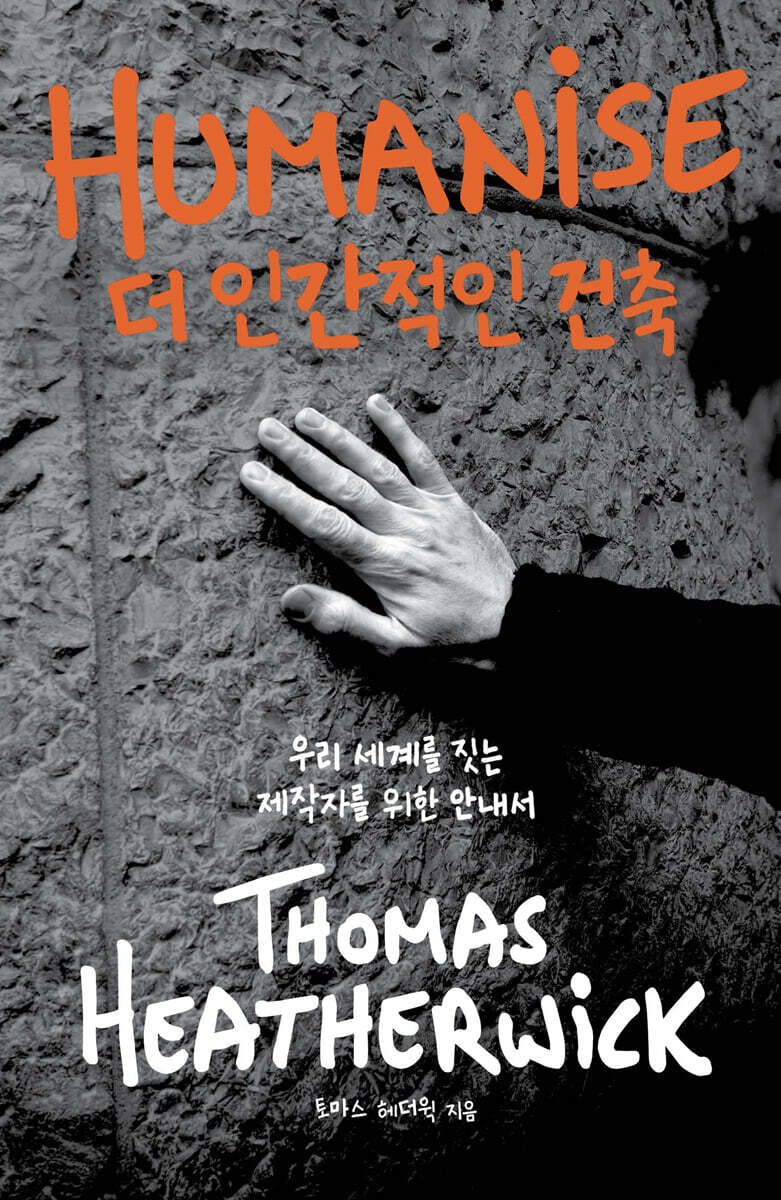

More human architecture

|

Description

Book Introduction

- A word from MD

-

No more boring city architectureAlthough each country has a different history and culture, the landscapes of cities around the world are similar.

Tall buildings built with straight lines and squares, similar color tones, and space design that is more friendly to cars than pedestrians.

World-renowned designer Thomas Heatherwick says we should stop building boring architecture.

It is time to restore publicness and enjoyment to urban spaces.

December 3, 2024. Humanities PD Son Min-gyu

“A book that will help us see the world we live in with different eyes!”

Tony Fadell (former Apple chief designer), Alain de Botton (writer),

Recommended by Terry Farrell (Incheon International Airport designer), Lee Mi-kyung (CJ Vice President), Lee Jung-jae (actor), and others

World-renowned designer Thomas Heatherwick,

Talking about the future direction of architecture and cities

“Our world is losing its humanity.

Too many cities feel soulless and depressing.

Look around you.

“What do the buildings surrounding us look like?” 『A More Human Architecture』 is a story about humanity and architecture told through architecture by Thomas Heatherwick, one of the world’s most imaginative designers.

Based on various cases, it presents sharp opinions on how the buildings we live in and are with us affect us, and in particular, how linear and boring buildings devour people and the environment.

