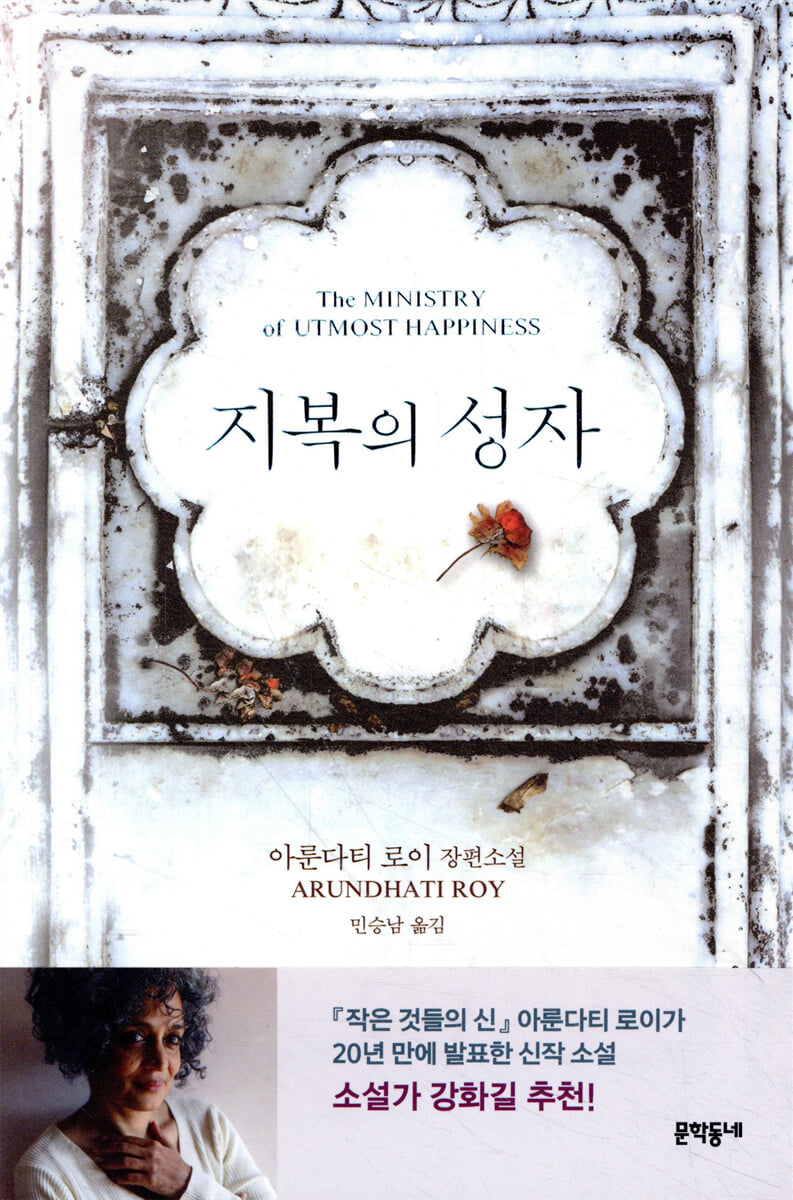

Saint of Bliss

|

Description

Book Introduction

Living in the shadow of reality and fading away as a stain of history A hymn to the most profane and sacred “When everything falls apart, the only ethical thing to do is to talk about it, write about it, act about it, sing about it.” _Arundhati Roy (from an interview with The Economic Times) Indian author Arundhati Roy, who received worldwide attention in 1997 when she won the Booker Prize for her debut novel, The God of Small Things, has published her new novel, The Saint of Bliss. This is his second novel, published in 20 years, after his first work, and after being active as a human rights and environmental activist, he has devoted his energy to socially engaged essays. As this was a new work released after a long silence as a novelist, the response from critics and readers was also enthusiastic. It became a bestseller upon publication, and following The God of Small Things, this work was also nominated for the Man Booker Prize. Set primarily in Delhi and Kashmir, India, this epic tale spans decades from the 1950s to the present, capturing life and death in all its forms and manifestations with poignant clarity. The author vividly depicts the harsh reality of India, where death has become a daily occurrence due to sharp conflicts between religions, classes, and factions, and especially the suffering of those who are oppressed and excluded without belonging anywhere, in powerful and flowing prose. However, the author's gaze toward his homeland suffering from division is not one of objectification toward others, but rather one of empathy and compassion, a thoroughly insider gaze, and thus harsh, yet pitiful and endearing. That gaze does not stop at the desolate land where countless lives are cruelly lost every day, but reaches deeper, deep into the gaping wounds, to where hope finally takes root. Arundhati Roy spent ten years writing The Blissful Saint. I waited silently, without rushing, until the world containing the seeds of a story approached, took root within me, paved the way, and gradually took shape. In this work, built through such a long period of reflection and with delicate and vibrant language, everything is alive. Not only people, plants and animals, but also objects and spaces. What is important is that this liveliness is not a simple literary technique, but the essence of the world the author pursues. The literature Roy pursues is not a flat landscape to be simply admired with the eyes, but a three-dimensional space that readers can experience by walking through it. The author says that in an age when factual truth is losing its power, only novels can show the true face of our society without lies. However, regarding the assessment that 『The Saint of Bliss』 is a political statement, he refuted it by saying, “Novels should deal with reality, but I did not write this novel to deal with reality; I just did not turn away from reality” (from an interview with [Vogue]). Of course, this work is based on real events, such as the reality of Kashmir, where conflict and civil war have continued since India gained independence from Britain, and the massacre of Muslims in Gujarat in 2002. However, such historical events are persuasive not because of the context outside the work, but because they function fully as the internal reality of the work in which the characters live. And only then, when a novel is complete as a novel, can literature create a rift in reality. As he did 20 years ago, Roy offers his poems of true mourning, love, and revolution to the world's small beings in a voice that only great literature can produce. |

