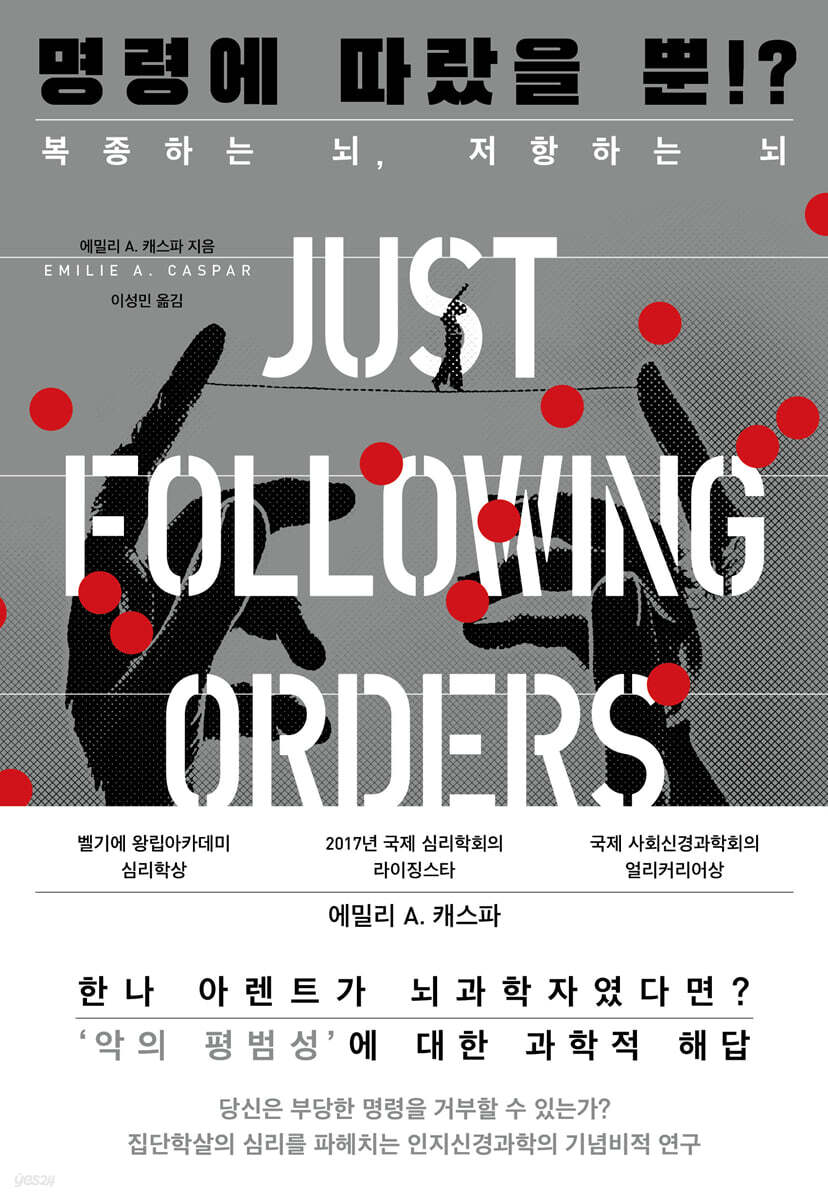

Just following orders!?

|

Description

Book Introduction

- A word from MD

-

The problem is the submissive brainThe reason we were unable to prevent violence and disasters like Auschwitz and the Rwandan civil war was because of people who obeyed unjust orders.

Of course, there were people who resisted.

Where does this difference come from? Neuroscientist Emily A.

Caspar confronts the issues of authority and obedience with a neuroscientific approach, along with the testimony of the perpetrators of the massacre.

January 31, 2025. Natural Science PD Son Min-gyu

What happens in a submissive brain?

Cognitive neuroscience research on human command follower behavior

A Scientific Answer to the 'Banity of Evil'

Those who participated in genocide or state violence all say during their trials that they were “just following orders.”

Were they truly just following orders? And can simply following orders actually lead humans to commit unjust and cruel acts? "Just Following Orders!?: The Obeying Brain, the Resisting Brain" by cognitive neuroscientist Emily A.

This book reveals the cognitive neurological processes that occur in the brains of those who follow orders, in order to understand the root of human behavior that obeys authority.

The author analyzes extensive social, psychological, and cognitive neuroscience data, along with his own research exploring the mechanisms of obedience, to provide a comprehensive understanding of genocide and collective violence.

It is particularly impressive that he visited Rwanda and Cambodia, where genocides occurred, interviewed the actual perpetrators of the massacres, and synthesized the results with his experiments.

Moreover, the book uses this information to explore ways to prevent our society from becoming tainted by collective violence.

Cognitive neuroscience research on human command follower behavior

A Scientific Answer to the 'Banity of Evil'

Those who participated in genocide or state violence all say during their trials that they were “just following orders.”

Were they truly just following orders? And can simply following orders actually lead humans to commit unjust and cruel acts? "Just Following Orders!?: The Obeying Brain, the Resisting Brain" by cognitive neuroscientist Emily A.

This book reveals the cognitive neurological processes that occur in the brains of those who follow orders, in order to understand the root of human behavior that obeys authority.

The author analyzes extensive social, psychological, and cognitive neuroscience data, along with his own research exploring the mechanisms of obedience, to provide a comprehensive understanding of genocide and collective violence.

It is particularly impressive that he visited Rwanda and Cambodia, where genocides occurred, interviewed the actual perpetrators of the massacres, and synthesized the results with his experiments.