Through hundreds of images, Heatherwick offers a passionate analysis of why we are surrounded by buildings that make people sick, make us miserable, and destroy our planet, and how we can make cities better for everyone.

He also combines his 30 years of experience creating bold and beautiful buildings with neuroscience and cognitive psychology to tell a humanistic story about architecture.

Filled with hundreds of images of human and inhuman architectural structures, this book guides us on a journey toward "human architecture."

"A More Human Architecture" is a book that will inspire humanity to rebuild a world that is not boring.

Tony Fadell (former Apple chief designer), Alain de Botton (writer),

Recommended by Terry Farrell (Incheon International Airport designer), Lee Mi-kyung (CJ Vice President), Lee Jung-jae (actor), and others

World-renowned designer Thomas Heatherwick,

Talking about the future direction of architecture and cities

“Our world is losing its humanity.

Too many cities feel soulless and depressing.

Look around you.

“What do the buildings surrounding us look like?” 『A More Human Architecture』 is a story about humanity and architecture told through architecture by Thomas Heatherwick, one of the world’s most imaginative designers.

Based on various cases, it presents sharp opinions on how the buildings we live in and are with us affect us, and in particular, how linear and boring buildings devour people and the environment.

Through hundreds of images, Heatherwick offers a passionate analysis of why we are surrounded by buildings that make people sick, make us miserable, and destroy our planet, and how we can make cities better for everyone.

He also combines his 30 years of experience creating bold and beautiful buildings with neuroscience and cognitive psychology to tell a humanistic story about architecture.

Filled with hundreds of images of human and inhuman architectural structures, this book guides us on a journey toward "human architecture."

"A More Human Architecture" is a book that will inspire humanity to rebuild a world that is not boring.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Part 1: Human and Inhuman Places

human place

100-year disaster

The Anatomy of Boredom

Part 2: How the Cult of Boredom Came to Rule the World

What is an architect?

Meet the God of Boredom

How to Start a Cult (Accidentally)

Why does it always seem like profit?

Part 3: How to Humanize the World Again

Think differently

A problem that everyone is keeping quiet about

Move differently

(Expected) Frequently Asked Questions

To the pedestrian

Acknowledgements

source

Photo copyright

Join the humanization movement

human place

100-year disaster

The Anatomy of Boredom

Part 2: How the Cult of Boredom Came to Rule the World

What is an architect?

Meet the God of Boredom

How to Start a Cult (Accidentally)

Why does it always seem like profit?

Part 3: How to Humanize the World Again

Think differently

A problem that everyone is keeping quiet about

Move differently

(Expected) Frequently Asked Questions

To the pedestrian

Acknowledgements

source

Photo copyright

Join the humanization movement

Detailed image

Into the book

Casa Mila is a feast of stately curves.

Sixteen generations of windows stand out as if they were carved coolly into the limestone cliffs.

It's far from flat.

The facade of the nine-story building shimmers and dances wonderfully in the light.

Up and down, in and out, the building itself seems to breathe.

---- p.15

No matter who you are or where you come from, believing that you are special is fundamental to human nature.

We must believe in our own specialness.

Walden 7 was built as public housing for people of low socioeconomic status, and people who walk in and out of the building on a daily basis feel like superheroes.

It is not a building built with expensive materials at great expense for the wealthy.

However, a great deal of care and attention was put into the design, and that care and pride must have been a great strength to the people who have lived here for decades.

--- p.

40

In 2008, American scientists studied the effects of different types of buildings on older adults living in East Little Havana, a poor Hispanic neighborhood in Miami, Florida.

As a result, they found that residents of buildings lacking "positive entrance features," such as a front door or wide entry stairs, were nearly three times more likely to experience health problems.

Although some of these differences are thought to be related to the direct physical benefits of climbing front steps, equally important is the fact that those who do not have these para-social spaces in front of their homes are more likely to be socially isolated due to their weak ties to the community.

--- p.

121

Some architects consider themselves artists.

The problem is that the rest of us have no choice but to live with this 'art'.

It is impossible to avoid it, just as one cannot avoid boring movies, boring novels, or boring paintings.

Their 'art' becomes the place where we all live, work, shop, heal and teach.

Their 'art' becomes the boring streets we walk every day - streets that stress us, unhappiness and loneliness, that ruin our lives, weaken our communities and pollute our planet.

