History of Disability (Recovery)

|

Description

Book Introduction

If Pain Becomes the Path, If Our Body Is the World Translation and commentary by Seoul National University Associate Professor Kim Seung-seop! The third journey, questioning a healthy society while thinking about the body. Definition of the body, definition of normalcy, and the chronicle of that struggle “Now our bodies will define us.” Sometimes I hear people say, “I met you in person and found you to be an inclusive and cheerful person (despite your disability).” Bae Bok-ju, former head of the Disabled Women's Solidarity (currently deputy leader of the Justice Party), says that while these words are complimentary, they are also words of prejudice. One perception is presupposed here. It means “despite having a disability.” Bae Bok-ju says that her disability is a point of tension that distinguishes and borders between normal and abnormal, and that the environment and perception of society serve as criteria for positioning disabilities. Kim E. Nielsen Nielsen) also states in his book, A Disability History of the US (2012), that the concept of 'disability' is not a fixed concept but a changing concept. Kim Nielsen, who studies disability studies, history, and women's studies at the University of Toledo, chronicles American history with disability at the center. It shows what disability is and how it has been defined in different societies. Because this process is also a history of changing standards for citizens and non-citizens, normal and abnormal, it also makes us look back on the common sense of our society today. Many people today view disability as a medical problem that needs to be treated. In this perspective, people with physical defects become 'disabled people', and people without such defects become 'non-disabled people'. Kim Nielsen argues that this view of disability as an ahistorical and unchangeable concept erases the diverse and rich lives of countless disabled people. "A History of Disability" revisits and rereads American history through the prism of disability, questioning the definition of the body and normalcy and presenting a new perspective. This book was translated by Associate Professor Seungseop Kim of Seoul National University Graduate School of Public Health, who has been thinking about a healthy society through the body in books such as “If Pain Is to Become a Path” and “If Our Body Is the World,” as part of his efforts. We took pains to clearly convey the book's problematic awareness and message, such as translating the expression "Able-Bodiedness," which is a concept contrasting with disability and is qualified as a full citizen, into "capable body." The translator's notes are evenly distributed to provide more reading material. Bae Bok-ju (Deputy Leader of the Justice Party, former Representative of the Disabled Women’s Solidarity) and Kim Won-young (author of ‘A Defense for the Disqualified’) wrote letters of recommendation. |

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Translator's Note

Entering

time

Chapter 1: The soul chooses the body in which it will reside.

: Native peoples of North America, before 1492

Chapter 2 The Poor, the Wicked, and the Sick

: Colonial communities, 1492–1700

Chapter 3: The Poor Thing Was Thrown into the Sea

: Late colonial period, 1700–1776

Chapter 4: The Abnormal and the Dependent

: The Birth of the Citizen, 1776–1865

Chapter 5 I have a disability, so I need to find a job that isn't hard labor.

: Institutionalization of Disability, 1865–1890

Chapter 6: Three generations of idiots are enough.

: The Century of Progress, 1890–1927

Chapter 7 We Don't Want a Tin Cup

: Laying the foundation and creating the stage, 1927-1968

Chapter 8 I think I'm an activist.

I think exercise is something that gives the mind a sense of purpose.

: Rights and Denied Rights, Since 1968

Epilogue

main

Search

Entering

time

Chapter 1: The soul chooses the body in which it will reside.

: Native peoples of North America, before 1492

Chapter 2 The Poor, the Wicked, and the Sick

: Colonial communities, 1492–1700

Chapter 3: The Poor Thing Was Thrown into the Sea

: Late colonial period, 1700–1776

Chapter 4: The Abnormal and the Dependent

: The Birth of the Citizen, 1776–1865

Chapter 5 I have a disability, so I need to find a job that isn't hard labor.

: Institutionalization of Disability, 1865–1890

Chapter 6: Three generations of idiots are enough.