Moreover, the book uses this information to explore ways to prevent our society from becoming tainted by collective violence.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Translator's Note 005

Prologue: To the Reader 010

Introduction: Understanding is essential to preventing genocide. 022

The Role of Neuroscience 030

Neuroscientists rarely encounter non-WEIRD populations 034

Conducting Interviews as a Research Methodology 039

Interview Progress 045

About this book 051

Every Life Matters 059

Chapter 1: Listening to the Perpetrators of Genocide 062

The Challenges of Conducting Interviews in Rwanda and Cambodia 068

Interview Interpretation 080

Group Attack 082

Obedience to (bad) authority 084

Compulsory Participation 090

Conclusion 106

Chapter 2 A Brief History of Experimental Research on Obedience 108

The Birth of Obedience Research: Insights from Early Experimental Research 112

Milgram's Obedience Experiment 116

Other studies using a similar approach to Milgram's 121

Flaws in Milgram-Like Studies 126

Obedience Studies After Milgram's Study 130

A New Experimental Approach to Studying Obedience 133

Can Laboratory Experiments Reflect Real-Life Atrocities? 147

Conclusion 148

Chapter 3: How Do We Take Ownership and Responsibility for Our Actions? 150

Subjective Consciousness and the Human Brain 157

Taking Responsibility for Your Actions 162

Diffusion of Responsibility Among Individuals 167

The neural origins of reduced agency and responsibility in submissive situations 173

The Impact of a Highly Hierarchical Social Structure 181

Conclusion 186

Chapter 4: Moral Emotions in Obedience 188

The brain is wired to feel empathy 191

Increased aggression, decreased empathy, and empathy modulation 203

'Us' vs. 'Them' - The Road to Dehumanization and Mass Atrocities 214

The Impact of Dehumanization on Human Behavior 223

Obeying orders affects the neural basis of guilt 229

Conclusion 234

Chapter 5 When giving an order, 236 occur in the commander's brain.

On the Complexity of Hierarchical Chains 243

How often are leaders held accountable for the atrocities committed under their command? 245

Moral Decision-Making by Leaders 251

Commander and Intermediary Brain 256

Commanding Machines: A New Challenge for Hierarchical Chains? 262

Chapter 6: Desolation is Everywhere 266

Understanding Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder 271

Stressful Events Change the Brain 275

The Unspoken Suffering of the Fighters 280

The Moral Consequences of War 283

PTSD in war trauma victims 288

The Concept of Resilience 294

Can the aftereffects of trauma be passed down through generations? 298

War, Trauma, Conflict, War, Trauma, Conflict: The Endless Cycle 303

Chapter 7 Conclusion: How Do Ordinary People Fight Immorality? 306

Discovering the Saviors in History 313

Who risks everything to help others? 319

The Neuroscience of Costly Helping Behaviors 325

How to Make People Disobedient in a Laboratory Environment 329

The Neuroscience of Resistance to Immoral Commands 334

Conclusion 340

Epilogue: Horizon of Hope 342

Acknowledgements 346

References 350

Search 376

Prologue: To the Reader 010

Introduction: Understanding is essential to preventing genocide. 022

The Role of Neuroscience 030

Neuroscientists rarely encounter non-WEIRD populations 034

Conducting Interviews as a Research Methodology 039

Interview Progress 045

About this book 051

Every Life Matters 059

Chapter 1: Listening to the Perpetrators of Genocide 062

The Challenges of Conducting Interviews in Rwanda and Cambodia 068

Interview Interpretation 080

Group Attack 082

Obedience to (bad) authority 084

Compulsory Participation 090

Conclusion 106

Chapter 2 A Brief History of Experimental Research on Obedience 108

The Birth of Obedience Research: Insights from Early Experimental Research 112

Milgram's Obedience Experiment 116

Other studies using a similar approach to Milgram's 121

Flaws in Milgram-Like Studies 126

Obedience Studies After Milgram's Study 130

A New Experimental Approach to Studying Obedience 133

Can Laboratory Experiments Reflect Real-Life Atrocities? 147

Conclusion 148

Chapter 3: How Do We Take Ownership and Responsibility for Our Actions? 150

Subjective Consciousness and the Human Brain 157

Taking Responsibility for Your Actions 162

Diffusion of Responsibility Among Individuals 167

The neural origins of reduced agency and responsibility in submissive situations 173

The Impact of a Highly Hierarchical Social Structure 181

Conclusion 186

Chapter 4: Moral Emotions in Obedience 188

The brain is wired to feel empathy 191

Increased aggression, decreased empathy, and empathy modulation 203

'Us' vs. 'Them' - The Road to Dehumanization and Mass Atrocities 214

The Impact of Dehumanization on Human Behavior 223

Obeying orders affects the neural basis of guilt 229

Conclusion 234

Chapter 5 When giving an order, 236 occur in the commander's brain.

On the Complexity of Hierarchical Chains 243

How often are leaders held accountable for the atrocities committed under their command? 245

Moral Decision-Making by Leaders 251

Commander and Intermediary Brain 256

Commanding Machines: A New Challenge for Hierarchical Chains? 262

Chapter 6: Desolation is Everywhere 266

Understanding Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder 271

Stressful Events Change the Brain 275

The Unspoken Suffering of the Fighters 280

The Moral Consequences of War 283

PTSD in war trauma victims 288

The Concept of Resilience 294

Can the aftereffects of trauma be passed down through generations? 298

War, Trauma, Conflict, War, Trauma, Conflict: The Endless Cycle 303

Chapter 7 Conclusion: How Do Ordinary People Fight Immorality? 306

Discovering the Saviors in History 313

Who risks everything to help others? 319

The Neuroscience of Costly Helping Behaviors 325

How to Make People Disobedient in a Laboratory Environment 329

The Neuroscience of Resistance to Immoral Commands 334

Conclusion 340

Epilogue: Horizon of Hope 342

Acknowledgements 346

References 350

Search 376

Detailed image

.jpg)

Into the book

The shocking truth is that the perpetrators are not so different from us.