--- p.143

At the beginning of the 20th century, most urban areas around the world were dangerous, dirty, and sick.

Le Corbusier compared a typical family home to “an old carriage full of tuberculosis.”

The winding old streets of medieval city centers were so crowded that they were believed to have caused “physical and nervous diseases” and a decline in “hygienic and moral health.”

--- p.196

The bare concrete walls so beloved by Le Corbusier and other modernists turned out to be hostile to humanity precisely because they lacked such complexity.

We unconsciously experience materials as if we were touching them through a neural process called thermosensation.

We feel comfortable when we see warm materials like wood.

On the other hand, concrete, metal, and glass tend to feel cold and uncomfortable, triggering an instinct to retreat.

--- p.206

The brain processes locations as a series of instructions, seeking answers to the following questions:

How should I interact with this place? Where should I walk? Where should I sit? Where should I find shelter? Which direction should I go? Traditional streets are filled with answers to these questions.

It is a stage for successful action.

Not so with modernist squares or wide, empty avenues.

--- p.229

A close friend of mine once participated in a debate between two giants of the architectural world.

It was said that at a high-society gathering in London, the topic of discussion was how much public opinion mattered to a building.

My friend told me something amazing.

“The majority of people said that the public’s level of knowledge was not high enough to listen,” he added.

“Everyone was like this.

“Why would you ask the public? What do they know?” This culture has served as a means of protecting one’s ego when the public rejects the works of elite building designers.

The public has no discerning eye and cannot see the goodness of our work.

Even though we know, we know more.

--- p.260

Like Le Corbusier, who built Ronchamp, the medieval cathedral builders were geniuses at evoking powerful emotions through their buildings.

Upon entering the cathedral, one is immediately overwhelmed by the darkness, coolness, and the resonance of the surrounding stonework.

I look up at the grand arched ceiling, towards heaven, my voice still.

Your breathing slows down and you are enveloped in a meditative, calm feeling.

The building has a profound effect on the feeling.

The decisions of a designer who died centuries ago continue to shape us to this very moment.

They found that emotions are a very important function of the structure.

--- p.377

Likewise, Steve Jobs, the technologist and co-founder of Apple, intuitively understood that design could influence and move emotions.

When he first started his business, Jobs instinctively knew that the public viewed computers as overly complex, taboo, and impersonal.

His genius was to change the way people felt about electronics by making them more human.

--- p.379

We need to create a world where building designers approach things with a millennial mindset.

New buildings should be designed to weather and bend with the natural movements of the ground, and to be easily repaired and reused when worn and soiled.

--- p.383

Any critic who truly wants to improve the world should consider 99 percent of the buildings: the new tower blocks of provincial cities and the sprawling housing estates on the outskirts.

Not the 1 percent of special cities like Sydney, Berlin, New York, Cape Town, or Seoul.

As of now, I feel like I'm spending 99 percent of my time on this special 1 percent story.

(…) Above all, we need critics who are passionate about exploring the impact that buildings have on the emotions and lives of millions of passersby.

Sixteen generations of windows stand out as if they were carved coolly into the limestone cliffs.

It's far from flat.

The facade of the nine-story building shimmers and dances wonderfully in the light.

Up and down, in and out, the building itself seems to breathe.

---- p.15

No matter who you are or where you come from, believing that you are special is fundamental to human nature.

We must believe in our own specialness.

Walden 7 was built as public housing for people of low socioeconomic status, and people who walk in and out of the building on a daily basis feel like superheroes.

It is not a building built with expensive materials at great expense for the wealthy.

However, a great deal of care and attention was put into the design, and that care and pride must have been a great strength to the people who have lived here for decades.

--- p.

40

In 2008, American scientists studied the effects of different types of buildings on older adults living in East Little Havana, a poor Hispanic neighborhood in Miami, Florida.

As a result, they found that residents of buildings lacking "positive entrance features," such as a front door or wide entry stairs, were nearly three times more likely to experience health problems.

Although some of these differences are thought to be related to the direct physical benefits of climbing front steps, equally important is the fact that those who do not have these para-social spaces in front of their homes are more likely to be socially isolated due to their weak ties to the community.

--- p.

121

Some architects consider themselves artists.

The problem is that the rest of us have no choice but to live with this 'art'.

