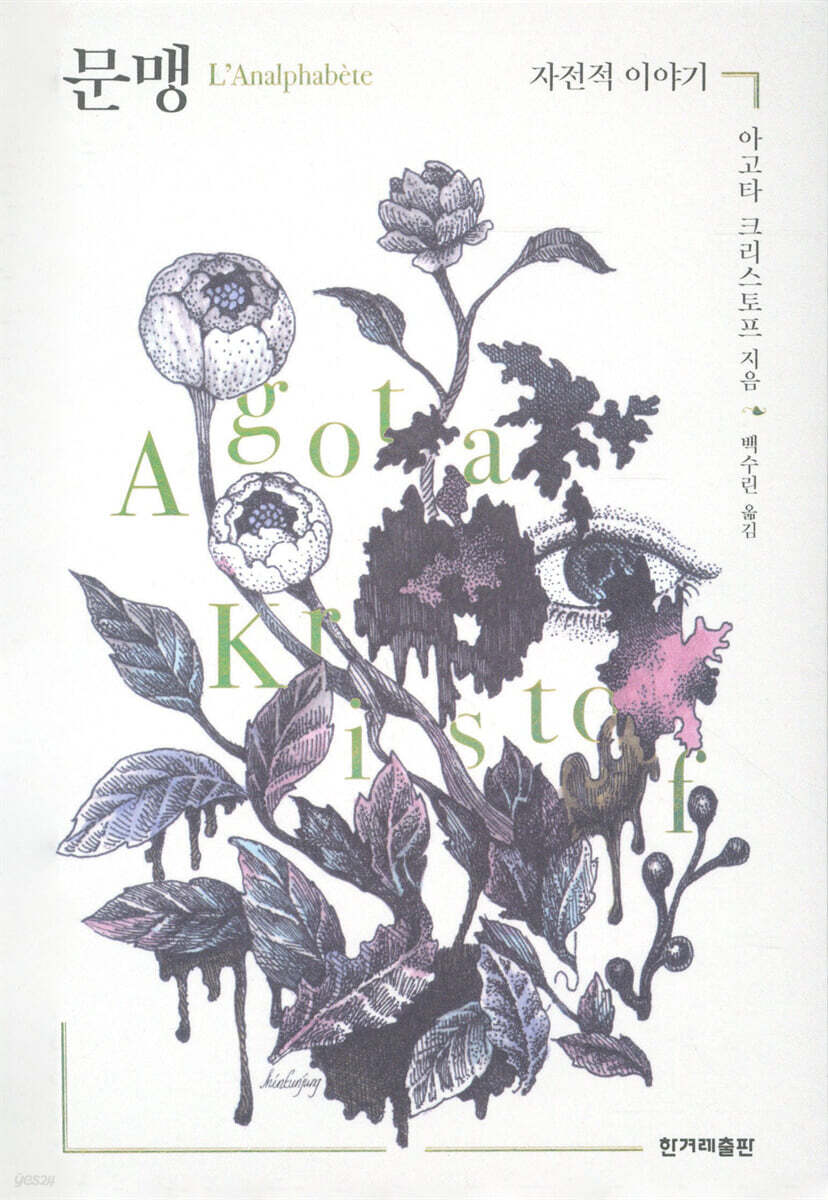

illiteracy

|

Description

Book Introduction

- A word from MD

- From his childhood suffering from the "incurable disease of reading" to his time in exile, when he lost his native language and became illiterate, to learning French and writing novels.

A story of will and courage that never wavered as a 'woman' and 'foreigner' who had to endure the painful history of the 20th century.

- Literature MD Kim Do-hoon

Until the existence of 『The Three Lies of Existence』

Agotha Kristof's autobiographical story

"Illiteracy" is an autobiographical story about the linguistic identity of Agota Kristof, a Hungarian female writer who has earned the respect of numerous luminaries, including philosopher Slavoj Zizek, novelists Kim Yeon-su, Eun Hee-kyung, and Jeong I-hyeon, and writer Lee Dong-jin, for depicting the uncertainty and absurdity of human society in remarkably calm and dry sentences.

It was published by the Swiss publisher Zoe in 2004, about 12 years after the trilogy novel The Three Lies of Existence, which is a classic of modern French literature and has been translated into over 40 languages and called a "quiet bestseller."

This book records her life from the time she began reading at the age of four and was obsessed with reading and stories to the point of being pathological, to the time when she lost her native language and became illiterate after being exiled to Switzerland, and to the time when she learned French again and wrote her first novel, “Secret Note,” the first part of “The Three Lies of Existence.”

