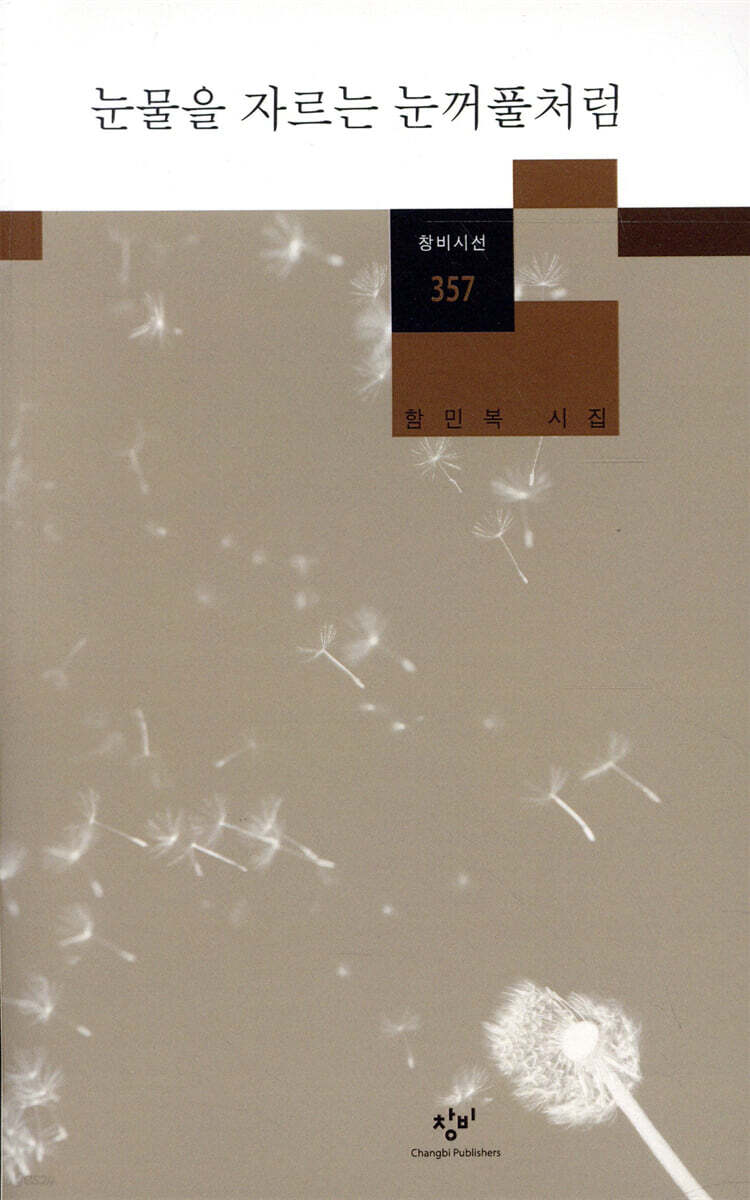

Like an eyelid that cuts off tears

|

Description

Book Introduction

Poet Ham Min-bok's poetry, which writes in humble language about life, objects, tools, and the earth, "translates humanity and the world," to borrow his own words.

Through his poetry, our lives, society, and civilization acquire new meaning.

Everything that is visible, as well as the invisible, the things we try not to see, find their breath in his poetry.

So his poetic imagination sets the reader ablaze, makes him imagine, and ultimately changes him.

His new poetry collection, “Like Eyelids That Cut Tears,” is his fifth collection of poetry in eight years.

The weight of time contained in each of his slow, steady steps is expressed in 70 lines.

The poet's language, longing for a good heart, displays a much softer lyrical power in this new poetry collection after a long time.

His poetry, which allows us to feel the leisurely spark of hope even in a life of poverty, is an extension of his past work that sang of the lives of the poor marginalized in a capitalist society, but it evokes a much warmer sympathy.

The poet's thoughts on pursuing an equal life linger on the objects around us that have lost their function and suddenly make us realize the shabbiness of life, such as a tape measure that is "wound up and measuring my body" ("Measure Measure"), a broken clock that is heavier "than when it was alive and moving" ("Dead Clock"), and a scale that has rusted and been abandoned ("Crunchy Scale").