It is impossible to avoid it, just as one cannot avoid boring movies, boring novels, or boring paintings.

Their 'art' becomes the place where we all live, work, shop, heal and teach.

Their 'art' becomes the boring streets we walk every day - streets that stress us, unhappiness and loneliness, that ruin our lives, weaken our communities and pollute our planet.

--- p.143

At the beginning of the 20th century, most urban areas around the world were dangerous, dirty, and sick.

Le Corbusier compared a typical family home to “an old carriage full of tuberculosis.”

The winding old streets of medieval city centers were so crowded that they were believed to have caused “physical and nervous diseases” and a decline in “hygienic and moral health.”

--- p.196

The bare concrete walls so beloved by Le Corbusier and other modernists turned out to be hostile to humanity precisely because they lacked such complexity.

We unconsciously experience materials as if we were touching them through a neural process called thermosensation.

We feel comfortable when we see warm materials like wood.

On the other hand, concrete, metal, and glass tend to feel cold and uncomfortable, triggering an instinct to retreat.

--- p.206

The brain processes locations as a series of instructions, seeking answers to the following questions:

How should I interact with this place? Where should I walk? Where should I sit? Where should I find shelter? Which direction should I go? Traditional streets are filled with answers to these questions.

It is a stage for successful action.

Not so with modernist squares or wide, empty avenues.

--- p.229

A close friend of mine once participated in a debate between two giants of the architectural world.

It was said that at a high-society gathering in London, the topic of discussion was how much public opinion mattered to a building.

My friend told me something amazing.

“The majority of people said that the public’s level of knowledge was not high enough to listen,” he added.

“Everyone was like this.

“Why would you ask the public? What do they know?” This culture has served as a means of protecting one’s ego when the public rejects the works of elite building designers.

The public has no discerning eye and cannot see the goodness of our work.

Even though we know, we know more.

--- p.260

Like Le Corbusier, who built Ronchamp, the medieval cathedral builders were geniuses at evoking powerful emotions through their buildings.

Upon entering the cathedral, one is immediately overwhelmed by the darkness, coolness, and the resonance of the surrounding stonework.

I look up at the grand arched ceiling, towards heaven, my voice still.

Your breathing slows down and you are enveloped in a meditative, calm feeling.

The building has a profound effect on the feeling.

The decisions of a designer who died centuries ago continue to shape us to this very moment.

They found that emotions are a very important function of the structure.

--- p.377

Likewise, Steve Jobs, the technologist and co-founder of Apple, intuitively understood that design could influence and move emotions.

When he first started his business, Jobs instinctively knew that the public viewed computers as overly complex, taboo, and impersonal.

His genius was to change the way people felt about electronics by making them more human.

--- p.379

We need to create a world where building designers approach things with a millennial mindset.

New buildings should be designed to weather and bend with the natural movements of the ground, and to be easily repaired and reused when worn and soiled.

--- p.383

Any critic who truly wants to improve the world should consider 99 percent of the buildings: the new tower blocks of provincial cities and the sprawling housing estates on the outskirts.

Not the 1 percent of special cities like Sydney, Berlin, New York, Cape Town, or Seoul.

As of now, I feel like I'm spending 99 percent of my time on this special 1 percent story.

(…) Above all, we need critics who are passionate about exploring the impact that buildings have on the emotions and lives of millions of passersby.

--- p.459

Publisher's Review

“If you want to know who we are, look at our buildings.”

An architectural guide for those of us who live surrounded by linear, dull, and boring buildings.

"They say that simply walking through a dull landscape is stressful. What would happen if you had to live in a dull house for the rest of your life, this year and next? What would happen if you had to work your whole life in a dull office, a dull factory, a dull warehouse, a dull hospital, a dull school?" _Excerpt from the text

If you live in South Korea, you will notice that most of the buildings surrounding you have a similar shape.

The city center is full of factory-style apartments.

Most people commute from their straight apartment buildings to straight, horizontal office buildings.

What thoughts come to mind as you move between these buildings?

The author of this book, Thomas Heatherwick, draws on his experience of creating diverse, bold, human, and original things, from buildings to furniture, over the past 30 years to argue that the boring buildings around us are making people emotionally ill, further destroying the environment, and even causing war.

And he argues that the buildings that surround us must be humane.