"Illiteracy" is a record of the quiet struggle during the time when one had to learn the "enemy language" of "French" that "murdered" one's native language, Hungarian, and threatened one's identity as a Hungarian. It is also a record of creation that confirms the novelistic origins of the harsh and cruel scenes of "The Three Lies of Existence" and the image of boys who discipline themselves harshly and have no morality, and is an "autobiography of language" filled with the agony and longing for "reading" and "writing."

Through "Illiteracy," she revives the intimate memories she lost along with her native Hungarian language in eleven chapters, and reveals the will and courage that never sank as a "woman" and a "foreigner" who had to endure the history of the 20th century.

It is introduced in Korea for the first time through a translation by novelist Baek Su-rin.

Agotha Kristof's autobiographical story

"Illiteracy" is an autobiographical story about the linguistic identity of Agota Kristof, a Hungarian female writer who has earned the respect of numerous luminaries, including philosopher Slavoj Zizek, novelists Kim Yeon-su, Eun Hee-kyung, and Jeong I-hyeon, and writer Lee Dong-jin, for depicting the uncertainty and absurdity of human society in remarkably calm and dry sentences.

It was published by the Swiss publisher Zoe in 2004, about 12 years after the trilogy novel The Three Lies of Existence, which is a classic of modern French literature and has been translated into over 40 languages and called a "quiet bestseller."

This book records her life from the time she began reading at the age of four and was obsessed with reading and stories to the point of being pathological, to the time when she lost her native language and became illiterate after being exiled to Switzerland, and to the time when she learned French again and wrote her first novel, “Secret Note,” the first part of “The Three Lies of Existence.”

"Illiteracy" is a record of the quiet struggle during the time when one had to learn the "enemy language" of "French" that "murdered" one's native language, Hungarian, and threatened one's identity as a Hungarian. It is also a record of creation that confirms the novelistic origins of the harsh and cruel scenes of "The Three Lies of Existence" and the image of boys who discipline themselves harshly and have no morality, and is an "autobiography of language" filled with the agony and longing for "reading" and "writing."

Through "Illiteracy," she revives the intimate memories she lost along with her native Hungarian language in eleven chapters, and reveals the will and courage that never sank as a "woman" and a "foreigner" who had to endure the history of the 20th century.

It is introduced in Korea for the first time through a translation by novelist Baek Su-rin.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

start

From speech to writing

city

Foolishness

Mother tongue and enemy language

Stalin's death

memory

People who are out of place

desert

How do we become writers?

illiteracy

Translator's Note

From speech to writing

city

Foolishness

Mother tongue and enemy language

Stalin's death

memory

People who are out of place

desert

How do we become writers?

illiteracy

Translator's Note

Into the book

“We walk through the forest.

for a long time.

overlong.

Branches scratch our faces, we fall into holes, leaves soak our shoes, and we trip on roots and twist our ankles.

Even if I turn on the portable lamp, it only lights up a small circle, the trees, the trees that still go on.

But we should have already gotten out of the forest.

“We feel like we’re constantly going around in circles.” --- p.70

“I wake up at 5:30.

I feed and dress the baby, then dress myself and go to catch the 6:30 bus that takes me to the factory.

I leave my child at daycare and go to work at the factory.

I leave the factory at 5pm.

I pick up my daughter from daycare, get back on the bus, and head home.

“I do some shopping at the small shop in town, light a fire (there is no central heating in the apartment), prepare dinner, put the kids to bed, do the dishes, write a little, and then I go to sleep.” --- p.87~88

“We become writers.

“We write persistently and stubbornly, never losing faith in what we write.”

for a long time.

overlong.

Branches scratch our faces, we fall into holes, leaves soak our shoes, and we trip on roots and twist our ankles.

Even if I turn on the portable lamp, it only lights up a small circle, the trees, the trees that still go on.

But we should have already gotten out of the forest.

“We feel like we’re constantly going around in circles.” --- p.70

“I wake up at 5:30.

I feed and dress the baby, then dress myself and go to catch the 6:30 bus that takes me to the factory.

I leave my child at daycare and go to work at the factory.

I leave the factory at 5pm.

I pick up my daughter from daycare, get back on the bus, and head home.

“I do some shopping at the small shop in town, light a fire (there is no central heating in the apartment), prepare dinner, put the kids to bed, do the dishes, write a little, and then I go to sleep.” --- p.87~88

“We become writers.

“We write persistently and stubbornly, never losing faith in what we write.”

--- p.103

Publisher's Review

The challenge of an illiterate person

Agota Kristof was born in a rural Hungarian village in 1935 and lived through the wartime years of World War II, witnessing her homeland being invaded by both Germany and the Soviet Union.