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

1 .

Where do old birds go to die? _ 013

2 .

Quabga _ 018

3 .

Birth _ 131

4 .

Dr. Azad Bhartiya _ 170

5 .

Slow Goose Chase _ 182

6 .

Some Questions About the Future _ 188

7 .

Landlord _ 191

8 .

Tenant _ 285

9 .

The Untimely Death of Miss Jevin I _ 409

10 .

The Saint of Bliss _ 521

11 .

Landlord _ 560

12 .

Ear Kiyom _ 569

Acknowledgments _ 575

Translator's Note: Paradise Cemetery of the Hijra _ 581

Where do old birds go to die? _ 013

2 .

Quabga _ 018

3 .

Birth _ 131

4 .

Dr. Azad Bhartiya _ 170

5 .

Slow Goose Chase _ 182

6 .

Some Questions About the Future _ 188

7 .

Landlord _ 191

8 .

Tenant _ 285

9 .

The Untimely Death of Miss Jevin I _ 409

10 .

The Saint of Bliss _ 521

11 .

Landlord _ 560

12 .

Ear Kiyom _ 569

Acknowledgments _ 575

Translator's Note: Paradise Cemetery of the Hijra _ 581

Detailed image

Into the book

Where do old birds go to die? Do they fall like stones from the sky onto our heads? Do we stumble upon bird carcasses in the streets? Has the omnipotent being who placed us on this earth provided a suitable means of taking us away?

--- pp.16-17

The important thing was that it existed.

Even a mere giggle in history was a world apart from absence, from being completely omitted.

Because that giggle ended up being a stepping stone to climb the steep cliff called the future.

--- p.76

He believed that he was always right.

She believed that she was completely, always wrong.

He was reduced to his own certainty.

She was enlarged by her own ambiguity.

--- p.166

In our world, normality is a bit like a boiled egg.

In that the yolk of a terribly violent egg is contained within the center of that monotonous shell.

For complex and diverse people like us to continue to coexist? For us to continue to live together, tolerate each other, and occasionally kill each other? The rules we establish are based on our constant anxiety about violence, the memory of its past actions, and the fear of its future manifestation.

As long as the center doesn't shake, as long as the yolk doesn't leak out, we'll be fine.

--- p.201

Practicing for a performance that will ultimately never come to fruition—isn't that what life is all about? Or isn't that how most lives end?

--- p.202

The moment I first saw her, a part of me walked out of my body and surrounded her.

And it still remains that way.

--- p.203

We do terrible things to each other.

They hurt each other, betray each other, and kill each other.

But we understand each other.

--- p.258

Who can know what kind of farewell awaits us when we say goodbye?

--- p.341

It seems hopeless.

But pretending to be hopeful is the only dignity we have… …

--- p.356

There was death everywhere.