But this does not reach the point of making the difficult daily life even heavier, because it quietly unravels these poor scenes, subtly showing the tenacious and determined side of all the directors.

The poet's records, which do not take a single moment lightly, approach all beings in the world with a heartfelt and unadorned testimony.

His poetry is warm yet poor because it has the positive power to raise up poverty.

His poem, which hopes to “shake so as not to be shaken/sway so as not to be shaken/stretch out branches and sprout leaves” (“Shaking”), will be a warm comfort to all those who dream of a better life, a better society, and a world different from the present.

Through his poetry, our lives, society, and civilization acquire new meaning.

Everything that is visible, as well as the invisible, the things we try not to see, find their breath in his poetry.

So his poetic imagination sets the reader ablaze, makes him imagine, and ultimately changes him.

His new poetry collection, “Like Eyelids That Cut Tears,” is his fifth collection of poetry in eight years.

The weight of time contained in each of his slow, steady steps is expressed in 70 lines.

The poet's language, longing for a good heart, displays a much softer lyrical power in this new poetry collection after a long time.

His poetry, which allows us to feel the leisurely spark of hope even in a life of poverty, is an extension of his past work that sang of the lives of the poor marginalized in a capitalist society, but it evokes a much warmer sympathy.

The poet's thoughts on pursuing an equal life linger on the objects around us that have lost their function and suddenly make us realize the shabbiness of life, such as a tape measure that is "wound up and measuring my body" ("Measure Measure"), a broken clock that is heavier "than when it was alive and moving" ("Dead Clock"), and a scale that has rusted and been abandoned ("Crunchy Scale").

But this does not reach the point of making the difficult daily life even heavier, because it quietly unravels these poor scenes, subtly showing the tenacious and determined side of all the directors.

The poet's records, which do not take a single moment lightly, approach all beings in the world with a heartfelt and unadorned testimony.

His poetry is warm yet poor because it has the positive power to raise up poverty.

His poem, which hopes to “shake so as not to be shaken/sway so as not to be shaken/stretch out branches and sprout leaves” (“Shaking”), will be a warm comfort to all those who dream of a better life, a better society, and a world different from the present.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

Publisher's Review

Tears as warm as spring rain, a song for all pain and hope.

Poet Ham Min-bok, who has sung about the lives of the poor and marginalized in capitalist society with the power of 'innate longing' that springs from a good heart, has published a new poetry collection, 'Like an Eyelid That Cuts Tears.'

This is the fifth poetry collection, published eight years after the fourth poetry collection, “Soft Power” (Munhaksegyesa), published in 2005, ten years later.

Although it is a rather slow pace compared to the current poetry landscape, it contains 70 masterpieces that are worthy of the weight of time, enough to justify the comment that “Ham Min-bok’s imagination is social capital that we should be willing to share” (Lee Moon-jae, recommendation).

In this collection of poems, where the power of gentle lyricism stands out, the poet unfolds a philosophy of life imbued with the leisure to keep the spark of hope alive even in poverty, and a worldview of “existential thinking derived from experience” (Moon Hye-won, commentary) that dreams of a world where we live together with others.

The poems, written with the honest and plain 'voice of life' contained in refined language, without hasty rhetoric or exaggeration that plays at the fingertips, evoke warm empathy and leave a gentle resonance.

When I look at the full moon, my heart quickly becomes round/When I listen to the waning moon, my heart becomes hollow//The moon is/the whetstone of the heart//It brightly and sadly rules the sharp heart//The moon//The shadow I have encountered/is the mirror with the deepest lyricism (Full text from “Moon”)

The poet's thoughts on living an equal life with others are naturally revealed in life.

Interestingly, the poet focuses on objects that have lost their original function, such as a tape measure that is “wound up and measuring my body” (“Measurement Tape”), a broken clock that is heavier “than when it was alive” (“Dead Clock”), and a rusted, abandoned scale (“Crunchy Scale”), and obtains the basis for ontological thinking from them.

Here, the poet reads the shining objecthood of discarded objects with a fog-like vision that “erases the landscape/drawing the landscape” and “erases the building/drawing the time when there was no building,” and perceives the inherent nature of objects that have been “liberated from the world of appearance” (“Fog”).