Her impoverished childhood with her older brother and younger brother in a border town where many languages intersected had a profound influence on her later writing. One of the twins in The Three Lies of Existence, Lucas, is herself, and the other, Klaus, is modeled after her brother, and the town where she lived then becomes the setting for the novel.

Married at nineteen and a mother at twenty-one, she fled Hungary in 1956 to escape the aftermath of the Hungarian Revolution, taking her anti-government husband and four-month-old daughter with her, moving via Austria to Neuchâtel in Switzerland.

In utter loneliness, with no friends or relatives, she worked more than ten hours a day in a watch factory to make a living, but her thirst for writing led her to publish her poems in the Hungarian Literature.

Until then, her writing style, which had been sentimental poetry in Hungarian, gradually developed into the present style, which is simple, transparent, and free of embellishments, as she wrote plays and novels in French, a new language.

In 1987, he published "Secret Note," the first part of "The Three Lies of Existence" and his first novel, and over the next five years he completed the second part, "The Evidence of Others," and the third part, "Fifty Years of Solitude."

In 『Illiteracy』, a series of anecdotes are introduced, including the story of how she sent the manuscript of "The Secret Notebook" to Gallimard, Seyoul, and Grasse, received a rejection letter, and was contacted by an editor before it was finally published.

This trilogy was a huge success worldwide, and was also introduced in Korea under the title “The Three Lies of Existence”, where it became a steady seller.

Since then, she has published several novels and plays, winning awards including the Prix Libre Inter in 1992, the Gottfried Keller Prize in 2001, the Schiller Prize in 2005, the Austrian European Literature Prize in 2008, and the Koschut Prize in 2011.

He died in Neuchâtel in July 2011 at the age of seventy-five.

From her childhood to her adolescence, and until she gets married and leaves Hungary, moving to Austria and then Switzerland, she experiences constant loss of 'language' and learning of 'language'.

In "Illiteracy," she shows how she has persistently written to overcome 'illiteracy,' but she also makes it clear that she will never be able to escape 'illiteracy.'

“I have been speaking French for over 30 years, and writing for over 20, and yet I still do not know the language.

“I make mistakes when speaking French, and I have to frequently use dictionaries to write in French.” _pp. 52-53

But this is not the entire reason why the book is titled “Illiteracy.”

The real reason the book is titled 'Illiteracy' is because she says that she will not be discouraged by the forced and unfair circumstances and will continue to write as an 'illiterate' person.

“I know from birth that I will never be able to write in French like the writers who speak French.

But I will write as best I can, as best I can.” _Page 112

“Writing in French is something that is forced on me.

This is a challenge.

“The Challenge of an Illiterate Man.” _Page 113

As she answered the question, 'How do we become writers?'

“We become writers.

“We write persistently and stubbornly, never losing faith in what we write.” _Page 103

Between someone's native language and my native language

A flowing translation by novelist Baek Su-rin

Novelist Baek Su-rin, who translated "Illiteracy," is very similar to Agota Kristof in that she suffered from the disease of reading at a very young age, fell in love with writing at some point, and experienced being a foreigner outside her native language and country.

Furthermore, her past records, in which she has consistently expressed her experiences as a foreigner through writing, such as “Falling in Paul,” the story of “I,” a Korean language instructor, and “Paul,” a Korean-American student; “The Tree with Crows,” the story of Lee, a construction company employee dispatched to Africa; and “Practice Lying,” the story of me running away to study abroad in France, show that she is perfectly suited to translate “Illiteracy.”

As a reader and a novelist, as someone who has long been around those who seriously study foreign literature and as someone who translates one language into another, she is sometimes a "stranger" and sometimes an "illiterate," guessing, rewriting, and rereading between fear and liberation, helping this book reach someone whose native language is not French.

Translator's Note

If someone were to ask me what was the most memorable part of "Illiteracy," I would choose the part where Agota Christophe wanders through the forest under the guidance of a menstrual guide.

This is because the author wrote that he was carrying two bags at the time, one containing the baby's diapers and changes of clothes, and the other containing a dictionary.

It is significant that Agotha Kristoff, who packed her bags repeatedly, putting in and taking out various items, had a dictionary in her bag as she turned her back on her country and family.

The dictionary – perhaps a bilingual one in German and Hungarian – was a conduit between her native language and a foreign language, a symbol of at least something that allowed her to preserve her language (her identity) in a foreign country.

_Baek Su-rin

Agota Kristof was born in a rural Hungarian village in 1935 and lived through the wartime years of World War II, witnessing her homeland being invaded by both Germany and the Soviet Union.