For example, past studies have not found that jihadists who plan terrorist attacks have mental health problems.11 In fact, most of them are educated, married, and have children.

Although they felt lonely and isolated and were willing to participate in the movements of groups that shared values strongly connected to them, they did not suffer from mental illness.

Hannah Arendt, the renowned political philosopher and survivor of the Nazi genocide, had already concluded that Adolf Eichmann, one of the Nazis' chief planners, was not a monster.

Rather, he was seen as a bureaucratic clown who served the Führer and shared his ideology.

Jewish survivor Elie Wiesel said:

“The devil is that they were not devils.”

---p.39 From “Introduction, Conducting Interviews as a Research Methodology”

In fact, Milgram's study results were somewhat different from these kinds of self-predicted results.

There were 40 people who participated in Milgram's groundbreaking experiment.

Sixty-five percent of them applied the maximum voltage despite the learners screaming and pleading to stop the experiment.

What's important is that none of the participants asked to stop before the 300-volt shock intensity.

These results raise important questions.

Why did the participants obey? Why would a normal person inflict painful and even fatal electric shocks on another participant?

Milgram tried to explain the level of obedience he achieved through his research.

He explained that when people follow the experimenter's orders, they transfer their agency and responsibility to the experimenter.

They become 'thoughtless agents of action' and enter an 'agentic state'.

---p.119 From “Chapter 2 A Brief History of Experimental Research on Obedience, Milgram’s Obedience Experiment”

We observed that when following a command, subjects perceived the interval between the action and the tone to be longer than when they freely chose the action.

Participants actually reported that the interval between their action and the subsequent beep in the coercive condition was longer than the interval in the free-choice condition.

These results suggest that participants felt less agency over the outcomes of their actions when they were told what to do than when they made their own decisions.

Furthermore, this approach reduced the possibility that these results were influenced by social desirability, as participants were unable to link the time interval estimation task with their assessments of their own agency.

At first, this result really surprised us, because in both cases, whether people decided freely or were directed, they were the agents of their own actions.

There was no doubt who pressed the button, and the experiment did not use any brain stimulation technology to make them press the key.

Participants were simply told whether to shock the 'victim' or not.

In other words, all you had to do was execute the actions associated with the command.

---p.178-179 From “Chapter 3: How do we take ownership and responsibility for our actions? Neural sources of reduced subjectivity and responsibility in obedience situations”

The limbic system, commonly called the emotional brain, is a subcortical structure deep within the brain.

It is mainly related to emotions, emotional states, and behavioral patterns.

Research shows that witnessing another person's pain does not activate the entire pain processing system, but rather only a part of it, the limbic system, which plays a particularly important role.

This means that witnessing another person in pain does not actually cause a feeling of sensory pain, but rather an emotional and affective feeling of that pain.

In other words, you don't physically feel another person's pain, but you emotionally process and understand it.

---p.194-195 From “Chapter 4 Moral Emotions When Obeying, The Brain Is Set Up to Feel Empathy”

What's interesting is that everyone can modulate their empathy for the suffering of others.

In 2022, we conducted two studies in which participants were asked to simply watch pictures of painful or non-painful stimuli on a screen.

We recorded their brain activity with electroencephalography (EEG) and, as expected, observed that the brain processed painful and non-painful stimuli differently.

We also asked our participants to make two additional efforts.

First, in one condition, they were asked to develop empathy and feel more of the suffering of the person in the picture.

In another condition, participants were asked to lower their empathy and perceive the same painful stimulus as less painful.

The results were truly intriguing, as people were able to successfully modulate their neural responses to the suffering of the person in the picture.

---p.209-210 From “Chapter 4 Moral Emotions, Increased Aggression, Decreased Empathy, and Empathy Regulation When Obeying”

For example, some leaders prioritize their own interests over the interests of the society they lead, and thus make decisions that benefit themselves.

Some leaders feel pressured by powerful interest groups and lobbyists to influence decisions in their own interests.

Additionally, some leaders may lack a thorough understanding of the issues they are addressing and may make decisions without adequately considering the long-term impact on their citizens.

In such cases, leaders can use a self-regulating mechanism called moral disengagement to commit illegal acts without a guilty conscience.

Moral disengagement involves reframing one's actions to make them seem less harmful, to reduce awareness of the harm they cause others, or to minimize one's own responsibility.

---p.241-242 “Chapter 5 When giving an order, what happens in the commander’s brain?

It is noteworthy that the commanders with the lowest sense of agency when giving orders scored highest on the scale measuring psychopathic traits.

That is, psychopathic traits appear to increase the risk that people will not feel a sense of agency (and therefore responsibility) when giving orders.

This is particularly concerning given that past research has shown that psychopathic traits are very common among leaders in business and other fields.

(…) Taken together, these results suggest that when someone lacks agency or responsibility for their own actions, they may act more harmfully toward others.

---p.259-260 From “Chapter 5: When giving orders, the brain of the commander and the intermediary”

Therefore, soldiers must refuse unlawful orders, but must obey immoral orders to avoid being court-martialed.

Soldiers are often faced with very difficult tasks that require them to act against their own moral values because their job means following given orders.

