Each season

|

Description

Book Introduction

- A word from MD

-

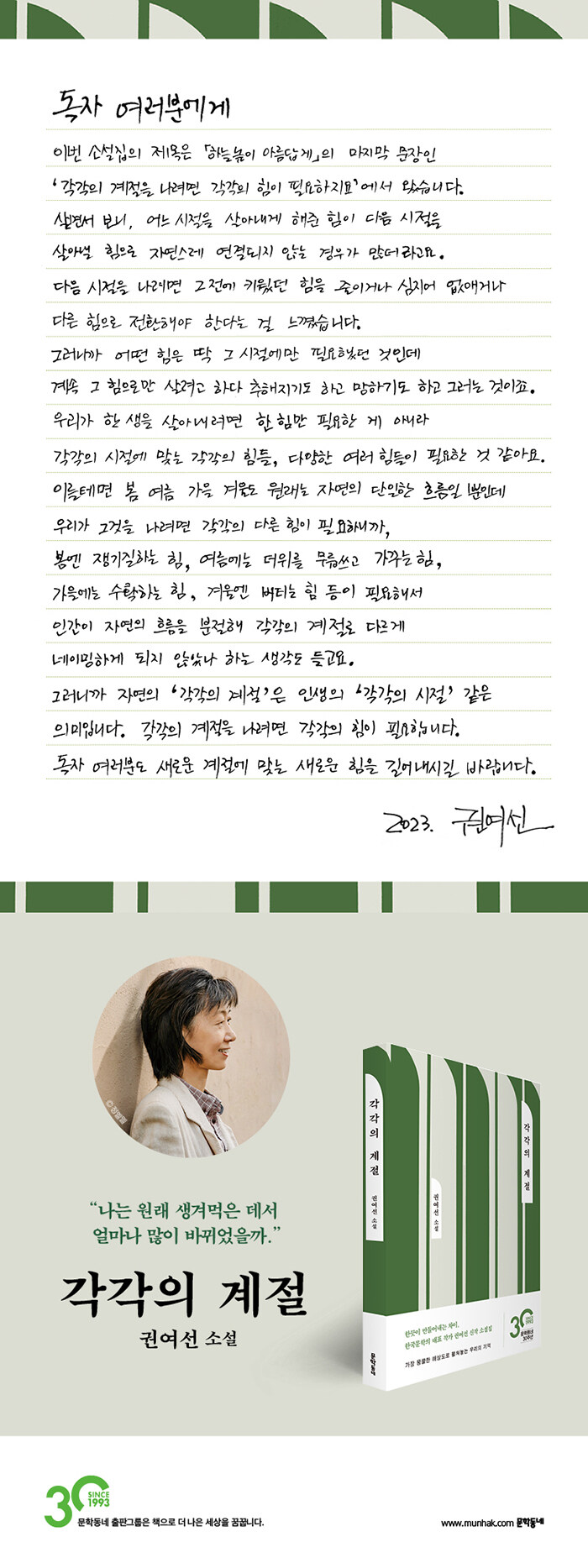

Kwon Yeo-seon's new work returns with a new season.A collection of short stories by novelist Kwon Yeo-seon, released after three years.

Seven works that have already been evaluated as masterpieces in the literary world have been compiled into one volume.

Novels that tenaciously and tenaciously hold onto forgotten times, an uncertain present, and an invisible future with beautiful prose and a sparkling gaze.

In the end, we are left to ask ourselves:

“Why me?”May 9, 2023. Novel/Poetry PD Kim Yu-ri

The difference it makes,

A new collection of short stories by Kwon Yeo-seon, a leading Korean literary author.

2021 Kim Yu-jeong Literary Award Winner, “Waltz of Memory”

2020 Kim Seung-ok Literary Award Excellence Award Winner, "Silver Thousand Things"

Included in the 2019 Kim Seung-ok Literary Award Excellence Award winner, "Beautifully High in the Sky"

Author Kwon Yeo-seon, who has become a trusted name in Korean literature by awakening the beauty of elegant yet rigorous sentences, is publishing a new collection of short stories, “Each Season,” after three years.

This is the seventh collection of short stories following 『Hello, Drunkard』(Changbi, 2016), which contains the heartbreaking voice of life that bursts out when alcohol and life combine, and 『Still Far Away』(Munhakdongne, 2020), which meticulously engraved reality with an uncompromising, straightforward approach. Seven works that were well-received even before being bound into a book have been gathered together like a comprehensive gift set for a spring day.

Debuting in 1996, Kwon Yeo-seon has dedicated herself to writing for over a quarter of a century, presenting works that have become the life's work of many. In this collection of short stories, she delves into the core of memory, emotion, and relationships, meticulously examining a period of time and a person.

