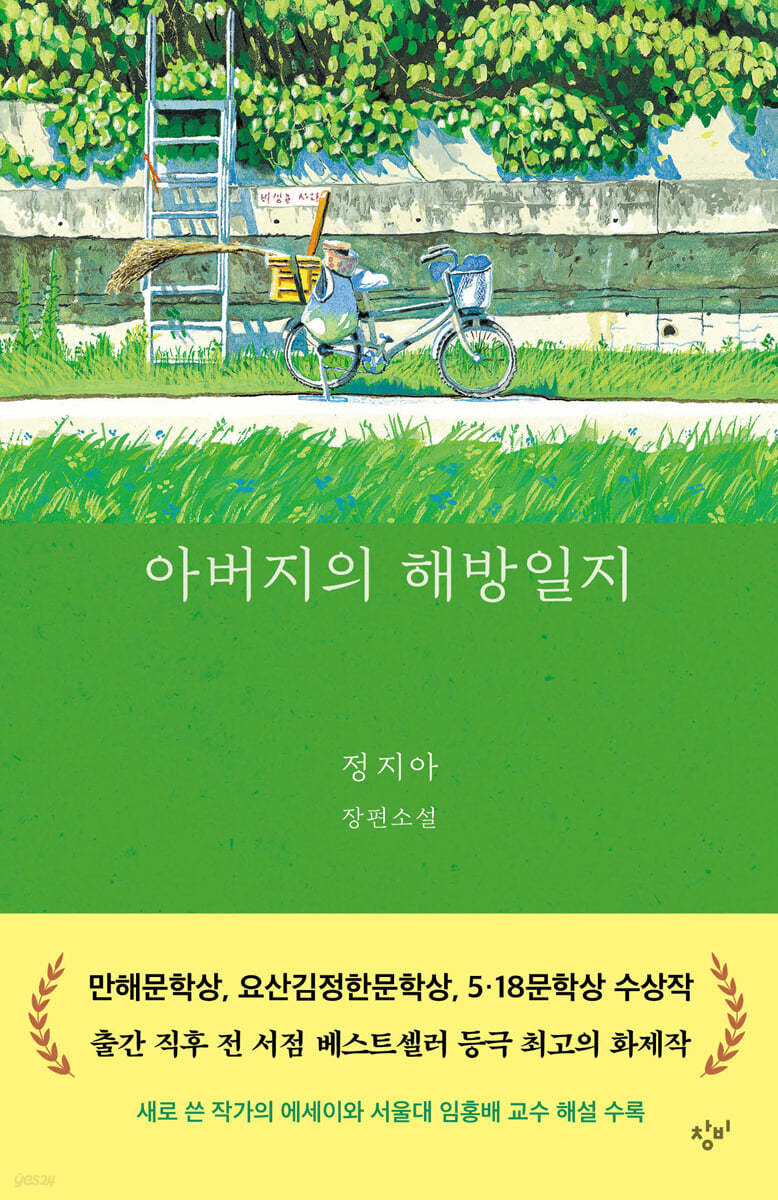

Father's Liberation Diary

|

Description

Book Introduction

- A word from MD

-

A story of life that begins with deathThe novel begins with the sentence, 'My father died.'

During the three days following the funeral of his father, a former guerrilla, his time is closely intertwined with the people and words that come and go.

A story of life that makes you cry and laugh and feel warm as you read, with your deeply entangled feelings pouring out.September 16, 2022. Novel/Poetry PD Park Hyung-wook

I am amazed once again!

Overwhelming immersion, heart-wrenching emotion

The warmth of the times unfolding through Jeong Ji-ah's fingertips

The turbulent history of a mysterious man

The ultimately strong life we discover within it

Jeong Ji-ah, a realist who has proven her literary talent by winning awards such as the Kim Yu-jeong Literary Award, the Sim Hun Literary Award, and the Lee Hyo-seok Literary Award, has published a full-length novel after 32 years.

The author, who has received praise from readers and critics alike for his accurate depiction of life in each of his works, presents a masterpiece that weaves together the scars of history and the love of family, offering a refreshing sip of solace to readers thirsty for bold narratives.

Jeong Ji-ah, who has repeatedly presented “a new narrative style for Korean novels” (literary critic Jeong Hong-su) with her outstanding linguistic skills, returns to her original intentions and tackles the story of her father, following the work “The Partisan’s Daughter” (1990), which was a sensation for a time.