The concept of 'moral injury' occurs in military veterans or those still serving in the military who witness or commit acts that violate moral values.

---p.283-284 From “Chapter 6: Desolation is Everywhere: The Moral Consequences of War”

Conflict is contagious.

It is deeply rooted in human nature to retaliate when someone hurts us.

However, revenge can also increase the risk of developing PTSD symptoms in the long term.

This desire for revenge can become even more intense when justice is not served.

For example, after the fall of the Khmer Rouge regime in Cambodia, citizens learned that past perpetrators had not been brought to justice and, in many cases, still held high government positions.

As everything around me became devastated, feelings of revenge often arose.

The presence of revenge creates the possibility that conflicts will continue across generations.

This increases the likelihood of new conflicts with similarly serious consequences.

It seems like an endless vicious cycle.

---p.303-304 From “Chapter 6: Desolation is Everywhere, War, Trauma, Conflict, War, Trauma, Conflict: An Endless Cycle”

Since the Orliners' landmark study, many researchers have sought to identify specific traits associated with rescue operations during war and genocide.

In a 2007 study, researchers observed that rescuers felt a greater sense of social responsibility and had a more altruistic moral outlook than bystanders.

They had higher empathic concern for others and were more willing to take risks.

These results were independent of demographic factors or situational differences.

Even though feeling compassion and empathy for Jews could lead to death, the rescue group showed a high level of compassion and empathy for those in need.

---p.320 From “Conclusion: How do ordinary people fight against immorality? Who risks everything to help others?”

In the painful electric shock studies I developed, the disobedience rate was very (very) low.

It was so low that no matter how many times it was run, it was difficult to do a reliable statistical analysis of disobedience.

So I had to find a different approach to ensure that at least some people would resist the order to harm others.

It took five years to systematically analyze the participants' post-test reports about why they followed my commands and to conduct six more experimental studies.

---p.329-330 From "Conclusion: How Ordinary People Fight Immoralities? How to Make People Disobedient in a Laboratory Environment"

Throughout the book, we have explored from a neuroscientific perspective the various neurocognitive mechanisms involved in prosocial behaviors, such as empathy, guilt, and agency.

We also observed that many processes occurring before and during genocide easily obscure its mechanisms.

For example, genocide often involves hate propaganda, dehumanization, and other forms of psychological manipulation that can influence individuals to engage in violence.

Genocides also often arise from long-standing conflicts, from the growing categorization of "us" versus "them."

Such tensions can fuel hatred and violence.

Furthermore, we observed that when people decided to follow the orders of an authority figure, their prosocial mechanisms also changed.

People experience a decrease in empathy for the victim's suffering and a weakening of guilt, responsibility, and agency.

These influences affect our ability to fully accept the consequences of our actions.

While it is important to hold perpetrators of genocide accountable, it is also crucial to take a nuanced, interdisciplinary approach to understanding the complex dynamics, such as the unconscious neural activity that contributes to perpetrating genocide.

This knowledge can then be used to develop interventions that promote empathy, moral courage, and independent thinking.

The key to prevention is understanding.

For example, past studies have not found that jihadists who plan terrorist attacks have mental health problems.11 In fact, most of them are educated, married, and have children.

Although they felt lonely and isolated and were willing to participate in the movements of groups that shared values strongly connected to them, they did not suffer from mental illness.

Hannah Arendt, the renowned political philosopher and survivor of the Nazi genocide, had already concluded that Adolf Eichmann, one of the Nazis' chief planners, was not a monster.

Rather, he was seen as a bureaucratic clown who served the Führer and shared his ideology.

Jewish survivor Elie Wiesel said:

“The devil is that they were not devils.”

---p.39 From “Introduction, Conducting Interviews as a Research Methodology”

In fact, Milgram's study results were somewhat different from these kinds of self-predicted results.

There were 40 people who participated in Milgram's groundbreaking experiment.

Sixty-five percent of them applied the maximum voltage despite the learners screaming and pleading to stop the experiment.

What's important is that none of the participants asked to stop before the 300-volt shock intensity.

These results raise important questions.

Why did the participants obey? Why would a normal person inflict painful and even fatal electric shocks on another participant?

Milgram tried to explain the level of obedience he achieved through his research.

He explained that when people follow the experimenter's orders, they transfer their agency and responsibility to the experimenter.

They become 'thoughtless agents of action' and enter an 'agentic state'.

---p.119 From “Chapter 2 A Brief History of Experimental Research on Obedience, Milgram’s Obedience Experiment”

We observed that when following a command, subjects perceived the interval between the action and the tone to be longer than when they freely chose the action.

Participants actually reported that the interval between their action and the subsequent beep in the coercive condition was longer than the interval in the free-choice condition.

These results suggest that participants felt less agency over the outcomes of their actions when they were told what to do than when they made their own decisions.

Furthermore, this approach reduced the possibility that these results were influenced by social desirability, as participants were unable to link the time interval estimation task with their assessments of their own agency.

At first, this result really surprised us, because in both cases, whether people decided freely or were directed, they were the agents of their own actions.

There was no doubt who pressed the button, and the experiment did not use any brain stimulation technology to make them press the key.

Participants were simply told whether to shock the 'victim' or not.

In other words, all you had to do was execute the actions associated with the command.

---p.178-179 From “Chapter 3: How do we take ownership and responsibility for our actions? Neural sources of reduced subjectivity and responsibility in obedience situations”

The limbic system, commonly called the emotional brain, is a subcortical structure deep within the brain.

It is mainly related to emotions, emotional states, and behavioral patterns.