The picture of life that is revealed through that process of direct observation is by no means bright.

But what is clear is that the process will lead us to a place where we desire a rich and vibrant life.

A new collection of short stories by Kwon Yeo-seon, a leading Korean literary author.

2021 Kim Yu-jeong Literary Award Winner, “Waltz of Memory”

2020 Kim Seung-ok Literary Award Excellence Award Winner, "Silver Thousand Things"

Included in the 2019 Kim Seung-ok Literary Award Excellence Award winner, "Beautifully High in the Sky"

Author Kwon Yeo-seon, who has become a trusted name in Korean literature by awakening the beauty of elegant yet rigorous sentences, is publishing a new collection of short stories, “Each Season,” after three years.

This is the seventh collection of short stories following 『Hello, Drunkard』(Changbi, 2016), which contains the heartbreaking voice of life that bursts out when alcohol and life combine, and 『Still Far Away』(Munhakdongne, 2020), which meticulously engraved reality with an uncompromising, straightforward approach. Seven works that were well-received even before being bound into a book have been gathered together like a comprehensive gift set for a spring day.

Debuting in 1996, Kwon Yeo-seon has dedicated herself to writing for over a quarter of a century, presenting works that have become the life's work of many. In this collection of short stories, she delves into the core of memory, emotion, and relationships, meticulously examining a period of time and a person.

The picture of life that is revealed through that process of direct observation is by no means bright.

But what is clear is that the process will lead us to a place where we desire a rich and vibrant life.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Stag Beetle Q&A… 007

Silver, ten million… 043

Beautifully high in the sky… 085

Mugu… 115

Blinker… 147

Mother can't sleep... 169

Waltz of Memory… 201

Commentary│Kwon Hee-cheol (literary critic)

Song of Eternal Return… 243

Silver, ten million… 043

Beautifully high in the sky… 085

Mugu… 115

Blinker… 147

Mother can't sleep... 169

Waltz of Memory… 201

Commentary│Kwon Hee-cheol (literary critic)

Song of Eternal Return… 243

Detailed image

Into the book

College freshmen who come to Seoul from the countryside are like ducklings thrown into an unfamiliar place, and they never forget the friends they made in their early days on campus.

---From "Stag Beetle-style Questions and Answers"

How did we end up like this?

We somehow ended up like this.

Since when did we become like this?

We've always been like this.

Whatever the reason, whatever the process, at some point we ended up like this.

After trying every trick for thirty years, it ended up like this.

What can I do? It's already come to this.

ah……

"Where did you come in?" "Come in wherever you want." The stag beetle's reply, "If you come in, you come in. You came in wherever you want. What should I do?" was hidden within its words a terrifying compulsion and a sharp blocking.

The cruel conciseness that forces us to face and accept any inevitability, no matter how heartbreaking, was embedded like a wedge in the single letter 'deun'.

---From "Stag Beetle-style Questions and Answers"

Since human self-rationalization tends to extend endlessly along irrational paths that others cannot possibly understand, self-rationalization is ultimately a contradiction.

Because self-rationalization is a mechanism that only works when one cannot rationalize oneself.

---From "Stag Beetle-style Questions and Answers"

Both attention and interference seem like violence.

It's like an insult.

My goal is to live safely and quietly, without being exposed to such things.

It's my last pride.

I want to live like that until I die.

---From "Silver's Ten Million"

If love is a nightmare, then Banhee thought, she might as well have a nightmare.

Let's share my daughter's nightmare.

If there are thousands and tens of thousands of threads connecting us, let's twist them into a rope and hold each other more tightly.

Let's get twisted, tough, and creepy together.

Let's turn our brains into jelly, bind our hearts, and dream deformed dreams.

Thoughts she had never experienced before welled up endlessly, and Banhee's heart raced as if something unbelievable had happened.

This forest, this bench, is really strange.

Then, just like last night, Banhee clenched her fists as if trying to hold onto this moment forever, and spoke softly as if telling herself to never forget it.

It's nothing, Chaeun.

They were nothing.

---From "Silver's Ten Million"

“It’s okay that I was born and lived like this, even though I never had a life in the first place, and I’ve had good times living, so it’s okay,” said Maria.

That's all I can thank God for, Madam.

I no longer seek God's grace.

---From "Beautifully High in the Sky"

Bertha felt like canceling her appointment with Maria because she had been unable to sleep all night that morning.

But once I decided to get up, I did, and as soon as I got up, I got out of bed.

When I told him to go to the bathroom, his feet moved towards the bathroom.

Strangely enough, it was just as Maria said.