: The Century of Progress, 1890–1927

Chapter 7 We Don't Want a Tin Cup

: Laying the foundation and creating the stage, 1927-1968

Chapter 8 I think I'm an activist.

I think exercise is something that gives the mind a sense of purpose.

: Rights and Denied Rights, Since 1968

Epilogue

main

Search

Detailed image

Into the book

As is the nature of democracy, we all live dependent on others.

We all care for others and are cared for by others.

(…) We are interdependent beings.

As historian Linda Kerber has pointed out in her analysis of the sexist elements of the American ideal of individualism, “The myth of the lone individual is a metaphor, a rhetorical device.

In real life, no one is self-made, and very few people are completely alone.” In reality, dependence is not a bad thing.

Dependence exists at the heart of every human life.

Dependence creates community and democracy.

--- p.19~20, from “Introduction”

Most indigenous communities did not have a word or concept equivalent to today's term 'disability'.

Indigenous researchers and activists Dorothy Lonewolf Miller (Blackfoot) and Jenny R.

Joe (Navajo) says some indigenous tribes define disability based on social relationships rather than physical conditions.

In indigenous cultures, disability was something that occurred when someone had no or weak connections to the community.

Even if an individual has a defect, a disability arises only when that person is unable to participate in the reciprocal activities of the community or is removed from those relationships.

For example, if a young man with a cognitive impairment has the ability to carry water, he may be a talented individual.

If so, that was the man's talent.

If you can fulfill your role well in a community that needs water, you can live as an important member of the community without stigma.

He participated in reciprocal activities and lived in balance.

--- p.41~42, from “Chapter 1”

Among European women in North America, Hutchinson and Dyer were threats to religious, political, and gender hierarchies.

According to John Winthrop, the monstrous sins they committed were literally manifested in the monstrous beings that developed in their wombs, and giving birth to these creatures proved that the women were sinners.

As Winthrop argued, the baby's deformed body symbolized the mother's sin.

It was believed that the more heinous the sin, the more monstrous the baby's body would be transformed.

As a result of women's challenge to both patriarchy and theological authority, not only Dyer and Hutchinson's bodies, but also the bodies of their stillborn children, were profoundly transformed and horrified.

For European colonial settlers, disability was a material reality, but it also functioned as a powerful metaphor and symbol.

--- p.82~83, from “Chapter 2”

The concept of disability has been used to justify legally established inequalities.

After the American Revolution, there was a proliferation of private and public institutions that defined and organized people with unfit bodies. (…) The process of creating institutions and increasing related regulations was accompanied by the definition of “normal” and “abnormal,” “ableness” and “disability.”

Citizens who were deemed mentally ill, incompetent, or physically incapable of supporting themselves financially were increasingly institutionalized.

There has also been a growing trend of restricting voting rights on the grounds of mental incapacity.

Federal and state governments have begun to tighten immigration laws that restrict the entry of people with disabilities.

When a person was considered unfit but was deemed to be salvageable or worthy of being saved, he or she was given the opportunity to be educated.

--- p.116~117, from Chapter 4

The history of disability in America, like American history as a whole, is a complex and contradictory story.

It is a story about plundered land and bodies.

It's a story about right and wrong, about devastation and destruction, about defeat and stubborn persistence, about beauty and elegance, about tragedy and sorrow, about transformative ideas, about the reinvention of the self.

In the words of white, disabled, queer writer and activist Ellie Clare, “It’s a brave and uproarious story about reclaiming our bodies and changing the world.”

We all care for others and are cared for by others.

(…) We are interdependent beings.

As historian Linda Kerber has pointed out in her analysis of the sexist elements of the American ideal of individualism, “The myth of the lone individual is a metaphor, a rhetorical device.

In real life, no one is self-made, and very few people are completely alone.” In reality, dependence is not a bad thing.

Dependence exists at the heart of every human life.

Dependence creates community and democracy.

--- p.19~20, from “Introduction”

Most indigenous communities did not have a word or concept equivalent to today's term 'disability'.