The novel covers only the three days following the death of the father, a former guerrilla fighter, but as we follow the tangled story unfolding at the funeral, the twists and turns of modern history over the past 70 years since liberation are vividly revealed.

It is the narrative ability of Jeong Ji-ah that alone can provide such a grand scale and an immersive experience that makes it impossible to put it down.

But perhaps the true charm of this novel lies in its ‘lightness.’

“My father died.

(…) Readers will get the sense from the first chapter, which begins with “What the hell,” but despite its serious themes, this book is not a serious novel.

The anecdotes told in the savory language of the southern region are each sad, yet humorous, and “the words ‘You are a positive person’ warm the heart instead of making one feel angry” (Recommendation, Kim Mi-wol).

Overwhelming immersion, heart-wrenching emotion

The warmth of the times unfolding through Jeong Ji-ah's fingertips

The turbulent history of a mysterious man

The ultimately strong life we discover within it

Jeong Ji-ah, a realist who has proven her literary talent by winning awards such as the Kim Yu-jeong Literary Award, the Sim Hun Literary Award, and the Lee Hyo-seok Literary Award, has published a full-length novel after 32 years.

The author, who has received praise from readers and critics alike for his accurate depiction of life in each of his works, presents a masterpiece that weaves together the scars of history and the love of family, offering a refreshing sip of solace to readers thirsty for bold narratives.

Jeong Ji-ah, who has repeatedly presented “a new narrative style for Korean novels” (literary critic Jeong Hong-su) with her outstanding linguistic skills, returns to her original intentions and tackles the story of her father, following the work “The Partisan’s Daughter” (1990), which was a sensation for a time.

The novel covers only the three days following the death of the father, a former guerrilla fighter, but as we follow the tangled story unfolding at the funeral, the twists and turns of modern history over the past 70 years since liberation are vividly revealed.

It is the narrative ability of Jeong Ji-ah that alone can provide such a grand scale and an immersive experience that makes it impossible to put it down.

But perhaps the true charm of this novel lies in its ‘lightness.’

“My father died.

(…) Readers will get the sense from the first chapter, which begins with “What the hell,” but despite its serious themes, this book is not a serious novel.

The anecdotes told in the savory language of the southern region are each sad, yet humorous, and “the words ‘You are a positive person’ warm the heart instead of making one feel angry” (Recommendation, Kim Mi-wol).

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Father's Liberation Diary

Author's Note

Author's Note

Detailed image

Into the book

My father died.

Hit your head on the telephone pole.

My father, who had lived his entire life with a serious expression, ended his serious life by hitting his head on a telephone pole.

It wasn't April Fool's Day.

Even though it was April Fool's Day, it wasn't a household where such pranks or jokes were played around.

Humor.

Humor was something of a taboo in our house.

That doesn't mean there wasn't any humor.

Even in moments that anyone could tell were humorous and should have been, my parents were serious, like revolutionaries on the verge of revolution, and that made people laugh.

--- p.7

My name is Ari, which sounds like a dog's name.

I suffered from many measles thanks to the names of Baek-A-San, where my father was active, and Ji-Ri, where my mother was active (in fact, the place where my father was active was Baekun-San rather than Baek-A-San.

However, the reason why Baek Ah-san was named after Baek or Un of Baekun-san was because Baek or Un of Baekun-san was not suitable as a girl's name. In other words, no matter how much gender equality was advocated, it was an expression of semi-feudal thinking that was born in a semi-feudal era and could not completely escape the shadow of patriarchy.

At school or in government offices, when I said my name, Goari, people would look at me and say, "Wow, your name is really pretty, and your face is pretty too..." and soon an ellipsis followed.

--- p.29

I was satisfied with the materialist answer.

“Then what about the sacrifice?”

“The governor is a god.

“I wonder if you have a lot of rinses, so why don’t you show your face as an excuse? What kind of governor is this Honchandi?”

My father was a materialist to the core.

He was an unfilial son who couldn't even think about taking a picture of his parents' memorial tablet, let alone preparing a burial site for them even though they were over eighty years old, but since that was his father's will, he had to follow it.

After all, materialism is refreshing and good.

--- p.94

“Why would you call me in the middle of the night!” That was the bastard’s complaint again.

“How can a person be like that?” was my father’s eighteenth comment.

Unlike my father, I didn't trust the heart that was looking for him.

When times are tough, people tend to look for the people they trust the most or find easiest to trust.

Either way, the result is the same.