The building is doing something so horrific? What on earth is happening to us?

Boring, inhumane architecture vs. generous, humane architecture

“From the beginning, the buildings we have created have looked and felt human.

But things changed in the 20th century.

A new architectural method, unprecedented in world history, has emerged.

Boring buildings began to be erected all over the world, including in Europe, the United States, South America, Asia, Africa, Australia, and the Soviet Union.

“And so, all of a sudden, at an unbelievable speed, boredom took over the world.” _From the text

Casa Mila, built by Spanish architect Gaudi, is a building that perfectly achieves repetition and complexity with its winding curves.

In "A More Human Architecture," Heatherwick says that such buildings are human buildings.

Because Casa Mila inspires, reaches out and brings a smile to the faces of those who pass by it every day.

Anyone can visit Casa Milà without paying a penny, and it delights the viewer and welcomes thousands of people every day with its generous humanity.

But for Heatherwick, modern buildings are inhumane.

(As you'll see in the book, this is not necessarily the case for all buildings.) As we all know, the facades of modern buildings surrounding cities tend to be incredibly flat.

It is a form where windows and doors can barely go in or out.

The roof is often flat.

It's too plain, too unadorned, too linear, too monotonous, too shiny.

The exteriors of modern buildings are often made of smooth, flat materials such as metal or glass.

(The increase in glass facades has also contributed to the mass slaughter of birds.

It is estimated that in the United States alone, between 100 million and 1 billion birds die each year from collisions with glass windows.) Also, modern buildings often take the form of rectangles made up of small rectangles.

When these grid-like buildings are lined up in a straight line, the landscape becomes a repetitive matrix of flat rectangles.

Heatherwick argues that this kind of monotony is neither inspiring, exciting, nor captivating; it is simply anonymous.

A hundred years or more ago, the exterior of a building conveyed the character of the place, but today's buildings say nothing.

When excessive boredom takes hold in a space, boredom becomes harmful to humans.

So what effect do boring buildings have on us?

The impact of distance and buildings: an analysis based on neuroscience and cognitive psychology.

In 『A More Human Architecture』, there are various reasons to support the author Heatherwick's argument that boredom is harmful to humans.

For example, neuroscientist Colin Ellard analyzed how boring buildings affect humans.

“In front of the empty facade, that is, the front of the building, people were quiet, cowering, and passive.

In more lively settings, people were more energetic and chatty, and had a harder time calming down.” A review of the data collected revealed that people had higher stress levels in dull places.

According to a British scientific study, “people who feel bored are more likely to die earlier than those who are not bored.”

Also, at Robert Taylor Homes, a Chicago housing project studied by Dr. Francis Kuo of the University of Illinois' Institute of Landscape Architecture and Human Health, those who faced a green courtyard with grass, shrubs, and trees experienced less stress, greater concentration, and better coping with life's challenges, while those who faced a plain, gray courtyard had the opposite effect.

Why boring buildings harm the environment and contribute to division and war.

When you hear the word 'boring', you probably think this.

"A book about the boredom of buildings... Is that really true? At a time like this, when the world is plagued by countless problems—social injustice, the climate crisis, political polarization, war, dictatorship, corruption—the subject of this much-maligned, raucous Busan... What, a boring building?!?" And then you might think,

"Who are you to find buildings boring? Just because you don't like them doesn't mean this shopping center or that office complex is bad." It's valid.

I wouldn't blame you if you were thinking the same thing.

I would have been like that too.

All I can do is ask you to just wait a few pages.

_From the text

Heatherwick says:

The reason why boring buildings are harmful to the environment is that they are not loved by passersby and are often demolished because they become shabby and neglected.

In other words, boring buildings are not sustainable.

The editor of Architects' Journal called demolition "architecture's dirty secret."

In the United States, approximately 1 billion square feet of buildings are demolished and rebuilt every 12 months.

That's like half of Washington, D.C. being torn down and rebuilt every year.

In the UK, 50,000 buildings are demolished every year, generating 126 million tonnes of waste, and the average lifespan of a commercial building is around 40 years.

Surprisingly, the construction industry accounts for almost two-thirds of all waste generated across the UK.

In China, the construction industry generated 3.2 billion tons of waste in 2021, most of which came from demolition.

By 2026, this figure is expected to exceed 4 billion tonnes.