Indigenous researchers and activists Dorothy Lonewolf Miller (Blackfoot) and Jenny R.

Joe (Navajo) says some indigenous tribes define disability based on social relationships rather than physical conditions.

In indigenous cultures, disability was something that occurred when someone had no or weak connections to the community.

Even if an individual has a defect, a disability arises only when that person is unable to participate in the reciprocal activities of the community or is removed from those relationships.

For example, if a young man with a cognitive impairment has the ability to carry water, he may be a talented individual.

If so, that was the man's talent.

If you can fulfill your role well in a community that needs water, you can live as an important member of the community without stigma.

He participated in reciprocal activities and lived in balance.

--- p.41~42, from “Chapter 1”

Among European women in North America, Hutchinson and Dyer were threats to religious, political, and gender hierarchies.

According to John Winthrop, the monstrous sins they committed were literally manifested in the monstrous beings that developed in their wombs, and giving birth to these creatures proved that the women were sinners.

As Winthrop argued, the baby's deformed body symbolized the mother's sin.

It was believed that the more heinous the sin, the more monstrous the baby's body would be transformed.

As a result of women's challenge to both patriarchy and theological authority, not only Dyer and Hutchinson's bodies, but also the bodies of their stillborn children, were profoundly transformed and horrified.

For European colonial settlers, disability was a material reality, but it also functioned as a powerful metaphor and symbol.

--- p.82~83, from “Chapter 2”

The concept of disability has been used to justify legally established inequalities.

After the American Revolution, there was a proliferation of private and public institutions that defined and organized people with unfit bodies. (…) The process of creating institutions and increasing related regulations was accompanied by the definition of “normal” and “abnormal,” “ableness” and “disability.”

Citizens who were deemed mentally ill, incompetent, or physically incapable of supporting themselves financially were increasingly institutionalized.

There has also been a growing trend of restricting voting rights on the grounds of mental incapacity.

Federal and state governments have begun to tighten immigration laws that restrict the entry of people with disabilities.

When a person was considered unfit but was deemed to be salvageable or worthy of being saved, he or she was given the opportunity to be educated.

--- p.116~117, from Chapter 4

The history of disability in America, like American history as a whole, is a complex and contradictory story.

It is a story about plundered land and bodies.

It's a story about right and wrong, about devastation and destruction, about defeat and stubborn persistence, about beauty and elegance, about tragedy and sorrow, about transformative ideas, about the reinvention of the self.

In the words of white, disabled, queer writer and activist Ellie Clare, “It’s a brave and uproarious story about reclaiming our bodies and changing the world.”

--- p.316~317, from Chapter 8

Publisher's Review

If Pain Becomes the Path, If Our Body Is the World

Translated and commented by Professor Kim Seung-seop of Korea University!

The third journey, questioning a healthy society while thinking about the body.

Is independence good and dependence bad?

Are disabled people dependent and non-disabled people independent?

“Dependence exists at the heart of every human life.”

As competent citizens, we must be able to “stand on our own two feet” and “speak for ourselves.”

Kim Nielsen, the author of this book, notes that in these narratives, independence is good and dependence is bad.

Dependence simply means a weakness of relying on others, and it runs counter to the ideal American values of independence and autonomy.

Korean society is no different in giving independence a positive meaning and dependence a negative meaning.

And when disability is equated with dependence, disability becomes a stigma.

Disabled people are labeled as 'inferior citizens'.

So is dependence a bad thing? Are non-disabled people independent?

Kim Nielsen says:

As is the nature of democracy, we all depend on others to survive, and dependence is not limited to people with disabilities; we are all interdependent beings.

He quotes historian Linda Kerber, who points out the American ideal of individualism.

“No one in real life is self-made, and very few people are completely alone.”

Kim Nielsen subverts meaning and expands value, saying, “Dependence exists at the heart of all human life,” and “Dependence creates community and democracy.”

