple, clear, and insightful ideas, "Nudge" followed that insight and proposed a choice architecture technique that leads to smart choices.

And "Noise: The Noise of Thought" revealed the causes of judgment errors that we didn't even know existed, suggesting a new path for cognitive psychology and behavioral economics.

The invisible noise finally revealed itself.

It's time to confront the noise of thought with three world-renowned scholars.

Noise occurs when judgments that should be the same are not.

: Definition of noise

This book categorizes the errors we make into two types.

It's bias and noise.

Bias is a judgment that 'systematically deviates' from the core of the problem.

If a job applicant's appearance leaves a positive impression on many interviewers even though it is unrelated to the job they are applying for, they are likely to benefit from a bias called the "halo effect."

The applicant's appearance diverted the interviewers' focus from the core of the job.

Noise is a judgment that is 'randomly distributed' around the core of the problem.

If two interviewers are asked to rate the performance of the same two candidates, there is a 25 percent chance that they will disagree.

Even if an applicant is given a passing grade, the scores will vary from interviewer to interviewer.

Interviewers react differently to the same applicant and reach different conclusions.

This is not very desirable.

The greater the difference in judgment, the slower or more difficult it is to reach a consensus.

Noise is unwanted variability that appears in judgments.

Can we really trust the experts?

: Case of noise

Two men have been indicted for similar embezzlement cases.

However, one person was sentenced to 20 years in prison, and the other was sentenced to 117 days in prison.

How could this happen? Even if the sentences differ depending on the judge, isn't the disparity so severe that it's unacceptable?

Two insurance underwriters working for the same insurance company were asked to review the same case and calculate their own insurance premiums.

The company's executives estimated that the difference between the two premiums would be 10 percent (if A were $9,500, B would be $15,000).

But the actual difference was 55 percent.

This means that when A calculates the insurance premium at $9,500, B calculates it at $16,700.

Whether the premium is too low or too high, it is a loss for the insurance company.

The author calls the undesirable variability observed in organizations that employ interchangeable experts, such as sentencing judges and insurance underwriters, “system noise.”

It's clear why institutional noise is a problem.

Because inconsistent systems lead to a loss of trust.

The author criticizes the expert's judgment, which ends up being 'lucky or not' or 'likely a guess', as being similar to a 'lottery' or 'drawing lots'.

And it also tells us the shocking fact that this 'lottery' happens twice.

For example, the results can vary depending on which doctor you consult.

This is the first draw where the key question is 'who will get caught', just like the judge and insurance examiner cases mentioned above.

At this time, 'human noise' occurs.

The second draw takes place next.

The moment the doctor you meet in the examination room makes a decision, the outcome will vary depending on his situation.

Physicians are more likely to prescribe narcotic painkillers in the late afternoon, when patients feel stressed and tired, than earlier in the day, a new study finds.

This is 'human noise'.

If bias is the main character, noise is the supporting actor.

: Characteristics of noise

So why are we so vulnerable to noise? Because we can't see it.

So it is left unattended.

The bias is clearly visible.

So diagnosis and prescription are possible.

Comparisons of noise and bias appear throughout the book.

In particular, the observation that “if bias is the star of the show, noise is usually a supporting actor who is not easily noticed by the audience” (p. 13) clearly shows the characteristics of bias and noise.

Humans understand the world causally.

We try to digest and understand the cause and effect of an incident by creating a story.

If this story ends in error, the problem lies with the bias of the protagonist.

As such, bias is easily detected when explaining why a decision was wrong.

The psychological bias that leads people to underestimate the time a project will take is called the planning fallacy.

Next time, don't do that.

On the other hand, noise, which is a supporting actor, is not easily found in the causal world.

But from a statistical perspective, we see noise.

The author even says that where there is judgment, there is always noise.

Statistical thinking begins with not trusting your intuition.

There's no reason to believe that a CEO will be reappointed two years from now just because he or she fits my definition of a successful entrepreneur.

The CEO tenure rates of companies are already statistically known, and these figures are completely separate from my intuition or favorability.

In times like these, it would be better to trust statistics.

The only way to reduce invisible noise is through prevention.

: Noise reduction

The author likens removing easily identifiable biases to direct treatment, while reducing noise that is difficult to identify is like preventative hygiene.

Noise can only be prevented before it occurs.

The six principles presented as a noise reduction strategy are as follows:

(1) The goal of judgment is not the expression of individuality, but accuracy.

Individuality is a source of noise between people and should be avoided.

Therefore, the algorithm is recommended.

It's not because the algorithm has insight.

The strength of the algorithm is its ‘noiselessness’.

(2) Statistical thinking.

Causal thinking, leveraging personal experience, cuts through the noise.

Noise can be avoided by using external sources and perspectives.

(3) Structure judgment as an independent task.

Dividing multiple evaluation items into independent evaluations can limit the psychological mechanism that seeks consistency.

It is important to remember that when witnesses to an incident talk to each other, their testimony can become contaminated.

(4) Resist early intuition.

Look at the statistics and data first, then allow your intuition to guide your decision-making process.

Intuition must emerge at the last moment to overcome the noise.

(5) Aggregate multiple independent judgments.

Because people influence each other, it is important to gather each person's judgment before discussing.

This way, opinions won't be biased towards one side and noise will be reduced.

(6) Relative judgment and relative scale.

Relative judgments are less noisy than absolute judgments.

Because ranking items in a list rather than rating each value individually improves the quality of judgment.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Publication date: April 29, 2022

- Format: Hardcover book binding method guide

- Page count, weight, size: 616 pages | 998g | 152*225*35mm

- ISBN13: 9788934961567

- ISBN10: 8934961562

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)