Death was everything.

personal history.

craving.

dream.

city.

love.

Youth itself.

Death became another way of living.

--- p.415

This is all I know for sure.

In our Kashmir, the dead live forever, and the living are just dead people pretending to be alive.

--- p.452

“You can’t win this fight with just your body.

“Our souls must be conscripted as well.”

--- p.487

How do I tell this shattered story? Slowly, by becoming everyone.

no.

Slowly everything becomes one.

--- pp.16-17

The important thing was that it existed.

Even a mere giggle in history was a world apart from absence, from being completely omitted.

Because that giggle ended up being a stepping stone to climb the steep cliff called the future.

--- p.76

He believed that he was always right.

She believed that she was completely, always wrong.

He was reduced to his own certainty.

She was enlarged by her own ambiguity.

--- p.166

In our world, normality is a bit like a boiled egg.

In that the yolk of a terribly violent egg is contained within the center of that monotonous shell.

For complex and diverse people like us to continue to coexist? For us to continue to live together, tolerate each other, and occasionally kill each other? The rules we establish are based on our constant anxiety about violence, the memory of its past actions, and the fear of its future manifestation.

As long as the center doesn't shake, as long as the yolk doesn't leak out, we'll be fine.

--- p.201

Practicing for a performance that will ultimately never come to fruition—isn't that what life is all about? Or isn't that how most lives end?

--- p.202

The moment I first saw her, a part of me walked out of my body and surrounded her.

And it still remains that way.

--- p.203

We do terrible things to each other.

They hurt each other, betray each other, and kill each other.

But we understand each other.

--- p.258

Who can know what kind of farewell awaits us when we say goodbye?

--- p.341

It seems hopeless.

But pretending to be hopeful is the only dignity we have… …

--- p.356

There was death everywhere.

Death was everything.

personal history.

craving.

dream.

city.

love.

Youth itself.

Death became another way of living.

--- p.415

This is all I know for sure.

In our Kashmir, the dead live forever, and the living are just dead people pretending to be alive.

--- p.452

“You can’t win this fight with just your body.

“Our souls must be conscripted as well.”

--- p.487

How do I tell this shattered story? Slowly, by becoming everyone.

no.

Slowly everything becomes one.

--- pp.570-571

Publisher's Review

A paradise for those who cannot be defined and therefore do not exist,

In that place guarded by neither man nor woman

A lost woman comes to visit.

Holding a small life born from despair but that will eventually grow into hope.

The novel is largely divided into two stories, and at the center of one of them is a character named 'Anjum'.

Anjum was born in the mid-1950s in Delhi, India, with both male and female genitalia.

Anjum's parents are desperate and try to raise their child as a man, but Anjum happens to see a 'hijra' (a third gender who does not fit the conventional male or female gender) walking freely in the market dressed in women's clothing and feels that she wants to be like that person.

Anjum, who identifies as a woman, eventually leaves her family and goes to live in a communal area called the Khwabgah, where hijras live together.

Now her new wish is to become a mother.

Then, his dream becomes reality when he finds a girl crying alone, abandoned on the temple steps.

Anjum brings the child to Khwabgah, names her Zainab, and showers her with utmost love.

Then one day, Anjum goes to a temple in another region to pray for the health of Zainab, who is suffering from various illnesses for no reason, and ends up passing through Gujarat, where he gets caught up in an indiscriminate lynching by a Hindu mob targeting Muslims.

Anjum, who was spared because killing a hijra was said to bring bad luck, returns in shock.

The trauma left by the incident prevents her from returning to her previous life and she eventually leaves Khwabga, taking refuge in the village's shabby cemetery.

Anjum's family and unidentified people of lower class are buried there.

Anjum builds a small, shabby house there and begins to live there.

Anjum, who gradually regained her strength in her new home, gradually expanded her residence and built a guesthouse for the poor and homeless, naming it 'Jannat', or Paradise.

And after a while, he started another business with a larger family.

It is the act of burying a body that no one else will accept with a simple funeral.

Thus, the new nest built by Anjum becomes a strange sanctuary where the poor and the marginalized can entrust both life and death.

The central characters who play another role in the story are four friends of the same age: Tilo, Musa, Biplop, and Naga.

They first met at university in the mid-1980s.

Biplop and Naga are from wealthy upper-class families and have known each other since childhood.