Research shows that witnessing another person's pain does not activate the entire pain processing system, but rather only a part of it, the limbic system, which plays a particularly important role.

This means that witnessing another person in pain does not actually cause a feeling of sensory pain, but rather an emotional and affective feeling of that pain.

In other words, you don't physically feel another person's pain, but you emotionally process and understand it.

---p.194-195 From “Chapter 4 Moral Emotions When Obeying, The Brain Is Set Up to Feel Empathy”

What's interesting is that everyone can modulate their empathy for the suffering of others.

In 2022, we conducted two studies in which participants were asked to simply watch pictures of painful or non-painful stimuli on a screen.

We recorded their brain activity with electroencephalography (EEG) and, as expected, observed that the brain processed painful and non-painful stimuli differently.

We also asked our participants to make two additional efforts.

First, in one condition, they were asked to develop empathy and feel more of the suffering of the person in the picture.

In another condition, participants were asked to lower their empathy and perceive the same painful stimulus as less painful.

The results were truly intriguing, as people were able to successfully modulate their neural responses to the suffering of the person in the picture.

---p.209-210 From “Chapter 4 Moral Emotions, Increased Aggression, Decreased Empathy, and Empathy Regulation When Obeying”

For example, some leaders prioritize their own interests over the interests of the society they lead, and thus make decisions that benefit themselves.

Some leaders feel pressured by powerful interest groups and lobbyists to influence decisions in their own interests.

Additionally, some leaders may lack a thorough understanding of the issues they are addressing and may make decisions without adequately considering the long-term impact on their citizens.

In such cases, leaders can use a self-regulating mechanism called moral disengagement to commit illegal acts without a guilty conscience.

Moral disengagement involves reframing one's actions to make them seem less harmful, to reduce awareness of the harm they cause others, or to minimize one's own responsibility.

---p.241-242 “Chapter 5 When giving an order, what happens in the commander’s brain?

It is noteworthy that the commanders with the lowest sense of agency when giving orders scored highest on the scale measuring psychopathic traits.

That is, psychopathic traits appear to increase the risk that people will not feel a sense of agency (and therefore responsibility) when giving orders.

This is particularly concerning given that past research has shown that psychopathic traits are very common among leaders in business and other fields.

(…) Taken together, these results suggest that when someone lacks agency or responsibility for their own actions, they may act more harmfully toward others.

---p.259-260 From “Chapter 5: When giving orders, the brain of the commander and the intermediary”

Therefore, soldiers must refuse unlawful orders, but must obey immoral orders to avoid being court-martialed.

Soldiers are often faced with very difficult tasks that require them to act against their own moral values because their job means following given orders.

The concept of 'moral injury' occurs in military veterans or those still serving in the military who witness or commit acts that violate moral values.

---p.283-284 From “Chapter 6: Desolation is Everywhere: The Moral Consequences of War”

Conflict is contagious.

It is deeply rooted in human nature to retaliate when someone hurts us.

However, revenge can also increase the risk of developing PTSD symptoms in the long term.

This desire for revenge can become even more intense when justice is not served.

For example, after the fall of the Khmer Rouge regime in Cambodia, citizens learned that past perpetrators had not been brought to justice and, in many cases, still held high government positions.

As everything around me became devastated, feelings of revenge often arose.

The presence of revenge creates the possibility that conflicts will continue across generations.

This increases the likelihood of new conflicts with similarly serious consequences.

It seems like an endless vicious cycle.

---p.303-304 From “Chapter 6: Desolation is Everywhere, War, Trauma, Conflict, War, Trauma, Conflict: An Endless Cycle”

Since the Orliners' landmark study, many researchers have sought to identify specific traits associated with rescue operations during war and genocide.

In a 2007 study, researchers observed that rescuers felt a greater sense of social responsibility and had a more altruistic moral outlook than bystanders.

They had higher empathic concern for others and were more willing to take risks.

These results were independent of demographic factors or situational differences.

Even though feeling compassion and empathy for Jews could lead to death, the rescue group showed a high level of compassion and empathy for those in need.

---p.320 From “Conclusion: How do ordinary people fight against immorality? Who risks everything to help others?”

In the painful electric shock studies I developed, the disobedience rate was very (very) low.

It was so low that no matter how many times it was run, it was difficult to do a reliable statistical analysis of disobedience.

So I had to find a different approach to ensure that at least some people would resist the order to harm others.

It took five years to systematically analyze the participants' post-test reports about why they followed my commands and to conduct six more experimental studies.

---p.329-330 From "Conclusion: How Ordinary People Fight Immoralities? How to Make People Disobedient in a Laboratory Environment"

Throughout the book, we have explored from a neuroscientific perspective the various neurocognitive mechanisms involved in prosocial behaviors, such as empathy, guilt, and agency.

We also observed that many processes occurring before and during genocide easily obscure its mechanisms.

For example, genocide often involves hate propaganda, dehumanization, and other forms of psychological manipulation that can influence individuals to engage in violence.

Genocides also often arise from long-standing conflicts, from the growing categorization of "us" versus "them."

Such tensions can fuel hatred and violence.

Furthermore, we observed that when people decided to follow the orders of an authority figure, their prosocial mechanisms also changed.

People experience a decrease in empathy for the victim's suffering and a weakening of guilt, responsibility, and agency.

These influences affect our ability to fully accept the consequences of our actions.

While it is important to hold perpetrators of genocide accountable, it is also crucial to take a nuanced, interdisciplinary approach to understanding the complex dynamics, such as the unconscious neural activity that contributes to perpetrating genocide.

This knowledge can then be used to develop interventions that promote empathy, moral courage, and independent thinking.