There are not even one in ten people who can keep the heart of someone who helped them in difficult times for their entire life.

Usually, it is the person who receives help who forgets the favor before the person who gave it.

--- p.102

“Work…work…is hard.”

Until then, I had been holding on tight and barely able to hold on, but when the guerrillas confessed that the work was hard, I burst out laughing.

He added with a wry smile, as if he himself had no shame.

“I worked hard for three days and was hospitalized for three months.

“No matter what I do, I can’t get along with labor.”

“That bourgeois mentality won’t be uprooted even if his hair turns gray.

How can a guy like that be a punk… … ”

--- p.150

He said he lost his leg in the Vietnam War, so it must have been in his late sixties or early seventies, and perhaps because he had been using his leg longer than his original leg, the old man moved his cane skillfully and approached me without even stumbling.

“Oh, what’s with the condolence… I’ll have a drink with you.”

It was impossible to just grab the old man with a bad leg, so Mr. Hwang couldn't do anything but follow him and urge him on.

“Why? I’m the one who defeated the Viet Cong, so why can’t I come and pay my respects to the Pol Gang? Didn’t Go Sang-wook defeat them?”

--- p.193

“If your daughter smokes, she’s a bitch. If my daughter smokes, she’s curious? That’s the essence of petty bourgeoisness! What kind of person can someone who can’t overcome petty bourgeoisness do?” At that time, my mother was over sixty years old.

I left, thinking to myself, "What kind of revolution are these communists over 60 trying to carry out in capitalist South Korea? This is a true black comedy."

I desperately wanted a cigarette.

Just to smoke a cigarette, I climbed up to a mountainside where the locals never went.

Our house, seen through generations of cigarette smoke, looked like a matchbox.

Hit your head on the telephone pole.

My father, who had lived his entire life with a serious expression, ended his serious life by hitting his head on a telephone pole.

It wasn't April Fool's Day.

Even though it was April Fool's Day, it wasn't a household where such pranks or jokes were played around.

Humor.

Humor was something of a taboo in our house.

That doesn't mean there wasn't any humor.

Even in moments that anyone could tell were humorous and should have been, my parents were serious, like revolutionaries on the verge of revolution, and that made people laugh.

--- p.7

My name is Ari, which sounds like a dog's name.

I suffered from many measles thanks to the names of Baek-A-San, where my father was active, and Ji-Ri, where my mother was active (in fact, the place where my father was active was Baekun-San rather than Baek-A-San.

However, the reason why Baek Ah-san was named after Baek or Un of Baekun-san was because Baek or Un of Baekun-san was not suitable as a girl's name. In other words, no matter how much gender equality was advocated, it was an expression of semi-feudal thinking that was born in a semi-feudal era and could not completely escape the shadow of patriarchy.

At school or in government offices, when I said my name, Goari, people would look at me and say, "Wow, your name is really pretty, and your face is pretty too..." and soon an ellipsis followed.

--- p.29

I was satisfied with the materialist answer.

“Then what about the sacrifice?”

“The governor is a god.

“I wonder if you have a lot of rinses, so why don’t you show your face as an excuse? What kind of governor is this Honchandi?”

My father was a materialist to the core.

He was an unfilial son who couldn't even think about taking a picture of his parents' memorial tablet, let alone preparing a burial site for them even though they were over eighty years old, but since that was his father's will, he had to follow it.

After all, materialism is refreshing and good.

--- p.94

“Why would you call me in the middle of the night!” That was the bastard’s complaint again.

“How can a person be like that?” was my father’s eighteenth comment.

Unlike my father, I didn't trust the heart that was looking for him.

When times are tough, people tend to look for the people they trust the most or find easiest to trust.

Either way, the result is the same.

There are not even one in ten people who can keep the heart of someone who helped them in difficult times for their entire life.

Usually, it is the person who receives help who forgets the favor before the person who gave it.

--- p.102

“Work…work…is hard.”

Until then, I had been holding on tight and barely able to hold on, but when the guerrillas confessed that the work was hard, I burst out laughing.

He added with a wry smile, as if he himself had no shame.

“I worked hard for three days and was hospitalized for three months.

“No matter what I do, I can’t get along with labor.”

“That bourgeois mentality won’t be uprooted even if his hair turns gray.

How can a guy like that be a punk… … ”

--- p.150

He said he lost his leg in the Vietnam War, so it must have been in his late sixties or early seventies, and perhaps because he had been using his leg longer than his original leg, the old man moved his cane skillfully and approached me without even stumbling.