At the time, they were graduate students in the Department of History, and they met Tilo, an architecture student, at a play rehearsal.

By Tilo's side is Musa, a taciturn young man who sticks to him like a lover or a brother.

She feels love for Tilo, who has a secret past and an unusual lifestyle, but is unable to express it properly and loses contact after graduation.

As time passes, Biplab becomes a high-ranking official in the Indian Intelligence Service and later a famous newspaper reporter.

Biplab, who was posted to Kashmir and working, receives a phone call one night.

After killing a vicious Islamic fighter, he captured a suspicious woman who was with him and asked her to deliver a message to Biplab: 'Garson Hobart.'

'Garson Hobart' was the name of a character Biplop played in a college play, and as soon as he heard the message, he recognized the captured woman as Tilo.

However, Biplab, who was unable to move immediately for security reasons, sent Naga, who was working as a correspondent in Kashmir, to bring her back safely.

Some time after that, Tilo marries Naga.

More than a decade later, the two stories finally converge on a busy street.

An abandoned newborn baby is found in a Delhi square, always filled with protesters.

As time passes and the parents do not show up, people suggest handing the baby over to the police.

But then, out of nowhere, a man appears, furious as hell, and says he will take the child away.

This is Anjum, who came out to watch the protest.

A scuffle breaks out between those who insist on handing the baby over to the police and Anjum, and in the confusion, the baby disappears.

It was Tilo who took the baby, and she accepted this little life that had arrived before her on the mysterious current of life as her fate.

What she didn't know was that riding that mysterious current of life, more family and a true home were coming her way.

A community of life and death bound only by love

Hazrat Sarmad, the title of the novel and referred to as the 'Saint of Bliss' in the work, is a saint from Persia.

After coming to Delhi, India, in search of the love of his life, he abandoned Judaism, embraced Islam, and fell in love with a Hindu boy.

However, when the emperor ordered him to recite the Islamic creed that Allah is the only god, he insisted that he could not testify until he had completed his spiritual pursuit and could truly accept Allah.

In the end, he was executed for not bending his convictions to the end, and even after his head was cut off, love poems flowed from his mouth instead of his confession of faith.

Thus, Sarmad became a saint who cared for those who were comforted and who belonged nowhere.

“How do I tell this shattered story? Slowly, by becoming everyone.

no.

“Slowly everything becomes.” _Main text, pp. 570-571

The religious tolerance and boundless love symbolized by Sarmad are in line with the value of diversity that lies at the core of the novel.

The author argues that the diversity of Indian society, with its diverse languages, religions, and lifestyles, is not a chaos to be overcome and organized, but rather a liberating value that makes life more colorful and free.

In that sense, the Anjum community, bound together solely by mutual understanding and love, transcending secular boundaries such as gender, caste, and religion, is a place where the values of Sarmad are fully realized.

And in that it embraces countless branches of life and the stories contained within each, 『The Saint of Bliss』 also resembles Anjum's Paradise.

Even in the face of death, the author, with the heart of Sarmad, sings a poem of love rather than a prayer of rejection, and sheds an equal light on every corner of the vast world he has created.

At that moment, countless fragments of life flicker toward the reader as waves of infinite colors, each with its own unique character.

At that time, the novel is not just a story, but everyone, or rather, everything.

In that place guarded by neither man nor woman

A lost woman comes to visit.

Holding a small life born from despair but that will eventually grow into hope.

The novel is largely divided into two stories, and at the center of one of them is a character named 'Anjum'.

Anjum was born in the mid-1950s in Delhi, India, with both male and female genitalia.

Anjum's parents are desperate and try to raise their child as a man, but Anjum happens to see a 'hijra' (a third gender who does not fit the conventional male or female gender) walking freely in the market dressed in women's clothing and feels that she wants to be like that person.

Anjum, who identifies as a woman, eventually leaves her family and goes to live in a communal area called the Khwabgah, where hijras live together.

Now her new wish is to become a mother.

Then, his dream becomes reality when he finds a girl crying alone, abandoned on the temple steps.

Anjum brings the child to Khwabgah, names her Zainab, and showers her with utmost love.

Then one day, Anjum goes to a temple in another region to pray for the health of Zainab, who is suffering from various illnesses for no reason, and ends up passing through Gujarat, where he gets caught up in an indiscriminate lynching by a Hindu mob targeting Muslims.