The key to prevention is understanding.

---p.344 From "Epilogue: Horizon of Hope"

Publisher's Review

“If Hannah Arendt were a neuroscientist, she would have written a book like this.”

Why did they obey orders?

Cognitive neuroscience research on humans engaging in collective violence

“Historically, the most terrible things—wars, genocide, slavery—have not happened because of disobedience, but because of obedience.”

“I was just following orders.” This is a statement of evasion of responsibility that can be heard from all participants, including those responsible, when a state-sponsored violence or massacre occurs.

This is also the defense presented by the majority of the 24 leaders indicted at the First International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg, which held them accountable for war crimes during World War II.

Of course, their excuses were not taken into account, and all but three were found guilty, with twelve of the defendants sentenced to death.

Nevertheless, how to punish the enlisted men and non-commissioned officers who carried out brutal acts under orders at the lowest level of the command chain became a subject of debate.

Do those who follow orders under duress temporarily lose their free will? Even so, are such brutal acts perpetrated simply because they're ordered to do so?

"Just Following Orders!?: The Obedient Brain, the Resisting Brain" is written by Emily A., Associate Professor of Experimental Psychology at Ghent University in Belgium.

This book is a compilation of Caspar's research, which he has been conducting since 2016, and reveals the cognitive neuroscientific processes that occur in the human brain when obeying commands.

The book also analyzes extensive social, psychological, and cognitive neuroscience data to provide comprehensive knowledge on the causes of genocide and mass violence.

What is special is that it does not remain within a limited research framework.

The author acknowledges the limitations of laboratory research, which is limited to controlled environments and small populations, and synthesizes the experimental results after visiting Rwanda and Cambodia, where genocides occurred, and interviewing actual perpetrators of the massacres.

Moreover, based on this information, we are exploring ways to prevent our society from becoming tainted by collective violence.

Emily Caspar, a neuropsychologist and cognitive neuroscience major, has studied how obedience to authority and commands affects individual behavior.

The uniqueness of the Caspar study lies in the objective observation of changes in the subject that occur during the command and execution process at the level of cognitive neuroscience.

While previous psychological research has focused on demonstrating the brutality with which humans can obey orders, his research illuminates the changes in the brains of those who follow orders and their implications.

His doctoral thesis, "Coercion Changes the Human Brain's Subjective Consciousness," caused a sensation with its neuroscientific approach and immediately captured the attention of the psychology and scientific communities.

For this paper, Caspar won the 2016 Royal Belgian Academy Prize in Psychology, which is awarded every three years for the best psychology doctoral dissertation, and in the same year, he won both the William James Prize and the Evens Prize in Science from the Society for the Scientific Study of Consciousness, which are awarded for related research.

A series of studies on the same topic followed, leading to his being nominated for the Rising Star Award of the International Psychological Association in 2017 and winning the Early Career Award of the International Society of Social Neuroscience in 2023.

Both of these awards are for early-career researchers with little research experience, and they are a testament to the significant attention Caspar is receiving.

What happens in a submissive brain?

Finding the Neural Roots of Command-Following Behavior

“More than that, I wanted to understand what happens in people’s brains when they agree to obey orders that cause pain to others.”

Emily Caspar explains that her research was designed under the influence of the Milgram experiment.

The 'Obedience to Authority' study conducted by psychologist Stanley Milgram in 1961 was an experiment to see how much pain participants could inflict on others when given orders by the experimenter.

The experiment was shocking, with 65 percent of participants applying the maximum voltage of 450 volts on command, "despite the screams and pleas" of the other person.

This experiment became the most important reference in obedience research, and subsequent similar experiments by other researchers confirmed that the results of the Milgram experiment were repeated.

The Milgram experiment and other similar experiments have all shown that humans can inflict significant harm on other humans simply by following orders, without any specific motivation.

However, Emily Caspar points out that the Milgram experiment and similar experiments “only tell us whether or not individuals will obey orders from authority figures in a given situation.”

Previous research has shown that “we cannot understand how people can commit atrocities when they are following orders.”

Starting with 'how', the author devises an experiment that combines cognitive neuroscience with the Milgram study.

That is, “what happens in their brains when they agree to obey orders that cause pain to others”.

And by understanding the mechanisms of obedience that occur at the neurological level, we track down clues that can help prevent destructive obedience.

In "Just Following Orders!?" Emily Caspar thoroughly presents her research into the neural roots of our command-following behavior.

In a series of experiments beginning in 2016, the authors found that submissive people showed decreased activity in brain regions and circuits responsible for agency—responsibility, empathy, and guilt.

The validity of each research result is secured through careful analysis of various hypotheses and related data.

Consequently, the author's research aligns with existing neuroscience research on each brain region, providing a clearer understanding of already-discovered human characteristics and clearly explaining the various scientific mechanisms underlying human behavior, such as following and obeying orders.

Explaining the phenomenon of collective violence

Personal neuroscientific data

“It is a bad leader who orders us to kill people and become animals even though we are not animals.

that's right.

“It wasn’t us who caused this, it was the leaders.”

"Just Following Orders!?" is not a book that simply lists research results.

The neural processes that occur in individuals when obeying orders are expanded into a broader understanding of social phenomena through analysis and integration of existing social and psychological research.

In other words, the author's research is like a patchwork to grasp the whole picture of the incomprehensible event of genocide.

For example, interviews with perpetrators in Rwanda and Cambodia, where genocides occurred, are very impressive.

Their statements that they obeyed the command of courtesy, each confessing in a different way, show with surprising clarity how the neural workings of the brain, as revealed by the experimental results, can be realized.