If you coax your body to move, it will move, madam.

---From "Beautifully High in the Sky"

At that moment… …Hyunsu looked up at the sky and saw Somi.

We were young then… …and scared and afraid again.

---From "Innocent"

Some words, Oik thought, cause such repetitive side effects on the mind, just as certain foods cause repetitive allergic reactions in the human body.

The poison of the horse was far more lethal than the food.

You can avoid foods that cause allergic reactions if you have the will to do so, but you can't avoid words that cause negative reactions no matter how hard you try.

No, the stronger your will to avoid it, the more you become trapped by those words and unable to move.

My mother said that a debt is something that never disappears until it is paid off, that it is a debt that must be paid even after death.

Oik thought that was exactly what life was like.

The will to avoid and the impossibility of avoiding are directly proportional, and such terrifying words and things pile up like a primordial primordial.

---From "Mother Can't Sleep"

He didn't know that he was the kind of person who could instill such anger in someone close to him.

If I had known, would I have done that?

Ignorance is the most vulnerable target, but the ignorant are trembling in fear before attack, and because they are ignorant, they do not even know their sins and cannot even make a proper excuse.

---From "Mother Can't Sleep"

But the more I reflected on the past, the more surprising it was to realize that the me of that time seemed so unfamiliar, pitiful, and scary, like I wasn't myself at all.

The self in my old memories may have originally thought that way.

But even if it was originally like that, it is surprising.

It felt undeniable, yet unbelievable, to me that in a time and space so distant and beyond my control, I, then so young and strangely young, had lived in a way I never wanted, in a way I feared most, let alone desired.

If this isn't surprising, what is?

That time has made me such an outsider in my life, such a helpless spectator.

---From "Waltz of Memory"

I felt in his eyes, in his listening, that he was trying to read and interpret me with interest, and I was slowly becoming afraid.

On the one hand, I was afraid that he might dig up some fatal truth from within me, and on the other hand, I was afraid that he would get nothing out of me.

Those two were probably like two sides of the same coin.

But what I feared most of all was the despair that I would never be able to read him, this man called Gyeongseo.

---From "Waltz of Memory"

I kept my eyes tightly shut for a long time.

If only there had been someone who read and understood me, a gray spider who, long ago in my younger days, turned hope into despair and life into death with every passing moment.

No, if only I could have recognized that person, that person who recognized me, that person who patted my back and said, “Don’t do that, don’t do that,” and greeted me and turned around.

If that were the case, would that person have danced with me and told me that I was not a spider, that I was setting a trap for myself, that I didn't have to be content with such a small, hard crystal, that I could desire a richer, more vibrant life, that I should escape this web?

Did I listen to those words?

Did he realize what it meant and cry?

Could I have cried, not in front of the watermelon, but in front of the diary box, reading the letter suggesting we go to the forest restaurant on a day when two layers of dimensions meet in the same pattern?

---From "Stag Beetle-style Questions and Answers"

How did we end up like this?

We somehow ended up like this.

Since when did we become like this?

We've always been like this.

Whatever the reason, whatever the process, at some point we ended up like this.

After trying every trick for thirty years, it ended up like this.

What can I do? It's already come to this.

ah……

"Where did you come in?" "Come in wherever you want." The stag beetle's reply, "If you come in, you come in. You came in wherever you want. What should I do?" was hidden within its words a terrifying compulsion and a sharp blocking.

The cruel conciseness that forces us to face and accept any inevitability, no matter how heartbreaking, was embedded like a wedge in the single letter 'deun'.

---From "Stag Beetle-style Questions and Answers"

Since human self-rationalization tends to extend endlessly along irrational paths that others cannot possibly understand, self-rationalization is ultimately a contradiction.

Because self-rationalization is a mechanism that only works when one cannot rationalize oneself.

---From "Stag Beetle-style Questions and Answers"

Both attention and interference seem like violence.

It's like an insult.

My goal is to live safely and quietly, without being exposed to such things.

It's my last pride.

I want to live like that until I die.

---From "Silver's Ten Million"

If love is a nightmare, then Banhee thought, she might as well have a nightmare.

Let's share my daughter's nightmare.

If there are thousands and tens of thousands of threads connecting us, let's twist them into a rope and hold each other more tightly.

Let's get twisted, tough, and creepy together.

Let's turn our brains into jelly, bind our hearts, and dream deformed dreams.

Thoughts she had never experienced before welled up endlessly, and Banhee's heart raced as if something unbelievable had happened.

This forest, this bench, is really strange.

Then, just like last night, Banhee clenched her fists as if trying to hold onto this moment forever, and spoke softly as if telling herself to never forget it.

It's nothing, Chaeun.