“Oh, what’s with the condolence… I’ll have a drink with you.”

It was impossible to just grab the old man with a bad leg, so Mr. Hwang couldn't do anything but follow him and urge him on.

“Why? I’m the one who defeated the Viet Cong, so why can’t I come and pay my respects to the Pol Gang? Didn’t Go Sang-wook defeat them?”

--- p.193

“If your daughter smokes, she’s a bitch. If my daughter smokes, she’s curious? That’s the essence of petty bourgeoisness! What kind of person can someone who can’t overcome petty bourgeoisness do?” At that time, my mother was over sixty years old.

I left, thinking to myself, "What kind of revolution are these communists over 60 trying to carry out in capitalist South Korea? This is a true black comedy."

I desperately wanted a cigarette.

Just to smoke a cigarette, I climbed up to a mountainside where the locals never went.

Our house, seen through generations of cigarette smoke, looked like a matchbox.

--- p.243

Publisher's Review

Sitcom-like anecdotes

To understand my father

My father was a guerrilla who crossed Jirisan and Baekunsan with a carbine rifle.

He fought for an equal world immediately after the end of Japanese colonial rule, but was defeated miserably.

His comrades died one by one, and his father tried to rebuild the organization through disguise, but even that failed.

Nevertheless, my father lived his entire life as a socialist in capitalist Korea.

He never gave up on the belief that an equal world would come, and he never ignored the difficulties faced by complete strangers.

Not only do I not understand such a father, I also find him a bit ridiculous.

In a world where everyone eats their fill and is educated without discrimination, the sight of a father acting as if he is on the verge of revolution is close to black comedy to anyone who sees it.

‘I’ and my father, who have been running parallel lines like that.

That father died.

On Labor Day dawn, I hit my head on a telephone pole.

This story is largely divided into four parts.

The first is the story of his uncle, his younger brother, who had been at odds with his father his entire life.

My uncle, who believes that his family was ruined because of his 'red' brother, is so cold that he hangs up on me without answering the phone when I call to inform him of my brother's death.

My uncle, who had been a lifelong drinker, would sometimes come to my house and act up, saying things like, “Are you so great that you ruined the family?” (page 38).

Every time, my father did not fight back and remained silent without answering.

I'd rather my uncle not show up at the funeral.

Whether he will appear or not is a matter of interest to everyone gathered at the funeral, and readers also watch with interest and curiosity throughout the book.

Can my dead father and my living uncle reconcile?

The second is a story about the friends my father made in Gurye.

Their faces are so diverse and three-dimensional that just looking at them feels like watching a sitcom.

Mr. Park, a classmate of my father's from elementary school and owner of a watch shop.

He is my father's best friend, even though they are polar opposites, having spent his entire life as a soldier and a drill instructor.

The bickering between the two old men due to their differences in political orientation is somehow cute, and the line at the end, “Still, people should be the best” (page 47), makes me think that today’s political world should learn from it.

And a girl with bright yellow hair who appeared out of place at this funeral.

For some reason, he is said to be his father's "cigarette buddy" (page 139).

It is only possible for a father to become friendly with a seventeen-year-old girl, but the character of the father who does not forget to talk about 'American imperialism' to the girl whose mother is Vietnamese still makes people laugh.

In addition, many people who claim to be the father's sons, including 'Haksu', and the unfortunate stories of those who fought with guns but eventually became friends, appear one after another.

Is the father I knew real?

The countless episodes he left behind

The third is the story of 'me' and my father.

The main plot of ‘Father’s Liberation Diary’ is the process by which the daughter, who has lived a difficult life as the ‘daughter of a guerrilla,’ comes to understand her father.

Because he was a socialist and a revolutionary fighter, he had no ability to make a living, and because he did not hesitate to “guarantee” (page 57) for such a situation, the family’s poverty was always the fault of his father.

The long-winded stories my father would tell me without any warning were out of touch with reality, and that's why I wanted to leave my hometown where my father was.

But after my father's death, 'I' realized that the face of my father that I knew was only a small part of it.

The father's rational and realistic side is revealed, as well as his boldness that inspired people.

More than anything, I remember the moments when I loved myself, which I had forgotten.

Finally, 'I' hold my father's remains in my hands and decide to send him off in the most fatherly way possible.

The fourth and final one is anecdotes between mother and father.

They add a lively touch to the weight of the narrative and make readers laugh.