In this way, 『History of Disability』 presents historical examples and asks questions, and questions the common notions we have taken for granted.

It leads to and proposes subversive imagination.

What a non-disabled society forces

Against shame, silence and isolation

“A brave and vibrant story about reclaiming our bodies and changing the world.”

Ableist attitudes can be overt, such as discrimination against people with disabilities in employment, but they can also operate in more subtle ways, such as at a standing concert where everyone is expected to stand for two hours.

Kim Nielsen argues that ableism, like racism, sexism, and homophobia, impacts individual lives and builds up within social structures.

This book also tells the story of the struggle against the silence, shame, and isolation imposed by ableism.

Kim Won-young (actor, lawyer, author of ‘A Defense for the Disqualified’), who wrote the letter of recommendation, says this:

“The day I realized that my body, which had suffered from an illness or an accident, was classified as ‘disabled,’ I felt like I had lost my memory and was banished to a strange land.

This book, focusing on North America, says the truth of history is the opposite.

This is because it shows that disability was constructed and arbitrarily mobilized within the logic of oppression and violence of colonialism, racism, gender discrimination, and ableism, amidst the domination and resistance of 'independent and capable' bodies that crossed from Europe to North America.

So to speak, becoming disabled does not mean that you are alone in a new world, but that a new history of oppression and discrimination has arrived in the world in which you (we) live.

Therefore, when this book reaches its final chapter and tells the stories of people who consider disability a source of pride, it is not difficult to understand that this pride is not simply a mental victory, but a solid heart connected to the long lineage of the world we live in.”

This book shows how structures define and oppress individuals, ultimately leading to the struggles and achievements of those who fought against that oppression.

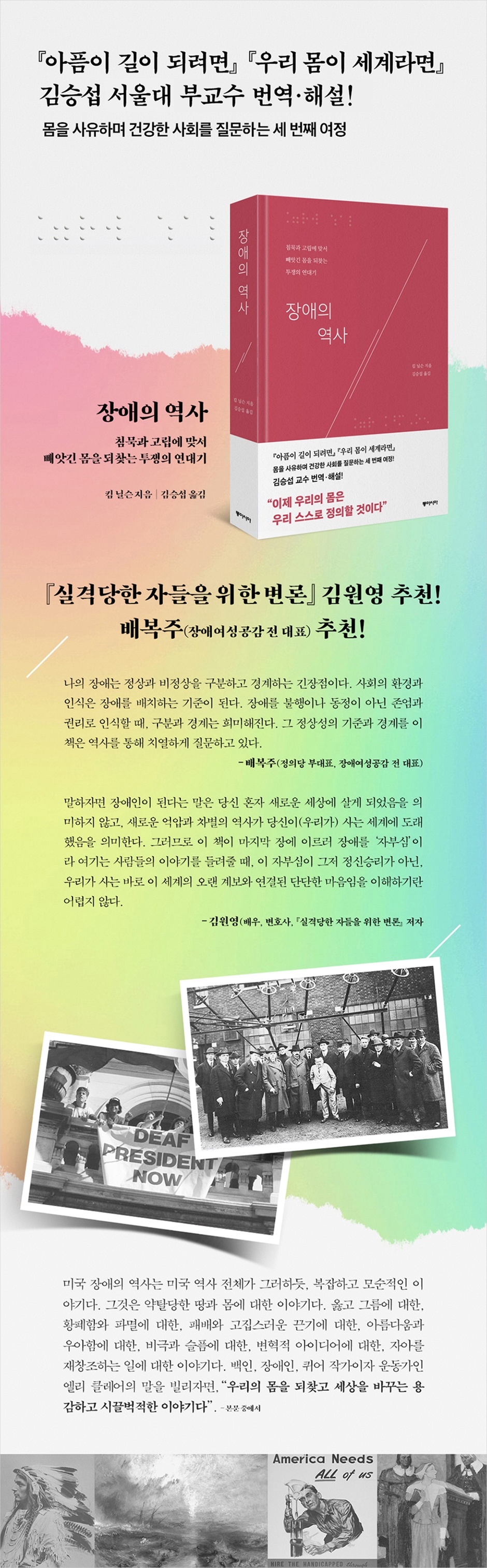

For example, in 1988, deaf students at Gallaudet University, a school for the deaf in the United States, staged a civil disobedience movement, chanting, "Deaf President Now."