They were nothing.

---From "Silver's Ten Million"

“It’s okay that I was born and lived like this, even though I never had a life in the first place, and I’ve had good times living, so it’s okay,” said Maria.

That's all I can thank God for, Madam.

I no longer seek God's grace.

---From "Beautifully High in the Sky"

Bertha felt like canceling her appointment with Maria because she had been unable to sleep all night that morning.

But once I decided to get up, I did, and as soon as I got up, I got out of bed.

When I told him to go to the bathroom, his feet moved towards the bathroom.

Strangely enough, it was just as Maria said.

If you coax your body to move, it will move, madam.

---From "Beautifully High in the Sky"

At that moment… …Hyunsu looked up at the sky and saw Somi.

We were young then… …and scared and afraid again.

---From "Innocent"

Some words, Oik thought, cause such repetitive side effects on the mind, just as certain foods cause repetitive allergic reactions in the human body.

The poison of the horse was far more lethal than the food.

You can avoid foods that cause allergic reactions if you have the will to do so, but you can't avoid words that cause negative reactions no matter how hard you try.

No, the stronger your will to avoid it, the more you become trapped by those words and unable to move.

My mother said that a debt is something that never disappears until it is paid off, that it is a debt that must be paid even after death.

Oik thought that was exactly what life was like.

The will to avoid and the impossibility of avoiding are directly proportional, and such terrifying words and things pile up like a primordial primordial.

---From "Mother Can't Sleep"

He didn't know that he was the kind of person who could instill such anger in someone close to him.

If I had known, would I have done that?

Ignorance is the most vulnerable target, but the ignorant are trembling in fear before attack, and because they are ignorant, they do not even know their sins and cannot even make a proper excuse.

---From "Mother Can't Sleep"

But the more I reflected on the past, the more surprising it was to realize that the me of that time seemed so unfamiliar, pitiful, and scary, like I wasn't myself at all.

The self in my old memories may have originally thought that way.

But even if it was originally like that, it is surprising.

It felt undeniable, yet unbelievable, to me that in a time and space so distant and beyond my control, I, then so young and strangely young, had lived in a way I never wanted, in a way I feared most, let alone desired.

If this isn't surprising, what is?

That time has made me such an outsider in my life, such a helpless spectator.

---From "Waltz of Memory"

I felt in his eyes, in his listening, that he was trying to read and interpret me with interest, and I was slowly becoming afraid.

On the one hand, I was afraid that he might dig up some fatal truth from within me, and on the other hand, I was afraid that he would get nothing out of me.

Those two were probably like two sides of the same coin.

But what I feared most of all was the despair that I would never be able to read him, this man called Gyeongseo.

---From "Waltz of Memory"

I kept my eyes tightly shut for a long time.

If only there had been someone who read and understood me, a gray spider who, long ago in my younger days, turned hope into despair and life into death with every passing moment.

No, if only I could have recognized that person, that person who recognized me, that person who patted my back and said, “Don’t do that, don’t do that,” and greeted me and turned around.

If that were the case, would that person have danced with me and told me that I was not a spider, that I was setting a trap for myself, that I didn't have to be content with such a small, hard crystal, that I could desire a richer, more vibrant life, that I should escape this web?

Did I listen to those words?

Did he realize what it meant and cry?

Could I have cried, not in front of the watermelon, but in front of the diary box, reading the letter suggesting we go to the forest restaurant on a day when two layers of dimensions meet in the same pattern?

---From "Waltz of Memory"

Publisher's Review

“How much have I changed from my original birth?”

What do we remember, how do we remember, why do we remember?

Why we became who we are today

Kwon Yeo-seon's deep and persistent questions

At the beginning and end of the collection of short stories, the "Stag Beetle-style Dialogue" and "Waltz of Memory," which both use "memory" as their main keyword, are placed side by side like a pair, enveloping "Each Season."

"The Stag Beetle-Style Dialogue," which depicts the shock and sadness felt when confronted with a truth that has long been ignored, is a brilliant work that takes Kwon Yeo-seon's long-standing theme of memory one step further.

“College freshmen who came up to Seoul from the countryside are like ducklings thrown into an unfamiliar space, and they cannot forget the friends they spent time with on campus for a long time” (p. 11), and so were ‘Junhee’, ‘Buyoung’, ‘Kyungae’, and ‘Jeongwon’.

The four of them enter university and live in the same boarding house. They drink together, share their daily lives, and become close.

The cool-headed Buyeong, the leader of the group, the disciplined and polite Gyeongae, the kind and cautious Jeongwon, and the novel's impromptu narrator Junhee, who loves alcohol, still try to meet at least once a month even after the year has passed and their living environments have changed, and they desperately celebrate each other's birthdays.