Furthermore, the experimental results showing that both those who give orders and those who receive orders feel a low level of responsibility are consistent with previous studies on diffusion of responsibility and explain the phenomenon of group violence easily occurring in hierarchical structures such as the military.

The research commentary on empathy is also worth noting.

The decrease in brain activity associated with empathy when given commands, combined with evolutionary theories suggesting that humans show differential empathy toward outgroups and ingroups, and research in social psychology on categorization and dehumanization, allows us to paint a more holistic picture of collective violence.

The authors' experimental intention to identify the mechanisms of obedience at the neurological level already presupposes consideration of social intervention.

If we could identify 'how' the atrocities of submission occur, society could prevent them.

Each experimental result provides hints about the subjective will to refuse a command.

Additionally, the book introduces people in real history who refused immoral orders and tried to help others.

In the stories of Felicien Bahige and Jura Karuhimbi, who actively participated in rescue operations during the Rwandan genocide, readers can see the true nature of those who chose justice at the risk of sacrifice.

We are all 'monsters'

A Scientific Answer to the 'Banity of Evil'

“The devil is that they were not devils.”

Jewish philosopher Hannah Arendt proposed the concept of the banality of evil after observing war criminal Adolf Eichmann repeatedly claim at his trial in Jerusalem in 1961 that he was merely following orders, that he was “just a small cog in the machine” of Germany.

Eichmann, who led the massacre of millions of Jews, was not a 'monster' or a 'devil', but merely an incompetent human being who could not think as an ethical subject.

The concept of the banality of evil was once misunderstood as offering absolution to Eichmann and other war criminals, but it is now seen as a warning that anyone can easily become evil in a totalitarian system.

In the book, the author confesses to the special difficulties he encountered while studying the neurological changes that occur in those who resist orders.

To observe the brains of disobedient people, there had to be someone who did not follow coercive orders.

However, the non-compliance rate was so low that the experimental design had to be continually revised.

The reduced sense of responsibility, empathy, and guilt that occurs in the brain when we obey commands makes Emily Caspar's research feel like a scientific answer to the banality of evil.

As Hannah Arendt would have it, the banality of obedience is not a hopeless diagnosis for humanity.

Humans, who have developed civilization by forming groups over a long period of time, have naturally evolved to follow their in-group and reject out-groups.

The author, who has examined neuroscientific findings on obedience, also cautions against assuming that those who submit to unjust orders are "evil" or "monsters."

This is because such emotional categorization can “overlook the broader historical, economic, political, and social context in which the events occurred.”

Rather, it emphasizes that the most urgent task is to “develop interventions that promote empathy, moral courage, and independent thinking” through a “sensitive interdisciplinary approach” and to break the vicious cycle of violence.

This is a story that has great implications for our country, which still lives in an era of command and obedience.

Why did they obey orders?

Cognitive neuroscience research on humans engaging in collective violence

“Historically, the most terrible things—wars, genocide, slavery—have not happened because of disobedience, but because of obedience.”

“I was just following orders.” This is a statement of evasion of responsibility that can be heard from all participants, including those responsible, when a state-sponsored violence or massacre occurs.

This is also the defense presented by the majority of the 24 leaders indicted at the First International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg, which held them accountable for war crimes during World War II.

Of course, their excuses were not taken into account, and all but three were found guilty, with twelve of the defendants sentenced to death.

Nevertheless, how to punish the enlisted men and non-commissioned officers who carried out brutal acts under orders at the lowest level of the command chain became a subject of debate.

Do those who follow orders under duress temporarily lose their free will? Even so, are such brutal acts perpetrated simply because they're ordered to do so?

"Just Following Orders!?: The Obedient Brain, the Resisting Brain" is written by Emily A., Associate Professor of Experimental Psychology at Ghent University in Belgium.

This book is a compilation of Caspar's research, which he has been conducting since 2016, and reveals the cognitive neuroscientific processes that occur in the human brain when obeying commands.

The book also analyzes extensive social, psychological, and cognitive neuroscience data to provide comprehensive knowledge on the causes of genocide and mass violence.

What is special is that it does not remain within a limited research framework.

The author acknowledges the limitations of laboratory research, which is limited to controlled environments and small populations, and synthesizes the experimental results after visiting Rwanda and Cambodia, where genocides occurred, and interviewing actual perpetrators of the massacres.

Moreover, based on this information, we are exploring ways to prevent our society from becoming tainted by collective violence.

Emily Caspar, a neuropsychologist and cognitive neuroscience major, has studied how obedience to authority and commands affects individual behavior.

The uniqueness of the Caspar study lies in the objective observation of changes in the subject that occur during the command and execution process at the level of cognitive neuroscience.

While previous psychological research has focused on demonstrating the brutality with which humans can obey orders, his research illuminates the changes in the brains of those who follow orders and their implications.

His doctoral thesis, "Coercion Changes the Human Brain's Subjective Consciousness," caused a sensation with its neuroscientific approach and immediately captured the attention of the psychology and scientific communities.

For this paper, Caspar won the 2016 Royal Belgian Academy Prize in Psychology, which is awarded every three years for the best psychology doctoral dissertation, and in the same year, he won both the William James Prize and the Evens Prize in Science from the Society for the Scientific Study of Consciousness, which are awarded for related research.

A series of studies on the same topic followed, leading to his being nominated for the Rising Star Award of the International Psychological Association in 2017 and winning the Early Career Award of the International Society of Social Neuroscience in 2023.

Both of these awards are for early-career researchers with little research experience, and they are a testament to the significant attention Caspar is receiving.