The struggle resulted in the victory of appointing the first non-Chinese president.

These historical scenes can also be seen through the photographic materials added to the Korean edition, adding to the fun of reading and viewing.

Translated and commented by Professor Kim Seung-seop of Korea University!

The third journey, questioning a healthy society while thinking about the body.

Is independence good and dependence bad?

Are disabled people dependent and non-disabled people independent?

“Dependence exists at the heart of every human life.”

As competent citizens, we must be able to “stand on our own two feet” and “speak for ourselves.”

Kim Nielsen, the author of this book, notes that in these narratives, independence is good and dependence is bad.

Dependence simply means a weakness of relying on others, and it runs counter to the ideal American values of independence and autonomy.

Korean society is no different in giving independence a positive meaning and dependence a negative meaning.

And when disability is equated with dependence, disability becomes a stigma.

Disabled people are labeled as 'inferior citizens'.

So is dependence a bad thing? Are non-disabled people independent?

Kim Nielsen says:

As is the nature of democracy, we all depend on others to survive, and dependence is not limited to people with disabilities; we are all interdependent beings.

He quotes historian Linda Kerber, who points out the American ideal of individualism.

“No one in real life is self-made, and very few people are completely alone.”

Kim Nielsen subverts meaning and expands value, saying, “Dependence exists at the heart of all human life,” and “Dependence creates community and democracy.”

In this way, 『History of Disability』 presents historical examples and asks questions, and questions the common notions we have taken for granted.

It leads to and proposes subversive imagination.

What a non-disabled society forces

Against shame, silence and isolation

“A brave and vibrant story about reclaiming our bodies and changing the world.”

Ableist attitudes can be overt, such as discrimination against people with disabilities in employment, but they can also operate in more subtle ways, such as at a standing concert where everyone is expected to stand for two hours.

Kim Nielsen argues that ableism, like racism, sexism, and homophobia, impacts individual lives and builds up within social structures.

This book also tells the story of the struggle against the silence, shame, and isolation imposed by ableism.

Kim Won-young (actor, lawyer, author of ‘A Defense for the Disqualified’), who wrote the letter of recommendation, says this:

“The day I realized that my body, which had suffered from an illness or an accident, was classified as ‘disabled,’ I felt like I had lost my memory and was banished to a strange land.

This book, focusing on North America, says the truth of history is the opposite.

This is because it shows that disability was constructed and arbitrarily mobilized within the logic of oppression and violence of colonialism, racism, gender discrimination, and ableism, amidst the domination and resistance of 'independent and capable' bodies that crossed from Europe to North America.

So to speak, becoming disabled does not mean that you are alone in a new world, but that a new history of oppression and discrimination has arrived in the world in which you (we) live.

Therefore, when this book reaches its final chapter and tells the stories of people who consider disability a source of pride, it is not difficult to understand that this pride is not simply a mental victory, but a solid heart connected to the long lineage of the world we live in.”

This book shows how structures define and oppress individuals, ultimately leading to the struggles and achievements of those who fought against that oppression.

For example, in 1988, deaf students at Gallaudet University, a school for the deaf in the United States, staged a civil disobedience movement, chanting, "Deaf President Now."

The struggle resulted in the victory of appointing the first non-Chinese president.

These historical scenes can also be seen through the photographic materials added to the Korean edition, adding to the fun of reading and viewing.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Publication date: November 5, 2020

- Page count, weight, size: 360 pages | 550g | 140*215*25mm

- ISBN13: 9788962623512

- ISBN10: 896262351X

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)