However, the path that the four people were beautifully drawing becomes tangled with Jeongwon's sudden suicide and Gyeongae's betrayal.

Unable to understand what made them this way and only knowing that they can never go back to the way things were, Junhee begins to look back on the past years with rigor and urgency.

And what is at the heart of that memory is the ‘stag beetle style question and answer.’

Long ago, on a trip the four of them took together, Jeongwon discovered a stag beetle in the inn and asked the owner about it.

There is a mosquito net, so where do stag beetles come in?

The owner hesitated for a moment and then answered:

Come in anywhere.

And then he left.

I was truly impressed by those words, which seemed to represent the stag beetle.

"Where are you coming in?" I asked, and it seemed as if I could hear the dignified voice of the stag beetle answering, "Come in wherever you want." (Page 21)

When asked where you came from, answer that you came from anywhere.

Junhee and Jeongwon call this conversation method of repeating each other's questions "stag beetle style" and think of it as a "magic button."

The reason they could think that way was probably because Junhee wanted to write a novel and Jeongwon wanted to do a play, in other words, both of them were in a situation where their futures were uncertain and imperfect.

The two people must have felt a certain freedom through this stag beetle-style dialogue, where they could simply say, "I want to write any novel, and I want to do any play," without having to explain in detail what kind of novel they wanted to write or what kind of play they wanted to do.

However, that refreshing and clear stag beetle-style dialogue gradually takes on a different meaning as Junhee looks back on the past.

There was a 'terrifying nuance' hidden in that answer that I couldn't read at the time.

"Where did you come in?" "Come in wherever you want." The stag beetle's reply, "If you come in, you come in. You came in wherever you want. What should I do?" was hidden within its words a terrifying compulsion and a sharp blocking.

The cruel conciseness that forces us to face and accept any inevitability, no matter how heartbreaking, is embedded like a wedge in the single word "deun." (p. 29)

But Kwon Yeo-seon doesn't stop here and goes on to figure out another meaning contained in the stag beetle-style dialogue.

Even if the process ends up hurting you.

If we borrow the words from the novel, “Those who do not face the truth will be punished by missing the target” (page 40), then by facing it, we can move to the position where we ourselves become the target.

“Waltz of Memory,” which was selected as the winner of the 2021 Kim Yu-jeong Literary Award with the comment that “it succeeded in a moving novelistic encounter with forgotten time by finding a miraculous moment that transforms the memory of an ashen shroud into a memory of a silver veil,” also features a character who clearly faces the past.

'I' went to a forest restaurant in the suburbs with my younger brother and sister-in-law and encountered memories from long ago, that is, from over thirty years ago.

At that time, when I was a college student, I lived my life thinking, “Today is the only sure thing I have in my hand, and I’ll just use that day as fuel to burn through time” (p. 211), when a man of the same age named Gyeongseo appears before me.

As I was walking down the library corridor, a senior I had met a few times at a drinking party called out to me, and that was when I first started talking to Gyeongseo, who was sitting next to him, and that's how our relationship began.

From that day on, Gyeongseo began to treat me kindly, and then one autumn day, I went on a short picnic with Gyeongseo, Guseonbae, and others to a restaurant in the suburbs.

That restaurant was the forest restaurant that the current 'me' had visited with my younger brother and sister-in-law.

Until now, I had not harbored any special feelings for Gyeongseo, that it was “an ambiguous relationship that made me wonder if it could even be called a relationship” (p. 209), and that Gyeongseo was largely responsible for their growing estrangement after the picnic. But now, after visiting the forest restaurant, memories from thirty years ago, layered with errors and evasions, rise up before me anew.

The process of recalling memories inevitably involves distortion and embellishment.

However, Kwon Yeo-seon's characters suppress their desire for self-rationalization as if removing impurities, and slowly, deeply, and persistently point out the mistakes and errors they may have made.

And the memories that are seen after going through that process unexpectedly give the characters something different, like a gift.

In “Waltz of Memory,” as I look back on my twenties, a time when I “lived by turning hope into despair and life into death at every opportunity” (p. 241), I also recall the comforting gestures I received from Gyeongseo during that time.

As such, it is possible to say, “It is too early to give up hope” (same side).

And that would be 'living twice (differently) while remembering, and living three times (differently) while writing the memories' (Kwon Yeo-seon, from the special booklet 'Attention Book').

Helplessness of memory, helplessness of emotions, helplessness of relationships

Kwon Yeo-seon's seasonal novels that instantly disarm us

The title of the collection of short stories, “Each Season,” comes from the sentence “Each season requires its own strength” (page 114) in “Beautifully High in the Sky.”