His mother, a lifelong comrade and also a socialist, was more realistic than his father.

So my father is always being bullied for one reason or another.

There are relatively minor things like not being able to quit drinking and smoking because you don't wash your clothes, and there are also major things like being forced to give up farming because you had to guarantee a loan.

In some ways, these people, who seem like enemies, become one in a devout manner in front of 'materialism' and 'nation', and this comical 'tiki-taka' becomes a pleasant catalyst for understanding the father's life.

"The Daughter of the Guerillas, the Daughter of Korean Literature"

The sensation called Jung Ji-ah

The appearance of Jeong Ji-ah 32 years ago was a sensation in Korean literature.

It was not because of a series of incidents such as the ban on sales and the prosecution by the public security authorities, but because of the vivid descriptions he showed and his serious attitude toward history.

Now, in addition to that attitude, Jeong Ji-ah has the composure to freely tell a story by mixing fact and fiction, and the appearance of a master who holds the reader's hand tightly until the last page.

This is precisely why I expect that Jeong Ji-ah will once again prove her presence with this novel, released after 32 years.

Everyone who loves Korean literature should listen to the words of novelist Kim Mi-wol, “Jeong Ji-ah is not only the daughter of a guerrilla, but also a precious daughter of our literature.”

Author's Note

When I returned to my hometown, I saw a world of beauty that I had never seen in Seoul.

The cherry blossom road along the Seomjin River, the sunset at Banyabong Peak, and the sea of clouds at Nogodan are not the only beautiful things.

The neighborhood old lady who says she really hates cherry blossoms and cornelian cherry blossoms, the restaurant owner who insists on bringing you food even though you don't need it, saying that you need to eat it to gain strength, the market old lady who lied and sold you tough vegetables that you couldn't eat by saying that they would become soft if you boiled them, and the restaurant owner who yelled at me to sit at the table furthest from the kitchen even though there was no one there (it turned out she had severe arthritis). This place is full of people who smell like people.

Why else would the old lady lie?

It's all about eating and living.

When in a hurry, isn't it human to lie and yell?

How can a person be so stubborn?

Father, it was number eighteen.

When I accept those words, the world becomes so beautiful.

I should have listened to my father a long time ago.

father.

Father, daughter, I have lived wrongly for so long.

Still, since I knew it before my sixtieth birthday, it's better than never knowing, right? I understand that you gave birth to me as a great man, and as a woman of humble character, so please forgive my past arrogance, rudeness, and foolishness... Thank you, Father.

I am saying this easy thing to a child now, just before my 60th birthday, after my father passed away.

What can I do? That's my father's daughter.

This ugly daughter dedicates this book to her father.

To understand my father

My father was a guerrilla who crossed Jirisan and Baekunsan with a carbine rifle.

He fought for an equal world immediately after the end of Japanese colonial rule, but was defeated miserably.

His comrades died one by one, and his father tried to rebuild the organization through disguise, but even that failed.

Nevertheless, my father lived his entire life as a socialist in capitalist Korea.

He never gave up on the belief that an equal world would come, and he never ignored the difficulties faced by complete strangers.

Not only do I not understand such a father, I also find him a bit ridiculous.

In a world where everyone eats their fill and is educated without discrimination, the sight of a father acting as if he is on the verge of revolution is close to black comedy to anyone who sees it.

‘I’ and my father, who have been running parallel lines like that.

That father died.

On Labor Day dawn, I hit my head on a telephone pole.

This story is largely divided into four parts.

The first is the story of his uncle, his younger brother, who had been at odds with his father his entire life.

My uncle, who believes that his family was ruined because of his 'red' brother, is so cold that he hangs up on me without answering the phone when I call to inform him of my brother's death.

My uncle, who had been a lifelong drinker, would sometimes come to my house and act up, saying things like, “Are you so great that you ruined the family?” (page 38).

Every time, my father did not fight back and remained silent without answering.

I'd rather my uncle not show up at the funeral.

Whether he will appear or not is a matter of interest to everyone gathered at the funeral, and readers also watch with interest and curiosity throughout the book.

Can my dead father and my living uncle reconcile?

The second is a story about the friends my father made in Gurye.

Their faces are so diverse and three-dimensional that just looking at them feels like watching a sitcom.

Mr. Park, a classmate of my father's from elementary school and owner of a watch shop.

He is my father's best friend, even though they are polar opposites, having spent his entire life as a soldier and a drill instructor.