What happens in a submissive brain?

Finding the Neural Roots of Command-Following Behavior

“More than that, I wanted to understand what happens in people’s brains when they agree to obey orders that cause pain to others.”

Emily Caspar explains that her research was designed under the influence of the Milgram experiment.

The 'Obedience to Authority' study conducted by psychologist Stanley Milgram in 1961 was an experiment to see how much pain participants could inflict on others when given orders by the experimenter.

The experiment was shocking, with 65 percent of participants applying the maximum voltage of 450 volts on command, "despite the screams and pleas" of the other person.

This experiment became the most important reference in obedience research, and subsequent similar experiments by other researchers confirmed that the results of the Milgram experiment were repeated.

The Milgram experiment and other similar experiments have all shown that humans can inflict significant harm on other humans simply by following orders, without any specific motivation.

However, Emily Caspar points out that the Milgram experiment and similar experiments “only tell us whether or not individuals will obey orders from authority figures in a given situation.”

Previous research has shown that “we cannot understand how people can commit atrocities when they are following orders.”

Starting with 'how', the author devises an experiment that combines cognitive neuroscience with the Milgram study.

That is, “what happens in their brains when they agree to obey orders that cause pain to others”.

And by understanding the mechanisms of obedience that occur at the neurological level, we track down clues that can help prevent destructive obedience.

In "Just Following Orders!?" Emily Caspar thoroughly presents her research into the neural roots of our command-following behavior.

In a series of experiments beginning in 2016, the authors found that submissive people showed decreased activity in brain regions and circuits responsible for agency—responsibility, empathy, and guilt.

The validity of each research result is secured through careful analysis of various hypotheses and related data.

Consequently, the author's research aligns with existing neuroscience research on each brain region, providing a clearer understanding of already-discovered human characteristics and clearly explaining the various scientific mechanisms underlying human behavior, such as following and obeying orders.

Explaining the phenomenon of collective violence

Personal neuroscientific data

“It is a bad leader who orders us to kill people and become animals even though we are not animals.

that's right.

“It wasn’t us who caused this, it was the leaders.”

"Just Following Orders!?" is not a book that simply lists research results.

The neural processes that occur in individuals when obeying orders are expanded into a broader understanding of social phenomena through analysis and integration of existing social and psychological research.

In other words, the author's research is like a patchwork to grasp the whole picture of the incomprehensible event of genocide.

For example, interviews with perpetrators in Rwanda and Cambodia, where genocides occurred, are very impressive.

Their statements that they obeyed the command of courtesy, each confessing in a different way, show with surprising clarity how the neural workings of the brain, as revealed by the experimental results, can be realized.

Furthermore, the experimental results showing that both those who give orders and those who receive orders feel a low level of responsibility are consistent with previous studies on diffusion of responsibility and explain the phenomenon of group violence easily occurring in hierarchical structures such as the military.

The research commentary on empathy is also worth noting.

The decrease in brain activity associated with empathy when given commands, combined with evolutionary theories suggesting that humans show differential empathy toward outgroups and ingroups, and research in social psychology on categorization and dehumanization, allows us to paint a more holistic picture of collective violence.

The authors' experimental intention to identify the mechanisms of obedience at the neurological level already presupposes consideration of social intervention.

If we could identify 'how' the atrocities of submission occur, society could prevent them.

Each experimental result provides hints about the subjective will to refuse a command.

Additionally, the book introduces people in real history who refused immoral orders and tried to help others.

In the stories of Felicien Bahige and Jura Karuhimbi, who actively participated in rescue operations during the Rwandan genocide, readers can see the true nature of those who chose justice at the risk of sacrifice.

We are all 'monsters'

A Scientific Answer to the 'Banity of Evil'

“The devil is that they were not devils.”

Jewish philosopher Hannah Arendt proposed the concept of the banality of evil after observing war criminal Adolf Eichmann repeatedly claim at his trial in Jerusalem in 1961 that he was merely following orders, that he was “just a small cog in the machine” of Germany.

Eichmann, who led the massacre of millions of Jews, was not a 'monster' or a 'devil', but merely an incompetent human being who could not think as an ethical subject.

The concept of the banality of evil was once misunderstood as offering absolution to Eichmann and other war criminals, but it is now seen as a warning that anyone can easily become evil in a totalitarian system.

In the book, the author confesses to the special difficulties he encountered while studying the neurological changes that occur in those who resist orders.

To observe the brains of disobedient people, there had to be someone who did not follow coercive orders.

However, the non-compliance rate was so low that the experimental design had to be continually revised.

The reduced sense of responsibility, empathy, and guilt that occurs in the brain when we obey commands makes Emily Caspar's research feel like a scientific answer to the banality of evil.

As Hannah Arendt would have it, the banality of obedience is not a hopeless diagnosis for humanity.

Humans, who have developed civilization by forming groups over a long period of time, have naturally evolved to follow their in-group and reject out-groups.

The author, who has examined neuroscientific findings on obedience, also cautions against assuming that those who submit to unjust orders are "evil" or "monsters."

This is because such emotional categorization can “overlook the broader historical, economic, political, and social context in which the events occurred.”

Rather, it emphasizes that the most urgent task is to “develop interventions that promote empathy, moral courage, and independent thinking” through a “sensitive interdisciplinary approach” and to break the vicious cycle of violence.

This is a story that has great implications for our country, which still lives in an era of command and obedience.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: January 24, 2025

- Page count, weight, size: 380 pages | 508g | 145*210*22mm

- ISBN13: 9788962626421

- ISBN10: 896262642X

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)