"Beautifully High in the Sky" reconstructs what kind of person Maria was by showing the congregation of the church recalling her death from illness at the age of seventy-two.

The believers lament Mary's death, each competing to tell of the image of Mary they remember, but their gaze contains a subtle exclusivity that places Mary below themselves.

Bertha also feels their hypocrisy keenly, thinking, “How ungrateful these people are” (p. 91).

The question then is, “Why do I continue to meet with them?” (p. 91).

The answer to that question is impressively depicted at the end of the novel.

Bertha had accompanied Maria before she died, but when she was stabbed in the eye by a woman's parasol, she collapsed. When Maria hurriedly approached her and tried to examine her eye, Bertha pushed her away after smelling her bad breath.

Bertha, recalling that scene, thinks, “I clearly understand why I continued to meet with them” (p. 114).

“We are not noble at all...” (Same side) But perhaps ‘nobility’ begins there.

From looking deeply into oneself with those merciless, strict eyes that judge others.

And through that process, Mary will be revealed in a different form than the one that was completed by the churchgoers by piecing together pieces like a puzzle.

The title of the collection of short stories, which can be read as meaning that a new season requires new strength to suit the season, seems to apply not only to the seasons but also to the characters.

What if we looked at the mother and daughter, who are particularly tied together more tenaciously and tightly than any other relationship, from the perspective of 'each season'?

One day, Ban-hee, from "Silver's Ten Million," receives a call from her daughter, Chae-woon, when the gym she was working at was closed due to COVID-19.

Let's go on a two-day, one-night trip to a nearby place together.

Banhee, who lives separately from Chaewoon after their divorce, is somewhat surprised by the proposal.

This is because Banhee “didn’t want Chae-woon to resemble herself”, “if there is an invisible thread of resemblance between them, I want to cut it off no matter how many thousands or tens of thousands of those threads there are” (p. 50), and because she wanted to protect Chae-woon as a unique individual rather than bind her with a close mother-daughter relationship, so she kept a certain distance from her daughter.

To Ban-hee, who was hesitating, Chae-woon suddenly started talking quickly and said, “There’s a pension he knows deep in the mountains of Gangwon-do. You can just drive there and come back. You can even cook there, so there’s no need to go out. Wouldn’t it be okay if you just hide there, don’t meet anyone, just take a walk around the area, and spend just one day like that?” (pp. 49-50), pouring out his words as if he expected Ban-hee to refuse.

So the two go on a trip together for the first time, and decide to call each other 'Banhee' and 'Chaewoon' instead of mother and daughter.

This act of protecting each other as individuals rather than as family roles seems to signal a refreshing start to the journey.

But during their trip, the two suddenly realize that this may be an act that hurts each other.

To Banhee, Chaewoon is not just a daughter who needs to be constantly looked after and checked, and to Chaewoon, Banhee is not just a mother who left her when she was young.

Banhee put out her cigarette and clasped her hands together.

As the wind blew by, the strong scent of earth and grass wafted through.

If love is a nightmare, then Banhee thought, she might as well have a nightmare.

Let's share my daughter's nightmare.

If there are thousands and tens of thousands of threads connecting us, let's twist them into a rope and hold each other more tightly.

Let's get twisted, tough, and creepy together.

Let's turn our brains into jelly, bind our hearts, and dream deformed dreams.

Thoughts she had never experienced before surged forth endlessly, and Banhee's heart raced as if something unbelievable were happening. (Page 79)

Instead of cutting the tens of thousands of threads that connect us, we twist them into a rope and connect them more tightly.

This unexpected yet natural transition seems to resemble the change of seasons.

Just as the seasons change and the strength needed changes, the two people will now look at each other with different eyes than before.

And only then will they be able to see a new season unfold before them, different from the past.

Just as we can gain the strength to conclude the current season and move on to the next by dividing the connected flow of time into spring, summer, fall, and winter, what Kwon Yeo-seon is giving us seems to be a new season that we need now, that is, 'each season.'

What do we remember, how do we remember, why do we remember?

Why we became who we are today

Kwon Yeo-seon's deep and persistent questions

At the beginning and end of the collection of short stories, the "Stag Beetle-style Dialogue" and "Waltz of Memory," which both use "memory" as their main keyword, are placed side by side like a pair, enveloping "Each Season."

"The Stag Beetle-Style Dialogue," which depicts the shock and sadness felt when confronted with a truth that has long been ignored, is a brilliant work that takes Kwon Yeo-seon's long-standing theme of memory one step further.