I add to myself and subtract from myself/I read you//I lean towards you and then towards myself, waiting to be able to read myself through you//Focus on the other person, in the end, balance,/There is no actual burden thrown, but the burdens are lightened by each other (from the “scales”)

The reality of struggling to carry on with the arduous daily routine has long since become a sorrow felt by countless people living in this era, regardless of generation or class.

The poet also knows better than anyone the misery of such a life.

As he calmly unfolds the scenes of this shabby life, he subtly reveals the tenacious and determined side of all the directors.

The fish heads on the stalls/are all facing the owner//Lift your butt slowly//The ties of the salaried workers who dream of having a job/are really heavy (Full text from “Geumran Market”)

For 17 years, the poet, who had been wandering around the city “addicted to verticality” (“Right Angle”) and settled down in the mudflats of Ganghwa Island to live in harmony with nature, does not hide his criticism of the “modern civilization that only has rigid erections” (“To the Civilization That Only Has Rigid Erections,” “Soft Power”).

The poet, who had been watching a flock of geese flying “soaked in radioactive rain” as if it were a “baptism of civilization,” eventually turns the “bright light of nuclear energy” that he had been cheering for into “darkness” (“Spring Rain, 2011, Korean Peninsula, Flew in from Fukushima”), and when “the fragments of the ozone layer shattered by the heat of industrialization/become lumps of lead/and become shotgun shells and bullets” that “are flying and getting lodged in our lungs,” he criticizes them by saying, “We must only be expelled voluntarily because they have turned life into a gun” (“Air Gun”).

The poet also laments the reality of developing “super corn/super soybeans/super cows” through genetic engineering, and says, “If that is the only way for people to survive,” then let’s “study how people can become small enough to fit into a “cockle bowl”” (from “At the Pesticide Store”), awakening a sense of nobility in nature and awe for life.

Water was the law/They say law is water//I learned about life by looking at water/But a speck of dust is trying to teach water//Borrowing the power of flowing water/And trapping water and putting it to practical use are quite different//If you don't know the use of uselessness/And you say you're making a monster of the rivers and mountains//How can you hear the sound of water/The blood of spring will be diluted (Full text from "The Grand Canal Delusion")

Ham Min-bok's poetry is an unadorned record of life.

The poet does not take lightly any moment of life, but rather embraces it with precious meaning, and approaches all beings in the world with a heartfelt affection.

His poetry is warm yet poor because it has the positive power to raise up poverty.

His poetry, which hopes to “shake so as not to be shaken/sway so as not to be shaken/stretch out branches and sprout leaves” (“Shaking”) and “can quench the thirst of those who have walked a long way” (“Used Tire 3”), will be a warm comfort to all those who dream of a better life and society, a world different from the present.

Like spring rain that moistens the dry land.

Hot and deep/resolutely/loving every moment/you have to live by putting into practice right away the very things you think are precious/but reality is different/the world turns smoothly with the power of different things/the stars and flowers seem beautiful/but it's always different/is death driving me from behind/is death pulling me from the front/and still/the world, the world/like an eyelid that cuts off tears/resolutely and deeply/hotly/gives birth to me every moment (Full text from "Like an Eyelid That Cuts Off Tears")

Poet Ham Min-bok, who has sung about the lives of the poor and marginalized in capitalist society with the power of 'innate longing' that springs from a good heart, has published a new poetry collection, 'Like an Eyelid That Cuts Tears.'

This is the fifth poetry collection, published eight years after the fourth poetry collection, “Soft Power” (Munhaksegyesa), published in 2005, ten years later.

Although it is a rather slow pace compared to the current poetry landscape, it contains 70 masterpieces that are worthy of the weight of time, enough to justify the comment that “Ham Min-bok’s imagination is social capital that we should be willing to share” (Lee Moon-jae, recommendation).

In this collection of poems, where the power of gentle lyricism stands out, the poet unfolds a philosophy of life imbued with the leisure to keep the spark of hope alive even in poverty, and a worldview of “existential thinking derived from experience” (Moon Hye-won, commentary) that dreams of a world where we live together with others.

The poems, written with the honest and plain 'voice of life' contained in refined language, without hasty rhetoric or exaggeration that plays at the fingertips, evoke warm empathy and leave a gentle resonance.