Building a building is bad for the environment, and tearing it down and building a new one in its place is even worse for the environment.

Additionally, boring buildings promote a number of negative behaviors, contributing to division and war.

Scientific American reported that boredom increases the risk of “depression, anxiety, drug addiction, alcoholism, compulsive gambling, eating disorders, hostility, anger, social decline, poor grades, and poor job performance.”

Researchers at King's College London found that boredom "leads people to take greater risks in areas such as finances, ethics, leisure, health and safety," and the scientists also found that excessive boredom increases the likelihood of adopting extreme political beliefs.

Human beings have the right to live in a humane place.

How to Humanize the World Again

Empire State Building, Notre Dame Cathedral, Taj Mahal, The Shard, Gardens by the Bay, Burj Khalifa, Hallgrímskirkja, Eiffel Tower, Louvre Museum, Sagrada Familia…

These buildings are the world's most loved, as ranked by popular Google searches.

Except for Notre Dame Cathedral, the Taj Mahal, and the Eiffel Tower, all of these buildings were built in the last 100 years.

These buildings are human.

So how can we humanize the buildings of this world? Heatherwick suggests the answer lies in the "humanization principle."

First, ACCEPT: Recognize that how users feel is central to the function of the building.

Second, BUILDINGS: Design buildings with the hope and expectation that they will easily last a thousand years.

Third, CONCENTRATE: Concentrate the building's interesting features within two meters of the doorway.

These are principles that the creators who build our world should look to in the future.

Apple co-founder Steve Jobs also intuitively understood that design influences emotions.

The primary audience for building designers and architects is the public.

Heatherwick says:

The public is never wrong.

An architectural guide for those of us who live surrounded by linear, dull, and boring buildings.

"They say that simply walking through a dull landscape is stressful. What would happen if you had to live in a dull house for the rest of your life, this year and next? What would happen if you had to work your whole life in a dull office, a dull factory, a dull warehouse, a dull hospital, a dull school?" _Excerpt from the text

If you live in South Korea, you will notice that most of the buildings surrounding you have a similar shape.

The city center is full of factory-style apartments.

Most people commute from their straight apartment buildings to straight, horizontal office buildings.

What thoughts come to mind as you move between these buildings?

The author of this book, Thomas Heatherwick, draws on his experience of creating diverse, bold, human, and original things, from buildings to furniture, over the past 30 years to argue that the boring buildings around us are making people emotionally ill, further destroying the environment, and even causing war.

And he argues that the buildings that surround us must be humane.

The building is doing something so horrific? What on earth is happening to us?

Boring, inhumane architecture vs. generous, humane architecture

“From the beginning, the buildings we have created have looked and felt human.

But things changed in the 20th century.

A new architectural method, unprecedented in world history, has emerged.

Boring buildings began to be erected all over the world, including in Europe, the United States, South America, Asia, Africa, Australia, and the Soviet Union.

“And so, all of a sudden, at an unbelievable speed, boredom took over the world.” _From the text

Casa Mila, built by Spanish architect Gaudi, is a building that perfectly achieves repetition and complexity with its winding curves.

In "A More Human Architecture," Heatherwick says that such buildings are human buildings.

Because Casa Mila inspires, reaches out and brings a smile to the faces of those who pass by it every day.

Anyone can visit Casa Milà without paying a penny, and it delights the viewer and welcomes thousands of people every day with its generous humanity.

But for Heatherwick, modern buildings are inhumane.

(As you'll see in the book, this is not necessarily the case for all buildings.) As we all know, the facades of modern buildings surrounding cities tend to be incredibly flat.

It is a form where windows and doors can barely go in or out.

The roof is often flat.

It's too plain, too unadorned, too linear, too monotonous, too shiny.

The exteriors of modern buildings are often made of smooth, flat materials such as metal or glass.

(The increase in glass facades has also contributed to the mass slaughter of birds.

It is estimated that in the United States alone, between 100 million and 1 billion birds die each year from collisions with glass windows.) Also, modern buildings often take the form of rectangles made up of small rectangles.

When these grid-like buildings are lined up in a straight line, the landscape becomes a repetitive matrix of flat rectangles.

Heatherwick argues that this kind of monotony is neither inspiring, exciting, nor captivating; it is simply anonymous.

A hundred years or more ago, the exterior of a building conveyed the character of the place, but today's buildings say nothing.