“College freshmen who came up to Seoul from the countryside are like ducklings thrown into an unfamiliar space, and they cannot forget the friends they spent time with on campus for a long time” (p. 11), and so were ‘Junhee’, ‘Buyoung’, ‘Kyungae’, and ‘Jeongwon’.

The four of them enter university and live in the same boarding house. They drink together, share their daily lives, and become close.

The cool-headed Buyeong, the leader of the group, the disciplined and polite Gyeongae, the kind and cautious Jeongwon, and the novel's impromptu narrator Junhee, who loves alcohol, still try to meet at least once a month even after the year has passed and their living environments have changed, and they desperately celebrate each other's birthdays.

However, the path that the four people were beautifully drawing becomes tangled with Jeongwon's sudden suicide and Gyeongae's betrayal.

Unable to understand what made them this way and only knowing that they can never go back to the way things were, Junhee begins to look back on the past years with rigor and urgency.

And what is at the heart of that memory is the ‘stag beetle style question and answer.’

Long ago, on a trip the four of them took together, Jeongwon discovered a stag beetle in the inn and asked the owner about it.

There is a mosquito net, so where do stag beetles come in?

The owner hesitated for a moment and then answered:

Come in anywhere.

And then he left.

I was truly impressed by those words, which seemed to represent the stag beetle.

"Where are you coming in?" I asked, and it seemed as if I could hear the dignified voice of the stag beetle answering, "Come in wherever you want." (Page 21)

When asked where you came from, answer that you came from anywhere.

Junhee and Jeongwon call this conversation method of repeating each other's questions "stag beetle style" and think of it as a "magic button."

The reason they could think that way was probably because Junhee wanted to write a novel and Jeongwon wanted to do a play, in other words, both of them were in a situation where their futures were uncertain and imperfect.

The two people must have felt a certain freedom through this stag beetle-style dialogue, where they could simply say, "I want to write any novel, and I want to do any play," without having to explain in detail what kind of novel they wanted to write or what kind of play they wanted to do.

However, that refreshing and clear stag beetle-style dialogue gradually takes on a different meaning as Junhee looks back on the past.

There was a 'terrifying nuance' hidden in that answer that I couldn't read at the time.

"Where did you come in?" "Come in wherever you want." The stag beetle's reply, "If you come in, you come in. You came in wherever you want. What should I do?" was hidden within its words a terrifying compulsion and a sharp blocking.

The cruel conciseness that forces us to face and accept any inevitability, no matter how heartbreaking, is embedded like a wedge in the single word "deun." (p. 29)

But Kwon Yeo-seon doesn't stop here and goes on to figure out another meaning contained in the stag beetle-style dialogue.

Even if the process ends up hurting you.

If we borrow the words from the novel, “Those who do not face the truth will be punished by missing the target” (page 40), then by facing it, we can move to the position where we ourselves become the target.

“Waltz of Memory,” which was selected as the winner of the 2021 Kim Yu-jeong Literary Award with the comment that “it succeeded in a moving novelistic encounter with forgotten time by finding a miraculous moment that transforms the memory of an ashen shroud into a memory of a silver veil,” also features a character who clearly faces the past.

'I' went to a forest restaurant in the suburbs with my younger brother and sister-in-law and encountered memories from long ago, that is, from over thirty years ago.

At that time, when I was a college student, I lived my life thinking, “Today is the only sure thing I have in my hand, and I’ll just use that day as fuel to burn through time” (p. 211), when a man of the same age named Gyeongseo appears before me.

As I was walking down the library corridor, a senior I had met a few times at a drinking party called out to me, and that was when I first started talking to Gyeongseo, who was sitting next to him, and that's how our relationship began.

From that day on, Gyeongseo began to treat me kindly, and then one autumn day, I went on a short picnic with Gyeongseo, Guseonbae, and others to a restaurant in the suburbs.

That restaurant was the forest restaurant that the current 'me' had visited with my younger brother and sister-in-law.

Until now, I had not harbored any special feelings for Gyeongseo, that it was “an ambiguous relationship that made me wonder if it could even be called a relationship” (p. 209), and that Gyeongseo was largely responsible for their growing estrangement after the picnic. But now, after visiting the forest restaurant, memories from thirty years ago, layered with errors and evasions, rise up before me anew.

The process of recalling memories inevitably involves distortion and embellishment.

However, Kwon Yeo-seon's characters suppress their desire for self-rationalization as if removing impurities, and slowly, deeply, and persistently point out the mistakes and errors they may have made.

And the memories that are seen after going through that process unexpectedly give the characters something different, like a gift.

In “Waltz of Memory,” as I look back on my twenties, a time when I “lived by turning hope into despair and life into death at every opportunity” (p. 241), I also recall the comforting gestures I received from Gyeongseo during that time.