Her impoverished childhood with her older brother and younger brother in a border town where many languages intersected had a profound influence on her later writing. One of the twins in The Three Lies of Existence, Lucas, is herself, and the other, Klaus, is modeled after her brother, and the town where she lived then becomes the setting for the novel.

Married at nineteen and a mother at twenty-one, she fled Hungary in 1956 to escape the aftermath of the Hungarian Revolution, taking her anti-government husband and four-month-old daughter with her, moving via Austria to Neuchâtel in Switzerland.

In utter loneliness, with no friends or relatives, she worked more than ten hours a day in a watch factory to make a living, but her thirst for writing led her to publish her poems in the Hungarian Literature.

Until then, her writing style, which had been sentimental poetry in Hungarian, gradually developed into the present style, which is simple, transparent, and free of embellishments, as she wrote plays and novels in French, a new language.

In 1987, he published "Secret Note," the first part of "The Three Lies of Existence" and his first novel, and over the next five years he completed the second part, "The Evidence of Others," and the third part, "Fifty Years of Solitude."

In 『Illiteracy』, a series of anecdotes are introduced, including the story of how she sent the manuscript of "The Secret Notebook" to Gallimard, Seyoul, and Grasse, received a rejection letter, and was contacted by an editor before it was finally published.

This trilogy was a huge success worldwide, and was also introduced in Korea under the title “The Three Lies of Existence”, where it became a steady seller.

Since then, she has published several novels and plays, winning awards including the Prix Libre Inter in 1992, the Gottfried Keller Prize in 2001, the Schiller Prize in 2005, the Austrian European Literature Prize in 2008, and the Koschut Prize in 2011.

He died in Neuchâtel in July 2011 at the age of seventy-five.

From her childhood to her adolescence, and until she gets married and leaves Hungary, moving to Austria and then Switzerland, she experiences constant loss of 'language' and learning of 'language'.

In "Illiteracy," she shows how she has persistently written to overcome 'illiteracy,' but she also makes it clear that she will never be able to escape 'illiteracy.'

“I have been speaking French for over 30 years, and writing for over 20, and yet I still do not know the language.

“I make mistakes when speaking French, and I have to frequently use dictionaries to write in French.” _pp. 52-53

But this is not the entire reason why the book is titled “Illiteracy.”

The real reason the book is titled 'Illiteracy' is because she says that she will not be discouraged by the forced and unfair circumstances and will continue to write as an 'illiterate' person.

“I know from birth that I will never be able to write in French like the writers who speak French.

But I will write as best I can, as best I can.” _Page 112

“Writing in French is something that is forced on me.

This is a challenge.

“The Challenge of an Illiterate Man.” _Page 113

As she answered the question, 'How do we become writers?'

“We become writers.

“We write persistently and stubbornly, never losing faith in what we write.” _Page 103

Between someone's native language and my native language

A flowing translation by novelist Baek Su-rin

Novelist Baek Su-rin, who translated "Illiteracy," is very similar to Agota Kristof in that she suffered from the disease of reading at a very young age, fell in love with writing at some point, and experienced being a foreigner outside her native language and country.

Furthermore, her past records, in which she has consistently expressed her experiences as a foreigner through writing, such as “Falling in Paul,” the story of “I,” a Korean language instructor, and “Paul,” a Korean-American student; “The Tree with Crows,” the story of Lee, a construction company employee dispatched to Africa; and “Practice Lying,” the story of me running away to study abroad in France, show that she is perfectly suited to translate “Illiteracy.”

As a reader and a novelist, as someone who has long been around those who seriously study foreign literature and as someone who translates one language into another, she is sometimes a "stranger" and sometimes an "illiterate," guessing, rewriting, and rereading between fear and liberation, helping this book reach someone whose native language is not French.

Translator's Note

If someone were to ask me what was the most memorable part of "Illiteracy," I would choose the part where Agota Christophe wanders through the forest under the guidance of a menstrual guide.

This is because the author wrote that he was carrying two bags at the time, one containing the baby's diapers and changes of clothes, and the other containing a dictionary.

It is significant that Agotha Kristoff, who packed her bags repeatedly, putting in and taking out various items, had a dictionary in her bag as she turned her back on her country and family.

The dictionary – perhaps a bilingual one in German and Hungarian – was a conduit between her native language and a foreign language, a symbol of at least something that allowed her to preserve her language (her identity) in a foreign country.

_Baek Su-rin

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: May 9, 2018

- Format: Hardcover book binding method guide

- Page count, weight, size: 128 pages | 212g | 124*182*20mm

- ISBN13: 9791160401608

- ISBN10: 1160401608

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)