When I look at the full moon, my heart quickly becomes round/When I listen to the waning moon, my heart becomes hollow//The moon is/the whetstone of the heart//It brightly and sadly rules the sharp heart//The moon//The shadow I have encountered/is the mirror with the deepest lyricism (Full text from “Moon”)

The poet's thoughts on living an equal life with others are naturally revealed in life.

Interestingly, the poet focuses on objects that have lost their original function, such as a tape measure that is “wound up and measuring my body” (“Measurement Tape”), a broken clock that is heavier “than when it was alive” (“Dead Clock”), and a rusted, abandoned scale (“Crunchy Scale”), and obtains the basis for ontological thinking from them.

Here, the poet reads the shining objecthood of discarded objects with a fog-like vision that “erases the landscape/drawing the landscape” and “erases the building/drawing the time when there was no building,” and perceives the inherent nature of objects that have been “liberated from the world of appearance” (“Fog”).

I add to myself and subtract from myself/I read you//I lean towards you and then towards myself, waiting to be able to read myself through you//Focus on the other person, in the end, balance,/There is no actual burden thrown, but the burdens are lightened by each other (from the “scales”)

The reality of struggling to carry on with the arduous daily routine has long since become a sorrow felt by countless people living in this era, regardless of generation or class.

The poet also knows better than anyone the misery of such a life.

As he calmly unfolds the scenes of this shabby life, he subtly reveals the tenacious and determined side of all the directors.

The fish heads on the stalls/are all facing the owner//Lift your butt slowly//The ties of the salaried workers who dream of having a job/are really heavy (Full text from “Geumran Market”)

For 17 years, the poet, who had been wandering around the city “addicted to verticality” (“Right Angle”) and settled down in the mudflats of Ganghwa Island to live in harmony with nature, does not hide his criticism of the “modern civilization that only has rigid erections” (“To the Civilization That Only Has Rigid Erections,” “Soft Power”).

The poet, who had been watching a flock of geese flying “soaked in radioactive rain” as if it were a “baptism of civilization,” eventually turns the “bright light of nuclear energy” that he had been cheering for into “darkness” (“Spring Rain, 2011, Korean Peninsula, Flew in from Fukushima”), and when “the fragments of the ozone layer shattered by the heat of industrialization/become lumps of lead/and become shotgun shells and bullets” that “are flying and getting lodged in our lungs,” he criticizes them by saying, “We must only be expelled voluntarily because they have turned life into a gun” (“Air Gun”).

The poet also laments the reality of developing “super corn/super soybeans/super cows” through genetic engineering, and says, “If that is the only way for people to survive,” then let’s “study how people can become small enough to fit into a “cockle bowl”” (from “At the Pesticide Store”), awakening a sense of nobility in nature and awe for life.

Water was the law/They say law is water//I learned about life by looking at water/But a speck of dust is trying to teach water//Borrowing the power of flowing water/And trapping water and putting it to practical use are quite different//If you don't know the use of uselessness/And you say you're making a monster of the rivers and mountains//How can you hear the sound of water/The blood of spring will be diluted (Full text from "The Grand Canal Delusion")

Ham Min-bok's poetry is an unadorned record of life.

The poet does not take lightly any moment of life, but rather embraces it with precious meaning, and approaches all beings in the world with a heartfelt affection.

His poetry is warm yet poor because it has the positive power to raise up poverty.

His poetry, which hopes to “shake so as not to be shaken/sway so as not to be shaken/stretch out branches and sprout leaves” (“Shaking”) and “can quench the thirst of those who have walked a long way” (“Used Tire 3”), will be a warm comfort to all those who dream of a better life and society, a world different from the present.

Like spring rain that moistens the dry land.

Hot and deep/resolutely/loving every moment/you have to live by putting into practice right away the very things you think are precious/but reality is different/the world turns smoothly with the power of different things/the stars and flowers seem beautiful/but it's always different/is death driving me from behind/is death pulling me from the front/and still/the world, the world/like an eyelid that cuts off tears/resolutely and deeply/hotly/gives birth to me every moment (Full text from "Like an Eyelid That Cuts Off Tears")

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: February 20, 2013

- Page count, weight, size: 136 pages | 166g | 128*188*20mm

- ISBN13: 9788936423575

- ISBN10: 8936423576

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)