The bickering between the two old men due to their differences in political orientation is somehow cute, and the line at the end, “Still, people should be the best” (page 47), makes me think that today’s political world should learn from it.

And a girl with bright yellow hair who appeared out of place at this funeral.

For some reason, he is said to be his father's "cigarette buddy" (page 139).

It is only possible for a father to become friendly with a seventeen-year-old girl, but the character of the father who does not forget to talk about 'American imperialism' to the girl whose mother is Vietnamese still makes people laugh.

In addition, many people who claim to be the father's sons, including 'Haksu', and the unfortunate stories of those who fought with guns but eventually became friends, appear one after another.

Is the father I knew real?

The countless episodes he left behind

The third is the story of 'me' and my father.

The main plot of ‘Father’s Liberation Diary’ is the process by which the daughter, who has lived a difficult life as the ‘daughter of a guerrilla,’ comes to understand her father.

Because he was a socialist and a revolutionary fighter, he had no ability to make a living, and because he did not hesitate to “guarantee” (page 57) for such a situation, the family’s poverty was always the fault of his father.

The long-winded stories my father would tell me without any warning were out of touch with reality, and that's why I wanted to leave my hometown where my father was.

But after my father's death, 'I' realized that the face of my father that I knew was only a small part of it.

The father's rational and realistic side is revealed, as well as his boldness that inspired people.

More than anything, I remember the moments when I loved myself, which I had forgotten.

Finally, 'I' hold my father's remains in my hands and decide to send him off in the most fatherly way possible.

The fourth and final one is anecdotes between mother and father.

They add a lively touch to the weight of the narrative and make readers laugh.

His mother, a lifelong comrade and also a socialist, was more realistic than his father.

So my father is always being bullied for one reason or another.

There are relatively minor things like not being able to quit drinking and smoking because you don't wash your clothes, and there are also major things like being forced to give up farming because you had to guarantee a loan.

In some ways, these people, who seem like enemies, become one in a devout manner in front of 'materialism' and 'nation', and this comical 'tiki-taka' becomes a pleasant catalyst for understanding the father's life.

"The Daughter of the Guerillas, the Daughter of Korean Literature"

The sensation called Jung Ji-ah

The appearance of Jeong Ji-ah 32 years ago was a sensation in Korean literature.

It was not because of a series of incidents such as the ban on sales and the prosecution by the public security authorities, but because of the vivid descriptions he showed and his serious attitude toward history.

Now, in addition to that attitude, Jeong Ji-ah has the composure to freely tell a story by mixing fact and fiction, and the appearance of a master who holds the reader's hand tightly until the last page.

This is precisely why I expect that Jeong Ji-ah will once again prove her presence with this novel, released after 32 years.

Everyone who loves Korean literature should listen to the words of novelist Kim Mi-wol, “Jeong Ji-ah is not only the daughter of a guerrilla, but also a precious daughter of our literature.”

Author's Note

When I returned to my hometown, I saw a world of beauty that I had never seen in Seoul.

The cherry blossom road along the Seomjin River, the sunset at Banyabong Peak, and the sea of clouds at Nogodan are not the only beautiful things.

The neighborhood old lady who says she really hates cherry blossoms and cornelian cherry blossoms, the restaurant owner who insists on bringing you food even though you don't need it, saying that you need to eat it to gain strength, the market old lady who lied and sold you tough vegetables that you couldn't eat by saying that they would become soft if you boiled them, and the restaurant owner who yelled at me to sit at the table furthest from the kitchen even though there was no one there (it turned out she had severe arthritis). This place is full of people who smell like people.

Why else would the old lady lie?

It's all about eating and living.

When in a hurry, isn't it human to lie and yell?

How can a person be so stubborn?

Father, it was number eighteen.

When I accept those words, the world becomes so beautiful.

I should have listened to my father a long time ago.

father.

Father, daughter, I have lived wrongly for so long.

Still, since I knew it before my sixtieth birthday, it's better than never knowing, right? I understand that you gave birth to me as a great man, and as a woman of humble character, so please forgive my past arrogance, rudeness, and foolishness... Thank you, Father.

I am saying this easy thing to a child now, just before my 60th birthday, after my father passed away.

What can I do? That's my father's daughter.

This ugly daughter dedicates this book to her father.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: September 2, 2022

- Page count, weight, size: 268 pages | 326g | 122*188*16mm

- ISBN13: 9788936438838

- ISBN10: 8936438832

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)