Anjum, who was spared because killing a hijra was said to bring bad luck, returns in shock.

The trauma left by the incident prevents her from returning to her previous life and she eventually leaves Khwabga, taking refuge in the village's shabby cemetery.

Anjum's family and unidentified people of lower class are buried there.

Anjum builds a small, shabby house there and begins to live there.

Anjum, who gradually regained her strength in her new home, gradually expanded her residence and built a guesthouse for the poor and homeless, naming it 'Jannat', or Paradise.

And after a while, he started another business with a larger family.

It is the act of burying a body that no one else will accept with a simple funeral.

Thus, the new nest built by Anjum becomes a strange sanctuary where the poor and the marginalized can entrust both life and death.

The central characters who play another role in the story are four friends of the same age: Tilo, Musa, Biplop, and Naga.

They first met at university in the mid-1980s.

Biplop and Naga are from wealthy upper-class families and have known each other since childhood.

At the time, they were graduate students in the Department of History, and they met Tilo, an architecture student, at a play rehearsal.

By Tilo's side is Musa, a taciturn young man who sticks to him like a lover or a brother.

She feels love for Tilo, who has a secret past and an unusual lifestyle, but is unable to express it properly and loses contact after graduation.

As time passes, Biplab becomes a high-ranking official in the Indian Intelligence Service and later a famous newspaper reporter.

Biplab, who was posted to Kashmir and working, receives a phone call one night.

After killing a vicious Islamic fighter, he captured a suspicious woman who was with him and asked her to deliver a message to Biplab: 'Garson Hobart.'

'Garson Hobart' was the name of a character Biplop played in a college play, and as soon as he heard the message, he recognized the captured woman as Tilo.

However, Biplab, who was unable to move immediately for security reasons, sent Naga, who was working as a correspondent in Kashmir, to bring her back safely.

Some time after that, Tilo marries Naga.

More than a decade later, the two stories finally converge on a busy street.

An abandoned newborn baby is found in a Delhi square, always filled with protesters.

As time passes and the parents do not show up, people suggest handing the baby over to the police.

But then, out of nowhere, a man appears, furious as hell, and says he will take the child away.

This is Anjum, who came out to watch the protest.

A scuffle breaks out between those who insist on handing the baby over to the police and Anjum, and in the confusion, the baby disappears.

It was Tilo who took the baby, and she accepted this little life that had arrived before her on the mysterious current of life as her fate.

What she didn't know was that riding that mysterious current of life, more family and a true home were coming her way.

A community of life and death bound only by love

Hazrat Sarmad, the title of the novel and referred to as the 'Saint of Bliss' in the work, is a saint from Persia.

After coming to Delhi, India, in search of the love of his life, he abandoned Judaism, embraced Islam, and fell in love with a Hindu boy.

However, when the emperor ordered him to recite the Islamic creed that Allah is the only god, he insisted that he could not testify until he had completed his spiritual pursuit and could truly accept Allah.

In the end, he was executed for not bending his convictions to the end, and even after his head was cut off, love poems flowed from his mouth instead of his confession of faith.

Thus, Sarmad became a saint who cared for those who were comforted and who belonged nowhere.

“How do I tell this shattered story? Slowly, by becoming everyone.

no.

“Slowly everything becomes.” _Main text, pp. 570-571

The religious tolerance and boundless love symbolized by Sarmad are in line with the value of diversity that lies at the core of the novel.

The author argues that the diversity of Indian society, with its diverse languages, religions, and lifestyles, is not a chaos to be overcome and organized, but rather a liberating value that makes life more colorful and free.

In that sense, the Anjum community, bound together solely by mutual understanding and love, transcending secular boundaries such as gender, caste, and religion, is a place where the values of Sarmad are fully realized.

And in that it embraces countless branches of life and the stories contained within each, 『The Saint of Bliss』 also resembles Anjum's Paradise.

Even in the face of death, the author, with the heart of Sarmad, sings a poem of love rather than a prayer of rejection, and sheds an equal light on every corner of the vast world he has created.

At that moment, countless fragments of life flicker toward the reader as waves of infinite colors, each with its own unique character.

At that time, the novel is not just a story, but everyone, or rather, everything.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: February 3, 2020

- Page count, weight, size: 588 pages | 728g | 140*210*30mm

- ISBN13: 9788954670241

- ISBN10: 8954670245

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)