As such, it is possible to say, “It is too early to give up hope” (same side).

And that would be 'living twice (differently) while remembering, and living three times (differently) while writing the memories' (Kwon Yeo-seon, from the special booklet 'Attention Book').

Helplessness of memory, helplessness of emotions, helplessness of relationships

Kwon Yeo-seon's seasonal novels that instantly disarm us

The title of the collection of short stories, “Each Season,” comes from the sentence “Each season requires its own strength” (page 114) in “Beautifully High in the Sky.”

"Beautifully High in the Sky" reconstructs what kind of person Maria was by showing the congregation of the church recalling her death from illness at the age of seventy-two.

The believers lament Mary's death, each competing to tell of the image of Mary they remember, but their gaze contains a subtle exclusivity that places Mary below themselves.

Bertha also feels their hypocrisy keenly, thinking, “How ungrateful these people are” (p. 91).

The question then is, “Why do I continue to meet with them?” (p. 91).

The answer to that question is impressively depicted at the end of the novel.

Bertha had accompanied Maria before she died, but when she was stabbed in the eye by a woman's parasol, she collapsed. When Maria hurriedly approached her and tried to examine her eye, Bertha pushed her away after smelling her bad breath.

Bertha, recalling that scene, thinks, “I clearly understand why I continued to meet with them” (p. 114).

“We are not noble at all...” (Same side) But perhaps ‘nobility’ begins there.

From looking deeply into oneself with those merciless, strict eyes that judge others.

And through that process, Mary will be revealed in a different form than the one that was completed by the churchgoers by piecing together pieces like a puzzle.

The title of the collection of short stories, which can be read as meaning that a new season requires new strength to suit the season, seems to apply not only to the seasons but also to the characters.

What if we looked at the mother and daughter, who are particularly tied together more tenaciously and tightly than any other relationship, from the perspective of 'each season'?

One day, Ban-hee, from "Silver's Ten Million," receives a call from her daughter, Chae-woon, when the gym she was working at was closed due to COVID-19.

Let's go on a two-day, one-night trip to a nearby place together.

Banhee, who lives separately from Chaewoon after their divorce, is somewhat surprised by the proposal.

This is because Banhee “didn’t want Chae-woon to resemble herself”, “if there is an invisible thread of resemblance between them, I want to cut it off no matter how many thousands or tens of thousands of those threads there are” (p. 50), and because she wanted to protect Chae-woon as a unique individual rather than bind her with a close mother-daughter relationship, so she kept a certain distance from her daughter.

To Ban-hee, who was hesitating, Chae-woon suddenly started talking quickly and said, “There’s a pension he knows deep in the mountains of Gangwon-do. You can just drive there and come back. You can even cook there, so there’s no need to go out. Wouldn’t it be okay if you just hide there, don’t meet anyone, just take a walk around the area, and spend just one day like that?” (pp. 49-50), pouring out his words as if he expected Ban-hee to refuse.

So the two go on a trip together for the first time, and decide to call each other 'Banhee' and 'Chaewoon' instead of mother and daughter.

This act of protecting each other as individuals rather than as family roles seems to signal a refreshing start to the journey.

But during their trip, the two suddenly realize that this may be an act that hurts each other.

To Banhee, Chaewoon is not just a daughter who needs to be constantly looked after and checked, and to Chaewoon, Banhee is not just a mother who left her when she was young.

Banhee put out her cigarette and clasped her hands together.

As the wind blew by, the strong scent of earth and grass wafted through.

If love is a nightmare, then Banhee thought, she might as well have a nightmare.

Let's share my daughter's nightmare.

If there are thousands and tens of thousands of threads connecting us, let's twist them into a rope and hold each other more tightly.

Let's get twisted, tough, and creepy together.

Let's turn our brains into jelly, bind our hearts, and dream deformed dreams.

Thoughts she had never experienced before surged forth endlessly, and Banhee's heart raced as if something unbelievable were happening. (Page 79)

Instead of cutting the tens of thousands of threads that connect us, we twist them into a rope and connect them more tightly.

This unexpected yet natural transition seems to resemble the change of seasons.

Just as the seasons change and the strength needed changes, the two people will now look at each other with different eyes than before.

And only then will they be able to see a new season unfold before them, different from the past.

Just as we can gain the strength to conclude the current season and move on to the next by dividing the connected flow of time into spring, summer, fall, and winter, what Kwon Yeo-seon is giving us seems to be a new season that we need now, that is, 'each season.'

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: May 7, 2023

- Pages, weight, size: 276 pages | 359g | 133*200*20mm

- ISBN13: 9788954692526

- ISBN10: 8954692524

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)