When excessive boredom takes hold in a space, boredom becomes harmful to humans.

So what effect do boring buildings have on us?

The impact of distance and buildings: an analysis based on neuroscience and cognitive psychology.

In 『A More Human Architecture』, there are various reasons to support the author Heatherwick's argument that boredom is harmful to humans.

For example, neuroscientist Colin Ellard analyzed how boring buildings affect humans.

“In front of the empty facade, that is, the front of the building, people were quiet, cowering, and passive.

In more lively settings, people were more energetic and chatty, and had a harder time calming down.” A review of the data collected revealed that people had higher stress levels in dull places.

According to a British scientific study, “people who feel bored are more likely to die earlier than those who are not bored.”

Also, at Robert Taylor Homes, a Chicago housing project studied by Dr. Francis Kuo of the University of Illinois' Institute of Landscape Architecture and Human Health, those who faced a green courtyard with grass, shrubs, and trees experienced less stress, greater concentration, and better coping with life's challenges, while those who faced a plain, gray courtyard had the opposite effect.

Why boring buildings harm the environment and contribute to division and war.

When you hear the word 'boring', you probably think this.

"A book about the boredom of buildings... Is that really true? At a time like this, when the world is plagued by countless problems—social injustice, the climate crisis, political polarization, war, dictatorship, corruption—the subject of this much-maligned, raucous Busan... What, a boring building?!?" And then you might think,

"Who are you to find buildings boring? Just because you don't like them doesn't mean this shopping center or that office complex is bad." It's valid.

I wouldn't blame you if you were thinking the same thing.

I would have been like that too.

All I can do is ask you to just wait a few pages.

_From the text

Heatherwick says:

The reason why boring buildings are harmful to the environment is that they are not loved by passersby and are often demolished because they become shabby and neglected.

In other words, boring buildings are not sustainable.

The editor of Architects' Journal called demolition "architecture's dirty secret."

In the United States, approximately 1 billion square feet of buildings are demolished and rebuilt every 12 months.

That's like half of Washington, D.C. being torn down and rebuilt every year.

In the UK, 50,000 buildings are demolished every year, generating 126 million tonnes of waste, and the average lifespan of a commercial building is around 40 years.

Surprisingly, the construction industry accounts for almost two-thirds of all waste generated across the UK.

In China, the construction industry generated 3.2 billion tons of waste in 2021, most of which came from demolition.

By 2026, this figure is expected to exceed 4 billion tonnes.

Building a building is bad for the environment, and tearing it down and building a new one in its place is even worse for the environment.

Additionally, boring buildings promote a number of negative behaviors, contributing to division and war.

Scientific American reported that boredom increases the risk of “depression, anxiety, drug addiction, alcoholism, compulsive gambling, eating disorders, hostility, anger, social decline, poor grades, and poor job performance.”

Researchers at King's College London found that boredom "leads people to take greater risks in areas such as finances, ethics, leisure, health and safety," and the scientists also found that excessive boredom increases the likelihood of adopting extreme political beliefs.

Human beings have the right to live in a humane place.

How to Humanize the World Again

Empire State Building, Notre Dame Cathedral, Taj Mahal, The Shard, Gardens by the Bay, Burj Khalifa, Hallgrímskirkja, Eiffel Tower, Louvre Museum, Sagrada Familia…

These buildings are the world's most loved, as ranked by popular Google searches.

Except for Notre Dame Cathedral, the Taj Mahal, and the Eiffel Tower, all of these buildings were built in the last 100 years.

These buildings are human.

So how can we humanize the buildings of this world? Heatherwick suggests the answer lies in the "humanization principle."

First, ACCEPT: Recognize that how users feel is central to the function of the building.

Second, BUILDINGS: Design buildings with the hope and expectation that they will easily last a thousand years.

Third, CONCENTRATE: Concentrate the building's interesting features within two meters of the doorway.

These are principles that the creators who build our world should look to in the future.

Apple co-founder Steve Jobs also intuitively understood that design influences emotions.

The primary audience for building designers and architects is the public.

Heatherwick says:

The public is never wrong.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: November 20, 2024

- Page count, weight, size: 496 pages | 688g | 129*198*40mm

- ISBN13: 9788925574868

- ISBN10: 8925574861

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)